Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In The Matter of Denis Edward Bowyer, Debtor. NCNB Texas National Bank, Formerly First Republicbank Austin v. Denis Edward Bowyer, 916 F.2d 1056, 1st Cir. (1990)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

In The Matter of Denis Edward Bowyer, Debtor. NCNB Texas National Bank, Formerly First Republicbank Austin v. Denis Edward Bowyer, 916 F.2d 1056, 1st Cir. (1990)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

916 F.

2d 1056

59 USLW 2386, 24 Collier Bankr.Cas.2d 238,

Bankr. L. Rep. P 73,676

In the Matter of Denis Edward BOWYER, Debtor.

NCNB TEXAS NATIONAL BANK, formerly First

Republicbank

Austin, Appellant,

v.

Denis Edward BOWYER, Appellee.

No. 89-7029.

United States Court of Appeals,

Fifth Circuit.

Nov. 14, 1990.

Joanalys B. Smith, Thomas T. Rogers, Small, Craig & Werkenthin,

Austin, Tex., for appellant.

William C. Davidson, Jr., Austin, Tex., for appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of

Texas.

Before WISDOM, DAVIS, and BARKSDALE, Circuit Judges.

BARKSDALE, Circuit Judge:

I.

Appellant NCNB objected to Dr. Bowyer's discharge in his Chapter 7

bankruptcy proceeding; but, the bankruptcy court allowed it, and the district

court affirmed. Because Bowyer's use of non-exempt funds on the eve of

bankruptcy, including conversion to exempt assets (such as satisfaction of his

homestead mortgage), constituted intent to hinder or delay a creditor, we

REVERSE.

Bowyer, an anesthesiologist, was a member of Capitol Anesthesiology

Association (CAA), a professional corporation. In 1985 and in 1986, his yearly

income was $230,000. He testified that expenses exceeded income by

approximately $2,000 each month, but that he and his family had a modest

lifestyle.1

In 1983, Bowyer purchased 12 condominiums with a loan from a predecessor

of NCNB (the Bank), in the amount of $560,000.2 In 1986, the Bank consented

to the sale of one of the condominiums, which netted only 50 cents on the

dollar. In March 1987, Bowyer sold the remaining condominiums at a similarly

depressed price, which was less than the outstanding mortgage. The Bank

refinanced the entire $342,645.91 deficiency, with Bowyer required to

contribute only the net sale proceeds for the refinancing.

The Bank's loan officer testified that the refinancing was based on Bowyer's

May 1986 financial statement. The detailed assets included gold Mapleleafs

valued at $12,000 and $42,000 in "Cash on Hand and in Banks."3 Bowyer

maintained depository accounts, including a money market fund, with the

Bank. He told the Bank that he intended to, and did, maintain at least two

quarters worth of loan payments in the money market account; and it contained

approximately $41,000 on the date of the 1986 statement. Bowyer's April 1987

financial statement for the Bank listed, among other assets, $60,000 on deposit

in the Bank and valued the Mapleleafs at $18,000. In signing the financial

statements, Bowyer agreed to inform the bank of any material change in his

financial condition.

After the refinancing, Bowyer made monthly payments of $5,585 to the Bank

until he filed for bankruptcy in October 1987. In June and July 1987, he also

made unscheduled payments to the Bank, reducing the principal by $25,000.

At the time of the refinancing in the spring of 1987, Bowyer was aware of

changes in his anesthesiology practice which would decrease his income. In

July 1987, he sold the Mapleleafs for approximately $18,000. He did not

deposit the proceeds in a bank; instead, his wife carried them in her purse.4

Moreover, he did not inform the Bank of this change in his listed assets.

Bowyer spent some of the gold proceeds on travel, including $6,000 to send his

wife and three friends to Hawaii. He also used the proceeds to purchase

clothing and furniture and housewares for his homestead. That summer,

Bowyer also spent an additional $7,000, not part of the gold proceeds, on

homestead improvements, including adding a greenhouse.

On September 28, 1987, at Bowyer's professional corporation's (CAA's) retreat,

CAA's tax attorney informed him of tax code changes which would decrease

his income. Bowyer testified that he then realized that he "might have to go into

some sort of bankruptcy." Bowyer met with CAA's tax attorney and a

bankruptcy attorney in early October; he paid a retainer to the bankruptcy

attorney.

Bowyer's wife withdrew $24,002 from their money market account with the

Bank on October 13, 1987. The withdrawal was used to purchase a $24,000

cashiers check, payable to Bowyer's wife, which she endorsed and used to

satisfy their homestead mortgage at another bank. Bowyer testified that he did

this "to cut down monthly payments"; there had been no demand for payment

in full. And, in mid-October, Bowyer spent approximately $4,000 to attend

parents' weekend at his daughter's school.

10

Bowyer filed a Chapter 7 petition on October 28, 1987. The Bank instituted an

adversary proceeding, objecting to Bowyer's discharge. The bankruptcy court

allowed the discharge, and the district court adopted the bankruptcy court's

findings and affirmed.

II.

11

Among other assets for which Bowyer could claim an exemption in his Chapter

7 bankruptcy proceeding were those protected by the liberal Texas homestead

law. 11 U.S.C. Sec. 522; Tex. Const. art. XVI Sec. 50; see Matter of Reed, 700

F.2d 986, 989-91 (5th Cir.1983). Bowyer's improvements to, and purchases for,

his homestead in the summer of 1987 and the satisfaction of his homestead

mortgage that fall constituted conversion of bankruptcy non-exempt to exempt

assets.

12

At issue is whether Bowyer's use of non-exempt funds, including converting

them to such exempt assets, precludes his discharge. Such use, without more,

does not. To determine discharge vel non, we look to Bankruptcy Code Sec.

727, which provides in part:

13 The court shall grant the debtor a discharge, unless ... (2) the debtor, with intent

(a)

to hinder, delay, or defraud a creditor, ... has transferred, removed, ... (A) property of

the debtor, within one year before the date of the filing of the petition.

14

11 U.S.C. Sec. 727(a)(2)(A). Bowyer transferred and removed certain of his

property within one year of filing; he used the money market proceeds to pay

off his homestead mortgage, and spent the gold proceeds and other sizeable

sums on homestead improvements and items, on travel, and on nonrecoverable

expenses. Matter of Smiley, 864 F.2d 562, 565 (7th Cir.1989) (transfer is any

disposition of a property interest); 11 U.S.C. Sec. 101(50). Accordingly, we

turn to whether he did so "with intent to hinder, delay or defraud a creditor." 11

U.S.C. Sec. 727(a)(2)(A) (emphasis added).

15

The bankruptcy court found that "there seems to be intent to place assets

beyond the reach of creditors, this intent goes to pre-bankruptcy planning, not

an intent to defraud." (Emphasis added.) That court also found that Bowyer's

actions were not a "concerted scheme", as found in Reed, discussed below. The

Bank contends that pursuant to Sec. 727(a)(2)(A), Bowyer should not have

been discharged; that the bankruptcy and district courts erred in finding that

Bowyer did not transfer property with intent to hinder, delay, or defraud a

creditor.

16

Conclusions of law are subject to plenary review. Matter of Multiponics, Inc.,

622 F.2d 709, 713 (5th Cir.1980). On the other hand, "[t]he fact findings of the

bankruptcy judge, affirmed by the district court, are to be credited by [the

reviewing court] unless clearly erroneous." Reed, 700 F.2d at 992. A finding of

fact is clearly erroneous "when although there is evidence to support it, the

reviewing court on the entire evidence is left with a firm and definite

conviction that a mistake has been committed." United States v. United States

Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395, 68 S.Ct. 525, 542, 92 L.Ed. 746 (1948).

Pursuant to our review of the record, we are left with such a conviction; while

there may not have been intent to defraud, there was intent to hinder or delay.

A.

17

"[M]ere conversion [of non-exempt assets] is not to be considered fraudulent

[under Sec. 727(a)(2)(A) ] unless other evidence proves actual intent to defraud

creditors." Reed, 700 F.2d at 991 (emphasis added). And, a court may infer

such actual intent from the circumstances of the debtor's conduct. Smiley, 864

F.2d at 566. See Reed, 700 F.2d at 991. In Reed, the debtor's whole pattern of

conduct evinced an actual intent to defraud. The debtor had been unable to meet

his obligations for the prior year; and a consultant was managing his business,

based upon an agreement with his creditors, by which they postponed

collection efforts. Nonetheless, the debtor diverted business receipts into a

secret account and used this money to obtain loans, which he used to pay off his

homestead. He also sold his antique and other collections for less than their

cost and was unable to account for approximately $20,000 in cash. Id. at 98889.

18

The bankruptcy court's finding, affirmed by the district court, that Bowyer did

not have an actual intent to defraud is not clearly erroneous.5 For example, on

the eve of bankruptcy, he did not borrow money that was then converted into

exempt assets, Reed, 700 F.2d at 991, nor did the evidence reveal any extrinsic

acts of fraud. Smiley, 864 F.2d at 567. His failure to list his liabilities or inform

the Bank of changes in his financial condition do not necessarily render his

subsequent acts fraudulent; a "finding of fraud requires more than a failure to

volunteer information." Smiley, 864 F.2d at 568 (citing Continental Bank &

Trust Co. v. Winter, 153 F.2d 397 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 329 U.S. 717, 67 S.Ct.

49, 91 L.Ed. 622 (1946)).

B.

19

As stated, while Bowyer's intent does not appear to reach the level of actual

fraud, we do find intent to hinder or delay a creditor. E.g., Smiley, 864 F.2d at

568. The bankruptcy and district courts did not rule expressly on whether there

was intent to hinder or delay. The bankruptcy court limited its holding, finding

only that Bowyer's actions were not "the intent to defraud that the statute

contemplates"; and the district court did not address this issue. (Emphasis

added.) 6

20

However, the term "defraud" does not subsume "hinder or delay." E.g., see

Smiley, 864 F.2d at 568; Norwest Bank Nebraska, N.A. v. Tveten, 848 F.2d

871, 878 (8th Cir.1988) (dissent). Pursuant to well established rules of statutory

construction, "unless otherwise defined, words will be interpreted as taking

their ordinary, contemporary, common meaning." Perrin v. U.S., 444 U.S. 37,

42, 100 S.Ct. 311, 314, 62 L.Ed.2d 199 (1979); Bruce v. First Fed. Savings and

Loan Ass'n, 837 F.2d 712, 714 (5th Cir.1988). Furthermore, such rules require

that we interpret a statute "to give effect, if possible, to every word Congress

used." Boureslan v. Aramco, Arabian American Oil Co., 892 F.2d 1271, 1275

(5th Cir.1990) (dissent), cert. granted, --- U.S. ----, 111 S.Ct. 40, 112 L.Ed.2d

17 (1990) (quoting Reiter v. Sonotone Corp., 442 U.S. 330, 339, 99 S.Ct. 2326,

2331, 60 L.Ed.2d 931 (1979)).

21

There is little legislative or judicial guidance on how to determine what actions

fall within "intent" either to "hinder" or to "delay," especially concerning the

conversion of non-exempt to exempt assets on the eve of bankruptcy. E.g., see

Smiley, 864 F.2d at 566-67; Norwest Bank, 848 F.2d at 873-79; Reed, 700 F.2d

at 990-91. Nevertheless, Bowyer's activities appear to be the very actions

covered by either, or both, terms. One approach that appears appropriate in this

instance is the "pig to hog" analysis: "when a pig becomes a hog it is

slaughtered." See, e.g., Norwest Bank, 848 F.2d at 879 (quoting In Re Zouhar,

10 B.R. 154, 157 (Bktcy.D.N.M.1981)). This analysis recognizes that while

some pre-bankruptcy planning is appropriate, the wholesale expenditure of

non-exempt assets on the eve of bankruptcy, including conversion to exempt

assets (especially where there are liberal state law exemptions), may not be.

22

Bowyer's actions can be argued to be allowable pre-bankruptcy planning; but

this argument fails in light of his spending spree and the separate satisfaction of

his homestead mortgage. For example, despite his avowed modest lifestyle,

Bowyer spent the $18,000 from the gold sale on non-recoverable travel and

exempt assets, during a period of time when he was both heavily indebted to the

Bank and knew that he had financial troubles. But especially critical to finding

extrinsic evidence of an intent to hinder or delay is that these funds were not

deposited with a banking institution--certainly not his money market account

with the Bank--rather, his wife carried the proceeds in her purse. As another

example, in addition to other substantial homestead improvements in the

summer of 1987, such as installing central air conditioning and heating, he

added a greenhouse. And as a final example, he voluntarily satisfied his

homestead mortgage 15 days before filing for bankruptcy, after discussing

bankruptcy with two lawyers. His method of doing so, starting with the

cashier's check payable to his wife, as described above, speaks volumes about

Bowyer's intent to hinder or delay the Bank. In doing so, Bowyer took

advantage of Texas' more than generous homestead law, which "provides an

incentive for debtors such as ... [Bowyer] to keep their creditors in the dark

about their conversion activities." Smiley, 864 F.2d at 568.

23

In sum, Bowyer's actions go beyond allowable pre-bankruptcy planning and are

extrinsic evidence of an intent to hinder and delay a creditor, even though he

may not have had an intent to defraud them. Smiley, 864 F.2d at 568; In re

Adeeb, 787 F.2d 1339, 1343 (9th Cir.1986) (citing In re Trinity Baptist Church,

Inc., 25 B.R. 529, 532-33 (Bankr.M.D.Fla.1982)). Therefore, the district court

erred in granting Bowyer a discharge under Sec. 727.7

III.

24

Finding that the district court erred in affirming the bankruptcy court's order

allowing Bowyer's discharge, we

25

REVERSE and REMAND for proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Bowyer's monthly expenses included approximately $1,200 for his daughter's

private school and $800 for recreation

2

The lending Bank was Interfirst Bank Austin; First RepublicBank purchased

Interfirst; and NCNB purchased First RepublicBank

The statement listed his interest in a limited partnership as $60,000, but failed to

state that this amount was pledged as collateral on another bank loan. Bowyer

also failed to list a general partnership debt of $300,000. His contingent

liabilities roughly equaled his net worth

As stated, he had a money market account with the Bank; and it was listed on

his 1986 and 1987 financial statements given the Bank, as were the Mapleleafs

The Bank contends also that the discharge must be denied because the

bankruptcy court stated that "[o]n its face, all the elements of Reed appear

satisfied." However, this statement must be considered in context: the

bankruptcy court completed the statement by concluding that Bowyer's intent

was "not an intent to defraud"; and that therefore, it would be inappropriate to

deny his discharge

The bankruptcy court may have included hinder or delay within that finding by

implication. But, in any event, because this is a mixed question of law and fact,

we reach it here, rather than remand for further findings

Because we reverse on this issue, we need not reach the Bank's other

contentions: that Bowyer (1) fraudulently or knowingly made false oath or

account, under 11 U.S.C. Sec. 727(a)(4); (2) did not satisfactorily explain the

dissipation of assets, under 11 U.S.C. Sec. 727(a)(5); made a false statement in

writing, under 11 U.S.C. Sec. 523(a)(2)(B); and obtained refinancing by actual

fraud or misrepresentation, under 11 U.S.C. Sec. 523(a)(2)(A)

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Allocating Unauthorised Credit Card Payment Losses: The Credit Card Guidelines and Consumer ProtectionDocument14 pagesAllocating Unauthorised Credit Card Payment Losses: The Credit Card Guidelines and Consumer ProtectionHobart Zi Ying LimNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Detect red flags of fraud and schemes in documentsDocument40 pagesDetect red flags of fraud and schemes in documentsjit21senNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Canadian EditionDocument50 pagesIntroduction to Canadian EditionJeffrey King100% (2)

- Your Adv Safebalance Banking: Account SummaryDocument10 pagesYour Adv Safebalance Banking: Account SummaryLaura Del valleNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Application To Open An Account: Individual Tier IiiDocument11 pagesApplication To Open An Account: Individual Tier IiiUche Maxwell TivolyNo ratings yet

- LAB# 08: Inheritance: DescriptionDocument5 pagesLAB# 08: Inheritance: DescriptionMuhammad Hamza AminNo ratings yet

- Commercefactory - in-UGPG PROJECTS Commerce Factory PDFDocument6 pagesCommercefactory - in-UGPG PROJECTS Commerce Factory PDFManoj Kumar GeldaNo ratings yet

- Vision VAM 2020 (Governance) Development ProcessDocument41 pagesVision VAM 2020 (Governance) Development ProcessShivamNo ratings yet

- Recruitment and Selection Process of Southeast Bank LimitedDocument23 pagesRecruitment and Selection Process of Southeast Bank LimitedRuhul Amin Rahat0% (1)

- ICAAP Sllovenia GuidelineDocument44 pagesICAAP Sllovenia GuidelineDritaNo ratings yet

- Company's Profile Presentation (Mauritius Commercial Bank)Document23 pagesCompany's Profile Presentation (Mauritius Commercial Bank)ashairways100% (2)

- IDBI PresentationDocument13 pagesIDBI PresentationDP DileepkumarNo ratings yet

- Gani Hartanto M Comm.: ExperienceDocument6 pagesGani Hartanto M Comm.: ExperienceGreen Sustain EnergyNo ratings yet

- Attached To and Forming Part of Policy No. 4011/C/00000000000/01/000Document19 pagesAttached To and Forming Part of Policy No. 4011/C/00000000000/01/000Utsav J BhattNo ratings yet

- Summer Project On Real Est. Page .1Document55 pagesSummer Project On Real Est. Page .1manisha_s200774% (19)

- International Project Finance: Review and Implications For International Finance and International BusinessDocument37 pagesInternational Project Finance: Review and Implications For International Finance and International BusinessSuraj PatelNo ratings yet

- Functions of IfciDocument4 pagesFunctions of IfciKŕiśhñą Śińgh100% (1)

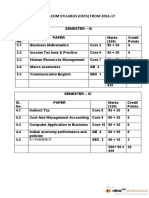

- Syllabus 3Sem.-6Sem.Document33 pagesSyllabus 3Sem.-6Sem.Smart Earn 2020 ONLINENo ratings yet

- 2016 17 EDITABLE Matched Funding Grant Application FormDocument6 pages2016 17 EDITABLE Matched Funding Grant Application FormeddyNo ratings yet

- Proof of Cash (AutoRecovered)Document4 pagesProof of Cash (AutoRecovered)Portia SupedaNo ratings yet

- Tybbi ProjectDocument80 pagesTybbi ProjectSagar KhillareNo ratings yet

- 228 Zander Marz Beyond The Government Haunted World PDFDocument196 pages228 Zander Marz Beyond The Government Haunted World PDFMatthew Buechler100% (1)

- UNDP Internal Control GuideDocument61 pagesUNDP Internal Control GuideRaufi MatinNo ratings yet

- Bank RateDocument4 pagesBank RateAnonymous Ne9hTRNo ratings yet

- BNK 601Document5 pagesBNK 601Háłīmà TáríqNo ratings yet

- Corporate Accounting Multiple Choice QuestionsDocument23 pagesCorporate Accounting Multiple Choice QuestionsحسينبيسواسNo ratings yet

- Risk Analysis For Financial Engineering SEEM3580: Lecture1: Risks of Financial InstitutionsDocument52 pagesRisk Analysis For Financial Engineering SEEM3580: Lecture1: Risks of Financial InstitutionsChan Tsz HinNo ratings yet

- Finacle commands for term depositsDocument1 pageFinacle commands for term depositshiss laNo ratings yet

- HR Practices in Bank Alfalah LimitedDocument42 pagesHR Practices in Bank Alfalah LimitedRaheel Mahmood Qureshi50% (10)

- Charity Care SectionDocument36 pagesCharity Care SectionRehan SadiqNo ratings yet