Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Web Revcache Review 32510

Uploaded by

api-234077090Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Web Revcache Review 32510

Uploaded by

api-234077090Copyright:

Available Formats

Tiffany M. Gill. Beauty Shop Politics: African American Womens Activism in the Beauty Industry.

Urbana: University

of Illinois Press, 2010. 208S. $75.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-252-03505-0; $25.00 (paper), ISBN 978-0-252-07696-1.

Reviewed by Joey Fink

Published on H-SAWH (November, 2011)

Commissioned by Antoinette G. van Zelm

Beautiful Hard Work: Black Beauticians at the Intersection of Labor, Beauty, Politics, and Freedom in

Twentieth-Century America

In Beauty Shop Politics, historian Tiffany M. Gill takes

readers from the turn-of-the-century golden age of black

business in America through the height of the black

freedom struggle to the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Along the way, she focuses on the experiences of

black beauticians and connects economic autonomy, entrepreneurship, and political activism within the black

beauty industry. Throughout the twentieth century, Gill

shows, African American beauticians used their unique

position within their communitieswhich offered them a

considerable degree of security and autonomy, as well as

intimate connections to their clientsto engage in racialuplift work, community organizing, and political mobilization. As Gill explains in her introduction, in the early

stages of her research, she was astonished to find everyone from Martin Luther King to Ella Baker touting

beauticians as key political mobilizers and set out to

understand how it was that beauty culturists figured

so prominently in national and grassroots political campaigns (p. 2). It was their economic autonomy, their ability to build and maintain close relationships within their

communities, and their reliance on a black clientele, Gill

concludes, that accounted for their significant political

activism. The salon was a conflation of home and work

that served as a gendered space of pampering and femininity, while it was also the site of grueling physical labor, calculated entrepreneurial pursuits, and savvy political and social activism. Black beauty culturists worked

within the space of the salon to promote opportunities

for black women, strengthen their communities, and advocate for civil rights.

beauty culture provided opportunities for black women

to develop into community leaders and political activists.

Gill mines memoirs, interviews, and archival sources,

such as the Negro World and the records of the National

Association of Colored Womens Clubs (NACWC), to

find the telling clues of black beauty culturists political

work and recover the histories of clubs, like the National

Beauty Culturists League (NBCL). In a tightly written

narrative that moves chronologically from the late 1800s

to 2007 in six chapters, Gill offers a fresh analysis of familiar early twentieth-century black businesswomen, including Madame C. J. Walker and Annie Turnbo Malone, and draws attention to the roots in the black beauty

industry shared by such well-known clubwomen and

civil rights organizers as Mamie Garvin Fields; Lucille

Green Randolph (wife of A. Philip Randolph); and Bernice Robinson (cousin of the renowned civil rights leader

Septima Clark).

Some of the strongest and most compelling parts

of Gills monograph, in fact, are when she offers minibiographies of black women in the beauty industry to

demonstrate the intersection of commercial pursuits and

social reform, as well as the connection between economic autonomy and political courage. Through the

story of Ezella Mathis Carter, a graduate of Spelman

Seminary in 1907 and later a beauty-culture student in

Chicago at the Enterprise Institute, we learn how educated clubwomen used door-to-door product demonstrations and sales to administer to the needs of poor

women, engage in race work, and advance entrepreneurially independent of the masculine world of black business. Close looks at Walkers economic activism and

Amy Jacques Garveys Our Women and What They

Think page of the Negro World reveal the ways in which

African Americans navigated the tensions between racefirst ideologies that chastised most modern black beauty

While other scholarship on the beauty industry has

highlighted how important it was for black women as

a means of employment, a gateway into modernity and

consumerism, and a part of the discourse on racial uplift and black pride, no one has yet looked at how black

1

H-Net Reviews

practices and a lucrative, autonomous industry that promoted economic nationalism and strategic philanthropy.

Building a narrative of Robinsons activism in South Carolina from a 1980 interview (conducted by Sue Thrasher

and Elliot Wiggington), Gill shows how the intersection of her economic necessity and political disappointments fueled the groundbreaking path that her life was

soon to take (p. 111). Robinson used her beauty salon in Charleston to hold voter registration drives and

strategy sessions. Because of her efforts, membership in

the National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People (NAACP) in Charleston rose from three hundred

to more than one thousand. Beautifully written, these

womens stories not only recover the lives of previously

invisible activists and entrepreneurs, but also provide a

window onto the beauty salon as a site of safety and empowerment where black beauticians, enjoying economic

autonomy and job security, could engage in subversive

political work (p. 106).

Gills analysis of the space of the beauty salon represents an important contribution to the historiography of

the African American freedom struggle. She shows how

black beauticians throughout the twentieth century occupied a particular space in the black community that

supported their activism. As arbiters of respectability

and style, and as laborers engaged in intimate, individualcare work, they often commanded a significant degree

of respect and trust. Moreover, individuals who owned

their own salons or worked hair in black homes, in addition to being free from the reprisals of white employers

or clients, could offer a safe space to disseminate information; register voters; spread and receive local news;

and (quite literally) hold an audience captive to informal

lectures on political rights, public health, and local resources. Vera Pigee of Clarksdale, Mississippi, was responsible for registering more than one hundred voters

through her beauty shop. When Clarksdales chief of police demanded that Pigee divulge the names of her clients,

she told him in no uncertain terms she would not, and

suggested he leave her shop, adding, If I ever need your

service I will call you (p. 119). Little wonder, then,

that Highlander Folk School founder Myles Horton recognized the importance of developing black beauticians

as leaders in the civil rights struggle.

Not every beauty salon functioned as a site of subversive political activity, Gill notes, and not every black

beauty culturist engaged in political organizing through

their entrepreneurship and labor. Yet this acknowledgement leads readers to consider an even more exciting intervention that Beauty Shop Politics offers: a reevaluation

of the meaning and importance of beauty work itself. The

ability to gather safely and freely and the sense of having ones dignity restored through professional care and

attention is itself a political act (p. 136). Gill deftly

weaves together personal narratives, an analysis of space

and community, and evocative reminiscences to demonstrate how a seemingly simple act like having ones hair

washed can carry so much emotional and psychological

weight. Take, for instance, the reference to beauty culture that Gill finds in Anne Moodys memoir Coming of

Age in Mississippi (1968). After enduring the invectives

and food hurled at her during a Woolworth sit-in in 1964,

Moody sought refuge and respite in a beauty shop across

the street from the NAACP office, where several clients

gladly let her go ahead of them. Indeed, Gill writes,

beauty salons, particularly those in the Jim Crow South,

functioned as asylums for black women ravaged by the

effects of segregation and served as incubators for black

womens leadership and platforms from which to agitate

for social and political change (p. 99).

In the years since the 1960s, desegregation and opportunities within the white-collar sector for African Americans, along with increased female attendance in vocational schools and universities, have forced the black

beauty industry into a different, sometimes obsolete

role (p. 125). These changes, Gill stresses, do not preclude political activism, and her focus on the connections between black beauty culture since the 1970s and

the black womens health movement undermines a strict

declension narrative of post-civil rights African American activism. Indeed, as Gill points out, the health

risks that black women face disproportionately to white

womencardiovascular disease, diabetes, breast cancer,

and HIV/AIDSare all the more dire in the former Jim

Crow states, highlighting the entrenched, institutionalized, and pervasive racial inequalities that belie any notion of a post-racial America. Black beauticians in the

late twentieth century, like the generations before them,

used their salons, labor, knowledge, and community connections to promote the dignity and care of the black female body.

It is perhaps because Gills analysis and writing are

so compelling in the first and last thirds of her monograph that the middle sectiona discussion of the international presence of black beauticiansseems sparse and

underdeveloped. Gill packs a lot into 136 pages. The

books reasonable length and clear, consistent argument,

however, make it ideal for advanced undergraduates and

first-year graduate students. The fifth chapter on black

beauticians and the black freedom struggle is perhaps

the strongest and most engaging; it could stand alone

as a short reading. Indeed, with its fresh analysis of

2

H-Net Reviews

black womens political engagement with race work, entrepreneurship, and the freedom struggle, Beauty Shop

Politics represents some of the most exciting new work on

twentieth-century American history, bridging African

American history, womens history, and labor and business history, while keeping African American women

still underrepresented in both the historical record and

scholarly studiesfront and center.

If there is additional discussion of this review, you may access it through the list discussion logs at:

http://h-net.msu.edu/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl.

Citation: Joey Fink. Review of Gill, Tiffany M., Beauty Shop Politics: African American Womens Activism in the

Beauty Industry. H-SAWH, H-Net Reviews. November, 2011.

URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=32510

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoncommercialNo Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- 8 EstagesofchangeDocument7 pages8 Estagesofchangeapi-234077090No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Social Stories 1Document23 pagesSocial Stories 1api-472451946No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Woman To Woman - Titus 2 MinistryDocument7 pagesWoman To Woman - Titus 2 Ministryapi-234077090100% (2)

- Confined Space: Hole Watch TrainingDocument36 pagesConfined Space: Hole Watch TrainingMalik JunaidNo ratings yet

- AnxolamDocument38 pagesAnxolammanjitdeshmukh2No ratings yet

- SbarDocument3 pagesSbarCharlie65129No ratings yet

- Discussion American DenialDocument18 pagesDiscussion American Denialapi-234077090No ratings yet

- Gail Mccabe ThesisDocument252 pagesGail Mccabe Thesisapi-234077090No ratings yet

- Schoolcharts2015 Updated0415Document10 pagesSchoolcharts2015 Updated0415api-234077090No ratings yet

- TheodicyDocument4 pagesTheodicyapi-234077090No ratings yet

- Kitchen CompanionDocument27 pagesKitchen CompanionfullquiverfarmNo ratings yet

- CarneyDocument24 pagesCarneyapi-234077090No ratings yet

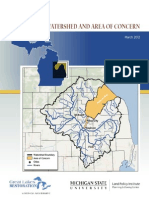

- Saginaw Bay Watershed and Aoc Handout WebDocument12 pagesSaginaw Bay Watershed and Aoc Handout Webapi-234077090No ratings yet

- RockoffwizardofozDocument16 pagesRockoffwizardofozapi-234077090No ratings yet

- Unit 6 62 Mustapha Tettey Addy Ghana Agbekor DanceDocument6 pagesUnit 6 62 Mustapha Tettey Addy Ghana Agbekor Danceapi-234077090No ratings yet

- HowtopantryDocument21 pagesHowtopantryapi-234077090No ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Screen - Dub DiolDocument4 pagesAntimicrobial Screen - Dub DiolNgân BảoNo ratings yet

- Helicobacter Pylori (PDFDrive)Document532 pagesHelicobacter Pylori (PDFDrive)Susacande López GirónNo ratings yet

- REFERAT Koass Neurologi - Carpal Tunnel SyndromeDocument34 pagesREFERAT Koass Neurologi - Carpal Tunnel SyndromeVindhita RatiputriNo ratings yet

- Swine FluDocument4 pagesSwine FluNader Smadi100% (2)

- Vasculitis SyndromesDocument56 pagesVasculitis SyndromesHengki Permana PutraNo ratings yet

- Curie Breakthrough by SlidesgoDocument47 pagesCurie Breakthrough by SlidesgoRai YugiNo ratings yet

- Rahul Hospital ReportDocument24 pagesRahul Hospital ReportHritik Chaubey100% (1)

- J. Nat. Prod., 1994, 57 (4), 518-520Document4 pagesJ. Nat. Prod., 1994, 57 (4), 518-520Casca RMNo ratings yet

- Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL)Document11 pagesNon-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL)archanaNo ratings yet

- Architectural Ideas For The New NormalDocument4 pagesArchitectural Ideas For The New NormalChi De LeonNo ratings yet

- Revised ThesisDocument51 pagesRevised ThesisOfficial Lara Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- The Merciad, April 14, 1988Document8 pagesThe Merciad, April 14, 1988TheMerciadNo ratings yet

- CF 756Document100 pagesCF 756Manoj KumarNo ratings yet

- Discharge Plan Post SeizureDocument2 pagesDischarge Plan Post SeizureVecky TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Healthmedicinet Com II 2014 AugDocument400 pagesHealthmedicinet Com II 2014 AugHeal ThmedicinetNo ratings yet

- Cavite State University: The Fire Safety Measures of Informal Settlers in Barangay Niog 1 Bacoor, Cavite"Document9 pagesCavite State University: The Fire Safety Measures of Informal Settlers in Barangay Niog 1 Bacoor, Cavite"Ralph Joshua BedraNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology For Health Sciences BHS415: Rozzana Mohd Said, PHDDocument20 pagesPathophysiology For Health Sciences BHS415: Rozzana Mohd Said, PHDatiqullah tarmiziNo ratings yet

- Work CitedDocument5 pagesWork Citedapi-317144934No ratings yet

- Makalah Mkdu Bahasa InggrisDocument2 pagesMakalah Mkdu Bahasa Inggrisfadhilah anggrainiNo ratings yet

- Nephrotic Syndrome: DR Thuvaraka WareDocument5 pagesNephrotic Syndrome: DR Thuvaraka Warechloe1411No ratings yet

- VPHin IndiaoieproofDocument17 pagesVPHin Indiaoieproofhari prasadNo ratings yet

- Black SigatokaDocument2 pagesBlack SigatokaLALUKISNo ratings yet

- 10 Simulation Exercises As A Patient Safety Strategy PDFDocument9 pages10 Simulation Exercises As A Patient Safety Strategy PDFAmanda DavisNo ratings yet

- Dental Form 1 - 042718R3Document4 pagesDental Form 1 - 042718R3JohnNo ratings yet

- Vampires and Death in New England, 1784 To 1892Document17 pagesVampires and Death in New England, 1784 To 1892Ferencz IozsefNo ratings yet

- Gender ReassignmentDocument4 pagesGender ReassignmentDaphne Susana PaulinNo ratings yet