Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Case Extracts Partnership Law

Uploaded by

billcwlimOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Extracts Partnership Law

Uploaded by

billcwlimCopyright:

Available Formats

PARTNERSHIP CASE EXTRACTS TAKEN FROM

Graw, S., (2001) An Outline of the Law of Partnership, 2nd Ed., Lawbook Co., Pyrmont, NSW.

Cox v Coulson [1916] 2 KB 177 (Graw 24; 2001)

Facts: Coulson leased and managed a theatre in which a touring company under the management of one C Watson Mill was performing a play. The financial arrangements were that Mill received 40 per cent of the gross box office receipts with the remaining 60 per cent going to Couslon. During a particular performance Cox, a member of the audience, was injured when a weapon being used as a prop (and which should not have been loaded) accidently discharged. Cox sued and the court had to decide whether Coulson, who had not been directly concerned with the specifics of the performance, could be made liable. Held: Coulson could be liable but only as an inviter potentially in breach of his duty to invitees entering his theatre. He was not directly or vicariously responsible for the negligence of the actor either as his employer or as Mills partner. As Swinfen Eady LJ explained at 181: Although the gross takings were divided between them, there was not any partnership; each had to discharge his own separate liabilities in respect of the venture. The travelling expenses, the remuneration of the actors, the cost of the appliances had to be borne entirely by Mill. The theatre rent and outgoings, the cost of the lighting, and the cost of playbills were wholly to be borne by the defendant. One of them may have made a profit out of the venture, and the other might have made a loss. Neither of them had authority to bind the other in any way; there was no agency between them. The sharing of gross returns does not of itself create a partnership.

Cox v Hickman (1860) 8 HL Cas 268; 11 ER 431 (Graw 28; 2001)

Facts: Benjamin Smith and his son Josiah carried on business under the partnership name B Smith and Son. The business fell into financial difficulty and it was decided that the Smiths would assign their business to trustees, who would carry it on and pay its net income to the creditors. That net income was deemed to remain the Smiths property (though it was to be applied to pay their debts) and once all the debts were paid the assets of the business were to be returned to them. During the period of trusteeship, Hickman, a supplier, drew three bills of exchange on the business and the trustees accepted them, purportedly on behalf of the firm (thus making the firm liable to pay them when they matured). The bills were dishonoured when they became due. Hickman sued Cox and Wheatcroft, arguing that they were members of a partnership (consisting of the firms creditors) that was running the business and that they were, therefore, liable on the bills.

Held: The mere fact that Cox and Wheatcroft, as creditors, had actually shared in the profits of the business did not make them partners in that business or liable for its debts. They had not been carrying on the business in common in the required sense.

Stekel v Ellice [1973] 1 WLR 191; [1973] 1 All ER 465 (Graw 42; 2001)

Facts: The parties were chartered accountants, Ellice having practised for some considerable time in partnership with one Jennison. When Jennison died, Ellice took Stekel on as an employee on the clear understanding that, if things worked out, Stekel would be made a partner. Things did work out but Ellice delayed giving Stekel the promised partnership because there was some doubt as to how much the firm would have to pay Jennisons estate. As a compromise it was agreed that Stekel would become a salaried partner until the firms liability to the estate could be ascertained. A written agreement to that effect was signed in 1968 but it also stipulated that the salaried partnership was only to last until 5 April 1969 and that the parties would enter into a deed or agreement on or before that date making Stekel a full partner. The agreement went on to recite that Stekel was to receive a salary of 2000 per annum, that the capital of the firm was to be provided by and shall solely belong to Ellice, that the relationship could be terminated by notice and that, upon any such termination, Ellice was to be entitled to all the capital and clients of the firm. After this agreement had been signed the parties continued the practice as before except that, thereafter, Stekel had his name on the firms letterhead as a partner and, within the firm, he acted as if he were a partner. No further steps were actually taken to make him a full partner however and, in August 1970, Stekel left the firm and brought an action seeking an order that the affairs of the partnership be wound up and that all necessary accounts be taken. Held: In the circumstances, a partnership between Stekel and Ellice had come into existence. Although their agreement for Stekel to receive a salary and for Ellice to have sole ownership of the firms capital was unusual, the other aspects of their 1968 agreement and their actual conduct thereafter were all consistent with the existence of a partnership. That partnership had terminated through mutual agreement in August 1970 but, because under the terms of the 1968 agreement Stekel was to have no interest in the capital or clients of the firm upon termination, he had no entitlement to either a winding-up order or an account. On the question of the legal status of a salaried partner Megarry J commented at 199; at 473: It seems to me impossible to say that as a matter of law a salaried partner is not necessarily a partner in the true sense. He may or may not be a partner, depending on the facts. What must be done, I think, is to look at the substance of the relationship between the parties; and there is ample authority for saying that the question whether or not there is a partnership depends on what the true relationship is, and not on any mere label attached to that partnership. A relationship that is plainly not a partnership is no more made into a partnership by calling it one than a relationship which is plainly a partnership is prevented from being one by a clause negativing partnership.

Polkinghorne v Holland (1934) 51 CLR 143 (Graw 92; 2001)

Facts: Thomas Holland, his son Harold and Louis Whitington were partners in a legal practice. The plaintiff, Florence Polkinghorne, was one of Thomas Hollands long-time clients but much of her business was attended to by Harold rather than by his father. Most of that business was to do with the investment of Mrs Polkinghornes money which, up to that point, had mainly been put in government securities and in first mortgages over property. The return on those investments was not great and Harold advised her that better returns were available elsewhere. Specifically, he advised her to sell 4000 worth of inscribed stock and to invest the proceeds in SA Trust Investment Co Ltd, a company that Harold had formed, which was run by one of his friends and which Harold knew was a mere shell. He later advised her to sell a further 1000 worth of stock and to lend the proceeds to Secretariat Ltd, a company that he had also formed and which, again, was without any financial substance. Finally, he persuaded her to become a director of Secretariat Ltd and to guarantee its overdraft in exchange for a share in its profits. All of these investments failed and Mrs Polkinghorne lost the 5000 that she had invested and an additional 5475 for which she became liable under her guarantee. Harold had disappeared when these losses became known, so Mrs Polkinghorne sued his father and Whitington alleging that, as Harolds partners, they were liable for her losses. They argued that they were not liable because giving financial advice was not part of the ordinary course of the business of the firm. Held: Harolds partners were liable for the 5000 Mrs Polkinghorne had lost from her investments in the SA Trust Investment Co Ltd and in Secretariat Ltd but they were not liable for the 5475 that she had lost by guaranteeing Secretariat Ltds overdraft. They were liable for the first set of losses because, on both occasions, Mrs Polkinghorne had specifically approached Harold for advice on the financial merits of the proposals before making her investments. The Court accepted (at 158) that solicitors possess no special skill in the valuation of real property, of shares, or of marketable securities *and+ it is not in the course of their professional duty to advise upon such matters. However, the court then went on to note (at 159) that it was within their duty to give, carefully, such advice as they could. Therefore, when Mrs Polkinghorne had asked Harold for advice, he had been obliged to explain to her what might be done if she wished to ascertain whether the company was not insubstantial, whether its business was not speculative or chimerical, whether its promoters were not men without standing, and of informing her what further inquiries might be made into the business and profit-earning capacity of the concern, and of warning her of the danger of blind investment. Here, Harold had not only failed to do what was required of him as Mrs Polkinghornes solicitor, he had actively concealed from her his knowledge of the very real dangers that were involved in entering into any of the suggested investments. For this reason, his acts and omissions in advising her about those investments were acts or omissions in the ordinary course of the business of the firm and his partners were, therefore, liable. The losses on the guarantee, however, were different. The guarantee arrangement had not involved Harold acting in his professional capacity Mrs Polkinghorne had neither sought his advice nor asked him to act for her. What he had done was unconscionable and an abuse of the influence that his position as her solicitor had given him but it had not involved him doing anything in the ordinary course of the business of the firm. Therefore, neither his father nor Whitington were liable for the losses on the guarantee.

Harvey v Harvey (1970) 120 CLR 529 (Graw 111; 2001)

Facts: Harold Harvey owned a pastoral property. When he became too ill to work it, he entered into an agreement with his brother Horace under which Horace and his two sons undertook to work the property in partnership with him. Harold had originally intended to sell the property but Horace convinced him that the proposed arrangement was preferable. It gave Horaces sons some experience running a pastoral property and it also ensured that the land would be available for Harolds son Robin, then aged six, if he wanted to take it over when he got older. Harold was to bring into the proposed business certain stock and implements and the firm of H L Harvey and Sons (Horace) was to contribute labour and skill but no other capital. Harold was to take no active part in the enterprise but profits and expenses were to be divided equally between Harold and his brothers firm. When the partnership was dissolved, a dispute arose about whether the land had become partnership property (and, therefore, whether it had to be sold and the proceeds divided between Harold, Horace and Horaces sons). Held: The land had not become partnership property. The court accepted that Harold had never intended that it would become a partnership asset. In fact, his intention (and his brothers intention) was quite clear the property was to be run in partnership only until Harolds son Robin was old enough to take it over. The partnership arrangement was merely a means of ensuring that the property could be kept in Harolds hands until Robin was old enough to work it himself. Consequently, the land, including all improvements, had not become partnership property. It was, therefore, not divisible among the partners. (However, the final accounts were adjusted because Harold had not paid his fair share of the cost of those improvements while the partnership was on foot).

You might also like

- T3-Sample Answers-Consideration PDFDocument10 pagesT3-Sample Answers-Consideration PDF--bolabolaNo ratings yet

- Partnership Notes Class-1Document55 pagesPartnership Notes Class-1ochenronald100% (1)

- Consideration AssignmentDocument27 pagesConsideration AssignmentThong Chee Whei100% (3)

- Case Notes - Topic 4Document8 pagesCase Notes - Topic 4meiling_1993100% (1)

- Lecture 9 Hire Purchase LawDocument31 pagesLecture 9 Hire Purchase LawSyarah Syazwan SaturyNo ratings yet

- No 2 - PromoterDocument6 pagesNo 2 - Promoterroukaiya_peerkhan100% (1)

- 12 Bduk3103 Topic 8Document50 pages12 Bduk3103 Topic 8frizal100% (1)

- Bank of Credit and Commerce International SA V AboodyDocument44 pagesBank of Credit and Commerce International SA V AboodyNicole Yau100% (2)

- Notes On The Law On Banking in Uganda: Banking and Negotiable InstrumentsDocument17 pagesNotes On The Law On Banking in Uganda: Banking and Negotiable InstrumentsNathan NakibingeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2agency 1Document53 pagesChapter 2agency 1api-234400353100% (9)

- Letchemy Arumugan: V N AnnamalayDocument16 pagesLetchemy Arumugan: V N Annamalayfathintulip0% (1)

- Law Case SummariesDocument30 pagesLaw Case Summariesdownloader10280% (5)

- Delivery of Wrong QuantityDocument6 pagesDelivery of Wrong QuantityUriahNo ratings yet

- LAW 416 - Assignment 3Document5 pagesLAW 416 - Assignment 3syaaismail100% (1)

- Case-Section 3 (1) Partnership Act 1961 Malayan Law Journal UnreportedDocument16 pagesCase-Section 3 (1) Partnership Act 1961 Malayan Law Journal UnreportedAZLINANo ratings yet

- Memorandum and Articles of AssociationDocument31 pagesMemorandum and Articles of AssociationSelva Bavani SelwaduraiNo ratings yet

- MBL Indiv - AssgmntDocument2 pagesMBL Indiv - AssgmntNurulhuda HanasNo ratings yet

- Law of PartnershipsDocument37 pagesLaw of PartnershipsAurelie Beatrice Mourguin50% (2)

- TOPIC 1 - Sale of GoodsDocument49 pagesTOPIC 1 - Sale of GoodsnisaNo ratings yet

- Topic 10 Law of Partnership (Part I)Document23 pagesTopic 10 Law of Partnership (Part I)Ali0% (1)

- Company LawDocument6 pagesCompany LawJayagowri SelvakumaranNo ratings yet

- Topic 6 Debenture and LoanDocument15 pagesTopic 6 Debenture and LoanYEOH KIM CHENGNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Partnership LawDocument7 pagesTutorial Partnership LawLoveLyzaNo ratings yet

- Contract Tutorial 1Document32 pagesContract Tutorial 1Wendy ChyeNo ratings yet

- Sales of Good (SOGA)Document10 pagesSales of Good (SOGA)Luna latrisya100% (3)

- Moss v. Hancock.Document10 pagesMoss v. Hancock.Otieno Brian OdiwuorNo ratings yet

- Business Law TutorialDocument9 pagesBusiness Law Tutorialshanti100% (1)

- Tutorial Question - MistakeDocument3 pagesTutorial Question - MistakextNo ratings yet

- Banking Law CasesDocument6 pagesBanking Law CasesCaesar Julius0% (1)

- Adequacy of ConsiderationDocument3 pagesAdequacy of ConsiderationMohamad Alif Idid50% (2)

- Tutorial Law of AgencyDocument1 pageTutorial Law of Agencysnurazani100% (1)

- 05 Answer Plan - Director DutiesDocument2 pages05 Answer Plan - Director DutiesNoor Shukirrah100% (1)

- Final Assessment: Faculty of Business Management Diploma in Banking (Ba119) Business Law (Law 299)Document19 pagesFinal Assessment: Faculty of Business Management Diploma in Banking (Ba119) Business Law (Law 299)Khadijah MisfanNo ratings yet

- Test Law299 Covid 19Document3 pagesTest Law299 Covid 19Syamiza SyahirahNo ratings yet

- Relations Between Partners and Third PartiesDocument45 pagesRelations Between Partners and Third PartiesschafieqahNo ratings yet

- Tan Hee Juan by His Next Friend Tan See BokDocument4 pagesTan Hee Juan by His Next Friend Tan See BokAzmir Syamim0% (1)

- Expropriated PropertyDocument25 pagesExpropriated PropertyKamugisha JshNo ratings yet

- Assignment Law Q 26, 48, 78Document13 pagesAssignment Law Q 26, 48, 78Syahirah AliNo ratings yet

- Cases For Law of ContractDocument6 pagesCases For Law of ContractTasnim RuzNo ratings yet

- Week 4 CHAPTER 2 Law of Contract - PPT Subtopic 3 - Voidable ContractpptDocument25 pagesWeek 4 CHAPTER 2 Law of Contract - PPT Subtopic 3 - Voidable ContractpptFadhilah Abdul Ghani100% (1)

- Tutorial 3Document4 pagesTutorial 3fenson2006No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 AcceptanceDocument10 pagesChapter 2 AcceptanceR JonNo ratings yet

- LAW416 - Assignment 1 - 2020973515Document3 pagesLAW416 - Assignment 1 - 2020973515Your CrushNo ratings yet

- Equitable Principle in Land LawDocument3 pagesEquitable Principle in Land LawFarah Najeehah ZolkalpliNo ratings yet

- BAYLEY v.THE MANCHESTER, SHEFFIELD, AND LINCOLNSHIRE RAILWAY COMPANY.Document16 pagesBAYLEY v.THE MANCHESTER, SHEFFIELD, AND LINCOLNSHIRE RAILWAY COMPANY.ZACHARIAH MANKIRNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 LAW299Document7 pagesAssignment 1 LAW299syakira mustafarNo ratings yet

- Practice of Banking I Law and PracticeDocument171 pagesPractice of Banking I Law and Practicecarltawia100% (1)

- OFFERDocument35 pagesOFFERNur KhaleedaNo ratings yet

- Company Law Tutor 1Document4 pagesCompany Law Tutor 1Karen Christine M. Atong0% (1)

- Gilford v. Horne CaseDocument3 pagesGilford v. Horne CaseVaidheesh Murali100% (2)

- Termination of Contract by A BankDocument6 pagesTermination of Contract by A Bankkmeshack100% (11)

- Re Akoto and Seven Others v1Document3 pagesRe Akoto and Seven Others v1Kwesi Oppong100% (2)

- TutoDocument4 pagesTutoibrahim nasaieNo ratings yet

- Sample Question On Contract LawDocument6 pagesSample Question On Contract LawNik Nur Fatehah50% (2)

- MALAYAWATA STEEL BERHAD V GOVERNMENT OF MALA PDFDocument4 pagesMALAYAWATA STEEL BERHAD V GOVERNMENT OF MALA PDFMary Michael100% (1)

- United Asian BankDocument11 pagesUnited Asian BankIzzat MdnorNo ratings yet

- Case Brief - Pender V Lushington (1866) 6 CH D 70Document3 pagesCase Brief - Pender V Lushington (1866) 6 CH D 70bernice100% (1)

- Answer For Law of ContractDocument4 pagesAnswer For Law of ContractAzhari Ahmad50% (2)

- Constitutional History CourseworkDocument3 pagesConstitutional History CourseworkCynthia AumaNo ratings yet

- Agency 12Document8 pagesAgency 12Arlene CañonesNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1 - Written or Oral QuestionsDocument7 pagesAssessment 1 - Written or Oral Questionswilson garzonNo ratings yet

- Costing ChartbookDocument29 pagesCosting ChartbookSHRAVANNo ratings yet

- Packaging Company FinancialsDocument7 pagesPackaging Company Financialstmir_1No ratings yet

- Uptempo Shareholder Update Letter June 12th 2020Document7 pagesUptempo Shareholder Update Letter June 12th 2020Steve LiNo ratings yet

- Jet Airways Case - Group7Document2 pagesJet Airways Case - Group7NIDHIKA KADELA 24No ratings yet

- CIR Vs La Tondena Full TextDocument3 pagesCIR Vs La Tondena Full TextKatherine Jane UnayNo ratings yet

- CH 05Document74 pagesCH 05Kornel Gokinson100% (1)

- Real Estate Principles Real Estate: An Introduction To The ProfessionDocument11 pagesReal Estate Principles Real Estate: An Introduction To The Professiondenden007No ratings yet

- Modul Soal Tugas Mingguan AK1 - Semester Gasal 2022-2023Document11 pagesModul Soal Tugas Mingguan AK1 - Semester Gasal 2022-2023Okmi Fidearni ZandrotoNo ratings yet

- Agency Costs of Overvalued Equity: Michael C. JensenDocument17 pagesAgency Costs of Overvalued Equity: Michael C. JensenTilahun GirmaNo ratings yet

- 5 6145300324501422422 PDFDocument3 pages5 6145300324501422422 PDFBeverly MindoroNo ratings yet

- p4 Textbook Acowtancy Lecture Notes 1 20Document401 pagesp4 Textbook Acowtancy Lecture Notes 1 20Phebieon Mukwenha100% (1)

- Markel PDFDocument331 pagesMarkel PDFvikrant_16No ratings yet

- Individual Work No.1: ST CriteriaDocument2 pagesIndividual Work No.1: ST CriteriaNikoleta TrudovNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Act310Document26 pagesChapter 3 Act310Shibly SadikNo ratings yet

- CIR vs. CA YMCA G.R. No. 124043 October 14 1998Document1 pageCIR vs. CA YMCA G.R. No. 124043 October 14 1998Anonymous MikI28PkJc100% (1)

- Bowles Sporting Inc Is Prepared To Report The Following IncomeDocument1 pageBowles Sporting Inc Is Prepared To Report The Following IncomeAmit PandeyNo ratings yet

- FS QuestionsDocument5 pagesFS QuestionsDuyên BùiNo ratings yet

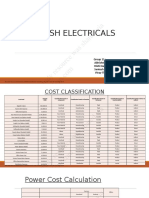

- Harsh Electricals: This Study Resource Was Shared ViaDocument9 pagesHarsh Electricals: This Study Resource Was Shared ViaPintonov PutraNo ratings yet

- Iefinmt Reviewer For Quiz (#1) : I. Multiple ChoiceDocument7 pagesIefinmt Reviewer For Quiz (#1) : I. Multiple ChoicepppppNo ratings yet

- Major Decisions in Finance ManagementDocument33 pagesMajor Decisions in Finance ManagementNandita ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Statement of Financial Position: 1. True 6. True 2. False 7. True 3. True 8. False 4. False 9. True 5. True 10. FALSEDocument10 pagesStatement of Financial Position: 1. True 6. True 2. False 7. True 3. True 8. False 4. False 9. True 5. True 10. FALSEMcy CaniedoNo ratings yet

- Accounting StandardsDocument10 pagesAccounting Standardschiragmittal286No ratings yet

- O Level MCQDocument77 pagesO Level MCQTaimoorNo ratings yet

- Calculating Enterprise ValueDocument8 pagesCalculating Enterprise ValueMerleNo ratings yet

- Sample Financial PlanDocument12 pagesSample Financial PlanSneha KhuranaNo ratings yet

- MA - Cost Accounting Techniques: Materials: Procedures and DocumentsDocument31 pagesMA - Cost Accounting Techniques: Materials: Procedures and DocumentsBhupendra SinghNo ratings yet

- SBR NoteDocument27 pagesSBR Notejeewen thienNo ratings yet

- Fair Value of Net AssetsDocument8 pagesFair Value of Net AssetsGanbilegBatnasanNo ratings yet

- Gratittude Manufacturing Company Post-Closing Trial Balance DECEMBER 31, 2017Document3 pagesGratittude Manufacturing Company Post-Closing Trial Balance DECEMBER 31, 2017Charles TuazonNo ratings yet