Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Crim Pro Cases

Uploaded by

Faith Imee RobleCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Crim Pro Cases

Uploaded by

Faith Imee RobleCopyright:

Available Formats

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

Espino v. People [G.R. No. 188217. July 3, 2013.]

Bacasmas v. Sandiganbayan [G.R. No. 189343. July 10, 2013.]

Coscolluela v. Sandiganbayan [G.R. No. 191411. July 15, 2013.]

People v. Odtuhan [G.R. No. 191566, July 17, 2013.]

Jose v. Suarez [G.R. No. 176111. July 17, 2013.]

Avelino y Bulawan v. People [G.R. 181444. July 17, 2013.]

People v. Marvin Cruz [G.R. 201728. July 17, 2013.]

Anita Mangila v. Judge Pangilinan et.al. [G.R. 160739. July 17, 2013.]

People v. Victorino Reyes [G.R. 173307. July 17, 2013.]

People v. Clara [GR No. 195528. July 24, 2013.]

People v. Roman [G.R. No. 198110. July 31, 2013.]

Lihaylihay and Vinluan v. People [G.R. No. 191219. July 31, 2013.]

Lee v. Lee [GR No. 181658. August 7, 2013.]

Chavez v. Fria [GR No. 183014. August 7, 2013.]

Neri v. Sandiganbayan [GR No. 202243. August 7, 2013.]

Hasegawa v. Giron [G.R. No. 184536, August 14, 2013.]

People v. Pepino-Consulta [G.R. No. 191071. Aug. 28, 2013.]

People v. Amistoso y Broca [G.R. No. 201447. August 28, 2013.]

Republic (PCGG) v. Bakunawa [G.R. NO. 180418, AUGUST 28, 2013.]

People v. Manalili y Jose [G.R. No. 191253. August 28, 2013.]

Punzalan v. Plata [G.R. No. 160316. September 02, 2013.]

Kummer v. People [G.R. No. 174461, September 11, 2013.]

Disini v. Sandiganbayan [G.R. 169823-24/174764-65. September 11, 2013.]

People v. De Los Reyes [G.R. No. 197550. September 25, 2013.]

Singian vs. Sandiganbayan [G.R. Nos.195011-19. September 30, 2013.]

Chua v. Executive Judge-MTC Manila [G.R. No. 202920. October 2, 2013.]

Ramirez v. People [G.R. No. 197832. October 2, 2013.]

People v. Cuaycong [G.R. No. 196051. October 2, 2013.]

Carbajosa v. Judge Patricio [A.M. No. MTJ-13-1834. October 02, 2013.]

Jadewell Parking v. Judge Lidua Sr. [G.R. No. 169588. October 7, 2013.]

People v. Dizon [G.R. No. 199901. October 9, 2013.]

People v. Galicia [G.R. No. 191063. October 9, 2013.]

People v. de Jesus y Mendoza [G.R. No. 190622. October 7, 2013.]

People v. Hadji Socor Candidia [G.R. No. 191263. October 16, 2013.]

People v. Jose y Lagua [G.R. No. 200053. October 23, 2013.]

Century Chinese v. Ling Na Lau [G.R. No. 188526. November 11, 2013.]

People v. Castillo y Alignay [G.R. No. 190180. November 27, 2013.]

People v. Roberto Velasco [G.R. No. 190318. November 27, 2013.]

People vs. Montevirgen [G.R. No. 189840. December 11, 2013.]

Antiquera y Codes v. People [G.R. No. 180661. December 11, 2013.]

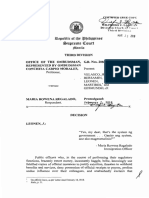

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

Espino v. People [G.R. No. 188217. July 3, 2013]

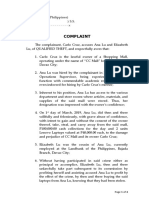

FACTS:

Accused- Espino, being then the Senior Sales Executive of the complainant Kuehne and Nagel Inc. herein represented by

Honesto Raquipiso, tasked with liasoning with the import coordinators of the complainants various clients including the

delivery of their commissions, said accused received in trust from the complainant Metrobank check no. 1640443816 in the

amount of P12,675.00 payable to Mr. Florante Banaag, import coordinator of Europlay, with the obligation to deliver the

same but said accused failed to deliver said check in the amount of P12,675.00 and instead, once in possession of the same,

forged the signature of Mr. Banaag and had the check rediscounted and far from complying with his obligation, despite

demands to account and/or remit the same, with unfaithfulness and/or abuse of confidence, did then and there willfully,

unlawfully and feloniously misappropriate, misapply and convert the proceeds thereof to his own personal use and benefit,

to the damage and prejudice of the said complainant, in the amount of P12,675.00.39

On 14 October 2002, the Fiscals Office of Paranaque charged the accused with six (6) counts of estafa under Article 315,

paragraph 1(b) for allegedly rediscounting checks that were meant to be paid to the companys import coordinators.

Upon trial, accused in his testimony claimed that what precipitated the charges was his employers discontent after he had

allegedly lost an account for the company. He was eventually forced to resign and upon submission of the resignation, was

asked to sign a sheet of paper that only had numbers written on it. He complied with these demands under duress, as

pressure was exerted upon him by complainants and later on filed a case for illegal dismissal,in which he denied having

forged the signature of Mr. Banaag at the dorsal portion of the checks.

RTC convicted the accused of Estafa under article 315 paragraph 2a. In response, he filed a Motion for

Reconsideration, arguing that the trial court committed a grave error in convicting him of estafa under paragraph 2(a),

which was different from paragraph 1(b) of Article 315 under which he had been charged. He also alleged that there was no

evidence to support his conviction. Thus, he contended that his right to due process of law was thereby violated. RTC

Denied the motion, CA also denied his appeal, stating that the alleged facts sufficiently comprise the elements of estafa as

enumerated in Article 315, paragraph 2(a).25 His subsequent Motion for Reconsideration was likewise dismissed.

Accused filed petition for Review under rule 45. Specifically claiming that he was denied due process when he was

convicted of estafa under Article 315, paragraph 2(a) of the Revised Penal Code (RPC) despite being charged with estafa

under Article 315, paragraph 1(b)

ISSUE/s:

WON a conviction for estafa under a different paragraph from the one charged is legally permissible.

HELD:

Article 3, Section 14, paragraph 2 of the 1987 Constitution, requires the accused to be "informed of the nature and cause of

the accusation against him" in order to adequately and responsively prepare his defense. The prosecutor is not required,

however, to be absolutely accurate in designating the offense by its formal name in the law. As explained by the Court in

People v. Manalili:

It is hornbook doctrine, however, that "what determines the real nature and cause of the accusation against an accused is

the actual recital of facts stated in the information or complaint and not the caption or preamble of the information or

1|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

complaint nor the specification of the provision of law alleged to have been violated, they being conclusions of law."

This doctrine negates the due process argument of the accused, because he was sufficiently apprised of the facts that

pertained to the charge and conviction for estafa.

First, while the fiscal mentioned Article 315 and specified paragraph 1(b), the controlling words of the Information are

found in its body. Accordingly, the Court explained the doctrine in Flores v. Layosa as follows:

The Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure provides that an information shall be deemed sufficient if it states, among others,

the designation of the offense given by the statute and the acts of omissions complained of as constituting the offense.

However, the Court has clarified in several cases that the designation of the offense, by making reference to the section or

subsection of the statute punishing, it [sic] is not controlling; what actually determines the nature and character of the crime

charged are the facts alleged in the information. The Courts ruling in U.S. v. Lim San is instructive:

Notwithstanding the apparent contradiction between caption and body, we believe that we ought to say and hold that the

characterization of the crime by the fiscal in the caption of the information is immaterial and purposeless, and that the facts

stated in the body of the pleading must determine the crime of which the defendant stands charged and for which he must

be tried. The establishment of this doctrine is permitted by the Code of Criminal Procedure, and is thoroughly in accord

with common sense and with the requirements of plain justice

From a legal point of view, and in a very real sense, it is of no concern to the accused what is the technical name of the

crime of which he stands charged. It in no way aids him in a defense on the merits. Whatever its purpose may be, its result

is to enable the accused to vex the court and embarrass the administration of justice by setting up the technical defense that

the crime set forth in the body of the information and proved in the trial is not the crime characterized by the fiscal in the

caption of the information. That to which his attention should be directed, and in which he, above all things else, should be

most interested, are the facts alleged. The real question is not did he commit a crime given in the law some technical and

specific name, but did he perform the acts alleged in the body of the information in the manner therein set forth. If he did, it

is of no consequence to him, either as a matter of procedure or of substantive right, how the law denominates the crime

which those acts constitute. The designation of the crime by name in the caption of the information from the facts alleged

in the body of that pleading is a conclusion of law made by the fiscal. In the designation of the crime the accused never has

a real interest until the trial has ended. For his full and complete defense he need not know the name of the crime at all. It is

of no consequence whatever for the protection of his substantial rights... If he performed the acts alleged, in the manner,

stated, the law determines what the name of the crime is and fixes the penalty therefore. It is the province of the court alone

to say what the crime is or what it is named.

The above discussion leads to the conclusion that the Information in this case may be interpreted as charging the accused

with both estafa under paragraph 1 (b) and estafa under paragraph 2(a). It is a basic and fundamental principle of criminal

law that one act can give rise to two offenses,41 all the more when a single offense has multiple modes of commission.

Hence, the present Petition cannot withstand the tests for review as provided by jurisprudential precedent. While the

designation of the circumstances attending the conviction for estafa could have been more precise, there is no reason for

this Court to review the findings when both the appellate and the trial courts agree on the facts. We therefore adopt the

factual findings of the lower courts in totality, bearing in mind the credence lent to their appreciation of the evidence.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant Petition is hereby DENIED. The assailed Decision dated 24 February

2009 and Resolution dated 25 May 2009 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CR. No. 31106 are AFFIRMED.SO

ORDERED.

2|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

Bacasmas v. Sandiganbayan [G.R. No. 189343. July 10, 2013.]

FACTS:

ALAN C. GAVIOLA, EUSTAQUIO B. CESA, BENILDA N. BACASMAS and EDNA J. JACA, public officers, being

then the City Administrator, City Treasurer, Cash Division Chief and City Accountant, respectively, of the Cebu City

Government are accused of violating Section 3 (e) of R.A. commonly involving willful, intentional, and conscious acts or

omissions when there is a duty to act on the part of the public official or employee.

The Sandiganbayan held that the accused were all guilty of gross inexcusable negligence. Claiming that it was the practice

in their office, they admittedly disregarded the observance of the law and COA rules and regulations on the approval and

grant of cash advances. The anti-graft court also stated that the undue injury to the government was unquestionable because

of the shortage amounting to P9,810,752.60.

Gaviola, Cesa, Bacasmas, and Jaca individually filed their Motions for Reconsideration of the 7 May 2009 Decision. Their

motions impugned the sufficiency of the Information and the finding of gross inexcusable negligence, undue injury, and

unwarranted benefit.

The Sandiganbayan, in a Resolution promulgated 27 August 2009 denied the Motions for Reconsideration of the accused.

It ruled that the Information was sufficient, because the three modes of violating Section 3 (e) of R.A. 3019 commonly

involved willful, intentional, and conscious acts or omissions when there is a duty to act on the part of the public official or

employee. Furthermore, the three modes may all be alleged in one Information.

ISSUE/S:

Whether the Information was sufficient.

HELD:

An information is deemed sufficient if it contains the following: (a) the name of all the accused; (b) the designation of the

offense as given in the statute; (c) the acts or omissions complained of as constituting the offense; (d) the name of the

offended party; (e) the approximate date of the commission of the offense; and (f) the place where the offense was

committed. c

The Information is sufficient, because it adequately describes the nature and cause of the accusation against

petitioners, namely the violation of the aforementioned law. The use of the three phrases "manifest partiality," "evident

bad faith" and "inexcusable negligence" in the same Information does not mean that three distinct offenses were thereby

charged but only implied that the offense charged may have been committed through any of the modes provided by the

law. In addition, there was no inconsistency in alleging both the presence of conspiracy and gross inexcusable negligence,

because the latter was not simple negligence. Rather, the negligence involved a willful, intentional, and conscious

indifference to the consequences of one's actions or omissions.

Coscolluela v. Sandiganbayan [G.R. No. 191411. July 15, 2013.]

FACTS:

Coscolluela was governor of the Province of Negros Occidental (Province) which ended on June 30, 2001. During his

tenure, Nacionales served as his Special Projects Division Head, Amugod as Nacionales' subordinate, and Malvas as

Provincial Health Officer. The Office of the Ombudsman for the Visayas received a letter-complaint requesting for

assistance to investigate the anomalous purchase of medical and agricultural equipment which allegedly happened around a

month before Coscolluela stepped down from office.

3|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

A Final Evaluation Report was issued which upgraded the complaint into a criminal case against petitioners. On March 27,

2003, the assigned Graft Investigation Officer Butch E. Caares (Caares) prepared a Resolution (March 27, 2003

Resolution), finding probable cause against petitioners for violation of Section 3 (e) of Republic Act No. (RA) 3019,

otherwise known as the "Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act," and recommended the filing of the corresponding

information. On even date, the Information was prepared and signed by Caares and submitted to Deputy Ombudsman for

the Visayas Primo C. Miro (Miro) for recommendation. Miro recommended the approval of the Information on June 5,

2003. However, the final approval of Acting Ombudsman Orlando C. Casimiro (Casimiro), came only on May 21, 2009,

and on June 19, 2009, the Information was filed before the SB.

Petitioners alleged that they learned about the March 27, 2003 Resolution and Information only when they received a copy

of the latter shortly after its filing with the SB.

On July 9, 2009, Coscolluela filed a Motion to Quash, arguing, among others, that his constitutional right to speedy

disposition of cases was violated as the criminal charges against him were resolved only after almost eight (8) years since

the complaint was instituted. Nacionales, Malvas, and Amugod later adopted Coscolluela's motion. In reply, the

respondents filed their Opposition explaining that although the Information was originally dated March 27, 2003, it still

had to go through careful review and revision before its final approval. It also pointed out that petitioners never raised any

objections regarding the purported delay in the proceedings during the interim. The Sandiganbayan denied their Motion to

Quash for lack of merit as well as their respective Motions for Reconsideration.

ISSUE/S:

Whether the SB gravely abused its discretion in finding that petitioners' right to speedy disposition of cases was not

violated.

HELD:

A person's right to the speedy disposition of his case is guaranteed under Section 16, Article III of the 1987 Philippine

Constitution (Constitution) which provides:

SEC. 16.All persons shall have the right to a speedy disposition of their cases before all judicial, quasi-judicial, or

administrative bodies.

Jurisprudence dictates that the right is deemed violated only when the proceedings are attended by vexatious, capricious,

and oppressive delays; or when unjustified postponements of the trial are asked for and secured; or even without cause or

justifiable motive, a long period of time is allowed to elapse without the party having his case tried. The following factors

may be considered and balanced: (1) the length of delay; (2) the reasons for the delay; (3) the assertion or failure to assert

such right by the accused; and (4) the prejudice caused by the delay.

The Court holds that petitioners' right to a speedy disposition of their criminal case had been violated.

First, it is observed that the preliminary investigation proceedings took a protracted amount of time to complete.

Section 4, Rule II of the Administrative Order No. 07 dated April 10, 1990, otherwise known as the "Rules of Procedure of

the Office of the Ombudsman," reveals that there is no complete resolution of a case under preliminary investigation until

the Ombudsman approves the investigating officer's recommendation to either file an Information with the SB or to dismiss

the complaint. Therefore, in the case at bar, the preliminary investigation proceedings against the petitioners were not

terminated upon Caares' preparation of the March 27, 2003 Resolution and Information but rather, only at the time

4|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

Casimiro finally approved the same for filing with the SB. In this regard, the proceedings were terminated only on May 21,

2009, or almost eight (8) years after the filing of the complaint.

Second, the above-discussed delay in the Ombudsman's resolution of the case largely remains unjustified.

Verily, the Office of the Ombudsman was created under the mantle of the Constitution, mandated to be the "protector of

the people" and has the inherent duty not only to carefully go through the particulars of case but also to resolve the same

within the proper length of time. Its dutiful performance should not only be gauged by the quality of the assessment but

also by the reasonable promptness of its dispensation.

Third, the Court deems that petitioners cannot be faulted for their alleged failure to assert their right to speedy disposition

of cases.

They were only informed of the March 27, 2003 Resolution and Information against them only after the lapse of six (6)

long years, or when they received a copy of the latter after its filing with the SB on June 19, 2009. In this regard, they

could have reasonably assumed that the proceedings against them have already been terminated. This serves as a plausible

reason as to why petitioners never followed-up on the case altogether. Being the respondents in the preliminary

investigation proceedings, it was not the petitioners' duty to follow up on the prosecution of their case. Conversely, it was

the Office of the Ombudsman's responsibility to expedite the same within the bounds of reasonable timeliness in view of its

mandate to promptly act on all complaints lodged before it.

Fourth, the Court finally recognizes the prejudice caused to the petitioners by the lengthy delay in the proceedings against

them.

Akin to the right to speedy trial, its "salutary objective" is to assure that an innocent person may be free from the anxiety

and expense of litigation or, if otherwise, of having his guilt determined within the shortest possible time compatible with

the presentation and consideration of whatsoever legitimate defense he may interpose. This looming unrest as well as the

tactical disadvantages carried by the passage of time should be weighed against the State and in favor of the individual. For

the SB's patent and utter disregard of the existing laws and jurisprudence surrounding the matter, the Court finds that it

gravely abused its discretion when it denied the quashal of the Information. Perforce, the assailed resolutions must be set

aside and the criminal case against petitioners be dismissed.

While the foregoing pronouncement should, as matter of course, result in the acquittal of the petitioners, it does not

necessarily follow that petitioners are entirely exculpated from any civil liability, assuming that the same is proven in a

subsequent case which the Province may opt to pursue.

Section 2, Rule 111 of the Rules of Court provides that an acquittal in a criminal case does not bar the private offended

party from pursuing a subsequent civil case based on the delict, unless the judgment of acquittal explicitly declares that

the act or omission from which the civil liability may arise did not exist. As explained in the case of Abejuela v.

People, citing Banal v. Tadeo, Jr.:

The Rules provide: "The extinction of the penal action does not carry with it extinction of the civil, unless the

extinction proceeds from a declaration in a final judgment that the fact from which the civil might arise did not

exist. In other cases, the person entitled to the civil action may institute it in the jurisdiction and in the manner

provided by law against the person who may be liable for restitution of the thing and reparation or indemnity for

the damage suffered."

5|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

xxx xxx xxx

In Banal vs. Tadeo, Jr., we declared:

"While an act or omission is felonious because it is punishable by law, it gives rise to civil liability not so much because it

is a crime but because it caused damage to another. Viewing things pragmatically, we can readily see that what gives rise

to the civil liability is really the obligation and moral duty of everyone to repair or make whole the damage caused

to another by reason of his own act or omission, done intentionally or negligently, whether or not the same be

punishable by law." (Emphasis and underscoring supplied)

Based on the violation of petitioners' right to speedy disposition of cases as herein discussed, the present case stands to be

dismissed even before either the prosecution or the defense has been given the chance to present any evidence. Thus, the

Court is unable to make a definite pronouncement as to whether petitioners indeed committed the acts or omissions from

which any civil liability on their part might arise as prescribed under Section 2, Rule 120 of the Rules of Court.

Consequently, absent this pronouncement, the Province is not precluded from instituting a subsequent civil case based on

the delict if only to recover the amount of P20,000,000.00 in public funds attributable to petitioners' alleged malfeasance.

People v. Odtuhan [G.R. No. 191566, July 17, 2013.]

FACTS:

On July 2, 1980, respondent married Jasmin Modina (Modina). On October 28, 1993, respondent married Eleanor A.

Alagon (Alagon). Sometime in August 1994, he filed a petition for annulment of his marriage with Modina. On February

23, 1999, the RTC of Pasig City, Branch 70 granted respondent's petition and declared his marriage with Modina void ab

initio for lack of a valid marriage license. On November 10, 2003, Alagon died.

In the meantime, in June 2003, private complainant Evelyn Abesamis Alagon learned of respondent's previous marriage

with Modina. She thus filed a Complaint-Affidavit charging respondent with Bigamy.

On February 5, 2008, Respondent moved for the quashal of the information on two grounds, to wit: (1) that the facts do not

charge the offense of bigamy; and (2) that the criminal action or liability has been extinguished. RTC Denied the motion.

Aggrieved, respondent instituted a special civil action on certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court before the Court of

Appeals and for which said court granted.

ISSUE/S:

WON the grant of Motion to Quash by Court of Appeals proper.

HELD:

As defined in Antone, "a motion to quash information is the mode by which an accused assails the validity of a criminal

complaint or information filed against him for insufficiency on its face in point of law, or for defects which are apparent in

the face of the information." It is a hypothetical admission of the facts alleged in the information. The fundamental test in

determining the sufficiency of the material averments in an Information is whether or not the facts alleged therein, which

are hypothetically admitted, would establish the essential elements of the crime defined by law. Evidence aliunde or

matters extrinsic of the information are not to be considered. To be sure, a motion to quash should be based on a defect in

the information which is evident on its fact. Thus, if the defect can be cured by amendment or if it is based on the ground

6|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

that the facts charged do not constitute an offense, the prosecution is given by the court the opportunity to correct the defect

by amendment. If the motion to quash is sustained, the court may order that another complaint or information be

filed except when the information is quashed on the ground of extinction of criminal liability or double jeopardy.

An examination of the information filed against respondent, however, shows the sufficiency of the allegations therein to

constitute the crime of bigamy as it contained all the elements of the crime as provided for in Article 349 of the Revised

Penal Code.

Thus, as held in Antone:

To conclude, the issue on the declaration of nullity of the marriage between petitioner and respondent only after the latter

contracted the subsequent marriage is, therefore, immaterial for the purpose of establishing that the facts alleged in the

information for Bigamy does not constitute an offense. Following the same rationale, neither may such defense be

interposed by the respondent in his motion to quash by way of exception to the established rule that facts contrary to the

allegations in the information are matters of defense which may be raised only during the presentation of evidence.

Jose v. Suarez [G.R. No. 176111. July 17, 2013.]

FACTS:

Carolina filed two Affidavit-Complaints for estafa against Purita before the Office of the City Prosecutor of Cebu, one

concerning 14 Chinabank checks totalling P1.5 million and the other pertaining to 10 Chinabank checks in the aggregate

amount of P2.1 million. However, the checks were dishonored upon presentment. Hence, the complaint for estafa.

In her two Counter-Affidavits, Purita claimed that her transactions with Carolina are civil in nature; they are mere loans

and the checks were issued only to guarantee payment.

In a Joint Resolution dated December 7, 2004, the City Prosecutor found probable cause to indict Purita for estafa. The

corresponding Information was filed against her.

Stressing that her transactions with Carolina did not constitute estafa, Purita promptly filed a Petition for Review before the

Department of Justice (DOJ). THAICD

The DOJ found merit in Purita's Petition for Review. It ruled that the transactions between Purita and Carolina do not

constitute estafa and are merely contracts of loan because Carolina was not deceived into parting with her money. On the

contrary, Carolina parted with her money on the expectation of earning interest from the transactions. Hence, the DOJ

reversed and set aside the Joint Resolution of the City Prosecutor in its July 5, 2005 Resolution Carolina moved for

reconsideration but was denied in a Resolution dated October 27, 2005.

Thus, pursuant to the DOJ's directive, City Prosecutor Nicolas C. Sellon moved for the withdrawal of the

Information before the RTC.

RTC, in its December 9, 2005 Order, denied the motion by simple stating that the motion in unmeritorious.

The CA ruled that the RTC Judge failed to personally assess or evaluate the Resolution of the DOJ. The December 9, 2005

Order of the RTC merely stated that the motion to withdraw was 'unmeritorious' while the March 10, 2006 Order only

declared that Purita's defense was 'a matter that must be addressed to the trial court'.||

7|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

ISSUE/S:

WON RTC gravely abused its discretion in denying the Motion to Withdraw Information without stating its reason for the

denial.

HELD:

The RTC failed to make its independent evaluation of the merits of the case when it denied the Prosecutor's Motion to

Withdraw Information.

When a trial court is confronted to rule on "a motion to dismiss a case or to withdraw an Information", it is its "bounden

duty to assess independently the merits of the motion, and this assessment must be embodied in a written order disposing

of the motion."

Avelino y Bulawan v. People [G.R. 181444. July 17, 2013.]

FACTS:

At around two in the afternoon at the Baseco Compound, Tondo, Manila, Chairman Hispano was gunned down by three

men wearing bonnets. Manalangsang, who was in a tricycle which was at the scene, and a Mary Ann Canada, was able to

recognize Bobby Avelino as one of the gunmen. During the trial testimonies of PO2 Galang, Bantiling and SOCO PSI

Cabamongan were presented in favor of Avelino. Avelino contended that he was at the LTO of Pasay City when the

incident happened. RTC found Avelino guilty of the crime of murder qualified by treachery and the CA upheld the said

decision as well.

ISSUE/S:

1.

Does the defense of denial and alibi prevail over the witness positive identification of the accused-appellants?

2. Was the expert opinion of SOCO PSI Cabamongan, who was considered as ordinary witness, rightfully determined by

the CA as immaterial?

HELD:

1. NO. According to the Supreme Court, for denial or alibi to prosper, it is not enough to prove that appellant was

somewhere else when the crime was committed; he must also demonstrate that it was physically impossible for him to have

been at the scene of the crime at the time of its commission. Unless substantiated by clear and convincing proof, such

defense is negative, self-serving, and undeserving of any weight in law. Denial, like alibi, as an exonerating justification, is

inherently weak and if uncorroborated regresses to blatant impotence. Like alibi, it also constitutes self-serving negative

evidence which cannot be accorded greater evidentiary weight than the declaration of credible witnesses who testify on

affirmative matters. Pharaoh Hotel, where petitioner claims to have stayed with his wife at the time of the commission of

the crime, is in Sta. Cruz, Manila is not far from the scene of the crime, which is in Baseco Compound in Tondo, Manila.

Indeed, for the defense of alibi to prosper, the accused must prove (a) that he was present at another place at the time of the

perpetration of the crime, and (b) that it was physically impossible for him to be at the scene of the crime. These, the

defense failed to do.

2. Yes. SC held that expert evidence is admissible only if: (a) the matter to be testified to is one that requires expertise, and

(b) the witness has been qualified as an expert. In this case, counsel for the petitioner failed to make the necessary

8|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

qualification upon presenting Cabamongan during trial. In the case, the defense failed to provide the qualifications needed

for him to be of such.

People v. Marvin Cruz [G.R. 201728. July 17, 2013.]

FACTS:

Marvin Cruz was filed with three criminal cases of rape. The victim was one of AAA, a minor of 17 years old. They got to

know each other through the exchange of text messages which then eventually led to a relationship. The victim said that

she consented with the relationship because Cruz told her that he was dying of leukemia. The prosecution contended that

she was forced by Cruz on the three separate incidents, and presented the following pieces of evidence:

(1)

Cruz threatened AAA that he will circulate a copy of their sex video to her family and schoolmates if she refused

to go to his house and meet him in order to assure sexual congress. Alarmed by the consequence of his threat, AAA had no

choice but to go to his place as he wanted, in the hope that he would keep his word that he will give her the disk containing

their sex video;

(2)

When Cruz and his friends were having a drinking spree in his house, he threatened AAA that he will ask them to

rape her if she puts her clothes back on. Again, AAA had no choice but to do what he demanded, and thereafter repeatedly

sexually molested her; and,

(3)

Cruz held a lighted cigarette near her chest and warned her that he will burn her skin if she continues to resist his

sexual advances. Helpless, AAA had no choice but to succumb to his demand.

However, the defense denied the contention of the prosecution by saying that Cruz professed his love for AAA and that

AAA consented to the sexual acts, or sweetheart defense. Cruz was arraigned and pleaded not guilty. The RTC

acquitted Cruz in one of the three criminal cases of rape. CA affirmed the RTCs decision.

ISSUE/S:

Did the Court rightfully determined that the testimony of AAA positively identified the accused as the one who sexually

abused her?

HELD:

Yes. The Court held that the clear, consistent and spontaneous testimony of AAA unrelentingly established how Cruz

sexually molested her on November 6, 2007 with the use of force, threat and intimidation. Indeed, [a] rape victim is not

expected to make an errorless recollection of the incident, so humiliating and painful that she might in fact be trying to

obliterate it from her memory. Thus, a few inconsistent remarks in rape cases will not necessarily impair the testimony of

the offended party.

As to the sweetheart defense, it is said that love is not a license for lust. A love affair does not justify rape for a man

does not have the unbridled license to subject his beloved to his carnal desires against her will. Cruzs argument that they

are lovers may be true; however, the sexual incidents between him and AAA on November 6, 2007 have not been proven

to be consensual.

9|P a ge

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

Anita Mangila v. Judge Pangilinan et.al. [G.R. 160739. July 17, 2013.]

FACTS:

On June 16, 2003, seven complaints of syndicated estafa were filed against petitioner and four others. These involved the

modus of the petitioner of recruiting persons for employment as overseas contract workers in Toronto, Canada without

acquiring from the POEA a permit to do so. The next day, Judge Pangilinan conducted a preliminary investigation. After

examining Miguel Aaron Palayon, one of the complainants, Judge Pangilinan issued a warrant for the arrest of Mangila and

her cohorts without bail. On the next day, the entire records of the cases, including the warrant of arrest, were transmitted to

the City Prosecutor of Puerto Princesa City. She was then apprehended on June 18, 2003. Petitioner contends that Judge

Pangilinan did not have the authority to conduct the preliminary investigation; that the preliminary investigation he

conducted was not yet completed when he issued the warrant of arrest.

ISSUE/S:

Did the CA err in ruling that habeas corpus was not the proper remedy to obtain the release of Mangila from detention?

HELD:

No. According to the Supreme Court, there is no question that when the criminal complaints were lodged against Mangila

and her cohorts on June 16, 2003, Judge Pangilinan, as the Presiding Judge of the MTCC, was empowered to conduct

preliminary investigations involving all crimes cognizable by the proper court in their respective territorial jurisdictions.

His authority was expressly provided in Section 2, Rule 112 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, to wit:

Section 2. Officers authorized to conduct preliminary investigations. The following may conduct preliminary

investigations:

(a) Provincial or City Prosecutors and their assistants;

(b) Judges of the Municipal Trial Courts and Municipal Circuit Trial Courts;

(c) National and Regional State Prosecutors; and

(d) Other officers as may be authorized by law.

Their authority to conduct preliminary investigations shall include all crimes cognizable by the proper court in their

respective territorial jurisdictions. (2a)

It further explained by saying that under Section 6(b) of Rule 112of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, the

investigating judge could issue a warrant of arrest during the preliminary investigation even without awaiting its conclusion

should he find after an examination in writing and under oath of the complainant and the witnesses in the form of searching

questions and answers that a probable cause existed, and that there was a necessity of placing the respondent under

immediate custody in order not to frustrate the ends of justice. In the context of this rule, Judge Pangilinan issued the

warrant of arrest against Mangila and her cohorts. Consequently, the CA properly denied Mangilas petition for habeas

corpus because she had been arrested and detained by virtue of the warrant issued for her arrest by Judge Pangilinan, a

judicial officer undeniably possessing the legal authority to do so.

10 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

People v. Victorino Reyes [G.R. 173307. July 17, 2013.]

FACTS:

On December 26, 1996, Reyes allegedly raped minor AAA while she and her sister BBB were on the way to their home

from school. AAA was dragged to the sala of his house and therein, he was able to perform sexual acts which include the

insertion of his penis into her vagina, which created a slight penetration to the latter, and made push and pull movements.

ISSUE/S:

1. Did the CA and RTC erred in ruling that the testitmonies of AAA and BBB were credible and reliable?

2. Did the evidence adduce by the State competently proved that the crime reached the consummated stage?

HELD:

1. No. The Supreme Court held that consequently there was a good reason or cause to have us depart from the age-old rule

of according conclusiveness to the findings of the RTC that the CA affirmed. The Court is not a trier of facts, and has to

depend on the findings of fact of the trial court by virtue of its direct access to the witnesses as they testified in court. Only

when the appellant convincingly demonstrates that such findings of fact were either erroneous, or biased, or unfounded, or

incomplete, or unreliable, or conflicted with the findings of fact of the CA would the Court assume the rare role of a trier of

facts. But that convincing demonstration was not done here by Reyes.

2. Yes. Article 335 of the Revised Penal Code, as amended by Section 11 of Republic Act No. 7659, the law applicable at

the time of the rape of AAA, defined and punished rape thusly:

Article 335. When and how rape is committed. Rape is committed by having carnal knowledge of a woman under any of

the following circumstances:

1. By using force or intimidation;

2. When the woman is deprived of reason or otherwise unconscious; and

3. When the woman is under twelve years of age or is demented.

The crime of rape shall be punished by reclusion perpetua.

The Supreme Court reiterated that the breaking of the hymen of the victim is not among the means of consummating rape.

All that the law required is that the accused had carnal knowledge of a woman under the circumstances described in the

law. By definition, carnal knowledge was "the act of a man having sexual bodily connections with a woman." This

understanding of rape explains why the slightest penetration of the female genitalia consummates the crime.

People vs. Clara [GR No. 195528. July 24, 2013.]

FACTS:

This case involves a buy-bust operation which led to the arrest of the accused JOEL CLARA Y BUHAIN (Joel). Upon the

presentation of the prosecution witnesses, it was evident that there were contradictions between the versions of the

testimonies of the police officers who claimed to have conducted the buy-bust operation. The testimony of PO3 Ramos,

which apparently was given as proof of all the elements that constitute an illegal sale of drug is however, inconsistent on

material points from the recollection of event of PO3 Ramos, SPO2 Nagera and PO1 Jimenez regarding the marking,

handling and turnover of the plastic sachet containing the dangerous drug of shabu.

ISSUE/S:

11 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

Was there failure in the part of the prosecution to establish with certainty the chain of custody of evidence?

HELD:

Yes. The Supreme Court defines Chain of Custody as the duly recorded authorized movement and custody of seized

drugs or controlled chemicals or plant sources of dangerous drugs or laboratory equipment of each stage, from the time of

seizure/confiscation to receipt in the forensic laboratory to safekeeping to presentation in court and finally for destruction.

Such record of movements and custody of seized item shall include the identity and signature of the person who held

temporary custody of the seized item, the date and time when such transfer of custody were made in the course of

safekeeping and use in court as evidence, and the final disposition.

To establish the chain of custody in a buy-bust operation, the prosecution must establish the following links, namely: First,

the seizure and marking, if practicable, of the illegal drug recovered from the accused by apprehending officer; Second, the

turnover of the illegal drug seized by the apprehending officer to the investigating officer; Third, the turnover by the

investigating officer of the illegal drug to the forensic chemist for laboratory examination; and Fourth, the turnover and

submission of the marked illegal drug seized by the forensic chemist to the court.

In Mallillin v. People, it was explained that the chain of custody rule includes testimony about every link in the chain, from

the moment the item was picked up to the time it was offered in evidence, in such a way that every person who touched the

exhibit would describe how and from whom it was received, where it was and what happened to it while in the witness

possession, the condition in which it was received and the condition in which it was delivered to the next link in the chain.

In view of these guiding principles, we rule that the prosecution failed to present a clear picture on how the police officers

seized and marked the illegal drug recovered by the apprehending officer and how the specimen was turned over by the

apprehending officer to the investigating officer. Accused is acquitted.

People v. Roman [G.R. No. 198110. July 31, 2013.]

FACTS:

The accused-appellant, Wilson Roman, was charged with murder.

The incident happened in the morning of June 22, 1995, at the wedding party when the accused-appellant hacked Vicente

Indaya, the victim, with his bolo. The victim was hit on his head, nape, right shoulder, base of the nape and right elbow

before he fell on the ground and then died. There were several witnesses including Elena Romero, Asterio Ebuenga, Martin

Borlagdatan, Elisea Indaya, Ramil Baylon, SPO1 Medardo Delos Santos and Dr. Teodora Pornillos. Each testimonies were

positive, clear and consistent in all material points.

However, there was a different version of the incident according to the accused-appellant. He said that on that day, he went

to the house of his parents-in-law to bring the bamboos. On his way back, he met his close friend who invited him to come

to the wedding party. At the venue, he pacified his brother-in-law and Indaya, the victim who were having a heated

exchange of words and told the victim to leave. After 20 minutes, the victim came back. He got mad because he was

pacified by the accused-appellant and threatened to kill him. But he simply stood up and turned to leave the place. As he

was leaving, he heard a shout that he was about to be hacked. Then, he saw the victim, aiming to hit him with a bolo, but

he was able to get the bolo. He lost control of himself, he hacked the victim instead. His testimony was supported by Delia

Tampoco.

12 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

The Regional Trial Court and Court of Appeals rendered a decision, finding the accused-appellant guilty beyond

reasonable doubt of the crime of murder.

ISSUE/S:

1. Whether or not the accused-appellant may invoke self-defense.

2.

Whether or not the qualifying circumstance of treachery exists.

HELD:

1. No. Self-defense was used as an alibi, an inherently weak defense for it is easy to fabricate. In order for self-defense to

be appreciated, the accused must prove by clear and convincing evidence the following elements: (a) unlawful aggression

on the part of the victim; (b) reasonable necessity of the means employed to prevent or repel it; and (c) lack of sufficient

provocation on the part of the person defending himself.

It is a statutory and doctrinal requirement that, for the justifying circumstance of self-defense, unlawful aggression as a

condition sine qua non must be present. There can be no self-defense, complete or incomplete, unless the victim commits

an unlawful aggression against the person defending himself. There is unlawful aggression when the peril to ones life,

limb or right is either actual or imminent. There must be actual physical force or actual use of a weapon.

Accordingly, the accused must establish the concurrence of three elements of unlawful aggression, namely: (a) there must

be a physical or material attack or assault; (b) the attack or assault must be actual, or, at least, imminent; and (c) the attack

or assault must be unlawful.

Unlawful aggression is of two kinds: (a) actual or material unlawful aggression; and (b) imminent unlawful aggression.

Actual or material unlawful aggression means an attack with physical force or with a weapon, an offensive act that

positively determines the intent of the aggressor to cause the injury. Imminent unlawful aggression means an attack that is

impending or at the point of happening; it must not consist in a mere threatening attitude, nor must it be merely imaginary,

but must be offensive and positively strong. Imminent unlawful aggression must not be a mere threatening attitude of the

victim, such as pressing his right hand to his hip where a revolver was holstered, accompanied by an angry countenance, or

like aiming to throw a pot.

Unfortunately for the accused-appellant, his claim of self-defense shrinks into incredulity. It is worth noting that the

incident transpired in broad daylight, within the clear view of a number of guests. Thus, it is of no wonder that the

testimonies of all the prosecution witnesses are consistent in all material points. They all confirmed that before the crime

was consummated, the victim was only walking in the yard, unarmed. There was not the least provocation done by the

victim that could have triggered the accused-appellant to entertain the thought that there was a need to defend himself. The

victim did not exhibit any act or gesture that could show that he was out to inflict harm or injury. On the contrary, the

witnesses all point to the accused-appellant as the unlawful aggressor who mercilessly hacked the unwary victim until he

collapsed lifeless on the ground.

Moreover, the severity, location and the number of wounds suffered by the victim are indicative of a serious intent to inflict

harm not merely that he wanted to defend himself from an imminent peril to life. Also, in the incident report executed by

the police officers, only one bolo, specifically that which was used in the hacking, was reported to have been recovered

from the crime scene. This belies the accused-appellants claim that the victim was also armed at the time of the incident.

1.

Yes. There was treachery and accused-appellant contention that he should be convicted only of homicide, not

murder was dismissed.

13 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

There is treachery when the offender commits any of the crimes against a person, employing means, methods or forms in

the execution thereof which tend directly and especially to ensure its execution, without risk to himself arising from the

defense which the offended party might make. It takes place when the following elements concur: (1) that at the time of the

attack, the victim was not in a position to defend himself; and (2) that the offender consciously adopted the particular

means of attack employed.

The essence of treachery is the sudden and unexpected attack by the aggressors on unsuspecting victims, depriving the

latter of any real chance to defend themselves, thereby ensuring its commission without risk to the aggressors, and without

the slightest provocation on the part of the victims. But, in the case, the victim was rendered defenseless and unable to

retaliate. He was then unarmed and unsuspecting, was deprived of any real chance to mount a defense, thereby ensuring the

commission of the crime without risk to accused-appellant.

This is also buttressed by the fact that the wounds sustained by the victim were all located at the back. At the time that the

crime was about to be committed, the victim does not have the slightest idea of the impending danger to his person. He was

not facing the accused-appellant and unarmed, hence, lacked the opportunity to avoid the attack, or at least put up a defense

to mitigate the impact. On the one hand, the accused-appellant was armed and commenced his attack while behind the

victim.

Lihaylihay and Vinluan v. People [G.R. No. 191219. July 31, 2013.]

FACTS:

Acting on the special audit reportsubmitted by the Commission on Audit, the Philippine National Police (PNP) conducted

an internal investigation on the purported "ghost" purchases of combat, clothing, and individual equipment (CCIE) worth

P133,000,000.00 which were allegedly purchased from the PNP Service Store System (SSS) and delivered to the PNP

General Services Command (GSC). As a result of the internal investigation, an Information was filed before the

Sandiganbayan, charging 10 PNP officers, including, among others, Vinluan and Lihaylihay, for the crime of violation of

Section 3(e) of RA 3019

Gen. Nazareno in his capacity as Chief, PNP and concurrently Board Chairman of the PNP Service Store System,

surreptitiously channeled PNP funds to the PNP SSS through "Funded RIVs" valued at P8 [M]illion and Director

Domondon released ASA No. 000-200-004-92 (SN-1353) without proper authority from the National Police Commission

(NAPOLCOM) and Department of Budget and Management (DBM), and caused it to appear that there were purchases and

deliveries of combat clothing and individual equipment (CCIE) to the General Service Command (GSC), PNP, by

deliberately and maliciously using funds for personal services and divided the invoices of not more than P500,000.00 each

ISSUE/S:

WON evidence was admissible.

HELD:

Finally, on the matter of the admissibility of the prosecutions evidence, suffice it to state that, except as to the checks,the

parties had already stipulated on the subject documents existence and authenticity and accordingly, waived any objections

thereon. In this respect, petitioners must bear the consequences of their admission and cannot now be heard to complain

against the admissibility of the evidence against them by harking on the best evidence rule. In any event, what is sought to

be established is the mere general appearance of forgery which may be readily observed through the marked alterations and

14 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

superimpositions on the subject documents, even without conducting a comparison with any original document as in the

case of forged signatures where the signature on the document in question must always be compared to the signature on the

original document to ascertain if there was indeed a forgery.

Lee v. Lee [G.R. No. 181658. August 7, 2013.]

FACTS:

Petitioner Paul Lee is the President of Centillion Holding, Inc. (CHI), affiliated with Clothman Knitting Corporation (CKC

Group). Respondent Chin Lee is the elected treasurer of CHI. Paul lee filed a verified petition for the issuance of an

Owners Duplicate Copy of Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT), covering a property owned by CHI. He claims he

originally had in his possession an owners duplicate copy of the TCT but subsequently lost it. In a Complaint-Affidavit,

respondent Chin Lee alleges that as treasurer of CHI, she was tasked with the duty of keeping all vital financial documents

including the said TCT. She claims that Paul Lee knew of this fact and made a willful and deliberate assertion of falsehood

in his verified petition, thereby accusing him of perjury. Paul Lees counsel then moved in open court that respondent Chin

Lee and her counsel should be excluded from participating in the case, since perjury is a public offense, and there is no

private person injured by the crime.

ISSUE/S:

WON there is a private offended party in the crime of perjury, a crime against public interest.

HELD:

YES. Generally, the basis of civil liability arising from crime is the fundamental postulate of our law that "[e]very person

criminally liable . . . is also civilly liable." Underlying this legal principle is the traditional theory that when a person

commits a crime, he offends two entities, namely (1) the society in which he lives in or the political entity, called the State,

whose law he has violated; and (2) the individual member of that society whose person, right, honor, chastity or property

was actually or directly injured or damaged by the same punishable act or omission.

Section 1, Rule 111 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, as amended, provides:

SECTION 1.Institution of criminal and civil actions. (a) When a criminal action is instituted, the civil action for the

recovery of civil liability arising from the offense charged shall be deemed instituted with the criminal action unless the

offended party waives the civil action, reserves the right to institute it separately or institutes the civil action prior to the

criminal action.

|||

For the recovery of civil liability in the criminal action, the appearance of a private prosecutor is allowed under Section 16

of Rule 110:

SEC. 16.Intervention of the offended party in criminal action. Where the civil action for recovery of civil liability is

instituted in the criminal action pursuant to Rule 111, the offended party may intervene by counsel in the prosecution of

the offense.

Section 12, Rule 110 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, as amended, defines an offended party as "the person

against whom or against whose property the offense was committed.

It has also been held that Under Section 16, Rule 110 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, the offended party

may also be a private individual whose person, right, house, liberty or property was actually or directly injured by

the same punishable act or omission of the accused, or that corporate entity which is damaged or injured by the

15 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

delictual acts complained of. Such party must be one who has a legal right; a substantial interest in the subject matter of

the action as will entitle him to recourse under the substantive law, to recourse if the evidence is sufficient or that he has

the legal right to the demand and the accused will be protected by the satisfaction of his civil liabilities. Such interest must

not be a mere expectancy, subordinate or inconsequential. The interest of the party must be personal; and not one based on

a desire to vindicate the constitutional right of some third and unrelated party.

In this case, the statement of petitioner regarding his custody of TCT No. 232238 covering CHI's property and its loss

through inadvertence, if found to be perjured is, without doubt, injurious to respondent's personal credibility and reputation

insofar as her faithful performance of the duties and responsibilities of a Board Member and Treasurer of CHI.

Chavez v. Fria [GR No. 183014. August 7, 2013.]

FACTS:

A case was decided in favor of the plaintiff, wherein the Law Firm of Chavez Miranda ans Aseoche (The Law Firm for

brevity), herein petitioner, acted as counsel. A writ of execution was to be issued to enforce said judgment. Atty. Fria,

respondent in the case at bar, was the Branch Clerk of Court of the Regional Trial Court, and refused to do her ministerial

duty if issuing said writ. She posited that the draft writ was addressed to the Branch Sheriff who was on leave, and she did

not know who was appointed as special Sheriff on his behalf. The prosecutor then issued a memorandum recommending

that she be indicted for the crime of Open Disobedience. The Municipal Trial Court (MTC) dismissed the case for lack of

probable cause. It ruled that not all the elements of the crime were present, especially the second element, that there is a

judgment, decision, or order of a superior authority made within the scope of its jurisdiction and issued with all legal

formalities. The Regional Trial Court (RTC) upheld the MTCs ruling.

ISSUE/S:

WON the RTC erred in upholding the MTCs decision.

HELD:

NO. Under Section 5 (a) of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure, a trial court judge may immediately dismiss a

criminal case if the evidence on record clearly fails to establish probable cause|||

Sec. 5.When warrant of arrest may issue. (a) By the Regional Trial Court. Within ten (10) days from the filing of the

complaint or information, the judge shall personally evaluate the resolution of the prosecutor and its supporting

evidence. He may immediately dismiss the case if the evidence on record clearly fails to establish probable cause. If

he finds probable cause, he shall issue a warrant of arrest, or a commitment order if the accused has already been arrested

pursuant to a warrant issued by the judge who conducted preliminary investigation or when the complaint or information

was filed pursuant to Section 6 of this Rule. In case of doubt on the existence of probable cause, the judge may order the

prosecutor to present additional evidence within five (5) days from notice and the issue must be resolved by the court

within thirty (30) days from the filing of the complaint of information.|||

16 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

It must, however, be observed that the judge's power to immediately dismiss a criminal case would only be warranted when

the lack of probable cause is clear. A clear-cut case of lack of probable cause exists when the records readily show

uncontroverted, and thus, established facts which unmistakably negate the existence of the elements of the crime charged.

it must be stressed that the judge's dismissal of a case must be done only in clear-cut cases when the evidence on

record plainly fails to establish probable cause that is when the records readily show uncontroverted, and thus,

established facts which unmistakably negate the existence of the elements of the crime charged. On the contrary, if

the evidence on record shows that, more likely than not, the crime charged has been committed and that respondent is

probably guilty of the same, the judge should not dismiss the case and thereon, order the parties to proceed to trial. In

doubtful cases, however, the appropriate course of action would be to order the presentation of additional evidence.

In other words, once the information is filed with the court and the judge proceeds with his primordial task of evaluating

the evidence on record, he may either: (a) issue a warrant of arrest, if he finds probable cause; (b) immediately dismiss the

case, if the evidence on record clearly fails to establish probable cause; and (c) order the prosecutor to submit

additional evidence, in case he doubts the existence of probable cause.

MTCs dismissal should be sustained.

The second element of the crime of Open Disobedience is that there is a judgment, decision, or order of a superior

authority made within the scope of its jurisdiction and issued with all legal formalities. In this case, it is undisputed that all

the proceedings in Civil Case No. 03-110 have been regarded as null and void due to Branch 203's lack of jurisdiction over

the said case. The third element of the crime, i.e., that the offender, without any legal justification, openly refuses to

execute the said judgment, decision, or order, which he is duty bound to obey, cannot equally exist. Indubitably, without

any jurisdiction, there would be no legal order for Atty. Fria to implement or, conversely, disobey. Besides, as the MTC

correctly observed, there lies ample legal justifications that prevented Atty. Fria from immediately issuing a writ of

execution.

Neri v. Sandiganbayan [GR No. 202243. August 7, 2013.]

FACTS:

Petitioner Romulo L. Neri (Neri) served as Director General of the National Economic and Development Authority

(NEDA) during the administration of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. In connection with the botched

Philippine-ZTE National Broadband Network (NBN) Project, the Ombudsman filed two criminal informations, the first

against Abalos, and the second against Neri. The Office of the Special Prosecutor then moved for the two cases

consolidation, to promote a more expeditious and less expensive resolution of of the controversy of cases involving the

same business transaction.

ISSUE/S:

WON Consolidation of the two cases is proper.

17 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

HELD:

NO. Consolidation is a procedural device granted to the court as an aid in deciding how cases in its docket are to be tried so

that the business of the court may be dispatched expeditiously while providing justice to the parties. Toward this end,

consolidation and a single trial of several cases in the court's docket or consolidation of issues within those cases are

permitted by the rules.

The term "consolidation" is used in three (3) different senses or concepts, thus: a

(1)Where all except one of several actions are stayed until one is tried, in which case the judgment [in one] trial is

conclusive as to the others. This is not actually consolidation but is referred to as such. (quasi consolidation)

(2)Where several actions are combined into one, lose their separate identity, and become a single action in which a single

judgment is rendered. This is illustrated by a situation where several actions are pending between the same parties stating

claims which might have been set out originally in one complaint. (actual consolidation)

(3)Where several actions are ordered to be tried together but each retains its separate character and requires the entry of a

separate judgment. This type of consolidation does not merge the suits into a single action, or cause the parties to one

action to be parties to the other. (consolidation for trial)

To be sure, consolidation, as taken in the above senses, is allowed, as Rule 31 of the Rules of Court is entitled

"Consolidation or Severance." And Sec. 1 of Rule 31 provides:

Section 1.Consolidation. When actions involving a common question of law or fact are pending before the court, it may

order a joint hearing or trial of any or all the matters in issue in the actions; it may order all actions consolidated; and it

may make such orders concerning proceedings therein as may tend to avoid unnecessary costs or delay.

The counterpart, but narrowed, rule for criminal cases is found in Sec. 22, Rule 119 of the Rules of Court stating:

Sec. 22.Consolidation of trials of related offenses. Charges for offenses founded on the same facts or forming part of a

series of offenses of similar character may be tried jointly at the discretion of the court. (Emphasis added.)

As complemented by Rule XII, Sec. 2 of the Sandiganbayan Revised Internal Rules which states:

Section 2.Consolidation of Cases. Cases arising from the same incident or series of incidents, or involving common

questions of fact and law, may be consolidated in the Division to which the case bearing the lowest docket number is

raffled.

The prosecution anchored its motion for consolidation partly on the aforequoted Sec. 22 of Rule 119 which indubitably

speaks of a joint trial.|||

Joint trial is permissible "where the [actions] arise from the same act, event or transaction, involve the same or like issues,

and depend largely or substantially on the same evidence, provided that the court has jurisdiction over the cases to be

consolidated and that a joint trial will not give one party an undue advantage or prejudice the substantial rights of any of

the parties." More elaborately, joint trial is proper where the offenses charged are similar, related, or connected, or are of

the same or similar character or class, or involve or arose out of the same or related or connected acts, occurrences,

transactions, series of events, or chain of circumstances, or are based on acts or transactions constituting parts of a common

scheme or plan, or are of the same pattern and committed in the same manner, or where there is a common element of

substantial importance in their commission, or where the same, or much the same, evidence will be competent and

18 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

admissible or required in their prosecution, and if not joined for trial the repetition or reproduction of substantially the same

testimony will be required on each trial.

|||

Criminal prosecutions primarily revolve around proving beyond reasonable doubt the existence of the elements of the

crime charged. As such, they mainly involve questions of fact. There is a question of fact when the doubt or difference

arises from the truth or the falsity of the allegations of facts. Put a bit differently, it exists when the doubt or difference

arises as to the truth or falsehood of facts or when the inquiry invites calibration of the whole gamut of evidence

considering mainly the credibility of the witnesses, the existence and relevancy of specific surrounding circumstances as

well as their relation to each other and to the whole, and the probability of the situation.|

A consolidation of the Neri case to that of Abalos would expose petitioner Neri to testimonies which have no relation

whatsoever in the case against him and the lengthening of the legal dispute thereby delaying the resolution of his case.

Consolidation here would force petitioner to await the conclusion of testimonies against Abalos, however irrelevant or

immaterial as to him (Neri) before the case against the latter may be resolved a needless, hence, oppressive delay in the

resolution of the criminal case against him.

Hasegawa v. Giron [G.R. No. 184536, August 14, 2013.]

FACTS:

Respondent Giron filed a Complaint Affidavit for Kidnapping and Serious Illegal Detention against petitioner Masayuki

Hasegawa and several John Does. Leila Giron and Leonarda Marcos were allegedly kidnapped by orders of Masayuki

Hasegawa. The kidnapping were done to threaten them as Giron and Marcos filed a case against Hasegawa for illegal

salary deductions, non-payment of 13th month pay, and non-remittance of SSS contributions. Prior to the complaint of

kidnapping, respondent had also filed separate complaints for grave threats, grave coercion, slander and unjust vexation

against petitioner. Hasegawa denied the accusations and asserted that Giron and Marcos only want to extort money from

him.

The State prosecutor dismissed the complaint for lack of probable cause. Respondent then filed a Petition for Review to the

Department of Justice praying for reversal of the prosecutors resolution. The Department of Justice found no basis to

overturn the findings of the Investigating Prosecutor and affirmed its decision that there was a lack of probable cause. She

then filed a petition for certiorari before the Court of Appeals. The Court of Appeals granted the petition, reversed and set

aside the Resolutions of the DOJ and ordered the filing of an Information for Kidnapping and Serious Illegal Detention

against petitioner. Hence, this petition.

Petitioner asserts that the Secretary of Justice clearly and sufficiently explained the reasons why no probable cause exists in

this case. Petitioner argues that a review of facts and evidence made by the appellate court is not the province of the

extraordinary remedy of certiorari. Finally, petitioner contends that the appellate court should have dismissed outright

respondent's petition for certiorari for failure to exhaust administrative remedies and for being the wrong mode of appeal.

ISSUE/S:

1.

Whether or not the CA has jurisdiction?

2.

Was there probable cause?

3.

What kind of evidence is needed for preliminary investigation?

HELD:

19 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

1. YES. The decision whether or not to dismiss the criminal complaint against the accused depends on the sound discretion

of the prosecutor. Courts will not interfere with the conduct of preliminary investigations, or reinvestigations, or in the

determination of what constitutes sufficient probable cause for the filing of the corresponding information against an

offender. Courts are not empowered to substitute their own judgment for that of the executive branch. Differently stated, as

the matter of whether to prosecute or not is purely discretionary on his part, courts cannot compel a public prosecutor to

file the corresponding information, upon a complaint, where he finds the evidence before him insufficient to warrant the

filing of an action in court. In sum, the prosecutor's findings on the existence of probable cause are not subject to review by

the courts, unless these are patently shown to have been made with grave abuse of discretion. We find such reason for

judicial review here present. We sustain the appellate court's reversal of the ruling of the Secretary of the DOJ

2. YES. Probable cause has been defined as the existence of such facts and circumstances as would excite the belief in a

reasonable mind, acting on the facts within the knowledge of the prosecutor, that the person charged was guilty of the

crime for which he was prosecuted. It is a reasonable ground of presumption that a matter is, or may be, well-founded on

such a state of facts in the mind of the prosecutor as would lead a person of ordinary caution and prudence to believe, or

entertain an honest or strong suspicion, that a thing is so. The term does not mean "actual or positive cause" nor does it

import absolute certainty. It is merely based on opinion and reasonable belief. Thus, a finding of probable cause does not

require an inquiry into whether there is sufficient evidence to procure a conviction. It is enough that it is believed that the

act or omission complained of constitutes the offense charged. A finding of probable cause needs only to rest on evidence

showing that, more likely than not, a crime has been committed by the suspects. It need not be based on clear and

convincing evidence of guilt, not on evidence establishing guilt beyond reasonable doubt, and definitely not on evidence

establishing absolute certainty of guilt. In determining probable cause, the average man weighs facts and circumstances

without resorting to the calibrations of the rules of evidence of which he has no technical knowledge. He relies on common

sense. What is determined is whether there is sufficient ground to engender a well-founded belief that a crime has been

committed, and that the accused is probably guilty thereof and should be held for trial. It does not require an inquiry as to

whether there is sufficient evidence to secure a conviction. In order to arrive at probable cause, the elements of the crime

charged should be present. All elements of the crime of kidnapping and serious illegal detention under Article 267 of

the Revised Penal Code were sufficiently averred in the complaint-affidavit in this case and were sufficient to

engender a well-founded belief that a crime may have been committed and petitioner may have committed it.

3. Only evidence to support a finding of probable cause, not a conviction, is needed for preliminary

investigation. All elements of the crime of kidnapping and serious illegal detention under Article 267 of the Revised Penal

Code were sufficiently averred in the complaint-affidavit in this case and were sufficient to engender a well-founded belief

that a crime may have been committed and petitioner may have committed it. Respondent, an office worker, claimed that

she and her friend were taken at gunpoint by two men and forcibly boarded into a vehicle. They were detained for more

than 24 hours. Whether or not the accusations would result in a conviction is another matter. It is enough, for purposes of

the preliminary investigation that the acts complained of constitute the crime of kidnapping and serious illegal detention.

The Investigating Prosecutor, however, ruled that the kidnapping and serious illegal detention charge is a mere fabrication.

The Supreme Court said that the Investigating Prosecutor has set the parameters of probable cause too high. Her findings

dealt mostly with what respondent had done or failed to do after the alleged crime was committed. She delved into

evidentiary matters that could only be passed upon in a full-blown trial where testimonies and documents could be fairly

evaluated in according with the rules of evidence. The issues upon which the charges are built pertain to factual matters

that cannot be threshed out conclusively during the preliminary stage of the case. Precisely, there is a trial for the

presentation of prosecutions evidence in support of the charge. The validity and merits of a partys defense or accusation,

as well as admissibility of testimonies and evidence, are better ventilated during trial proper than at the preliminary

investigation level.

20 | P a g e

Criminal Procedure Cases

(July-December 2013)

People v. Pepino-Consulta [G.R. No. 191071. Aug. 28, 2013.]

FACTS:

Prosecution evidence showed that on February 7, 2005 at 5:10 in the afternoon or thereabouts, a buy-bust operation was

conducted in front of Akim Restaurant located at Cleofers building City of San Fernando against a certain Manang who