Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 159085, February 3, 2004

Uploaded by

maricar_rocaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 159085, February 3, 2004

Uploaded by

maricar_rocaCopyright:

Available Formats

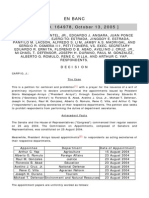

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

Case Name: Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 159085, February 3, 2004

Justice Stand

C.J. Davide, Jr. In the result

J. Carpio Concur

J. Corona Concur

J. Carpio-Morales Concur

J. Puno In the result

J. Vitug Separate opinion

J. Panganiban Separate opinion

J. Quisumbing Concurs with J. Panganiban

J. Ynares-Santiago Separate opinion

J. Sandoval-Gutierrez Dissent

J. Austria-Martinez Concur in the result

J. Callejo Concurs with J. Panganiban

J. Azcuna On official leave

What is the subject of the controversy?

Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4

What is the theme of this case?

Legal standing (Locus standi)

Mootness

Executive Powers

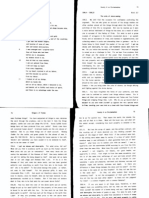

Facts:

- F1: On July 27, 2003, some three hundred junior officers and enlisted men

of the Armed Forces of the Philippines stormed into the Oakwood

Premiere apartments in Makati City demanding, among others, the

resignation of the President, the Secretary of Defense and the Chief of the

Philippine National Police.

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

- F2: In the wake of the Oakwood occupation, the President issued

Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4, both declaring a state of

rebellion and calling out the Armed Forces to suppress the rebellion.

- F3: By the evening of July 27, 2003, the Oakwood occupation had ended.

After hours-long negotiation, the soldiers agreed to return to barracks. The

President, however, did not immediately lift the declaration of a state of

rebellion and did only on August 1, 2003 through Proclamation No. 435

DECLARING THAT THE STATE OF REBELLION HAS CEASED TO EXIST.

- F4: This case is a consolidation of the cases (GR Nos. 159085, 159103,

159185, 159196) filed before the Court that challenge the validity of

Proclamation No. 427 and General order No. 4.

- Grounds relied upon by the petitioners:

o That Proclamation No. 427 and General order No. 4 are

unconstitutional:

Sanlakas and PM v. Executive Secretary, et al, G.R. No. 159085.

Section 18, Article VII of the Constitution does not require the

declaration of a state of rebellion to call out the armed forces.

There exists no sufficient factual basis for the proclamation by

the President of a state of rebellion for an indefinite period

because of the cessation of the Oakwood occupation.

SJS Officers/Members v. Hon. Executive Secretary, et al G.R. No.

159103.

Section 18, Article VII of the Constitution does not authorize

the declaration of a state of rebellion.

The declaration is a constitutional anomaly that confuses,

confounds and misleads because [o]verzealous public

officers, acting pursuant to such proclamation or general

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

order, are liable to violate the constitutional right of private

citizens.

The proclamation is a circumvention of the report requirement

under the same Section 18, Article VII, commanding the

President to submit a report to Congress within 48 hours from

the proclamation of martial law.

Presidential issuances cannot be construed as an exercise of

emergency powers as Congress has not delegated any such

power to the President.

Rep. Suplico et al. v. President Macapagal-Arroyo and Executive

Secretary Romulo, G.R. No. 159185

The declaration of a state of rebellion... amounts to a

usurpation of the power of Congress granted by Section 23 (2),

Article VI of the Constitution.

Pimentel v. Romulo, et al, G.R. No. 159196

The declaration of a state of rebellion opens the door to the

unconstitutional implementation of warrantless arrests for

the crime of rebellion (speculative)

- Grounds relied upon by the respondents:

o That Proclamation No. 427 and General order No. 4 are valid and

constitutional:

Executive Powers

Issue:

1. Do the petitioners have standing to file the instant petition?

2. Is the issue moot and academic?

3. Does the President have the power to declare a state of rebellion?

Ruling:

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

- R1: Only petitioners Rep. Suplico et al and Sen. Pimentel, as Members of

Congress, have standing to challenge the subject issuances. To the extent

the powers of Congress are impaired, so is the power of each member

thereof, since his office confers a right to participate in the exercise of the

powers of that institution (Philippine Constitution Association v. Enriquez).

On the other hand, petitioners, Sanlakas and PM, and SJS

Officers/Members, have no legal standing or locus standi to bring suit for

failure to demonstrate any injury to itself which would justify the resort to

the Court. Petitioner is a juridical person not subject to arrest. Thus, it

cannot claim to be threatened by a warrantless arrest. Nor is it alleged

that its leaders, members, and supporters are being threatened with

warrantless arrest and detention for the crime of rebellion. Every action

must be brought in the name of the party whose legal rights has been

invaded or infringed, or whose legal right is under imminent threat of

invasion or infringement (Lacson v. Perez). Even assuming that petitioners

are peoples organizations, this status would not vest them with the

requisite personality to question the validity of the presidential issuances.

That petitioner SJS officers/members are taxpayers and citizens does not

necessarily endow them with standing. A taxpayer may bring suit where

the act complained of directly involves the illegal disbursement of public

funds derived from taxation. No such illegal disbursement is alleged.

Moreover, a citizen will be allowed to raise a constitutional question only

when he can show that he has personally suffered some actual or

threatened injury as a result of the allegedly illegal conduct of the

government; the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged action; and the

injury is likely to be redressed by a favourable action. Again, no such injury

is alleged in this case. Furthermore, even granting these petitioners have

standing on the ground that the issues they raise are of transcendental

importance, the petitions must fail.

- R2: Petitions have been rendered moot by the lifting of the declaration. As

a rule, courts do not adjudicate moot cases, judicial power being limited to

the determination of actual controversies. Nevertheless, courts will

decide a question, otherwise moot, if it is capable of repetition yet

evading review. Hence, to prevent similar questions from reemerging, the

court has laid to rest the validity of the declaration of a state of rebellion in

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

the exercise of the Presidents calling out power, the mootness of the

petitions notwithstanding.

- R3: Yes. The President, as Commander-in-Chief, has a sequence of

graduated power[s]. From the most to the least benign, these are: the

calling out power, the power to suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas

corpus, and the power to declare martial law. In the exercise of the latter

two powers, the Constitution requires the concurrence of two conditions,

namely, an actual invasion or rebellion, and that public safety requires the

exercise of such power. These conditions are not required in the exercise of

the calling out power. The only criterion is that whenever it becomes

necessary, the President may call the armed forces to prevent or suppress

lawless violence, invasion or rebellion (Integrated Bar of the Philippines v.

Zamora). It is equally true that Section 18, Article VII does not expressly

prohibit the President from declaring a state of rebellion. Note that the

Constitution vests the President not only with Commander-in-Chief powers

but, first and foremost, with Executive powers. Moreover, from the U.S.

constitutional history, the Commander-in-Chief powers are broad enough

as it is and has become more so when taken together with the provision on

executive power and the presidential oath of office. Thus, the plenitude of

the powers of the presidency equips the occupant with the means to

address exigencies or threats which undermine the very existence of

government or the integrity of the State. In The Philippine Presidency A

Study of Executive Power, the late Mme. Justice Irene R. Cortes, proposed

that the Philippine President was vested with residual power and that this

is even greater than that of the U.S. President. She attributed this

distinction to the unitary and highly centralized nature of the Philippine

government. She noted that, There is no counterpart of the several states

of the American union which have reserved powers under the United

States constitution. Furthermore, the petitions do not cite a specific

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

instance where the President has attempted to or has exercised powers

beyond her powers as Chief Executive or as Commander-in-Chief. The

President, in declaring a state of rebellion and in calling out the armed

forces, was merely exercising a wedding of her Chief Executive and

Commander-in-Chief powers. These are purely executive powers, vested

on the President by Sections 1 and 18, Article VII, as opposed to

the delegated legislative powers contemplated by Section 23 (2), Article VI.

Salient Pronouncement(s):

The Presidents authority to declare a state of rebellion springs in the main from

her powers as chief executive and, at the same time, draws strength from her

Commander-in-Chief powers. [Section 4, Chapter 2 (Ordinance Power), Book III

(Office of the President) of the Revised Administrative Code of 1987.]

The mere declaration of a state of rebellion cannot diminish or violate

constitutionally protected rights. Indeed, if a state of martial law does not

suspend the operation of the Constitution or automatically suspend the privilege

of the writ of habeas corpus then it is with more reason that a simple declaration

of a state of rebellion could not bring about these conditions.

Source of Citations:

Philippine Jurisprudence and laws:

o

American Jurisprudence and laws:

o

Other secondary sources:

o

Analysis:

The court did not introduce a new doctrine or principle. It merely clarified

that declaring a state of rebellion is a purely executive power and not a

delegated legislative power.

Decided during Pres. Arroyos term.

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

Is the Courts ruling influenced by political factors?

No. The courts decision was not in any way influenced by political factors.

The decision was based on the extensive study and analysis of the nature

of the power to declare a state of rebellion and the scope of the Presidents

executive powers making reference to existing jurisprudence, academic

materials, and the history of the U.S. Constitution.

You might also like

- Case Digest - Pimentel v. ErmitaDocument1 pageCase Digest - Pimentel v. ErmitaJhonrey Lalaguna0% (1)

- G.R. No. 157509Document10 pagesG.R. No. 157509Klein CarloNo ratings yet

- Compiled01. Lopez Vs de Los Reyes (Bayle)Document15 pagesCompiled01. Lopez Vs de Los Reyes (Bayle)Mikhel BeltranNo ratings yet

- PACU Vs Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806 1955Document16 pagesPACU Vs Secretary of Education 97 Phil 806 1955DanielNo ratings yet

- IBP v. ZamoraDocument2 pagesIBP v. ZamoraJilliane OriaNo ratings yet

- CHREA v. CHRDocument2 pagesCHREA v. CHRML BanzonNo ratings yet

- 20.1 People vs. Gacott DigestDocument1 page20.1 People vs. Gacott DigestEstel TabumfamaNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law 1 - Prof. Alberto Muyot CASE DIGEST For F2021Document2 pagesConstitutional Law 1 - Prof. Alberto Muyot CASE DIGEST For F2021alfredNo ratings yet

- Tobias V AbalosDocument2 pagesTobias V AbalosMichelle DecedaNo ratings yet

- 09 IBP Vs ZAMORA G.R. No. 141284, August 15, 2000Document2 pages09 IBP Vs ZAMORA G.R. No. 141284, August 15, 2000Jezrael N. GrospeNo ratings yet

- Macias vs. ComelecDocument1 pageMacias vs. ComelecJP DC100% (1)

- Sarmiento Vs Mison DigestDocument2 pagesSarmiento Vs Mison DigestJohnelle Ashley Baldoza TorresNo ratings yet

- CONSTILAW1 - Digest Angara vs. Electoral CommissionDocument2 pagesCONSTILAW1 - Digest Angara vs. Electoral CommissionArthur Archie Tiu80% (15)

- Lacson Vs Perez Case DigestDocument1 pageLacson Vs Perez Case DigestFeBrluadoNo ratings yet

- g35 Qualifications David v. Poe-LlamanzaresDocument5 pagesg35 Qualifications David v. Poe-LlamanzaresDEAN JASPERNo ratings yet

- 16) Tolentino Vs Comelec 41 Scra 702Document2 pages16) Tolentino Vs Comelec 41 Scra 702Jovelan V. Escaño100% (3)

- De Castro V JBCDocument24 pagesDe Castro V JBCEgay EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Bolos vs. BolosDocument10 pagesBolos vs. BolosDexter CircaNo ratings yet

- Tichangco V EnriquezDocument1 pageTichangco V EnriquezGayeGabriel100% (1)

- Trillanes V PimentelDocument3 pagesTrillanes V PimentelAndré Braga100% (1)

- Dialdas VDocument6 pagesDialdas VAleah LS KimNo ratings yet

- CONSTI 1 Case Digest Demetria v. Alba, 148 SCRA 208 (1987) TOPIC: Separation of PowersDocument3 pagesCONSTI 1 Case Digest Demetria v. Alba, 148 SCRA 208 (1987) TOPIC: Separation of PowersFidela MaglayaNo ratings yet

- Consti - Arroyo Vs de Venecia 277 SCRA 258 (1997)Document17 pagesConsti - Arroyo Vs de Venecia 277 SCRA 258 (1997)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- CSC vs. CortesDocument3 pagesCSC vs. CortesJoel G. AyonNo ratings yet

- Arceta V MangrobangDocument3 pagesArceta V MangrobangxperiakiraNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-17144 Osmena Jr. vs. PendatunDocument4 pagesG.R. No. L-17144 Osmena Jr. vs. PendatunRaymondNo ratings yet

- 57 Scra 163 Oliveros VS VillaluzDocument2 pages57 Scra 163 Oliveros VS VillaluzJun RinonNo ratings yet

- Sanlakas v. Executive SecretaryDocument1 pageSanlakas v. Executive SecretaryOswald ImbatNo ratings yet

- Javellana v. Executive Secretary Case DigestDocument5 pagesJavellana v. Executive Secretary Case DigestCharmaine Grace100% (1)

- CASE DIGEST Arroyo vs. de VeneciaDocument2 pagesCASE DIGEST Arroyo vs. de VeneciaMiley LangNo ratings yet

- PNP Director Dela Paz Vs Senate Committee On Foreign Relations G.R. No. 184849 February 13, 2009 Nachura, J.Document2 pagesPNP Director Dela Paz Vs Senate Committee On Foreign Relations G.R. No. 184849 February 13, 2009 Nachura, J.Nicole LlamasNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 103524, April 15, 1992: Bengzon vs. DrilonDocument1 pageG.R. No. 103524, April 15, 1992: Bengzon vs. DrilonCheryl Fenol100% (1)

- Go Tek Vs Deportation BoardDocument3 pagesGo Tek Vs Deportation Boardlovekimsohyun89No ratings yet

- Consti Francisco Vs House of Representatives, 415 SCRA 44, GR 160261 (Nov. 10, 2003)Document3 pagesConsti Francisco Vs House of Representatives, 415 SCRA 44, GR 160261 (Nov. 10, 2003)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- Bondoc v. Pineda-DigestDocument1 pageBondoc v. Pineda-DigestJilliane OriaNo ratings yet

- Pacu Vs Secretary of Education Digest and Full TextDocument10 pagesPacu Vs Secretary of Education Digest and Full TextKing BautistaNo ratings yet

- Bengzon v. Drilon G.R. 103524, April 15, 1992Document2 pagesBengzon v. Drilon G.R. 103524, April 15, 1992TrinNo ratings yet

- Digest Ramon Gonzales Vs COMELECDocument1 pageDigest Ramon Gonzales Vs COMELECAlmer TinapayNo ratings yet

- Planas Vs ComelecDocument1 pagePlanas Vs ComelecEvangelyn Egusquiza100% (2)

- G.R. No. L-34150 Tolentino V ComelecDocument2 pagesG.R. No. L-34150 Tolentino V ComelecRia N. HipolitoNo ratings yet

- 7C-17 KMU Labor Center v. Garcia GR 115381 Dec. 23, 1994Document19 pages7C-17 KMU Labor Center v. Garcia GR 115381 Dec. 23, 1994arctikmarkNo ratings yet

- Angara vs. Electoral Commission 63 Phil. 139 (1936) Case DigestDocument1 pageAngara vs. Electoral Commission 63 Phil. 139 (1936) Case DigestAce Lawrence AntazoNo ratings yet

- 22 Integrated Bar of The Philippines v. Zamora (B2016)Document4 pages22 Integrated Bar of The Philippines v. Zamora (B2016)Monica MoranteNo ratings yet

- 01 Consti 1 Case DigestJ.M. Tuason Co. Inc. v. LTA G.R. No. L-21064 February 18 1970 RevisedDocument1 page01 Consti 1 Case DigestJ.M. Tuason Co. Inc. v. LTA G.R. No. L-21064 February 18 1970 RevisedChristian AribasNo ratings yet

- Gudani v. Senga, Case DigestDocument2 pagesGudani v. Senga, Case DigestChristian100% (1)

- Sandoval V Hret DigestDocument2 pagesSandoval V Hret DigestJermone Muarip100% (3)

- Manalo vs. SistozaDocument2 pagesManalo vs. SistozaCzarPaguioNo ratings yet

- Guingona vs. Carague Case DigestDocument2 pagesGuingona vs. Carague Case Digestbern_alt100% (4)

- Arceta V Mangrobang GR 152895Document6 pagesArceta V Mangrobang GR 152895Dorothy PuguonNo ratings yet

- People Vs PilotinDocument1 pagePeople Vs PilotinJam ZaldivarNo ratings yet

- En Banc (G.R. NO. 164978, October 13, 2005) : Carpio, J.: The CaseDocument8 pagesEn Banc (G.R. NO. 164978, October 13, 2005) : Carpio, J.: The CaseTin SagmonNo ratings yet

- Dimaporo Vs Mitra DigestDocument3 pagesDimaporo Vs Mitra Digestpawchan02No ratings yet

- 7C-13 Sanlakas Vs Executive Secretary G.R. No. 159085 February 3, 2004Document1 page7C-13 Sanlakas Vs Executive Secretary G.R. No. 159085 February 3, 2004sarahsheenNo ratings yet

- Javellana VS Executive SecretaryDocument5 pagesJavellana VS Executive SecretaryMA. TERESA DADIVASNo ratings yet

- Gonzales Vs ComelecDocument15 pagesGonzales Vs Comelecmichael actubNo ratings yet

- Noblejas v. TeehankeeDocument3 pagesNoblejas v. TeehankeeKang MinheeNo ratings yet

- 16 - in The Matter of Save The Supreme CourtDocument2 pages16 - in The Matter of Save The Supreme CourtNice RaptorNo ratings yet

- Case #1: The Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4 Are UnconstitutionalDocument93 pagesCase #1: The Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4 Are UnconstitutionalJayco-Joni CruzNo ratings yet

- Sanlakas v. Angelo Reyes (G.R. No. 159085)Document3 pagesSanlakas v. Angelo Reyes (G.R. No. 159085)Candelaria QuezonNo ratings yet

- Consti CasesDocument5 pagesConsti CasesJeje MedidasNo ratings yet

- SailorDocument1 pageSailormaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Litany Mary01 PDFDocument1 pageLitany Mary01 PDFmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Business Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesBusiness Plan Templatemaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Divine Mercy BrochureDocument2 pagesDivine Mercy Brochuremaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Day's Hotel Manage Breakfast ChoicesDocument2 pagesDay's Hotel Manage Breakfast Choicesmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Board of Environmental Planning-SyllabusDocument4 pagesBoard of Environmental Planning-SyllabusChristian SantamariaNo ratings yet

- Special Penal LawsDocument7 pagesSpecial Penal Lawsmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Bersamin Political Law Case Digests Compiled 2017 - Ateneo Law SchoolDocument31 pagesBersamin Political Law Case Digests Compiled 2017 - Ateneo Law Schoolmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- LetterDocument2 pagesLettermaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Bersamin Political Law Case Digests Compiled 2017 - Ateneo Law SchoolDocument31 pagesBersamin Political Law Case Digests Compiled 2017 - Ateneo Law Schoolmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Pointers in Mercantile Law 2017Document30 pagesPointers in Mercantile Law 2017maricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Income TaxationDocument4 pagesIncome Taxationmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- CASE STUDY in Civil ProcedureDocument2 pagesCASE STUDY in Civil Proceduremaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Tax CasesDocument14 pagesTax Casesmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Villafuerte v. RobredoDocument1 pageVillafuerte v. Robredomaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- BATCH 1 Division Cases (Bersamin)Document5 pagesBATCH 1 Division Cases (Bersamin)maricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Bersamin CasesDocument6 pagesBersamin Casesmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank vs. Aznar 649 SCRA 214 Facts: in 1958, RISCO Ceased Operation Due To Business Reverses. With The DesireDocument2 pagesPhilippine National Bank vs. Aznar 649 SCRA 214 Facts: in 1958, RISCO Ceased Operation Due To Business Reverses. With The Desiremaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Civil DigestsDocument2 pagesCivil Digestsmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Villafuerte v. RobredoDocument1 pageVillafuerte v. Robredomaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Grace Poe Vs COMELEC Digest 1Document3 pagesGrace Poe Vs COMELEC Digest 1Onireblabas Yor OsicranNo ratings yet

- Notes On Sales (Finals)Document15 pagesNotes On Sales (Finals)maricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law NotesDocument13 pagesTransportation Law Notesmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Bersamin CasesDocument6 pagesBersamin Casesmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank vs. Aznar 649 SCRA 214 Facts: in 1958, RISCO Ceased Operation Due To Business Reverses. With The DesireDocument2 pagesPhilippine National Bank vs. Aznar 649 SCRA 214 Facts: in 1958, RISCO Ceased Operation Due To Business Reverses. With The Desiremaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- MARINA v. COADocument1 pageMARINA v. COAmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Income TaxationDocument4 pagesIncome Taxationmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Comparative SummaryDocument12 pagesComparative Summarymaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Taboada v. Rosal (Torts - Fulltext)Document3 pagesTaboada v. Rosal (Torts - Fulltext)maricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- SU - JD CurriculumDocument1 pageSU - JD Curriculummaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- PDS - PinayDocument4 pagesPDS - PinayFridilyn AlconesNo ratings yet

- State of N.H. vs. Michael AddisonDocument263 pagesState of N.H. vs. Michael AddisonNew Hampshire Public RadioNo ratings yet

- Anand Behra Case FishDocument1 pageAnand Behra Case FishNitesh BhattNo ratings yet

- LectureDocument39 pagesLecturedaboy15No ratings yet

- A Private War 3 - Homeward BoundDocument110 pagesA Private War 3 - Homeward BoundTyCaine100% (3)

- Mahouka Koukou No Rettousei Volume 2Document109 pagesMahouka Koukou No Rettousei Volume 2Alyan Banulyan100% (2)

- Appointment of Clerks in Field Cadre Order No. 3272-3378 Dated 21.03.2018Document5 pagesAppointment of Clerks in Field Cadre Order No. 3272-3378 Dated 21.03.2018MANOJNo ratings yet

- Consunji vs. EsguerraDocument4 pagesConsunji vs. EsguerraYong Naz100% (1)

- End Violence Against WomenDocument2 pagesEnd Violence Against WomenunicefmadaNo ratings yet

- 32 All Latin Maxim SummaryDocument32 pages32 All Latin Maxim SummaryEkram AhmedNo ratings yet

- International Efforts To Combat Corruption: Prof. Dr. Mark PiethDocument18 pagesInternational Efforts To Combat Corruption: Prof. Dr. Mark PiethsemarangNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Province of Laguna Barangay - Office of The Barangay CaptainDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Province of Laguna Barangay - Office of The Barangay CaptainNehru Valdenarro ValeraNo ratings yet

- Capri Ristorante Fire Lane and Valet ServiceDocument3 pagesCapri Ristorante Fire Lane and Valet ServiceDavid GiulianiNo ratings yet

- PIL Case DigestsDocument19 pagesPIL Case DigestsJoycelyn Adato AmazonaNo ratings yet

- Prime WebAccess ManualDocument37 pagesPrime WebAccess ManualOae Florin0% (1)

- Fraud Risk Management GuideDocument2 pagesFraud Risk Management GuideClaudia LauraNo ratings yet

- 2-Legislation and Regulatory Compliance Register - Telstra Global PDFDocument1 page2-Legislation and Regulatory Compliance Register - Telstra Global PDFiraNo ratings yet

- 2016 2a Caetano V Massachusetts 14-10078 - AplcDocument12 pages2016 2a Caetano V Massachusetts 14-10078 - Aplcsilverbull8No ratings yet

- Narco SubmarinesDocument164 pagesNarco SubmarinesJUAN RAMON100% (3)

- Help The Denver Post and Crime StoppersDocument1 pageHelp The Denver Post and Crime Stoppersapi-26046374No ratings yet

- Https Campus - TcsDocument5 pagesHttps Campus - TcsAvi NashNo ratings yet

- Manuel Figueroa v. The People of Puerto Rico, 232 F.2d 615, 1st Cir. (1956)Document8 pagesManuel Figueroa v. The People of Puerto Rico, 232 F.2d 615, 1st Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Law and Emerging Technology PsdaDocument10 pagesLaw and Emerging Technology PsdaManan GuptaNo ratings yet

- Minimum Wages ActDocument52 pagesMinimum Wages Actanilkanwar111No ratings yet

- Bautista Vs Auto Plus TradersDocument1 pageBautista Vs Auto Plus TradersMary Joyce Lacambra AquinoNo ratings yet

- All Things Are The Slaves of The Power That Transcends All (PsDocument7 pagesAll Things Are The Slaves of The Power That Transcends All (Psdwutley100% (1)

- Access To Justice For Marginalised People in IndiaDocument17 pagesAccess To Justice For Marginalised People in IndiaAditya Prakash VermaNo ratings yet

- Ongkiko v. Court of Appeals, 154 SCRA 186Document1 pageOngkiko v. Court of Appeals, 154 SCRA 186G SNo ratings yet

- US vs. ExaltacionDocument2 pagesUS vs. ExaltacionattymaryjoyordanezaNo ratings yet

- Project On Criminal ConspiracyDocument17 pagesProject On Criminal ConspiracyShubhankar ThakurNo ratings yet