Professional Documents

Culture Documents

015 Tech Transfer Learn From USA

Uploaded by

Mohit SinghalCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

015 Tech Transfer Learn From USA

Uploaded by

Mohit SinghalCopyright:

Available Formats

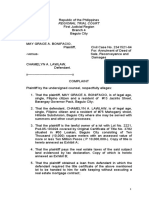

Journal of Intellectual Property Rights

Vol 10, September 2005, pp 399-405

Technology Transfer: What India can learn from the United States

Kelly G Hyndman, Steven M Gruskin and Chid S Iyer

Sughrue Mion PLLC, 2100 Pennsylvania Ave, NW, Washington DC 20037, USA

Received 4 August 2005

Indian universities and government-funded research organizations produce world-class research that is mostly

published in scientific journals. While the society gains from the increased knowledge, the university or the government

receives very little direct benefit. Developed countries like the United States have been encouraging similar institutions to

secure their intellectual property rights in the new technology arising out of the research in addition to merely publishing in

scientific journals. The United States has a long history of supporting technical research and has gradually evolved to this

model. India should learn from the experience of the United States in this regard. Premier institutions of learning and

research in the United Sates provide effective models that use patents and their licensing as tools for technology transfer

This paper discusses a brief history of tech transfer in the United States, followed by a discussion of the Bayh-Dole Act,

which served as a catalyst for the successful tech transfer regime in effect today. Various aspects of IP ownership are

discussed, followed by a relevant case study.

Keywords: Technology transfer, Bayh-Dole Act, IP ownership

India has a vast network of publicly owned research

and development facilities. The numerous laboratories

under the CSIR umbrella, the IITs, the IISc, TIFR,

BARC, etc, produce world class research in various

technology areas of importance to mankind. Like their

counterparts in the rest of the world, publishing peerreviewed scientific papers and/or generating technical

reports for internal use have been the primary means

of disseminating this information or transferring

technology. While adding to scientific glory and

prestige, these institutions and the Indian government

have gained little in terms of direct economic benefits.

In most developed economies and in fast

developing

economies,

advanced

research,

development and technical expertise coming out of

universities and research organizations needs to be

transferred for the public good. It is amply clear that

such institutions, in addition to providing for the

public good, support local governments in business

development. On the other hand, in todays

knowledge-based economy, universities and research

organizations require both capital and knowledge. To

continue the support provided by the government as

well as to return some of the direct benefits to the

public, initiatives and incentives are required for these

institutions to fully capitalize on the technology they

produce.

________

Email: ciyer@sughrue.com

India can learn from the United States history of

technology transfer and the initiatives provided by the

United States government, for example, the BayhDole Act, that served as a catalyst for such technology

transfer. A developing economy like India should

benefit from the experiences of the United States in

formulating a technology transfer policy.

A Brief History of Tech Transfer in the US

For over a hundred years, the United States has

been supporting public universities, which in turn

have served as an impetus to research and

development. In 1862, the United States passed the

Morrill Act1. According to this Act, the United States

government started allocating 30,000 acres of public

land in each state to establish land grant colleges,

thereby offering patronage to research and

development performed by these universities. A key

interest of the government was the consolidation of

agricultural, economic, military and research interests

as well as solidifying the economic infrastructure. The

Morrill Act played a significant role in achieving this

goal. In 1890, the Morrill Act was further

strengthened with endowments and support provided

to agricultural and mechanical arts. In addition, land

grants were provided to additional states mainly in the

south2. The Morrill Act thus provided a boost to

research and served as a means of technology transfer

400

J INTELLEC PROP RIGHTS, SEPTEMBER 2005

and economic development activities. Increasingly,

the scientific community started viewing knowledge

as a commodity in addition to using it to satisfy

intellectual curiosity3. In addition, while resources

provided by the government acted as a catalyst,

universities also started attracting research funding

from private entities such as corporations.

At the time of Morrill Act, the only means of

effecting technology transfer to the public was by

way of publications. Researchers were required to

perform research in an unbiased way and publish it

for the common good. While researchers accepted

grants as a necessary evil, accepting royalties for the

knowledge generated was considered taboo. A few

important issues arose at this point. A broad issue was

whether universities should allow commercial forces

to determine their research and academic missions.

Should the universities allow the sponsors of research

to dictate the terms of research or influence the

research. If private entities, such as, corporations are

funding the research, should the universities follow a

research agenda that is guided by these private

entities.

What the purists feared most started happening,

slowly but surely. Private entities, especially,

corporations that once gave unrestricted money to

colleges to cultivate good will, started backing

projects based principally on their commercial worth.

In addition, corporations started asking for first rights

of refusal and at times exclusive rights to the

intellectual property arising out of the research. To

cope with this demand and to share in the benefits,

universities began to file for and obtain patents, and

began opening technology-licensing offices.

The University of Wisconsin was one of the first

universities to begin this trend by establishing a plan

in 1924 to license patents generated by its faculty.

The intense financial pressure generated by great

depression of the 1930s further sparked the interest of

the universities in obtaining patents and generating

revenues. The technological demands imposed by the

second World War could not be met without the

support of the universities. The additional funding

resulting from war related research provided further

impetus to commercializing and generating revenues

out of university inspired inventions. The

government, in turn, played its part in increasingly

sponsoring research by the universities. A major issue

in this regard was whether the government should

secure the commercial rights to patentable inventions

for themselves or leave it to the patentees4.

In 1941, the Office of Scientific Research and

Development was established to coordinate weapons

research and to advise on scientific research and

development. Dr Vannevar Bush served as the

chairman. An important contribution of the office was

the very successful two billion dollar Manhattan

Project. After Dr Bush became President Roosevelt's

Science Advisor, he was asked to come up with

proposals for applying the lessons learned during

wartime to civilian use. Having witnessed the benefits

of university research to the Manhattan Project, Dr

Bush recommended using university research in

civilian applications. To achieve this goal, Dr Bush

argued for an increase in support by the federal

government for scientific research at universities5,6.

At the same time, universities were becoming more

sophisticated in their technology transfer programme,

even in areas where there was a lack of governmentsponsored research. After the war, universities started

concentrating more on fundamental and long-term

research issues. In 1950, Congress established the

National Science Foundation (NSF) to support basic

scientific research at universities. It was becoming

clear that transferring inventions created in the

universities to the private sector for commercial use

was essential to future economic growth and global

business competitiveness. While the NSF was aimed

at providing grants to research organizations, the

Federal Government started allocating resources to

find cures for diseases and eventually created the

National Institute of Health (NIH)7. However, because

of the Cold War, which reached its peak in the

1960s, the Federal Government's dependence on

university research in areas other than medical

research increased. In the 1960s, the need for a

government-wide policy on inventions and patents

was beginning to be felt. President Kennedys

scientific advisor, Dr Weisner, proposed establishing

government-wide objectives and criteria for allocating

legal rights to inventions between the government,

which funded the research, and the contractors, who

actually performed the research.

As another example of the trend for technology

transfer, Stanford University in California started

granting extended leases of the universitys land to

high tech companies. Long before the start of recent

Silicon Valley revolution and the New Economy,

the Stanford Industrial Park was founded to create a

HYNDMAN et al: TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER: WHAT INDIA CAN LEARN FROM THE UNITED STATES

centre of high technology close to a cooperative

university8. Today, it is estimated that eleven new

companies are being created every week in Silicon

Valley, which is nearby to Stanford University9.

By the 1970s, the United States was experiencing

a shift towards a more service-oriented economy. The

erstwhile manufacturing states like Illinois, Michigan,

Ohio, and Pennsylvania were suffering economically.

Major recessions led to manufacturing industries

being closed, unemployment, emigration from the

affected states, and an overall decline in prosperity.

To counter this trend, several states tried opening

business incubators to foster economic development

through job growth. These incubators lead to some

revitalization. Even with this revitalization, there were

fewer than ten incubators open in the US by 1980.

The passage of the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 changed

the landscape completely.

The Bayh-Dole Act

The Bayh-Dole Act provided impetus to university

licensing offices to use start-up companies to

commercialize early stage inventions10. Hundreds of

start-up companies have resulted from this impetus.

The Bayh-Dole Act was passed to address concerns

about declining US productivity. The rising

competition from Japan alarmed legislators. Further,

they were receiving complaints regarding the

government's inconsistent treatment of contracted

inventions. The Act was a combination of many

policy goals and sought to establish a uniform patent

policy within the government. The Act essentially

changed the presumption of title to any invention

made using government funds from the government to

the contractor or patentee that actually created the

invention11.

Whenever there is a contract, grant, or cooperative

agreement between any federal agency and any

contractor for the performance of experimental,

developmental, or research work, provisions of the

funding agreement under the Bayh-Dole Act are

implicated. The project could be funded fully or only

in part by the federal government. The inventors

associated with the project are required to promptly

disclose their inventions. If the institution where the

inventors perform the research fails to notify the

government within two months of disclosure,

according to the Bayh-Dole Act, the title could pass

on to the government. If the university does not retain

title within two years, then title vests with the

401

government. Inventors may also petition the funding

agency to obtain title to the invention. The titleholder

must file for a patent within one year of electing title.

In certain areas that are government-dominated like

aerospace and defense, the government retains rights

to the invention. According to the Bayh-Dole Act, the

titleholder can license, but not assign, rights to others.

Also, licensees are required to exploit the technology

and produce the goods and services in the US. The

royalties must be shared with the inventors.

The government receives a large number of

proposals for grants that are themselves a significant

source of scientific knowledge. This is because BayhDole Act requires publication of these proposals. If

the knowledge disclosed in these proposals is not

protected as confidential, the corresponding

publications can even be used as prior art against a

patent applicant.

Congress passed a series of amendments to the

Bayh-Dole Act in 1984, which extended its provisions

to inventions originating at government-owned,

contractor-operated facilities. It also repealed

limitations on the permissible duration of licenses

from nonprofit organizations to large businesses for

government-sponsored inventions. In 1986, the

Federal Technology Transfer Act was passed which

authorized federal laboratories to enter into

cooperative research and development agreements

(CRADAs) with outside entities12. The laboratories

were allowed to agree in advance to assign or license

any patents on inventions made by federal employees

in the course of collaborative research to the

collaborating party.

It is clear that the 1980s signaled the start of a propatent trend in the United States. Subsequent

legislation continued to broaden and fortify the propatent policy. It is virtually guaranteed today that

regardless of whether federally-sponsored inventions

are made directly by the government or by

universities and private entities using government

funding, anyone involved in the research project who

wants the technology to be patented will prevail over

the objections of anyone else who argues that the

technology should be placed in the public domain. A

sponsoring agency may insist on obtaining a patent

even if a university is reluctant to patent an invention

made in its laboratories with federal funds.

In cases where the government expresses its

disinterest in pursuing a patent, the individual

inventor(s) can file for patents on his or her own.

402

J INTELLEC PROP RIGHTS, SEPTEMBER 2005

Such a policy has been justified as a means of

improving productivity in American industry and

ensuring that the results of taxpayer-supported

research are translated into useful products and

processes.

Transfer of patent ownership to the research

partner outside the government that started with the

passage of the Bayh-Dole Act, sparked a technology

transfer boom in the early eighties. Research and

academic institutions started technology transfer

programs and generating licensing income and spinoff companies. Bayh-Dole continues to have broad

implications in a large part due to the fact that federal

funding is today still a significant source of revenue

for US universities and research institutions. In 1996,

the Association of University Technology Managers

(AUTM) estimated that the licensing activities of

academic institutions, nonprofit organizations, and

patent management firms add more than 24.8 billion

dollars and 212,500 jobs to the US national economy

each year.

The Bayh-Dole Act fostered a new era in the

relationship between the government and universities.

The Act permits universities to establish and/or

expand technology transfer capabilities. The number

of academic institutions receiving patents increased

from 75 in the 1980s to 175 by 1997. Such a trend in

patenting by universities simply reflects the

importance of academic research to economic

activity. While obtaining patents is a measure of tech

transfer, the real measure is the amount of patented

technology that has been transferred to the private

sector for further development into commercially

viable products and processes that society finds

useful. In this regard, patent licenses and other

transfers of technology have increased steadily since

the passage of the Bayh-Dole Act.

IP Ownership by Universities

Universities today generate a large number of

ventures in collaboration with industry. Industrysponsored research, business incubators, and spin-off

companies provide revenue-generating opportunities

to the universities. While these collaborations are

undoubtedly fruitful, they can also be difficult. These

difficulties are rooted in the guiding principles of the

existence of these entities. Universities believe in

sharing

knowledge,

whereas

maintaining

confidentiality is a key to running businesses.

Universities have the public goal of educating the

masses, whereas corporations and other private

ventures exist to create profits. An effective

technology transfer policy must manage these

divergent interests. The institution's core values and

principles must be considered in determining how

best to manifest them in its IP management policies

and practices.

Two key ways to transfer technology are the use of

license agreements and the establishment of new

ventures.

License agreements can be used to exploit

intellectual property (IP), such as patents. Patents are

a critical component of any IP management policy

because they provide the holder a property right in

return for public disclosure of the invention. They can

also be used as a metric to evaluate innovation at the

institution. Being deeds of property rights, they come

with special legal considerations and requirements.

Patents form the core of any related license that in

turn generates revenue.

Universities can also help establish new ventures as

they foster the spirit of entrepreneurship at any

institution. They motivate faculty and student

entrepreneurs and, while requiring investment, create

wealth for the stakeholders. Because of this, they have

the potential to create various conflicts of interest.

Both patents and new ventures are assets that result

from innovations created within the university with

the involvement of faculty and students. Therefore,

the issues of ownership and control of these assets

become critical. Several important issues need to be

considered to successfully and strategically manage

patents and new ventures. It should be decided early

on who the owners of the patents will be and who will

make licensing decisions and on what terms. Since the

cost of obtaining patents is great, it must be decided

who will fund the process of patenting and licensing.

Likewise, in the event of a potential windfall, a

revenue sharing plan must be put in place from the

beginning. For new ventures, it must be decided what

level of involvement the institution will have and

what financial and management stake the institution

will hold.

Issues of ownership and control must also be

decided. A common model is that the institute owns

any IP created by faculty and students. In such cases,

an employment agreement clarifies the ownership.

The employee is required to promptly disclose

inventions or improvements assist in the patenting

process, and execute all required documents for patent

HYNDMAN et al: TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER: WHAT INDIA CAN LEARN FROM THE UNITED STATES

prosecution. Universities often use this model for

their own faculty/student inventors. Universities using

this model should include all the relevant

requirements in the faculty employment agreement. In

addition, the employment agreement should also

include terms for termination, compensation, etc.

If the university does not use employment

agreements, common law will determine ownership of

inventions.

In

general,

ownership

follows

inventorship. It is also established that the rights of

ownership belong to the employer only if the

employee was hired to invent, and that the employer

has the burden of proving the employee was hired to

create the particular invention that is the subject of a

dispute.

Case Study: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

is known around the world as a leader in the

development of technology. Does MITs means of

technology transfer live up to its formidable

reputation as a leading academic institution? In some

ways, the answer is yes. The final judgment on MITs

particular implementation of a technology transfer

programme will be left to the reader. At the very least,

peeking into a concrete implementation at a key

American institution will provoke at least some

retrospection as to the applicability of the ideas in

other settings13.

The programme at MIT is implemented in large

measure by the MIT Technology Licensing Office

(TLO), which has two principal goals. The first is to

facilitate the transfer to public use and benefit of the

technology developed at MIT. The second goal,

subordinate at least in theory to the first, is to provide

an additional source of unrestricted income to support

research and education at MIT. The TLO is not an end

in itself, but aspires to work towards its goals without

interfering with the normal routine of preparation and

publication of technical and academic information.

The TLO has the responsibility to recommend and

disseminate the policies that implement the

technology transfer programme. The policies are

naturally those of the university, not those of the

TLO, which is just an office in the university

infrastructure charged with such responsibilities.

At a university as large and diverse in focus as

MIT, it is not surprising that technologycan mean

anything and everything, and technology transfer is

not limited to obtaining patents or to minding

403

copyrights. In many instances, the distribution and

commercialization of technology is accomplished by

the transfer or licensing of the intellectual property

rights, such as patents and copyrights, but this is not

the end of the story. The distribution and

commercialization of technology also depends, at

times, on access to the embodiment of the technology:

biological organisms, plant varieties or computer

software. In view of this, the policies of the TLO need

to cover not only the ownership, distribution, and

commercialization rights associated with the

technology in the form of intellectual property, but

also the use and distribution of the technology in its

tangible form.

The TLO provides information about patents. This

information is not only the general description of

patents and rights, and the procedures for obtaining

them in the United States, but also some important

insights and cautions regarding safeguarding and

obtaining patent rights outside the United States.

Similarly, the TLO policy statements provide

descriptive and procedural information concerning,

inter alia, copyrights, trademarks, service marks,

trade secrets, mask works, and research materials such

as those mentioned above.

With regard to trade secrets, it should be noted that

the university is not itself normally engaged in the

protection of their own trade secrets, but it is

recognized that research at the university may involve

cooperating with outside institutions, and that the

duties and responsibilities for protecting trade secret

information must be understood by the people from

MIT that are involved. Since trade secrets are ideally

not included in a technology transfer programme from

the standpoint of making such secrets available to the

public, trade secrets of cooperating institutions should

be one of the things that a good technology transfer

program takes into account in the best way possible.

At MIT, as in other institutions, there is recognition

of the tension inherent in a technology transfer

programme that has, as one of its goals, the

accumulation of funds for the good of the university.

This inherent tension comes about from the goal of

free, frank, and fast information transfer among

scholars, in equipoise with the goal of the protection

of ownership and development rights. In such a builtin conflict, there can be only one head of the

household, only one of these goals that reigns

supreme. At MIT, the balance is intentionally tipped

404

J INTELLEC PROP RIGHTS, SEPTEMBER 2005

towards the side of forwarding education and research

instead of the side of profit and ownership.

As to ownership, however, MIT makes it clear

where the university stands. The university policy is

that patents, copyrights on software, mask works,

tangible research property, and trademarks developed

by faculty, students, staff and others, including

visitors participating in MIT programmes or using

MIT funds or facilities, are owned by MIT when the

intellectual property was developed in the course of,

or pursuant to, a sponsored research agreement with

MIT; or the intellectual property was developed with

significant use of funds or facilities administered by

MIT. Also, MIT states that it owns all copyrights,

including copyrighted software, when it is created as a

work of hire under the US copyright laws; or when

it is created pursuant to a written agreement with MIT

providing for transfer of copyright or ownership to

MIT.

The MIT policy also sets out when an invention or

other IP is owned by the inventor or author. This is an

important aspect of a good technology transfer

programme. In other words, it is just as important to

define when the institution owns something as it is to

set forth when the institution does not own something.

At MIT, the inventor or author owns the rights

whenever MIT does not own them. Of course,

research contracts sponsored by the Federal

Government are subject to the statutes and regulations

already mentioned above.

Earlier, it was mentioned that MIT owns the IP

when the IP was developed with significant use of

funds or facilities administered by MIT. Drilling

deeper for more insight, however, reveals that there

could be significant disagreement as to what

constitutes a significant enough use of funds or

facilities to convey ownership to MIT. Accordingly,

the technology transfer programme at MIT goes to

some length to set forth points that can be used as

navigational beacons to safely chart ones course

through what might be otherwise murky waters.

Generally, an invention, software, or other

copyrightable material, mask work, or tangible

research property will not be considered to have been

developed using MIT funds or facilities if the

following four conditions are all true: (1) only a

minimal amount of unrestricted funds have been used;

and (2) the invention, software, or other copyrightable

material, mask work, or tangible research property has

been developed outside of the assigned area of

research of the inventor/author under a research

assistantship or sponsored project; and (3) only a

minimal amount of time has been spent using

significant MIT facilities or only insignificant

facilities and equipment have been utilized; and (4)

the development has been made on the personal,

unpaid time of the inventor/author. For the sake of

even greater clarity, MIT agrees that the use of office,

library, machine shop facilities, and of traditional

desktop personal computers are examples of facilities

and equipment that are not considered significant.

When IP has been developed using significant MIT

funds or facilities but is not the subject of a research

agreement, the policy for technology transfer at the

university provides that the TLO may license the

inventors exclusively or nonexclusively on a royalty

basis. This licensing does not happen in every case,

but is likely to occur where the inventors demonstrate

technical and financial capability to commercialize

the IP. Commercialization should be achieved within

a period of a few years, or the inventors are deemed to

have waived their rights to the royalties and the TLO

will terminate their license.

As one might expect, the university clearly

disclaims any right to an interest in the ownership of

books, articles and other scholarly publications, or to

popular novels, poems, musical compositions, or

other works of artistic imagination which are created

by the personal effort of faculty, staff and students

outside of their assigned area of research and which

do not make significant use of MIT administered

resources.

MIT does give its faculty an incentive to seek and

obtain patents, on two levels. A list of patents

awarded appears on the faculty personnel record,

although this may not be as prestigious as

publications in peer-reviewed journals when it comes

to tenure/promotion. Financially, there is revenue

sharing on licensing fees as mentioned before. A

percentage goes to MIT; a percentage may also be

paid to the inventor's group (lab or department) and a

percentage to the inventor. In addition, the faculty

gets to own and exploit the patent if the institution

determines that it has no such interest. The faculty

member files an invention disclosure with the TLO,

which reviews it. If the TLO decides that MIT is not

interested, they may even assign the rights to the

inventor to do with them as he wishes. The inventor

then has full control of the IP. Interestingly, MIT as a

matter of routine policy will not seek protection for

HYNDMAN et al: TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER: WHAT INDIA CAN LEARN FROM THE UNITED STATES

inventions, which are not commercially attractive,

even if the invention is intellectually meritorious.

Having glimpsed into a few of the many aspects of

the MIT technology transfer program, it is easy to see

the high level of importance this institution places on

technology transfer. The ownership of IP certainly

appears on the balance to favour a presumption that

the university owns more than it does not own.

Nevertheless, the policy provides incentives, both

professional and monetary, to encourage innovation

and technology transfer.

Conclusion

India has spent significant amounts of public

resources from the beginning of its independence and,

in some cases, even before, in establishing world class

research institutions and supporting them with ample

resources. It is critical that the technology developed

by these institutions is commercialized and that the

direct benefits are returned to the government and/or

to society. An effective technology transfer policy

will go a long way in achieving that objective. The

United States has a long history in supporting

technology research and utilizing the results

commercially. India should draw on the experience

405

and history of technology transfer in the United States

to help it establish its own effective technology

transfer policy.

References

1 7 U.S.C. 301 et seq

2 7 U.S.C 322

3 Vincent Gregory J, Reviving the land-grant idea through

community-university partnerships, 31 Southern University

Law Review, 1 (2003)

4 Siepmann Thomas J, The global exportation of the US BayhDole Act, 30 Dayton Law Review, 209

5 Klaphaak David K, Events in the life of Vannevar Bush,

http://graphics.cs.brown.edu/html/info/timeline.html

6 Malone Erin, Foreseeing the future: The legacy of Vannevar

Bush, http://www.boxesandarrows.com/archives/foreseeing

the_future_the_legacy_of_vannevar_bush.php

7 The NIH Almanac, http://www.nih.gov/about/almanac/

8 Gromov Gregory, A few quotes from Silicon Valley history,

http://www.netvalley.com/svhistory.html

9 http://www.netvalley.com/

10 35 U.S.C. 200 et seq

11 Hamilton Clovia, University technology transfer and

economic development: proposed cooperative economic

development agreements under the Bayh-Dole Act, 36 John

Marshall Law Review 397

12 15 U.S.C. 1501 et seq

13 http://www.mit.edu/afs/athena/org/t/tlo/www/guide.pdf

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Enochian Tablets ComparedDocument23 pagesEnochian Tablets ComparedAnonymous FmnWvIDj100% (7)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Petrosian System Against The QID - Beliavsky, Mikhalchishin - Chess Stars.2008Document170 pagesThe Petrosian System Against The QID - Beliavsky, Mikhalchishin - Chess Stars.2008Marcelo100% (2)

- Basic of PackagingDocument40 pagesBasic of PackagingSathiya Raj100% (1)

- 78 Complaint Annulment of Documents PDFDocument3 pages78 Complaint Annulment of Documents PDFjd fang-asanNo ratings yet

- The Wooden BowlDocument3 pagesThe Wooden BowlClaudia Elisa Vargas BravoNo ratings yet

- Matalam V Sandiganbayan - JasperDocument3 pagesMatalam V Sandiganbayan - JasperJames LouNo ratings yet

- Quickstart V. 1.1: A Setting of Damned Souls and Unearthly Horrors For 5 EditionDocument35 pagesQuickstart V. 1.1: A Setting of Damned Souls and Unearthly Horrors For 5 EditionÁdám Markó100% (2)

- WAS 101 EditedDocument132 pagesWAS 101 EditedJateni joteNo ratings yet

- Paintindia 2016 Exhibitor ListDocument12 pagesPaintindia 2016 Exhibitor ListMohit Singhal0% (1)

- Visitor Visas For Your FamilyDocument4 pagesVisitor Visas For Your FamilyMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- C75 GunJet Low-Pressure BDocument10 pagesC75 GunJet Low-Pressure BMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Residential Facilities Er - Go: General RulesDocument30 pagesResidential Facilities Er - Go: General RulesMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Keyence vhx-6000 ManualDocument360 pagesKeyence vhx-6000 ManualMohit Singhal0% (1)

- Our Commitment To Our Plan Members: Your Group Insurance PlanDocument23 pagesOur Commitment To Our Plan Members: Your Group Insurance PlanMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Keyence vhx-6000 ManualDocument360 pagesKeyence vhx-6000 ManualMohit Singhal0% (1)

- Experimental Use of Line-X Coated Steel Piles Mousam RiverDocument29 pagesExperimental Use of Line-X Coated Steel Piles Mousam RiverMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Ielts 42 Topics For Speaking Part 1Document32 pagesIelts 42 Topics For Speaking Part 1Zaryab Nisar100% (1)

- Is 101 7 4 1990Document9 pagesIs 101 7 4 1990Mohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Coat HidrofobicoDocument52 pagesCoat HidrofobicoherfuentesNo ratings yet

- NSCC Brochure WebDocument8 pagesNSCC Brochure WebMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- 015 Tech Transfer Learn From USADocument7 pages015 Tech Transfer Learn From USAMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Paints and PigmentsDocument19 pagesPaints and PigmentsbaanaadiNo ratings yet

- BlackDocument2 pagesBlackMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Bangalore To House India's First Nano Park - EE TimesDocument4 pagesBangalore To House India's First Nano Park - EE TimesMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Nano Scale ScienceDocument23 pagesNano Scale ScienceMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Civil Engineer Sample Resume: Professional ExperienceDocument1 pageCivil Engineer Sample Resume: Professional ExperienceRencyNo ratings yet

- SyllabusDocument38 pagesSyllabusहुडदंग हास्य कवि सम्मलेनNo ratings yet

- Bopp 1Document16 pagesBopp 1Mohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Nanotechnology Companies in India - Nanoall - Nanotechnology BlogDocument3 pagesNanotechnology Companies in India - Nanoall - Nanotechnology BlogMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- EvonikDocument20 pagesEvonikMohit Singhal0% (1)

- Paint India DR Industry Summary 2011Document24 pagesPaint India DR Industry Summary 2011anandgoud11No ratings yet

- What Is PaintDocument5 pagesWhat Is PaintDan MillerNo ratings yet

- Ewaste Registration ListDocument12 pagesEwaste Registration ListDiprajSinhaNo ratings yet

- What To Declare at The Customs While Travelling Abroad - Timesofindia-EconomictimesDocument3 pagesWhat To Declare at The Customs While Travelling Abroad - Timesofindia-EconomictimesMohit SinghalNo ratings yet

- List PatentAgent April 2010Document188 pagesList PatentAgent April 2010Gnanesh Shetty BharathipuraNo ratings yet

- Option Valuation and Dividend Payments F-1523Document11 pagesOption Valuation and Dividend Payments F-1523Nguyen Quoc TuNo ratings yet

- Final Annexes Evaluation Use Consultants ApwsDocument51 pagesFinal Annexes Evaluation Use Consultants ApwsSure NameNo ratings yet

- Monopolistic CompetitionDocument4 pagesMonopolistic CompetitionAzharNo ratings yet

- Department of Planning and Community Development: Organizational ChartDocument5 pagesDepartment of Planning and Community Development: Organizational ChartkeithmontpvtNo ratings yet

- Equilibrium Is A 2002 American: The Flag of Libria. The Four Ts On The Flag Represent The Tetragrammaton CouncilDocument5 pagesEquilibrium Is A 2002 American: The Flag of Libria. The Four Ts On The Flag Represent The Tetragrammaton CouncilmuhammadismailNo ratings yet

- Final Technical Documentation: Customer: Belize Sugar Industries Limited BelizeDocument9 pagesFinal Technical Documentation: Customer: Belize Sugar Industries Limited BelizeBruno SamosNo ratings yet

- Superstitions, Rituals and Postmodernism: A Discourse in Indian Context.Document7 pagesSuperstitions, Rituals and Postmodernism: A Discourse in Indian Context.Dr.Indranil Sarkar M.A D.Litt.(Hon.)No ratings yet

- Witherby Connect User ManualDocument14 pagesWitherby Connect User ManualAshish NayyarNo ratings yet

- Module 7: Storm Over El Filibusterismo: ObjectivesDocument7 pagesModule 7: Storm Over El Filibusterismo: ObjectivesJanelle PedreroNo ratings yet

- 1ST Term J3 Business StudiesDocument19 pages1ST Term J3 Business Studiesoluwaseun francisNo ratings yet

- IGNOU Vs MCI High Court JudgementDocument46 pagesIGNOU Vs MCI High Court Judgementom vermaNo ratings yet

- Bos 2478Document15 pagesBos 2478klllllllaNo ratings yet

- Company Analysis of Axis BankDocument66 pagesCompany Analysis of Axis BankKirti Bhite100% (1)

- Top 7506 SE Applicants For FB PostingDocument158 pagesTop 7506 SE Applicants For FB PostingShi Yuan ZhangNo ratings yet

- Bond by A Person Obtaining Letters of Administration With Two SuretiesDocument2 pagesBond by A Person Obtaining Letters of Administration With Two Suretiessamanta pandeyNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7 - Conditions of Employment Pt. 2Document55 pagesLecture 7 - Conditions of Employment Pt. 2Steps RolsNo ratings yet

- 45-TQM in Indian Service Sector PDFDocument16 pages45-TQM in Indian Service Sector PDFsharan chakravarthyNo ratings yet

- Cadila PharmaDocument16 pagesCadila PharmaIntoxicated WombatNo ratings yet

- Special Power of Attorney: Know All Men by These PresentsDocument1 pageSpecial Power of Attorney: Know All Men by These PresentsTonie NietoNo ratings yet

- Test 5Document4 pagesTest 5Lam ThúyNo ratings yet

- British Airways Vs CADocument17 pagesBritish Airways Vs CAGia DimayugaNo ratings yet

- Wendy in Kubricks The ShiningDocument5 pagesWendy in Kubricks The Shiningapi-270111486No ratings yet

- My Portfolio: Marie Antonette S. NicdaoDocument10 pagesMy Portfolio: Marie Antonette S. NicdaoLexelyn Pagara RivaNo ratings yet