Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Considered Response 3

Uploaded by

api-233902265Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Considered Response 3

Uploaded by

api-233902265Copyright:

Available Formats

Considered Response #3: The Need to Read: Literacy Instruction in the Twenty-First Century Andrew Butterworth Dr.

Catherine Broom Group #1 University of British Columbia Okanagan

Butterworth 1 Twenty-first century teachers must collectively reassess the meaning and importance of literacy if we are to have a positive impact on our students educational development. For the faculty of Kootenay Middle School, problems in adolescent literacy have come to the forefront. Students are misbehaving in class, not handing in assignments, and are unable to follow directions, stemming mainly from their struggle to engage with their reading. The grade 8s of KMS are reading two or three grade levels below expectations and are having difficulties inferencing, making connections with, determining the importance of, and understanding the vocabulary in the texts they are reading. In order to approach this issue, the faculty of KMS must re-examine the various texts within their content area, while producing engaging lesson plans that meet the needs of the digital generation (Jukes et al., 2010). Content-area teachers must also work in collaboration not only with literacy teachers, but also with one another, recognizing that certain texts are often interdisciplinary and can impact students learning across a variety of subjects. Likewise, certain content area teachers, such as Andy, must realize that literacy extends into their subject area, for example in the form of graphs, tables, and charts. An effective lesson plan for me is not one that simply engages with a variety of texts, but one that will connect with my students prior knowledge, process new information into their existing schemas, and then synthesize this information through self-reflection (Schnellert, 2013). That said, I dont believe the students at KMS are less intelligent than previous generations, rather their teachers are failing to produce an educational environment suitable to their needs.

Section 1: Re-defining Text and Literacy Traditionally, literacy and content area teaching have been regarded as separate matters (Draper and Siebert, 2010). Draper and Siebert argue that the practice of simply reading and

Butterworth 2 writing printed text is not effective in all content areas as some subjects negotiate different kinds of content in different ways (Draper and Siebert, 2010, 22). They suggest that the traditional definitions of text and literacy have caused the conflict between content area and literacy teachers and we must therefore broaden our definitions. Text should not be restricted to only printed materials, but should also include non-print, pictures, and audio content, while literacy refers to our ability to negotiate and create texts in discipline appropriate ways (Draper and Siebert, 2010, p. 27, 30). These wider definitions recognize that disciplines often engage with texts differently. In my experience, I never understood text as something other than printed material prior to exploring this case. One of the reasons behind my decision to pursue a degree in history, for example, was that I found the content more engaging and the texts easier to navigate. My Math 12 course, on the other hand, I found more difficult. I struggled reading the texts, such as the figures on my graphing calculator, mostly because the language and symbols were quite different than my courses in the humanities. Reflecting back on that course, I feel I could have had better results were I to engage myself more with the content or if I were to receive extra assistance with reading the various texts that were required. As a social studies teacher, I must help students navigate the variety of texts required to understand the subject. For example, in an average lesson, students should be able to read maps, understand a variety of vocabulary, and recognize the different styles of printed texts, such as narrative and informational (Doty et al., 2003). As Doty, Cameron, and Barton (2003) assert, rather than simply teach my students new content, I must first prepare them to read the texts used in my lesson. This can be accomplished by initially engaging my students with their prior knowledge. Fisher and Frey (2009) argue that existing knowledge is the key to reading

Butterworth 3 comprehension and that, as teachers, we must constantly guide students in developing and activating relevant background knowledge (Fisher and Frey, 2009, 6). When teaching literacy in my content area, I would use formative assessment to determine what my students know in order to better guide my instruction. I could connect students with their background knowledge of the subject by getting them to explore applicable texts that are meaningful to them. Based on what the students bring to the classroom in the way of prior knowledge, I could then better determine both the starting point and direction of my lesson plan. In a social studies classroom, this connecting phase could work through a variety of activities. In relation to different texts, for example, I could ask students to bring in a text that symbolizes their knowledge of a specific event in history. The purpose of this activity would not only be for myself to better understand my class background knowledge on the content, but also for the students to learn more about the different texts that are involved with social studies. There is also the potential in this activity to incorporate digital media into my lesson in the form of a historically relevant film for example. I could also incorporate vocabulary learning into this phase, such as the LINK strategy (Buehl, 2001). I would write a cue word in the middle of the board and have students contribute meaningful and related words, then have them discuss why they chose these words while making connections between each one of them.

Section 2: Engagement and Reading Comprehension In my opinion, the students at KMS are struggling with their reading primarily because they are not engaged with the texts and lessons that are being taught. Traditional teaching methods have led to a gap between students and teachers, as youth have instantaneous access to information and communication around the globe (Jukes et al., 2010, p. 10). Students are

Butterworth 4 spending more than 25 hours engaged with their digital media devices and are therefore tuning out at school (Jukes et al., 2010). Digital first language (DFL) adolescents can sense that their DSL teachers are out of touch with the digitalized world in which they live and are therefore struggling to immerse themselves in their education. In regards to literacy, Smith and Wilhelm (2002) argue that, in particular, boys are struggling with literacy more so than girls. This is due to a number of reasons, such as literacy not being associated with cultural ideals of masculinity, and is rather seen as feminine. Furthermore, it is suggested that this issue is related to the mismatch of texts in and out of the classroom, as boys practice literacy with electronic devices outside of school (Smith and Wilhelm, 2002, p. 14). It becomes imperative, therefore, to create a lesson that speaks to the DFL generation that builds on the skills that they have, specifically those with technology. From my experience in school, I found the most engaging lessons were those that were left relatively open ended, allowing me to explore a relevant topic of my choice through a text that interests me. I specifically remember a high school English class project in which we were asked to re-enact a scene from Macbeth in groups of five. I had to memorize my lines, which forced me to read and re-read the scene we selected. I also wanted to act my part, so I remember going online and watching filmic adaptations of the text to get an idea of what my choreography should look like. I was immersed in the subject, which allowed me to better understand the story as a whole. Furthermore, my teacher asked us to write a short collaborative paper on why we chose that scene and how it was significant to the play as a whole. Overall, this activity allowed me to engage with the material and determine the importance of the scene I was reading. In helping my students process new content and comprehend their reading, as a teacher I would put great emphasis on keeping my students engaged both with the texts they are reading as

Butterworth 5 well as with the lesson. This would be centered on group-based, collaborative activities and open ended assignments that allowed students to incorporate digital media. As part of the fifteen elements of effective literacy programs, Biancarosa and Snow (2006) assert that adolescent students need motivation and self-directed learning, access to a variety of texts, as well as a technological component. For me, motivation to read stems primarily from the type of lesson students have to engage with and the personality of the teacher in the classroom; I would therefore tend to favour open-ended projects that students could explore through self-direction. In a social studies classroom, for example, I could have students select a Renaissance artist or inventor during the Industrial Revolution, then have them present, in any way, on this individual. That way, students interested in technologies, such as Power Point, could incorporate those into their presentation, while students who favour written material could write a report instead. Each student has different skills and interests, and therefore specific and guided activities will not sufficiently meet each students needs.

Section 3: Collaboration In order for literacy instruction to be more effective, the faculty at KMS need to collaborate and teach literacy across each discipline. Biancarosa and Snow (2006) assert that students need extended time for literacy learning, two to four hours of instruction daily, thereby making interdisciplinary study a necessity. Brownlie and Schnellert (2009) write that teachers working in teams can identify the thinking skills that students need in order to expand while ensuring that students do not fall behind or receive conflicting messages about learning (pg. 18). This can be as simple as grade-wide teaching teams or content area and literacy teachers working together, creating lessons and activities that reach more learners (pg. 19). As high

Butterworth 6 school classes are often no longer integrated under one teacher, it becomes important for students to make connections across content areas. For the teachers of KMS, this could take the form of a collaborative lesson between two content-area teachers or between content area and literacy teachers. For example, Andy and Leland could each incorporate designing and reading blueprints into their lessons. In my discipline, I could use narrative texts or graphic novels from English class to supplement some of my discussion of an event in history. In my high school history class, for example, my teacher got us to read Maus, a graphic novel which looked at the experiences of a Holocaust survivor, while representing humans as different types of animals. One of the priorities for myself as a teacher would be to collaborate with my colleagues and integrate literacy instruction into my lesson. Brownlie and Schnellert (2009) write that cross-curricular teams are needed in order to make thinking skills a priority across classrooms (pg. 20). Through collaboration, the faculty at KMS could teach students literacy skills, such as inferring and making connections, while sharing information and building more comprehensive lesson plans.

Conclusion Literacy instruction is essential to education as it allows students to engage with the lesson and with the various texts that are required in each subject. My approach to teaching literacy in my content area would involve creating an engaging lesson and classroom environment that is structured around my students existing knowledge and that makes use of a variety of different texts, including digital media. I would also collaborate with other teachers and extend my literacy instruction to include other disciplines. In an engaging class, I could

Butterworth 7 better give my students the necessary reading comprehension instruction, such as techniques of detailed note-making (Biancarosa and Snow, 2006). The final stage of my lesson would be to synthesize my students information through activity based personal reflection. I could make use of a learning log, double-entry diary, a discussion web, partner discussion, or simply have students represent their thinking in different modes (Doty et al., 2003, Tovani, 2004). These strategies would teach students to make meaningful connections that could deepen their understanding of the text or texts used (Tovani, 2004, pg. 12). The students at KMS are not engaged with the current lessons taught at their school. It is important therefore that the teachers collaborate to create a more comprehensive approach to literacy instruction. They must revaluate their definition of texts while creating a more engaging classroom environment through loose and open-ended activities. Without proper literacy instruction, the faculty at KMS can expect to see the trend of lower reading levels continue.

Butterworth 8 References Biancarosa, C., & Snow, C. E. (2006). Reading nextA vision for action and research in Middle and high school literacy: A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York (2nded.).Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education. www.all4ed.org/files/ReadingNext.pdf Brownlie, F. & L. Schnellert (2009). It's all about thinking: Collaborating to support all learners in English, social studies and humanities. Winnipeg, MB: Portage and Main Press. Buehl, D. (2001). Classroom strategies for interactive learning. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Doty, J., Cameron, G., & M. Barton (2003).Teaching reading in social studies (2nd ed.) Aurora, Colorado: McREL. Draper,R. J., Broomhead, P., Jensen, A.P., Nokes, J.D., & D. Siebert (Eds.) (2010). (Re)Imagining content-area literacy instruction. New York: Teachers College Press. Fisher, D. & N. Frey (2009).Background knowledge: The missing piece of the comprehension puzzle. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Jukes, I.,McCain, T., & L. Crockett (2010). Understanding the digital generation: Teaching and learning in the new digital landscape. Kelowna, BC: 21st Century Fluency Project Inc. Schnellert, L. (2013). Language and Literacy [Lecture Notes]. Retrieved from blogs.ubc.ca Smith, M. W. & J. Wilhelm (2002). Whats going down: A review of the current concerns around boys and literacy. In Reading dont fix no Chevys: Literacy in the lives of young men. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Tovani, C. (2004). The so what? of reading comprehension. In Do I really have to teach reading? Content comprehension, grades 6-12. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chapter 8 Developing A Global Management Cadre: International Management, 9e (Deresky)Document34 pagesChapter 8 Developing A Global Management Cadre: International Management, 9e (Deresky)Christie LamNo ratings yet

- A Tale of Three Learning OutcomesDocument8 pagesA Tale of Three Learning OutcomesJaycel PaguntalanNo ratings yet

- Limits of EducationDocument21 pagesLimits of Educationbear clawNo ratings yet

- Polarity Therapy Student HandbookDocument23 pagesPolarity Therapy Student HandbookGg K0% (2)

- Brand Matters PresentationDocument24 pagesBrand Matters PresentationHanderson SoNo ratings yet

- HSC Science 8 Mahanagr PalikaDocument26 pagesHSC Science 8 Mahanagr PalikaLost OneNo ratings yet

- The National Service Training Program (R.A. 9163)Document16 pagesThe National Service Training Program (R.A. 9163)chan oracionNo ratings yet

- Background On Student Teaching: Aklan State University-College of Fisheries and Marine SciencesDocument8 pagesBackground On Student Teaching: Aklan State University-College of Fisheries and Marine SciencesJicelle Joy RicaforteNo ratings yet

- 1b Cas Interviews Worksheet Template and Sample 1Document2 pages1b Cas Interviews Worksheet Template and Sample 1Rania ShabanNo ratings yet

- Kevin P. Kerr 560 Nathan Roberts Road - Gray, GA 31032: Georgia College and State University, Milledgeville, GADocument1 pageKevin P. Kerr 560 Nathan Roberts Road - Gray, GA 31032: Georgia College and State University, Milledgeville, GAKevin2KerrNo ratings yet

- Elizabeth Hoyle Konecni - Sparking Curiosity Through Project-Based Learning in The Early Childhood Classroom - Strategies and Tools To Unlock Student Potential-Routledge - Eye On Education (2022)Document187 pagesElizabeth Hoyle Konecni - Sparking Curiosity Through Project-Based Learning in The Early Childhood Classroom - Strategies and Tools To Unlock Student Potential-Routledge - Eye On Education (2022)docjorseNo ratings yet

- Certification Manual 5 20180511Document51 pagesCertification Manual 5 20180511Grupo Musical EuforiaNo ratings yet

- Multicultura L Education: A Challenge To Global TeachersDocument12 pagesMulticultura L Education: A Challenge To Global TeachersRoldan Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- XXX Programme Faculty of XX XXX UniversityDocument2 pagesXXX Programme Faculty of XX XXX University王泽楠No ratings yet

- 3 How To Get FilthyDocument7 pages3 How To Get FilthyMary NasrullahNo ratings yet

- ACR of Classroom Meeting During Portfolio DayDocument3 pagesACR of Classroom Meeting During Portfolio DayPatricia Luz Lipata100% (1)

- LeannacrewsresumestcDocument3 pagesLeannacrewsresumestcapi-250337748No ratings yet

- DLP-Bohol - Science8 Q1 W2 D4Document2 pagesDLP-Bohol - Science8 Q1 W2 D4Valdeleon Taguiam CatherineNo ratings yet

- Learner Questionnaire For Online or Elearning Courses, C. R. WrightDocument5 pagesLearner Questionnaire For Online or Elearning Courses, C. R. Wrightcrwr100% (10)

- Divyanshi PDFDocument5 pagesDivyanshi PDFxyjgcfNo ratings yet

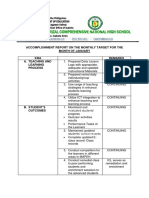

- Accomplishment ReportDocument2 pagesAccomplishment ReportAiza Rhea Santos100% (3)

- Emily Kallil ResumeDocument3 pagesEmily Kallil Resumeapi-350203150No ratings yet

- in Prof - Ed 9Document42 pagesin Prof - Ed 9Jenny Rose Rejano HilumNo ratings yet

- Notes For Letter of ExplanationDocument4 pagesNotes For Letter of ExplanationHHNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan-MicroteachingDocument2 pagesLesson Plan-MicroteachingSella RanatasiaNo ratings yet

- Action Plan in School LibraryDocument3 pagesAction Plan in School LibraryRosanno David93% (15)

- Elt Trends 2 in Asia PDFDocument5 pagesElt Trends 2 in Asia PDFmarindaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Pronunciation Without Using Imitation: Why and How - Messum (2012)Document7 pagesTeaching Pronunciation Without Using Imitation: Why and How - Messum (2012)Pronunciation ScienceNo ratings yet

- Licensure Examination For Teachers OrientationDocument17 pagesLicensure Examination For Teachers OrientationPaul EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Module 5 - The Project in The Organization StructureDocument7 pagesModule 5 - The Project in The Organization StructureJeng AndradeNo ratings yet