Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cyberbullying

Uploaded by

api-306195061Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cyberbullying

Uploaded by

api-306195061Copyright:

Available Formats

July 2007

Cyberbullying

Policy Considerations for Boards

Schools have long had to deal with bullying among students,

including hitting, teasing, name-calling, intimidation,

harassment and social exclusion. But in recent years,

technology has given teenagers, and even younger students, a

new and more anonymous venue for bullying their peers.

Students are frequent users of the Internet and other

technologies sending e-mail, creating Web sites, posting

personal news in blogs (online interactive journals),

sending text messages and images via cell phones,

contacting each other through instant messages (IMs),

posting on social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, MySpace,

Xanga), and posting to discussion boards. Now, students

are using these technologies to bully their peers and

sometimes to harass school staff.

The challenge for schools is not only in identifying and

stopping such conduct so that students and staff feel safe at

school, but determining the limits of their authority when

the so-called cyberbullying is initiated outside of school and

during non-school hours.

What is cyberbullying?

Cyberbullying, sometimes referred to as Internet bullying

or electronic bullying, has been defined as the willful and

repeated harm inflicted through the medium of electronic

text.1 It may involve:

sending mean, vulgar or threatening messages or

images;

posting sensitive, private information about another

person;

intentionally excluding someone from an online

group.2

Like other forms of bullying, cyberbullying is an effort to

demonstrate power and control over someone perceived as

weaker. It sometimes involves relationships, sometimes is

based on hate or bias (e.g., based on race, religion, sexual

orientation or physical appearance), and sometimes is

perceived as a game by those who are the perpetrators.

Cyberbullying may be a carryover of bullying that

is occurring at school. Sometimes students who are

victimized at school retaliate online and become

cyberbullies themselves.

Why do people do things online that they would never

do in real life? Researchers have theorized that when

people use the Internet, they perceive they are invisible

and anonymous. This is not true because most online

activities can be traced. However, if someone perceives he

or she is invisible, this removes concerns about detection,

disapproval or punishment. Also, the lack of face-to-face

contact leads to less empathy by the perpetrator toward the

victim and results in the misperception that no real harm

has resulted.3

Extent of the problem

The growing use of the Internet and other technologies

among todays youth suggests that cyberbullying is likely

to become an increasing problem. A national survey

conducted in 2005 showed that 87% of teenagers use the

Internet; 68% of all teenagers said they use the Internet

at school. This represents about a 45% increase over four

years.4

pretending to be someone else in order to make that

person look bad; and

1

Patchin, J.W., & Hinduja, S. (2006) Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyber bullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice,

4(2), 148-169.

Willard, N. (2005), cited in U.S. Department of Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Fact Sheet, http://stopbullyingnow.hrsa.gov

Willard, N. (2007, April) Educators Guide to Cyberbullying and Cyberthreats. Center for Safe and Responsible Use of the Internet.

Pew Internet Project (2005, August 2) The Internet at School. www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/163/report_display.asp

Recent research related to the incidence of cyberbullying

has found:

did not know who had cyberbullied them. Of those

who did know, 62% said they had been cyberbullied

by another student at school and 46% had been

cyberbullied by a friend.12

18% of students in grades 6-8 said they had been

cyberbullied at least once in the last couple of months,

and 6% said it had happened to them two or more times.5

How does cyberbullying impact

victims and bullies?

11% of students in grades 6-8 said they had

cyberbullied someone in the last couple of months.

Of these, 60% had cyberbullied another student at

school and 56% had cyberbullied a friend.6

Although there has been little research specifically on the

effects of cyberbullying, traditional bullying has been shown

to cause psychological and emotional harm to youth and to

affect school attendance and academic performance. Low

self-esteem, depression, anger and, in extreme cases, school

violence or suicide have been linked to bullying.

One-third of teens ages 12-17 and one-sixth of children

ages 6-11 reported that someone said threatening or

embarrassing things about them through e-mail, instant

messages, Web sites, chat rooms or text messages.7

A 2001 fact sheet on juvenile bullying by the Office of

Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention reports that

victims of bullying fear going to school and experience

feelings of loneliness, humiliation and insecurity. They

also tend to struggle with relationships and have difficulty

making emotional and social adjustments.13

Twice as many children and youth indicated that

they had been victims and perpetrators of online

harassment in 2005 compared with 1999-2000.8

Girls are about twice as likely as boys to be victims

and perpetrators of cyberbullying.9

In another study on the effects of traditional bullying,

38% of the victims said they felt vengeful, 37% were

angry and 24% felt helpless. In this same study, 8% of the

students surveyed said traditional bullying has affected

them to the point where they had attempted suicide, run

away, refused to go to school or been chronically ill.14

38.3% of girls ages 8-17, the majority of whom were

in high school, said they had been bullied online.

Higher numbers were reported for specific behaviors

such as being ignored (45.8%) and being disrespected

(42.9%). But some girls did report more serious

behaviors such as being threatened (11.2%).10

It is reasonable to expect that cyberbullying would have

similar effects. Nancy Willard, executive director of the

Center for Safe and Responsible Use of the Internet, believes

the harm caused by cyberbullying could possibly be even

greater than the harm caused by traditional bullying

because online communications can be distributed

worldwide and are often irretrievable; cyberbullies seem

anonymous and can solicit the involvement of unknown

friends; and teens may be reluctant to tell adults what is

happening because they fear their online activities or cell

phone use will be restricted.15

Of the girls ages 8-17 who reported being a victim

of online bullying, only 20.5% said they never knew

who was bullying them. Thus, most appear to know

the bully and report that the bully was a friend from

school (31.3%), someone else from school (36.4%) or

someone from a chat room (28.2%).11

A different result was found among those students in

grades 6-8 who had been cyberbullied at least twice

in the last couple of months, with 55% saying they

5

Kowalski, R., et al. (2005, August) Electronic Bullying Among School-Aged Children and Youth. Presented at the annual meeting of the American

Psychological Association, Washington, DC

Kowalski, R., et al. (2005)

Fight Crime: Invest in Kids. (2006, August 17) 1 of 3 Teens and 1 of 6 Preteens Are Victims of Cyberbullying, News Release.

Wolak, J., Mitchell, K., & Finkelhor, D. (2006) Online Victimization of Youth: Five Years Later. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.

Kowalski, R., et al. (2005)

10

Burgess-Proctor, A., Patchin, J.W., & Hinduja, S. (2006, October) Cyberbullying: The Victimization of Adolescent Girls, www.cyberbullying.us

11

Burgess-Proctor, A., et al. (2006)

12

Kowalski, R., et al. (2005)

13

Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency. (2001, June) Addressing the Problem of Juvenile Bullying. Fact Sheet.

14

Borg, M.G. (1998) The emotional reactions of school bullies and their victims. Educational Psychology, 18(4), 433-444.

15

Willard, N. (2007)

CSBA Governance & POLICY SERVICES | policy briefs | July 2007

Schools need to be equally concerned about the health,

welfare and education of the students who are the

perpetrators of cyberbullying. These students have been

shown to suffer from many of the same psychological

and emotional difficulties as their victims such as

low self-esteem, anger and social isolation and to

exhibit other problem behaviors such as drinking alcohol

and performing poorly academically. There is also

evidence that these problem behaviors may carry over

into adulthood. One study found that 4 of every 10 boys

who bullied others as children had three or more legal

convictions by the time they turned age 24.16

2000) found that schools do have the authority to discipline

students when off-campus speech or behavior results in

a clear disruption of the classroom environment. In that

case, a student had been expelled for creating a Web site

that included threatening and derogatory comments about

specific school staff. Similarly, in Laycock v. Hermitage School

District (2006), a U.S. District Court found that a Web site

parody making fun of the principal in a non-threatening,

non-obscene manner was subject to discipline because it

did disrupt the educational program by requiring staff time

to resolve the problem and resulted in a shutdown of the

computer system.

Legal issues regarding

off-campus conduct

On the other hand, in Emmett v. Kent School District

No. 415 (2000), the U.S. District Court for western

Washington found that a students Web site with mock

obituaries of students and an online mechanism for

visitors to vote on who should die next did not actually

intend to threaten anyone and there was insufficient

evidence of school disruption. In Beussink v. Woodland

R-IV School District, a federal court in eastern Missouri

found that a students use of vulgar language to criticize

his school and its faculty on an off-campus Web site was

protected by the First Amendment because it was not

materially disruptive.

District policy pertaining to cyberbullying should

distinguish between bullying initiated on school campus

using district equipment and systems and bullying initiated

by students off campus during non-school hours. Districts

have the authority to monitor their own systems and to

take away computer privileges and impose discipline for

improper use. However, off-campus conduct raises First

Amendment concerns and requires a greater burden of

proof and caution regarding the imposition of discipline.

A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision may also impact a

districts ability to impose discipline for off-campus conduct.

In Frederick v. Morse, the court confirmed that a students

free speech rights are limited by the special circumstances

of the school environment and that a student could be

disciplined because his banner proclaiming Bong Hits 4

Jesus could be viewed as promoting illegal drug use, and

not merely offensive speech.

Education Code 48950 provides a free speech right

based on what a student may do outside of the school

environment. That is, if the off-campus speech or

communication is protected free speech, no discipline

may be imposed unless, pursuant to Education Code

48907, the expression is obscene, libelous or slanderous

or material which so incites students as to create a

clear and present danger of the commission of unlawful

acts on school premises or the violation of lawful school

regulations or the substantial disruption of the orderly

operation of the school.

The impact of these decisions on California schools is yet

to be determined. California law and the court decisions

are consistent in underscoring the importance for

districts to show that there is a nexus between the online

posting and disruption at school. They also highlight

the need to analyze whether language is more than just

offensive and is a true threat.

Discipline for off-campus cyberbullying has been largely

untested in the courts. Discussions about legal issues

pertaining to off-campus student speech usually cite

Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District.

In Tinker, the court clarified that school personnel have

the burden of demonstrating that the speech or behavior

resulted in a substantial interference with the educational

environment or the rights of others.

It is recommended that districts consult legal counsel

before implementing formal student discipline in cases

of off-campus conduct. Other types of response, such as

talking to the student who engaged in cyberbullying,

notifying his or her parents about the behavior, notifying

the Internet service provider or site, or contacting law

enforcement as warranted may still be implemented.

Although not binding on California school districts, a

Pennsylvania case (J.S. v. Bethlehem Area School District,

16

Banks, R. (1997) Bullying in Schools. ERIC Digest No. EDO-PS-97-17. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois.

CSBA Governance & POLICY SERVICES | policy briefs | July 2007

Policy considerations

Acceptable use of the districts technological

resources. Schools have a duty to exercise reasonable

precautions against cyberbullying using the districts

Internet system. Board policy, as well as the districts

Acceptable Use Agreement which students and their

parents should be required to sign as a condition of

using the districts technological resources, should

include an explicit statement that prohibits the use of

the districts system to bully or harass other students.

An explicit prohibition against cyberbullying calls

attention to the districts awareness of the problem and

may be necessary to initiate discipline in the event that

a student uses the districts system to harass another

student or staff member.

Board policy on cyberbullying may be considered in the

context of the districts overall approach to school safety,

with the goal of providing a positive school environment

that maximizes student learning. At the districts

discretion, strategies to address bullying, including

cyberbullying, may be incorporated into the districts or

school sites comprehensive safety plan.

Policy development on this issue may include opportunities

for input from district and/or school safety committees,

school site councils, students, parents/guardians, district

and site administrators, teachers, education technology

staff and other technology experts, classified staff,

community organizations and/or legal counsel.

Use of filters to block Internet sites. The district

may have already installed on district computers

a technology protection measure that blocks or

filters Internet access to visual depictions that are

obscene, child pornography or harmful to minors.

The effectiveness of these measures as a tool in

preventing cyberbullying has been called into question

and districts are cautioned not to over-rely on such

measures for these purposes. However, many districts

have blocked access to social networking sites, which

are sometimes used to send negative content to others.

CSBAs sample policy BP 5131 - Conduct has been

expanded to provide optional language which more

clearly prohibits cyberbullying and addresses the districts

response in the event that cyberbullying occurs. In

addition, BP/AR 6163.4 - Student Use of Technology

prohibits use of the districts online system to engage

in cyberbullying. Districts are encouraged to review

these materials and adapt them to meet their unique

circumstances. The district might also wish to review the

following related policies and administrative regulations:

BP/AR 0450 - Comprehensive Safety Plan, BP/AR 5145.12

- Search and Seizure (with respect to searches of students

personal property and district property under their

control), and BP 5145.2 - Freedom of Speech/Expression.

Supervision and monitoring of students

online activity. Reasonable precautions against

cyberbullying should include supervision of students

while they are using the districts online services.

Classroom teachers, computer lab teachers, library/

media teachers or other staff overseeing student use

of the districts online services should understand

their responsibility to closely supervise students

online activities. If teacher aides, student aides or

volunteers are asked to assist with this supervision,

they should receive training or information about the

districts policy on acceptable use.

As districts develop, review or revise policies or

administrative regulations related to cyberbullying, they

might consider the following issues:

Education of students, parents and staff.

Because cyberbullying often occurs away from

adult supervision, students must be informed about

the dangers of cyberbullying, what to do if they or

someone they know is being bullied in this way,

and the districts policy pertaining to appropriate

use of district technology and the consequences of

improper conduct. Instruction might also be provided

in the classroom or other school settings to explain

the legal limits of online speech and to promote

communication, resiliency, social skills, assertiveness

skills and character education.

In addition, districts have the right to monitor the use

of their equipment and systems. If a district receives

federal Title II technology funds or E-rate discounts,

it is obligated under 20 USC 6777 or 47 USC 254

to enforce the operation of technology protection

measures, including monitoring the online activities

of minors. Districts should discuss how such

monitoring will be accomplished, including whether

they wish to track Internet use through personally

identifiable Web monitoring software or other means.

Similarly, school staff and parents should be educated

on how to recognize warning signs of harassing/

intimidating behaviors and provided with effective

prevention and intervention strategies.

Maintenance and monitoring of the districts system

should be routine, technical and conducted by

appropriate staff. Some districts use intelligent

content analysis which monitors all Internet traffic

CSBA Governance & POLICY SERVICES | policy briefs | July 2007

and reports on traffic that has elements that raise a

reasonable suspicion. District staff can then review

those reports. Another technical approach allows for

real-time remote viewing of any computer monitor in

the building.

(with full e-mail headers) or pictures as evidence

rather than deleting them.

The investigation should include efforts to identify the

individual who is harassing the student. There may be

a way to track him or her through the Internet service

provider, even if the individual is using a fake name or

someone elses identity. If the district suspects that the

cyberbullying is criminal, local law enforcement may

be asked to track the individuals identity.

Students should understand that there is no

expectation of privacy and that use of the districts

system can be monitored. Clear notice of this fact

may deter improper activity.

The law regarding searches of an individual students

Internet use and computer files, even when there is

reasonable suspicion that a student has violated district

policy, is complex. Districts are advised to consult legal

counsel before conducting any such searches.

If it appears that the cyberbullying is initiated off

campus, it will be necessary to show that it has

substantially impacted school attendance or the

educational program in order for the district to impose

discipline on the student perpetrator (see section

Legal Issues Regarding Off-Campus Conduct above).

Thus, the investigation should also include processes

for assessing and documenting the impact of the

cyberbullying on students, staff or school operations.

Mechanisms for reporting cyberbullying.

Students should be urged to notify school staff,

their parents or another adult when they are being

cyberbullied, they suspect that another student is

being victimized, or they see a threat posted online.

Students need to understand that if a threat turns out

to be real, someone could be seriously hurt. However,

districts need to understand that students are often

reluctant to report to such incidents to an adult, in

part because they fear retaliation by the aggressor

or his or her friends. Thus, the district should

consider ways that students can confidentially and

anonymously report incidents.

Appropriate response to incidents of

cyberbullying. Existing school rules pertaining to

student discipline may be used in the event that a

student is found to have engaged in cyberbullying, or

the district may decide that other actions are needed

on a case-by-case basis. Depending on the seriousness

of the harassment, responses might include notifying

the parents of both the victim and perpetrator, filing a

complaint with the Internet service provider or social

networking site to have the content removed and/or

the students user privileges revoked, using conflict

resolution procedures, suspending or expelling the

perpetrator, and/or contacting law enforcement if the

behavior involves a threat of violence to a person, a

threat of damage to property, extortion, obscene or

harassing phone calls or text messages, stalking, a

hate crime, invading someones privacy by taking a

photo where there should be a reasonable expectation

of privacy, or sending sexually explicit images of

children or teens. The student perpetrator and his

or her parents should be informed of the potential

consequences to which they may be subjected,

including potential civil law liabilities.

Assessment of imminent threat. The

districts procedures for responding to a report of

cyberbullying should include processes to quickly

determine the legitimacy and imminence of any

threat. Often, what initially appears to be an online

threat may actually be meant as a joke or may be an

online fight (flame war) that is unlikely to result

in any real violence. But the highest priority is doing

what is necessary to protect against a possible real

threat, including notifying law enforcement as

appropriate. Students need to understand that adults

may not be able to tell if their language is a joke or

a threat, and that there are criminal laws against

making threats.

In addition, the district should consider ways it can

provide support to the victim through counseling or

referral to mental health services.

Investigation of reported incidents. Site-level

grievance procedures already in place for other types of

harassment (e.g., see AR 5145.3 - Nondiscrimination/

Harassment and AR 5145.7 - Sexual Harassment) may

provide an effective vehicle for reporting and handling

complaints of cyberbullying. The student who is being

victimized should be encouraged to not respond to the

cyberbullying and to save and print out the messages

CSBA Governance & POLICY SERVICES | policy briefs | July 2007

Resources

MySpace.com

This popular social networking site offers advice for

schools related to Internet safety in The Official School

Administrators Guide to Understanding MySpace and

Resolving Social Networking Issues.

CSBA

CSBAs Governance and Policy Services Department

issues sample board policies and administrative

regulations on a variety of topics related to school safety,

student conduct and technology. See www.csba.org.

CSBA also provides advisories and publications on related

topics, including Protecting Our Schools: Governing Board

Strategies to Combat School Violence.

National Resource Center for Safe Schools

A project of the Northwest Regional Educational

Laboratory, the Center offers technical assistance guides

to help schools sustain safe learning environments. See

www.safetyzone.org.

California Coalition for Childrens

Internet Safety

National School Safety Center

Offers a variety of school safety resources, including Set

Straight on Bullies which describes myths and realities

about bullying and strategies for educators. See www.

schoolsafety.us.

Partnered with the California Department of Consumer

Affairs, the Coalition includes state organizations such

as CSBA, business and education leaders, parent groups,

government agencies, law enforcement and community

organizations. Coalition activities are primarily focused

on keeping children safe from online predators but provide

useful information about Internet safety in general as well

as cyberbullying. See www.cybersafety.ca.gov.

U.S. Department of Education

The Office of Safe and Drug-Free Schools provides

resources on violence prevention. See www.ed.gov/about/

offices/list/osdfs/index.html.

California Department of Education,

Safe Schools

U.S. Department of Health Resources and

Services Administration (HRSA)

Provides information about key elements of an effective

bullying prevention program and resources to help

schools recognize bullying behavior and determine how

to respond, including its own comprehensive publication

Bullying at School. See www.cde.ca.gov/ls/ss.

Offers an activity guide, video toolkit, tips sheets and other

resources for its Stop Bullying Now! campaign. See

http://stopbullyingnow.hrsa.gov/adult/indexAdult.asp

U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention

Center for Safe and Responsible Internet Use

Includes information on Internet safety for children as

well as cyberbullying. See www.ojjdp.ncjrs.org.

Provides research and outreach services to address

issues of the safe and responsible use of the Internet.

Publications include Cyberbullying and Cyberthreats:

Responding to the Challenge of Online Social Aggression,

Threats and Distress and Cyber-Safe Kids, Cyber-Savvy Teens.

See http://csriu.org or www.cyberbully.org.

www.cyberbullying.us

An information clearinghouse for information on

cyberbullying.

Fight Crime: Invest in Kids

A national, nonprofit organization of more than 3,000

law enforcement leaders which conducts and analyzes

research to find out what works to prevent children from

turning to a life of crime. Provides resources and a model

bullying prevention program. See www.fightcrime.org.

CSBA Governance & POLICY SERVICES | policy briefs | July 2007

You might also like

- No More Victims: Protecting Those with Autism from Cyber Bullying, Internet Predators & ...From EverandNo More Victims: Protecting Those with Autism from Cyber Bullying, Internet Predators & ...No ratings yet

- CyberbullyingDocument6 pagesCyberbullyingmpusdNo ratings yet

- DEMOCRATS versus REPUBLICANS: Research on the Behaviors of High School StudentsFrom EverandDEMOCRATS versus REPUBLICANS: Research on the Behaviors of High School StudentsNo ratings yet

- Sexting, Texting, Cyberbullying and Keeping Youth Safe OnlineDocument7 pagesSexting, Texting, Cyberbullying and Keeping Youth Safe OnlineLucianFilipNo ratings yet

- CYBERBULLYINGDocument9 pagesCYBERBULLYINGRodolfo MondragonNo ratings yet

- "I'll Meet You Online:" A Look Into The Issue of CyberbullyingDocument8 pages"I'll Meet You Online:" A Look Into The Issue of CyberbullyingKelly ElizabethNo ratings yet

- The Perceptions of Cyberbullied Student - Victims On Cyberbullying and Their Life SatisfactionDocument7 pagesThe Perceptions of Cyberbullied Student - Victims On Cyberbullying and Their Life SatisfactionPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying: A Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesCyberbullying: A Literature ReviewAresNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying: Bullying Is Aggressive Behavior That Is Intentional and Involves An Imbalance of Power or StrengthDocument5 pagesCyberbullying: Bullying Is Aggressive Behavior That Is Intentional and Involves An Imbalance of Power or StrengthAamir WattooNo ratings yet

- Regular Exam Reading Passage - Cyberbullying and Its Influence On AcademicDocument5 pagesRegular Exam Reading Passage - Cyberbullying and Its Influence On AcademicSelma IilongaNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying on Social Media Among College StudentsDocument8 pagesCyberbullying on Social Media Among College StudentsLee HoseokNo ratings yet

- ELC560 Executive Summary (ES) Article SampleDocument5 pagesELC560 Executive Summary (ES) Article Sampleada legalNo ratings yet

- Cyber Safety Presentation For TeachersDocument46 pagesCyber Safety Presentation For Teachersshaikhassan777No ratings yet

- Impact of Cyberbullying on StudentsDocument16 pagesImpact of Cyberbullying on StudentsEmmanuel ChichesterNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying: A Study To Find Out How Online Bullying Affects The Academic Performance of Grade 12 StudentsDocument12 pagesCyberbullying: A Study To Find Out How Online Bullying Affects The Academic Performance of Grade 12 StudentsShen RondinaNo ratings yet

- Socially WiredDocument11 pagesSocially WiredKhen Mehko OjedaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document4 pagesChapter 2Ela Araojo Guevarra100% (1)

- Caribbean Studies Internal Assessment 2017Document39 pagesCaribbean Studies Internal Assessment 2017Kris84% (19)

- Cyberbullying and Self-EsteemDocument9 pagesCyberbullying and Self-EsteemDantrsNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying Among Young Malaysian Adults Factors of Gender, Age & Internet UseDocument3 pagesCyberbullying Among Young Malaysian Adults Factors of Gender, Age & Internet UseNurul Fatehah Binti KamaruzaliNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument1 pageResearch Paperapi-358892463No ratings yet

- 2hassessment2Document6 pages2hassessment2api-332411347No ratings yet

- International School Psychology: Cyberbullying in Schools: A Research of Gender DifferencesDocument15 pagesInternational School Psychology: Cyberbullying in Schools: A Research of Gender DifferencesPedro JVNo ratings yet

- CASE STUDY NI ChristanDocument10 pagesCASE STUDY NI ChristanChristian Buendia TorrejosNo ratings yet

- Multimodal EssayDocument6 pagesMultimodal Essayapi-583379248No ratings yet

- The Issue of Cyberbullying ofDocument10 pagesThe Issue of Cyberbullying ofkhent doseNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying in SchoolsDocument14 pagesCyberbullying in SchoolsOi LaNo ratings yet

- Basic Research 1Document4 pagesBasic Research 1JezenEstherB.PatiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper - Group 3Document37 pagesResearch Paper - Group 3Sophia Luisa V. DaelNo ratings yet

- Emailing Cyber BullyDocument5 pagesEmailing Cyber BullyniklynNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying CampaignDocument71 pagesCyberbullying CampaignAurelio ReyesNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying in Japan: An Exploratory StudyDocument22 pagesCyberbullying in Japan: An Exploratory StudyJhuniel BasilioNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying: How Physical Intimidation Influences The Way People Are BulliedDocument14 pagesCyberbullying: How Physical Intimidation Influences The Way People Are BulliedcoutridgeNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying Identification Prevention Response PDFDocument9 pagesCyberbullying Identification Prevention Response PDFcarolina.santiagoNo ratings yet

- Schools Must Lead Fight Against Growing Threat of CyberbullyingDocument10 pagesSchools Must Lead Fight Against Growing Threat of CyberbullyingDashka RamanavaNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying Effects on Student BehaviorDocument6 pagesCyberbullying Effects on Student BehaviorBosire keNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Cyber Bullying ThesisDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Cyber Bullying Thesisscongnvhf100% (1)

- Ojsadmin Paper 2Document18 pagesOjsadmin Paper 2Gian GarciaNo ratings yet

- Infedu 8 1 Infe136Document16 pagesInfedu 8 1 Infe136troy montarilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 SampleDocument8 pagesChapter 1 SampleSky SaracanlaoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper..Document25 pagesResearch Paper..ululkawNo ratings yet

- Brown (2014)Document10 pagesBrown (2014)FlorinaNo ratings yet

- Psychology Research PaperDocument21 pagesPsychology Research PaperAnkush ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Cyber-Bullying Among Criminal Justice and Public Safety Students of University of BaguioDocument32 pagesCase Study On Cyber-Bullying Among Criminal Justice and Public Safety Students of University of BaguioMark Dave Aborita MorcoNo ratings yet

- Social or Relational Aggression and the Role of Electronic MediaDocument3 pagesSocial or Relational Aggression and the Role of Electronic MediaJessy OoiNo ratings yet

- Smith Et Al-2008-Journal of Child Psychology and PsychiatryDocument10 pagesSmith Et Al-2008-Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatrywesley_wfNo ratings yet

- Short Research PaperDocument6 pagesShort Research PaperCrystal Queen GrasparilNo ratings yet

- Research QuestionsDocument3 pagesResearch QuestionsmadablinduNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying PaperDocument8 pagesCyberbullying PaperAlerie SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying PaperDocument8 pagesCyberbullying Papercourtneymvoss100% (2)

- Cyberbullying PaperDocument8 pagesCyberbullying PaperAlerie SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Cyberbullying - A Literature ReviewDocument19 pagesCyberbullying - A Literature ReviewPsychopath AestheticNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 36.81.137.101 On Tue, 22 Dec 2020 06:45:10 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 36.81.137.101 On Tue, 22 Dec 2020 06:45:10 UTCGrasiawainNo ratings yet

- Understanding Cyberbullying: Its Effects and FrequencyDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Cyberbullying: Its Effects and FrequencyMarie JhoanaNo ratings yet

- Adolescent - InternetDocument8 pagesAdolescent - InternetMadalinaPetrasNo ratings yet

- Yilmaz 2011Document10 pagesYilmaz 2011jatmiko.purwantonoNo ratings yet

- Anonymity Online Increases Cyberbullying Among AdolescentsDocument7 pagesAnonymity Online Increases Cyberbullying Among AdolescentsNadia MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Research Journal 1Document3 pagesResearch Journal 1Justin ByrdNo ratings yet

- CYBERBULLYINGDocument7 pagesCYBERBULLYINGFaisal BaigNo ratings yet

- All EscortsDocument8 pagesAll Escortsvicky19937No ratings yet

- Insecticide Mode of Action Classification GuideDocument6 pagesInsecticide Mode of Action Classification GuideJose Natividad Flores MayoriNo ratings yet

- Quatuor Pour SaxophonesDocument16 pagesQuatuor Pour Saxophoneslaura lopezNo ratings yet

- Final Revised ResearchDocument35 pagesFinal Revised ResearchRia Joy SanchezNo ratings yet

- CSEC English SBA GuideDocument5 pagesCSEC English SBA GuideElijah Kevy DavidNo ratings yet

- Pashmina vs Cashmere: Which Luxury Fiber Is SofterDocument15 pagesPashmina vs Cashmere: Which Luxury Fiber Is SofterSJVN CIVIL DESIGN100% (1)

- IkannnDocument7 pagesIkannnarya saNo ratings yet

- Practise Active and Passive Voice History of Central Europe: I Lead-InDocument4 pagesPractise Active and Passive Voice History of Central Europe: I Lead-InCorina LuchianaNo ratings yet

- Agile Process ModelsDocument15 pagesAgile Process ModelsShadrack KimutaiNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Analytics in Practice /TITLEDocument43 pagesFundamentals of Analytics in Practice /TITLEAcad ProgrammerNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting & ReportingDocument4 pagesFinancial Accounting & Reportingkulpreet_20080% (1)

- Building Materials Alia Bint Khalid 19091AA001: Q) What Are The Constituents of Paint? What AreDocument22 pagesBuilding Materials Alia Bint Khalid 19091AA001: Q) What Are The Constituents of Paint? What Arealiyah khalidNo ratings yet

- 5 Whys Analysis SheetDocument3 pages5 Whys Analysis SheetAjay KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Real Vs Nominal Values (Blank)Document4 pagesReal Vs Nominal Values (Blank)Prineet AnandNo ratings yet

- New Member OrientationDocument41 pagesNew Member OrientationM.NASIRNo ratings yet

- Foundations of Public Policy AnalysisDocument20 pagesFoundations of Public Policy AnalysisSimran100% (1)

- Westbourne Baptist Church NW CalgaryDocument4 pagesWestbourne Baptist Church NW CalgaryBonnie BaldwinNo ratings yet

- Apple Mango Buche'es Business PlanDocument51 pagesApple Mango Buche'es Business PlanTyron MenesesNo ratings yet

- NAS Drive User ManualDocument59 pagesNAS Drive User ManualCristian ScarlatNo ratings yet

- RITL 2007 (Full Text)Document366 pagesRITL 2007 (Full Text)Institutul de Istorie și Teorie LiterarăNo ratings yet

- A Model For Blockchain-Based Distributed Electronic Health Records - 2016Document14 pagesA Model For Blockchain-Based Distributed Electronic Health Records - 2016Asif KhalidNo ratings yet

- Visual AnalysisDocument4 pagesVisual Analysisapi-35602981850% (2)

- Fernando Medical Enterprises, Inc. v. Wesleyan University Phils., Inc.Document10 pagesFernando Medical Enterprises, Inc. v. Wesleyan University Phils., Inc.Clement del RosarioNo ratings yet

- 2020 Non Student Candidates For PCL BoardDocument13 pages2020 Non Student Candidates For PCL BoardPeoples College of LawNo ratings yet

- Terrestrial EcosystemDocument13 pagesTerrestrial Ecosystemailene burceNo ratings yet

- Keppel's lease rights and option to purchase land upheldDocument6 pagesKeppel's lease rights and option to purchase land upheldkdcandariNo ratings yet

- Financial Management-Capital BudgetingDocument39 pagesFinancial Management-Capital BudgetingParamjit Sharma100% (53)

- Student Worksheet 8BDocument8 pagesStudent Worksheet 8BLatomeNo ratings yet

- Land Securities Group (A)Document13 pagesLand Securities Group (A)Piyush SamalNo ratings yet

- Broken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.From EverandBroken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (43)

- Hell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryFrom EverandHell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Nicole Brown Simpson: The Private Diary of a Life InterruptedFrom EverandNicole Brown Simpson: The Private Diary of a Life InterruptedRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (16)

- Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIFrom EverandHearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansFrom EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- The Girls Are Gone: The True Story of Two Sisters Who Vanished, the Father Who Kept Searching, and the Adults Who Conspired to Keep the Truth HiddenFrom EverandThe Girls Are Gone: The True Story of Two Sisters Who Vanished, the Father Who Kept Searching, and the Adults Who Conspired to Keep the Truth HiddenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (36)

- The Franklin Scandal: A Story of Powerbrokers, Child Abuse & BetrayalFrom EverandThe Franklin Scandal: A Story of Powerbrokers, Child Abuse & BetrayalRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (45)

- The Gardner Heist: The True Story of the World's Largest Unsolved Art TheftFrom EverandThe Gardner Heist: The True Story of the World's Largest Unsolved Art TheftNo ratings yet

- If You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodFrom EverandIf You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1788)

- The Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalFrom EverandThe Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (101)

- The Last Outlaws: The Desperate Final Days of the Dalton GangFrom EverandThe Last Outlaws: The Desperate Final Days of the Dalton GangRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Double Lives: True Tales of the Criminals Next DoorFrom EverandDouble Lives: True Tales of the Criminals Next DoorRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- Swamp Kings: The Story of the Murdaugh Family of South Carolina & a Century of Backwoods PowerFrom EverandSwamp Kings: The Story of the Murdaugh Family of South Carolina & a Century of Backwoods PowerNo ratings yet

- Gotti's Rules: The Story of John Alite, Junior Gotti, and the Demise of the American MafiaFrom EverandGotti's Rules: The Story of John Alite, Junior Gotti, and the Demise of the American MafiaNo ratings yet

- Unanswered Cries: A True Story of Friends, Neighbors, and Murder in a Small TownFrom EverandUnanswered Cries: A True Story of Friends, Neighbors, and Murder in a Small TownRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (178)

- The Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's MenFrom EverandThe Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's MenRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (77)

- The Rescue Artist: A True Story of Art, Thieves, and the Hunt for a Missing MasterpieceFrom EverandThe Rescue Artist: A True Story of Art, Thieves, and the Hunt for a Missing MasterpieceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Reasonable Doubts: The O.J. Simpson Case and the Criminal Justice SystemFrom EverandReasonable Doubts: The O.J. Simpson Case and the Criminal Justice SystemRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (25)

- Our Little Secret: The True Story of a Teenage Killer and the Silence of a Small New England TownFrom EverandOur Little Secret: The True Story of a Teenage Killer and the Silence of a Small New England TownRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (86)

- To the Bridge: A True Story of Motherhood and MurderFrom EverandTo the Bridge: A True Story of Motherhood and MurderRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Beyond the Body Farm: A Legendary Bone Detective Explores Murders, Mysteries, and the Revolution in Forensic ScienceFrom EverandBeyond the Body Farm: A Legendary Bone Detective Explores Murders, Mysteries, and the Revolution in Forensic ScienceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (107)

- Cold-Blooded: A True Story of Love, Lies, Greed, and MurderFrom EverandCold-Blooded: A True Story of Love, Lies, Greed, and MurderRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (53)

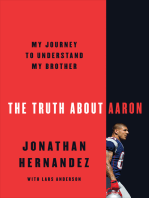

- The Truth About Aaron: My Journey to Understand My BrotherFrom EverandThe Truth About Aaron: My Journey to Understand My BrotherNo ratings yet

- The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has DeclinedFrom EverandThe Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has DeclinedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (414)

- A Special Place In Hell: The World's Most Depraved Serial KillersFrom EverandA Special Place In Hell: The World's Most Depraved Serial KillersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (52)