Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Idea and Iep

Uploaded by

api-2539846640 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views4 pagesOriginal Title

idea and iep

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views4 pagesIdea and Iep

Uploaded by

api-253984664Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

rently, the attitude towards

LRE is inclusion in the gen-

eral education classroom.

However, depending on the

child this will vary; if the

child will receive the best

overall education in a sepa-

rate environment, then this

new setting may be consid-

ered the LRE.

The Individuals with Dis-

abilities Education Act

(IDEA) was passed in 2004.

The purpose of this act is to

ensure a quality education for

all children with disabilities,

and to protect the rights of

these children and their fami-

lies. Some key points of

IDEA are free and appropri-

ate public educa-

tion (FAPE), Individualized

Education Plans (IEPs), and

the least restrictive environ-

ment (LRE). FAPE essen-

tially means that all students

with disabilities are provided

with the necessary accommo-

dations, such as special edu-

cation services, that enable

the child to receive an

appropriate education for

free. Appropriate in this

instance does not mean

best nor does it mean that it

will maximize the childs

potential. IEPs are required

by law, to ensure this appro-

priate education. The IEP is

a plan stating the childs

academic and social objec-

tives and goals, how to attain

them, and a description of the

childs strengths, weaknesses

and interests. LRE refers to

the optimal environment of

learning for the child. Cur-

IDEA: What is it?

Inside this

issue:

IDEA: An

Overview

1

Rights of the

Student and

Family

1

Schools

Obligations

2

IEP: An overview 2

The IEP 3

Assessing the IEP 3

IEP Referral

Process

3

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

Ryan Conklin VOLUME 1, ISSUE 1

Rights of the Student, Rights of the Parent

The student and the par-

ent also have very spe-

cific rights under IDEA.

For one, the student is

entitled to FAPE, an IEP,

and LRE. This also in-

cludes continued educa-

tion in the event that the

child is removed from

school for 10 or more

days, regardless of the

misconduct. Secondly,

the parent/guardian of

the child holds a great

deal of authority under

IDEA. If a student is to

be evaluated for special

education eligibility, the

parent must be informed.

If the parent agrees, then

the evaluation can take

place. However, if a

parent does not consent,

then the process cannot

continue. This is not

consent for special edu-

cation! In order for the

child to receive special

education services, the

parent must again pro-

vide consent. The parent

is also entitled to be an

active member of the IEP

team; while this is not

mandatory, it is highly

encouraged. If a change to

any existing evaluation,

placement or identification

is proposed, then the par-

ent must receive a written

notice thoroughly explain-

ing the change. Finally,

the parent has the right to

request a due process hear-

ing for any issues regard-

ing their childs education.

If the parent prevails, then

the school is liable for at-

torney expenses, and vice

versa.

LRE: Least Restrictive

Environment

FAPE: Free and

Appropriate Public

Education

IEP: Individualized

Education Plan

Page 2 INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES EDUCATION ACT

IDEA provides rights to the

parent, and also describes the

rights and obligation of the

school. In addition to providing

FAPE, LRE and IEPs, the

school must follow certain

evaluation protocol. First, the

school is required to identify,

and evaluate all students with

disabilities. Through their

evaluation, the school must use

a variety of assessment tools

and strategies to gather relevant

functional, developmental, and

academic information. IDEA

also states that schools must

implement early intervention

services that rely on proven

methods of teaching and learn-

ing, such as Response to Inter-

vention (RTI). The school dis-

trict must also provide the fac-

ulty and staff with appropriate

professional development ser-

vices so they can implement

these practices. After a student

has been identified and evalu-

ated, the school must reevaluate

a child at least once a year,

unless the parent and school

agree otherwise. IDEA man-

dates the school to hire and train

highly qualified personnel to

provide special education.

Lastly, the school is obligated to

reimburse the expenses for an

alternate education if they do not

meet FAPE in a timely manner,

as determined in court.

Obligations of the School

sometimes the principal, and the

parents. In some cases, the stu-

dent can also be a part of the

team. The team is rather cir-

cumstantial, and outside experts

may be included in the team

depending on the disability; but

typically the mention personnel

are the core team members.

While there is a legal time line

that the creation of an IEP must

follow, the process is designed

for quick implementation.

Lastly, the IEP is a legal docu-

ment, meaning the school is

accountable for following the

IEP. However, the school is not

legally liable for ensuring the

student meets all of his/her in-

tended goals and objectives.

Individualized Education Plan

An Individualized Education

Plan, or IEP, is a legal document

that is catered specifically to one

student. No two IEPs are the

same. In order to receive an

IEP, a student must meet certain

criteria; eligibility for special

education services, and a disabil-

ity that negatively affects the

students educational progress.

In other words, simply having a

disability does not grant an IEP.

The IEP is created by an IEP

Team. This team is typically

made up of the students imme-

diate teacher, a special educator,

a representative of the district,

RTI is a

systematic

approach to

assist children

who are having

difficulties

learning.

Page 3 VOLUME 1, ISSUE 1

The Referral Process

The referral process for an IEP can be complicated. When broken down, it can be

seen as a five step process. First, the student is pre-referred. What this means: A

teacher or parent may notice some abnormalities in their student/childs education and

decide to investigate. Typically, an intervention process will take place. Different

strategies will be implemented in class to try and remedy any learning issues. From

here, three options exist; the intervention works, the intervention sort of works, or the

intervention fails. If the intervention is successful, no further steps are required. If

the intervention sort of works, then different strategies may be tried out and evalu-

ated. If the interventions simply do not work, the student is referred, only if a parent

gives consent. This is step two, the referral and testing. Once referred, the school

will have 120 days to have a licensed psychiatrist test and evaluate the student to de-

termine any disability. If a disability is found, the process continues to step 3; deter-

mination of eligibility. At this step, the core team (now the parents, teacher, psy-

chiatrists) make a decision and recommendation for special education eligibility. If

eligibility is permitted, then the child can now receive special services. However, the

parents can deny consent at this point if they feel their child does not need special

education services. Assuming consent is given, we move to step 4; the IEP meeting.

The core team of educators and parents meet and create a unique IEP for the child and

decide on the least restrictive environment (LRE). Following, the IEP is implemented

and progress is recorded, which brings us to step 5; re-evaluation. By law, the school

must review the IEP every year and make suggestions for revisions and changes if

needed. Every 3 years the child must be re-evaluated in all aspects to determine pro-

gress and any core changes, which brings the cycle back to the testing step.

Assessing and Evaluating the IEP

The student and the IEP are regularly assessed to ensure all

potential measures have been taken to create the best pos-

sible learning experience for the child. It is worth noting

however, that good grades does not mean (IEP) progress.

Grades are an indicator of academic knowledge, but are far

too subjective to be used as a reliable determining factor of

an IEP. So, when evaluating the student and IEP, more

objective practices are implemented. This means content

and skill specific testing that results in objective scores

should be used to track the academic progress of the stu-

dent. Secondly, depending on the student, social goals

may be a part of the IEP. Again, this progress cannot

solely be based on the teachers opinion. Instead, social

goal and objective progress must be evaluated by multiple

people, including psychiatric professionals. The IEP re-

evaluation process should also include professionals, and

the entire team involved in the childs education. The

point of this re-evaluation is to make necessary changes to

the document so that a better education experience can be

provided. As a result, it is important that accurate records

of the child be kept at all times.

The Individualized Education Plan, more commonly known as

the IEP is in many ways the bread and butter of a student with

a disabilitys education. This document articulates absolutely

everything needed to ensure that the student has access to a

quality, and appropriate education. The IEP will include the

childs most pertinent information. This includes a detailed

description of the childs disability, strengths, learning styles,

interests and hobbies. Any piece of information that will aide

in the students instruction, learning, and even social abilities

is included. The IEP will articulate year-end goals that pertain

to the students unique set of needs, as well as objectives and

benchmarks to meet throughout the year. It is important that

everything on the IEP is written with great care; subjective

language is not helpful! Very specific terms that specify ex-

actly what is meant should be used. Lastly, the IEP will iden-

tify any additional resources the child needs to be successful.

This can be a wide range of things, as each childs needs will

differ. Common resources are often counseling time, one-on-

one time with an aide, different academic intervention ser-

vices, the use of specific technologies and so on. Basically,

any type of resource that the student needs to have an appro-

priate education will be described in the IEP, and provided.

The IEP

5 Steps

Pre-Referral 1

Test and Eval 2

Eligibility 3

IEP Meeting 4

Re-Evaluate 5

CHADD. (2013). About AD/HD. Retrieved October 29, 2013, from National Research Cener on ADHD: http://

www.help4adhd.org/en/about

LDA. (2013). For Teachers: Types of Learning Disabilities. Retrieved October 27, 2013, from Learning Disabilities

Association of America: http://www.ldaamerica.org/index.cfm

NCLD. (2013). Types of LD. Retrieved October 29, 2013, from National Center for Learning Disabilities: http://

www.ncld.org/types-learning-disabilities

NICHCY. (2013). Learning Disabilities (LD). Retrieved October 27, 2013, from National Dissemination Center for

Children with Disabilities: http://nichcy.org/disability/specific/ld

Reynolds, T., Zupanick, C. E., & Dombeck, M. (2013, May 21). Intellectual Disabilities. Retrieved October 27,

2013, from MentalHelp.net: http://www.mentalhelp.net/poc/view_doc.php?type=doc&id=10371&cn=208

Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (2013). Emotional Disturbance. Retrieved 10 28, 2013, from Education.com:

http://www.education.com/reference/article/emotional-disturbance/

WebMD. (2013). A Visual Guide to ADHD in Adults. Retrieved October 29, 2013, from WebMD: http://

www.webmd.com/add-adhd/ss/slideshow-adhd-in-adults

Wright, W. &. (2007). An Overview of IDEA 2004. In W. &. Wright, Special Education Law (pp. 19-36). New

York: Harbor House Law Press.

References

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Weekly Lesson Plans Spanish 1-2Document8 pagesWeekly Lesson Plans Spanish 1-2JaimeNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Wellness Wheel Assess & StepsDocument3 pagesWellness Wheel Assess & StepsSim KamundeNo ratings yet

- Midterm Examination in Statistics and Probability: For Numbers: 6 - 8, Given The TableDocument4 pagesMidterm Examination in Statistics and Probability: For Numbers: 6 - 8, Given The TableMissEu Ferrer MontericzNo ratings yet

- Conklin Resume 2016Document1 pageConklin Resume 2016api-253984664No ratings yet

- Action PlanDocument14 pagesAction Planapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Excel Spread Sheet FractionsDocument2 pagesExcel Spread Sheet Fractionsapi-253984664No ratings yet

- American Revolution TimelineDocument5 pagesAmerican Revolution Timelineapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Ches ChampDocument1 pageChes Champapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Teacher InquiryDocument2 pagesTeacher Inquiryapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Adjudicated Youth StudyDocument22 pagesAdjudicated Youth Studyapi-253984664No ratings yet

- NewslettersDocument5 pagesNewslettersapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Reading RecordDocument2 pagesReading Recordapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Analysis of Student WorkDocument6 pagesAnalysis of Student Workapi-253984664No ratings yet

- BJM DanceDocument2 pagesBJM Danceapi-253984664No ratings yet

- LD and AdhdDocument4 pagesLD and Adhdapi-253984664No ratings yet

- National Flowers Around The WorldDocument14 pagesNational Flowers Around The Worldapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Morning MeetingDocument1 pageMorning Meetingapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Aztec UnitDocument43 pagesAztec Unitapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Artifact Intro and Ed IdDocument4 pagesArtifact Intro and Ed Idapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Plants and Animals Lesson 3 ReflectionDocument3 pagesPlants and Animals Lesson 3 Reflectionapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Modified Re-Write PassageDocument2 pagesModified Re-Write Passageapi-253984664No ratings yet

- Educational TheoristsDocument1 pageEducational Theoristsapi-253984664No ratings yet

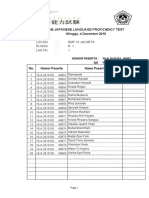

- Adoc - Pub - The Japanese Language Proficiency Test Minggu 4 deDocument24 pagesAdoc - Pub - The Japanese Language Proficiency Test Minggu 4 deSushi Ikan32No ratings yet

- Perceived Effects of Lack of Textbooks To Grade 12Document10 pagesPerceived Effects of Lack of Textbooks To Grade 12Jessabel Rosas BersabaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Submitted by Maryam Mumtaz Submitted To Mam Tyabba NoreenDocument3 pagesAssignment Submitted by Maryam Mumtaz Submitted To Mam Tyabba NoreenShamOo MaLikNo ratings yet

- TVVP0462985 Appointment LetterDocument1 pageTVVP0462985 Appointment Letterpreethidayal sarigommulaNo ratings yet

- System: Thi Nhu Ngoc Truong, Chuang WangDocument10 pagesSystem: Thi Nhu Ngoc Truong, Chuang Wangthienphuc1996No ratings yet

- University of Zambia: Physics Handbook 2009Document62 pagesUniversity of Zambia: Physics Handbook 2009Robin Red MsiskaNo ratings yet

- Exposure and Focus On Form Unit 10Document24 pagesExposure and Focus On Form Unit 10lilianabor100% (5)

- Music Staff and Treble Clef Lesson Plan Grade 4Document2 pagesMusic Staff and Treble Clef Lesson Plan Grade 4api-490791018No ratings yet

- THEME: Who Am I ?: Asia Pacific Rayon Toastmasters Club District 87 Division H Area 3Document1 pageTHEME: Who Am I ?: Asia Pacific Rayon Toastmasters Club District 87 Division H Area 3Aldo WijayaNo ratings yet

- Q2 M1 w1 2 Physical Education and Health 3Document19 pagesQ2 M1 w1 2 Physical Education and Health 3Andrea Klea ReuyanNo ratings yet

- INSTRUCTIONS Discussion Assignment InstructionsDocument2 pagesINSTRUCTIONS Discussion Assignment InstructionsMeriam AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Bamboo Paper Making: Ages: Total TimeDocument4 pagesBamboo Paper Making: Ages: Total TimeBramasta Come BackNo ratings yet

- Lessons and Activities On Apartheid DBQDocument25 pagesLessons and Activities On Apartheid DBQChaii Madlangsakay Tolentino100% (1)

- A Common Man Story - Inspiring Stories For KidsDocument2 pagesA Common Man Story - Inspiring Stories For KidsAkshay LalwaniNo ratings yet

- The Mystery of The Missing Footbal CupDocument10 pagesThe Mystery of The Missing Footbal CupJose LuisNo ratings yet

- 2nd Grade Journey's Unit 1 Week3 Day 1 Animal TraitsDocument49 pages2nd Grade Journey's Unit 1 Week3 Day 1 Animal TraitsDalia ElgamalNo ratings yet

- Scientific AttitudesDocument24 pagesScientific AttitudesMayleen Buenavista100% (1)

- Sloan Elizabeth CassarDocument1 pageSloan Elizabeth Cassarapi-519004272No ratings yet

- English For Lawyers I PDFDocument182 pagesEnglish For Lawyers I PDFDenise CruzNo ratings yet

- IIT BHU's E-Summit'22 BrochureDocument24 pagesIIT BHU's E-Summit'22 BrochurePiyush Maheshwari100% (2)

- Question: Given V 5x 3 y 2 Z and Epsilon 2.25 Epsilon - 0, ND (A) E at PDocument1 pageQuestion: Given V 5x 3 y 2 Z and Epsilon 2.25 Epsilon - 0, ND (A) E at Pvnb123No ratings yet

- MELC PlanDocument2 pagesMELC PlanAlfred BadoyNo ratings yet

- Ethnographic IDEODocument5 pagesEthnographic IDEORodrigo NajjarNo ratings yet

- Romania's Abandoned Children: Deprivation, Brain Development, and The Struggle For RecoveryDocument2 pagesRomania's Abandoned Children: Deprivation, Brain Development, and The Struggle For RecoveryEmsNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Computer Technology Timeline ProjectDocument2 pagesEvolution of Computer Technology Timeline Projectapi-309498815No ratings yet

- School & Society SecondaryModuleDocument156 pagesSchool & Society SecondaryModuletilayeyideg100% (8)