Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lucien M. Aubut v. State of Maine, 431 F.2d 688, 1st Cir. (1970)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lucien M. Aubut v. State of Maine, 431 F.2d 688, 1st Cir. (1970)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

431 F.

2d 688

Lucien M. AUBUT, Petitioner,

v.

STATE OF MAINE et al., Respondents.

Misc. No. 412.

United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit.

September 23, 1970.

Lucien M. Aubut, pro se.

Before ALDRICH, Chief Judge, McENTEE and COFFIN, Circuit Judges.

ALDRICH, Chief Judge.

Petitioner, having been convicted in the state court of uttering a forged

instrument, and having unsuccessfully appealed, State v. Aubut, Me., 1970, 261

A.2d 48, sought habeas corpus relief in the district court. His petition was

dismissed without hearing. A certificate of probable cause for appeal having

been denied by that court, he appropriately renews the request here. Local Rule

11. Petitioner also seeks the appointment of counsel, and other preliminary

relief.

We do not accept "notice" pleading in habeas corpus proceedings. Were the

rule otherwise, every state prisoner could obtain a hearing by filing a complaint

composed, as is the present one, of generalizations and conclusions. The

petition should set out substantive facts that will enable the court to see a real

possibility of constitutional error. Habeas corpus is not a general form of relief

for those who seek to explore their case in search of its existence.

Nor, alternatively, will we appoint counsel to make such a search for an

indigent prisoner who is unable to file a complaint that shows a reasonable

possibility of error. Joyce v. United States, 1 Cir., 1964, 327 F.2d 531;

Anderson v. Heinze, 9 Cir., 1958, 258 F.2d 479, cert. denied 358 U.S. 889, 79

S.Ct. 131, 3 L.Ed.2d 116; cf. Johnson v. Avery, 1969, 393 U.S. 483, 488, 89

S.Ct. 747, 21 L.Ed.2d 718. Possibly this is a hardship in rare cases, but,

judicially, we regard the "cure" to be excessive. All discontented prisoners

ignorant of the presence of constitutional error, but ever hopeful, would make

such a request. Inadequately paid counsel, and the courts, would be grossly

burdened in the interest of providing representation at proceedings in which the

possibility of finding constitutional error is, in our experience, highly remote. If

Congress wishes to furnish counsel to state prisoners to enable them to discover

if they have been deprived of constitutional rights, that is a legislative matter.

We do not consider it a judicial obligation when a prisoner does nothing more

than make unsupported conclusory allegations.

4

We will not appoint counsel for petitioner, but we will look beyond his

inadequate petition to his accompanying detailed memorandum of fact and law.

Accepting those factual allegations as true for present purposes, petitioner

asserts error in a series of routine trial rulings. These he seeks to convert into

the needed constitutional claim by saying that they deprived him of a "fair

trial." We recognize no such easy device. We might consider many state

decisions "unfair" in the sense that we would have decided the other way. Far

more than this is needed to make constitutional error. Gryger v. Burke, 1948,

334 U.S. 728, 731, 68 S.Ct. 1256, 92 L.Ed. 1683; Buchalter v. New York,

1943, 319 U.S. 427, 429-430, 63 S.Ct. 1129, 87 L.Ed. 1492; cf. Snowden v.

Hughes, 1944, 321 U.S. 1, 10-11, 64 S.Ct. 397, 88 L.Ed. 497.

In the case at bar we not only perceive no constitutional error as such, but in

passing we observe that we are not led to believe that error of any sort

occurred. Petitioner was not entitled to cross-examine a government witness on

a "trial run" basis in the absence of the jury. Nor was he wronged when the

court charged the jury that the government's burden need not go beyond a

reasonable doubt into mere flights of possibilities. Finally, if the court admitted

hearsay evidence, or other incompetent testimony, petitioner has not

sufficiently shown it.

The certificate of probable cause and defendant's request for other relief are

denied.

You might also like

- An Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeFrom EverandAn Inexplicable Deception: A State Corruption of JusticeNo ratings yet

- James J. Connor v. Philip J. Picard, 434 F.2d 673, 1st Cir. (1970)Document6 pagesJames J. Connor v. Philip J. Picard, 434 F.2d 673, 1st Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Keith Gayle v. Eugene Lefevre, Superintendent, Clinton Correctional Facility, 613 F.2d 21, 2d Cir. (1980)Document13 pagesKeith Gayle v. Eugene Lefevre, Superintendent, Clinton Correctional Facility, 613 F.2d 21, 2d Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Henry P. Arsenault, Jr. v. John A. Gavin, Warden or Principal Officer, Massachusetts Correctional Institution, 248 F.2d 777, 1st Cir. (1957)Document5 pagesHenry P. Arsenault, Jr. v. John A. Gavin, Warden or Principal Officer, Massachusetts Correctional Institution, 248 F.2d 777, 1st Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Buchanan v. O'Brien, 181 F.2d 601, 1st Cir. (1950)Document8 pagesBuchanan v. O'Brien, 181 F.2d 601, 1st Cir. (1950)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joseph Subilosky v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 412 F.2d 691, 1st Cir. (1969)Document4 pagesJoseph Subilosky v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 412 F.2d 691, 1st Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Charles R. Luse v. United States, 326 F.2d 338, 10th Cir. (1964)Document4 pagesCharles R. Luse v. United States, 326 F.2d 338, 10th Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- James J. Domenica v. United States, 292 F.2d 483, 1st Cir. (1961)Document4 pagesJames J. Domenica v. United States, 292 F.2d 483, 1st Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America Ex Rel. Edwin W. Gockley v. David N. Myers, Superintendent, State Correctional Institution, Graterford, Pennsylvania, 378 F.2d 398, 3rd Cir. (1967)Document4 pagesUnited States of America Ex Rel. Edwin W. Gockley v. David N. Myers, Superintendent, State Correctional Institution, Graterford, Pennsylvania, 378 F.2d 398, 3rd Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bourdon v. State, Alaska Ct. App. (2016)Document5 pagesBourdon v. State, Alaska Ct. App. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rubin F. Needel v. Palmer C. Scafati, Superintendent, 412 F.2d 761, 1st Cir. (1969)Document7 pagesRubin F. Needel v. Palmer C. Scafati, Superintendent, 412 F.2d 761, 1st Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- James Elmore Puckett v. United States, 314 F.2d 298, 10th Cir. (1963)Document5 pagesJames Elmore Puckett v. United States, 314 F.2d 298, 10th Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Victor C. Bynoe, 562 F.2d 126, 1st Cir. (1977)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Victor C. Bynoe, 562 F.2d 126, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America Ex Rel. Alfred Schnitzler v. Hon. Harold W. Follette, Warden of Green Haven Prison, Stormville, New York, 406 F.2d 319, 2d Cir. (1969)Document5 pagesUnited States of America Ex Rel. Alfred Schnitzler v. Hon. Harold W. Follette, Warden of Green Haven Prison, Stormville, New York, 406 F.2d 319, 2d Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Arthur O. Cacchillo, 416 F.2d 231, 2d Cir. (1969)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Arthur O. Cacchillo, 416 F.2d 231, 2d Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Anthony G. Forgione, 487 F.2d 364, 1st Cir. (1974)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Anthony G. Forgione, 487 F.2d 364, 1st Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States of America Ex Rel. Ernest J. Bolognese E-9803 v. Joseph R. Brierley, Superintendent, 412 F.2d 193, 3rd Cir. (1969)Document9 pagesUnited States of America Ex Rel. Ernest J. Bolognese E-9803 v. Joseph R. Brierley, Superintendent, 412 F.2d 193, 3rd Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Reginald Jells v. Ohio, 498 U.S. 1111 (1991)Document6 pagesReginald Jells v. Ohio, 498 U.S. 1111 (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- X v. United States, 454 F.2d 255, 2d Cir. (1971)Document8 pagesX v. United States, 454 F.2d 255, 2d Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Donald F. Bettenhausen and Bernice A. Bettenhausen, 499 F.2d 1223, 10th Cir. (1974)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Donald F. Bettenhausen and Bernice A. Bettenhausen, 499 F.2d 1223, 10th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Richard M. Penta, 475 F.2d 92, 1st Cir. (1973)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Richard M. Penta, 475 F.2d 92, 1st Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In Re Grand Jury Investigation, Philip Charles Testa, Witness. Appeal of Philip Charles Testa, 486 F.2d 1013, 3rd Cir. (1973)Document7 pagesIn Re Grand Jury Investigation, Philip Charles Testa, Witness. Appeal of Philip Charles Testa, 486 F.2d 1013, 3rd Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963)Document23 pagesSanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Francis A. Vitello v. Charles Gaughan, Etc., 544 F.2d 17, 1st Cir. (1976)Document3 pagesFrancis A. Vitello v. Charles Gaughan, Etc., 544 F.2d 17, 1st Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- James J. Stokes v. Michael E. Fair, 581 F.2d 287, 1st Cir. (1978)Document5 pagesJames J. Stokes v. Michael E. Fair, 581 F.2d 287, 1st Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harris v. Nelson, 394 U.S. 286 (1969)Document16 pagesHarris v. Nelson, 394 U.S. 286 (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- David B. Powers v. United States, 325 F.2d 666, 1st Cir. (1963)Document2 pagesDavid B. Powers v. United States, 325 F.2d 666, 1st Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Booker T. Shephard v. Ron Champion, Warden, Attorney General, For The State of Oklahoma, 936 F.2d 583, 10th Cir. (1991)Document6 pagesBooker T. Shephard v. Ron Champion, Warden, Attorney General, For The State of Oklahoma, 936 F.2d 583, 10th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nollie Lee Martin v. Richard L. Dugger, Secretary, Florida Department of Corrections, 891 F.2d 807, 11th Cir. (1989)Document6 pagesNollie Lee Martin v. Richard L. Dugger, Secretary, Florida Department of Corrections, 891 F.2d 807, 11th Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Alan Lloyd Lussier v. Frank O. Gunter, 552 F.2d 385, 1st Cir. (1977)Document6 pagesAlan Lloyd Lussier v. Frank O. Gunter, 552 F.2d 385, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Perez v. Ledesma, 401 U.S. 82 (1971)Document41 pagesPerez v. Ledesma, 401 U.S. 82 (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gutianez v. Parker, 10th Cir. (2007)Document8 pagesGutianez v. Parker, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Florencio Merced Rosa, Etc. v. Blas C. Herrero, JR., Etc., 423 F.2d 591, 1st Cir. (1970)Document4 pagesFlorencio Merced Rosa, Etc. v. Blas C. Herrero, JR., Etc., 423 F.2d 591, 1st Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- John Suggs v. J. Edwin Lavallee, Superintendent, Clinton State Correctional Institution, 570 F.2d 1092, 2d Cir. (1978)Document43 pagesJohn Suggs v. J. Edwin Lavallee, Superintendent, Clinton State Correctional Institution, 570 F.2d 1092, 2d Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Paul C. Porter, 807 F.2d 21, 1st Cir. (1986)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Paul C. Porter, 807 F.2d 21, 1st Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brad S. Beightol, A Minor, by His Guardian, Arlene L. Beightol v. Joseph Kunowski, 486 F.2d 293, 3rd Cir. (1973)Document3 pagesBrad S. Beightol, A Minor, by His Guardian, Arlene L. Beightol v. Joseph Kunowski, 486 F.2d 293, 3rd Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Homer Bush v. The United States Postal Service, 496 F.2d 42, 4th Cir. (1974)Document4 pagesHomer Bush v. The United States Postal Service, 496 F.2d 42, 4th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 1071762Document29 pages1071762SuryanshNo ratings yet

- Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965)Document26 pagesLinkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Bowen v. Johnston, 306 U.S. 19 (1939)Document8 pagesBowen v. Johnston, 306 U.S. 19 (1939)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Efrid Brown and William J. Johnson, Jr. v. Frank O. Gunter, Etc., 562 F.2d 122, 1st Cir. (1977)Document5 pagesEfrid Brown and William J. Johnson, Jr. v. Frank O. Gunter, Etc., 562 F.2d 122, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joseph Lussier, 929 F.2d 25, 1st Cir. (1991)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Joseph Lussier, 929 F.2d 25, 1st Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The United States of America v. Emanuel Lester, 247 F.2d 496, 2d Cir. (1957)Document9 pagesThe United States of America v. Emanuel Lester, 247 F.2d 496, 2d Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Pauline Caldwell Appeal of Audrey Brickley, 463 F.2d 590, 3rd Cir. (1972)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Pauline Caldwell Appeal of Audrey Brickley, 463 F.2d 590, 3rd Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Murphy v. Waterfront Comm'n of NY Harbor, 378 U.S. 52 (1964)Document42 pagesMurphy v. Waterfront Comm'n of NY Harbor, 378 U.S. 52 (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Francis T. Glynn v. Robert Donnelly, John M. Farrell v. Robert Donnelly, 470 F.2d 95, 1st Cir. (1972)Document6 pagesFrancis T. Glynn v. Robert Donnelly, John M. Farrell v. Robert Donnelly, 470 F.2d 95, 1st Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965)Document17 pagesDombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Robert Bialkin, 331 F.2d 956, 2d Cir. (1964)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Robert Bialkin, 331 F.2d 956, 2d Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Barry Gibbs v. Frederick K. Frank District Attorney of Pike County Attorney General of Pennsylvania, 387 F.3d 268, 3rd Cir. (2004)Document13 pagesBarry Gibbs v. Frederick K. Frank District Attorney of Pike County Attorney General of Pennsylvania, 387 F.3d 268, 3rd Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lloyd G. Ellis v. State of Maine, 448 F.2d 1325, 1st Cir. (1971)Document3 pagesLloyd G. Ellis v. State of Maine, 448 F.2d 1325, 1st Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dante Edward Gori, 282 F.2d 43, 2d Cir. (1960)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Dante Edward Gori, 282 F.2d 43, 2d Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Walter J. Harlan, 696 F.2d 5, 1st Cir. (1983)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Walter J. Harlan, 696 F.2d 5, 1st Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tacon v. Arizona, 410 U.S. 351 (1973)Document4 pagesTacon v. Arizona, 410 U.S. 351 (1973)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Francis O'HallOran v. Joseph Ryan, Superintendent, The Attorney General of The State of Pennsylvania, District Attorney For Lehigh County, 835 F.2d 506, 3rd Cir. (1987)Document6 pagesFrancis O'HallOran v. Joseph Ryan, Superintendent, The Attorney General of The State of Pennsylvania, District Attorney For Lehigh County, 835 F.2d 506, 3rd Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Glen Grayson, by His Next of Friend John Grayson v. Kessler Montgomery, 421 F.2d 1306, 1st Cir. (1970)Document6 pagesGlen Grayson, by His Next of Friend John Grayson v. Kessler Montgomery, 421 F.2d 1306, 1st Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Calvin W. Pruitt v. C. C. Peyton, Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 338 F.2d 859, 4th Cir. (1964)Document4 pagesCalvin W. Pruitt v. C. C. Peyton, Superintendent of The Virginia State Penitentiary, 338 F.2d 859, 4th Cir. (1964)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument7 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Robert H. Mottram v. Frank F. Murch, 458 F.2d 626, 1st Cir. (1972)Document6 pagesRobert H. Mottram v. Frank F. Murch, 458 F.2d 626, 1st Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ruel Hux, Jr. v. A.I. Murphy, Warden and The State of Oklahoma, 733 F.2d 737, 10th Cir. (1984)Document5 pagesRuel Hux, Jr. v. A.I. Murphy, Warden and The State of Oklahoma, 733 F.2d 737, 10th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Myron Crisdon v. New Jersey Department of Educa, 3rd Cir. (2012)Document4 pagesMyron Crisdon v. New Jersey Department of Educa, 3rd Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cojuangco v. VillegasDocument3 pagesCojuangco v. VillegasSocrates Jerome De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Petition To Connecticut Supreme CourtDocument9 pagesPetition To Connecticut Supreme CourtJosephine MillerNo ratings yet

- California Code of Civil Procedure Section 170.4 Striking 170.3Document1 pageCalifornia Code of Civil Procedure Section 170.4 Striking 170.3JudgebustersNo ratings yet

- 57 Gigantoni V PeopleDocument3 pages57 Gigantoni V PeopleDarrell MagsambolNo ratings yet

- Ashcroft V IqbalDocument3 pagesAshcroft V IqbalMỹ Anh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Vakalatnama Dept - English EmptyDocument1 pageVakalatnama Dept - English EmptyRajdeep Singh ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Kentucky PTA v. JCPS, JCBE and Gay AdelmannDocument6 pagesKentucky PTA v. JCPS, JCBE and Gay AdelmannCourier JournalNo ratings yet

- (PC) Denning v. Reynolds Et Al - Document No. 4Document2 pages(PC) Denning v. Reynolds Et Al - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court G.R. No. L-18289 March 31, 1964 Andres Romero, Maiden Form Brassiere Co., Inc., and The Director of PatentsDocument2 pagesSupreme Court G.R. No. L-18289 March 31, 1964 Andres Romero, Maiden Form Brassiere Co., Inc., and The Director of Patentsmystery law manNo ratings yet

- (PC) Hall v. Pliler Et Al - Document No. 3Document2 pages(PC) Hall v. Pliler Et Al - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Hill v. Vanderbilt Capital Advisors, 10th Cir. (2012)Document14 pagesHill v. Vanderbilt Capital Advisors, 10th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Government of The Virgin Islands v. Albion William Bodle, 427 F.2d 532, 3rd Cir. (1970)Document3 pagesGovernment of The Virgin Islands v. Albion William Bodle, 427 F.2d 532, 3rd Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kevin Maurice Smith, 4th Cir. (2000)Document3 pagesUnited States v. Kevin Maurice Smith, 4th Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ancillary Claim FormDocument3 pagesAncillary Claim FormDalleh WashingtonNo ratings yet

- Notes On Pretrial Brief and Judicial AffidavitDocument16 pagesNotes On Pretrial Brief and Judicial AffidavitJamellen De Leon BenguetNo ratings yet

- L.A. (Jack) Thomasson v. Jules J. Modlinski, Individually and in His Official Capacity as Executive Director of Southside Community Services Board Edward Owens, Individually and in His Official Capacity as Chairman of the Board of Southside Community Services Board Southside Community Services Board Mecklenburg County, Virginia Brunswick County, Virginia Halifax County, Virginia City of South Boston, Virginia, and Bennett Nelson, Individually and in His Official Capacity as Human Resource Manager to Community Service Boards With the Virginia Department of Mental Health, Mental Retardation and Substance Abuse, 76 F.3d 375, 4th Cir. (1996)Document7 pagesL.A. (Jack) Thomasson v. Jules J. Modlinski, Individually and in His Official Capacity as Executive Director of Southside Community Services Board Edward Owens, Individually and in His Official Capacity as Chairman of the Board of Southside Community Services Board Southside Community Services Board Mecklenburg County, Virginia Brunswick County, Virginia Halifax County, Virginia City of South Boston, Virginia, and Bennett Nelson, Individually and in His Official Capacity as Human Resource Manager to Community Service Boards With the Virginia Department of Mental Health, Mental Retardation and Substance Abuse, 76 F.3d 375, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Atty. Funtila Abugan-SYLLABUS - SuccessionDocument4 pagesAtty. Funtila Abugan-SYLLABUS - SuccessionSean ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Case 30 Fluemer V HixDocument2 pagesCase 30 Fluemer V HixJames GaddaoNo ratings yet

- International Courts BrochureDocument2 pagesInternational Courts Brochurekrys_elleNo ratings yet

- Metro Bank & Trust Company vs. MirandaDocument1 pageMetro Bank & Trust Company vs. MirandaBenjo Romil NonoNo ratings yet

- California v. Texas - 593 U.S. - (2021) - Justia US Supreme Court CenterDocument5 pagesCalifornia v. Texas - 593 U.S. - (2021) - Justia US Supreme Court CenterRegine GumbocNo ratings yet

- Redfield v. Parks, 130 U.S. 623 (1889)Document2 pagesRedfield v. Parks, 130 U.S. 623 (1889)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 3) PP Vs CawiliDocument1 page3) PP Vs CawiliAlexis Capuras EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Letter and Motion To WithdrawDocument3 pagesLetter and Motion To WithdrawDarwin ViadumangNo ratings yet

- Judicial Precedent: Key Fact ChartsDocument6 pagesJudicial Precedent: Key Fact ChartsFarhan Khan100% (1)

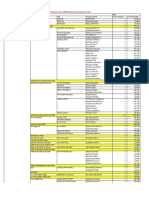

- NY State Payroll Southern Tier StudyDocument285 pagesNY State Payroll Southern Tier StudylaxdesignNo ratings yet

- Virtuoso v. Municipal Judge Case DigestDocument1 pageVirtuoso v. Municipal Judge Case DigestKristian Dave BedionesNo ratings yet

- Manuel JusayanDocument2 pagesManuel JusayanjamesNo ratings yet

- 85 Tolentino V Paras, G.R. No. L-43905 May 30, 1983 (122 SCRA 525)Document2 pages85 Tolentino V Paras, G.R. No. L-43905 May 30, 1983 (122 SCRA 525)Lester AgoncilloNo ratings yet

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionFrom EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2475)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismFrom EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearFrom EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (560)

- Maktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistFrom EverandMaktub: An Inspirational Companion to The AlchemistRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Summary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeFrom EverandSummary of Dan Martell's Buy Back Your TimeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryFrom EverandThe Mountain is You: Transforming Self-Sabotage Into Self-MasteryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (882)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfFrom EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1459)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesFrom EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1635)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Master Your Emotions: Develop Emotional Intelligence and Discover the Essential Rules of When and How to Control Your FeelingsFrom EverandMaster Your Emotions: Develop Emotional Intelligence and Discover the Essential Rules of When and How to Control Your FeelingsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (321)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelFrom EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentFrom EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4125)

- Bedtime Stories for Stressed Adults: Sleep Meditation Stories to Melt Stress and Fall Asleep Fast Every NightFrom EverandBedtime Stories for Stressed Adults: Sleep Meditation Stories to Melt Stress and Fall Asleep Fast Every NightRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (124)

- Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeFrom EverandEat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3226)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonFrom EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1481)