Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brown

Uploaded by

api-255084253Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brown

Uploaded by

api-255084253Copyright:

Available Formats

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal

of Gerontological Nursing

Page 1 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

Nursing

Journal of Gerontological Nursing

October 2013 - Volume 39 ! Issue 10: 34-43

DOI: 10.3928/00989134-20130612-02

FEATURE ARTICLE

Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction,

Turnover Rate, Assistant Education Program on and

Clinical Outcomes

Megan Brown, MPH; Roberta E. Redfern, PhD; Katrina Bressler, RN, CDP; Tamara May

Swicegood, RN; Marianne Molnar, RN, BSN, MBA

Abstract

Certified nursing assistants (CNAs) have become an integral part of the health care

system, spend the most amount of time with residents, and yet have the least amount of

training. Recent reports demonstrate that CNAs believe their salary is not commensurate

with their workload, and turnover rates in this field have indicated low job satisfaction. In

light of these issues, we developed an advanced training program for CNAs in our

institution to determine whether investing in our employees would increase job

satisfaction and therefore impact turnover rates and clinical outcomes. Although overall

job satisfaction improved slightly during the study period, satisfaction with training offered

was the only area significantly affected by the intervention; however, significant

decreases in turnover rates were observed between the pre- and postintervention

periods. Clinical indicators were slightly improved, and the number of resident urinary

tract infections decreased significantly. Offering an advanced training program for CNAs

may be an effective way to improve morale, turnover rates, and clinical outcomes.

[Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 39(10), 3443.]

Ms. Brown is Statistical Specialist and Dr. Redfern is Medical Science Writer, The Toledo

Hospital, Sponsored Research, Toledo; Ms. Bressler is Director of Nursing, ProMedica

Health System, The Goerlich Center; Ms. Swicegood is RN Case Manager, ProMedica

Caring Home Health Services; and Ms. Molnar is Director of Nursing, ProMedica Health

System, Sylvania, Ohio.

The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise. The

authors thank all of the staff who assisted in implementing the training course and data

collection process.

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 2 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

Address correspondence to Marianne Molnar, RN, BSN, MBA, Director of Nursing,

ProMedica Health System, Lake Park, 5100 Harroun Road, Sylvania, OH 43560; e-mail:

Marianne.molnar@promedica.org.

Received: September 17, 2012

Accepted: February 08, 2013

Posted Online: June 21, 2013

Certified nursing assistants (CNAs) have becomedue in part to economic strainsthe

employees in nursing homes who provide the greatest portion of care to residents, yet

they receive the least amount of education and training (Pennington, Scott, & Magilvy,

2003; Radcliffe, 1995; Russo & Lancaster, 1995). Mandatory CNA requirements have not

changed since being established more than 20 years ago and do not reflect the needs of

todays older and frailer residents (Sengupta, Harris-Kojetin, & Ejaz, 2010). CNAs in most

states must complete less than 2 weeks of training and then manage the daily lives of

medically complex, frail older adults, often with little guidance or support. Due to this shift

in caregiver roles and responsibilities, advanced educational programs have begun to be

developed and evaluated (Gursky & Ryser, 2007; Hancock & Campbell, 2006; Lerner,

Resnick, Galik, & Russ, 2010; Spencer, 2001), focusing on the educational process and

measuring the retention of knowledge and increases in competencies (Barczak & Spunt,

1999; Field & Smith, 2003). Although few studies have reported the effect of an

advanced educational program on clinical outcomes within their facilities, initial reports

are promising (Bonner, Castle, Men, & Handler, 2009; Bonner, MacCulloch, Gardner, &

Chase, 2007; Howe, 2008) and indicate that CNAs are enthusiastic about receiving more

training (Barczak & Spunt, 1999; Sengupta et al., 2010). Additionally, studies report that

CNAs express the desire for further education on a number of topics after completion of

an advanced educational program (Barczak & Spunt, 1999).

In comparison, relatively little research has been performed to assess the level of job

satisfaction of these CNAs. The high turnover rate of CNAs in nursing homes is

unsettling, especially considering that a recurrent theme in some interview research is

promising: I love what I do (Pennington et al., 2003). Various sources have cited annual

turnover rates of 45% to 400% and an estimated $4.1 billion in related costs (Harris-

Kojetin, Lipson, Fielding, Kiefer, & Stone, 2004; Pennington et al., 2003). Turnover of

CNAs is costly due to training of new personnel, but also disrupts the continuity and

quality of care (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2004). Reported job satisfaction has been linked to

this surprisingly high turnover rate and may be more dependent on the employees

environment and the facility than the work to be done (Arnetz & Hasson, 2007; Lapane &

Hughes, 2007; Pennington et al., 2003). Moreover, undesirable job behaviors and quality

of care have been found to be directly associated with job satisfaction (Arnetz & Hasson,

2007; Eaton, 2000; Irvine & Evans, 1995), making this an important area of focus for

administration.

Previous reports have suggested that CNAs enjoy the content of their work, but rate their

satisfaction with the rate of pay as poor (Castle, 2007). Additionally, because CNAs have

reported that their opportunity for advancement is low, the use of non-monetary rewards

has been suggested to improve this aspect of CNAs jobs. The creation of job ladders

and use of nurse mentors to foster communication have been advocated to improve job

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 3 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

satisfaction (Castle, 2007). It is also believed that investing in employees by offering

further education for CNAs may help improve job satisfaction and reduce turnover rates.

Such an educational program may provide a venue for communication to occur between

CNAs and administration, while improving CNAs knowledge and skills, which may be of

use in future efforts for job advancement.

Method

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this longitudinal cohort study, which

utilized pre- and postintervention surveys to assess the effects of an advanced training

program on CNAs job satisfaction. The study setting is a 203-bed facility located in

Sylvania, Ohio serving the long-term and post-acute skilled care needs of adults with an

average daily census of 197 patients. With five floors, care is provided for residents of

various acuity levels, including those who need specialty care services (e.g., hospice,

dementia care). The ground floor provides extensive rehabilitation services. Staffing

includes approximately 30 RNs, 55 licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and 150 CNAs, and

has been dedicated to serving the health care needs of the community for approximately

50 years.

Administration and staff development instructors designed an educational program for

the CNAs within our facility, based on Wolgins (2004) book, Being a Nursing Assistant.

The 3-day program was designed to provide advanced training to CNAs in a range of

topics, including basic content on anatomy and physiology, infection control, and aseptic

technique principles to enhance performance and compliance with competency and

quality standards. The course also aimed to discuss the CNAs role in the health care

environment, how each CNA may contribute to efficient team function, and foster

communication skills with other health care professionals. Staff were compensated for

attending the 3-day course, which included 2 classroom days in which teaching was

accomplished via interactive lectures, visual aids, and multimedia presentations.

Students attended five individual skills laboratories on Day 3 and were required to

demonstrate competency in each. CNAs completed a clinical competence assessment

pre-test prior to participation in the course; all employees took this examination again

upon completion and were required to achieve 80% to pass the course. This educational

program was designed and implemented as a mandatory requirement for all CNAs.

Those already employed at our facility were required to attend the course and all newly

hired CNAs were also required to complete the course, such that every CNA employed

by our facility has completed this advanced training. Training all employees took

approximately 16 weeks; the course continues to be a mandatory requirement of all

newly hired CNAs. CNA staff who demonstrated clinical and academic excellence during

the course received additional training to serve as mentors. The mentor program was

implemented to provide ongoing monitoring and preceptorship of the CNA staff.

The first class was offered in March 2011, at which point the Nursing Home Nurse Aide

Job Satisfaction Questionnaire (NHNA-JSQ, Castle, 2007) and Reciprocal Empowerment

Scale (RES, Klakovich, 1995), validated instruments developed specifically to measure

job satisfaction in CNAs, were distributed to all employees attending the course.

Employees were informed that a research study was being conducted, but were not told

that researchers planned to measure the effects of the advanced training course on their

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 4 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

reported levels of job satisfaction or any clinical indicators. Confidential envelopes were

provided to CNAs to collect surveys and return them to researchers anonymously. The

NHNA-JSQ was also distributed to all CNAs 6 months following the initial administration

of the instrument.

For this project, we retrospectively collected clinical data, which are continuously

maintained and reviewed by the facilitys leadership for quality purposes; this approach

was used for both the pre- and pos-tintervention periods. We compared the number of

patient falls, patient urinary tract infections (UTIs), patient decubitus ulcers, and

employee injuries for 6 months prior to the training program and for 6 months following

the last class to determine whether advanced training had an impact on clinical

outcomes. Additionally, employee turnover rates were recorded and compared to

determine the effect of this course on employee separation. We recorded the number of

CNA separations in the 6 months immediately prior to the course (September 2010

through February 2011, Period 1), as well as the year following the intervention (July

2011 until June 2012, Periods 2 and 3) to determine whether the course could have an

effect on turnover rates and how quickly that effect might be appreciated.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for demographic data. CNAs were asked to

complete the NHNA-JSQ and RES prior to participation in the educational/training

program and then again following the course. The individual scores, as well as domain

scores for each survey, were compared only for those individuals who completed both

surveys (N = 47) using t tests and Pearson correlation tests. Surveys of participants who

completed only the pre- or postintervention questionnaires were excluded for these

comparisons. Clinical outcome rates including those for acquired UTIs, skin

tears/bruises, pressure ulcers, and patient falls were compared using t tests. Employee

injury rates were also compared using t tests, whereas pair-wise comparisons of turnover

rates between pre- and postintervention periods were made using analysis of variance

(ANOVA) tests.

Results

Survey Results

During the study, 210 employees were eligible to participate; 132 CNAs completed the

preintervention survey. Of these, only 83 completed and returned the postintervention

survey; however, 36 were excluded due to incompleteness, such that 47 complete

surveys could be used for analysis. The overall response rate was 22.4%. CNAs at our

institution were primarily women (89.4%) (Table 1) and were mostly African American

(42.6%) or Caucasian (40.4%). Our sample was well distributed with respect to age

(Table 1); most had some college education, and the average amount of time employed

as a CNA was 10.7 years.

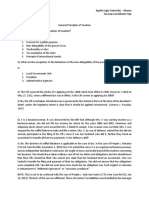

Table 1:

Study Population Demographics

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 5 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

Responses to the NHNA-JSQ were scored to report overall mean scores, mean scores

for each subscale, and mean scores for each response item for both the pre- and

postintervention surveys (Table 2). Each question is scored on a scale of 1 to 10, with

higher scores indicating a higher level of satisfaction. The results indicate that the CNAs

were least satisfied with the rewards associated with their position. The mean subscale

score for rewards was 6.37, whereas the mean score for rate how fairly you are paid

was 5.28 (SD = 2.68). No significant difference was noted in this subscale or either of its

items between the pre- and postintervention surveys (Table 2, p = 0.62).

Table 2:

NHNA-JSQ Responses

CNAs rated the quality of care the highest of all subscales, with a mean preintervention

score of 9.35. Neither this subscale nor its items scores changed significantly with the

intervention (p = 0.89) (Table 2). Furthermore, CNAs scored their work content highly;

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 6 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

this subscale was comprised of items such as Rate how much you enjoy working with

residents and Rate your closeness to residents and families. The mean score for this

subscale was 8.99 preintervention and did not change significantly after the educational

course (p = 0.83) (Table 2). Other subscales of the instrument, such as work demands,

workload, and coworkers, did not change significantly between the pre- and

postintervention administration of the survey (Table 2). However, the training subscale

changed significantly with the intervention (p = 0.003), as did two of the items within the

subscale: Rate whether your skills are adequate for the job (p = 0.05) and Rate the

training you have had to perform your job (p = 0.001) (Table 2). CNAs global rating of

their satisfaction with their job increased slightly between the pre- and postintervention

surveys, but was not significant (p = 0.80) (Table 2). Furthermore, the average score of

the entire survey increased slightly after the intervention, but was not significant.

Responses to the RES indicated slight increases in mean scores for all items (The RES

is scored on a scale of 1 to 5. All reported scores are means of the entire group.);

however, only the responses to My leader communicates clear, consistent expectations

were significantly different from initial responses following the intervention (p = 0.01)

(Table 3).

Table 3:

Reciprocal Empowerment Scale

Pre- and postintervention NHNA-JSQ and RES scores were compared among the CNAs

who responded to both surveys to determine whether age or number of years working as

a CNA affected satisfaction with any aspect of their job. CNAs who identified themselves

as being 41 or older reported significantly higher satisfaction than CNAs between ages

18 and 40 in four of the eight subscales of the pre-intervention NHNA-JSQ (Table 4);

older CNAs mean scores were significantly higher on 7 of the 22 items of the

questionnaire. Furthermore, older CNAs reported significantly higher global ratings of

their job satisfaction when compared to those in the 18-to-40 age group (Table 4). When

comparing the mean scores of the RES, older CNAs also tended to be significantly more

satisfied with their supervisor and indicated a greater level of pride from the work they

perform. Additionally, Pearson correlation tests of each item and subscale indicate that

the majority of the mean scores were positively correlated with age and number of years

working as a CNA, further suggesting that older CNAs are more satisfied with their jobs

(data not shown). The only subscales in which no differences were detected with respect

to age were the training, workload, and rewards subscales.

Table 4:

NHNA-JSQ Survey Results by CNA Age

The postintervention scores of CNAs were also compared as a function of age; although

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 7 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

the mean reported scores of the RES remained significantly different after the course, the

only significant difference in NHNA-JSQ scores that remained was in the work demand

subscale (Table 4).

Additionally, we compared the pre- and postintervention responses of each age group

separately; the only significant difference detected after completing the course in the

older group of CNAs was with regard to training. Alternately, the mean scores of the

CNAs who identified themselves as being age 18 to 40 improved in several areas,

including training, coworkers, and work demands. Younger CNAs agreed significantly

more that their leader communicates clear, concise expectations and uses their

recommendations after participating in the advanced training program after the

intervention (data not shown). Additionally, this group of CNAs reported an improved

global rating of their satisfaction; however, this improvement did not reach significance.

Overall, our results indicate that the younger CNAs job satisfaction was more strongly

affected by the advanced training program than was the satisfaction reported by CNAs

who were 41 and older. The satisfaction of older CNAs in our facility improved after the

training; however, this group reported a higher baseline satisfaction prior to the

intervention and continued to report higher levels of satisfaction than their younger

counterparts after the training. The intervention bridged many of the existing gaps

between the two groups and significantly improved CNAs rating of the training they

received to perform their jobs.

Turnover Rates

We observed the turnover rate of our CNAs in the 6-month period leading up to the

intervention to establish a baseline turnover rate. In the 6 months prior to the intervention,

the mean monthly turnover rate was 9.03% (SD = 1.38). Our educational program began

in March 2011, such that all existing employees would complete the course in June 2011.

We observed two consecutive time periods following the intervention to allow us to

compare and determine the programs effect on turnover rates. The first time period we

observed was the 6 months immediately following the intervention, in which the turnover

rate increased slightly, but not significantly, to 9.19% (SD = 4.18) (p = 0.99) (Table 5).

However, we continued to examine mean monthly turnover rates through May 2012,

allowing approximately 1 year to have elapsed since the last employee completed the

course. During the final time period, the mean monthly turnover rate decreased to 3.94%

(SD = 2.32), a significant decrease when compared to the preintervention period and 6-

month period immediately following the intervention (p = 0.03 for both time periods). The

overall change in turnover rate was also significant (p = 0.017) (Table 5).

Table 5:

ANOVA with Pair-Wise Comparisons

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 8 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical indicators of quality of care provided by our CNAs were chosen prior to initiation

of the research project, and CNAs were not made aware that these outcomes would be

tracked over time for research purposes. The number of patient acquired UTIs, skin tears

or bruises, falls, and acquired pressure ulcers were recorded during the 6-month periods

before and after the intervention. The average census for these periods was used to

estimate the proportions of residents affected, as the number of residents in the facility is

a dynamic variable. Chi-square analyses revealed that although the number of acquired

pressure ulcers and skin tears or bruises decreased after the intervention, neither was

significant (p = 0.62 and p = 0.33, respectively) (Table 6). However, the number of UTIs

occurring during the postintervention period was significantly lower than the rate of

acquired UTIs during the preintervention period (p < 0.001) (Table 6).

Table 6:

Chi-Square Analyses of the Effect of Advanced Nursing Assistant Training on

Relevant Clinical Outcomes

Discussion

CNA turnover rates continue to be a challenge for nursing home administration. The cost

effects of hiring and training new personnel are measurable, but more importantly, the

result is a disruption of continuity of care and subsequent decreased quality of care.

Moreover, as the aging population of our country continues to increase, the need for

caregivers in nursing homes will also continue to rise. The turnover rate of CNAs

becomes particularly troubling when one realizes that many CNAs who are leaving their

positions in nursing homes are leaving the health care work force entirely. Clearly,

without an improvement, there will soon be too few CNAs to care for nursing home

residents.

Our results echo those reported in previous studies; CNAs surveyed at our institution

indicated that their level of satisfaction with rewards for their efforts is lower than their

satisfaction with all other aspects of the job (Castle, 2007). Additionally, the highest level

of satisfaction reported by CNAs in our institution was in the quality of care they provide

to residents and the content of their work, a recurring theme in the literature. Of interest,

the results of our survey indicate that CNAs are well satisfied with nearly every domain.

Even the lowest scoring domain, rewards, received a neutral rating from employees.

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 9 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/n-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

Moreover, the scores for the other domains are higher than those reported previously in

the literature. Although this might indicate a higher level of satisfaction among CNAs in

our institution, it could also be a result of our small sample, due to low response rates.

Previous reports have included national surveys of large numbers of CNAs, who reported

much lower satisfaction globally and across all domains. Other studies including small

populations also reflected higher scores in job satisfaction (Lapane & Hughes, 2007;

Moyle, Skinner, Rowe, & Gork, 2003; Lerner, Resnick, Galik, & Flynn, 2011; Thompson,

Horne, & Huerta, 2011). Therefore, the level of satisfaction that our CNAs reported may

not reflect all CNAs job satisfaction.

Although our response rate was low, preventing generalization to all CNAs, it is important

to note that the scores of most subscales of the NHNA-JSQ either stayed nearly the

same or improved somewhat. The greatest improvement observed was in the training

subscale, in which the increase in mean score reached significance. This increase in

reported satisfaction with training indicates that our program was successful in helping

our CNAs to be more prepared and confident in their abilities to perform their job.

Additionally, the improvement in the mean scores in the RES indicate that the course

was an effective forum in which administration could communicate with CNAs, as their

rating of their leaders communication of expectations improved significantly. Whereas

other items rated did not reach significance, nearly all improved to some extent. Of

particular interest is the fact that older CNAs reported higher baseline job satisfaction

than their younger counterparts. However, many of the deficits appreciated prior to the

intervention were affected by the training, such that the global ratings of satisfaction were

no longer significant between age groups following the intervention. This suggests that

advanced training may be more effective in improving the job satisfaction of younger,

less experienced CNAs, while still beneficial to the group as a whole.

Moreover, the job turnover rate of CNAs in our facility improved significantly after the

educational intervention. We examined the 6-month period prior to the intervention to

establish a baseline turnover rate and began monitoring job turnover immediately

following the conclusion of the intervention to determine the amount of time necessary to

observe the interventions effect, if any. We did not observe an immediate effect of the

intervention on job turnover rate, as turnover rates peaked in the 3 months following the

completion of the course by all employees. However, rates began to fall 3 months

following the intervention and remained low at the time of writing. Additionally, it should

be noted that implementation of the advanced training course was mandatory for CNAs

facility-wide, such that every CNA was exposed to the intervention, regardless of whether

they decided to participate in the survey portion of the research project. Although it is not

possible to assert that the intervention and creation of a mentorship program are the

direct causes of the improved turnover rates, administration carefully controlled other

factors that might impact job satisfaction and turnover rates, such as incentives and

rewards commonly offered in our facilities (e.g., pizza parties) to better measure only the

effects of the educational program. Our results suggest that offering advanced training

and a CNA mentorship program positively affected job turnover rates.

Perhaps the most important result of this study is the impact of education on select

clinical outcomes. The number of skin tears or bruises decreased slightly in the 6-month

period following the intervention, as did the number of patient falls. The number of

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 10 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

acquired UTIs decreased significantly when comparing the 6-month periods before and

after the intervention, falling to less than half the rate of infection prior to the educational

course. This result suggests that the information provided regarding prevention of UTIs

was indeed successful. However, the rate of pressure ulcers increased slightly during the

study period. Although unexpected, this result allows administration to reexamine the

content of the material presented to the CNAs so that it may be adjusted to better

address this issue.

Several limitations of this study exist, most importantly, the low response rate. The

overall satisfaction scores as well as the subscale scores reported by the CNAs were all

high. When compared with national studies, which report much lower job satisfaction

rated by CNAs, it becomes a possibility that our study may suffer from bias due to

nonresponse. It is possible that only those CNAs who were satisfied with their position

overall were those who actually responded to the survey. Another limitation of our study

is the amount of time that passed between the administration of the educational course

and the time period in which clinical outcomes were observed. Although the course has

been ongoing since its introduction, only 2 months passed between the last existing

employee completing the course and the beginning of our clinical outcomes observation

period. It is possible that after longer observation periods, the effects of the

implementation of such an educational requirement may become more apparent in the

areas of job satisfaction, job turnover, and clinical outcomes.

Nursing Implications

The implications of our findings affect nurses, particularly those in administrative and staff

development roles. We have shown that development and implementation of a

homegrown training program for CNAs can improve their job satisfaction and affect

turnover rates of this staff. Furthermore, with advanced training, CNAs can positively

affect select clinical outcomes. Importantly, our research highlights the differences in

employee satisfaction as a function of age. We suggest that other institutions could

introduce a similar program to address specific clinical indicators while also improving

employee satisfaction and turnover rates. Finally, in-house development of a program of

this type allows for assessment of the effect on choice indicators, allowing administrators

and educators to target areas of weakness and adjust the program to suit their individual

needs.

Conclusion

Job satisfaction of CNAs may be linked to a number of variables of interest to health care

administrators, including quality of care and clinical outcomes. Satisfied employees are

less likely to leave an institution, thus investing in employees job satisfaction may help

retain existing employees and attract new ones, lowering costs and improving the

continuity and quality of care. Our results indicate that our CNAs are fairly satisfied with

their positions, but are least satisfied with the pay they receive. Furthermore,

respondents indicated a lower level of satisfaction with the amount of time they have to

perform their jobs, cooperation between coworkers, the amount of support they receive to

perform their jobs, and their chances to talk about concerns, suggesting other areas of

focus for leadership to improve employees job satisfaction. By offering a 3-day

educational course, we improved our CNAs satisfaction with the amount of training they

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 11 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

received and improved their confidence in their ability to care for residents. Responses to

the RES suggest that the course also served as a forum for communication between

leadership and CNAs. Furthermore, observed turnover rates decreased significantly after

the implementation of the educational course and the creation of a mentorship program

for CNAs. It is our belief that although CNAs are generally not satisfied with their

compensation, increased job satisfaction can be achieved by nonmonetary means.

Improved training and satisfaction may lead to employee retention and improved clinical

outcomes.

References

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 12 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

Arnetz, J.E. & Hasson, H. (2007). Evaluation of an educational toolbox for improving nursing staff competence and

psychosocial work environment in elderly care: Results of a prospective, non-randomized controlled intervention.

International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44, 723735. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.01.012 [CrossRef]

Barczak, N. & Spunt, D. (1999). Competency-based education: Maximize the performance of your unlicensed assistive

personnel. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 30, 254259.

Bonner, A., MacCulloch, P., Gardner, T. & Chase, C.W. (2007). A student-led demonstration project on fall prevention in a

long-term care facility. Geriatric Nursing, 28, 312318. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.04.014 [CrossRef]

Bonner, A.F., Castle, N.G., Men, A. & Handler, S.M. (2009). Certified nursing assistants perceptions of nursing home

patient safety culture: Is there a relationship to clinical outcomes?Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 10,

1120. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2008.06.004 [CrossRef]

Castle, N.G. (2007). Assessing job satisfaction of nurse aides in nursing homes: The Nursing Home Nurse Aide Job

Satisfaction Questionnaire. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 33(5), 4147.

Eaton, S.C. (2000). Beyond unloving care: Linking human resource management and patient care quality in nursing

homes. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 3, 591616. doi:10.1080/095851900339774 [CrossRef]

Field, L. & Smith, B. (2003). An essential care course for healthcare assistants. Nursing Standard, 17(44), 3335.

doi:10.7748/ns2003.07.17.44.39.c3418 [CrossRef]

Gursky, B.S. & Ryser, B.J. (2007). A training program for unlicensed assistive personnel. Journal of School Nursing, 23,

9297. doi:10.1177/10598405070230020601 [CrossRef]

Hancock, H. & Campbell, S. (2006). Developing the role of the healthcare assistant. Nursing Standard, 20(49), 3541.

doi:10.7748/ns2006.08.20.49.35.c4482 [CrossRef]

Harris-Kojetin, L., Lipson, D., Fielding, J., Kiefer, K. & Stone, R.I. (2004). Recent findings on frontline long-term care

workers: A research synthesis 19992003. Retrieved from http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/insight.htm

Howe, L. (2008). Education and empowerment of the nursing assistant: Validating their important role in skin care and

pressure ulcer prevention, and demonstrating productivity enhancement and cost savings. Advances in Skin & Wound

Care, 21, 275281. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000323505.45531.92 [CrossRef]

Irvine, D.M. & Evans, M.G. (1995). Job satisfaction and turnover among nurses: Integrating research findings across

studies. Nursing Research, 44, 246253. doi:10.1097/00006199-199507000-00010 [CrossRef]

Klakovich, M. (1995). Development and psychometric evaluation of the reciprocal empowerment scale. Journal of Nursing

Measurement, 3, 127143.

Lapane, K.L. & Hughes, C.M. (2007). Considering the employee point of view: Perceptions of job satisfaction and stress

among nursing staff in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 8, 813.

doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2006.05.010 [CrossRef]

Lerner, N.B., Resnick, B., Galik, E. & Flynn, L. (2011). Job satisfaction of nursing assistants. Journal of Nursing

Administration, 41, 473478. doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182346e7a [CrossRef]

Lerner, N.B., Resnick, B., Galik, E. & Russ, K.G. (2010). Advanced nursing assistant education program. Journal of

Continuing Education in Nursing, 41, 356362. doi:10.3928/00220124-20100401-10 [CrossRef]

Moyle, N., Skinner, J., Rowe, G. & Gork, C. (2003). Views of job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in Australian long-term

care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12, 168176. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00732.x [CrossRef]

Pennington, K., Scott, J. & Magilvy, K. (2003). The role of certified nursing assistants in nursing homes. Journal of Nursing

Administration, 33, 578584. doi:10.1097/00005110-200311000-00007 [CrossRef]

Radcliffe, I.K. (1995). Nursing assistive personnel in acute care. Framework for staff development. Journal of Nursing Staff

Development, 11, 189194.

Russo, J.M. & Lancaster, D.R. (1995). Evaluating unlicensed assistive personnel models. Asking the right questions,

collecting the right data. Journal of Nursing Administration, 25(9), 5157. doi:10.1097/00005110-199509000-00010

[CrossRef]

Sengupta, M., Harris-Kojetin, L.D. & Ejaz, F.K. (2010). A national overview of the training received by certified nursing

assistants working in U.S. nursing homes. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 31, 201219.

doi:10.1080/02701960.2010.503122 [CrossRef]

Spencer, H.A. (2001). Education, training, and use of unlicensed assistive personnel in critical care. Critical Care Nursing

Clinics of North America, 13, 105118.

Thompson, M.A., Horne, K.K. & Huerta, T.R. (2011). Reassessing nurse aide job satisfaction in a Texas nursing home.

Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 37(9), 4249. doi:10.3928/00989134-20110503-04 [CrossRef]

Wolgin, F. (2004). Being a nursing assistant (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

KEYPOINTS

Brown, M., Redfern, R.E., Bressler, K., Swicegood, T.M. & Molnar, M. (2013). Effects of

an Advanced Nursing Assistant Education Program on Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate,

and Clinical Outcomes. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 39(10), 3443.

Certified nursing assistants (CNAs) report a high degree of satisfaction with the work

they perform; however, those who were older or working as a CNA longer reported

significantly higher satisfaction.

6/28/14 3:46 PM Effects of an Advanced Nursing Job Satisfaction, Turnover Rate, Assistan Program on and Clinical Outcomes | Journal of Gerontological Nursing

Page 13 of 13 http://www.healio.com.hsl-ezproxy.ucdenver.edu/nursing/journals/jgn/-turnover-rate-assistant-education-program-on-and-clinical-outcomes

10.3928/00989134-20130612-02

A homegrown advanced training program significantly improved CNA-reported job

satisfaction and select clinical outcomes, as well as turnover rates.

The advanced training program had the greatest effect on the satisfaction scores of

the CNAs who were younger and reported fewer years of working as a CNA.

CNAs reported lowest overall satisfaction with their rate of pay; however, satisfaction

can be improved by nonmonetary means (e.g., advanced training and mentorship

programs).

You might also like

- Investigating CommitteeDocument2 pagesInvestigating CommitteeDenny Crane100% (1)

- Nursing Administration: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandNursing Administration: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Care Coordination: The Game Changer: The Game Changer How Nursing is Revolutionizing Quality CareFrom EverandCare Coordination: The Game Changer: The Game Changer How Nursing is Revolutionizing Quality CareNo ratings yet

- Continuing Education in Nursing - EditedDocument7 pagesContinuing Education in Nursing - EditedOnkwani DavidNo ratings yet

- Guide to Medical Education in the Teaching Hospital - 5th EditionFrom EverandGuide to Medical Education in the Teaching Hospital - 5th EditionNo ratings yet

- Oman Business GuideDocument17 pagesOman Business GuideZadok Adeleye50% (2)

- Improving Bedside Shift-To-shift Nursing Report ProcessDocument34 pagesImproving Bedside Shift-To-shift Nursing Report ProcessJaypee Fabros Edra100% (2)

- Abigail Harvey (Mcmahan) Galen College of Nursing BSN Program NSG 3100 Ms. Johnson March 25, 2021Document9 pagesAbigail Harvey (Mcmahan) Galen College of Nursing BSN Program NSG 3100 Ms. Johnson March 25, 2021api-581984607No ratings yet

- Nurse Residency Program 1Document5 pagesNurse Residency Program 1api-315956703No ratings yet

- Retail Management HandbookDocument43 pagesRetail Management HandbookMuzamil Ahsan100% (1)

- Compensation Methods For Architectural ServicesDocument7 pagesCompensation Methods For Architectural ServicesAbubakr Sidahmed0% (1)

- TransitionDocument13 pagesTransitionDonna NituraNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Practice-Nurses KnowledgeDocument82 pagesEvidence Based Practice-Nurses Knowledged-fbuser-63856902100% (2)

- Quality of Nursing Care Practices Among Select Hospitals in Bataan EditedDocument23 pagesQuality of Nursing Care Practices Among Select Hospitals in Bataan EditedZonllam Aryl DialorNo ratings yet

- Managing Attrition in The Indian Information Technology IndustryDocument5 pagesManaging Attrition in The Indian Information Technology IndustrybaladvNo ratings yet

- External Frame Factors - Hand-OutsDocument5 pagesExternal Frame Factors - Hand-OutsNegros Occidental Houses100% (2)

- Van Patten 2019Document6 pagesVan Patten 2019Amrinder RandhawaNo ratings yet

- Transition Within A Graduate Nurse Residency ProgramDocument10 pagesTransition Within A Graduate Nurse Residency ProgramkitsilNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument11 pages1 SMnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Nursing 1Document5 pagesNursing 1Ray NamuNo ratings yet

- Manuscript KHandyDocument23 pagesManuscript KHandySanjeev Sampang RaiNo ratings yet

- Advanced Practice NursingDocument11 pagesAdvanced Practice NursingSaher Kamal100% (2)

- Nurse Practitioners' Characteristics and Job Satisfaction: Sjsu ScholarworksDocument26 pagesNurse Practitioners' Characteristics and Job Satisfaction: Sjsu Scholarworkskaori mendozaNo ratings yet

- Issues in Nursing OrganizationsDocument6 pagesIssues in Nursing Organizationssebast107No ratings yet

- Structured Mentoring StrategiesDocument31 pagesStructured Mentoring Strategiesrandy gallegoNo ratings yet

- Nurse Managers' Responsive Coaching To Facilitate Staff Nurses' Clinical Skills Development in Public Tertiary HospitalDocument10 pagesNurse Managers' Responsive Coaching To Facilitate Staff Nurses' Clinical Skills Development in Public Tertiary Hospitalvan royeNo ratings yet

- Nurse Practitioner Job Satisfaction: Looking For Successful OutcomesDocument12 pagesNurse Practitioner Job Satisfaction: Looking For Successful OutcomesCorporacion H21No ratings yet

- Hypo FPX 4020 Assessment 3Document14 pagesHypo FPX 4020 Assessment 3Sheela malhiNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Impact of AcademicDocument15 pagesAssessing The Impact of AcademicSely AodinaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An IntegrativeDocument13 pagesNursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An Integrativecarlos treichelNo ratings yet

- Transition Shock, Preceptor Support and Nursing Competency Among NewlyDocument7 pagesTransition Shock, Preceptor Support and Nursing Competency Among NewlyNurfadhila IlhamNo ratings yet

- IRamirezNU310M2Credibility of SourcesDocument6 pagesIRamirezNU310M2Credibility of SourcesIvan RamirezNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Nurse Retention ProgramDocument53 pagesRunning Head: Nurse Retention Programcity9848835243 cyberNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Evaluating The Impact of Continuing Nursing Education September 2014Document10 pagesThe Importance of Evaluating The Impact of Continuing Nursing Education September 2014Jairus Joel A. SuminegNo ratings yet

- Nursing Doc - EditedDocument5 pagesNursing Doc - EditedMORRIS ANUNDANo ratings yet

- Human Resources For HealthDocument8 pagesHuman Resources For Healthdenie_rpNo ratings yet

- Dedicated EducationalDocument5 pagesDedicated EducationalNovin YetianiNo ratings yet

- Factors in Uencing The Performance of Reproductive Health Care Service Providers in BasrahDocument11 pagesFactors in Uencing The Performance of Reproductive Health Care Service Providers in BasrahRajaa A. MahmoudNo ratings yet

- New Graduate Nurse Preceptor Program: A Collaborative Approach With AcademiaDocument9 pagesNew Graduate Nurse Preceptor Program: A Collaborative Approach With AcademiaSunil MachambiNo ratings yet

- Article ContentDocument16 pagesArticle ContentindahNo ratings yet

- Running Head Nursing PreceptorshipDocument38 pagesRunning Head Nursing PreceptorshipdebbyNo ratings yet

- A Journey To Leadership: Designing A Nursing Leadership Development ProgramDocument7 pagesA Journey To Leadership: Designing A Nursing Leadership Development ProgramRindaBabaroNo ratings yet

- Influence of Emotional Intelligence, Communication, and Organizational Commitment On Nursing Productivity Among Korean NursesDocument8 pagesInfluence of Emotional Intelligence, Communication, and Organizational Commitment On Nursing Productivity Among Korean NursesSyifa AiniNo ratings yet

- Transformational and Transactional Leadership Styles of Nurse Managers and Job Satisfaction Among Filipino Nurses: A Pilot StudyDocument14 pagesTransformational and Transactional Leadership Styles of Nurse Managers and Job Satisfaction Among Filipino Nurses: A Pilot StudyDanyPhysicsNo ratings yet

- New Graduate Nurse Practice Readiness Perspectives On The Context Shaping Our Understanding and ExpectationsDocument5 pagesNew Graduate Nurse Practice Readiness Perspectives On The Context Shaping Our Understanding and ExpectationskitsilNo ratings yet

- Fitzpatrick OriginalDocument6 pagesFitzpatrick OriginalKristianus S PulongNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Trends in Nurse-MDocument10 pagesCurriculum Trends in Nurse-MmfhfhfNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Challenges and StrategiesDocument9 pagesReview Article: Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Challenges and StrategiesluNo ratings yet

- Statement of The ProblemDocument2 pagesStatement of The ProblemCHARLESNo ratings yet

- Professional Role Development PlanDocument7 pagesProfessional Role Development Planapi-532743877No ratings yet

- Orientation GuidelinesDocument24 pagesOrientation GuidelinesjitnunNo ratings yet

- 10 1111@jonm 13173Document26 pages10 1111@jonm 13173AbeerMaanNo ratings yet

- Clinical ReasoningDocument7 pagesClinical Reasoninglyndon_baker_10% (1)

- DescargaDocument8 pagesDescargaMonse SantillánNo ratings yet

- 2014 Eberhart DNP Final Project PDFDocument81 pages2014 Eberhart DNP Final Project PDFaya PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Artikel IlmiahDocument9 pagesArtikel IlmiahBayud Wae LahNo ratings yet

- Title Page: Title of The Article: "A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Programme OnDocument9 pagesTitle Page: Title of The Article: "A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Programme OnInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Resident Front Office ExperienceDocument5 pagesResident Front Office Experiencedelap05No ratings yet

- MC Cullagh 12 OHNfor 21 CenturyDocument11 pagesMC Cullagh 12 OHNfor 21 CenturyNurul FahmiNo ratings yet

- Journal of Global BiosciencesDocument25 pagesJournal of Global BiosciencesSamah IshtiehNo ratings yet

- Teaching Competency of Nursing Educators and Caring Attitude of Nursing StudentsDocument26 pagesTeaching Competency of Nursing Educators and Caring Attitude of Nursing StudentsJaine NicolleNo ratings yet

- FINAL Educational Goals in NursingDocument7 pagesFINAL Educational Goals in NursingJames FenskeyNo ratings yet

- Retaining Novice Nurses in A Healthcare OrganizationDocument8 pagesRetaining Novice Nurses in A Healthcare OrganizationRay NamuNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Health Literacy Scores and Patient Use of the iPET for Patient EducationFrom EverandRelationship Between Health Literacy Scores and Patient Use of the iPET for Patient EducationNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Mobile Medical SimulationFrom EverandComprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Mobile Medical SimulationPatricia K. CarstensNo ratings yet

- NeutrotoppppcDocument10 pagesNeutrotoppppcapi-255084253No ratings yet

- Cnaacuitytool 3Document1 pageCnaacuitytool 3api-255084253No ratings yet

- Pdca 2Document7 pagesPdca 2api-255084253No ratings yet

- Summary Email of April MeetingsDocument2 pagesSummary Email of April Meetingsapi-255084253No ratings yet

- Minutes From 3-14 MeetingDocument2 pagesMinutes From 3-14 Meetingapi-255084253No ratings yet

- Look Report Email Cnas 43014Document2 pagesLook Report Email Cnas 43014api-255084253No ratings yet

- Kayla Eval On MeDocument1 pageKayla Eval On Meapi-255084253No ratings yet

- Dixie RecDocument2 pagesDixie Recapi-255084253No ratings yet

- Revised Look Report 31114Document3 pagesRevised Look Report 31114api-255084253No ratings yet

- Asking For More CartsDocument1 pageAsking For More Cartsapi-255084253No ratings yet

- Tax Law LMT Aquila Legis FraternityDocument17 pagesTax Law LMT Aquila Legis FraternityWilbert ChongNo ratings yet

- Rob Leaverton Resume 2016 CertDocument7 pagesRob Leaverton Resume 2016 Certapi-342229926No ratings yet

- Rochelle ValleDocument4 pagesRochelle ValleDlanor NablagNo ratings yet

- Crew Handbook 2019 - Rev. 10.8.19Document69 pagesCrew Handbook 2019 - Rev. 10.8.19Sarah YNo ratings yet

- Payment of Bonus Rules (Pt.-4)Document9 pagesPayment of Bonus Rules (Pt.-4)Anonymous QyYvWj1No ratings yet

- Training Need AnalysisDocument83 pagesTraining Need Analysisneeraj00715925No ratings yet

- Quiz 564Document5 pagesQuiz 564Haris NoonNo ratings yet

- SkyHigh Liability WaiverDocument1 pageSkyHigh Liability WaiverZach HunterNo ratings yet

- Arco GulDocument65 pagesArco Gulharsh1100.hNo ratings yet

- Ra 9178Document11 pagesRa 9178Rahul HumpalNo ratings yet

- Socialist Fight No 15Document32 pagesSocialist Fight No 15Gerald J DowningNo ratings yet

- NSN Al-Saudia HR Policy - V2 0Document13 pagesNSN Al-Saudia HR Policy - V2 0Amr ElsheshtawyNo ratings yet

- Massive Online Open Course (MOOC) On Gender Sensitization: 20 May 2022 - July15 2022Document2 pagesMassive Online Open Course (MOOC) On Gender Sensitization: 20 May 2022 - July15 2022Sunil Kumar SalihundamNo ratings yet

- Croitoru Dragos ENGDocument3 pagesCroitoru Dragos ENGDragos CroitoruNo ratings yet

- Fuchs & Trottier (2013) - The Internet As Surveilled Workplayplace and FactoryDocument26 pagesFuchs & Trottier (2013) - The Internet As Surveilled Workplayplace and Factorybreadnroses100% (1)

- SPL Advt 52 1Document48 pagesSPL Advt 52 1Mithun DebNo ratings yet

- CS Form No. 34-C Plantilla of Casual Appointment - LGU RegulatedDocument1 pageCS Form No. 34-C Plantilla of Casual Appointment - LGU RegulatedBhabes Belen CreusNo ratings yet

- Coca - Cola Internship ReportDocument6 pagesCoca - Cola Internship ReportHasham NaveedNo ratings yet

- Annex A - OJT Internship Plan Culture and Arts Office and Cai, Carpio, Conty, & GuerreroDocument3 pagesAnnex A - OJT Internship Plan Culture and Arts Office and Cai, Carpio, Conty, & GuerreroGabriel M. GuerreroNo ratings yet

- EACI - Job Application FormDocument4 pagesEACI - Job Application FormMarianne CarantoNo ratings yet

- BSBMGT502 Student Assessment Task 1Document10 pagesBSBMGT502 Student Assessment Task 1Christine HoangNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter Examples MalaysiaDocument7 pagesCover Letter Examples Malaysiamhzkehajd100% (2)

- PRD JobsPikrDocument6 pagesPRD JobsPikrSaptadip SahaNo ratings yet

- CHUYÊN ĐỀ 3 - SỰ HÒA HỢP GIỮA CHỦ NGỮ VÀ ĐỘNG TỪDocument7 pagesCHUYÊN ĐỀ 3 - SỰ HÒA HỢP GIỮA CHỦ NGỮ VÀ ĐỘNG TỪTrân Hà100% (1)

- Himachal Pradesh Minimum Wages Notification 03/06/2014Document45 pagesHimachal Pradesh Minimum Wages Notification 03/06/2014Kapil Dev SaggiNo ratings yet