Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Free Movement of Workers

Uploaded by

MehreenCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Free Movement of Workers

Uploaded by

MehreenCopyright:

Available Formats

1

FREE MOVEMENT OF

WORKERS

ARTICLE 45 OF THE TFEU guarantees the right of free movement of workers:

Such freedom of movement shall entail the abolition of any discrimination

based on nationality between workers of the Member States as regards

employment, remuneration and other conditions of work and employment

Definition of a Worker

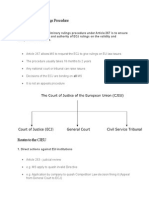

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has now and then insisted that the definition of

a worker is a matter of EU law rather than National law.

In HOEKSTRA, the ECJ position on workers is that:

any person who pursues employment activities which are effective and

genuine to the exclusion of activities on such a small scale as to be

regarded as purely marginal and ancillary is treated as a worker

The ECJ in LAWRIE-BLUM held that:

the essential feature of an employment relationship, however, is that

for a certain period of time a person performs services for and under

the direction of another person in return for which he receives

remuneration

For an economic activity to qualify as employment under ARTICLE 45, rather than

self-employment under ARTICLE 49 OF THE TFEU, there must be a relationship of

subordination. There is however, no single EU concept of a worker and it varies

according to the context it arises under EU law.

The practice must merely constitute as an economic activity as seen in Bosman.

Moreover, the irregular nature of remuneration is considered irrelevant as in R v

Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

The concept of remuneration was and hence of economic activity was pushed a bit

further in Steymann. It was considered that the fact, the work might be seen in

conventional terms as being unpaid did not mean that it was not effective economic

activity. Remuneration in kind is also acceptable.

Moreover, Article 45 would apply even where the work was done outside the

Community, so long as the legal relationship of employment was entered within the

Community: WALRAVE AND KOCH.

The ECJ further extended this ruling in BOUKHALFA, that the Article applied also to the

employment of a Member State national which was entered into and primarily

performed in a non-member country in which the national resided.

Article 45 are not only of vertical direct effect as in WALGRAVE AND KOCH and BOSMAN,

but are also horizontally applicable to the actions of individuals who do not have the

power to make rules regulating gainful employment as per ANGONESE CASE.

The wide interpretation shows that it is a fundamental freedom with great relevance

Part-Time Workers

All workers in the Member States have the right to pursue the activity of their

choice within the Community, irrespective of whether they are permanent, seasonal

or frontier workers or workers who pursue their activities for the purpose of

providing services.

Even part time employment also falls within the scope of workers who are seeking

to supplement his earnings below the subsistence level as per LEVIN and KEMPF.

However, their activities must satisfy the requirements in HOEKSTRA.

Purpose of Employment

The purpose for which the employment is undertaken is not relevant in determining

whether a person is a worker. All that is required is that the employment is genuine

and not marginal so as to benefit from ARTICLE 45. However, there are cases in which

some account has been taken of the purpose of the employment. This concept is

exemplified in BETTRAY.

The crucial factor is whether the work is capable of being regarded as forming part

of the normal labour market: TROJANI V CPAS.

An EU national who undertakes work for a temporary period purely as a means to

qualify for an educational course will not be entitled to all the same advantages as a

fully-fledged worker under EU law as per the ECJ in BROWN.

The ECJ reiterated the importance of objective factors such as hours of worked and

remuneration over other subjective factors such as motive and conduct in NINNIORASCHI.

Job Seekers

A job seeker also falls within the definition of a worker as per the ECJ in ANTONISSEN.

Member States retain the power to expel a job-seeker who does not have prospects

of finding work after a reasonable period of time. This concept was followed in

COMMISSION V BELGIUM and LEBON.

Article 45 of the TFEU: Discrimination

ARTICLE 18 OF THE TFEU, which contains the general prohibition on grounds of

nationality will be caught by ARTICLE 45.

Direct Discrimination

It entails different treatment both in law and in fact of foreigners in a Member State.

A good illustration of direct discrimination is seen in REYNERS CASE.

In COMMISSION V FRENCH REPUBLIC, the ECJ ruled that ARTICLE 45 was directly

applicable in the legal system of every Member State, and would render all

contrary national law inapplicable. Further, a state can be held in breach of ARTICLE

45, where the discrimination is practiced by any public body as in COMMISSION V ITALY.

Indirect Discrimination

Indirect Discrimination entails equal treatment in law but different treatment in fact

i.e. in practice, a rule or criteria that is neutral at first sight, but which

nevertheless has a detrimental effect or a detrimental impact primarily on

foreigners as seen in ALLURE AND COONAN.

ARTICLE 45 prohibits any condition of eligibility for a benefit which is more easily

satisfied by national than by a non-national worker.

The ECJ has relaxed the requirements for proof of indirect discrimination in OFLYNN.

In order for indirect discrimination to be established it was not necessary to prove

that a national measure in practice affected a higher proportion of foreign workers,

but merely that the measure was intrinsically liable to affect migrant workers more

than nationals.

Indirect Discrimination also includes benefits that are made conditional, in law or

fact, on residence, place of origin requirements, or place of education requirements

that can more easily be satisfied by nationals that non-nationals: UGLIOLA. This was

clearly illustrated in COMMISSION V BELGIUM.

A further form of indirect discrimination is the imposition of a language requirement

for certain posts, since it is likely that a far higher proportion of non-nationals than

nationals will be affected by it: COMMISSION V GREECE.

However, since such a requirement may well be legitimate, ARTICLE 3(1) OF

REGULATION 1612/68, allows for the imposition of conditions relating to linguistic

knowledge required by reason of the nature of the post to be filled.: GROENER.

Another form of indirect discrimination is the imposition of a double-burden regulatory

requirement, which does not recognize appropriate qualifications or certification already

received in the home state: COMMISSION V PORTUGAL .

Non-Discriminatory Measures

The ECJ has ruled that even non-discriminatory restrictions may breach the Treaty if

they constitute an excessive obstacle to freedom of movement: BOSMAN CASE.

A good illustration of the application of ARTICLE 45 to such restrictions can be seen in

COMMISSION V DENMARK and VAN LENT.

Neutral national rules could be regarded as material barriers to market access only

if it were established that they had actual effects on market actors similar to

exclusion from the market: GRAF.

Internal Situations

ARTICLE 45, does not prohibit discrimination in a so-called wholly internal situation.

This has the effect that national workers cannot claim rights in their own Member

State, which workers who are nationals of other Member States could claim there as

seen in SAUNDERS.

A worker will be able to use ARTICLE 45 against his or her own state where they are

discriminated against after returning to work in their own State having been

previously and resided in another Member State before: DE GROOT.

Article 45 of the TFEU: Justifications

Article 45(3) and (4) of the TFEU contain the Treaty justifications. These are further

supplemented by Directive 2004/38.

Article 45(3)

It contains exceptions to discriminatory provisions on grounds of public policy, public

security and public health Tsakouridis Case

Objective Justification

Justifications for indirect discrimination are broad, and not confined to the exception

set out in the Treaty or secondary legislation as seen in SCHUMACKER.

The ECJ close scrutinizes claims that attempt to justify the restrictions as evidenced

in TERHOEVE.

Article 45(4): The Public Service Exception

The ECJ has taken an expansive approach to the definition of a worker. Conversely,

its approach to the limiting clause in ARTICLE 45(4) has been restrictive.

The ECJ in COMMISSION V BELGIUM held that the aim of the Treaty provisions was to

permit Member States to reserve for nationals those posts, which would require a

specific bond of allegiance and mutuality of rights and duties between state and

employee. This statement proves to be two-fold:

1. they must involve participation in the exercise of power conferred by public

laws; and

2. they must entail duties designed to safeguard the general interests of the

State.

Both the requirements are cumulative rather than alternative. A post will benefit

from the derogation in ARTICLE 45(4) only if it involves both the exercise of power

conferred by public law and the safeguarding of the general interests of the state:

LAWRIE-BLUM

However, Community law does not prohibit a Member State from reserving for its

own nationals those posts within a career bracket which involve participation in the

exercise of powers conferred by public law or the safeguarding of the general

interests of the state.

SOTGIU CASE makes it clear that ARTICLE 45(4) cannot be used to justify discriminatory

conditions for employment within the public service.

Scope of Protection of Workers

ARTICLE 46 OF THE TFEU provides for the European Parliament and the Council to

adopt secondary legislation to bring about the freedoms set out in ARTICLE 45.

Regulation 492/11:

Substantive Rights of Workers

ARTICLE 45 confers positive substantive rights of freedom of movement and equality

of treatment on EU workers. These rights are to some extent fleshed out by

secondary legislation and in particular by REGULATION 492/11 (previously REGULATION

1612/68) which has been amended by DIRECTIVE 2004/38.

Social and Tax Advantages

Article 7(2) of Regulation 492/11 confers social and tax advantages on workers. The

ECJ read ARTICLE 7(2) in MICHEL S in a strict manner i.e. it only concerned benefits

connected with employment.

However, the ECJ has since then departed from this restrictive interpretation and

presented an expansive approach in CRITINI V SNCF that ARTICLE 7(2) be read as to

include all social and tax advantages whether or not attached to the contract of

employment.

It applied not just to workers but also to surviving family members of deceased

worker and that although ARTICLE 7 refers only to advantages for workers, it covers

any advantage to a family member, which provides an indirect advantage to the

worker: INZIRILLO. This was further applied in REINA.

EVEN limited the rights under ARTICLE 7(2) which a worker may claim. The ECJ ruled

that the advantages which this regulation extends to workers who are nationals of

other Member States are all those which, whether or not linked to the contract of

employment, are generally granted to national workers primarily because of their

objective status as workers. An illustration of this limitation can be seen in DE VOS

and UGLIOLA.

Educational Rights for Workers

Article 7(3) provides that EU workers shall:

by virtue of the same right and under the same conditions as national

workers, have access to training in vocational schools and retraining

centres

The Article has been held to confer equal rights of access for non-nationals workers

to all the advantages, grants and facilities available to nationals.

This provision was interpreted restrictively in LAIR, excluding universities from the

scope of vocational institutions. However, the ECJ in MEEUSEN held that workers

could invoke the social advantages provision of ARTICLE 7(2) to claim entitlement to

any advantage available to improve their professional qualifications and social

advancement, such as a maintenance grant in an educational institution not

covered by ARTICLE 7(3).

However, in LAIR it was held that this interpretation is subject to the requirement

that there must be a link between the previous work and the studies in question.

This was reiterated in BROWN with the addition that the employment must not be

ancillary to the main purpose of pursuing a course of study.

The one exception that is permitted can be found under ARTICLE 7(3)(D) OF DIRECTIVE

2004/38, where a worker involuntarily unemployed was obliged by conditions on the

job market to undertake occupational retraining in another field of activity. Moreover,

under ARTICLE 35 OF DIRECTIVE 2004/38, Member States may refuse or withdraw rights

under the Directive in the case of abuse of rights or fraud.

Educational Rights for Children

ARTICLE 12, provides that:

the children of a national of a Member State, who is or has been

employed in the territory of another Member State, shall be admitted

to courses of general education, apprenticeship and vocational training

under the same conditions as the nationals of that State, if those

children reside in its territory.

This article was interpreted broadly by the ECJ in MICHEL S so as to benefit for

disabled nationals was included within ARTICLE 12 as access to education for children

of workers. This expansive reading was continued in CASAGRANDE to apply ARTICLE 12

in respect to any general measure intended to facilitate educational attendance.

Thus, ARTICLE 12 places the children of EU workers residing in a Member State in the

same position as the children of nationals of that state so far as education is

concerned.

The ECJ took a step further in broadening the scope of this article in GAAL by

conferring educational rights on children who were over 21 and non-dependent. And

then again in MORITZ, covering the childs right to educational assistance even

where the working parents have returned to their state of nationality.

Rights of Families of the Workers

Only workers and their immediate family covered by DIRECTIVE 2004/38, may avail

the social advantages found under ARTICLE 7 OF REGULATION 492/11.

This is evidenced by the ECJs Judgements in various cases: LEBON; REED; DIATTA;

SINGH; and BAUMBAST.

Directive 2004/38: Procedural Requirements

This Directive concerns the movement and residence of EU citizens and their

families, with family members defined in ARTICLES 2 AND 3 thereof.

The ECJ does not interpret the DIRECTIVE 2004/38 strictly as it aims to strengthen the

primary and individual right to move and reside freely within the Member States

that is conferred directly on Union citizens by the Treaty.

ARTICLE 6: allows all EU citizens and their families right of entry and residence for up

to three months without any conditions other than presentation of an ID card or

passport. It also recognises the temporary status of job-seeker.

ARTICLE 8: provides that workers and their families may be required to register with

the host state authorities, and upon presentation of a valid passport or ID card and

confirmation of employment (and, in the case of family members a document

attesting to the existence of the relevant family relationship, dependency) to

receive a certificate of registration as evidence of their underlying right of

residence.

ARTICLES 9 AND 10: family members who are not EU nationals are to be issued with a

residence card.

ARTICLE 4: requires Member States to grant citizens and their families the right to

leave their territory to go and work in other Member States simply on producing an

identity card or passport of at least five years validity. No visa requirement may be

imposed.

ARTICLE 5: sets down conditions for the right to enter another Member State i.e. all

that is required is a valid identity card or passport and a visa requirement is

impermissible, except for certain third country nationals. However, the visa must be

issued as soon as possible and free of charge as per ARTICLE 5(2).

The rights to reside and to work are not conditional upon initial satisfaction of the

formalities for which the Directive provides. The penalties imposed must be

proportionate and non-discriminatory. Penalties such as deportation, refusal of entry

or revocation of the right of residence constitutes as disproportionate for a failure to

fulfill administrative formalities.

Where the EU national or the family member does not have the requisite documents

or visas, the Member State shall give them every reasonable opportunity to obtain

the documents, to have them brought to them, or to prove their right of residence

by other means as per MRAX V BELGIUM.

The ECJ in METOCK clarified that the DIRECTIVE 2004/38S application is not conditional

on the family member of a Union citizen having previously resided in a Member

State.

The directive furthermore provides for nationals of non-member countries who are

family members of a Union citizen.

Job-Seekers and the Unemployed

ARTICLE 7(3): EU citizens who have ceased working, shall nevertheless retain the

status of worker where they are temporarily unable to work as a result of an illness

or accident; or where they are involuntarily unemployed after having been

employed for more than one year and having registered with the employment office

as job seekers.

In case of involuntary unemployment where a worker has embarked on a vocational

training may retain the status of a worker, but in cases where the worker has

voluntarily given up employment retention of this status is conditional upon the

training being related to the previous employment: RAULIN

Job-seekers do not enjoy the status of a worker in the full sense of the term,

although they enjoy a right of residence during the period they are seeking work,

and access to certain benefits which are specifically intended to facilitate access to

employment: COLLINS.

The ECJ is flexible in establishing the length of this period as in ANTONISSEN.

However, the right to remain in search of work must continue even after that period

so long as the person concerned provides evidence that he is continuing to seek

employment and that he has genuine chances of being engaged.

The Right of Permanent Residence

DIRECTIVE 2004/38 introduces the right of permanent residence for EU citizens and

their families, including non-nationals, who have resided lawfully for a continuous

period of five years in the host state.

ARTICLES 16-18: lays down the conditions under which EU citizens, including workers

and their families, may enjoy this right. ARTICLE 16(4), provides that the right of

permanent residence may be lost only through absences of more than two

consecutive years.

10

ARTICLES 19-21:

regulates administrative formalities. A document certifying

permanent residence is to be issued as soon as possible to EU nationals who have

verified their duration of residence. Non-EU national family members who enjoy a

derivative right of permanent residence are to be given a permanent residence

card, which is to be automatically renewed after every ten years and the validity

will be not be affected by the absence of less than two consecutive years.

ARTICLES 22-26: govern conditions under which the right of residence, including the

right of permanent residence, is to be enjoyed. It is to cover the whole of the

territory, and includes the right of equal treatment with nationals of the host state

within the scope of the Treaty, subject to such exceptions as are provided for by the

Treaty or in secondary legislation.

Directive 2004/38: Public Policy, Security and Health

Restrictions

ARTICLES 2733 OF DIRECTIVE 2004/38 govern the restrictions on the right of entry

and residence, which Member States may impose on grounds of public policy,

security or health. An innovation of DIRECTIVE 2004/38 has been the introduction of

three levels of protection against expulsion on these grounds:

1. A general level of protection for all individuals covered by EU law

2. An enhanced level of protection for individuals who have already gained the

right of permanent residence on the territory of a Member State

3. A super enhanced level of protection for minors or those who have resided for

10 years in a host state.

There is a significant body of case law concerning the circumstances in which Member

States may expel EU nationals or their family members on public policy or security

grounds as exemplified in the following cases: VAN DUYN; ADOUI AND CORNUAILLE; and

RUTILI.

The substantive and procedural protection for individuals subject to an expulsion

order are now set out in ARTICLE 28 OF DIRECTIVE 2004/38.

ARTICLE 28(1): requires that before making an expulsion order the Member State

must take into consideration the period for which the individual has stayed the host

Member State, his age, state of health, family and economic situation, social and

cultural integration and the extent to his links with the country of origin.

ARTICLE 28(2): provides enhanced level of protection to EU citizens, stating that they

may only be expelled for serious grounds of public policy or public security.

11

ARTICLE 28(3): provides for an even more stringent level of protection for a minor or

an EU citizen residing in the host State for more than ten years stipulating that they

can only be expelled on imperatives grounds of public security.

LAND BADEN CASE holds that the ECJs interpretation of ARTICLES 27 AND 28 OF THE

DIRECTIVE and the conditions must be satisfied for an expulsion to be lawful.

ARTICLE 29(1): governs the public health requirement by specifying that only

diseases with epidemic potential as defined by the relevant instruments of WTO,

and other infectious or contagious parasitic diseases subject to protection in the

host Member State will justify measures restricted freedom of movement.

ARTICLE 29(2): sets out a three-month period following arrival after which diseases

occurring cannot constitute grounds for expulsion.

ARTICLE 29(3): where there are serious indications that it is necessary Member States

may within three-months of the date of arrival, require persons entitled with a right

of residence to undergo a medical examination free of charge to certify that they

are not suffering from any disease.

ARTICLE 30: requires that the persons concerned must be notified of the decision in

such a way that they can comprehend its content and implications: ADOUI and

CORNUAILLE

ARTICLE 31: gives EU citizens the right for judicial review or appeal against the

adverse decision taken by Member States.

ARTICLE 32: provides that where someone has been validly excluded on public policy

or security grounds they may apply to have the exclusion order lifted after a

reasonable period, and no later than three years from the enforcement of the final

exclusion order, by arguing that there has been a material change in the

circumstances justifying their exclusion. States must decide on such application for

re-admission within six months, but the applicants have no right of entry to the

territory while the application is being considered.

You might also like

- EU Law Problem Question - Direct Effect, Indirect Effect and Incidental Horizontal EffectDocument13 pagesEU Law Problem Question - Direct Effect, Indirect Effect and Incidental Horizontal EffectPhilip Reynor Jr.60% (5)

- Preliminary References to the Court of Justice of the European Union and Effective Judicial ProtectionFrom EverandPreliminary References to the Court of Justice of the European Union and Effective Judicial ProtectionNo ratings yet

- Topic 10 - Free Movement of People - Workers - Seminar SummaryDocument19 pagesTopic 10 - Free Movement of People - Workers - Seminar SummaryTharani KunasekaranNo ratings yet

- CitizenshipDocument32 pagesCitizenshipAnushi AminNo ratings yet

- Examiners' Report 2014: LA3024 EU Law - Zone BDocument8 pagesExaminers' Report 2014: LA3024 EU Law - Zone BJUNAID FAIZANNo ratings yet

- The European Union Has Irrevocably Strayed Away From Its Initial Economic Goals and Is Now Mostly About People and Their RightsDocument2 pagesThe European Union Has Irrevocably Strayed Away From Its Initial Economic Goals and Is Now Mostly About People and Their RightsuzeeNo ratings yet

- Supremacy of EU LawDocument6 pagesSupremacy of EU LawMehreen100% (1)

- Chalmers Et Al Ch.18 Free Movement MEQRDocument39 pagesChalmers Et Al Ch.18 Free Movement MEQRSimran BaggaNo ratings yet

- Examiners' Reports 2017: LA2024 EU Law - Zone BDocument11 pagesExaminers' Reports 2017: LA2024 EU Law - Zone BFahmida M RahmanNo ratings yet

- Supremacy of EU Law revisitedDocument16 pagesSupremacy of EU Law revisitedXsavier870% (1)

- Fairhurst Law of The European Union PDFDocument2 pagesFairhurst Law of The European Union PDFElvinNo ratings yet

- Supremacy of EU LawDocument6 pagesSupremacy of EU LawMehreen100% (1)

- "Illegal Number Games" Is Any Form of Illegal Gambling Activity Which UsesDocument4 pages"Illegal Number Games" Is Any Form of Illegal Gambling Activity Which Usesmaria luzNo ratings yet

- General Studies Gaurav Agarwal IASDocument455 pagesGeneral Studies Gaurav Agarwal IASPraveen Ks80% (5)

- CHapter 6 - Free Movement of ServicesDocument10 pagesCHapter 6 - Free Movement of ServicesMehreenNo ratings yet

- Fmop (Revision Notes)Document11 pagesFmop (Revision Notes)Julien Tuyau100% (1)

- Summary Free Movement (-Last 10 Pages)Document8 pagesSummary Free Movement (-Last 10 Pages)Rutger Metsch100% (2)

- The Principle of Free Movement of Workers Within The EUDocument7 pagesThe Principle of Free Movement of Workers Within The EUSilvia DchNo ratings yet

- Direct EffectDocument5 pagesDirect Effecttasmia1100% (2)

- Direct Effect EssayDocument4 pagesDirect Effect Essayvictoria ilavenilNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of WorkersDocument12 pagesFree Movement of WorkersMaxin MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Cases ExamDocument10 pagesCases ExamRutger MetschNo ratings yet

- EU Law - Course 15 - Free Movement of GoodsDocument7 pagesEU Law - Course 15 - Free Movement of GoodsElena Raluca RadulescuNo ratings yet

- UK measures to curb smoking, drinking and obesity face ECJ scrutinyDocument5 pagesUK measures to curb smoking, drinking and obesity face ECJ scrutinyMatteo Esq-CrrNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Pillars of EU LawDocument10 pagesConstitutional Pillars of EU LawGandhi PalanisamyNo ratings yet

- Implications of European Union's Accession To The European Convention On Human RightsDocument8 pagesImplications of European Union's Accession To The European Convention On Human RightsJana LozanoskaNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of Goods IIDocument12 pagesFree Movement of Goods IIsaqib shahNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of GoodsDocument3 pagesFree Movement of GoodsgoerdogoNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of GoodsDocument1 pageFree Movement of Goodssiegfried_92No ratings yet

- Direct and Indirect Effect EU LawDocument2 pagesDirect and Indirect Effect EU LawThomas Edwards100% (1)

- Free Movement Rights of EU and Non-EU CitizensDocument6 pagesFree Movement Rights of EU and Non-EU CitizensDajana GrgicNo ratings yet

- Enforcement Direct Effect Indirect Effect and State Liability in DamagesDocument47 pagesEnforcement Direct Effect Indirect Effect and State Liability in Damagesyadav007ajitNo ratings yet

- The Principle of State LiabilityDocument2 pagesThe Principle of State LiabilitygayathiremathibalanNo ratings yet

- Eu LawDocument7 pagesEu Lawh1kiddNo ratings yet

- General Principles of European LawDocument12 pagesGeneral Principles of European LawJohn DonnellyNo ratings yet

- Vertical AgreementsDocument5 pagesVertical AgreementsAmanda Penelope WallNo ratings yet

- The Direct Effect of European Law: PrecedenceDocument2 pagesThe Direct Effect of European Law: PrecedenceSilvia DchNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of GoodsDocument14 pagesFree Movement of GoodsMehreen100% (1)

- Human Rights in The EU (10469)Document21 pagesHuman Rights in The EU (10469)MehreenNo ratings yet

- Case Law List EU LawDocument17 pagesCase Law List EU Lawikbenlina_63No ratings yet

- Direct Effect + SupremacyDocument10 pagesDirect Effect + Supremacynayab tNo ratings yet

- State Liability in EUDocument10 pagesState Liability in EUGo HarNo ratings yet

- University of London La2024 OctoberDocument3 pagesUniversity of London La2024 OctoberSaydul ImranNo ratings yet

- The Free Movement of Persons - EU LawDocument7 pagesThe Free Movement of Persons - EU LawJames Robert KrosNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of Goods - CBDocument26 pagesFree Movement of Goods - CBCristinaBratu100% (3)

- Introduction of The Project: Why Did The Crisis Affect Greece, The Most?Document44 pagesIntroduction of The Project: Why Did The Crisis Affect Greece, The Most?Srishti BodanaNo ratings yet

- Substance and ProcedureDocument3 pagesSubstance and ProcedureHemant VermaNo ratings yet

- Position Paper - Estonia On Child Soldiers and ConflictDocument4 pagesPosition Paper - Estonia On Child Soldiers and ConflictNikhil HiraniNo ratings yet

- The Preliminary Rulings ProcedureDocument9 pagesThe Preliminary Rulings ProceduregayathiremathibalanNo ratings yet

- Rights of Non-EU Nationals Married to EU CitizensDocument17 pagesRights of Non-EU Nationals Married to EU CitizensSumukhan LoganathanNo ratings yet

- Brasserie Du Pêcheur v. Germany, Joined Cases C-46/93 and C-48/93Document2 pagesBrasserie Du Pêcheur v. Germany, Joined Cases C-46/93 and C-48/93Simran BaggaNo ratings yet

- Only The Workers Can Free The Workers: The Origin of The Workers' Control Tradition and The Trade Union Advisory Coordinating Committee (TUACC), 1970-1979.Document284 pagesOnly The Workers Can Free The Workers: The Origin of The Workers' Control Tradition and The Trade Union Advisory Coordinating Committee (TUACC), 1970-1979.TigersEye99100% (1)

- The Role of The Security Council in The Use of Force Against The Islamic State' (2016)Document35 pagesThe Role of The Security Council in The Use of Force Against The Islamic State' (2016)Antonio HenriqueNo ratings yet

- EU Law Exam Notes PDFDocument51 pagesEU Law Exam Notes PDFstraNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of Goods (EU), Direct Effect and SupremacyDocument25 pagesFree Movement of Goods (EU), Direct Effect and SupremacyThelma ParkerNo ratings yet

- Examiners' Report 2014: LA3024 EU Law - Zone ADocument9 pagesExaminers' Report 2014: LA3024 EU Law - Zone AJUNAID FAIZANNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary SovereigntyDocument6 pagesParliamentary SovereigntyChaucer WongNo ratings yet

- European Union I Law Lecture NotesDocument8 pagesEuropean Union I Law Lecture NotesAlex0% (1)

- European Citizenship Is Just A Grand Term That Brings Nothing Much More To The Nationals of The EU Member States Than What They Already HadDocument2 pagesEuropean Citizenship Is Just A Grand Term That Brings Nothing Much More To The Nationals of The EU Member States Than What They Already HaduzeeNo ratings yet

- Examiners' Reports 2017: LA3024 EU Law - Zone ADocument11 pagesExaminers' Reports 2017: LA3024 EU Law - Zone AFahmida M RahmanNo ratings yet

- Competition PolicyDocument12 pagesCompetition PolicyMehreenNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument9 pagesCorporate Social ResponsibilityMartijn ReekNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Freedom of EstablishmentDocument5 pagesChapter 7 - Freedom of EstablishmentMehreenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1.7 - Other InstitutionsDocument3 pagesChapter 1.7 - Other InstitutionsMehreenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Free Movement of WorkersDocument13 pagesChapter 4 - Free Movement of WorkersMehreenNo ratings yet

- Human Rights in The EU (10469)Document21 pagesHuman Rights in The EU (10469)MehreenNo ratings yet

- Adverse PosessionDocument6 pagesAdverse PosessionMehreenNo ratings yet

- Citizenship of The EUDocument8 pagesCitizenship of The EUMehreenNo ratings yet

- Competition PolicyDocument12 pagesCompetition PolicyMehreenNo ratings yet

- Free Movement of GoodsDocument14 pagesFree Movement of GoodsMehreen100% (1)

- CertaintiesDocument6 pagesCertaintiesMehreenNo ratings yet

- Amniocentesis Procedure OverviewDocument6 pagesAmniocentesis Procedure OverviewYenny YuliantiNo ratings yet

- Enrile Vs AminDocument2 pagesEnrile Vs AminManuel Joseph Franco100% (2)

- DE 283 Comp Rel-ODocument10 pagesDE 283 Comp Rel-ODavid Oscar MarkusNo ratings yet

- Camaya Vs PatulandongDocument5 pagesCamaya Vs PatulandongJesstonieCastañaresDamayoNo ratings yet

- Far East Bank (FEBTC) Vs Pacilan, Jr. (465 SCRA 372)Document9 pagesFar East Bank (FEBTC) Vs Pacilan, Jr. (465 SCRA 372)CJ N PiNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3Document69 pagesAssignment 3Era Yvonne KillipNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. Jose Belmar Umapas Y Crisostomo GR. No. 215742, March 22, 2017 FactsDocument1 pagePeople of The Philippines vs. Jose Belmar Umapas Y Crisostomo GR. No. 215742, March 22, 2017 FactsdnzrckNo ratings yet

- Allan Bullock - Hitler & Stalin - Parallel LivesDocument15 pagesAllan Bullock - Hitler & Stalin - Parallel LivesOnur Kizilsafak0% (2)

- Notwithstanding, The Retirement Benefits Received by Officials and Employees ofDocument2 pagesNotwithstanding, The Retirement Benefits Received by Officials and Employees ofSalma GurarNo ratings yet

- Bank Liability for Dishonored ChecksDocument22 pagesBank Liability for Dishonored ChecksbictorNo ratings yet

- Conflicts of Law ChartDocument8 pagesConflicts of Law ChartJoAnne Yaptinchay ClaudioNo ratings yet

- Norfolk & Western Railway Company, Plff. in Err. v. W. G. Conley, Attorney General of The State of West Virginia, 236 U.S. 605 (1913)Document6 pagesNorfolk & Western Railway Company, Plff. in Err. v. W. G. Conley, Attorney General of The State of West Virginia, 236 U.S. 605 (1913)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Liddell Hart - The Ghost of NapoleonDocument194 pagesLiddell Hart - The Ghost of Napoleonpeterakiss100% (1)

- M LUTHER KING Um Apelo A Consciencia - Os Mel - Clayborne CarsonDocument13 pagesM LUTHER KING Um Apelo A Consciencia - Os Mel - Clayborne CarsonMarçal De Menezes ParedesNo ratings yet

- Vu Tra Giang - 20070149 - INS3022 - 02Document7 pagesVu Tra Giang - 20070149 - INS3022 - 02Hương GiangNo ratings yet

- Court Fees Are For Persons-Persons Are Not PeopleDocument45 pagesCourt Fees Are For Persons-Persons Are Not PeopleDavid usufruct GarciaNo ratings yet

- Ajisaka Short StoryDocument3 pagesAjisaka Short StoryErikca G. Fernanda100% (1)

- St. John's E.M High School: Class: IVDocument5 pagesSt. John's E.M High School: Class: IVsagarNo ratings yet

- Contract of Lease Buenaventura - FinalDocument3 pagesContract of Lease Buenaventura - FinalAndrew BenitezNo ratings yet

- Terry Mallenby Successfully Sued The Royal Canadian Mounted Police - Received $275,000 Out-Of-court Settlement!Document106 pagesTerry Mallenby Successfully Sued The Royal Canadian Mounted Police - Received $275,000 Out-Of-court Settlement!WalliveBellairNo ratings yet

- RTI Manual BD PDFDocument2 pagesRTI Manual BD PDFShushant RanjanNo ratings yet

- State v. Danna WeimerDocument34 pagesState v. Danna WeimerThe News-HeraldNo ratings yet

- NEAJ Article on AraquioDocument4 pagesNEAJ Article on AraquioChristian Edezon LopezNo ratings yet

- An Institutional History of The LTTEDocument96 pagesAn Institutional History of The LTTEeelamviewNo ratings yet

- 1.top 30 Essays Zahid Ashraf Jwtimes - p011Document1 page1.top 30 Essays Zahid Ashraf Jwtimes - p011Fahad KhanNo ratings yet

- MOV Act 3 Scene 3 Question and AnswerDocument3 pagesMOV Act 3 Scene 3 Question and AnswerAditya SinhaNo ratings yet

- List of Allotted Candidates Institute Wise For NEET UG Counseling-2019 2019 (017) Govt. Medical College, Ambedkarnagar (Govt.) Co-EducationDocument3 pagesList of Allotted Candidates Institute Wise For NEET UG Counseling-2019 2019 (017) Govt. Medical College, Ambedkarnagar (Govt.) Co-EducationDev Raj SinghNo ratings yet

- Epstein v. Epstein Opening Brief 1Document23 pagesEpstein v. Epstein Opening Brief 1Jericho RemitioNo ratings yet