Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1197 0

Uploaded by

Luis Gómez Castro0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views16 pagesKSG

Original Title

1197_0

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentKSG

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views16 pages1197 0

Uploaded by

Luis Gómez CastroKSG

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 16

Case Program €16-93-1197.0

Kennedy School of Government

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project

In 1989, officials in the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) began

laying plans for a pilot project that would alter the way the department carried out its inspection and

‘enforcement responsibilities in the state. Instead of scrutinizing a firm’s air, water, and hazardous

‘waste controls separately, inspectors participating in the pilot would conduct “cross-media” inspections

that would encompass the entire facility in one visit, enabling them to take a comprehensive look at its

inputs, processes, and outputs (including pollution). Such whole facility, cross-media inspections were

designed to avoid the pollution “shell game,” whereby compliance with regulations in one medium not

infrequently created a pollution problem in another.

More ambitiously, DEP officials hoped to make cross-media inspections a tool for implementing,

‘a new approach to environmental protection that had been gaining currency among environmentalists

and regulators in recent years: pollution prevention. Instead of controlling pollution by treating the end.

point of industrial processes, advocates argued, regulators should also seek to reduce the amount of

pollution generated in the first place. Cross-media inspections could help achieve that aim by

‘acquainting inspectors with the full range of a facility's production system: the reports and enforcement,

actions that followed would emphasize steps that businesses could take—with the aid of free

technical assistance from another state agency—to cut down an the use of toxic substances and the

‘generation of polluting wastes.

Dut the implementation of a whole facility, cross-media inspection strategy would mean

‘wrenching the DEP out of practices that had been in place, and finely honed, over two decades.

Frontline and supervisory inspectors had typically devoted their careers to mastering the complex

scientific and technical issues and the equally complex web of federal and state law for a medium-

specific program, such as air, water, or hazardous waste, They were skeptical of the notion of a “super

inspector” who would master the intricacies of all the programs. Moreover, the media programs had no

‘experience in cooperative ventures: they had operated independently of each other, maintaining

separate inspection routines and files.

Overseeing the development and implementation of an operational plan for the project would

be the responsibility of Patricia Deese Stanton, newly appointed assistant commissioner of the recently

‘created Bureau of Waste Prevention. Stanton came to her job from DEP's Division of Water Supply in

the aftermath of a reorganization instituted by DEP Commissioner Daniel Greenbaum. The

reorganization had brought the media programs under the waste prevention umbrella (see Exhibit 1),

but as a practical matter, they continued to operate separately in DEP's central office and in its four

regional offices, which carried out the frontline work of inspection and enforcement. As the first person.

to occupy the waste prevention post, Stanton would have to find a way to make these programs work

This case was written by Esther Scott for Michael Barzelay, Associate Professor of Public Policy, for

the Program on Innovations in State and Local Government, John E. Kennedy School of Government.

Funding for the case was provided by the Ford Foundation. (0393)

Copyright © 1993 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project C16-93-1197.0

together in the pilot. It would not be an easy task. Beyond top management and policy officials in DEP

hheadquarters in Boston, there was only a modicum of support for the project, especially in the field. “I

Used to joke,” she recalls, “[that] when the ... pilot was conceived there were probably—t'm not

exaggerating—maybe six people in the agency who thought it was a remotely viable idea.”

Source Reduction in Massachusetts,

The idea of reducing the amount of waste generated—known variously as source reduction,

‘waste minimization, waste prevention, and pollution prevention—grew out of dissatisfaction with the

focus on control or treatment as the primary tool of environmental regulation. It surfaced in the mid-

1980s, at a time, says Patricia Deese Stanton, when gains from control technology had slowed to a costly

trickle, “We had done the #0 percent that was easy” through pollution control devices, she says, “and

the last 20 percent was very expensive. ... We had gotten as many of the improvements that we could

Set with that strategy, and then we really needed to take a different strategy.” The new tack, Stanton

continues, sought to change the regulatory focus, as embodied in federal law, from one that dictated

“where you dump stuff” to one that asked “do we need to create this stuff in the first place?” By the

end of the decade, waste prevention was, says Daniel Greenbaum, “emerging ... in the national

environmental agenda,” and had won the notice of William Reilly, EPA administrator in the Bush

administration. In 1990, pollution prevention would be defined and codified in federal law as a

Priority for the agency.

In Massachusetts, pollution prevention got an early start in the Department of Environmental

Management (DEM), a “sister” agency in the state Environmental Affairs Secretariat which managed

the state's forests, parks, recreation facilities, and watersheds. Since the early 1980s, DEM’s Bureau of

Solid and Hazardous Waste, under the direction of James Miller, had been running workshops and

‘conferences on source reduction and hazardous waste managemnent—an outgrowth in part of the

department's responsibility for siting hazardous waste facilites in the state. In 1986, Miller and some

‘of his staff migrated over to the Division of Solid Waste Management in DEP—or the Department of

Environmental Quality Engineering (DEQE), as DEP was then called. (ee Appendix A for background

on DEQE/DEP.) Miller let behind a small technical assistance unit in DEM—the Office of Safe Waste

Management. That same year, the staff at Safe Waste Management launched a pilot program in

southeastern Massachusetts to provide on-site technical assistance in source reduction to the jewelry

plating industry, which produced a high volume of toxic wastes in all media. The project did not

include any participation by DEQE—a reflection of the two agencies’ differing roles. DEM or, more

precisely, the Office of Safe Waste Management viewed its mission in strictly service terms; it had no

interest, says Tim Greiner, an engineer in the office at the time, in being “the eyes and spies” of a

regulatory authority.

‘Meanwhile, over at DEQE, Miller had followed up on his interest in pollution prevention by

creating three staff positions that would be dedicated to hazardous waste source reduction. In time,

‘hat number shrank to one, but the remaining staff member—Manik “Nikki” Roy, then a PhD

candidate at the Kennedy School of Government—stayed on, eventually assuming the title of source

seduction policy coordinator. It was Roy who combined a source reduction approach with the idea of

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project______C16-93-1197.0

«ross- or multi-media inspections and planted the seeds for the pilot program that ultimately became

Innowmn as the Blackstone Project

The Emerging Idea. As Roy recalls, it was while working on a source reduction project in the

plastic coating industry—at the suggestion of Kenneth Hagg, then deputy commissioner at DEQE and an

early proponent of waste prevention—that he realized that “at DEQE we had a net that was full of

holes.” AA review of 50 companies revealed that many of them were known to only one regulatory

rogram, and some were not known at all. At the same time, he took note of the problem of “media

transfers,” whereby polluting waste was shifted from one medium to another. Sometimes this was done

by a company in order to avoid coming under regulatory control. For example, Roy explains, “if you were

a hazardous waste generator, you would be insane fo manifest that waste [.e, report and dispose of it

according to regulations}. You'd be much smarter to dump it down the sewer”—taking advantage of the

often weak regulatory management of many sewage treatment plants at the time. Ifa company was

being inspected in only one medium, moreover, it would be relatively easy to get away with such

behavior. Patricia Deese Stanton points to the example of a firm that was discharging a highly toxic

‘chemical through a hole in the floor, where it ended up in the groundwater supply; the facility was

inspected annually, but only by an inspector from the air quality program. The company “just didn’t tell

anybody” about the discharge, she says, “and nobody happened to notice’

‘At other times, however, the media transfer was the unintended result of end-of-the-pipe

environmental controls, whereby regulators found themselves caught in what Douglas Fine of the

department's Central Regional Office called a “pollution shell game.” Thus, for example, installing a

serubber, which used water to remove smokestack pollutants, would create a new pollution problem in

the form of contaminated water; applying treatment technologies that would settle the contaminants

‘out of the water would leave behind a hazardous waste in the form of sludge, which would then have

‘to be incinerated or disposed of in a landfill! The end result, says Greenbaum was the “perception”

that regulators were simply “pushing pollution around.”

Eventually, Roy concluded that both source reduction and the media transfer problem could be

addressed in a program of cross-media, whole facility inspections. Under this scheme, an inspector or a

‘team of inspectors would examine the entire facility, singly or in groups, and identify all of the

emissions and discharges from a plant's industrial processes. Any enforcement actions that resulted

from the inspections would be slanted in the direction of source reduction. Businesses would be

‘encouraged to come into compliance less through control technologies than through changes in thelr

production processes that would reduce the amount of pollutants they used. Such a program would

include an offer of free technical assistance from a separate state agency to companies that needed

advice and information in rethinking and retooling their operations.

With Hagg’s encouragement, Roy put these ideas into an internal memorandum, dated March 2,

1987, proposing a “comprehensive source reduction pilot program."2 “The proposal basically said,” he

1 Douglas Fine, “Where Everybody Wins," Worcester Businest Journal, April 27-May 10, 1992, p. 29.

2 The scheme took the form of a pilot, sccording to Roy, becavse he bad initially put the proposal together io

response to anticipated funding from the state legislature for research om source reduction, The funding never

‘trialized, but Roy retained the format for bis DEQE propel.

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project___C16-93-1197.0

recalls, “that we ought to put together a team of air, water, and hazardous waste inspectors, and a

team of technical assistance people, and focus them on the same industry, with the charge of making

sure that there is environmental protection across all media within that industry, and advising that

industry towards pollution prevention.” That same month, Hagg convened a meeting of the directors of

DEQE's four regional offices to discuss the proposal. As Roy recalls, “They all said, ‘Well, it sounds

like an interesting idea, but weneed to have a bunch of questions answered about it” Roy's efforts to

«all together a follow-up meeting to review his answers to those questions, however, proved fruitless.

“Tfelt Iwas just being given the runaround,” he says. “ ... It was clearly not a top priority for them.”

Hagg would not, however, let the idea fade away. In July 1987, he organized a Source

Reduction Policy Advisory Committee, chaired by Nikki Roy, to come up with recommendations for

promoting source reduction. Committee membership consisted of representatives from DEQE’s major

regulatory programs—air, water, hazardous waste, and solid waste—along with Barry Fogel, director

of the Central Regional Office, who represented the regions. When the committee came out with its

findings in early 1988, it strongly endorsed, among other things, the principle of cross-media, whole

facility inspections.3 But while pleased with the outcome, Roy also felt impatient with the delay.

“The main thing that the committee did,” he maintains, “beyond endorsing the general concept, was to

put the [pilot] project on hold fora year. It took me out of a project-moving mode ... and into a study and

group management mode.”

‘A mode shift was in the offing for Roy, and forall of DEQE, however. In May 1988, Governor

Michael Dukakis named Daniel Greenbaum as the new commissioner of the department. Greenbaum,

formerly vice president for public policy and strategic planning at the Massachusetts Audubon Society,

‘was coming in with ambitious plans to revamp the organization and its regulatory orientation. The

word was, Roy recalls, that “among other things, Dan wanted to make a big jump on a lot of issues,

including source reduction.”

Overhauling DEQE

Greenbaum came to the department at a time when it, and other state agencies with

environmental responsibilities, had become the subject of “scathing criticism” from the Massachusetts

legislature and envvironmentalists. In its FY 1988 budget, the State Senate Ways and Means Committee

had inserted language creating a commission to investigate these agencies and make recommendations

for steps they could take to improve thelr operations. The commission, chaired by former US Senator

Paul Tsongas, completed a draft report ust as Greenbaum was about to assume his new duties at DEQE.

‘The report concluded, among other things, says Greenbaum, that DEQE did “not have a clear sense of

mission, ... did not have a proactive sense of moving out to prevent pollution. It was too much involved

in reacting to clean up problems after the fact.” While environmental groups “distrusted” the

department, Greenbaum continues, the “business community had serious concems” as well. These

concerns focused largely on the “massive backlog” of permitapplications, but there was unhappiness

3 The commitee also proposed a pilot project in cross-media permitting. In addition, it recommended incorporating

source reduction incentives in all new regolations a proposal that Hage, then the acting commissioner of DEQE,

ordered to be implemented that March.

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project, C16-95-1197.0

over inspections as well. The staff at DEQE was considered arrogant and frequently adversarial.

Small firms in particular shrank from contact with the agency. DEQE was “a dirty word,” says

Jonathan Brunell, president of a small, 100-year-old, family-owned electroplating company in

Worcester. “We didn’t want to see them, and we hoped that they never saw us.” Companies like

Brunell’ hesitated to seek DEQE’s help on environmental problems, he told the Worcester Business

Journal, because ofits regulatory role. “I would be afraid to call the department," he said, “for fear of

being inspected.”

‘Among the remedies the Tsongas commission proposed in its report was the recommendation

that the department restructure its operations to stress pollution prevention, and rename itself the

Department of Environmental Protection. Is original name had left “a perception among some,”

Greenbaum explains, “that [the agency] seemed to have the mission of [finding] engineering answers,

‘which may not be protective.” Even while the commission was putting the final touches on its report,

Greenbaum (who had met several times with commission members) was doing the same with a

reorganization of DEQE, which was formally announced in September 1988,

‘The reorganization that Greenbaum fashioned was intended both to streamline and integrate

DEQE’s programs, and to highlight the priorities he had articulated soon after arriving at his new

(Post: resource protection and waste prevention. ‘The key changes took place in the bailiwick of the

deputy commissioner for policy and program development, where three new bureaus were created, each

to be headed by an assistant commissioner; a parallel structure would be put in place in the regional

offices, with each bureau overseen by a regional engineer. The three new bureaus, says Patricia Deese

‘Stanton, could be broadly characterized as “past sins” (Bureau of Waste Site Cleanup), “present sins”

(Bureau of Waste Prevention), and “future sins” (Bureau of Resource Protection). Putting them together,

Greenbaum recalls, entalled “major wrestling” within the department, as the divisions and smaller

‘units were reshuifled to fit the guiding mission of each bureau, Under the Bureau of Waste Prevention,

for example, Greenbaum wanted to lump together “all of te programs that regulate any kind of waste

product from industry.” Accordingly, he took the industrial wastewater program, a small unit of about

seven employees which primarily did permitting, out of the Water Pollution Control Division (in the

Bureau of Resources Protection) and moved it into the waste prevention bureau, “giving it a new, higher

priority.”"+

By the end of 1988, the reorganization was in place, and DEQE was now DEP. In the meantime,

while these changes were taking place, Nikki Roy's source reduction pilot was being rescued from the

dustbin of policy recommendations and given new prominence in the department

‘The Blackstone Project Is Born

In the months since his Source Reduction Advisory Committee had made its recommendations,

‘ikki Roy had pressed on with his proposal for a pilot multimedia inspection program. In May 1988,

4 In Massachusetts, the chief role in wastewater regula

facilities (often referrd to as publicly owned sewage ‘reatment works, of POTWs), to whom EPA delegsied

regulatory and enforcement euthority for discharges to their sexe systems; DEQE in tara regulated the POTWs for

‘their discharges and/or incinerstor emissions,

Fell to municipal and regional wastewater treatment

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project. €16-93.1197.0

‘he applied for $300,000 in EPA funds, under a new grant program in waste minimization, with $100,000

of the money to go to DEM to provide technical assistance. At the same time, however, Kenneth Hagy,

‘who had stayed on as deputy commissioner, had brought the pilot program, along with the other

Proposals of the advisory committee, to Greenbaum’s attention, Together, says Greenbaum, they

decided to pursue the pilot project in cross-media inspections as a source reduction opportunity. “Our

bias was clearly action-oriented,” Greenbaum recalls. “... We didn’t want to spend a lot of time having

another committee look into how to do this.” Accordingly, in July, the new commissioner announced

‘hat, regardless of EPA’s decision on Roy's application, the department would proceed with the pilot.

When, the following month, the grant request was tumed down,5 Greenbaum went ahead and funded

‘two staff positions for the as yet unnamed project.

Outside funding was in the offing, however. In September 1988, DEM applied for funds froma

different EPA grant program to extend its technical assistance project in source reduction to metal-

intensive industries in central Massachusetts, Unlike its southeastern Massachusetts project, in which

the old DEQE had played no role, this time DEM included provisions for working with a DEP pilot

inspection program. Specifically, DEM proposed that DEP would set up a multimedia inspection pilot

Within the central Massachusetts project aree; DEM, through its Office of Safe Waste Management,

‘would coordinate its technical services with firms inspected under the pilot “in order to determine the

effectiveness of non-regulatory assistance in the context of regulatory attention.” Under this

arrangement, DEP inspectors would refer companies, particularly those that were out of compliance, to

DEM’s Office of Safe Waste Management for technical assistance, and the DEM unit would give these

referrals priority. This unprecedented alliance with DEP had grown out of discussions between Nikki

Roy and his counterparts at the Office of Safe Waste Management. Out of those conversations, says

Tim Greiner, a staff member with the Safe Waste Management unit, had come an agreement that DEP

‘would focus its pilot program on metal-intensive businesses s0 that the Office of Safe Waste

‘Management could train inspectors in source reduction techniques in that industry; that DEP would

select “a sensitive ecosystem” as its pilot locale; and that DEP would find a regional director “willing

to have such a pilot project in their area.”

‘The last of these stipulations did not prove easy to do, according to Patricia Deese Stanton

(who arrived at her assistant commissioner post some months later). Ken Hagg, she says, “tried to

‘muscle the four regional [directors] to get one of them to agree to do this.” Eventually, Barry Fogel,

director of the Central Regional Office in Worcester came forward—the only regional chief who

‘offered to serve as host to the pilot. Fogel’s acquiescence appeared to be a combination of pragmatism—

his office would get new staff slots as a result ofthe project—and genuine interest. “He felt a real

‘commitment to the idea,” says Nikki Roy, “and he was genuinely a sticking-the-neck-out type of guy.”

‘After that, finding the right ecosystem proved relatively straightforward, Save the Bay, an

environmental group in Rhode Island concerned with pollution in Narragansett Bay, had recently

‘complained to Massachusetts officials about toxic metals filtering into the bay from the Blackstone

River across the border in central Massachusetts, where there was @ heavy concentration of firms that

5. Acconting to Roy, EPA chose not to fund the project becuuse it “wasn't RCRA [Resource Conservation and

Recovery Act}fecused” and dil not have a large enough training component

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project 16-99-1197

did electroplating, metal finishing, and electronics manufacturing. “So,” Greenbaum explains, “we

‘were in part looking at how to beef up our efforts in that area.”

With the regional office and the specific site for DEP’s pilot lined up, DEM proceeded with its

application for its technical assistance program, which it called the Central Massachusetts Pollution

Prevention Project—of which DEP's Blackstone Project, as It was soon named, would be a subset. When

its grant award came through in December 1988, to the tune of $289,000, the agency passed on funds to

DEP to pay for one new siaff position in the pilot. Later, in the spring of 1989, DEP (as it was by then

officially known) added another position, funded by a grant from the National Governors Association ®

Accordingly, when Stanton was appointed assistant commissioner for waste prevention in March 1989, a

total of four new staff positions were funded (two by DEP itself) for the pilot project. But while the

location and the funds were settled, Stanton found that many other questions about the pilot remained.

‘Questions and Doubs

“Most of the questions and doubts about the project were to be found in DEP itself, and many of

them concemed the way the department had carried out its inspectional responsibilities, The

organization that DEP had built up over the years mirrored that of the Environmental Protection

‘Agency, which in tum reflected the accretion of federal environmental law in discrete categories of

pollution media—e.g, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Resource Conservation and

Recovery Act (governing the disposal of hazardous waste). The individval programs at DEP had

developed their own inspection styles and culture, driven in part by the technical and procedural

aspects of the work they performed, They were overseen by dlfferent paris of EPA, kept separate files

and, to an extent, visited separate parts of the facilities they inspected. Reporting formats likewise

varied. The media programs did not circulate their inspection reports among each other (though

inspectors would notify the appropriate program if they spotted a potential violation in another

‘medium during an inspection visit). "I sat literally adjacent to people in another program.” says

Michael Maher, the regional engineer” in charge of the Central Regional Office's Bureau of Waste

Prevention, who started his career as an ait quality inspector, “and knew very, very little about what

that program did.” There was, Maher adds, “a very strong allegiance to the program” among the field

inspectors and their immediate supervisors, the section chiefs, “ ., That's the program they grew to

like and become more expert in, and they wanted to stay focused on that program.”

Bullt into the idea of a multimedia inspection, however, was the assumption that inspectors in

‘one medium could be trained to conduct an inspection in other media. Most section chiefs questioned

‘whether such inspections would be thorough enough, arguing that—as their own careers attested—

‘years of training and on-the-job experience were needed to attain a suitable level of expertise, Tom

Cusson, air quality section chief in DEP's Central Regional Office, a 21-year veteran of that program,

5 ‘The NGA grant stipulated thatthe money would be vsed to pay for an inspector check for compliance with federal

and state toric use reporting laws,

7 Regional engineers had supervisory responsiblity for the burea

beaded up the individual programs within a bureau, reported (0

fergocizational chart of a regional burezu of wasle prevention.)

€16-98-1197.0

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project.

points to the lengthy learning period for neophytes in his area. “Generally when I'm bringing in

‘somebody new,” he says, “especially if they don’t know anything about air quality, we figure [they

‘need! a year before we're able to turn them loose to don inspection on their own.” Air quality

inspectors, he continues, had to master a range of technologies, from boilers to major power plants, as

‘well as the tangle of laws and regulations governing their medium. “Ihave two file drawers full of

laws,” Cusson points out, “just on air quality.”

‘As the managers most directly responsible for the daily conduct of inspections, section chiefs

felt concemed about signing off on reports done by an inspector from another program. It was in parta

matter of control, says Mike Maher. Section chiefs had “years and years of background,” he notes, and

were used to thinking, for example, that ““only air could do air [inspections] and now fin the pilot]

somebody else would be planning what the air inspections would be; maybe an air person wouldn't even

bbe going out on that inspection, but I'm still responsible as the air section chief for what happens at

that plant’ So if starts to build tension.”

‘Along with questions of expertise, there was the matter of how the different inspection and

enforcement routines that had grown up among the programs over the years would be reconciled. The

differences, stylistic and otherwise, could run deep. “We have been accused of being very picky,”

‘observes John Kronopolus, hazardous waste section chief in the Central Regional Office. “A lotof times

‘our regulations say, it [ue,, a violation] is there or not. Whereas ... potentially IWW [Industrial

Wastewater] has a discharge that may or may not violate a sewer use permit, or [there's] an air quality

issue that may or may not require enforcement. ... You know, 21c [the portion of state law regulating the

‘management of transportable hazardous waste] is picky, and air is not. There's a philosophical

difference. We cite everything [as a violation]. They pick and choose what they want to [enforce].” It

‘may be, Kronopolus speculates, that “the people who came to this group [hazardous waste] fee!

comfortable with saying, it’s black or white. And then other people are happy with gray.”

‘Cusson seconds the notion that inspectors were not necessarily fungible when it came to the

medium they worked in. “Some people choose to be lawyers,” he says, “some people choose to be

‘engineers, some people choose to be inspectors or analysts—because that's not only what they like to do,

but because that's what they do best. You can't just look at a title on a sheet of paper that says

‘environmental analyst’ [ie,, inspector] and therefore [assume] that person must be able to do

everything that has to do with the environment. That isn’t how it works.” Moreover, Cusson believed,

specialization was important in regulating complex environmental sysiems. “I like to use the analogy

of the medical profession,” he says. “You have general practitioners that you go to when you're sick.

‘They tell you, “You have heart disease, you need open heart surgery.’ Now, you're not going to lay down

‘ona table and say, ‘Okay, cut me open and do it’ You're going to go toa heart specialist. The

‘environmental area is pretty much the same kind of thing. You have a very strong need for specialists

in each of the different media.” What the DEP pilot was trying to do, he feared, “is take the

specialists and make them into generalists.”

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project 16-93-1197.

Interagency Relations

Concems about the Blackstone project were not limited to those who worked in DEP. In DEM’s

Office of Safe Waste Management, which would provide the technical assistance for the pilot, there

‘were worries about teaming up with an agency whose relations with industry were primarily

adversarial. The Safe Waste Management office was in the process of being, transformed from a small

‘group of about seven or eight employees to a stand-alone unit—called the Office of Technical

Assistance (OTA)—in the Environmental Affairs Secretariat that would eventually grow to employ

about30. OTA owed its new prominence to the Toxic Use Reduction Act (TURA), which was wending its

way through the state legislature and would be officially signed into law in July 1989. The new law

would, among other things, expand the number of firms currently required to report toxic substance use

‘under federal statutory provisions (usually referred to as SARA 313) and require “large quantity users”

to develop plans for reducing use of toxics in their industrial processes. TURA gave to OTA the task of

providing technical assistance to toxics users, stipulating that the “office shall not make available to

IDEP] information it obtains in the course of providing technical assistance,” unless the user agreed or @

‘threat to public health was involved.

{twas how to maintain this confidentiality that was of chief concem to OTA. The issue of

‘whether technical assistance personnel should report violations they observed had been “a major bane

‘of contention [with DEP] forever,” says Tim Greiner who worked in the Oifice of Safe Waste

Management and later in OTA. From the technical assistance viewpoint, he explains, “we had spent a

Jot of time building trust among firms who thought, ‘The only reason government comes to our plants is to

inspect us and fine us’ And we said, 'No, we're here to provide technical assistance, ... We do not report

anything to DEP unless what we see is an imminent threat to human health.’ There were fears that an.

alliance with DEP could undermine that understanding. “The culture at OTA, or at DEM at the time,”

Greiner continues, “was always that DEP could really muff it up if we interacted with them. They

‘could ruin the trust we built with industry.”

From DEP's standpoint, the problem was, in Daniel Greenbaum’s words, a "good guy-bad guy,

white hat-black hat syndrome.” DEP staff, he wrote in 1992, were “wary of their colleagues in ‘white

hats’ and the OTA staff unwilling to tum anyone, even significant violators they found, in to [DEPL.”®

It would sometimes happen, Greenbaum says, that DEP inspectors would show up at a site recently

visited by OTA and spot a serious violation. “And [the company representative] would say, ‘Oh, well,

somebody from the state was here and they didn't say anything about this.” While relations between

the two organizations had warmed in recent months, as the Idea for the project took shape, both sides

had questions about how to fashion a modus operandi that would suit their different missions and

strategies.

Another kind of modus operandi would also eventually have to be worked out with EPA,

Despite interest in source reduction at the policy level, the federal agency was still organized along

strict program lines and, at least at the regional level, not inclined to change. “Over a 20 years’ time

span,” says Stanton, “.. these independent environmental watchdog groups within EPA developed

8 Daniel Greenbaum, “The Massachusetts Potusion Prevention Initiative,” July 1992.

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project. C16.93-1197.0

relatively independently of each other. They tended to look at different things; they tended to like

their paperwork done differently.” And, as Daniel Greenbaum points out, they liked to count their

inspection “beans” separately; program grants from EPA were ted to the volume of inspections

conducted by specialists within a given program area. It was not clear how inspections under the

proposed pilot could meet EPA program requirements and still retain a whole-facility, multimedia

orientation.

Relations with Regulated Firms

Finally, there was the question of the impact of the pllot on regulated companies. DEP

anticipated some benefits to companies in the form of fewer inspections per year—a benefit most likely

to be approciated by firms that were classified as “major sources” in more than one medium, and

therefore subject to more than one inspection per year. Greenbaum also expected companies would have

fewer contradictory requirements to deal with, and fewer regulators to track down. He had heard

‘complaints from businesses that “I can never get the answer from DEP, itjust takes forever. And one guy

‘came in here and told me to do this, and another one came in here and told me to do that.”” Smaller

firms, on the other hand, were expected to benefit from increased exposure to OTA, to whom DEP.

inspectors would refer them for help in source reduction approaches to compliance,

[At the same time, however, there were questions about how the largest companies would cope

‘witha team of inspectors descending on them to conduct a one-stop inspection. Greenbaum recalls

asking, “We're going to send all four inspectors under this [pilot] to the same plant on the same day??

Isn't that going to scare the bejesus out of them? Aren't they going to go crazy?” Some lange companies,

such as Wyman-Gordon, a firm that made aerospace parts and employed over 2500 people in 1989, had

set up their environmental engineering departments to correspond to DEP's program organization, so

that individual engineers were assigned to a specific medium. The company’s engineers, says one,

understood the regulations “probably on a par” with DEP's own inspectors. When a program inspector

from DEP visited Wyman-Gordon, the corresponding company specialist would accompany him or her

con the inspection. Over time, a sense of continulty and rapport developed, says one Wyman-Gordon

engineer; the inspector grew familiar with the plant and “knew where to look” during the two to four

hours it took to tour the facility. Multimedia inspections would inevitably rearrange those

relationships and the divisions of labor that had grown up around them.

Stanton’s Task

‘The job of designing an operational plan that would determine how all of these internal and

extemal relations would be arranged for the life of the pilot project, and perhaps beyond, fell to the

‘new assistant commissioner for waste prevention. Patricia Deese Stanton had come to her new position

(having beaten out Central Regional Office Director Barry Fogel for the job) after two-and-a-half

{years as director of the DEP”s Division of Water Supply: previously, she had worked as a project

9 Taree of the inspectors would come from the water, sir quality, and hazardous waste programs: the fourth would

inspect for compliance with federal and stale toxie use reporting laws (SARA 313 and TURA),

10

Preventing Pollution in Massachusetts: The Blackstone Project________16-99-1197.0

manager at the consulting firm of Arthur D. Little—experience that would serve her well in dealing

‘with the still inchoate Blackstone project. In the newly reorganized agency, Stanton was the official in

DEP headquarters with direct responsibility for the air quality, industrial wastewater, and hazardous

waste programs, She would, however, be operating from a position of some weakness in relation to the

Central Regional Cifice: she did not have direct line authority over the regional offices and

inspectors.

un

DEQE

DEP

DEM

Office of Safe Waste

Management

OTA

Glossary of Agencics

Department of Environmental Quality Engineering, original

ame of sate environmental regulatory agency

Department of Environmental Protection, new name given to

DEQE after departmental reorganization

Department of Environmental Management, a sister agency

of DEP in the state Executive Office of Environmental Affairs,

charged with management of state parks, forests, recreational

facilities, and watersheds

‘Unit within DEM that offered free technical assistance in

source reduction techniques

Office of Technical Assistance, former Office of Safe Waste

‘Management, now removed from DEM and made a free-

standing unit within Executive Office of Environmental Affairs

2

Deparment of Environmental Protection

‘Organization Chart

Depuiy

[Commissioner

Adminstration

13.

Source: Daniel S. Greenbaum, “The Massachusetts Pollution Prevention Initiative,” July 1992.

Exhibit 2

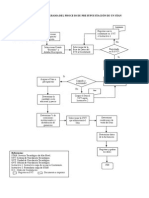

Organizational Chart: Regional Bureau of Waste Prevention

Commissioner

fae

creeeeaead aa

cmemmuion| | eter

Operations, ‘Development

a a

feet

saeaeen com

Regional Engineer

Waste Prevention

Section Chiefs:

Air Quality Control

Hazardous Waste Management|

Industrial Wastewater

Solid Waste Management

Source: Department of Environmental Protection

Appendix A

Background Note on the Department of Environmental Protection.

Until late in 1988, DEP was known as the Department of Environmental Quality Engineering

(DEQE). Established in 1975, DEQE was one of four departments under the umbrella of the state

Executive Office of Environmental Affairs. In broad terms, the department was given responsibility for

“ensuring clean air and water, the safe management and disposal of solid and hazardous wastes, the

timely cleanup of hazardous waste sites and spills, and the preservation of wetlands and coastal

resources."! Some 13,000 facilities in Massachusetts—everything from factories to wastewater

treatment plants to gas stations to landfills—fell under the DEQE’s regulatory purview. Each yeat,

‘among other tasks, the department issued over 4,000 environmental permits and licenses? and conducted

roughly the same number of or-site inspections of facilites that discharged wastewater, emitted air

pollution, or generated hazardous waste. To carry out its responsibilities, DEQE had an operating

budget of about $45 million and roughly 1,000 employees—many of them with backgrounds in civil,

environmental, or chemical engineering—who worked either at headquarters in Boston or in one of its

four regional offices.

‘The mandate and much of the direction for DEQE’s duties came from an imposing mass of

fecleral and state law, amended many times over as environmental issues in the US grew more

prominent, and increasingly complicated. At the top of the environmental regulatory pyramid stood

the EPA, which funded about 25 percent of DEQE’s budget? The EPA delegated much of its authority

under federal law to states that met its standards and regulations; its program grants—eg,, in alr

pollution, water pollution, hazardous waste—typically stipulated what kind of permitting,

inspection, and enforcement activities the delegatee was expected to do, sometimes even specifying

which facilities were to be inspected.

1 Finding Your Way Through DEP, November 1992.

2 Among other things. the department issued permits for new facilities or modifications of existing ones that were

fxpacied to bave en impact oa the envizonment; program engingers reviewed facility plane as part of the

Permitting process.

3 Tu budgetary impact on some todividval programs was much higher. About $$ percent of the air quality program,

for example, was federally funded,

5

Internal Organization. At DEQE headquarters, the deputy commissioner for policy and.

Program development oversaw nine divisions, most of which paralleled EPA programs and the

congressional mandates that had called them into being, Out in the four regional offices, a

corresponding structure of programs, organized by medium and headed by section chiefs, carried out

‘work of inspecting facilities, taking appropriate enforcement actions, and reviewing plans and issuing

permits. After the 1988 reorganization, in which DEQE became DEP, the programs were grouped into

three bureaus, each headed by an assistant commissioner in the central office and a regional engineer in

the regional offices.

Tt was the section chiefs—most of whom were drawn from the ranks of inspectors and engineers

in thelr respective programs—who assigned the inspectors’ work and reviewed their post-inspection

reports. The inspections aimed to ensure compliance with state and federal environmental laws and,

where applicable, the requirements of state licenses and permits. Basically, they were the task of

three progrems—air quality, hazardous waste, and industrial wastewater, which inspected facilities

that discharged to groundwater and surface water; a fourth unit, the Rightto-Know Office, checked

for compliance with federal and state reporting laws for “large quantity toxic users.” Typically,

inspectors visited a “major source” of pollution in their medium once a year—usually in accordance with

EPA guidelines—and a “minor source” ona less frequent basis. After conducting theit inspections, DEP

inspectors wrote up reports of their findings and, where necessary, started enforcement procedures,

‘These latter ranged from notices of noncompliance, which one DEP official characterizes as “a slap on

the hand,” to administrative orders and penalty assessments, which were appealable, to consent

orders, which were not. After review by the appropriate section chief, reports and enforcement notices

‘were then signed by one of the office’s regional engineers.

16

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Gaceta Innovacion 05Document16 pagesGaceta Innovacion 05Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0213911119301591 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S0213911119301591 MainFRANCISCA INDIRA CABRERA ARAYANo ratings yet

- Gaceta Innovación Suplemento Especial No 1 Diciembre 2015Document14 pagesGaceta Innovación Suplemento Especial No 1 Diciembre 2015Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Panel EsDocument2 pagesPanel EsLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Gaceta Innovacion 06Document16 pagesGaceta Innovacion 06Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Plan de Desarrollo Institucional Vision 2030 ANUIESDocument68 pagesPlan de Desarrollo Institucional Vision 2030 ANUIESLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Calendario 2014Document1 pageCalendario 2014Gzuz IRNo ratings yet

- Gaceta Abrazando La Innovación No 3 Abril 2015Document13 pagesGaceta Abrazando La Innovación No 3 Abril 2015Felipe Valencia RiveraNo ratings yet

- Gaceta Abrazando La Innovación No 4 Julio 2015Document13 pagesGaceta Abrazando La Innovación No 4 Julio 2015Felipe Valencia RiveraNo ratings yet

- Gaceta Innovacion 01Document12 pagesGaceta Innovacion 01Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Gaceta Innovacion 02Document15 pagesGaceta Innovacion 02Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Toda Mujer Debe Hacerse Una Sesión Fotográfica Por Lo Menos Una Vez en Su VidaDocument1 pageToda Mujer Debe Hacerse Una Sesión Fotográfica Por Lo Menos Una Vez en Su VidaLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Gaceta Abrazando La Innovación No 4 Julio 2015Document13 pagesGaceta Abrazando La Innovación No 4 Julio 2015Felipe Valencia RiveraNo ratings yet

- Gaceta Innovación Suplemento Especial No 1 Diciembre 2015Document14 pagesGaceta Innovación Suplemento Especial No 1 Diciembre 2015Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Pres ERivera 2Document38 pagesPres ERivera 2Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- 930f41 1a1ce99Document8 pages930f41 1a1ce99Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Proceso de Compra TIC X Tipo de RecursoDocument1 pageProceso de Compra TIC X Tipo de RecursoLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Objetivos, Una Aproximación A Su ConstrucciónDocument10 pagesObjetivos, Una Aproximación A Su ConstrucciónLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Lineamientos Costo BeneficioDocument14 pagesLineamientos Costo BeneficioLorenaMoreiraNo ratings yet

- 1197 0Document16 pages1197 0Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Flujograma Emision de Orden de FacturacionDocument1 pageFlujograma Emision de Orden de FacturacionLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Flujograma Emision de Orden de FacturacionDocument1 pageFlujograma Emision de Orden de FacturacionLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Objetivo General y Objetivos EspecíficosDocument4 pagesObjetivo General y Objetivos EspecíficosSociocultural Project90% (156)

- 1197 0Document16 pages1197 0Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Elementos Conceptuales y Aplicaciones de Microeconomía para La Evaluación de ProyectosDocument58 pagesElementos Conceptuales y Aplicaciones de Microeconomía para La Evaluación de ProyectosLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Propuesta de Trabajo en Materia de Planeación Participativa y Generación de Un Plan Municipal de DesarrolloDocument1 pagePropuesta de Trabajo en Materia de Planeación Participativa y Generación de Un Plan Municipal de DesarrolloLuis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- ICSV1Document64 pagesICSV1Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- Manual 58Document111 pagesManual 58Ernesto CosmeNo ratings yet

- Anexo Metodologico Indice de Competencia Electoral-1Document4 pagesAnexo Metodologico Indice de Competencia Electoral-1Luis Gómez CastroNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)