Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessment 1

Uploaded by

api-2973892210 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views6 pagesSocial justice in mathematics, as equity for all students. Problem solving, technology and collaboration are all resources that are used widely in mathematics. A student who is told they are 'good' at mathematics is going to feel more confident.

Original Description:

Original Title

assessment 1

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSocial justice in mathematics, as equity for all students. Problem solving, technology and collaboration are all resources that are used widely in mathematics. A student who is told they are 'good' at mathematics is going to feel more confident.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views6 pagesAssessment 1

Uploaded by

api-297389221Social justice in mathematics, as equity for all students. Problem solving, technology and collaboration are all resources that are used widely in mathematics. A student who is told they are 'good' at mathematics is going to feel more confident.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Teaching For Diversity

Overview Argument For Socially Just Teaching

Of Mathematics

Mathematics in the classroom, like any subject and lesson should be

taught in a way that is socially just. Social justice in mathematics, as

equity for all students, thus allowing them to be engaged and feel

as though they are becoming mathematicians who belong to school

and community mathematics contexts. If teachers are able to create

a socially just mathematics classroom, their students will value and

achieve in mathematics. Jorgensen & Niesche (2008, p. 21) state

processes of exclusion operate to disadvantage students along

social class, race and gender lines. This statement serves to

provide further support to the idea that children need to face equity

in the classroom, despite the differences between them, in order to

achieve. In the mathematics classroom, there are two key factors

that influence the learning environment. Expectations set by

teachers and students, for example, a student who views

themselves as a failure in mathematics is not going to work to

achieve any higher than this. Ability of students sets the

framework for students believing they can or cant do well in

mathematics, thus a student who is told they are good at

mathematics is going to feel much more confident than one who is

not told so, or is even told they are bad. (Jorgensen & Niesche,

2008) For teachers, this means that the more equal and more fairly

students are treated, the more likely they are to achieve their

potential in the mathematics classroom. There are many ways

teachers are able to differentiate the curriculum in order to create a

socially just classroom. Problem solving, technology and

collaboration are all resources that are used widely in mathematics,

and can provide educators opportunities to create rich, socially just

lessons. When teachers consider factors that may influence their

students learning and development, such as gender and cultural

background, they will be more able to take into account the

diversity of their classroom. This will allow teachers to understand

their students and create the best possible lessons for them.

Problem Solving As A Tool For Differentiating

The Curriculum

Problem solving is defined by Bobis, Mulligan & Lowrie (2013) as

when children choose, interpret, formulate, model and investigate

problems, then communicate and verify their solutions. It is

essential to teaching mathematics, and is a strategy that is learned

and taught in all classrooms. Despite its prominence and

importance, sometimes incorporating differentiation into problem

EMM310 Lucy Walker

Isabel Horton 11477162A

Assessment Item 1

solving lessons can cause trouble for some teachers. Williams

presents a range of problem solving task in which challenges exist

for all ability levels, [and] different aspects of the investigation

challenge different students. (1996, p. 9) Teachers should consider

approaches to planning that enable all learners to engage in

mathematics lessons, experiencing the same tasks and joining in

the mathematics conversation of the classroom. (Siemon, Beswick,

Brady, Clark, Faragher, & Warren, 2011)

Technology As A Tool For Engagement

Technology has become an unmoving, while ever-changing, fixture

in classrooms. Teachers and students have come to rely on

technology for many areas of learning, in particular the engagement

of students. (Ozel, Yetkiner, & Capraro, 2008) Despite the excellent

resource technology provides, teachers must be aware that the

same deep thought process and planning must go into the use of

technology in the classroom, the same way it would for any other

lesson. Teachers also need to gain the technological knowledge

needed to effectively implement ICT into their lessons, along with

the content and pedagogical knowledge that would have used

otherwise. Technology can be used in the classroom in many ways,

which can be categorised under four headings, technology as a

business resource, as a subject, as content delivery and as lesson

support. Teachers should not only plan the technological resources

they will use in their lesson, but plan exactly how they will be used.

(Bitter & Legacy, 2008) Technology is used in many classrooms in a

huge variety of ways. Interactive whiteboards are one resource that

is common across many schools in Australia, and is an excellent way

for teachers to engage students in a whole group lesson, while

implementing technology in a subtle but useful way. Most students

also have access to computers and iPads, which allow them to work

through online activities, and mathematics based games and

applications. These resources can be used by teachers to both

differentiate lessons quickly and easily, and engage students in new

technologies that they are experienced in using and enjoy.

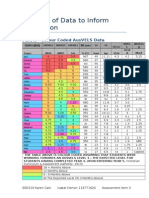

Figure 1: Technology

Technology as lesson support

The use of the web page Rainforest Maths is an excellent

resource to use in the classroom, for a wide range of diverse

learners. The resource has many different tasks, which can be

chosen by level of difficulty or area of learning. The web page is

accessible to students through an iPad or computer, and can be

accessed by the teacher on the IWB in order to model the task, or

as a resource for a whole group activity.

Information sourced during professional experience at Osbornes

Flat Primary School.

EMM310 Lucy Walker

Isabel Horton 11477162A

Assessment Item 1

Figure 1 discusses the way technology can be implemented simply

in the classroom. Students and teachers are both able to access

resources such as these, and will thus be able to plan and use them

in lessons. The use of resources similar to that outlined in Figure 1 is

common to many classrooms, and has enabled many teachers to

engage their students with the use of technology.

Collaboration As A Tool For Effective Problem

Solving

Having students work cooperatively, competitively or

individualistically has important implications for the success of math

instruction. (Johnson & Johnson, 1990, p. 103) Yackel, Cobb and

Wood (1991) discuss an experiment undertaken in a second grade

classroom, in which they added a high level of collaborative

activities to the mathematics teaching for an entire year. Each onehour lesson consisted of around 25 minutes of small group problem

solving, 25 minutes of whole class discussion and 10 minutes of

introductory teaching. Some examples of the benefits of

collaboration found during the experiment include students being

able to [make] sense of situations in terms of their current

concepts and procedures, [they were noted to be] accounting for a

surprise outcome, verbalising their mathematical thinking,

explaining or justifying a solution, [finding] alternative solution

methods and formulating an explanation to justify another childs

solution attempt. (Yackel, Cobb, & Wood, 1991, p. 395) Learning is

fundamentally a social process (Gray, 1990) and though the use

of collaboration as a strategy for all learning areas is important, its

use in problem solving during mathematics is certain.

Figure 2: Collaboration

Sourced from: Teaching Numeracy (Pearse & Walton, 2009)

Figure 2 demonstrates the simplicity of using collaboration in the

mathematics classroom. While this lesson begins with students

working independently, they are able to share their work with their

EMM310 Lucy Walker

Isabel Horton 11477162A

Assessment Item 1

partner, thus developing a wider knowledge base, than had they

worked solely alone.

Consideration Of Gender In Collaborative,

Technology-Based Learning

As teachers, understanding the differences in teaching boys and

girls in vital to successful classroom management and learning.

Boys and girls are different. One is not better than the other; they

are just different. As a result, we can expect that a difference exists

in how boys and girls learning the way they learn. (Geist & King,

2008) These differences affect both genders in learning, and in

particular collaborative, technology based learning. In mathematics,

often girls have less confidence in their [mathematical] abilities

than boys despite no gender differences in measured

[mathematical] achievement. (Watt, 2007, pp. 37 - 38)

Understanding this, along with the teaching strategies outlined in

Figure 4 should effectively assist teachers in developing a stronger

learning plan for both boys and girls in the classroom.

Figure 3: Gender

Strategies for assisting boys and girls to learn mathematics

Girls:

Include group work, opportunities for discussion in both small groups

and whole-class setting and contexts of interest to girls.

Provide assessment opportunities that allow for a variety of

responses.

Ensure contexts are understood.

Use contextual tasks; include tasks that show the value of

mathematics to the solution of social problems and verbal and

linguistic approaches.

Engage learners with problems set in real contexts.

Boys:

Structure activities and assignments, with long deadlines.

Assist learners to break tasks into achievable steps.

Check homework regularly.

Employ clearly defined objectives and instructions.

Ensure all students in the class are clear about what they are

required to do.

Put the tasks on the whiteboard to ensure they are retrievable.

Set short-term challenging tasks.

Include tasks with a focus of mathematical thinking for all learners in

the class.

Adapted from: Teaching Mathematics: Foundation to Middle Years

(Siemon, Beswick, Brady, Clark, Faragher, & Warren, 2011, p. 157)

While using collaboration in the classroom, especially in technologybased learning, noting the differences in gender must not be

underestimated. Figure 3 highlights the importance of providing

EMM310 Lucy Walker

Isabel Horton 11477162A

Assessment Item 1

female learners with opportunities for group work, while male

learners do not benefit as greatly from this strategy. Thus while

female learners will gain valuable skills from working collaboratively,

with ICT, perhaps using short individualised tasks on computers or

iPads would be more suitable for males.

Consideration Of Culture, Multilingual

Students In Mathematics Teaching

In every classroom, a teacher will be responsible for a range of

students, with a range of backgrounds and abilities. Students may

have an Indigenous or non-English speaking background, a mental

or physical disability or be other exceptional students, meaning

students whom are not the norm, for example gifted and talented or

those with learning difficulties. Considering the impact of a students

culture on their learning is necessary in understanding the needs of

that student. Mathematics is sometimes assumed to be culturefree, and students lack of understanding is thought to be caused

by a lack of ability. Indigenous students have prior mathematical

experiences that they bring to the classroom, though sometimes

their teacher may overlook these, as they do not meet the teachers

expectations. Valuing students prior learning and experiences, or

funds of knowledge will allow all students to find success in the

mathematics classroom. If current mathematics teaching remains

unchanged, pedagogy will tend to reproduce social inequalities of

achievement and subordinate individual development to social

domination for Aboriginal children. (Teese, 2000)

Conclusion On Socially Just Teaching

Practices In Mathematics

The importance of catering for all students needs, learning styles

and abilities within the classroom is paramount to providing a

socially just learning environment. When a teacher is able to take

the diversity of their classroom into consideration when planning

lessons, and using collaboration, technology and problem solving in

teaching mathematics, they are able to best achieve a fair and

equal ground for all students to reach their potential.

References

Bitter, G. G., & Legacy, J. M. (2008). Planning and developing

technology-rich instruction. In Using technology in the classroom

(pp. 162 - 193). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Bobis, J., Mulligan, J., & Lowrie, T. (2013). Mathematics for Children:

Challenging children to think mathematically. Frenchs Forest:

Pearson Australia.

EMM310 Lucy Walker

Isabel Horton 11477162A

Assessment Item 1

Geist, E. A., & King, M. (2008). Different, not better: Gender

differences in mathematics learning and achievement. Journal of

Instructional Psychology , 35 (1), 43 - 52.

Gray, B. (1990). Natural language learning in Aboriginal classrooms:

Reflections on teaching and learning style for empowerment in

English. In C. Walton, & W. Eggington, Language: Maintenance,

power and education in Australian Aboriginal Contexts (pp. 105 139). Darwin: Northern Territory University Press.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1990). Using cooperative learning in

math. In N. Davidson, Cooperative learning in Mathematics: A

handbook for teachers (pp. 103 - 125). Menlo Park, Calif: AddisonWesley.

Jorgensen, R., & Niesche, R. (2008). Equity, mathematics and

classroom practice: Developing rich mathematical experiences for

disadvantaged students. Australian Primary Mathematics Classroom

, 14 (4), 21 - 27.

Ozel, s., Yetkiner, Z. E., & Capraro, R. M. (2008). Technology in K - 12

Mathematics Classrooms. School Science and Mathematics , 108 (2),

80 - 85.

Pearse, M. M., & Walton, K. M. (2009). Appendix A: Sample Lesson 1:

Introduction To Division (Grades 2 - 3). In Teaching Numeracy: 9

Critical Habits to Ignite. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Corwin.

Siemon, D., Beswick, K., Brady, K., Clark, J., Faragher, R., & Warren,

E. (2011). Teaching Mathematics: Foundation to Middle Years. South

Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Teese, R. (2000). Academic success and social power. Carlton, VIC:

Melbourne University Press.

Watt, H. G. (2007). A trickle from the pipeline: Why girls underparticipate in maths. Professional Educator , 6 (3), 36 - 41.

Williams, G. (1996). Unusual connections: Maths through

investigation. Brighton, VIC: Gaye Williams.

Yackel, E., Cobb, P., & Wood, T. (1991). Small-group interactions as a

source of learning opportunities in mathematics. Journal for

Research in Mathematics Education , 22 (5), 390 - 408.

EMM310 Lucy Walker

Isabel Horton 11477162A

Assessment Item 1

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Gifted Students in LiteratureDocument8 pagesGifted Students in Literatureapi-337650425No ratings yet

- Assessment 1Document13 pagesAssessment 1api-297389221100% (1)

- Assessment 1 Part A Final DraftDocument9 pagesAssessment 1 Part A Final Draftapi-2973892210% (1)

- NSW Det Code of ConductDocument36 pagesNSW Det Code of Conductapi-297389221No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - Culture Treasure BoxDocument5 pagesLesson Plan - Culture Treasure Boxapi-242601706No ratings yet

- SMEADocument96 pagesSMEAChristopher AgsunodNo ratings yet

- Fs 6Document29 pagesFs 6api-31001264880% (5)

- (Chapter 1-3) Effects of Mobile Technology Usage On Academic Performance of Grade 11 Stem Students at Ama Computer College Lipa School Year 2018-2019 PDFDocument24 pages(Chapter 1-3) Effects of Mobile Technology Usage On Academic Performance of Grade 11 Stem Students at Ama Computer College Lipa School Year 2018-2019 PDFNica Jeatriz Aguisanda86% (21)

- New Grammar Time 2 SBDocument107 pagesNew Grammar Time 2 SBКристина МаксимоваNo ratings yet

- Professional Experience Goals 2014Document2 pagesProfessional Experience Goals 2014api-297389221No ratings yet

- Final Report - Isabel Horton - SignedDocument10 pagesFinal Report - Isabel Horton - Signedapi-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document7 pagesAssessment 2api-297389221No ratings yet

- Critiquing Assessment Items: Activity 1 - Stage 1 - Money MattersDocument9 pagesCritiquing Assessment Items: Activity 1 - Stage 1 - Money Mattersapi-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document26 pagesAssessment 2api-297389221100% (1)

- 2014 Child Protection - 2nd LevelDocument35 pages2014 Child Protection - 2nd Levelapi-297389221No ratings yet

- Child Protection E-Learning Certificate 13 9 14 1Document1 pageChild Protection E-Learning Certificate 13 9 14 1api-297389221No ratings yet

- Eee314 Ass 3Document4 pagesEee314 Ass 3api-297389221No ratings yet

- Lessons Plans - Geography Stage 6Document3 pagesLessons Plans - Geography Stage 6api-297389221No ratings yet

- Introduction To Ancient IndiaDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Ancient Indiaapi-297389221No ratings yet

- EMR302 PDHPE Curriculum Assignment Criteria and Mark Sheet Subject Coordinator: Kelly Parry Assignment 1Document30 pagesEMR302 PDHPE Curriculum Assignment Criteria and Mark Sheet Subject Coordinator: Kelly Parry Assignment 1api-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document39 pagesAssessment 2api-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document14 pagesAssessment 2api-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 1Document9 pagesAssessment 1api-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document39 pagesAssessment 2api-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document26 pagesAssessment 2api-297389221100% (1)

- Nasa Astronaut Data Collection PackDocument4 pagesNasa Astronaut Data Collection Packapi-297389221No ratings yet

- Geography - Population Distribution - 6 2 14Document4 pagesGeography - Population Distribution - 6 2 14api-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document14 pagesAssessment 2api-297389221No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document26 pagesAssessment 2api-297389221100% (1)

- Article 4Document14 pagesArticle 4api-259447040No ratings yet

- SLA Written AssignmentDocument5 pagesSLA Written AssignmentyuoryNo ratings yet

- Makalsh CMDDocument22 pagesMakalsh CMDMaudy Rahmi HasniawatiNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report Brigada Eskwela 2021Document20 pagesNarrative Report Brigada Eskwela 2021Benmar L. OrterasNo ratings yet

- Improving Students' Writing Skills Through The Application of Synectic Model of Teaching Using Audiovisual MediaDocument15 pagesImproving Students' Writing Skills Through The Application of Synectic Model of Teaching Using Audiovisual MediaEli MelozNo ratings yet

- The Technological Benefits of Using A Laptop in ClassroomsDocument5 pagesThe Technological Benefits of Using A Laptop in ClassroomsMaricel ViloriaNo ratings yet

- Classroom Observation and ResearchDocument12 pagesClassroom Observation and ResearchVerito VeraNo ratings yet

- TKT ActivitiesDocument17 pagesTKT ActivitiesGuadalupe GódlenNo ratings yet

- Standard Classroom UpgradeDocument14 pagesStandard Classroom UpgradeRomeo PascuaNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Analysis FVDocument5 pagesRhetorical Analysis FVapi-299719075No ratings yet

- E Portfolio For Pre Service Teachers 1Document125 pagesE Portfolio For Pre Service Teachers 1April Joy GuanzonNo ratings yet

- Action Plan Template With First Meeting AgendaDocument3 pagesAction Plan Template With First Meeting AgendatinalNo ratings yet

- Elementary Teaching Matrix GamesDocument2 pagesElementary Teaching Matrix GamesckratchaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Tablets on Grade 12 Academic PerformanceDocument47 pagesEffects of Tablets on Grade 12 Academic PerformanceMhayen Ann AbelleraNo ratings yet

- fs1 Episode 6Document6 pagesfs1 Episode 6Jamille Nympha C. BalasiNo ratings yet

- Part A. Common Misconceptions About Force and Motion:: Carly Zenk 3 GradeDocument3 pagesPart A. Common Misconceptions About Force and Motion:: Carly Zenk 3 GradePanji SaksonoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines for Multigrade Class OrganizationDocument3 pagesGuidelines for Multigrade Class OrganizationDara Rose FilosofoNo ratings yet

- Teaching Social Studies With Video GamesDocument6 pagesTeaching Social Studies With Video GamesJavier SevillaNo ratings yet

- DepEd Lanao del Norte Job Order ContractDocument2 pagesDepEd Lanao del Norte Job Order Contractبن قاسمNo ratings yet

- Complete PDFDocument495 pagesComplete PDFMárcio MoscosoNo ratings yet

- Group 6 Session Guide Environmental Factors Affecting MotivationDocument4 pagesGroup 6 Session Guide Environmental Factors Affecting Motivationdennis padawan100% (1)

- Lesson Plan 4 - Social Health FinalDocument13 pagesLesson Plan 4 - Social Health Finalapi-301978677No ratings yet

- Group Project Edsp 355bDocument10 pagesGroup Project Edsp 355bapi-535394816No ratings yet

- Allison Baricko ResumeDocument1 pageAllison Baricko Resumeapi-255451636No ratings yet