Professional Documents

Culture Documents

General Public Article

Uploaded by

api-251486092Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

General Public Article

Uploaded by

api-251486092Copyright:

Available Formats

Mariana Covarrubias 1935127 March 2014 Issue Vol. 15 No.

The Role of Vitamin C and Zinc In Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment

By Mariana Covarrubias

Each year in the United States, 1 to 3 million people develop pressure ulcers.1 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicates that hospitalizations related to pressure ulcers increased 80 percent from 1993 to 2006.2,3 In healthcare facilities pressure ulcers are seen as indicators of inadequate care or low quality service. Attention to this issue is of great importance since complications related to pressure ulcers can result in sepsis, shock, or death.4 More than 2.5 million patients in United States health care facilities suffer from pressure ulcers, and 60,000 die from complications related to pressure ulcers each year.5 In the elderly pressure ulcers increase length of hospital visits and also increase risk of death by up to 400%.6 Dietitians play a vital role in combating malnutrition, usually a big cofactor associated with pressure ulcer development. Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH) Pressure ulcers are areas of damaged tissue and skin that most commonly affect the elderly population.7 Usually seen in hospitals, long term care facilities, and nursing homes, they are generally caused by friction, pressure, or moisture on the skin combined with underlying issues like low immune system, decreased lean body mass, low mobility, and malnutrition.4 In 2009, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) provided a new classification

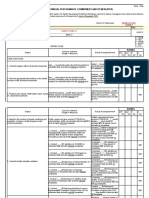

system and guidelines for pressure ulcer treatment. The severity of pressure ulcers is determined by their placement on the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing, the scale ranges from 0-17, seventeen being the most severe.1 The PUSH scale is used as a way to assess the healing of pressure ulcers and therefore the effectiveness of oral supplements. In a study in The Journal of Nutrition, pressure ulcers were treated with an oral supplement containing both vitamin C and zinc, the supplementation increased healing rate in comparison to the control group as evidenced by the ratings on the PUSH scale.

The Role of Vitamin C and Zinc Malnutrition can delay healing and increase the risk of chronic pressure ulcers, nutrition strategies like food fortification and oral nutritional supplements are often recommended. 8 Vitamin C helps rebuild collagen, it is important for tissue regeneration and repair.9 When a patient develops a pressure ulcer, usually they are malnourished and have low immunity.10 Malnutrition is a big cofactor in the development of pressure ulcers, and usually also includes deficiencies in certain macro and micro nutrients. A vitamin C deficiency is decreases collagen function, which causes delayed healing and impaired immunity.10 Although vitamin C by itself has not increased healing time in pressure ulcers, when combined with zinc and other micronutrients it has proven beneficial.3 Zinc is a mineral associated with protein synthesis, collagen formation, and cell generation.11 Zinc deficiency may be the result of malnutrition and can cause impaired healing and immune function.11 Research indicates that the rate of pressure ulcer healing accelerates when a wound healing supplement containing zinc, arginine, and vitamin C is administered, making it more preferable than a regular supplement.1

Prevention and Treatment Strategies For the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers, nutrition is an important part of a complete care plan.1,12,13 Adequate calories, protein, fluids, vitamins and minerals, should be provided because they are required by the body for maintaining tissue regeneration and preventing breakdown. Known risk factors for pressure ulcer development include undernutrition, unintended weight loss, impaired ability to eat independently, low BMI, and dehydration.7,15 Elderly patients who are malnourished are at a higher risk of developing pressure ulcers, dietitians play a critical role in correcting any nutrient deficiencies associated with malnutrition. The treatment of pressure ulcers with an oral supplement containing vitamin C and zinc provided successful results in comparison to just increasing calories or providing oral supplements not specific to wound healing.4 Nutrition screening helps identify individual with compromised nutritional status. According to the American Dietetic Association initial screening is completed upon admission and based on the results of the nutrition screening, a referral is made for a formal assessment by an RD. The RD then conducts a nutritional assessment and makes recommendations for management and interventions. Since most of these patients are malnourished it is recommended that patients receive oral supplementation containing vitamin C and zinc with continued followups upon the smallest change. Where Dietitians Fit In As mentioned, dietitians play an integral role in helping prevent and treat pressure ulcers. To change statistics, RDs must take on a more active role in this issue by staying on top of the latest research, so that they can help patients prevent pressure ulcers. In addition to educating themselves, RDs can educate nurses and doctors and counsel patients on the role nutrition has in

preventing and treating pressure ulcers. According to Becky Dorner, RD, LD all individuals should have a nutritional assessment upon admission and at the slightest condition change. The following medical nutrition therapy recommendations for pressure ulcers are provided by the NPUAP:

At admission each patient with a pressure ulcer should be screened and assessed for nutritional status and follow-up should occur at the slightest condition change or until completely healed.

All patients should be referred to a dietitian immediately for assessment and nutrition intervention.

Assess patients weight loss and weight history. Assess the patients ability to eat independently. Evaluate total food and fluid intake and provide adequate calories(30-35 kcals/kg body weight), make sure to adjust according to stress factors, weight loss, weight gain, and obesity level.

Liberalize diet restrictions when not enough calories consumed because of restrictions. Provide supplement or enhanced foods between meals, if needed. If necessary, consider enteral or parenteral nutrition when inadequate oral intake. Adequate protein (1.25-1.5 g/kg) should be provided to promote pressure ulcer healing. Constantly asses changes in condition and re-assess nutrition intervention according to goals. Make sure to evaluate renal function if high protein levels are recommended.

Encourage appropriate hydration and monitor constantly for signs of dehydration. Additional fluids should be provided for patients with dehydration, elevated temperature, vomiting, or diarrhea.

Encourage a balanced diet including good sources of vitamins and minerals. Make sure to offer vitamin and mineral supplements when malnourished or when deficiencies are confirmed.

It Takes More Than An RD Strong evidence points out that pressure ulcers have become a great concern, creating a significant health risk for patients. As part of the strategy to find a solution to this issue, RDs are essential in helping manage and treat pressure ulcers through supplementation and adequate nutrition. As the primary nutrition professional, dietitians must continue to work with the medical community to help prevent further complications and deaths from pressure ulcers. Mariana Covarrubias, Dietetics and Nutrition Student at Florida International University

References 1.Thomas DR, Goode PS, Tarquine PH, Allman RM. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers and risk of death. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:1435-1440. 2. Russo CA, Steiner C and Spector W.Hospitalizations Related to Pressure Ulcers among Adults 18 Years and Older, 2006.Healthcare Cost Utilization Project. December 2008. Available at: http://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb64.jsp. Accessed December 22, 2008. 3. Cuddigan J, Ayello EA, Sussman C, Baranoski S, eds. Pressure Ulcers in America: Prevalence, Incidence, and Implications for the Future. Reston, VA: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; 2001. 4. Van Anholt RD, Sobotka L, Meijer EP, Heyman H, Goren HW, Topinkova E, Van Lean M, Schols JM. Specific nutritional support accelerates pressure ulcer healing and reduces wound care intensity in non-malnourished patients. Nutrition. 2010;26(9):867-72. 5. Strategies for Preventing Pressure Ulcers, Joint Commission Perspectives on Patient Safety, Volume 8, Number 1, January 2008, pp.5-7(3). http://www.jcrinc.com/Pressure-Ulcers-stageIIIIV-decubitis-ulcers/. Accessed March 23, 2009. 6. Management of chronic pressure ulcers: an evidence-based analysis. Ontario health technology assessment series. 2009;9(3):1-203. 7. Theilla M, Singer P, Cohen J, Dekeyser F. A diet enriched in eicosapentanoic acid, gammalinolenic acid and antioxidants in the prevention of new pressure ulcer formation in critically ill patients with acute lung injury: A randomized, prospective, controlled study. Clin Nutr. 2007;26(6):752-757. 8. Bauer J, D., Isenring E, Waterhouse M. The effectiveness of a specialised oral nutrition supplement on outcomes in patients with chronic wounds: a pragmatic randomised study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26(5):452-458. 9. Ronchetti IP, Quaglino D, Bergamini G. Ascorbic Acid and Connective Tissue. Subcellular Biochemistry, Volume 25: Ascorbic Acid: Biochemistry and Biomedical Cell Biology. Plenum Press, New York, 1996. 10. Vilter RW. Nutritional aspects of ascorbic acid: uses and abuses. West J Med 1980;133:485492. 11. Stephens P and Thomas D. The Cellular Proliferate Phase of the Wound Repair Process, Journal of Wound Care 11:253-61, July 2002. 12. Pinchcofsky-Devin GD, Kaminski MV Jr. Correlation of pressure sores and nutritional status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:435-440.

13. Thomas DR. The role of nutrition in prevention and healing of pressure ulcers. Clin Geriatr Med. 1997;13:497-511. 14. Lyder C, Yu C, Stevenson D, Mangat R, Empleo-Frazier O, Emerling J, McKay J. Validating the Braden Scale for the prediction of pressure ulcer risk in blacks and Latino/Hispanic elders: a pilot study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1998;44(suppl3A):42S-49S. 15. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.State Operations Manual,Guidance to Surveyors for Long Term Care Facilities, Appendix PP. http:www.cms.hhs.gov/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/12_NHs.asp. Revision 26, September 1, 2008. Accessed September 30, 2008.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Health According To The Scriptures - Paul NisonDocument306 pagesHealth According To The Scriptures - Paul NisonJSonJudah100% (1)

- Gestational Diabetes Research PaperDocument16 pagesGestational Diabetes Research Paperapi-251486092No ratings yet

- Arc 2Document1 pageArc 2api-251486092No ratings yet

- Arc 1Document1 pageArc 1api-251486092No ratings yet

- Ug DPD Advising SheetDocument2 pagesUg DPD Advising Sheetapi-251486092No ratings yet

- Resume 2014 RevisedDocument1 pageResume 2014 Revisedapi-251486092No ratings yet

- Negative IonDocument2 pagesNegative IonDekzie Flores MimayNo ratings yet

- The Cardiovascular System ReviewDocument18 pagesThe Cardiovascular System ReviewDanisha Reeves100% (1)

- Emergency Nursing: By: Keverne Jhay P. ColasDocument61 pagesEmergency Nursing: By: Keverne Jhay P. ColasGaras AnnaBerniceNo ratings yet

- OMFC Application RequirementsDocument1 pageOMFC Application RequirementshakimNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Shock in Critical Care NursingDocument25 pagesNeurogenic Shock in Critical Care Nursingnaqib25100% (4)

- +2 BIO-ZOO-EM - Vol-1 (1-6 Lessons)Document36 pages+2 BIO-ZOO-EM - Vol-1 (1-6 Lessons)Asraf Mohammed Siraj100% (1)

- Datasheet Reagent SansureDocument3 pagesDatasheet Reagent Sansuredanang setiawanNo ratings yet

- Principles of Routine Exodontia 2Document55 pagesPrinciples of Routine Exodontia 2رضوان سهم الموايدNo ratings yet

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledDocument12 pagesIndividual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledTiffanny Diane Agbayani RuedasNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Wrestling PDFDocument542 pagesSpiritual Wrestling PDFJames CuasmayanNo ratings yet

- (Ebook PDF) Equine Ophthalmology 3Rd Edition by Brian C. GilgerDocument41 pages(Ebook PDF) Equine Ophthalmology 3Rd Edition by Brian C. Gilgerjessica.rohrbach136100% (47)

- Tet PGTRB Zoology Model Question Paper 2Document14 pagesTet PGTRB Zoology Model Question Paper 2Subbarayudu mamillaNo ratings yet

- Bionic EyeDocument6 pagesBionic EyeAsfia_Samreen_29630% (1)

- Diagnostic Value of Gastric Shake Test For Hyaline Membrane Disease in Preterm InfantDocument6 pagesDiagnostic Value of Gastric Shake Test For Hyaline Membrane Disease in Preterm InfantNovia KurniantiNo ratings yet

- Patient Education: Colic (Excessive Crying) in Infants (Beyond The Basics)Document15 pagesPatient Education: Colic (Excessive Crying) in Infants (Beyond The Basics)krh5fnjnprNo ratings yet

- Neuromuscular Blocking AgentsDocument89 pagesNeuromuscular Blocking Agentslorenzo08No ratings yet

- 10.1055s 0039 1688815 - CompressedDocument15 pages10.1055s 0039 1688815 - CompressedYolanda Gómez LópezNo ratings yet

- How Does Global Warming Affect Our Living?Document19 pagesHow Does Global Warming Affect Our Living?Minahil QaiserNo ratings yet

- Cotton Varieties HybridsDocument15 pagesCotton Varieties HybridsAjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Unique Point Japanese AcupunctureDocument12 pagesUnique Point Japanese Acupuncturepustinikki100% (4)

- 6 Months Creditors Aging Reports: PT Smart Glove Indonesia As of 30 Sept 2018Document26 pages6 Months Creditors Aging Reports: PT Smart Glove Indonesia As of 30 Sept 2018Wagimin SendjajaNo ratings yet

- Essay ModelDocument4 pagesEssay ModelEmma MalekNo ratings yet

- Return Permit For Resident Outside UAEDocument3 pagesReturn Permit For Resident Outside UAElloyd kampunga100% (1)

- MenopauseDocument21 pagesMenopauseDr K AmbareeshaNo ratings yet

- Python Ieee Projects 2021 - 22 JPDocument3 pagesPython Ieee Projects 2021 - 22 JPWebsoft Tech-HydNo ratings yet

- Parasite 1Document22 pagesParasite 1OnSolomonNo ratings yet

- Outlook Newspaper - 25 June 2009 - United States Army Garrison Vicenza - Caserma, Ederle, ItalyDocument8 pagesOutlook Newspaper - 25 June 2009 - United States Army Garrison Vicenza - Caserma, Ederle, ItalyUS Army AfricaNo ratings yet

- Atisara Krimi - 2018 BAMS DetailDocument12 pagesAtisara Krimi - 2018 BAMS DetailmasdfgNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and Offending: Area of Residence and The Impact of Social Disorganisation and UrbanicityDocument17 pagesSchizophrenia and Offending: Area of Residence and The Impact of Social Disorganisation and UrbanicityMustafa ŠuvalijaNo ratings yet