Professional Documents

Culture Documents

WSJ Article 2

Uploaded by

api-2349892440 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

289 views4 pagesOriginal Title

wsj article 2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

289 views4 pagesWSJ Article 2

Uploaded by

api-234989244Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

OPINION

How the U.S. Made the Ebola Crisis

Worse

The total number of Liberian doctors in America is about two-thirds the

total now working in their homeland.

By

E. FULLER TORREY

Oct. 14, 2014 7:19 p.m. ET

Amid discussions of quarantines, lockdowns and doomsday death scenarios about Ebola, little

has been said about the exodus of Africas health-care professionals and how it has contributed

to the outbreak. For 50 years, the U.S. and other Western nations have admitted health

professionalsespecially doctors and nursesfrom poor countries, including Liberia, Sierra

Leone and Guinea, three nations at the heart of the Ebola epidemic.

The loss of these men and women is now reflected in reports about severe medical-manpower

shortages in these countries, an absence of local medical leadership so critical for responding to

the crisis, and a collapse or near-collapse of their health-care systems.

Although Africa bears 24% of the global disease burden, it is home to just 3% of the worlds

health workforce. A 2010 World Health Organization assessment of doctors, nurses and

midwives per population listed Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea in the bottom nine nations in

the world in medical manpower.

ENLARGE

CORBIS

In Liberia, a nation of four million people, the number of Ebola cases is said to be doubling

every 15-20 days. Based on news reports, Ive estimated that there were about 120 Liberian

physicians in the country prior to the outbreak.

According to an American Medical Association database, in 2010 there were 56 Liberian-trained

physicians practicing in the U.S. This number does not include other Liberian physicians who

emigrated to this country, were unable to pass state licensing exams, and are employed as

technicians, administrators, or in other jobs. Older studies suggest that the number failing such

exams is about half of those licensed.

Thus the total number of Liberian physicians in the U.S. is probably about two-thirds the number

in Liberia. In addition, Liberian-trained physicians live in Canada, Great Britain and Australia.

The Liberian situation is not exceptional. Altogether in 2010 the U.S. had 265,851 licensed

physicians trained in other countries, constituting 32% of our physician workforce, according to

the AMA. Among these, 128,729 came from countries categorized by the World Bank as being

from low- or lower-middle income countries. These physicians tend to work disproportionately

in rural and inner-city jobs less favored by American medical graduates. West Virginia, for

example, has the highest proportion of foreign-trained physicians from poorer countries to U.S.-

trained physicians.

The U.S. has always welcomed health professionals from other countries. However in 1965,

responding to a perceived shortage of physicians for the growing U.S. population, Congress

passed landmark immigration legislation giving preference to health professionals. Subsequent

legislation in 1968, 1970 and 1994 further opened the door, especially for physicians from poorer

countries. The percentage of foreign-trained physicians has steadily increased from 10% of the

workforce in 1965 to its current 32%.

Many objections to this policy have been raised over the years. In 1967 Walter Mondale, then a

senator from Minnesota, called it a disgrace. It was inexcusable, he wrote in the Saturday

Review, that the U.S. should need doctors from countries where thousands die daily of disease

to relieve our shortage of medical manpower.

A 1974 report on the Brain Drain for the House Foreign Affairs Committee noted that the

current policy was widening the gap between rich and poor nations, and warned that the policy

has a great potential for mischief in the Nations future relations with the LDC [less developed

countries].

Despite such complaints, U.S. policy has continued to encourage the immigration of physicians

and other health workers from poorer countries. Theres nothing wrong with a foreign-trained

doctor, Casper Weinberger, then secretary of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare,

said on TV in 1973. Of course were using a lot of them, and will use a lot more.

The consequences of this policy may be more than mischief. Ebola may be merely the first of

many prices to be paid for our long-standing but shortsighted health manpower policy. Surely the

wealthiest country in the world should be able to produce sufficient health workers for its own

needs and not take them from the poorest countries.

Dr. Torrey is associate director of the Stanley Medical Research Institute and author of

American Psychosis: How the Federal Government Destroyed the Mental Illness Treatment

System (Oxford, 2013).

You might also like

- Insourced: How Importing Jobs Impacts the Healthcare Crisis Here and AbroadFrom EverandInsourced: How Importing Jobs Impacts the Healthcare Crisis Here and AbroadNo ratings yet

- The Ebola Survival Handbook: An MD Tells You What You Need to Know Now to Stay SafeFrom EverandThe Ebola Survival Handbook: An MD Tells You What You Need to Know Now to Stay SafeNo ratings yet

- Taking Care of Our Folks: A Manual for Family Members Caring for the Black ElderlyFrom EverandTaking Care of Our Folks: A Manual for Family Members Caring for the Black ElderlyNo ratings yet

- Health Care Disparity in the United States of AmericaFrom EverandHealth Care Disparity in the United States of AmericaRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Strategies for Awareness & Prevention of Hiv/Aids Among African-Americans: A Hand BookFrom EverandStrategies for Awareness & Prevention of Hiv/Aids Among African-Americans: A Hand BookNo ratings yet

- Under the Skin: racism, inequality, and the health of a nationFrom EverandUnder the Skin: racism, inequality, and the health of a nationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Misunderstanding Addiction: Overcoming Myth, Mysticism, and Misdirection in the Addictions Treatment IndustryFrom EverandMisunderstanding Addiction: Overcoming Myth, Mysticism, and Misdirection in the Addictions Treatment IndustryNo ratings yet

- Chronically American: Our Evolution Towards Chronic Illness and Our Radical Way ForwardFrom EverandChronically American: Our Evolution Towards Chronic Illness and Our Radical Way ForwardNo ratings yet

- 2050: Projections of Health for a Diverse Society; Individual Responsibility for the State of the Nation's HealthFrom Everand2050: Projections of Health for a Diverse Society; Individual Responsibility for the State of the Nation's HealthNo ratings yet

- Reclaiming Our Health: A Guide to African American WellnessFrom EverandReclaiming Our Health: A Guide to African American WellnessNo ratings yet

- What Your Doctor Won't Tell You: The Real Reasons You Don't Feel Good and What YOU Can Do About ItFrom EverandWhat Your Doctor Won't Tell You: The Real Reasons You Don't Feel Good and What YOU Can Do About ItNo ratings yet

- Living in the Shadow of Blackness as a Black Physician and Healthcare Disparity in the United States of AmericaFrom EverandLiving in the Shadow of Blackness as a Black Physician and Healthcare Disparity in the United States of AmericaNo ratings yet

- Migrants Who Care: West Africans Working and Building Lives in U.S. Health CareFrom EverandMigrants Who Care: West Africans Working and Building Lives in U.S. Health CareNo ratings yet

- Health Care for Some: Rights and Rationing in the United States since 1930From EverandHealth Care for Some: Rights and Rationing in the United States since 1930Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Ebola Virus and West Africa: Medical and Sociocultural AspectsFrom EverandThe Ebola Virus and West Africa: Medical and Sociocultural AspectsNo ratings yet

- MPH 690 Culminating Experience Final PaperDocument10 pagesMPH 690 Culminating Experience Final Paperapi-489701648No ratings yet

- Overtreated: Why Too Much Medicine Is Making Us Sicker and PoorerFrom EverandOvertreated: Why Too Much Medicine Is Making Us Sicker and PoorerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (26)

- How to Obtain a Phd (Penalty for Hardworking Dummies) in the United States: Inside OutFrom EverandHow to Obtain a Phd (Penalty for Hardworking Dummies) in the United States: Inside OutNo ratings yet

- Phantom Billing, Fake Prescriptions, and the High Cost of Medicine: Health Care Fraud and What to Do about ItFrom EverandPhantom Billing, Fake Prescriptions, and the High Cost of Medicine: Health Care Fraud and What to Do about ItNo ratings yet

- Tuesday, October 21, 2014 EditionDocument12 pagesTuesday, October 21, 2014 EditionFrontPageAfricaNo ratings yet

- Myths of U.S. HealthcareDocument3 pagesMyths of U.S. HealthcarecherylsealatlargeNo ratings yet

- Dying to be Free How America's Ruling Class Is Killing and Bankrupting Americans, and What to Do About It: How America's Ruling Class Is Killing and Bankrupting Americans, and What to Do About ItFrom EverandDying to be Free How America's Ruling Class Is Killing and Bankrupting Americans, and What to Do About It: How America's Ruling Class Is Killing and Bankrupting Americans, and What to Do About ItNo ratings yet

- Why the U. S. Gets the Worst Childbirth Outcomes In the Industrialized WorldFrom EverandWhy the U. S. Gets the Worst Childbirth Outcomes In the Industrialized WorldNo ratings yet

- Networking Primary Health Care: Mississippi Discovers the Iranian Health SystemFrom EverandNetworking Primary Health Care: Mississippi Discovers the Iranian Health SystemNo ratings yet

- Health Policy Capstone PaperDocument15 pagesHealth Policy Capstone Paperapi-315208605No ratings yet

- Left Shift: How and Why America Is Heading to Second Rate, Single Payer Health Care.From EverandLeft Shift: How and Why America Is Heading to Second Rate, Single Payer Health Care.No ratings yet

- Health Care, Race and CultureDocument6 pagesHealth Care, Race and Culturef5kt8ydcqvNo ratings yet

- Curing Medicare: A Doctor's View on How Our Health Care System Is Failing Older Americans and How We Can Fix ItFrom EverandCuring Medicare: A Doctor's View on How Our Health Care System Is Failing Older Americans and How We Can Fix ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Changing Face of Medicine: Women Doctors and the Evolution of Health Care in AmericaFrom EverandThe Changing Face of Medicine: Women Doctors and the Evolution of Health Care in AmericaNo ratings yet

- TIME Magazine December 1Document99 pagesTIME Magazine December 1rathneshkumar100% (2)

- Healers or Dealers?: True Investigative Stories of Corrupt DoctorsFrom EverandHealers or Dealers?: True Investigative Stories of Corrupt DoctorsNo ratings yet

- Beyond Medicine: Why European Social Democracies Enjoy Better Health Outcomes Than the United StatesFrom EverandBeyond Medicine: Why European Social Democracies Enjoy Better Health Outcomes Than the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Health Equity: A Guide for Clinicians, Medical Educators & Healthcare OrganizationsFrom EverandHealth Equity: A Guide for Clinicians, Medical Educators & Healthcare OrganizationsNo ratings yet

- Ant Final PaperDocument7 pagesAnt Final Paperapi-516978847No ratings yet

- Brave New World of Healthcare Revisited: What Every American Needs to Know about our Healthcare CrisisFrom EverandBrave New World of Healthcare Revisited: What Every American Needs to Know about our Healthcare CrisisNo ratings yet

- Comrades in Health: U.S. Health Internationalists, Abroad and at HomeFrom EverandComrades in Health: U.S. Health Internationalists, Abroad and at HomeNo ratings yet

- Carrying On: Another School of Thought on Pregnancy and HealthFrom EverandCarrying On: Another School of Thought on Pregnancy and HealthNo ratings yet

- Thursday, December 11, 2014 EditionDocument14 pagesThursday, December 11, 2014 EditionFrontPageAfricaNo ratings yet

- Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans: A Concise, Evidence-Based Guide to Important Differences and Better OutcomesFrom EverandPatient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans: A Concise, Evidence-Based Guide to Important Differences and Better OutcomesNo ratings yet

- False Dawn: The Rise and Decline of Public Health NursingFrom EverandFalse Dawn: The Rise and Decline of Public Health NursingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Revitalizing the American Healthcare System: A Comprehensive Guide to Rebuilding, Reforming, and Reinventing Healthcare in the United States: Transforming the Future of Healthcare in America: A Practical and Inclusive ApproachFrom EverandRevitalizing the American Healthcare System: A Comprehensive Guide to Rebuilding, Reforming, and Reinventing Healthcare in the United States: Transforming the Future of Healthcare in America: A Practical and Inclusive ApproachNo ratings yet

- Tafelberg Short: The Politics of Pregnancy: From 'population control' to women in controlFrom EverandTafelberg Short: The Politics of Pregnancy: From 'population control' to women in controlNo ratings yet

- 7th Grade Scheduling Presentation For 8th Grade For The 2022-2023 School YearDocument22 pages7th Grade Scheduling Presentation For 8th Grade For The 2022-2023 School Yearapi-234989244No ratings yet

- CanadaDocument48 pagesCanadaapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Presentation For 5th Grade Students Going To Beer Middle School Next School Year 2022-2023Document24 pagesPresentation For 5th Grade Students Going To Beer Middle School Next School Year 2022-2023api-234989244No ratings yet

- 6th Graders Scheduling For 7th Grade Electives For Next School YearDocument22 pages6th Graders Scheduling For 7th Grade Electives For Next School Yearapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Chapter 12: Canada: 6 Grade Social StudiesDocument27 pagesChapter 12: Canada: 6 Grade Social Studiesapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Problem-Solving PosterDocument1 pageProblem-Solving Posterapi-234989244No ratings yet

- 2022-23 Grade 7-Selection CardDocument2 pages2022-23 Grade 7-Selection Cardapi-234989244No ratings yet

- For Current 7th Graders Scheduling Slideshow For Scheduling Your Elective Classes For The 2022-2023 School YearDocument6 pagesFor Current 7th Graders Scheduling Slideshow For Scheduling Your Elective Classes For The 2022-2023 School Yearapi-234989244No ratings yet

- 2022-23 Grade 8-Selection CardDocument1 page2022-23 Grade 8-Selection Cardapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Empathy PosterDocument1 pageEmpathy Posterapi-234989244No ratings yet

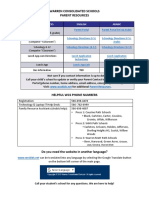

- Parent ResourcesDocument1 pageParent Resourcesapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Mental Health Help If NeededDocument1 pageMental Health Help If Neededapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Students Who Know They Are Going To Be Missing School Should Do The FollowingDocument1 pageStudents Who Know They Are Going To Be Missing School Should Do The Followingapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Parent Login For SchoologyDocument3 pagesParent Login For Schoologyapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Ms-Mathmindsetcamp For 6th and 7th GradersDocument1 pageMs-Mathmindsetcamp For 6th and 7th Gradersapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Ms-Literacycamp For 6th and 7th GradersDocument1 pageMs-Literacycamp For 6th and 7th Gradersapi-234989244No ratings yet

- GvsugeneralinformationDocument1 pageGvsugeneralinformationapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Canada and United States Map Study GuideDocument3 pagesCanada and United States Map Study Guideapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Parent ResourcesDocument1 pageParent Resourcesapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Svsu AdmissionsDocument22 pagesSvsu Admissionsapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Mich Tech AdmissionsDocument13 pagesMich Tech Admissionsapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Ltu AdmissionsDocument31 pagesLtu Admissionsapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Nmu AdmissionsDocument30 pagesNmu Admissionsapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Welcome To XelloDocument1 pageWelcome To Xelloapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Contact Information For Mental Health Providers Here at Beer MsDocument1 pageContact Information For Mental Health Providers Here at Beer Msapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Logging Into XelloDocument4 pagesLogging Into Xelloapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Schoology App DirectionsDocument3 pagesSchoology App Directionsapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Mental Health ResourcesDocument2 pagesMental Health Resourcesapi-234989244No ratings yet

- Resources For Macomb County ResidentsDocument22 pagesResources For Macomb County Residentsapi-234989244No ratings yet

- No Cost Telehealth Therapy For Middle and High School Macomb County StudentsDocument1 pageNo Cost Telehealth Therapy For Middle and High School Macomb County Studentsapi-234989244No ratings yet

- 2 1 1000Document100 pages2 1 1000Dr-Mohammed AdelNo ratings yet

- Headache - 2001 - Jacome - Transitional Interpersonality Thunderclap HeadacheDocument4 pagesHeadache - 2001 - Jacome - Transitional Interpersonality Thunderclap HeadacheactualashNo ratings yet

- Modified Double Glove TechniqueDocument1 pageModified Double Glove TechniqueSohaib NawazNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Dummy ReportDocument2 pagesCOVID-19 Dummy ReportVirat DaineNo ratings yet

- ICMIDocument4 pagesICMIKim MingyuNo ratings yet

- How Can Women Make The RulesDocument0 pagesHow Can Women Make The Ruleshme_s100% (2)

- Proceedings Tri-State Dairy Nutrition ConferenceDocument140 pagesProceedings Tri-State Dairy Nutrition Conferencepedro41No ratings yet

- Influenza: CausesDocument2 pagesInfluenza: CausesMaui ShihtzuNo ratings yet

- Choosing the Right PaediatricianDocument263 pagesChoosing the Right PaediatricianSuneethaVangala100% (1)

- Comp ReviewDocument99 pagesComp ReviewTHAO DANGNo ratings yet

- How To Measure Frailty in Your PatientsDocument1 pageHow To Measure Frailty in Your PatientsZahra'a Al-AhmedNo ratings yet

- PMO - Pasteurized Milk OrdinanceDocument340 pagesPMO - Pasteurized Milk OrdinanceTato G.k.No ratings yet

- Protein and Amino Acid MetabolismDocument52 pagesProtein and Amino Acid MetabolismRisky OpponentNo ratings yet

- Physical Assessment FormDocument14 pagesPhysical Assessment FormHedda Melriz DelimaNo ratings yet

- Nat Ag Winter Wheat in N Europe by Marc BonfilsDocument5 pagesNat Ag Winter Wheat in N Europe by Marc BonfilsOrto di CartaNo ratings yet

- Surgery in Hymoma and MGDocument11 pagesSurgery in Hymoma and MGHeru SigitNo ratings yet

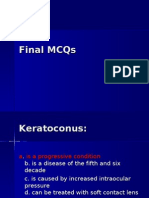

- MCQs 08Document39 pagesMCQs 08api-3736493100% (2)

- Abdominal ExaminationDocument14 pagesAbdominal ExaminationValeria Guerra CastilloNo ratings yet

- Dangers of Excess Sugar ConsumptionDocument2 pagesDangers of Excess Sugar ConsumptionAIDEN COLLUMSDEANNo ratings yet

- Covid 19 BookletDocument10 pagesCovid 19 BookletNorhanida HunnybunnyNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care of Clients Undergoing Eye SurgeryDocument1 pageNursing Care of Clients Undergoing Eye SurgerySewyel GarburiNo ratings yet

- Cellular Detox Smoothies PDFDocument20 pagesCellular Detox Smoothies PDFRuth Engelthaler100% (2)

- Bacterial ReproductionDocument12 pagesBacterial Reproductionchann.maahiNo ratings yet

- Article Dietschi VeenersDocument18 pagesArticle Dietschi VeenersRoberto PucNo ratings yet

- ConventionalDocument9 pagesConventionaltabbsum hussainNo ratings yet

- The Decline and Fall of Pax Americana, by DesertDocument200 pagesThe Decline and Fall of Pax Americana, by DesertDHOBO0% (1)

- Nursing Care Plan #1 Assessment Explanation of The Problem Goal/Objective Intervention Rational EvaluationDocument10 pagesNursing Care Plan #1 Assessment Explanation of The Problem Goal/Objective Intervention Rational EvaluationmalindaNo ratings yet

- The Function of Vitamins and Mineral in Hair LossDocument2 pagesThe Function of Vitamins and Mineral in Hair LossDian AcilNo ratings yet

- JKNKLKLDocument10 pagesJKNKLKLCyntia AndrinaNo ratings yet

- COO Job Description PDFDocument4 pagesCOO Job Description PDFkjel reida jøssanNo ratings yet