Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Setting Handout

Uploaded by

api-241330064Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Setting Handout

Uploaded by

api-241330064Copyright:

Available Formats

Huckleberry Finn Mark Twain 1884

The second night we run between seven and eight hours. With a current that was making over four mile an hour. We catched fish, and talked, and we took a swim now and then to keep off sleepinesss. It was kind of solemn, drifting down the big still river, laying on our backs looking up at the stars, and we didnt ever feel like talking loud, and it warnt often that we laughed, only a little kind of a low chuckle. We had mighty good weather, as a general thing, and nothing ever happened to us at all, that night, nor the next, nor the next. Every night we passed towns, some of them away up on black hillsides, nothing but just a shiny bed of lights, not a house could you see. The fifth night we passed St. Louis, and it was like the whole world lit up. In St. Petersburg they used to say there was twenty or thirty thousand people in St. Louis, but I never believed it till I see that wonderful spread of lights at two oclock that still night. There warnt a sound there; everybody was asleep.

True Grit Charles Portis 1968 I noticed that the houses in Fort Smith were numbered but it was no city at all compared to Little Rock. I though then and still think that Fort Smith ought to be in Oklahoma across the river then but of course it was not Oklahoma across the river then but the Indian Territory. They have that big wide street there called Garrison Avenue like places out in the west. The buildings are made of fieldstone and all the windows need washing. I know many fine people live in Fort Smith and they have one of the nations most modern waterworks but it does not look like it belongs in Arkansas to me. There was a jailer at the sheriffs office and he said we would have to talk to the city police or the High Sheriff about the particulars of Papas death. The sheriff had gone to the hanging. The undertaker was not open. He had left a notice on his door saying he would be back after the hanging. We went to the Monarch Boardinghouse but there was no one there except a poor old woman with cataracts on her eyes. She said everybody had gone to the hanging but her. She would not let us in to see about Papas traps. At the city police station we found two officers but they were having a fist fight and were not available for inquiries. Yarnell wanted to see the hanging but he did not want me to so he said we should go back to the sheriffs office and wait there until everybody got back. I did not much care to see it but I saw he wanted so I said no, we would go to the hanging but I would not tell Mama about it. That was what he was worried about.

The Hunger Games Suzanne Collins 2008 When I wake up, the other side of the bed is cold. My fingers stretch out, seeking Prims warmth but finding only the rough canvas cover of the mattress. She must have had bad dreams and climbed in with our mother. Of course she did. This is the day of the reaping .I prop myself up on one elbow. Theres enough light in the bedroom to see them. My little sister, Prim, curled up on her side, cocooned in my mothers body, their cheeks pressed together. In sleep, my mother looks younger, still worn but not so beaten-down. Prims face is as fresh as a raindrop, as lovely as the primrose for which she was named. My mother was very beautiful once, too. Or so they tell me. Sitting at Prims knees, guarding her, is the worlds ugliest cat. Mashed-in nose, half of one ear missing, eyes the colour of rotting squash. Prim named him Buttercup, insisting that his muddy yellow coat matched the bright flower. He hates me. Or at least distrusts me. Even though it was years ago, I think he still remembers how I tried to drown him in a bucket when Prim brought him home. Scrawny kitten, belly swollen with worms, crawling with fleas. The last thing I needed was another mouth to feed. But Prim begged so hard, cried even, I had to let him stay. It turned out OK. My mother got rid of the vermin and hes a born mouser. Even catches the occasional rat. Sometimes, when I clean a kill, I feed Buttercup the entrails. He has stopped hissing at me. Entrails. No hissing. This is the closest we will ever come to love. I swing my legs off the bed and slide into my hunting boots. Supple leather that has molded to my feet. I pull on trousers, a shirt, tuck my long dark braid up into a cap, and grab my forage bag. On the table, under a wooden bowl to protect it from hungry rats and cats alike, sits a

perfect little goats cheese wrapped in basil leaves. Prims gift to me on reaping day. I put the cheese carefully in my pocket as I slip outside. Our part of District 12, nicknamed the Seam, is usually crawling with coal miners heading out to the morning shift at this hour. Men and women with hunched shoulders, swollen knuckles, many of whom have long since stopped trying to scrub the coal dust out of their broken nails and the lines of their sunken faces. But today the black cinder streets are empty. Shutters on the squat grey houses are closed. The reaping isnt until two. May as well sleep in. If you can. Our house is almost at the edge of the Seam. I only have to pass a few gates to reach the scruffy field called the Meadow. Separating the Meadow from the woods, in fact enclosing all of District 12, is a high chain-link fence topped with barbed-wire loops. In theory, its supposed to be electrified twenty-four hours a day as a deterrent to the predators that live in the woods packs of wild dogs, lone cougars, bears that used to threaten our streets. But since were lucky to get two or three hours of electricity in the evenings, its usually safe to touch. Even so, I always take a moment to listen carefully for the hum that means the fence is live. Right now, its silent as a stone. Concealed by a clump of bushes, I flatten out on my belly and slide under a metre-long stretch thats been loose for years. There are several other weak spots in the fence, but this one is so close to home I almost always enter the woods here.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Native American Gods and Goddesses - North AmericaDocument7 pagesNative American Gods and Goddesses - North AmericaSharon CragoNo ratings yet

- Modern Pattern DesignDocument315 pagesModern Pattern DesignKristine91% (35)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Mount GundabadDocument73 pagesMount GundabadGuillaume MénagerNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Brighton Blanket PatternDocument16 pagesBrighton Blanket PatternMandy GrayNo ratings yet

- Clarkston (3 0)Document107 pagesClarkston (3 0)seanhend5No ratings yet

- Flea ControlDocument4 pagesFlea ControlwandererNo ratings yet

- Sherlock 3x02 - The Sign of Three PDFDocument95 pagesSherlock 3x02 - The Sign of Three PDFurka urkaNo ratings yet

- Little Footsteps - Ted TallyDocument7 pagesLittle Footsteps - Ted TallyMaster_HeideggerNo ratings yet

- (Alison Darren) Lesbian Film Guide (Sexual Politics)Document257 pages(Alison Darren) Lesbian Film Guide (Sexual Politics)Andreea0% (1)

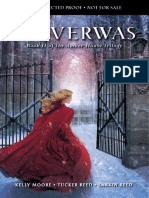

- Neverwas - Kelly MooreDocument323 pagesNeverwas - Kelly MooreFernandaMirabileNo ratings yet

- Takamaz X-10i E F21iTB 002aDocument290 pagesTakamaz X-10i E F21iTB 002aAle_blessed80% (5)

- Jurassic Park 4: Dark ContinentDocument97 pagesJurassic Park 4: Dark ContinentCharles PatersonNo ratings yet

- Sced 4989 Professional Development and Leadership AssignDocument4 pagesSced 4989 Professional Development and Leadership Assignapi-241330064No ratings yet

- Argumentation OutlineDocument1 pageArgumentation Outlineapi-241330064No ratings yet

- Intro para GoDocument2 pagesIntro para Goapi-241330064No ratings yet

- Prewriting 5 StepsDocument5 pagesPrewriting 5 Stepsapi-241330064No ratings yet

- FinalDocument8 pagesFinalapi-241330064No ratings yet

- Hamlet and HarleysDocument6 pagesHamlet and Harleysapi-241330064No ratings yet

- Life After Polygamy Final DraftDocument12 pagesLife After Polygamy Final Draftapi-241330064No ratings yet

- CM AW15 Brochure Web PricedDocument72 pagesCM AW15 Brochure Web PricedromyluleNo ratings yet

- Bromine MSDSDocument8 pagesBromine MSDSsunil_vaman_joshiNo ratings yet

- Heer Ranjha: Name: Iffra Khan Roll Num: 103Document7 pagesHeer Ranjha: Name: Iffra Khan Roll Num: 103amna khanNo ratings yet

- Material Safety Data Sheet: Page 1 of 3 AB-80Document3 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet: Page 1 of 3 AB-80Denise AG100% (1)

- 5 Letters CSW 2012Document65 pages5 Letters CSW 2012Anton_Giardhi_3734No ratings yet

- Stage DirectionsDocument5 pagesStage DirectionsNiki Li100% (1)

- Pfaff SZA-645F Sewing Machine Instruction ManualDocument45 pagesPfaff SZA-645F Sewing Machine Instruction ManualiliiexpugnansNo ratings yet

- Crisis, Economics, and The Emperor's ClothesDocument201 pagesCrisis, Economics, and The Emperor's ClothesFrans DoormanNo ratings yet

- Cerruti CollectionsDocument5 pagesCerruti CollectionsPhan LeNo ratings yet

- MGT Assignment On Bata Shoes BDDocument18 pagesMGT Assignment On Bata Shoes BDbabur raiyan75% (4)

- Myanmar: A. GeographyDocument13 pagesMyanmar: A. GeographyJamiah Obillo HulipasNo ratings yet

- Tender Niftem HousekeepingDocument27 pagesTender Niftem HousekeepingD S RajawatNo ratings yet

- SAPS - Root Tip Mitosis For A-Level Set Practicals - Student NotesDocument4 pagesSAPS - Root Tip Mitosis For A-Level Set Practicals - Student NotesRashida HanifNo ratings yet

- Trump OutsourcingDocument264 pagesTrump OutsourcingJon WardNo ratings yet

- Brief Industrial Profile of KANNUR District: MSME-Development Institute, ThrissurDocument20 pagesBrief Industrial Profile of KANNUR District: MSME-Development Institute, ThrissurSaad AbdullaNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 4 - SetsDocument3 pagesWorksheet 4 - SetsAhmed KhanNo ratings yet

- Employer's Guide To Bradford GoodwinDocument24 pagesEmployer's Guide To Bradford GoodwinBradford Reid GoodwinNo ratings yet

- Apparel Manufacturing Engineering - II: MD - Abir Hasan Khan (172-055-0-155)Document18 pagesApparel Manufacturing Engineering - II: MD - Abir Hasan Khan (172-055-0-155)Md. Samin Ahmed SaminNo ratings yet