‘No to Silence': Javier Valdez's Murder Highlights Persistent Perils for Mexican Journalists

Photo by Héctor Vivas (@hectorvivas) for Derecho Informar (@DerechoInformar). Used with permission.

The award-winning Sinaloa journalist and writer, Javier Valdez Cárdenas, was shot to death on Monday, May 15, on a street in Culiacán, a city in northwest Mexico, in broad daylight. Valdez was the editor and reporter of the local media outlet Ríodoce and was considered one of the top experts on drug trafficking in Mexico.

He was the sixth journalist murdered so far this year. On the same day, a little later, the reporter Jonathan Rodríguez of the weekly El Costeño died in an attack, in which his mother was also injured.

Valdez specialized in reporting on issues related to the government’s “war” against drug cartels, as well as political corruption usually involving Mexican governors. His relentless focus was on the relatives, the displaced, the orphans, the widows. He cared about names, not numbers. This is how he explained why he did what he did in a speech at the book fair in Los Angeles, California in 2015:

Seguimos con un déficit de genitales en el país, hay un déficit de genitales, al país le falta ciudadanía, le falta recuperar la calle, la dignidad y creo eso es hasta tarea de los periodistas, tenemos que dejar atrás el periodismo cuenta-muertos, el ‘ejecutómetro’, y contar historias de vida en medio de la muerte, historias de estoicidad, de lucha.

Muchos podemos morir, y muchos han muerto, y no están dentro del negocio (del narco), y no han estado dentro del negocio, y no son víctimas colaterales, ni son números, son personas.

We continue to lack genitals in this country. There is a lack of genitals, there is a lack of citizenship. We need to recover the streets, dignity, and I think that’s up to journalists. We need to leave behind the kind of journalism that counts deaths, the ‘execution-meter’, and [instead] tell stories of life in the midst of death, stories of stoicism, of struggle.

Many of us can die, and many have died, who were not in the business (of drug trafficking)… [they] were not collateral victims, nor numbers, they were people.

“They are killed for having made the grave mistake of living in Mexico, and being journalists”. Words of Javier Valdez #ADayWithoutJournalism  . Pictoline illustration. Used with permission.

. Pictoline illustration. Used with permission.

Image: Have you seen them? Journalists are increasingly disappearing.

Being tortured.

Being assassinated in Mexico.We can think that it’s only the messengers of the cartels that give the execution order. But no. It’s not just the cartels that kill journalists.

Politicians also do their extermination homework. Police. Colluding agents.

State prosecutors. Government officials. Soldiers.

They kill them for the sin of denouncing their mismanagement.

“They are killed for having made the grave mistake of living in Mexico, and being journalists.”

Valdéz always knew that exercising his profession in Mexico put his life at risk, as do many of his colleagues. In fact, as early as 2009, a grenade exploded outside the doors of Ríodoce. On that occasion, there was only physical damage to the building and the reasons behind the attack was never clarified. However, his desire to inform and give a voice to those who were silenced by violence always helped him overcome his apprehensions.

In his column, Malayerba, for Ríodoce, he once wrote the following lines under the title “They are going to kill you”:

Pero él tenía en el pericardio un chaleco antibalas. La luna en su mirada parecía un farol que aluzaba incluso de día. La pluma y la libreta eran rutas de escape, terapia, crucifixión y exorcismo. Escribía y escribía en la hoja en blanco y en la pantalla y salía espuma de sus dedos, de su boca, salpicándolo todo. Llanto y rabia y dolor y tristeza y coraje y consternación y furia en esos textos en los que hablaba del gobernador pisando mierda, del alcalde de billetes rebosando, del diputado que sonreía y parecía una caja registradora recibiendo y recibiendo fajos y haciendo tin en cada ingreso millonario.

But he had a bulletproof vest on. The moon in his gaze resembled a lantern that lit up even during the day. The pen and notebook were routes of escape, therapy, crucifixion and exorcism. He wrote and wrote on the blank sheet and on the screen, and foam came out from his fingers, his mouth, touching everything. Weeping and rage and pain and sadness and anger and dismay and fury in those texts in which he spoke of the governor stepping on shit, of the mayor of bills overflowing, of the representative who smiled and looked like a cash register receiving wads of cash and making a “chi-ching” sound with every millionaire's deposit.

In 2011, Javier Valdéz received the International Press Freedom Award granted by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). His speech (beginning at 5:13), re-emphasized the dangers faced by journalists in Mexico:

‘No to silence’

Reporters, activists, and readers shared their grief over the loss of such a committed voice, many of them recalling Valdez’s own words:

Tears in my eyes, hearing of the murder of Javier Valdez Cardenas in Culiacan, one of the best writers and journalists of Mexico. TRAGEDY.

— Ioan Grillo (@ioangrillo) May 15, 2017

… every time I visited Sinaloa, I would have drinks with him. Javier was a wonderful guy. His loss is devastating to all of us.

— Jan-Albert Hootsen (@jahootsen) May 15, 2017

“El buen periodismo, valiente, honesto, no tiene sociedad; está solo”: Javier Valdez. Lo mataron https://t.co/dnG98isu1Wpic.twitter.com/mXNU1IKrzT

— Sin Embargo MX (@SinEmbargoMX) May 15, 2017

“Good journalism, brave, dignified, responsible, honest, doesn't have society; it's alone”: Javier Valdez. They killed him.

[In the image, Valdez's quote in full]: “Good journalism, brave, dignified, responsible, honest, doesn’t have a society; it is alone, and that also speaks of our fragility, because it means that if they go against us or those journalists and they hurt them, nothing will happen.” – Javier Valdez

La dedicatoria de su último libro.

NARCOPERIODISMO de Javier Valdez.

— Risco (@jrisco) May 15, 2017

The dedication of his last book.

NARCOPERIODISMO by Javier Valdez.

Image: To Maicol O’Connor (+) and Tracy Wilkinson, immeasurable journalists, whom I both miss and love.

To the Mexican journalists brave and worthy, exiled, hidden, disappeared, assassinated, beaten, frightened and giving birth to stories, despite censorship and dark canons.

To Tania, Saríah, Fran, Javier Erasmo and Gris. For being with me, supporting me and sowing in me, in spite of clouds. Or maybe that’s why.

A recently created website, El Mañanero Diario, gave an account of the demonstrations that took place to condemn the homicide of Valdez:

Periodistas de todo el país se manifestaron en protesta por el asesinato del periodista sinaloense Javier Valdez. Sinaloa, Ciudad de México, Guerrero, Baja California y Jalisco fueron algunos de los estados en los que los profesionales de la información salieron a las calles para condenar el asesinato de Valdez y exigir mayor seguridad y un alto a la violencia contra el gremio.

En el Ángel de la Independencia [en la capital mexicana], se reunió un grupo de fotoperiodistas quienes, sobre la glorieta, con gis blanco, escribieron: “En México nos están matando” y “No al silencio”, con palabras formadas por los retratos de reporteros asesinados, como Gregorio Jiménez y Miroslava Breach.

Journalists across the country demonstrated in protest at the murder of Sinaloa journalist Javier Valdez. Sinaloa, Mexico City, Guerrero, Baja California, and Jalisco were some of the states in which news professionals took to the streets to condemn the murder of Valdez and to demand greater security and a stop to violence against the profession.

A group of photojournalists met At the Angel of Independence [in the Mexican capital], along the roundabout, who with white chalk wrote: “In Mexico they are killing us” and “No to silence,” with words formed by portraits of murdered reporters such as Gregorio Jiménez and Miroslava Breach.

“In Mexico, they are killing us. No to silence.” Photo by Héctor Vivas (@hectorvivas) for Derecho Informar (@DerechoInformar). Used with permission.

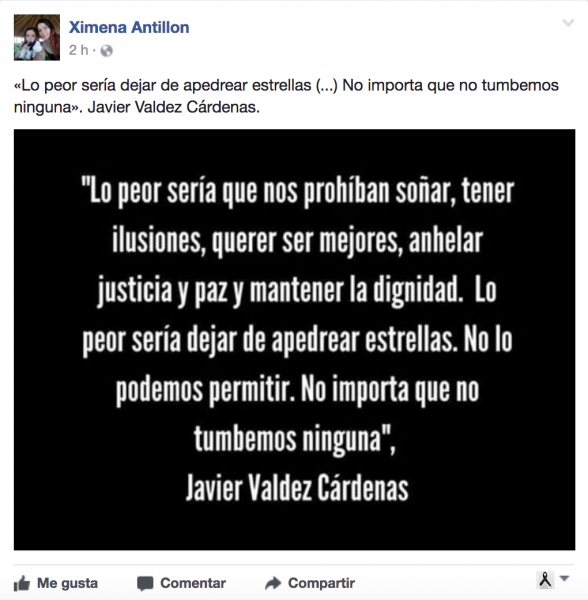

Screenshot of the public post of Ximena Antillón.

Image: “The worst thing would be forbidding us to dream, to have illusions; to want to be better, to long for justice and peace, and maintain dignity. The worst thing would be to stop stoning stars. We can’t allow it. It doesn’t matter if we don’t knock any down.” – Javier Valdez Cárdenas

No bastan sus condolencias por el asesinato de Javier Valdez Sr PeñaNieto. Pare ya está masacre o váyase! pic.twitter.com/5MNdxOX0RK

— epigmenio ibarra (@epigmenioibarra) May 15, 2017

Your condolences for the murder of Javier Valdéz are not enough Mr. Peña Nieto. Stop this slaughter now or leave!

Image:

@GobMx condemns the murder of journalist Javier Valdez. My condolences to his family and friends.

A district attorney that doesn't work

The Mexican State has an office dedicated exclusively — in theory — to seeking justice in crimes committed against those who practice journalism or comment on the right to information or freedom of press and expression.

The official name of the office is the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against the Freedom of Expression (FEADLE) and operates under the Attorney General of Mexico (PGR).

FEADLE, however, is one more branch of the abstruse bureaucratic framework of the country, which absorbs countless public resources while delivering nothing in return.

Suffice it to say that in relation to the cases of homicides committed against journalists so far this year, not a single person has been arrested.

The Mexican independent website, Animal Político reported:

En algo más de seis años -de julio de 2010 al 31 de diciembre de 2016- se registraron 798 denuncias por agresiones contra periodistas.

Pues bien, de esas 798 denuncias, de las cuales 47 fueron por asesinato, la FEADLE informó en respuesta a una solicitud de transparencia que solo tiene registro de tres sentencias condenatorias: una, en el año 2012; y otras dos en 2016. O en otras cifras: el 99.7% de las agresiones no ha recibido una sentencia.

In just over six years – from July 2010 to December 31, 2016 – there were 798 reports of attacks on journalists.

Well, out of these 798 complaints, of which 47 were for murder, FEADLE reported in response to a request for transparency that it only has three convictions registered: one in 2012; and another two in 2016. Or in other words 99.7% of attacks have not led to a criminal conviction.

The recorded reasons for the closure of the investigations by the attorney general include “incompetence” and “non-prosecution.” These technical and legal terms invariably mean the referral of the file to another authority, and ultimately, the termination of the investigation before a formal accusation has been made in the presence of a judge.

The result is impunity for offenders and the denial of justice for victims.

The website Sin Embargo noted:

En 2010, mediante acuerdo, se creó la FEADLE en las entrañas de la PGR y con el antecedente de otro órgano, la Fiscalía Especial para la Atención de Delitos cometidos contra Periodistas (FEADP). Los delitos en contra de los periodistas se incrementaron sin que se supera de un solo proceso [juicio] que concluyera en sentencia penal.

Ése es el organismo al que el Jefe del Ejecutivo [el Presidente de México] le ha pedido que apoye en Sinaloa para esclarecer el asesinato de Valdez Cárdenas, un periodista que se distinguió por un conocimiento profundo de la región norte donde han operado grupos de narcotraficantes desde los años treinta del siglo pasado.

In 2010, by agreement, FEADLE was created within the purview of the PGR and against the background of another government body, the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes Committed against Journalists (FEADP). Crimes against journalists increased without […] a single process [trial] that concluded in a penal sentence.

This is the government body that the Chief Executive [the President of Mexico] has asked to support in Sinaloa in order to clarify the murder of Valdez Cárdenas, a journalist who reputed for his profound knowledge of the northern region where groups of drug traffickers have operated since the 1930s.

In spite of all these antecedents, in the days after the murder of Valdez, the Mexican State announced a set of measures to protect journalists; the main one being an enlargement of FEADLE's personnel.

The passivity or inefficiency with which the Mexican state responds to violence against journalist has offered a perverse incentive to all those interested in silencing voices to continue resorting to violence, driving threatened voices towards self-censorship or simply stopping work.

This trend is what caused Javier Valdéz to say “no to silence” and that is why today, we join the call #NiUnoMás.

Originally published in Global Voices.