Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Drills For Teaching Sailing

Uploaded by

John M. WatkinsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Drills For Teaching Sailing

Uploaded by

John M. WatkinsCopyright:

Available Formats

Drills for teaching sailing

By John MacBeath Watkins

Ive been asked by my fellow sailing instructors at the Center for Wooden Boats to write up some of the drills I use for teaching. Because Im planning to post this where anyone with a computer can access it, I should explain what the Center for Wooden Boats is, what our sailing program is and why Im writing this. Those already familiar with the program can skip this part. The Center for Wooden Boats is a smallboat museum that aspires to preserve not just the objects of the era of wooden boats, but the skills associated with them. It started when Dick Wagner, an architect, decided to start a boat livery out of his houseboat. More about CWB here: http://www.cwb.org/ . Being a New Englander with an abiding affection for classic wooden boats, he started with a few Beetle Cats. The Beetle Cats attracted wooden boat buffs, and they wanted to talk about wooden boats, work on boats, build boats, and have classes about wooden boats. Eventually, Dick gave in to the inevitable and turned it into a museum, and moved it into new quarters at the south end of Lake Union.

I got involved with the Center in 1987. At that time Dick was doing all the checkout rides to make sure people could sail well enough to be trusted sailing what were, after all, museum exhibits. Not long after I joined, Dick asked me an a few others to help out with the checkout rides. One of those people was Vern Velez, who in 1989 came up with the idea of starting a sailing school associated with the Center for Wooden Boats, to be called Sail Now! He asked me to help him start it. We were having a problem with people coming down to rent a boat, certain that they could sail, and failing the checkout. They often had a certificate from some sailing program that said they had passed a sailing course. The problem, we realized, was that either the class had been too long ago, or the people running the course had taught them the regulation number of classes and given them a social promotion. Verns idea was to start a program with a clear goal: When they were done, people would be skilled enough to sail our exhibits. He proposed a program based on five lessons, with up to three students in the boat (usually the Blanchard Junior Knockabouts, a classic keelboat built on Lake Union) with an instructor. Some students learned in three lessons, others needed more than five, but they were all learning to sail well enough to take the boats out and in some cases learned well enough to become instructors. We were soon overwhelmed with students. Chris Glanister joined us as an instructor, then a few more. Vern had to step away from the program for a few months, so I ended up running it. I was at the time editing a

magazine, so I had to find a way to get other people to do most of the work. I put out a call for more instructors, told the staff they would have to take the calls to schedule the students, and instituted a program of tracking students progress with, initially, a piece of paper with their name at the top and the instructors comments about what conditions they had sailed in and what they had learned on the sheet. The sheet of paper is now a form which has been through several evolutions, but otherwise, the program runs pretty much the same way I set it up, though it is now big enough to require a person on staff to run it. The instructors are still volunteers. The sweetener I used to recruit the instructors initially was unlimited time in the boats for their own sailing, but that proved unnecessary. The joy of teaching is a deep and lasting one, and we never tire of it. Vern was able to come back after a few months, and while he was running the program it won a national award. Vern has now moved back to his native Puerto Rico, where he is helping with you guessed it a sailing program. Thats the basis for the program I teach in. The problem we now face is that as the program gets bigger, it gets harder to communicate between instructors and discuss what works and what doesnt. Thats why Im writing this.

On the psychology of students and instructors The pleasure of teaching comes mainly from two things: You always feels you are spreading light and joy when introducing people to an activity

you enjoy, and the process of learning a new skill makes people feel better about themselves. This means the instructors are (if they are any good) dealing with people whose self-esteem is blossoming under their care. (The concept of self-esteem is often misunderstood. It does not result from unwarranted praise, which produces only an addiction to praise. Rather, it comes from the feeling that what you do matters, the feeling that you can affect the world. That feeling comes from knowing you can do things, which is why learning a new skill is so pleasurable.) There are pitfalls along the way. Not all couples do well when learning together. In one case, I had to physically place myself between the man and woman, and explain quite clearly to the gentleman that the process works better if I do the instructing. In addition, when a couple learns a new skill, each of them has an equal chance of being better at it. The culture is changing, but I used to often see men struggling with the concept that their wives were better at sailing than they were. I have seen instructors fail to notice the progress of the quiet student, which can delay the assessment that they are ready to graduate, and on other occasions fail to notice the needs of quiet students who do not demand attention. It is the job of the instructor to focus on each student and make your own assessment of them. There is no link between being outgoing or demanding and being good at sailing, and the diffident student deserves as much attention as the brash one. Not everyone has the same sort of mind, which is why all the functions of our society can be accomplished without us all being geniuses. People who can visualize what is going to happen next will have a big

advantage in learning sailing, while those who are good at learning by rote will be at a disadvantage. Some are better at kinesthetic learning, and will respond to the feel of the boat better than visual cues. Often, language gets in the way, and pointing rather than talking helps the student more. Sometimes you have to shut up and let the student think, let them practice without your helpful hints so that they are responding to the boat rather than the instructor. Only occasionally should the instructor demonstrate the action; for the most part, the students should be running the boat with the instructors advice. Im not going to cover the things that are covered in ground school or the students textbooks, only some on-the-water drills that help structure the students time on the water in a productive way.

Drill 1: Steering Nothing will more effectively prevent a student from gaining confidence than a feeling that they are not in control of the boat. While children usually learn to steer in an instinctive manner quickly, adults tend to take a more analytical approach that can trip them up. If you see that the student is often pushing the tiller the wrong way, or is tentative and has to think too long before moving the tiller, you must convince them to stop thinking about the tiller and start thinking about where the boat goes. Thinking about the tiller while steering is like thinking about which foot to lift while walking; you would stumble at every step.

You must get the students mind outside the boat, looking to their destination and making the boat an extension of their body. Get the student to put the boat on a reach, then pick two possible destinations about two points apart.1 Tell them to head the boat first to one, then the other. Dont let them look at the tiller. Tell them the tiller moves two ways, so push it firmly one way, and if the boat goes the wrong way, push the tiller the other way. At this point I find its good to point out that mistakes are an important part of the learning process, and you want them to make big enough mistakes that they can see what they are doing wrong. That means dont be tentative with the tiller, be bold, screw up, and then do it right. Give them a good five minutes or so of steering first to, say, the book depository on the hill, then to the grassy knoll two points to starboard of it, as soon as they are firmly on course to one heading back to the other. After a few cycles youll see their use of the tiller become rapidly more natural and fluid. Importantly, they will know what to do with they make a mistake and put the tiller over the wrong way practicing the error means practicing the solution, and they no longer have to think about what to do when they screw up.

Here Im referring to the 32 point circle people used to use when boxing the compass.

Drill 2: Sailing to windward Once Ive got them steering well, the first thing I teach students is to sail to windward. Its a big confidence builder, because any fool can make a boat go down wind thats what happens when the boat is drifting. Again, this helps the student feel in control of the boat, because it assures them that they need not be pinned on a lee shore. Sheet the boat close hauled, but not so tight that a small error will result in the jib backing and causing the boat to tack against the will of the student. Have the student turn the boat slowly toward the wind until the jib luffs. I find it helps to get them to watch the seams on the sail, and tell them it should look like a Wright Brothers wing. This helps them read when the wind is on the wrong side of the sail. Have then turn quickly away from the wind before they lose too much speed, then stop turning and check their course against the shore to make sure theyve stopped turning. Start testing up to windward again. At first, youll have to point out what is happening. After a while, you can just point to the sail luffing and theyll turn away. Eventually, you should be able to shut up and let them think, and theyll do it right without your help. Often, they start thinking of sailing to windward in terms of the tiller in relation to their body instead of the boat in relation to the wind. The cure for this is not to have them change sides when they tack, so that they have to think about the problem correctly.

Drill 3: Sailing to windward with eyes closed

Students are sometimes overwhelmed with the number of things they have to watch, and dont develop a feel for the boat. One simple way to cut the sensory input is to have them close their eyes. My first job teaching sailing was at a summer camp to the blind, and there I learned how easily the blind can learn to sail to windward. Do this drill on a day when the wind is steady and moderate, not too calm. Its the same as the previous drill, except that instead of looking for visual cues, they are feeling the loss of power as the sails luff. There should be enough wind to heel the boat, since that is one of the major kinetic cues they will feel. Youll find that many people sail better with their eyes shut. I suspect this is because some people have more of a kinetic, rather than visual, learning style. Once theyve mastered this, they will sail better to windward with their eyes open, as well.

Drill 4: Tacking Tacking is one of the easiest and most intuitive things for students to learn. Tell then to keep the mainsheet where it is so that they can tell when theyve finished the tack. All they have to do is steer the boat through the wind, then stop turning when the main fills on the other tack and check their course to make sure theyve stopped turning. If they have difficulty with this, its likely they are centering the tiller instead of watching where the boat goes. Again, it can help to have them tack a few times without

changing sides, so that they are thinking about the boat in relation to the wind and not the tiller in relation to their bodies.

Drill 5: Depowering in gusts On a gusty day, its a big confidence builder for students to learn that they are in control of how much the boat heels. Often, it helps to have then control either the sheet or the tiller rather than both, and use either the helm or the sheet to depower, so that they are comfortable with both methods. You should also use such occasions to teach then the fishermans reef keeping the jib in tight and luffing the main on purpose to reduce heeling when the wind is consistently strong and they havent had a chance to reef.

Drill 6: Jibing and chicken jibing This is perhaps the least intuitive thing for students to learn. In the nautical language of the 18th century it was said that a boat that wants to turn to windward was ardent and one that wants to turn to leeward is crank. I rather like those terms, because they give boats a character. Most boats are designed to be ardent (weather helm), so turning to windward is in essence giving the boat what she wants. Going down wind, the boat heels little, and if the boom is very long, its probably a bit ardent, so youre fighting the boat when you jibe. First, teach them to go downwind without jibing, which is at least as important a skill as jibing. In addition to watching any wind pennants the

boat may have, they should learn to watch for when the jib is blanketed by the main, and how to interpret the ripples pushed by the wind. Its good to point out to them that if the jib and main are both filling on the same side, they cant jibe. Next, explain the goal, which is to have the boat finish the jibe going down wind with the sail all the way out, so that the forces on the boat are pushing it forward, and it wont be knocked down. Explain that sheeting in reduces the power in the main when it catches the wind on the other side, and that releasing as soon as it comes across keeps it from spinning the boat and allows the forces on the sail to pull forward. Point out that the worst case is when they fail to stop turning soon enough, and fail to let the sail out, because that can produce a boat that is sideways to the wind with the sail in tight, a scenario for a knockdown or capsize. The actual turn is the least intuitive part of the jibe. Get them to look at where the mainsail is before the jibe, because thats the direction they will be turning. If they can remember that simple rule, theyll always turn in the right direction. Demonstrate a proper jibe, so they can see you take your downwind course, sheet in, make the slight turn and let the sheet slide through your hand as soon as the sail crosses, while canceling the turn. If they have difficulty executing jibes, you can take it apart a step further, and have them handle first the helm and then the sheet until theyve mastered all parts of the jibe. Then make sure youve got plenty of sea room and have them execute a series of jibes, perhaps five in a row, so that the maneuver becomes more natural.

It is best to point out the hazards of jibing in strong winds, and teach them the alternative, the chicken jibe. I tell them its what you do when youre too chicken to jibe, essentially a 270 degree tack. Its actually more intuitive than a real jibe, because youre pulling in the sheets as you head up and letting them out as you bear away. It helps to cement the purpose of the chicken jibe if you have them do it around a leeward mark.

Drill 7, the meta-drill: Sailing around a course I find it helps put all this into perspective, and show students why youve been learning all these drills if they sail to destinations. Ideally, that would mean sailing around a course, where they can practice sailing efficiently to windward, finding the lay line, trimming for various points of sail and jibing or chicken jibing. If you dont have a course handy, just tell them to sail toward destinations that will force then to practice these skills. At first, you should get then to tell you how they will get to their next destination before they go for it, so that they are forced to think things out. Realizing that they know how to go somewhere in the boat is one of the final confidence builders for new skippers.

Drill 8: Landings It strikes me that there are two main methods taught for landings. In one, the student sails at the dock at 90 degrees to it, turns just before hitting and stops right there. This depends on perfect timing, so is vulnerable to

mistakes. I prefer to teach then to sail to the dock as 45-50 degrees, so that they can luff the sails to slow the boat or sheet in if they dont have enough way on. I tell then to try to put the side of the bow right on the dock. If they execute perfectly, theyll turn just before touching. If they dont, they wont break the stem of the boat, but will hit the dock with a glancing blow. Get the student to describe how they will dock before they do it, to make sure theyve worked out whether they need to do a U-turn to head the boat into the wind. Have them practice several in succession, so that youre confident they can put the boat where they want it on the dock. Technique for a difficult landing: At some point, you're likely to have to land the boat in some unfavorable conditions where you aren't able to luff the boat to slow it. We used to regularly dock the San Francisco Mercury, a small keelboat, against a northfacing dock in north winds, and I worked out a technique that worked quite well for landing broadside to the wind. I'd come down the channel downwind with the main sheeted tight as possible, closing off the leach to avoid developing any power. As I got to the aft end of the mooring spot, I'd pivot 90 degrees with the main still tight and the jib backed. The boat would slide into the slip sideways. People who didn't pull this off either didn't sheet the main tight enough or didn't make the final turn tight enough, both of which could prevent them from scrubbing off enough speed to stall the keel. I'd try teaching this to students against an imaginary dock rather than a real one, but it's good for them to understand

the physics well enough to work out how to slow the boat down while going straight down wind, and how stalling the keel can be done on purpose.

Drill 9: Man-Overboard The man-overboard drill is conceptually simple, and similar to the landing, but a few students struggle with it. A chalk talk can help. I like to get the student to think the thing through, and not simply complete a set of pre-determined moves, because circumstances might make a given maneuver wrong when they actually need to pick someone up. I tell them to get downwind of the man overboard, (I call the fender or cushion were using Bob, since it does) come up to him, and stop. Additional students in the boat can participate by continuing to point to the man overboard from the first call, and picking him out of the water. This only works if I have them practice stopping the boat. Otherwise, even if they can describe how to stop the boat, they wont get far enough down wind. So, 1) tell them how to do the drill. 2) have them practice stopping the boat 3) throw the man overboard and let them do it. Sometimes they will spend a lot of time thinking about what to do, even if youve discussed it beforehand. Remind them that Bob is getting cold, and is not a strong swimmer. This might seem to put pressure on them, but thinking of the cushion as Bob adds sufficient levity to take it back off while making the exercise a little more concrete. It matters, of course, how you remind them about Bob; deadpan humor, no stress in your voice, works for me.

You might also like

- The Book of Forbidden WordsDocument258 pagesThe Book of Forbidden WordsJohn M. Watkins100% (6)

- The New Complete Sailing Manual PDFDocument168 pagesThe New Complete Sailing Manual PDFsea13100% (7)

- Sailing Mast RiggingDocument88 pagesSailing Mast RiggingAna Carla Martins80% (5)

- Sleight S. The Complete Sailing Manual, 2021Document448 pagesSleight S. The Complete Sailing Manual, 2021Muhammad100% (5)

- The - Handbook - of - Sailing (Bob Bond, 5th Ed 1992) PDFDocument353 pagesThe - Handbook - of - Sailing (Bob Bond, 5th Ed 1992) PDFTabletaUnicaNo ratings yet

- The Complete Sailing Manual 3rd Edition by Steve SleightDocument450 pagesThe Complete Sailing Manual 3rd Edition by Steve SleightAleksander Buryak100% (8)

- The Golden Helmet (2015) (Digital) (Salem-Empire)Document130 pagesThe Golden Helmet (2015) (Digital) (Salem-Empire)K K GhoshNo ratings yet

- Sailing Guide For Beginners: Lee-HoDocument48 pagesSailing Guide For Beginners: Lee-HoKB100% (3)

- Bluewater Cruisers: A By-The-Numbers Compilation of Seaworthy, Offshore-Capable Fiberglass Monohull Production Sailboats by North American Designers: A Guide to Seaworthy, Offshore-Capable Monohull SailboatsFrom EverandBluewater Cruisers: A By-The-Numbers Compilation of Seaworthy, Offshore-Capable Fiberglass Monohull Production Sailboats by North American Designers: A Guide to Seaworthy, Offshore-Capable Monohull SailboatsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Oughtred Ian Clinker Plywood Boatbuilding ManualDocument188 pagesOughtred Ian Clinker Plywood Boatbuilding ManualMaxi Sie100% (5)

- World Cruising Routes 1,000 Sailing Routes in All Oceans of The World (Jimmy Cornell)Document1,420 pagesWorld Cruising Routes 1,000 Sailing Routes in All Oceans of The World (Jimmy Cornell)Johann Sebastian Bach100% (1)

- Yacht MasterDocument262 pagesYacht MasterИрина Ђорђевић100% (7)

- Sailing InstructionsDocument42 pagesSailing InstructionsFrank100% (3)

- General Sailing WikiDocument90 pagesGeneral Sailing WikiarklazakNo ratings yet

- Sailing and Navigation Tips: The Magic of Six Degrees. Tony CrowleyDocument5 pagesSailing and Navigation Tips: The Magic of Six Degrees. Tony CrowleyTony100% (3)

- ASA 101 - 104 RequirementsDocument15 pagesASA 101 - 104 RequirementsPramod Nayak100% (1)

- Bond B. The Complete Book of Sailing - A Guide To Boats, Equipment, Tides and Weather, Basic, Advanced and Competition Sailing, 1990Document200 pagesBond B. The Complete Book of Sailing - A Guide To Boats, Equipment, Tides and Weather, Basic, Advanced and Competition Sailing, 1990VitBar100% (1)

- Sailing - Maximum Sail Power The Complete Guide To Sails, Sail Technology, and PerformanceDocument305 pagesSailing - Maximum Sail Power The Complete Guide To Sails, Sail Technology, and PerformanceJorge Quintas71% (7)

- Seaworthy Offshore Sailboat: A Guide to Essential Features, Handling, and GearFrom EverandSeaworthy Offshore Sailboat: A Guide to Essential Features, Handling, and GearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Complete Ocean Skipper Deep Water Voyaging Navigation and Yacht ManagementDocument463 pagesThe Complete Ocean Skipper Deep Water Voyaging Navigation and Yacht ManagementJoão Crespo100% (3)

- The Ultimate YatchmasterDocument382 pagesThe Ultimate YatchmasterkaikomcNo ratings yet

- Single Handed TipsDocument146 pagesSingle Handed TipsTom Cloud100% (3)

- Sailmakers ApprenticeDocument516 pagesSailmakers Apprenticelaukejas100% (14)

- Complete Yachtmaster 5ed 2007 Cunliffe 0713676167Document257 pagesComplete Yachtmaster 5ed 2007 Cunliffe 0713676167Luka Toncic100% (1)

- Sailboat Rigging, DIY Boat Owner, 2001Document0 pagesSailboat Rigging, DIY Boat Owner, 2001lchee29100% (3)

- MARINE Reference SmallDocument4 pagesMARINE Reference Smallgenglandoh100% (1)

- DMSC Sailing Course Manual Edition 1Document17 pagesDMSC Sailing Course Manual Edition 1Dave Kukla100% (5)

- Dead Reckoning and Estimated PositionsDocument20 pagesDead Reckoning and Estimated Positionscarteani100% (1)

- Basic KeelboatDocument94 pagesBasic KeelboatTabletaUnica100% (3)

- Sail Online Manual Revised v4Document13 pagesSail Online Manual Revised v4kalle78No ratings yet

- Why I Am Not An AtheistDocument8 pagesWhy I Am Not An AtheistJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Understanding Boat Design 55 PDFDocument1 pageUnderstanding Boat Design 55 PDFŁukasz ZygielNo ratings yet

- Yachtmaster Passages and Skipper Training. NEW Sep 11Document13 pagesYachtmaster Passages and Skipper Training. NEW Sep 11austow0% (2)

- Small BoatSailingDocument7 pagesSmall BoatSailingJohn G HermansonNo ratings yet

- Catalina 22 ManualDocument11 pagesCatalina 22 Manualnimrod20032003No ratings yet

- Best Sailing Tips 2012Document36 pagesBest Sailing Tips 2012Prepelix OnlineNo ratings yet

- Small-Boat Sailing - An Explanation of the Management of Small Yachts, Half-Decked and Open Sailing-Boats of Various Rigs, Sailing on Sea and on River; Cruising, Etc.From EverandSmall-Boat Sailing - An Explanation of the Management of Small Yachts, Half-Decked and Open Sailing-Boats of Various Rigs, Sailing on Sea and on River; Cruising, Etc.Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Fast Track to Cruising: How to Go from Novice to Cruise-Ready in Seven DaysFrom EverandFast Track to Cruising: How to Go from Novice to Cruise-Ready in Seven DaysNo ratings yet

- Cruising the Caribbean With Kids: Fun, Facts, and Educational Activities: Rolling Hitch Sailing GuidesFrom EverandCruising the Caribbean With Kids: Fun, Facts, and Educational Activities: Rolling Hitch Sailing GuidesNo ratings yet

- Sailing EssentialsDocument306 pagesSailing Essentialsalsdjf100% (2)

- RYA - Sail Cruising CoursesDocument4 pagesRYA - Sail Cruising CoursesMarcus Sugar0% (1)

- 1 - 3CW - 9 Passage Planning 5 South Coast Channel IslandsDocument21 pages1 - 3CW - 9 Passage Planning 5 South Coast Channel IslandsjannwNo ratings yet

- Essential Cruising Library GuideDocument7 pagesEssential Cruising Library Guidechrysmon100% (1)

- ASA 103 Test Prep GuideDocument5 pagesASA 103 Test Prep GuideRyanNo ratings yet

- Training Manual 2019-20 PDFDocument136 pagesTraining Manual 2019-20 PDFXi YuanNo ratings yet

- Ship HullDocument11 pagesShip HullVenice UngabNo ratings yet

- The Complete Trailer Sailor: How to Buy, Equip, and Handle Small Cruising SailboatsFrom EverandThe Complete Trailer Sailor: How to Buy, Equip, and Handle Small Cruising SailboatsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Rigging and Sailing Techniques for Racing LasersDocument93 pagesRigging and Sailing Techniques for Racing LasersZsombor FehérNo ratings yet

- Building Meerkat, A Very Small CatboatDocument8 pagesBuilding Meerkat, A Very Small CatboatJohn M. Watkins100% (8)

- Sailing ManualDocument113 pagesSailing ManualTomislav PavicicNo ratings yet

- Boat Speed GuideDocument7 pagesBoat Speed GuideErin HillierNo ratings yet

- Sail Configurations For Short Handed VoyagingDocument7 pagesSail Configurations For Short Handed Voyagingforrest100% (3)

- Practical Boat-Sailing: A Concise and Simple TreatiseFrom EverandPractical Boat-Sailing: A Concise and Simple TreatiseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- CES Wrong Answer Summary KusnaediDocument6 pagesCES Wrong Answer Summary Kusnaedinad67% (3)

- Prepare documents for RightShip inspection of XH NAVIGATOR at DampierDocument3 pagesPrepare documents for RightShip inspection of XH NAVIGATOR at Dampierbiao yang100% (2)

- YCC Sailing Course For BeginnersDocument42 pagesYCC Sailing Course For BeginnersUrt Django AlessandroNo ratings yet

- Anchoring Boat SafelyDocument2 pagesAnchoring Boat SafelyFajar IslamNo ratings yet

- Introduction For Coastal NavigationDocument16 pagesIntroduction For Coastal NavigationAndri Handriyan100% (1)

- 0621 Pocket Guide PrintoutDocument8 pages0621 Pocket Guide PrintoutMuhammadNo ratings yet

- Ocean Pioneers-Robbert DasDocument163 pagesOcean Pioneers-Robbert Dasborex19446No ratings yet

- Answers To Activities in The ReaderDocument6 pagesAnswers To Activities in The ReaderisabelNo ratings yet

- WHAT MAKES TRI TRI FASTDocument15 pagesWHAT MAKES TRI TRI FASTAlex GigenaNo ratings yet

- What Huck Finn Means To MeDocument4 pagesWhat Huck Finn Means To MeJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- God and MemesDocument9 pagesGod and MemesJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- God As An Imperfect Being of Doubts, Uncertainty, RegretsDocument5 pagesGod As An Imperfect Being of Doubts, Uncertainty, RegretsJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- To Read Is To Become A Stolen ChildDocument4 pagesTo Read Is To Become A Stolen ChildJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- The Blue Man Speaks of Octopus Ink and Link RotDocument4 pagesThe Blue Man Speaks of Octopus Ink and Link RotJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Sex, Death and The Selfish MemeDocument5 pagesSex, Death and The Selfish MemeJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Worship - Scenes in Southeast AsiaDocument10 pagesWorship - Scenes in Southeast AsiaJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- A Fish Who Worships FireDocument9 pagesA Fish Who Worships FireJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- God of DoubtDocument8 pagesGod of DoubtJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Songbirds of The Primate World and The Poets Who Fail To SingDocument6 pagesSongbirds of The Primate World and The Poets Who Fail To SingJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Death of An Affectionate ManDocument4 pagesDeath of An Affectionate ManJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- She Lept As Light As LaughterDocument1 pageShe Lept As Light As LaughterJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Flight of The EuphemismDocument4 pagesFlight of The EuphemismJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Canal Life in ThailandDocument9 pagesCanal Life in ThailandJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- The Role-Playing GameDocument2 pagesThe Role-Playing GameJohn M. Watkins100% (1)

- The Singularity We Fear - Morlocks, Eloi, and The Post-Human FutureDocument2 pagesThe Singularity We Fear - Morlocks, Eloi, and The Post-Human FutureJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- All I Ask Is A Small ShipDocument4 pagesAll I Ask Is A Small ShipJohn M. Watkins0% (1)

- Longing For PredationDocument1 pageLonging For PredationJohn M. Watkins100% (1)

- Sex and The Single Neanderthal: Interbreeding and ExtinctionDocument4 pagesSex and The Single Neanderthal: Interbreeding and ExtinctionJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Whoreson Jack BonesDocument24 pagesWhoreson Jack BonesJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- The "Neanderthal Enigma" and The Structure of ThoughtDocument5 pagesThe "Neanderthal Enigma" and The Structure of ThoughtJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Bohemians - The Journey of A WordDocument3 pagesBohemians - The Journey of A WordJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Only A Half Moon Is Granted Sundered LoversDocument1 pageOnly A Half Moon Is Granted Sundered LoversJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- The Torturer's ApprenticeDocument13 pagesThe Torturer's ApprenticeJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- For Him That Stealeth A BookDocument1 pageFor Him That Stealeth A BookJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- Why Sail Wooden BoatsDocument3 pagesWhy Sail Wooden BoatsJohn M. WatkinsNo ratings yet

- CES Test CertificateDocument2 pagesCES Test CertificateMahmoud MoustafaNo ratings yet

- CPA TCIG Safety Alert Cranes Out of and Back Into Service Rev 2 200514Document3 pagesCPA TCIG Safety Alert Cranes Out of and Back Into Service Rev 2 200514NageswarNo ratings yet

- Training Check List/Twelve Months As Per Solas Training ManualDocument3 pagesTraining Check List/Twelve Months As Per Solas Training ManualAshifurNo ratings yet

- COLREGS Answer - 2 PDFDocument9 pagesCOLREGS Answer - 2 PDFmarNo ratings yet

- Discover Dublins Docklands 6PDL HRDocument2 pagesDiscover Dublins Docklands 6PDL HRAndres MinguezaNo ratings yet

- Howe India Company ProfileDocument62 pagesHowe India Company ProfileowngauravNo ratings yet

- We're Not Afraid To Die. - .Document16 pagesWe're Not Afraid To Die. - .Anonymous100% (1)

- Escola Náutica English I Unit 1 - 1-1Document12 pagesEscola Náutica English I Unit 1 - 1-1Mickie DeWetNo ratings yet

- PSC Check List 1Document2 pagesPSC Check List 1Phùng Đức HiếuNo ratings yet

- Type of Vessels (Part 1) : Passenger ShipsDocument4 pagesType of Vessels (Part 1) : Passenger ShipsLobos WolnkovNo ratings yet

- RIBO 450 MED Certificate B1 Exp. 30.03.2023Document5 pagesRIBO 450 MED Certificate B1 Exp. 30.03.2023Шинед ОрехNo ratings yet

- Checklist Audit Ism Office EngDocument9 pagesChecklist Audit Ism Office EngAji ArnowoNo ratings yet

- Transport and Insurance For Import & Export Cargo: Khoa TH Ương M IDocument14 pagesTransport and Insurance For Import & Export Cargo: Khoa TH Ương M IMỹ PhươngNo ratings yet

- Draft Survey Report: G.T L/W LOA BR D LPP 1855.00 757.00 76.80 15.50 4.40 75.00Document5 pagesDraft Survey Report: G.T L/W LOA BR D LPP 1855.00 757.00 76.80 15.50 4.40 75.00Abu Syeed Md. Aurangzeb Al MasumNo ratings yet

- Cargo insurer wins damages case against shipping firmDocument2 pagesCargo insurer wins damages case against shipping firmYodh Jamin OngNo ratings yet

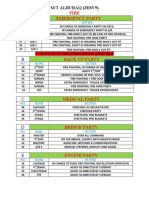

- Muster List Emergency DutiesDocument4 pagesMuster List Emergency DutiesAhmed AL BatalNo ratings yet

- 8 AKas NF Mi XXDocument49 pages8 AKas NF Mi XXHoài ThanhNo ratings yet

- Final ManuscriptDocument142 pagesFinal ManuscriptJerick NocheNo ratings yet

- CV Engineer Seeks PositionDocument1 pageCV Engineer Seeks PositionArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Language Stuff Language Stuff: For Printing The Reverse Side of The CardsDocument18 pagesLanguage Stuff Language Stuff: For Printing The Reverse Side of The CardsAin IzzatiNo ratings yet

- MT AZZA Q88 Vers. 5 Updated 22oct2022Document9 pagesMT AZZA Q88 Vers. 5 Updated 22oct2022Juan P. Rodriguez0% (1)

- SF Water Taxi Feasibility Study Executive SummaryDocument21 pagesSF Water Taxi Feasibility Study Executive SummarygksahaNo ratings yet

- Function 1 Bejo Ok & ReadyDocument137 pagesFunction 1 Bejo Ok & Readyoctavian eka100% (1)