Professional Documents

Culture Documents

La Semejanza Desde El Punto de Vista de Deleuze

Uploaded by

Juan Pablo Anaya0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views2 pagesfragmento del libro "Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy" por Manuel Delanda

Original Title

La semejanza desde el punto de vista de Deleuze

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentfragmento del libro "Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy" por Manuel Delanda

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views2 pagesLa Semejanza Desde El Punto de Vista de Deleuze

Uploaded by

Juan Pablo Anayafragmento del libro "Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy" por Manuel Delanda

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Manuel Delanda en Intensive science & virtual philosophy

For the purpose of discussing the constraints guiding Deleuzes

constructive project, one historical example of typological thinking is

particularly useful. This is the classificatory practices which were

common in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, such

as those that led to the botanical taxonomies of Linnaeus. Simplifying

somewhat, we may say that these classifications took as a point of

departure perceived resemblances among fully formed individuals, followed by precise comparisons aimed at an exhaustive listing of what

differed and what stayed the same among those individuals. This

amounted to a translation of their visible features into a linguistic

representation, a tabulation of differences and identities which allowed

the assignment of individuals to an exact place in an ordered table.

Judgments of analogy between the classes included in the table were

used to generate higher-order classes, and relations of opposition were

established between those classes to yield dichotomies or more elaborate hierarchies of types. The resulting biological taxonomies were

supposed to reconstruct a natural order which was fixed and continuous,

regardless of the fact that historical accidents may have broken that

continuity. In other words, given the fixity of the biological types, time

itself did not play a constructive role in the generation of types, as it

would later on in Darwins theory of the evolution of species. 59

Deleuze takes the four elements which inform these classificatory

practices, resemblance, identity, analogy and opposition (or contradiction)

as the four categories to be avoided in thinking about the virtual.

Deleuze, of course, would not deny that there are objects in the world

which resemble one another, or that there are entities which manage

to maintain their identity through time. It is just that resemblances and

identities must be treated as mere results of deeper physical processes,

and not as fundamental categories on which to base an ontology. 60

Similarly, Deleuze would not deny the validity of making judgments of

analogy or of establishing relations of opposition, but he demands that

we give an account of that which allows making such judgments or

establishing those relations. And this account is not to be a story about

us, about categories inherent in our minds or conventions inherent in

our societies, but a story about the world, that is, about the objective

individuation processes which yield analogous groupings and opposed

properties. Let me illustrate this important point.

I said before that a plant or animal species may be viewed as defined

not by an essence but by the process which produced it. I characterize

the process of speciation in more detail in the next chapter where I also

discuss in what sense a species may be said to be an individual, differing

from organisms only in spatio-temporal scale. The individuation of

species consists basically of two separate operations: a sorting operation

performed by natural selection, and a consolidation operation performed by reproductive isolation, that is, by the closing of the gene

pool of a species to external genetic influences. If selection pressures

happen to be uniform in space and constant in time, we will tend to

find more resemblance among the members of a population than if

those selection forces are weak or changing. Similarly, the degree to

which a species possesses a clear-cut identity will depend on the degree

to which a particular reproductive community is effectively isolated.

Many plant species, for example, retain their capacity to hybridize

throughout their lives (they can exchange genetic materials with other

plant species) and hence possess a less clear-cut genetic identity than

perfectly reproductively isolated animals. In short, the degree of

resemblance and identity depends on contingent historical details of

the process of individuation, and is therefore not to be taken for

granted. For the same reason, resemblance and identity should not be

used as fundamental concepts in an ontology, but only as derivative

notions.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black StudyDocument173 pagesThe Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black StudyMinor Compositions100% (3)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Gymnastics WorkbookDocument30 pagesGymnastics Workbookapi-30759851467% (3)

- Pharmacy Student Handbook 2018-2019 FINALDocument205 pagesPharmacy Student Handbook 2018-2019 FINALMaria Ingrid Lagdamen PistaNo ratings yet

- Project Planning Putting It All TogetherDocument25 pagesProject Planning Putting It All TogetherPedro Carranza Matamoros100% (1)

- Course 463 Aircraft Structural Repair For Engineers-Part IDocument2 pagesCourse 463 Aircraft Structural Repair For Engineers-Part IAE0% (2)

- Hausa Literature 1Document10 pagesHausa Literature 1Mubarak BichiNo ratings yet

- Paternity Leave and Solo Parents Welfare Act (Summary)Document9 pagesPaternity Leave and Solo Parents Welfare Act (Summary)Maestro LazaroNo ratings yet

- (Sinica Leidensia) Doris Croissant, Catherine Vance Yeh, Joshua S. Mostow-Performing - Nation - Gender Politics in Literature, Theater, and The Visual Arts of China and Japan, 1880-1940-Brill AcademicDocument465 pages(Sinica Leidensia) Doris Croissant, Catherine Vance Yeh, Joshua S. Mostow-Performing - Nation - Gender Politics in Literature, Theater, and The Visual Arts of China and Japan, 1880-1940-Brill AcademiclucuzzuNo ratings yet

- Korean SourcesDocument6 pagesKorean Sourcesgodoydelarosa2244No ratings yet

- Mil Summative Quiz 1 CompleteDocument2 pagesMil Summative Quiz 1 CompleteEverdina GiltendezNo ratings yet

- Derrida Jacques Stiegler Bernard Echographies of Television Filmed InterviewsDocument90 pagesDerrida Jacques Stiegler Bernard Echographies of Television Filmed InterviewsAlejandro Fielbaum100% (1)

- Manuel de Landa - Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy (Ebook)Document251 pagesManuel de Landa - Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy (Ebook)Pablo PachillaNo ratings yet

- Manuel de Landa - Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy (Ebook)Document251 pagesManuel de Landa - Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy (Ebook)Pablo PachillaNo ratings yet

- Photographic Memory: Jeffrey EugenidesDocument2 pagesPhotographic Memory: Jeffrey EugenidesJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- TheConceptOfJusticeInGreekPhilosophy PDFDocument5 pagesTheConceptOfJusticeInGreekPhilosophy PDFJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- N. Katherine Hayles With Anne Burdick - 2007 - Writing MachinesDocument145 pagesN. Katherine Hayles With Anne Burdick - 2007 - Writing Machinesg3raldoNo ratings yet

- Kafka Masochism PDFDocument17 pagesKafka Masochism PDFJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- The Pale Fox M. Griaule & G. DieterlenDocument283 pagesThe Pale Fox M. Griaule & G. DieterlenMichael J Peterson96% (47)

- Discusión Sobre La Teoría de Los Afectos ("Affect Theory")Document28 pagesDiscusión Sobre La Teoría de Los Afectos ("Affect Theory")Juan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- About DeLandaDocument46 pagesAbout DeLandaquatenus2No ratings yet

- Realer Than RealDocument4 pagesRealer Than RealJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Justice in Greek PhilosophyDocument5 pagesThe Concept of Justice in Greek PhilosophyJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- Signifying Semiologies and Asignifying Semiotics in Production and in The Production of SubjectivityDocument47 pagesSignifying Semiologies and Asignifying Semiotics in Production and in The Production of SubjectivityJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- Signifying Semiologies and Asignifying Semiotics in Production and in The Production of SubjectivityDocument47 pagesSignifying Semiologies and Asignifying Semiotics in Production and in The Production of SubjectivityJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- War at The Age of Intelligent MachinesDocument117 pagesWar at The Age of Intelligent MachinesJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- Digitize This Book! The Politics of New Media, or Why We Need Open Access Now Electronic Mediations 2008Document312 pagesDigitize This Book! The Politics of New Media, or Why We Need Open Access Now Electronic Mediations 2008Juan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- Deleuze - Coldness and CrueltyDocument67 pagesDeleuze - Coldness and Crueltycbrown1186100% (1)

- Serres and Deleuze: Hermes and HumorDocument7 pagesSerres and Deleuze: Hermes and HumorJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- Palmer - Under Your SkinDocument11 pagesPalmer - Under Your SkinJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- Borges and SimulacrumDocument24 pagesBorges and SimulacrumJuan Pablo Anaya100% (1)

- Biography ImmortalDocument25 pagesBiography ImmortalJuan Pablo AnayaNo ratings yet

- PESO PresentationDocument62 pagesPESO PresentationIan TicarNo ratings yet

- Syllabus SPRING 2012Document5 pagesSyllabus SPRING 2012Soumya Rao100% (1)

- Science Lesson Plan 1Document2 pagesScience Lesson Plan 1api-549738190100% (1)

- PISA2018 Results: PhilippinesDocument12 pagesPISA2018 Results: PhilippinesRichie YapNo ratings yet

- New Sams Paper 2H Qu.7 (A7, A11 - Ao2) : 2. AlgebraDocument3 pagesNew Sams Paper 2H Qu.7 (A7, A11 - Ao2) : 2. AlgebraDahanyakage WickramathungaNo ratings yet

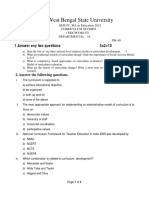

- West Bengal State University: 1.answer Any Two Questions: 5x2 10Document3 pagesWest Bengal State University: 1.answer Any Two Questions: 5x2 10Cracked English with Diganta RoyNo ratings yet

- People Development PoliciesDocument22 pagesPeople Development PoliciesJoongNo ratings yet

- ITIDAT0182A Develop Macros and Templates For Clients Using Standard ProductsDocument4 pagesITIDAT0182A Develop Macros and Templates For Clients Using Standard ProductsShedeen McKenzieNo ratings yet

- Siwestechnicalreport PDFDocument68 pagesSiwestechnicalreport PDFEmmanuel AndenyangNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument8 pagesUntitled DocumentAkshat PagareNo ratings yet

- Arrays GameDocument2 pagesArrays Gameapi-311154509No ratings yet

- Geometry Common CoreDocument4 pagesGeometry Common Coreapi-153767556No ratings yet

- De Cuong On Tap - AV - 4KN - Thang 2-2020Document59 pagesDe Cuong On Tap - AV - 4KN - Thang 2-2020Duc Trung TranNo ratings yet

- STS Module No. 3 For Week 3Document18 pagesSTS Module No. 3 For Week 3Joy Jane Mae OjerioNo ratings yet

- Cau 9Document2 pagesCau 9Du NamNo ratings yet

- Warm Up. Free Talk.: Marks ResourcesDocument2 pagesWarm Up. Free Talk.: Marks ResourcesМолдир ТуекеноваNo ratings yet

- DLL, December 03 - 06, 2018Document3 pagesDLL, December 03 - 06, 2018Malmon TabetsNo ratings yet

- ABWA Admission Details 2012-2013Document3 pagesABWA Admission Details 2012-2013adityarkNo ratings yet

- Grade 9 Edexcel English Language BDocument12 pagesGrade 9 Edexcel English Language BitsmeshimrithNo ratings yet

- A Passionate Teacher-Teacher Commitment and Dedication To Student LearningDocument7 pagesA Passionate Teacher-Teacher Commitment and Dedication To Student LearningKhairul Yop AzreenNo ratings yet

- Social GroupsDocument5 pagesSocial GroupsArchie LaborNo ratings yet