Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Educ 352 - Lit Review Final 2

Uploaded by

api-242132506Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Educ 352 - Lit Review Final 2

Uploaded by

api-242132506Copyright:

Available Formats

!"##$#%&'()*+&,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.

61&4-7&16/8961566:&

;&

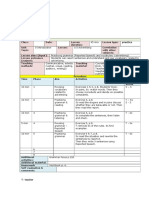

Inclusion Practices and Self-Esteem: Possible Impact on Students with Learning Disabilities Rachel Knoepfle University of the Pacific

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

<&

Inclusion Practices and Self-Esteem: Possible Impact on Students with Learning Disabilites The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) recommends that, to the extent that it is appropriate, children with disabilities are educated with their same-age peers and not removed from the general education classroom (United States Department of Education, 2004). The practice of inclusion, which situates students with disabilities alongside their nondisabled (ND) peers, is implemented throughout the American public school system in accordance with the law. Inclusion placement is a decision made by an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) team, and is highly individualized and personalized to the student. Students who qualify for special education services under IDEA have IEPs, and teams meet annually to review services and make changes as needed; IEP teams are made up of school administrators, special and general education teachers, the parents of the student, and other appropriate personnel, which can include the school psychologist, the school nurse, behavior specialists and other personnel as needed. Placement decisions in inclusion settings are often influenced by the idea that placement in general education classrooms will improve social functioning (Vaughn, Elbaum & Schumm, 1996). Students with learning disabilities who are included in the general education classroom are participating in a practice that can emphasize the differences between themselves and their ND peers, which can affect the self-esteem of the student being included (Madge, Affleck, & Lowenbraun, 1990; Ribner, 1978). Studies have shown that students with learning disabilities have lower self-esteem and/or self-concept compared to their ND peers in general (Cosden, Elliott, Nobel, & Keleman, 1999; Heyman, 1990; MacMaster, Donovan, & MacIntyre, 2002), as well as specifically in inclusion settings (Bear, Clever, & Proctor, 1991; Clever, Bear, &

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

=&

Juvonen, 1992; Daniel & King, 1997). Thus, class placement does affect the self-esteem of the student being included (Ribner, 1978); these affects can be seen in specific areas such as academic and cognitive competence or how well a student meets academic goals and standards (Banerji & Dailey, 1995; Bear, Clever, Proctor, 1991; Clever, Bear, & Juvonen, 1992; Grolnick & Ryan, 1990; Priel & Leshem, 1990; Vaughn, Elbaum, & Schumm, 1996), and social and emotional functioning (Madge, Affleck, & Lowenbraun, 1990; Shoho, Katims, & Wilks, 1997; Vaughn, Elbaum, & Schumm, 1996; Wiener & Tardif, 2004). When broken down into categories, self-esteem, although it is impacted by inclusion, may be lower, higher, or the same as that of ND peers. Overall global self-esteem is looked at as well, and when it is separated from academic factors, global self-esteem in students with learning disabilities in inclusion settings is the same as that of their ND peers (Ntshangase, Mdikana, & Cronk, 2008). Typically, the rational for inclusion placements for students with learning disabilities is that overall social functioning and peer acceptance will improve in a general education setting (Vaughn, Elbaum & Schumm, 1996), but overall social functioning and peer acceptance do not always improve in such settings (Madge, Affleck, & Lowenbraun, 1990; Priel & Leshem, 1990; Wiener & Tardif, 2004). Investigating the perceptions of the consumers of full inclusion services seems appropriate (Shoho, Katims & Wilks, 1997). Definitions Both the field of special education and the study of self-esteem contain terms that need specific definitions. Savichs (2008) definitions inclusion as: made up of four main components: 1) all students receive their education in their home school; 2) placement is based upon the concept of natural proportions; 3) there is

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

>&

learning/teaching restructuring so that supports are created for special education in the general education setting; and 4) placements are grade- and age-appropriate (p. 2). There is not a specific reference in Savichs definition as to how much time an included student spends in a general education class. The United States Department of Education divides the amount of time spent outside the general class into three categories: less than 40 percent of class time spent outside of general education, 40-79 percent of class time spent outside of general education, and more than 80 percent of class time spent outside of general education (USDE, 2012b). Thus, the length of time for which a special education student can be included can and does vary. Literature on the social effects of inclusion encompasses the following terms: selfesteem, self-concept, self-perception, and self-determination. Rosenberg (1971), articulated the difficulties of defining self-esteem: an agreement . . . regarding the importance of the self or self-concept appears to be accompanied by an equally widespread disagreement about what it is. Thus, various terms have been bandied about self, self-concept, self-image, self-esteem. He goes on to offer this definition: The self is an attitude toward an object. Our chief . . . concern is the individuals positive or negative orientation toward this object, his favorable or unfavorable attitudes toward it, and the associated emotional reactions. Essentially, this is what is meant by self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1971). Unless otherwise specified by a particular study, Rosenbergs definition of self-esteem will be used to provide meaning for the terms self-concept and self-perception. Inclusion of students with learning disabilities is the focus of much research (Banerji & Dailey, 1991; Bear, Clever, & Proctor, 1991; Clever, Bear, & Juvonen, 1992; Daniel & King,

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

?&

1997; Madge, Affleck, & Lowenbraun, 1990; Ntshangase, Mdikana, & Cronk, 2008; Shoho, Katims, & Wilks, 1997). The IDEA eligibility category, Specific Learning Disability (SLD), is defined as a disorder involved in understanding or in using language that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations (National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities [NICHCY], 2012). SLD does not include learning problems that are primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities; of intellectual disability; of emotional disturbance; or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage, (NICHCY, 2012). Background The most recent statistics from the United States Department of Education regarding the number of students with disabilities served is from the fall of 2010, and reports that at that time 6,419,000 students received special education services under IDEA, which has thirteen categories of eligibility (United States Department of Education [USDE], 2012a), and 14.2% of those students spent less than 40% of the school day outside the general classroom (USDE, 2012b). Approximately 2,357,000 students with specific learning disabilities eligibility (USDE, 2012a) received services in the fall of 2010, and 7.3% of those students are included for more than 60% of their school day (USDE, 2012b). Over 2.3 million children with specific learning disabilities are spending most of their school day in a general education classroom, an experience which has affected their self-esteem and self-concept in disparate ways and to varying degrees (Ribner, 1978). Discussion When researching inclusion, there are a number of articles on inclusion practices, with focus on teachers and techniques, general education students, and students with disabilities

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

@&

(Bennett, Deluca, & Bruns, 1997; Chadsey & Gun Han, 2005; Fox & Ysseldyke, 1997; Vaughn, Schumm, & Kouzekanani, 1993), as well as several studies regarding the effects of inclusion on the self-esteem of students with disabilities (Bear, Clever, & Proctor, 1991; Clever, Bear, & Juvonen, 1992; Daniel & King, 1997; Ntshangase, Mdikana, & Cronk, 2008), and the general social effects of inclusion (Banerji & Dailey, 1995; Madge, Affleck, & Lowenbraun, 1990; Shoho, Katims, & Wilks, 1997; Wiener & Tardif, 2004). These effects can be broken down into two categories: effects on academic and/or cognitive competence, and effects on social and emotional functioning. When looking at overall self-esteem or self-worth in included students with disabilities studies have shown both lower scores of self-esteem as compared to peers (Bear, Clever & Proctor, 1991; Daniel & King 1997) and no difference in self-esteem as compared to peers (Ntshangase, Mdikana, & Cronk, 2008). This may be explained by the classroom environment (Ntshangase, Mdikana, & Cronk, 2008) and academic ability (Bear, Clever, & Proctor, 1991). A more positive, encouraging environment can help to mediate feelings of low self-worth (Ntshangase, Mdikana, & Cronk, 2008). Likewise, deficits in scholastic and behavioral conduct, which are proven to be present in children with learning disabilities and which correspond to negative self-perceptions, could be the cause of low feelings of self-worth (Bear, Clever & Proctor, 1991; Daniel & King, 1997). Academic/Cognitive Competence When compared to their ND peers across group settings, students with learning disabilities show low self-perceptions of cognitive competence (Priel & Leshem, 1990). This holds true for students with learning disabilities in inclusion settings as well (Bear, Clever & Proctor, 1991; Grolnick & Ryan, 1990). Along with low self-perceptions of cognitive

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

A&

competence, included students with learning disabilities also show low self-perceptions of academic competence (Clever, Bear & Juvonen, 1992; Vaughn, Elbaum & Schumm, 1996). In this particular area, self-perceptions may impact self-esteem because self-perceptions of scholastic competence are important to the feelings of self-worth among school-age children (Bear, Clever & Proctor, 1991). This is important information to keep in mind when making placement decisions as inclusion placement can highlight differences and deficiencies that can lead to lower feelings of self-worth (Bear, Clever, & Proctor, 1991). Academics are one of a classroom teachers biggest priorities and teachers who understand that academic struggles impact more than just a students grade will be better equipped to meet academic and emotional needs. Social and Emotional Functioning Given that inclusion has become a common practice since IDEAs authorization, studies have been conducted to determine the social impacts of inclusion on students with SLD in full day placement versus pull out placement (Shoho, Katims, & Wilks, 1997; Wiener & Tardif, 2004), as well as students with SLD in full day placement versus their ND peers (Madge, Affleck, & Lowenbraun, 1990; Vaughn, Elbaun, & Schumm, 1996). In both cases studies looked at peer acceptance, reciprocal friendships, and loneliness and perceptions of alienation. With regards to full inclusion placement, research findings support the idea that students with learning disabilities are less accepted by their ND peers, that is ND students accept ND students to a strong degree than ND students accept students with learning disabilities, as measured by students without disabilities ranking their classmates, both with and without SLD (Madge, Affleck, & Lowenbraun, 1990). When comparing peer acceptance between inclusion and self-contained placements, there were no differences (Priel & Leshem, 1990; Wiener &

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

B&

Tardif, 2004). Students with disabilities who receive support in a general education classroom are better accepted by their peers than students who are pulled out of the classroom to receive services (Wiener & Tardif, 2004). Peer acceptance, then, can fluctuate given the classroom setting and service delivery. Typically, these results are determined by students ranking their peers in order of preference (Madge, Affleck, & Lowenbraun, 1990; Wiener and Tardif, 2004), which can indicate that students with SLD are not aware of the levels of peer acceptance. In an inclusion setting, reciprocal friendships were measured and results were broken down into categories for students with LD, students who are low achieving (LA), and students who are average/high achieving (AHA) (Vaughn Elbaum, & Schumm, 1996). Reciprocal friendships are defined as friendships in which two students have nominated each other as one of their three most-liked classmates (Vaughn Elbaum, & Schumm, 1996). Taking measurements in the fall and spring, students with LD made great gains, jumping from 26% of students reporting at least one reciprocal friendship to 53% of students reporting reciprocal friendships, which stands out compared to the other groups (Vaughn Elbaum, & Schumm, 1996). The AHA group showed a 9% increase, while the LA group reported a 13% decline (Vaughn Elbaum, & Schumm, 1996). Of particular note is the fact that the LD students reported reciprocal friendships with students who represented all achievement groups (Vaughn Elbaum, & Schumm, 1996), indicating that, in an inclusion placement, students can and do form meaningful friendships with their ND peers. Compared to students in self-contained settings, included students with disabilities perceive their best school friendships as higher in companionship and, therefore, of a higher quality (Wiener & Tardif, 2004). In looking only at students with disabilities and feelings of alienation, the findings vary significantly (Shoho, Katims, & Wilks, 1997). As students who are pulled out of class reported

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

C&

higher levels of alienation than peers who are fully included in the regular classroom, full inclusion can mediate some of the alienation that can be associated with having a learning disability (Shoho, Katims, & Wilks, 1997). When looking at comparisons between students who are fully included and students who are in self-contained placements, included students reported lower levels of loneliness (Wiener & Tardif, 2004). Implications According to the most recent statistics from the U.S. Department of Education, approximately 2.3 million students with specific learning disabilities received special education services during the 2010-2011 school year, and 7.3% of that group was included in the general education classroom for more than 60% of the school day (USDE, 2012a; USDE, 2012c). Classroom placement affects the self-esteem of the student being included (Ribner, 1978) in academic and social areas. Students with learning disabilities are more likely to struggle academically than their ND peers, and for students who are included into general education classes differences are highlighted, which can lead to lower self-perceptions of ability and lower overall self-esteem and self-worth (Bear, Clever, & Proctor, 1991; Daniel & King, 1997). While self-esteem may be lower in included students with learning disabilities (Daniel & King, 1997), when looking at inclusion placements and specifying between global self-esteem and selfperceptions in a given area, global self-esteem is not lower (Banerji & Dailey, 1995), but rather, self-perceptions of cognitive competence are lower (Grolnick & Ryan, 1990; Priel & Leshem, 1990). The social affects of inclusion on students with disabilities fall into different areas. Included students have access to and form high quality, reciprocal relationships with their ND peers (Vaughn, Elbaum & Schumm, 1996; Wiener & Tardif, 2004). Peer acceptance varies by classroom setting and service delivery; fully included students with learning disabilities are less

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

;D&

accepted by their classmates than ND students (Madge, Affleck & Lowenbraun, 1990), whereas students with learning disabilities who are fully included are more accepted than their peers who are pulled out to receive services (Weiner & Tardif, 2004). As arguments supporting inclusion generally center around the benefits derived both academically and socially for children with disabilities (Daniel & King, 1997; Vaughn, Elbaum & Schumm, 1996) it is important to note the actual social benefits of inclusion, as well as the effects on the students self-esteem and self-worth when making placement decisions. Classroom teachers who are aware of the impact of inclusion on academic self-perceptions will be better equipped to meet the needs of struggling students and provide support (Banerji & Dailey, 1995). Classroom teachers can also benefit from understanding the feelings of alienation and loneliness that included students may feel, as well encouraging the quality relationships that do form between included students with and without disabilities (Wiener & Tardif, 2004). More research and comparison among placement settings as they relate to the social and emotional functioning of students with learning disabilities would allow IEP teams to be better informed about the effects of inclusion when making decisions (Banerji & Dailey, 1995; Weiner & Tardif, 2004). Given the many factors involved academically and socially in including students with learning disabilities into the general education classroom, and the varying service delivery models, there is some controversy regarding the degree to which placement has an impact on social and emotional functioning, which prompts the need for more research and in more settings (Wiener & Tardif, 2004).

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:& References

;;&

Banerji, M. & Dailey, R.A. (1995). A study of the effects of the inclusion model on students with specific learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 28 (8), p. 511-522. Bear, G., Clever, A., & Proctor, W. (1991). Self-perceptions of nonhandicapped children and children with learning disabilities in integrated classes. Journal of Special Education, 24 (4), p. 409-426. Bennett, T., Deluca, D., & Bruns, D. (1997). Putting inclusion into practice: perspectives of teachers and parents. Exceptional Children, 64 (1), p. 115-131. Chadsey, J. & Gun Han K. Friendship-facilitation strategies: what do students in middle school tell us? Teaching Exceptional Children, Nov./Dec. 2005, p.52-57. Clever, A., Bear, G. & Juvonen, J. (1992). Discrepancies between competence and importance in self-perceptions of children in integrated classes. The Journal of Special Education, 26 (2), p. 125-138. Cosden, M., Elliott, K, Nobel, S., & Keleman, E. (1999). Self-understanding and self-esteem in children with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 22 (4), p. 279-290. Ntshangase, S., Mdikana, A., & Cronk, C. (2008). A comparative study of the self-esteem of adolescent boys with and without learning disabilities in an inclusive school. International Journal of Special Education, 23 (2), p. 75-84. Daniel, L. & King, D. (1997). Impact of inclusion education on academic achievement, student behavior and self-esteem, and parent attitudes. Journal of Education Research, 91 (2), p. 67-80. Fox, N.E. & Ysseldyke, J.E. (1997). Implementing inclusion at the middle school level: lessons from a negative example. Exceptional Children, 64 (1), p. 81-98.

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

;<&

Grolnick, W. & Ryan, R. (1990). Self-perceptions, motivation, and adjustment in children with learning disabilities: a multiple group comparison study. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23 (3), p. 177-184. MacMaster, K., Donovan, L., & MacIntyre, P. (2002). The effects of being diagnosed with a learning disability on childrens self-esteem. Child Study Journal, 32, 101-108. Madge, S., Affleck, J. & Lowenbraun, S. Social effects of integrated classrooms and resource room/regular class placements on elementary students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23 (7), p. 439-445. National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities. (2012). Categories of Disability Under IDEA. Retrieved from http://nichcy.org/disability/categories. Priel, B. & Leshem, T. (1990). Self-perceptions of first- and second- grade children with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilites, 23 (10), p. 637-642. Savich, C. (2008). Inclusion: The Pros and Cons: A Critical Review. Oakland University, CA: Author. Shoho, A., Katims, D, & Wilks, D. Perceptions of alienation among students with learning disabilities in inclusive and resource settings. High School Journal, 81 (1), p. 28-37. Ribner, S. (1978). The effects of special class placement on the self-concept of exceptional children. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 11 (5), p. 60-64. Rosenberg, M. (1971) Black and white self-esteem: The urban school child. Washington, D.C.: American Sociological Association. United States Department of Education. (2004). Building the legacy: IDEA 2004 [Data file]. Retrieved from

,-./01,2-&3!4.5,.61&4-7&16/8961566:&

;=&

http://idea.ed.gov/explore/view/p/%2Croot%2Cstatute%2CI%2CB%2C612%2Ca%2C5 %2CA%2C. United States Department of Education. (2012b). Digest of education statistics [Data file]. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_050.asp. United States Department of Education. (2012a). Digest of Education Statistics [Data file]. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_048.asp. Vaughn, S., Elbaum, B. E., & Schumm, J.S. (1996). The effects of inclusion on the social functioning of students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29 (6), p. 598-608. Vaughn, S., Schumm, J.S., & Kouzakanani, K. (1993). What do students with learning disabilities think when their general education teachers make adaptations? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 26 (8), p. 545-555. Wiener, J. & Tardif, C. (2004). Social and emotional functioning of children with learning disabilities: does special education placement make a difference? Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 19 (1), p. 20-32.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Educ 352 Biases Assumptions and EthicsDocument4 pagesEduc 352 Biases Assumptions and Ethicsapi-242132506No ratings yet

- Educ 352 Theory FrameworkDocument8 pagesEduc 352 Theory Frameworkapi-242132506No ratings yet

- ResumeDocument2 pagesResumeapi-242132506No ratings yet

- Educ 352 Good Research FinalDocument2 pagesEduc 352 Good Research Finalapi-242132506No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Traditional Assessment ReportDocument33 pagesTraditional Assessment ReportJyra Mae Taganas50% (2)

- Letter Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesLetter Lesson Planapi-389758204No ratings yet

- Rhythmic Activities Syllabus Outlines Course OutcomesDocument5 pagesRhythmic Activities Syllabus Outlines Course OutcomesTrexia PantilaNo ratings yet

- English RPH Year 3Document17 pagesEnglish RPH Year 3Sekolah Kebangsaan SekolahNo ratings yet

- Презентация по стилистикеDocument17 pagesПрезентация по стилистикеIryna ShymanovychNo ratings yet

- Politics and Administration Research Review and Future DirectionsDocument25 pagesPolitics and Administration Research Review and Future DirectionsWenaNo ratings yet

- Etp 87 PDFDocument68 pagesEtp 87 PDFtonyNo ratings yet

- Pangarap Pag Asa at Pagkakaisa Sa Gitna NG PandemyaDocument2 pagesPangarap Pag Asa at Pagkakaisa Sa Gitna NG Pandemyamarlon raguntonNo ratings yet

- PMG 324 Resource Managment PlanDocument9 pagesPMG 324 Resource Managment Planapi-719624868No ratings yet

- English Grammar and Correct Usage Sample TestsDocument2 pagesEnglish Grammar and Correct Usage Sample TestsOnin LaucsapNo ratings yet

- Ba Notes On Principles of Management Course. 1Document123 pagesBa Notes On Principles of Management Course. 1Jeric Michael Alegre75% (4)

- Improving Learning in MathsDocument66 pagesImproving Learning in MathsReinaldo Ramirez100% (1)

- Transfer Task in Practical ResearchDocument33 pagesTransfer Task in Practical Researchkim adoraNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Spelling and Reading Fluency/ComprehensionDocument22 pagesRelationship Between Spelling and Reading Fluency/ComprehensionRyann LeynesNo ratings yet

- Group Work 1 1Document21 pagesGroup Work 1 1hopeboyd36No ratings yet

- Curry Lesson Plan Template: ObjectivesDocument4 pagesCurry Lesson Plan Template: Objectivesapi-310511167No ratings yet

- HR Analytics UNIT 1Document7 pagesHR Analytics UNIT 1Tommy YadavNo ratings yet

- Creative Art Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesCreative Art Lesson Planapi-252309003No ratings yet

- 8 Dr. Anita BelapurkarDocument7 pages8 Dr. Anita BelapurkarAnonymous CwJeBCAXp100% (1)

- Understanding Cooperative Learning StructuresDocument35 pagesUnderstanding Cooperative Learning StructuresJenny Rose AguilaNo ratings yet

- 5 Focus 4 Lesson PlanDocument2 pages5 Focus 4 Lesson PlanMarija TrninkovaNo ratings yet

- Power and solidarity in languageDocument2 pagesPower and solidarity in languageJalal Nasser SalmanNo ratings yet

- 1 The Deeper Work of Executive DevelopmentDocument22 pages1 The Deeper Work of Executive DevelopmentAnushree GhoshNo ratings yet

- Ch02 PPTDocument14 pagesCh02 PPTMdeeq AbdullahiNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Tools & Summary of Findings: Jennifer A. Avila P2 / Palo Iii DistrictDocument30 pagesEvaluation Tools & Summary of Findings: Jennifer A. Avila P2 / Palo Iii DistrictJonathan QuintanoNo ratings yet

- Analytical GrammarDocument28 pagesAnalytical GrammarJayaraj Kidao50% (2)

- Fuzzy Logic Controller and Applications: Presented byDocument32 pagesFuzzy Logic Controller and Applications: Presented byAyush SharmaNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence Machine Learning 101 t109 - r4Document6 pagesArtificial Intelligence Machine Learning 101 t109 - r4Faisal MohammedNo ratings yet

- CWTS: Values EducationDocument6 pagesCWTS: Values EducationLeah Abdul KabibNo ratings yet

- Gumaca National High School's Daily Math Lesson on Quadratic EquationsDocument4 pagesGumaca National High School's Daily Math Lesson on Quadratic EquationsArgel Panganiban DalwampoNo ratings yet