Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Valdai Paper #12: U.S. Foreign Policy After The November 2014 Elections

Uploaded by

Valdai Discussion ClubOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Valdai Paper #12: U.S. Foreign Policy After The November 2014 Elections

Uploaded by

Valdai Discussion ClubCopyright:

Available Formats

Valdai Papers

#12 | April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the

November 2014 Elections

Paul J. Saunders

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

Assessing the possible foreign policy consequences of Americas turn toward the right requires a

multi-layered approach built around four key questions:

What happened in the November 2014 mid-term electionsand why?

What are conservative/Republican views on foreign policy and how do they relate to the

perspectives of liberals/Democrats and independents?

How will Americas political system and government institutions adjust to reflect the election

outcome and shifting opinion?

And finally, how will this affect U.S. foreign policy on specific issues?

The Mid-Term Elections

The Republican Party won a major victory in the 2014 mid-term elections, securing control of both

houses of Congress for the first time since 2005-06. More concretely, the GOP gained 13 seats in the

House of Representatives and 9 seats in the Senate. Of less importance to foreign policy but quite

significant as a reflection of political dynamics in the United States, Republicans won a net increase

of two governorshipsnow controlling 31 of 50and secured full control of 30 state legislatures (and

in addition to majorities in one of two houses in an additional eight states).

Nevertheless, the November 2014 elections were not foreign policy elections. Indeed, with the

exception of the 2004 election (when George W. Bush was re-elected in part due to his strong

response to the September 11 attacks), and the 2006 and 2008 elections (when many voters were

frustrated by the ongoing war in Iraq), foreign policy has rarely had significant impact on voting

behavior in the United States.

In 2014, GOP leaders owed their success to Republican anger with President Obama (which increased

Republican turnout), Democratic disappointment with Obama (which reduced Democratic turnout),

and the fact that a large number of Senate seats held by Democratsin states that often lean

Republicanwere at stake. Beyond this, the Republican Party leadership made a concerted effort to

identify and promote mainstream candidates considered less likely to alienate voters than some of

the partys Senate candidates in recent election cycles. The fact that just 38% of Americans approved

of Obamas job in handling foreign policy in September contributed to Republican and Democratic

attitudes toward the president, but views of his policies on the economy, health care, and immigration

were much more important.

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

With this in mind, the election does not provide a clear foreign policy mandate to Republicans in the

Senate and the House of Representatives. Moreover, because the election results had a great deal to

do with attitudes toward Obama, who will be leaving office after the 2016 election, and with the

particular Senate seats that Republicans won, the 2014 election results do not guarantee continued

Republican control of the Congress or victory by a Republican presidential candidate in 2016. At the

same time, the Republican Party is increasingly divided on foreign policy and national security

issueswhich means that GOP control of the Congress (or a Republican president in 2016) could

mean many different things.

Republican Perspectives

Analyzing Republican perspectives on foreign policy and national security requires thinking on three

levelspublic opinion, elite opinion, and elected officials. Each is unique in important respects.

One key issue is the degree to which Republicans (or Democrats or independents) have systematic

and coherent foreign policy views rather than a collection of instinctive reactions to individual issues.

Broadly speaking, those within the policy elitescolumnists, pundits, experts, and some former

officialsare more likely to have comprehensive foreign policy perspectives that fall within an

established school of thought. Among the public and elected officials, relatively few individuals pay

sustained attention to international affairs or U.S. foreign policy. This is largely a matter of time;

policy elites spend far more time on these issues than the American public (who are not policy

professionals) or elected officials (who often focus more on politics than policy).

Because discussing policy is their profession, the policy elites tend to dominate national debates on

foreign policy issues (except in periods of crisis, when elected leaders become engaged). This in turn

means that efforts to analyze U.S. foreign policy tend to focus on which elite school of thought is

dominant in national debates and to interpret public opinion and statements by elected leaders as

reflecting the rise or fall of a particular approach. Reality is far more complex.

Nevertheless, it may be useful to outline briefly the major schools of thought on foreign policy and

national security among Republicans. Because the following descriptions are deliberately brief, they

are somewhat general and oversimplified. Moreover, none of the groups is totally monolithic or

exclusive.

Libertarians, also often known as non-interventionists, are skeptical toward the use of force, foreign

basing of U.S. military personnel and high defense budgets. This derives from rejection of a strong

national security state as a great danger to American libertya greater danger than many foreign

threats, because of U.S. power. They often advocate against executive authority and in favor of

greater congressional oversight. Former Congressman Ron Paul has been a prominent libertarian

voice.

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

National security conservatives support a strong military and active use of U.S. military force. They

tend to prefer quick and effective unilateral U.S. action to slower half-measures with broader

multilateral support. Unlike neo-conservatives, they are generally reluctant to engage in nationbuilding. Former Under Secretary of State John Bolton is a prominent example.

Neo-conservatives also support a strong military actively employed. They define Americas foreign

policy goals more expansively than national security conservatives and seek to use U.S. power to

promote American values internationally. Neo-conservatives tend to see conflict between

democracies and non-democracies as historically inevitable. Commentator William Kristol is a

leading neo-conservative.

Paleo-conservatives, like libertarians, are reluctant to become involved in international conflicts.

However, they generally favor a strong American military, which paleo-conservatives see as focused

narrowly on defending the United States. Paleo-conservatives often emphasize the international

importance of Western civilization and its Christian foundations. Commentator and former

presidential candidate Patrick Buchanan is often identified as a paleo-conservative.

Realists are selective in the use of force and generally support military action only when vital or

extremely important national interests are at risk or when costs are low and the probability of success

is high. They oppose nation-building and favor pragmatic approaches to achieving strategic

objectives. Unlike libertarians and paleo-conservatives, however, they support active U.S.

international leadership. Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger is a quintessential realist.

While the adherents to these five major trends within the Republican Party differed to some extent

during the Cold Warfor example, over dtente, which realists supported but national security

conservatives and neo-conservatives opposedthe end of the Cold War has considerably sharpened

their disagreements. Many of the groups have crossed party lines to back policies advocated by

Democratic presidents or have opposed policies advocated by a Republican president. (Conversely,

liberal interventionist Democrats often supported President George W. Bushs policies in Iraq and

Afghanistan.)

For example, neo-conservatives supported the Clinton administrations involvement in the former

Yugoslavia and its humanitarian interventions, libertarians, national security conservatives, paleoconservatives and realists opposed the moves. Likewise, only neo-conservatives supported the Bush

administrations efforts to occupy and democratize Iraq, though national security conservatives and

many realists supported the narrower goal of removing Saddam Hussein from power. Libertarians

and paleo-conservatives largely opposed the war. Realists have generally supported the Obama

administrations negotiations with Iran, which national security conservatives and neo-conservatives

oppose. Neo-conservatives and national security conservatives criticized the Obama administration

for doing too little in the war in Libya, while realists, libertarians and paleo-conservatives generally

opposed the intervention.

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

Nevertheless, intellectual policy debates occurred primarily within the foreign policy elite. Among

elected officials and the public, most individuals do not have a coherent and well-developed foreign

policy philosophy. As a result, case-by-case by instinctive reactions and wider political context shape

their attitudes on specific issues. Elite policy debates can establish the framing and the vocabulary

for these political and public discussions, and can influence the agenda to some extent, but typically

do not drive concrete policy decisions.

On the contrary, politics is the main driver of foreign policy discussion and, as a result, elected

officials tend to engage in political debates rather than policy debates. Because they can receive

considerable media attention, elected officials substantially influence which issues are under public

discussion at any given time. At the same time, since television producers usually seek two clearly

opposing viewpoints rather than three, four or five, members of the policy elite who appear on

television often discuss foreign policy within the two-party political frame. This is especially true of

experts and former officials who aspire to political appointments in the next Republican (or

Democratic) administration.

National, state and local Republican Party organizations are also important in understanding

Republican perspectives on foreign policy. These organizations form the transmission belt that

conveys national-level policy positions and perspectives to Republican Party activists across the

United States. The professionals in these organizations are primarily political operatives whose

principal experience is in managing political campaigns. Volunteerswho far outnumber the

professionalsare ordinary citizens who are intensely interested in Americas political process. Few

work professionally in international affairs or related fields.

As a practical matter, this means that state and local Republican Party organizations will generally

reflect national-level GOP positionswhatever they may be at any particular time. While there may

be state-by-state variation on particular issues due to political conditions, this is far more likely to

affect domestic policy issues than foreign policy. Thus, for example, Republicans in relatively liberal

states like California or Massachusetts often deviate from the national party on social issues. Some

Republicans in the southwest have complicated national-level efforts to adjust the partys positioning

on immigration. The most significant state/local influences on the politics of foreign policy are

typically military bases (which produce greater support for defense spending), export

industries/commodities (which produce greater support for free trade and opposition to embargos

and sanctions), and large immigrant communities (which can produce greater interest in a particular

country or region).

However, national-level Republican Party positions have considerably greater impact when a

Republican president is in the White House. Under a Democratic president, Republicans in Congress

and national party organizations face greater challenges in presenting a unified messageparticularly

over time. Thus, at the beginning of the Obama administration, many state and local Republicans

continued to articulate Bush-era perspectives. As time passed, however, the absence of a clear

centrally defined message facilitated greater debate at the state and local levels because Bush-era

positions were no longer expected Republican positions on a national basis.

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

In addition, Republican Party organizations matter primarily to Republican activists, who are a small

share of all Republicans. Activists can be very influential in some areassuch as in primary elections

for presidential, Senate and House candidatesbut have a limited role in shaping the views of

average Americans who consider themselves Republicans or sympathize with the Republican Party.

Broadly speaking, Americans pay the most attention to foreign policy when something is going

wrongthat is, when they see a threat or when they believe that the president has made a mistake.

As a result, public opinion tends to evolve in response to events (as perceived threats arise) and in

response to policy (when it appears to fail). Politically engaged Americans may take cues from

elected officials, party organizations, or policy elites, but also form their own views.

What do Republicans think about U.S. foreign policy? Since 2006, the share of Republicans who

believe that the United States should stay out of world affairs has grown steadily in regular polling

by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, from approximately 20% in 2006 to 40% in May 2014.

However, the Chicago Councils report Foreign Policy in the Age of Retrenchment (2014) makes clear

that for Republicansand Americans more broadlystaying out of world affairs does not mean

isolationism or disengagement. Rather, the report states, it means being more selective than average

when it comes to economic assistance, military expenditures, and the use of force while continuing

to support many forms of international engagement, including alliances, diplomacy, trade

agreements, and treaties and to being prepared to respond to direct threats to the United States.

This greater selectivity in part reflects the fact that only 40% of Republicans (and 20% of Democrats)

now say that the war in Iraq was worth fighting. Only 34% of Republicans say that the war in

Afghanistan was worth fighting.

With respect to specific issues, according to the Chicago Council, Americans see cyber-attacks (69%),

terrorism (63%), and acquisition of nuclear weapons by unfriendly countries (60%) as the critical

national security threats. (Note that the survey took place before the high-profile cyber-attacks on

Sony Pictures that the U.S. government attributed to North Korea.) For comparison, 38% see

Russias territorial ambitions as a critical threat, while 24% see the civil war in Syria as critical. A

Pew Research Center poll that asked Americans to identify major threats (a major threat is likely

somewhat less dangerous than a critical threat) in August 2014 shows similar results. In the Pew

survey, 80% named Islamic extremist groups like al Qaeda a major threat, with ISIL (78%) and Irans

nuclear program (74%) close behind. Fifty-four percent described growing tension between Russia

and its neighbors as a major threat.

Notably, in the Chicago Councils poll, the desire to stay out of world affairs was most widespread

among political independents (48%) and more common among Republicans (40%) than Democrats

(35%). However, public opinion has continued to evolve in the months since the Chicago Council poll

as Americans been disappointed with the Obama administrations responses to the so-called Islamic

State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and to Russias conduct in Ukraine. While the question is subtly

different, polling by the Pew Research Center shows a significant increase in the share of Americans

who say that the United States does too little in helping solve world problems. Over the same period,

the share of Americans believing that the United States does too much fell from 51% to 39%.

Significantly, the percentage of Republicans agreeing with the statement that the United States does

too little more than doubled over this periodfrom 18% to 46%. To be clear what doing too little

means, 77% of Republicans (and 54% of all Americans) said that President Obama is not tough

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

enough in his approach to foreign policy and national security issues. Significantly, in the August

2014 Pew survey 57% of Republicans supported sending ground troops to Iraq and Syria to fight

ISILa sharp increase from earlier polling.

What remains unclear is whether the recent hardening in Republican foreign policy attitudes will

endure or, conversely, whether it may subside if attacks on ISIL appear to be succeeding, slow

progress continues in talks with Iran, and the conflict in Ukraine remains relatively quiet. Because

public opinion is reactive, it will continue to evolve as events unfold and Americans evaluate their

governments policy responses. For the time being, however, Republicans (and Americans) appear

divided on how active Washington should beparticularly in its use of military force.

Perspectives and Policy

The third key issue in understanding how the Republican successes in the November 2014 elections

and broader trends in American society will affect U.S. foreign policy is an analysis of Americas

policy process. Specifically, what impact can Republican control of the Congress and Republican

perspectives within policy elites and the American public have on specific policy decisions?

First, it is necessary to recognize that even a weak president facing a hostile Congress has

considerable authority to make foreign policy. As the nations chief executive, the president controls

government agencies that implement foreign policy and, as commander-in-chief of the armed forces,

the president can order the use of military forcethough it can be more difficult to sustain costly

operations. Though Congress appropriates the money that allows the executive branch to act,

exercising this control takes time and creates a variety of political complications. In the short-term,

the executive branch has broad discretion.

Second, divisions among Republicans on important foreign policy and national security issues

especially the use of force and defense spendingwill give President Obama more flexibility in

making policy. These divisions can also produce unexpected results in the Congress; for example, few

observers expected the budget sequestration provisions in the 2011 Budget Control Act to take effect

because most expected that Congressional Republicans would be unwilling to accept indiscriminate

cuts in the defense budget and, as a result, saw good chances for a compromise deal during

negotiations among the Super-Committee established under the law. This analysis was incorrect

because many newly elected fiscal conservatives preferred the defense cuts (along with cuts in social

programs) to a bad deal with Congressional Democrats.

At the same time, America will focus increasingly on its 2016 presidential election during coming a

year and a half. In this environment, Republican leaders in the Senate and the House of

Representatives will be seeking opportunities to contrast their priorities and positions with those of

the Obama administration. Because many see the president as insufficiently tough, Republicans will

be particularly tempted to appear tough themselves. Since the American public is skeptical of deeper

military involvement in Iraq and Syria, this may mean tougher positions on Russia, Iran and North

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

Korea. If nothing unexpected happens, Republican divisions on Cuba will probably prevent the

Congress from acting there. At the same time, Republicans will want to demonstrate that they are

prepared to govern and therefore that they are able to work with Democrats on some foreign policy

issuesespecially trade, where the two parties have a shared interest in steps that could stimulate

continued economic growth and create jobs.

In view of the divisions among Republicans, from a foreign policy perspective some of the most

important questions moving forward will relate to the 2016 election. Who is the Republican 2016

presidential nominee? What foreign policy outlook will that individual bring to the campaign (and to

a possible term in office)? And will Congressional Republicans, Republican policy elites and

Republican-leaning voters eventually unify behind the partys candidate?

It is far too early to attempt to predict the identity of the nominee. However, it has already become

clear that few of the leading candidates have significant foreign policy experience. Many are

governorssuch as New Jerseys Chris Christie, Floridas Jeb Bush, and Wisconsins Scott Walker

who by definition have focused overwhelmingly on the affairs of their individual states and have

limited foreign policy experience. (According to recent news reports, former Massachusetts Governor

Mitt Romney may also run again; he has somewhat more international experience due to his business

career.) Two of the candidates with the most experienceSenator Marco Rubio and Senator Rand

Paulhave served in the Senate for only four years, though each has served on relevant committees

(Rubio on Foreign Relations and Intelligence, Paul on Homeland Security and Foreign Relations).

Rubio and Paul also have the most clearly-defined foreign policy perspectives, with Rubio generally

reflecting neo-conservative attitudes and Paul identifying himself repeatedly as a foreign policy realist

(and distancing himself from some but not all of his father former Congressman Ron Pauls

libertarian positions).

Although the Bush administrations foreign policy philosophya combination of neo-conservative

and national security conservative approaches with some realist elementsremains dominant within

the GOP, realist-libertarian skepticism toward frequent military interventions has clearly grown. In

this environment, and when President Obama is seen as too weak in foreign policy, a candidate with

this general direction will likely have an easier time unifying the party than a more overtly realistoriented candidate. In fact, some suggest that neo-conservatives would support former Secretary of

State Hillary Clinton over Rand Paul on foreign policy grounds.

Nevertheless, as history has shown, a candidates campaign positions on foreign policy and national

security matters are not powerful predictors of foreign policy decisions. For example, candidate

George W. Bush famously called for a more humble foreign policy and opposed nation-building,

while candidate Barack Obamas opposition to the Iraq war did not prevent him from deciding to

intervene in Libya. (Obama also of course pledged to close the U.S. detention facility at Guantanamo

Bay, but has not done so.) As a result, it is quite difficult to foresee how a hypothetical Republican

president might go about making foreign policy in 2017, except in the most general terms.

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

The Policy Process

Broadly speaking, Congressional Republicans have three tools at their disposal: hearings and

investigations, non-binding resolutions, and binding legislation. Of course, the power to pass

legislation includes control over budget appropriations. Senate Republicans can also delay or obstruct

appointments of senior officials and diplomats andif President Obama should sign any formal

international treaties rather than executive agreementsratify or block treaties.

From a political perspective, hearings are well suited to demonstrating quick action to respond to

public concerns, obvious policy failures, or potential wrongdoing. Hearings apply political pressure

but do not produce specific policy outcomes. Investigations obviously require much more time, but

can be useful in ensuring sustained attention to a particular topic. However, investigations can be

politically damaging if they do not produce credible outcomes suggesting wrongdoing.

The Republican Congress could also pass non-binding resolutions quickly for symbolic reasons. As a

practical matter, however, these resolutions usually receive minimal media and public attention

andespecially when passed on a party-line voteare often quickly dismissed. Still resolutions can

be useful in attracting attention to an issue without requiring any particular actionsomething

important when Republicans are divided or, alternatively, when they do not have a concrete policy

proposal.

If Republicans elect to pass legislation on foreign policy, President Obama of course retains veto

power. Overturning a presidential veto would require significant support from Democratsin which

case Mr. Obama would have bigger political problems that he does not appear to have now.

Nevertheless, an opposing party controlling the Congress may attempt to force a veto to clarify the

presidents position for its own political benefit.

The federal budget may well become such an issue, in that Republicans have complained for some

time about the Democratic Senates delays in passing budgets. Under the circumstances, Republicans

may seek to demonstrate both that they can pass a budget on time and that it will reflect their

political priorities. Whether or not the White House objects to the defense and foreign policy

components of a Republican budget, the president may veto such a budget on domestic political

grounds, complicating State Department and Pentagon operations.

Policy elites generally have limited impact on specific actions by Congress, or by the executive branch,

for several reasons. First, they are obviously not directly involved in the decision-making process and

therefore clearly lack any formal role. Second, because they are not directly involved, policy elites as

a whole tend to lack sufficient up-to-date information to formulate concrete and detailed policy

proposals. Third, legislators and executive branch officials seek to avoid the impression that outside

individuals or groups shape policy decisions. Finally, the unpredictable pace of decision-making can

make it difficult for anyone not directly involved in the process to contribute.

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

Nevertheless, elites can have a significant role in the overall policy process by shaping the agenda and

framing debate. This does not produce specific outcomes but can support or discourage broad

approachesmaking it easier or more difficult for the administration or the Congress to pursue a

particular direction.

Policy elites exercise influence in one way by adding or removing issues from the day-to-day policy

agenda through the attention and priority they receive. For example, the policy and media elites put

pressure on the administration to take action against ISIL by dedicating substantial attention to its

brutal killing of two Americans. Elites applied similar pressure over the spread of Ebolaespecially

after cases appeared in the United States. Elites often also encourage humanitarian assistance and

defense of human rights.

Once a particular issue is on the agenda, policy elites influence decision-making through framing

that is, by discussing the issue in ways that make specific approaches more or less likely. For

example, while the Bush administration put the invasion of Iraq onto the agenda, policy elites made it

more likely by underestimating its costs. Likewise, Russia put Ukraines territorial integrity onto the

agenda, but elite attitudes towards Russias government and perceived objectives generated framing

that encouraged a harsh American response (while also minimizing perceived risks to the United

States from such an approach). Conversely, divisions within the policy elite over Syrias civil war

reduced pressure on the Obama administration and provided the White House with greater flexibility

until chemical weapons attacks and the later rise of ISIL in Iraq each affected how elites framed the

conflict, leading to greater pressure on the president to act.

Where Republican policy elites are dividedagain, particularly over defense spending and the use of

forcethey will contribute to divisions within the wider elites. As described above, this can increase

the presidents room for maneuver on related issues.

Public opinion shapes policy in much the same manner as elite opinion. However, where those in the

elites express their perspectives in 800-word opinion articles or 15-second television clips, public

opinion manifests itself in fractions of sentences drawn from opinion surveys. Thus, public opinion is

even less able to produce specific policies and serves primarily as a broad guide or general sense of

direction. Because Republican public opinion is dividedlike Republican elite opinionit is less

useful in predicting the political pressures that the administration will face during coming a year and

a half.

Implications for U.S. Policy

The most significant near-term policy consequences after Americas November 2014 elections and the

broader rightward trends it exposed will derive from Republican control of both houses of the U.S.

Congress and Republican leaders sense that President Obama is politically vulnerable on foreign

policy.

10

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

Republicans in Congress can demonstrate their toughness in several ways. One is to get tough on

the administrationorganizing hearings and investigations of the administrations policy decisions to

generate political pressure. Recent hearings and reports on the death of four U.S. diplomats in

Benghazi, Libya are an example of this. The administrations rebalancing policy in East Asia could

be one target for hearings as a way to position Republicans as stronger on security issues without

requiring an increase in the defense budget, which would divide Republicans, or any specific steps to

confront China. Americans are worried about China47% see U.S. debt to China as a critical issue

and 41% see Chinas development as a world power as critical. However, absent any immediate

crisis, China has not been a top policy priority. With help from sympathetic Republican policy elites,

Congressional Republicans could try to exploit existing public concerns about China to their political

advantage.

On Iran, many Congressional Republicans will likely continue to criticize the administrations

willingness to negotiate with Iran and to outline key conditions they expect in any deal. However,

there are significant divisions over how best to proceed. Many Republicans support draft legislation

from Senators Mark Kirk (R-IL) and Robert Menendez (D-NJ) that would automatically impose new

sanctions if there is no agreement with Iran by June 30. Othersincluding Senate Foreign Relations

Committee Chairman Bob Corker and Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman John McCain

back a milder approach intended to force Mr. Obama to send any eventual deal to the Congress for

approval. Sentiment is growing in the Congress that the legislative branch needs to reassert its

oversight role on foreign policy matters, and this latter approach may win bipartisan support. If the

Congress forces the president to seek its approval, Americas domestic politics could make it quite

difficult to reach a lasting agreement.

With respect to Russia, Republicans appear unlikely to pass new legislation without a new crisis on

the ground in Ukraine. They are more likely to pursue hearingsperhaps continuing an existing line

of pressure related to Russias alleged violation of arms control commitments and the

administrations relatively weak response. If the administration attempts to reduce tensions with

Moscow, which appears to be its current goal, it is likely to encounter resistance from Republicans

unwilling to reduce or remove sanctions imposed by Congress (as distinct from those introduced by

executive order).

In the Middle East, Republicans remain divided over key issues, including whether or not the United

States should expand its attacks on ISIL, possibly including ground troops, and whether or not to

provide significant military assistance to Syrias rebels combating the Assad government. As a result,

the administration is more likely to face sharp public criticism from individual Republicans

particularly some prominent members of the U.S. Senatethan any concrete action. However, taking

into account, Senator John McCains new role as Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee,

administration officials may also confront greater pressure to defend their approach to these issues

and to explain what they have done.

The administrations recent opening to Cuba has divided Republicans, leading to a public

disagreement between Senator Rand Paul (who supported the White House) and Senator Marco

Rubio (who has a Cuban family background) on social media. Arizona Senator Jeff Flake has also

supported President Obama. However, while the administration may have enough support to avoid

hostile legislation, it likely does not have enough to pass legislation to remove sanctionsespecially

11

#12, April 2015

U.S. Foreign Policy after the November 2014 Elections

because the Senate Foreign Relations Committees top Democrat, New Jersey Senator Bob Menendez

(who also has a Cuban family background), is deeply skeptical of engaging with Havana.

More broadly, the administrations policies toward Cuba, Iran and Russia could force a major debate

on the U.S. use of economic sanctions during 2015 and 2016. In all three cases, the United States

may have to choose between continuing economic sanctions at the expense of other steps to improve

these three complex relationships to advance U.S. national interests. At this point, Republicans in

Congress, Republican policy elites and Republicans in general tend to favor economic sanctionsas

do most Americansas a useful alternative to military action. However, as ties to Cuba, Iran and

Russia evolve, ongoing sanctions may force closer examination and deeper discussion of sanctions

and their effectiveness in achieving U.S. goals.

It is of course impossible to separate Republican perspectives and politics from Americas wider

society in a debate like this or, indeed, in discussions of any major issue. In these cases, broad elite

and public opinion, and potential bipartisan coalitions involving factions sympathetic to each party as

well as independent voters, may be more significant than Republican views alone. From this pointof-view, the real competition over U.S. foreign policy might be between a neo-conservative/liberalinterventionist coalition more supportive of assertive use of force (and defense spending to sustain it)

and a realist/libertarian/liberal internationalist/liberal coalition more skeptical of the use of force

(Democratic liberal internationalists generally prefer multilateral diplomacy over force and usually

want UN Security Council authorization for military action; liberals oppose most if not all military

action). National security conservatives would likely support the more assertive group in using

forcebut not in nation-buildingwhile paleo-conservatives could support the more assertive group

on the defense budget (but not on interventions).

Finally, it is useful to remember that one side or the other rarely wins any truly important political

debate. Such cases do exist, but they have required long and slow processes of consensus-building

rather than success in elections or a particular vote in Congress (in fact, the important votes usually

come at the end of this process). With this in mind, shifting approaches to issues like defense

spending, the use of force, or economic sanctions are often largely reactions to perceived mistakes

that will continue only so long as there are no new errors. Then the pendulum will swing in the other

direction, whatever it may be.

About the author:

Paul J. Saunders, Executive Director of The Nixon Center and Associate Publisher of The National

Interest. He served in the State Department from 2003 to 2005.

12

#12, April 2015

You might also like

- FM 7-8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and SquadDocument411 pagesFM 7-8 Infantry Rifle Platoon and SquadJared A. Lang75% (4)

- E.J. Dionne Jr.’s Why the Right Went Wrong: Conservatism - From Goldwater to the Tea Party and BeyondFrom EverandE.J. Dionne Jr.’s Why the Right Went Wrong: Conservatism - From Goldwater to the Tea Party and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Evangelicals Israel and US Foreign PolicyDocument21 pagesEvangelicals Israel and US Foreign PolicyMohd Zulhairi Mohd NoorNo ratings yet

- The Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized EraFrom EverandThe Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized EraNo ratings yet

- The Hell of Good Intentions: America's Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. PrimacyFrom EverandThe Hell of Good Intentions: America's Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. PrimacyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- JFKSWCS FY15 AcademicHandbookDocument56 pagesJFKSWCS FY15 AcademicHandbookrcsadvmedia100% (1)

- Operation Urgent FuryDocument40 pagesOperation Urgent FurygtrazorNo ratings yet

- US V SussmannDocument21 pagesUS V SussmannTechno Fog92% (12)

- Beyond Liberal and Conservative: Reassessing the Political SpectrumFrom EverandBeyond Liberal and Conservative: Reassessing the Political SpectrumNo ratings yet

- RoutineVol 1 PDFDocument350 pagesRoutineVol 1 PDFTariq Hussain Khan80% (5)

- The World Order: New Rules or No Rules?Document28 pagesThe World Order: New Rules or No Rules?Valdai Discussion Club100% (2)

- Unstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political StalemateFrom EverandUnstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political StalemateNo ratings yet

- Summary, Analysis & Review of Christopher H. Achen’s & Larry M. Bartels’s Democracy for RealistsFrom EverandSummary, Analysis & Review of Christopher H. Achen’s & Larry M. Bartels’s Democracy for RealistsNo ratings yet

- Strategic Depth in Syria - From The Beginning To Russian InterventionDocument19 pagesStrategic Depth in Syria - From The Beginning To Russian InterventionValdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Sailing the Water's Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign PolicyFrom EverandSailing the Water's Edge: The Domestic Politics of American Foreign PolicyNo ratings yet

- Case Study Al ShabaabDocument15 pagesCase Study Al ShabaabsalmazzNo ratings yet

- A Strong State: Theory and Practice in The 21st CenturyDocument9 pagesA Strong State: Theory and Practice in The 21st CenturyValdai Discussion ClubNo ratings yet

- Digital SignatureDocument22 pagesDigital SignatureDiptendu BasuNo ratings yet

- Has The American Public Polarized?Document24 pagesHas The American Public Polarized?Hoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- The Foreign Policy Disconnect: What Americans Want from Our Leaders but Don't GetFrom EverandThe Foreign Policy Disconnect: What Americans Want from Our Leaders but Don't GetNo ratings yet

- CH01 MSCoE Staffs Above BDE FY23 (24JUN22)Document35 pagesCH01 MSCoE Staffs Above BDE FY23 (24JUN22)geraldwolford1100% (2)

- Digital Fortress Book Review FinalDocument7 pagesDigital Fortress Book Review FinalPEMS Ivan Theodore P LopezNo ratings yet

- Divisions of The NKVD 1939-1945Document14 pagesDivisions of The NKVD 1939-1945rapira3100% (3)

- Filipino History 01 Japanese InvasionDocument68 pagesFilipino History 01 Japanese InvasionXierre ScarletNo ratings yet

- Law Enforcement Administration - NotesDocument117 pagesLaw Enforcement Administration - NotesCristina Joy Vicente Cruz93% (82)

- Reflecting On The Revolution in Military Affairs: Implications For The Use of Force TodayDocument14 pagesReflecting On The Revolution in Military Affairs: Implications For The Use of Force TodayValdai Discussion ClubNo ratings yet

- Summary of Why the Right Went Wrong: by E.J. Dionne | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of Why the Right Went Wrong: by E.J. Dionne | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Assesing Leadership StyleDocument50 pagesAssesing Leadership StyleRaluca SăftescuNo ratings yet

- Tourist Visa Extension: Bi Form No. Tvs-C-Ve-2016 Checklist of Documentary Requirements ForDocument1 pageTourist Visa Extension: Bi Form No. Tvs-C-Ve-2016 Checklist of Documentary Requirements ForKayelyn LatNo ratings yet

- Ballots, Bullets, and Bargains: American Foreign Policy and Presidential ElectionsFrom EverandBallots, Bullets, and Bargains: American Foreign Policy and Presidential ElectionsNo ratings yet

- Summary of Why the Right Went Wrong: by E.J. Dionne | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of Why the Right Went Wrong: by E.J. Dionne | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Analyzing America'S 2008 Presidential Election: By: Mounzer Sleiman PH.DDocument13 pagesAnalyzing America'S 2008 Presidential Election: By: Mounzer Sleiman PH.DammarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 PDFDocument41 pagesChapter 6 PDFAaron ChanNo ratings yet

- 9 - CH 6 Part 2Document2 pages9 - CH 6 Part 2Mr. ChardonNo ratings yet

- M Abdullah Javed (4330)Document9 pagesM Abdullah Javed (4330)Sardar KhanNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Social Media On Donald Trump's Win in The 2016 Presidential ElectionsDocument21 pagesThe Influence of Social Media On Donald Trump's Win in The 2016 Presidential ElectionsEddNo ratings yet

- Free Download The Trump Doctrine and The Emerging International System Stanley A Renshon Full Chapter PDFDocument51 pagesFree Download The Trump Doctrine and The Emerging International System Stanley A Renshon Full Chapter PDFbrooke.houde963100% (22)

- Domestic Constraints On The President Regarding Foreign PolicyDocument8 pagesDomestic Constraints On The President Regarding Foreign PolicyJason BrownNo ratings yet

- Liberty Index 2015Document15 pagesLiberty Index 2015Matthew Daniel NyeNo ratings yet

- NEW Research RD 1Document10 pagesNEW Research RD 1Jaywal16No ratings yet

- Posen and Ross 1997Document49 pagesPosen and Ross 1997Pedro MoltedoNo ratings yet

- 3429 PolDocument6 pages3429 PolPrakriti KohliNo ratings yet

- CapstoneroughdraftDocument14 pagesCapstoneroughdraftapi-349019084No ratings yet

- Expert Affidavit of Gary Segura, PH.D.: of Mass. v. U.S. Dep't of Health and Human Servs., No. 09-11156 (July 8, 2009)Document56 pagesExpert Affidavit of Gary Segura, PH.D.: of Mass. v. U.S. Dep't of Health and Human Servs., No. 09-11156 (July 8, 2009)Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- PoliticalPolarization v6 CB 11 23Document5 pagesPoliticalPolarization v6 CB 11 23Anastasia NavalyanaNo ratings yet

- U S Foreign Policy The Paradox of World Power 5Th Edition Hook Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument25 pagesU S Foreign Policy The Paradox of World Power 5Th Edition Hook Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFkennethmorgansjyfwondxp100% (7)

- Summary of In Trump We Trust: by Ann Coulter | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of In Trump We Trust: by Ann Coulter | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Levitz America Is Not A Center-Right Nation'Document5 pagesLevitz America Is Not A Center-Right Nation'michaelNo ratings yet

- Policy Review - February & March 2013, No. 177Document103 pagesPolicy Review - February & March 2013, No. 177Hoover Institution100% (1)

- True Blues: The Contentious Transformation of the Democratic PartyFrom EverandTrue Blues: The Contentious Transformation of the Democratic PartyNo ratings yet

- (American Govt and Politics) - Political Parties and ElectionsDocument15 pages(American Govt and Politics) - Political Parties and ElectionsTreblif AdarojemNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Gary M. Segura, PH.DDocument47 pagesAffidavit of Gary M. Segura, PH.DEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- реферат 2Document5 pagesреферат 2byy5w8vcj6No ratings yet

- Foreign Policy Index Vol. 5Document39 pagesForeign Policy Index Vol. 5AmberNich0leNo ratings yet

- Public Opinion Domestic Structure and Foreign PoliDocument30 pagesPublic Opinion Domestic Structure and Foreign PoliaanneNo ratings yet

- Running Head: POLITICAL IDEOLOGY 1: Current Events ReportDocument5 pagesRunning Head: POLITICAL IDEOLOGY 1: Current Events ReportDARIUS KIMINZANo ratings yet

- Faces of Power: Constancy and Change in United States Foreign Policy from Truman to ObamaFrom EverandFaces of Power: Constancy and Change in United States Foreign Policy from Truman to ObamaNo ratings yet

- 3 TrumpDocument10 pages3 TrumpRehmia ArshadNo ratings yet

- The Impostors: How Republicans Quit Governing and Seized American PoliticsFrom EverandThe Impostors: How Republicans Quit Governing and Seized American PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Kentucky Eckert Griffith Neg Kentucky Round4Document64 pagesKentucky Eckert Griffith Neg Kentucky Round4IanNo ratings yet

- Project 6 Signature AssignmentDocument9 pagesProject 6 Signature Assignmentapi-722214314No ratings yet

- FukuyMcFaul07 PDFDocument16 pagesFukuyMcFaul07 PDFassisyNo ratings yet

- Richard G. Lugar, Statesman of the Senate: Crafting Foreign Policy from Capitol HillFrom EverandRichard G. Lugar, Statesman of the Senate: Crafting Foreign Policy from Capitol HillNo ratings yet

- The Democratic PartyDocument6 pagesThe Democratic PartyIrina TacheNo ratings yet

- American Association For Public Opinion ResearchDocument1 pageAmerican Association For Public Opinion Researchwildguess1No ratings yet

- Uganda KonyDocument20 pagesUganda KonyAdriana AlarcónNo ratings yet

- American PoliticsDocument8 pagesAmerican Politicsogarivincent20No ratings yet

- Elections, Partisanship, and Policy Analysis:: A Conversation With Political Strategist Donnie FowlerDocument4 pagesElections, Partisanship, and Policy Analysis:: A Conversation With Political Strategist Donnie Fowlerjeffrey_bellisarioNo ratings yet

- Civic CultureDocument12 pagesCivic Culturemuhammad umarNo ratings yet

- Predicting the Presidency: The Potential of Persuasive LeadershipFrom EverandPredicting the Presidency: The Potential of Persuasive LeadershipNo ratings yet

- Valdai Paper #31: Another History (Story) of Latin AmericaDocument10 pagesValdai Paper #31: Another History (Story) of Latin AmericaValdai Discussion ClubNo ratings yet

- Geopolitical Economy: The Discipline of MultipolarityDocument12 pagesGeopolitical Economy: The Discipline of MultipolarityValdai Discussion ClubNo ratings yet

- Multilateralism A La Carte: The New World of Global GovernanceDocument8 pagesMultilateralism A La Carte: The New World of Global GovernanceValdai Discussion ClubNo ratings yet

- Valdai Paper #29: Mafia: The State and The Capitalist Economy. Competition or Convergence?Document12 pagesValdai Paper #29: Mafia: The State and The Capitalist Economy. Competition or Convergence?Valdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Reviving A Species. Why Russia Needs A Renaissance of Professional JournalismDocument7 pagesReviving A Species. Why Russia Needs A Renaissance of Professional JournalismValdai Discussion ClubNo ratings yet

- Valdai Paper #14: The G7 and The BRICS in The Post-Crimea World OrderDocument10 pagesValdai Paper #14: The G7 and The BRICS in The Post-Crimea World OrderValdai Discussion ClubNo ratings yet

- Toward The Great Ocean - 3: Creating Central EurasiaDocument28 pagesToward The Great Ocean - 3: Creating Central EurasiaValdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Marxism in The Post-Globalization EraDocument13 pagesMarxism in The Post-Globalization EraValdai Discussion ClubNo ratings yet

- CalendarDocument5 pagesCalendarGiles DayaNo ratings yet

- Security Sector Reform and Post-Conflict PeacebuildingDocument349 pagesSecurity Sector Reform and Post-Conflict PeacebuildingThayla ComercialNo ratings yet

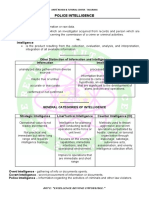

- Lea Police Intelligence FinalDocument9 pagesLea Police Intelligence FinalLloyd Rafael EstabilloNo ratings yet

- National Security and The Right To Information in Europe - April 2013Document61 pagesNational Security and The Right To Information in Europe - April 2013radu vasileNo ratings yet

- Con1 - Terror DADocument305 pagesCon1 - Terror DAEthan JacobsNo ratings yet

- Austrian Military RecordsDocument11 pagesAustrian Military RecordsJosh ChesnikNo ratings yet

- Visa Requirements For Chinese Citizens (Disambiguation)Document10 pagesVisa Requirements For Chinese Citizens (Disambiguation)yellowenglishNo ratings yet

- Fabrice ResumeDocument2 pagesFabrice Resumeapi-341965921No ratings yet

- 1974 SFOB SOP-2 by Darry D EgglestonDocument4 pages1974 SFOB SOP-2 by Darry D EgglestonChris WhiteheadNo ratings yet

- PCVL Brgy 1207016Document9 pagesPCVL Brgy 1207016Yes Tirol DumaganNo ratings yet

- MFR Nara - T1a - FBI - Doucet Phillip - 12-4-03 - 00407Document2 pagesMFR Nara - T1a - FBI - Doucet Phillip - 12-4-03 - 004079/11 Document ArchiveNo ratings yet

- List of Kargil War Heroes - Take A Moment To Remember Kargil Heroes PDFDocument5 pagesList of Kargil War Heroes - Take A Moment To Remember Kargil Heroes PDFspoorthiss100% (2)

- Cyber Safety PP Presentation For Class 11Document16 pagesCyber Safety PP Presentation For Class 11WAZ CHANNEL100% (1)

- Peran Indonesia Dalam Memerangi Terorisme PDFDocument18 pagesPeran Indonesia Dalam Memerangi Terorisme PDFCAHAYA NETNo ratings yet

- x349 Chess - Com AccountsDocument12 pagesx349 Chess - Com AccountsGrupa 44 - Razvan RoscaNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Students Numeracy Profile SY 2020-2021 Quarter: Pre-TestDocument2 pagesConsolidated Students Numeracy Profile SY 2020-2021 Quarter: Pre-TestRichard NinadaNo ratings yet

- The Morning Calm Korea Weekly - Oct. 8, 2004Document24 pagesThe Morning Calm Korea Weekly - Oct. 8, 2004Morning Calm Weekly NewspaperNo ratings yet