Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Justice of Ethic and Care - Litton

Uploaded by

api-302779030Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Justice of Ethic and Care - Litton

Uploaded by

api-302779030Copyright:

Available Formats

Justice, Care & Diversity

Part I

Foundations

Justice, Care & Diversity

Chapter 1

Justice and Care in Catholic Secondary Schools:

The Importance of Student-Teacher Relationships

Edmundo F. Litton

Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, California

Jason M. Stephens

University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut

It made a difference when you came to school sites. It showed

you cared, and made me care more.

Teachers at all levels have the power to impact the lives of their students. As the student

quoted above articulates in her evaluation of a professor in a Teacher Education program, caring

teachers not only affect those with whom they have direct contact but also the lives of those with

whom their students interact. In the life of this teacher candidate, a caring professor made a difference and she in turn, translated the care she received to the students she was teaching. Most

students are able to identify teachers who have made a difference in their lives. As they remember

a special teacher, many students would often talk about the way this teacher cared for them or

treated everyone fairly. Biographical accounts of just and caring teachers such as Jaime Escalante

(Matthews, 1988) and Lou Anne Johnson (Johnson, 1995) have made for good reading and

popular Hollywood films such as Stand and Deliver, Lean on Me, and Dangerous Minds to name

a few. By showing concern for students, earning their respect, and offering them opportunities for

intellectual and personal growth, these extraordinary teachers illustrate aspects of just and caring

teaching that can result in the improbable the academic engagement and achievement of students

who seemed destined to fail.

While biographies and dramas offer some insight into the meaning and power of good

teaching, such accounts often render an incomplete and sometimes simplistic and sensational

Justice, Care & Diversity

portrayal of justice and care in schools and classrooms. In this chapter, we will explore topics that

provide more depth into the meaning, practice and significance of just and caring teaching. What

does it really mean to be a just and caring teacher? Why are caring student-teacher relationships

important? What concrete practices can create more just and caring relationships in schools? We

believe these questions are important ones because a holistic education should not only foster

students intellectual development but also their personal, social and moral development. This

concept of a holistic education parallels the mission of Catholic schools of educating the whole

person. Educating the whole person means getting to know students on a personal level and

accepting the diverse backgrounds that all students bring into the classroom. To successfully

educate the whole person, teachers must be effective educators as well as ethical educators. In this

article, we will discuss how the concepts of justice, care, and a model of enlightened education can

be foundations for promoting diversity in Catholic schools. A truly just and caring education

encourages students to value their uniqueness.

Justice and Care

What does it mean to be a just and caring teacher? Educational philosophers often speak

of justice and care in school and classroom contexts as two distinct orientations. Justice is often

defined in terms of the fairness or equity with which scarce educational goods (e.g., school funds,

teacher time, student access to resources and even grades) are allocated and distributed. It aims to

respect individual rights and apply laws and policies impartially based on what one is due. Caring,

by contrast, is concerned with interpersonal relationships and how we might best nurture the

personal and social growth of each individual. It aims to build community and respond to all

members as distinct individuals. In short, where the ethic of justice pushes from sameness in treatment based on rights and principles, the ethic of care pulls for differentiation based on individual

needs and circumstances.

As noted by Noddings (1999) and others, moral pluralism allows for, even demands, both:

promoting one without the other justice without care or care without justice is inadequate. In

a classroom, for example, a teacher may promote justice by promoting high standards for all

learners. The lens of care, however, suggests the teacher needs to help each and every individual

student achieve those high standards, differentiating the curriculum or instruction to meet unique

needs and interests. Though distinct, justice and caring are often complementary. Care theorists

usually seek ends compatible with justice, but we try to achieve them by establishing conditions

in which caring itself can flourish (Noddings, 1999, p. 19).

Care, however, should not be romanticized as merely an individuals desire to make a

difference for another person. In thinking about responding to educational issues with care, educa-

Justice and Care in Catholic Secondary Schools

tors need to focus both on who is caring and the response of the person who is being cared for. For

example, as educators think about promoting high standards in a classroom, they need to be

constantly aware of how this action actually affects students. Are these caring actions really benefiting students? Students need to be part of the conversation so that any action that teachers take

are truly done with the students best interests in mind. Teachers need to get to know their students

if they truly want to take on the attitude of care. They cannot presume to know what students need.

Caring now refers properly to the relation, not just to an agent who cares and we must consider

the response of the cared-for (Noddings, 1999, p. 13).

Any caring relationship should be, as much as possible, without ulterior or hidden

motives. Blizek (1999) notes, caring is not just a matter of doing something, of acting in a particular way. It is also a matter of attitude (p. 97). True caring is done without any hidden agendas or

motives. In the end, true caring leads students to care even more for themselves, others, the environment, or ideas.

Caring is an important aspect of culturally responsive pedagogy (Jones, 2007). Culturally

responsive pedagogy incorporates the different microcultures of students in the teaching and

learning process (Martin and Litton, 2005). Jones (2007) states that caring is important to teaching

and learning because caring and acceptance allows [students] to feel safe and break down barriers

to taking necessary risks in the learning environment (p. 15).

Wentzel (1997) found that 8th grade students use dimensions similar to Noddings (1992)

conclusions when she talked about teacher caring and support. More specifically, teachers who

care were described as demonstrating democratic interaction styles, developing expectations for

student behavior in light of individual differences, modeling a caring attitude toward their own

work, and providing constructive feedback (Wentzel, 1997, p. 411). In a later study, Wentzel

(1998) found that supportive relationships with teachers to be a positive predictor of academic

effort, social responsibility and goal pursuit (e.g., sharing and helping in the classroom) in a

sample of sixth graders. More recent research by Murdock, Hale and Weber (2001) found that

middle school students perceptions of their teachers as competent, fair, and caring were powerful

(negative) predictors of their self-reported cheating (see also Stephens, 2004a; Stephens & Roeser,

2003). Similarly, Roeser, Midgley, and Urdan (1996) found significant relations between students

perceptions of their relationships with teachers and their sense of school belonging, which in turn

was related to their academic achievement.

Justice, Care & Diversity

Caring Student-Teacher Relationships

Studentteacher relationships are an important aspect of Catholic education. Due to the

emphasis on education of the whole person, teachers in Catholic schools take on additional roles

in their relationships with students in and out of the classroom (Cook, 2004, p. 66). Teachers have

multiple opportunities to nurture the whole person in their role as scholar, counselor, and role

model. Many Catholic school teachers view their occupation as a calling (Cook, 2004), one that

includes developing positive and nurturing relationships with students.

Many psychologists (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Deci & Ryan, 1985) have suggested that

such positive relationships greatly facilitate the adoption of community goals, values and norms.

Additionally, sociologists (e.g., Hirschi, 1989) have explained deviant behavior (such as cheating)

as the result of a weak or broken bond between individuals and society. Thus, establishing a positive student-teacher relationship may not only lead to positive outcomes for students it may also

mitigate negative ones. The social climate of an educational setting matters and students act more

positively when they perceive their teacher to be just and caring (Stephens & Roeser, 2003).

Furthermore, Stephens (2004) conducted research on student cheating and the results showed that

students were less likely to cheat in classes where their teachers were perceived to be fair and caring.

Attitudes and values of a teacher, even those that are implicitly stated, influence student

outcomes. Schools are perfect places for students to experience justice and care. Educational

settings should be places where students can begin to understand what it means to treat others with

justice and care that could be applied to other aspects of life (Noddings, 1999). In many instances,

students learn about justice and care through the hidden curriculum in the schools.

Jackson (1968) first proposed the concept of the hidden curriculum. Martin and Litton

(2005) describe the hidden curriculum as the values, beliefs, and messages educators present to

students, mostly in informal interactions that permeate the entire school culture. Justice and care are

aspects of the hidden curriculum that need to be explored in greater detail especially since Wentzel

(1997, 1998) demonstrates that pedagogical caring has a positive affect on learner outcomes.

10

Justice and Care in Catholic Secondary Schools

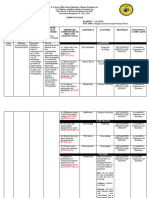

A Model of Enlightened Education

In order to create a more just and caring school environment, teachers must be both ethical

and effective as described in the model of Enlightened Education (Stephens, 2004b). This model

is illustrated in the following diagram:

Conceptual Model of Enlightened Education

(Stephens, 2004b)

Enlightened Education

Effective

Expert Knowledge1

human development

and learning

academic subject

matter

general and

domain-specific

teaching strategies

curriculum and

broader context

characteristics and

cultural background

of students

Ethical

Dispositions/Skills

reflective practitioner

effective problem

solvers

engaged members

of the learning

community

valuing learning

(continued

professional

development)

Just

clear learning objectives

and grading criteria

reasonable assignments

open dialogue and due

process

fair and equal treatment

of all learners

unbiased grading

policies and procedures

involvement of students

in decision-making

Caring

safe environment

open trust of and

concern for students

interest in and

support of personal

growth

inclusive sense of

belongingness

respect, appreciation,

and celebration of

student differences

individual treatment

Adapted from Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations for the new reform. Harvard

Educational Review, 19(2), 4-14.

Research shows that effective teachers are reflective practitioners who know the theoretical foundations behind their subject matter and practice. Effective teachers also integrate their

students cultural experiences in lessons. There are certain teacher characteristics that are

perceived to be just and caring (e.g., having high expectations for all students).

Brophy (1986) states that teachers who do not have a strong knowledge base of teaching

often make instructional decisions based on untested theories or personal experiences. While

teachers may have anecdotal information based on their personal experiences as learners, justice

and care are components that need to be tested so that teachers truly understand how these two

dimensions of an enlightened education influence learning outcomes and student behavior.

11

Justice, Care & Diversity

Teaching is both an art and an applied science anda validated knowledge base, if used properly, should benefit practitioners without inappropriately constricting their creativity or professionalism (Brophy, 1986, p. 1075).

Steps Towards Creating a Just and Caring Environment

Creating a just and caring community often requires a paradigm shift. In a study involving teacher

interviews, Litton (2006) found that many Catholic school teachers believe in the concept of caring

and stated that they cared for their students, but they had a difficult time expressing this care.

Many of these teachers associated caring with being soft and they feared that students would

take advantage of their caring behavior. These teachers also acknowledged that caring often means

having to differentiate instruction for some students. Despite this belief that it was necessary to do

different things for students based on student needs, differentiated instruction was often associated

with lowering standards.

A model of enlightened education is neither about being lenient to students or lowering

standards. Caring relationships affirm students and allow them to care for themselves and others

even more. Caring communities in school can be created through various means:

Begin a dialogue with students on what they believe it means to be cared for by teachers.

How do students perceive fairness? How do students define effective teaching?

Allow students to take ownership of the school (Noddings, 1992). Encouraging student

participation in decisions that affect the entire school community helps students see that

the school is their responsibility. Student government is one of the best ways to

encourage student engagement in school decisions (Power & Makogonm, 1995).

Give students the opportunity to practice caring in school (Noddings, 1992). Many

Catholic secondary schools provide opportunities to practice caring through community

service.

Create theme-based lessons and units that allow students and teachers to explore

curriculum together. Constructivist-based learning environments foster student-teacher

relationships by honoring prior knowledge and lived experiences, and by distributing

expertise and shared responsibility for learning. Students will also feel more responsible

for their own learning.

Openly discuss issues that confront the classroom or school community. Do not allow

perceptions of racism, homophobia, classicism, ableism, or sexism to exist in a school.

Handled appropriately, these unfortunate manifestations of ignorance, intolerance and

fear can become rich teachable moments (See Colby, Ehrlich, Beaumont, & Stephens,

2003 for examples).

12

Justice and Care in Catholic Secondary Schools

Examine the curriculum and create benchmarks that students must achieve. Set high

standards and use differentiated instruction (including culturally relevant pedagogy) to

help each student reach these high standards.

Working towards just and caring communities requires the transformation of institutions.

Some scholars (e.g., Noddings, 1992) advocate the end of competitive grading. While many

Catholic secondary schools may want to move cautiously as they transform their institutions,

change does need to take place if students do not feel cared for. Every school will need to evaluate

the response for creating a just and caring community. But it is clear that trusting relationships

between students and teachers need to be maintained and developed in an atmosphere where many

students distrust authority. However, if teachers truly recognize the unique gifts of the individual

students in their classroom and celebrate these gifts, the students will feel cared for and positive

things will happen.

Knowing that the teacher cares about me is the difference when

I know the answer for sure and raising my hand when I think I

know the answer. But I know for sure that if I answer wrong,

Ms. Smith will still like me and think I am smart.

An 8th Grade Student (Jones, 2007, p. 15).

Questions for Discussion

1. In your work as a teacher or administrator, what do you do on a daily basis to

develop a just and caring relationship with your students?

2. How do you balance justice and care in your educational practice?

3. Examine the mission statement of your school. How can the concepts of justice

and care be more fully integrated in the mission statement of your school?

4. Look back at your own educational experiences as a student. Who of your past

teachers would you consider just and caring? Why?

13

Justice, Care & Diversity

References

Blizek, W. L. (1999). Caring, justice, and self knowledge. In M. S. Katz, N. Noddings & K. A. Strike

(Eds.), Justice and caring: The search for common ground in education (pp. 93-109). New York:

Teachers College Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Alienation and the four worlds of the child. Phi Delta Kappan, 46, 430-436.

Brophy, J. (1986). Teacher influences on student achievement. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1069-1077.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Alienation and the four worlds of the child. Phi Delta Kappan, 46, 430-436.

Colby, A., Ehrlich, T., Beaumont, E., & Stephens, J. M. (2003). Educating citizens: Preparing Americas

undergraduates for lives of moral and civic responsibility. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cook, T. (2004). Teachers. In T. C. Hunt, E. A. Joseph, & R. J. Nuzzi (Eds), Catholic schools still make a

difference (pp. 57-72). Washington, DC: National Catholic Educational Association.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York:

Academic Press.

Hirschi, T. (1989). A control theory of delinquency. In D. H. Kelly (Ed.), Deviant Behavior: A text-reader

in the sociology of deviance (pp. 178-186). New York: St. Martins Press.

Johnson, L. (1995). Dangerous minds. New York: St. Martins Press.

Jones, S. J. (2007). Culturally responsive instruction. Leadership 37(2), 14-17,36.

Litton, E.F. (2006). Caring and teaching. Unpublished manuscript, Loyola Marymount University, Los

Angeles, CA.

Martin, S. P. & Litton, E.F. (2004). Equity, Advocacy, and Diversity: New directions for Catholic schools.

Washington, DC: National Catholic Educational Association.

Manning, R. C. (1999). School vouchers in caring liberal communities. In M. S. Katz, N. Noddings & K.

A. Strike (Eds.), Justice and caring: The search for common ground in education (pp. 113-126).

New York: Teachers College Press.

Mathews, J. (1989). Escalente: The best teacher in America. New York: Henry Holt & Co.

Murdock, T. B., Hale, N. M., & Weber, M. J. (2001). Predictors of cheating among early adolescents:

Academic and social motivations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 96(1), 96-115.

Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Noddings, N. (1999). Care, justice, and equity. In M. S. Katz, N. Noddings & K. A. Strike (Eds.), Justice

and caring: The search for common ground in education (pp. 7-20). New York: Teachers

College Press.

Power, C., & Makogonm, T. A. (1995). The Just Community Approach to Care. Journal for a Just and

Caring Education, 2(9-24).

14

Justice and Care in Catholic Secondary Schools

Roeser, R. W., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. C. (1996). Perceptions of the school psychological environment

and early adolescents psychological and behavioral functioning in school: The mediating role of

goals and belonging. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 408-422.

Stephens, J. M. (2004a). Just cheating? Motivation, morality and academic (mis)conduct among adolescents. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Stephens, J. M. (2004b). Toward an enlightened education: The effective and ethical dimensions of good

teaching. Unpublished manuscript, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT.

Stephens, J. M., & Roeser, R. W. (2003, April 25). Quantity of motivation and qualities of classrooms: A

person-centered comparative analysis of cheating in high school. Presented at the Annual

Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago.

Wentzel, K. (1997). Student motivation in middle school: The role of perceived pedagogical caring.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 3, 411-419.

Wentzel, K. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers,

and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 2, 202-209.

15

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Documentation in Psychiatric NursingDocument15 pagesDocumentation in Psychiatric NursingShiiza Dusong Tombucon-Asis86% (7)

- Drill Procedures Quick GuideDocument1 pageDrill Procedures Quick Guideapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Dance Chaperones Expectations 2018Document1 pageDance Chaperones Expectations 2018api-302779030No ratings yet

- Seconds Count Newsletter Final DraftDocument4 pagesSeconds Count Newsletter Final Draftapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Rigor Relevance FrameworkDocument8 pagesRigor Relevance Frameworkapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Google Classroom Cheat SheetDocument6 pagesGoogle Classroom Cheat Sheetapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Google Drive Quick Reference GuideDocument4 pagesGoogle Drive Quick Reference Guideapi-302779030100% (2)

- Warm Demander ArticleDocument7 pagesWarm Demander Articleapi-302779030No ratings yet

- 9-10 Standards UnpackedDocument41 pages9-10 Standards Unpackedapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Dok ChartDocument1 pageDok Chartapi-302779030No ratings yet

- CC Anchor StandardsDocument1 pageCC Anchor Standardsapi-302779030No ratings yet

- 11-12 Standards UnpackedDocument41 pages11-12 Standards Unpackedapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Pma Bellschedule 2016 Rev071716 MainDocument2 pagesPma Bellschedule 2016 Rev071716 Mainapi-302779030No ratings yet

- CoursefeedbackDocument12 pagesCoursefeedbackapi-302779030No ratings yet

- Ca Teaching StandardsDocument1 pageCa Teaching Standardsapi-302779030100% (2)

- Language Analysis - Functional Language: Making A SuggestionDocument2 pagesLanguage Analysis - Functional Language: Making A Suggestionhossein srNo ratings yet

- Mark Scheme (Results) November 2020: Pearson Edexcel International GCSE Mathematics A (4MA1) Paper 2HDocument21 pagesMark Scheme (Results) November 2020: Pearson Edexcel International GCSE Mathematics A (4MA1) Paper 2HSteve TeeNo ratings yet

- Duncan Clancy ResumeDocument1 pageDuncan Clancy Resumeapi-402538280No ratings yet

- ENG03Document2 pagesENG03Fatima SantosNo ratings yet

- Improve Your Communication Skills: Ghulam Mustafa KhattiDocument21 pagesImprove Your Communication Skills: Ghulam Mustafa KhattiGhulam MustafaNo ratings yet

- WMS - IV Flexible Approach Case Study 2: Psychiatric DisorderDocument2 pagesWMS - IV Flexible Approach Case Study 2: Psychiatric DisorderAnaaaerobiosNo ratings yet

- Chem Books AllDocument4 pagesChem Books Allpmb2410090No ratings yet

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World (Q1 Wk5)Document22 pages21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World (Q1 Wk5)Marc Vryant De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Masouda New CVDocument4 pagesMasouda New CVmasoudalatifi65No ratings yet

- Ncert Exemplar Math Class 11 Chapter 11 Conic-SectionDocument33 pagesNcert Exemplar Math Class 11 Chapter 11 Conic-SectionDhairy KalariyaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Teaching PE Health in Elem. Updated 1Document10 pagesModule 1 Teaching PE Health in Elem. Updated 1ja ninNo ratings yet

- HR Executive Interview Questions and AnswersDocument2 pagesHR Executive Interview Questions and AnswersRaj SinghNo ratings yet

- TOEFL Writing PDF PDFDocument40 pagesTOEFL Writing PDF PDFFaz100% (1)

- Final English 7 1ST QuarterDocument4 pagesFinal English 7 1ST QuarterRosel GumabatNo ratings yet

- Agoraphobia 1Document47 pagesAgoraphobia 1We Are HanakoNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Comm3311.002.07s Taught by Shelley Lane (sdl063000)Document7 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Comm3311.002.07s Taught by Shelley Lane (sdl063000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- How To Write A CV in EnglishDocument9 pagesHow To Write A CV in EnglishenkeledaNo ratings yet

- How To Solve A Case StudyDocument2 pagesHow To Solve A Case StudySaYam ReHania100% (1)

- Resume 2021 RDocument3 pagesResume 2021 Rapi-576057342No ratings yet

- Ict Management 4221Document52 pagesIct Management 4221Simeony SimeNo ratings yet

- Commerce BrochureDocument3 pagesCommerce BrochureSampath KumarNo ratings yet

- Job Application Letter in PakistanDocument7 pagesJob Application Letter in Pakistanfsv06ras100% (1)

- Nutritional Status of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asds) : A Case-Control StudyDocument14 pagesNutritional Status of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asds) : A Case-Control StudyyeyesNo ratings yet

- Lab 1 - Intro To Comp ProgramsDocument11 pagesLab 1 - Intro To Comp Programssyahira NurwanNo ratings yet

- NRS110 Lecture 1 Care Plan WorkshopDocument14 pagesNRS110 Lecture 1 Care Plan WorkshopsamehNo ratings yet

- Tools and EquipmentDocument5 pagesTools and EquipmentNoel Adan CastilloNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 RevisedDocument7 pagesChapter 1 RevisedChristian PalmosNo ratings yet

- SHRM ReviewDocument18 pagesSHRM ReviewjirnalNo ratings yet

- Gr5.Mathematics Teachers Guide JPDocument149 pagesGr5.Mathematics Teachers Guide JPRynette FerdinandezNo ratings yet