Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Article Explores The Laclau and Mouffe

Uploaded by

Rizky DarmawanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Article Explores The Laclau and Mouffe

Uploaded by

Rizky DarmawanCopyright:

Available Formats

Article Review (Muhibbuddin Murzan / 230 717 005) This Article explores the Laclau and Mouffes principal

about hegemony and Socialist Strategy (1985) which is supported with some texts written by Laclau alone. Traditionally, Discourse theory, by using discourse analytical tools in analyzing social phenomena, aims at understanding of the social as a separated construction. Discourse theory is suitable as a theoretical foundation for different social constructionist approaches to discourse analysis because of its broad focus, presenting the discourse theoretical approach to language and extending the theory to cover the entire social field. However, the Laclau and Moffes text do not include so many practical tools textually oriented discourses analysis, so that it can be useful to supplement their theory with methods from other approaches to discourse analysis. To sum up, the discourse theory views that the social phenomena are never finished. It means that the social phenomena can never be ultimately fixed and this opens up the way for constant social struggles about definitions of society and identify, with resulting social effects.

Toward a theory of Discourse In constructing their theory, Laclau and Moffen used the combination and modification of two major theoretical traditions namely Marxism and Structuralism. Marxism is a theory which is focus on social while Structuralism provides a theory of meaning. Laclau and Moffe combine these traditions into a single poststructuralist theory in which the whole social field is understood as aweb of processes where meaning is created. In the previous chapter, there was a suggestion toward the structuralism view of language that can be understood in terms of the metaphor of fishing-net : all linguistic signs can be thought of as knots in net, deriving their meaning from their difference from one to another, that is, from being situated in particular positions in the net. The poststructuralist objection was that meaning cannot be fixed so unambiguously and definitively. Poststructuralists agree that signs acquire their

meaning by being different from each other. , but, in ongoing language use, we position the signs in different relations to one another so that they may acquire new meanings. Thus language use is a social phenomenon: it is through conventions, negotiations and conflicts in social contexts that structures of meaning are fixed and challenged. But lets start off with Laclau. First of all we need a sense of his (and of course Mouffes too) definition of discourse. For him, the intrinsic emptiness in all discourses is what constitutes them as unstable, inessential and contingent formations. No discourse can be a complete entity i.e. a social construction that would be independent from all other constructions because that would mean that the construction would be essentially given and resistant to change. It would be a meta-physical entity that we couldnt even begin to understand. This is exactly the problem with the structural linguistic theory of Saussure from who Laclau and Mouffe starts off. In his well known Course in General Linguistics (1974) Saussure portrayed a linguistic structure as a system of difference where every sign gets its meaning from its relational position vis--vis other signs. In such a system meaning is only constituted through difference and every sign becomes nonessential in character, but on the other hand, the meaning of the system itself becomes essential something in itself as it is not standing in relation to anything at all. The relational positions of the included signs thus become fixed which means that meaning itself is fixed. Meaning is still arbitrary yes, and still relational yes, but yet it remains fixed. Even Saussure recognized this problem and because of that he included the time-factor in his theoretical body. Linguistic change, he postulated, can only come from something as undefined and un-theorized as time itself (1974: 73-74). Because of this theoretical problem Laclau and Mouffe introduced several notions, among them their concept of the field of discursivity (1985/2001: 111) a field in which every discursive formation partakes in and which they cannot fully master. The field of discursivity is characterized by infinitude, i.e. by the multitude of meaning that every object/sign/element can take. This field conditions every object as discursively constituted, while at the same time it prevents every attempt to fix their meaning, since they can always be put in new relational constellations, which would assign them new meanings. Every discourse thus becomes a semistable fixation of the field of discursivity and there is always something outside every discursive formation structure in Saussures terminlogy. This outside makes every discourse into a non-

complete entity, which allows us to theorize about structural change. But it also allows us to theorize about power and it is for that latter analysis that the concept of empty signifier is of the utmost importance. The field of discusivity allows us to understand the non-complete character of meaning, but it doesnt allow us to understand how a semi-stable meaning actually is constructed. As Laclau and Mouffe says: Even in order to differ, to subvert meaning, there has to be a meaning. (1985/2001: 112), and how is this meaning constructed? How is it that certain elements in the field of discursivity actually become connected to one another and thus turn themselves into a chain of relational positions (which is Laclau and Mouffes definition of discourse)? This is where the empty signifier comes into play. The empty signifier is the discursive centre, what Laclau & Mouffe calls a nodal point, i.e. a privileged element that gathers up a range of differential elements, and binds them together into a discursive formation. But it is only by emptying a certain signifier of its content that this process can be achieved. Its emptiness makes it possible for it to signify the discourse as a whole. The power of a certain signifier is therefore coterminous with its emptiness. It is only through this emptiness that it can articulate different elements around it, and thus produce a discursive formation. (As David wrote in his Notebook entry on Rauschenbergs Mother of God (notebook): The centre is at the same time both brilliant and actually pretty much nothing at all). With this emptiness the nodal point becomes universal in its scope, but it cannot be completely universal, since it is only given meaning by the particular elements, which it stands in relation to. Rather it is becomes a signifier of an absent universality of a lack within the discourses core. It becomes: present as that which is absent; it becomes an empty signifier, as the signifier of this absence (Laclau, 1996: 44) The centres emptiness is what makes discourses possible, but at the same time they condition every discourse as empty as a non-complete formation. The discursive centre, far from being an identifiable centre with a given positive content thus becomes a function of negativity, i.e. a function of something that the discourse lacks, to use Lacanian terms. We can now begin to understand how this emptiness is related to power, not only the power to be able to construct a discursive formation, but also as a power-struggle between formations. For

Laclau, the empty, incomplete character of every discourse is the driving factor behind politics as such. Politics, looked at from this perspective, then becomes a struggle to fill the emptiness with a given content to suture the rift of the discursive centre and to create a universal hegemony. The political struggle is therefore a struggle of identification, of obtaining a full/complete/positive/essential identity. An impossible project, but nevertheless a project that political discourses undertake. It would be a project aiming at the end of meaning and at the end contingency; towards the realization of a society fully reconciled with itself (Laclau, 1996, 69). Given the impossibility of this project, antagonisms are introduced as the symbol of my non-being (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985/2001: 125), of what keeps the political project from realizing itself, i.e. from obtaining a positive identity and thus establish hegemony. So the antagonistic relationship what keeps us from Ourselves (with a capital O) is the only type of identity we can obtain. Partial, yes, but at least semi-stable.This is exactly what privileges the antagonistic relationship in Laclaus body of theory, because it constructs the antagonistic relationship as the moment of individuation, as constitutive of the discursive formation, using Torfings wording: the outside is not merely posing a threat to the inside, but is actually required for the definition of the inside. The inside is marked by a constitutive lack that the outside helps to fill. (2004: 11) So the discursive centre is empty and needs to be filled, this is the very notion of politics that Laclau has brought us. A notion that always produces antagonisms, since Laclaus notion of politics determines that the emptiness within needs to be filled with a given content. What keeps us from performing that operation (which is actually the field of discursivity) is symbolically articulated as an antagonism. So the only identity that we can obtain, according to Laclau, is this antagonistic version of being kept from Oneself. But what if we could portray that inherent emptiness in other terms, terms that would still address discourses as lacking identity, but not necessarily illustrate their centres as something that needs to be filled/mastered by political projects or even identified as possible to be filled for that matter which would inevitably produce a symbol for that projects failure (the antagonistic other)? What kind of effects would that reformulation have for the analyses of social relations and of processes of identification? Instead of focussing priori on one type of relationships, we would have an abundance of relationships all part in processes of identification and the moment of

individuation. Such a reformulation would widen social space such as it is portrayed by traditional anglo-saxan discourse theorists, and open up for a more nuanced and valid discourse analysis more in tune with the social. Or at least, thats what I feel.

Critique of Marxism Marxism and Communism have done better as social movements than as parties in power. As movements, they have been able to excite and galvanize the opposition. As parties in power, they have resorted to terror and dictatorship to stay in power. When they have been democratic, they have been overthrown by the capitalist powers. The only communist regimes, which have successfully survived, are those, which have become capitalist. Since the collapse of communism in the East, the left in the West has also died along with it. Those who have chosen social democracy and reformism have increasingly become institutionalized and centrist so much that they are indistinguishable from the powers that be. Marxism has served as a kind of alter ego of modern capitalism. As long as capitalism has continued to grow and evolve, Marxism has been there to provide a critique of it. In order for capitalism to wipe out Marxism, it would first have to destroy itself. Then Marxists would have nothing about which to write. Or would they? Despite its vicissitudes, capitalism does not seem to be going away anytime soon. Its socially and environmentally destructive tendencies are only outmatched by its adaptability and tremendously productive capacities. The belief that civilization is on the verge of collapse ( la iek) echoes of hopes in the eschatological end of times. Neither the Messiah nor the Revolution has come. Belief in the apocalypse is based on a combination of anxiety and wishful thinking. More likely is that the crisis of crisis management will be managed. As much profit can be made out of helping the environment as in destroying it. Or, first we make money by destroying the environment so we can then make money by saving it. In an Orwellian logic, if we do not have an enemy we would have to create one. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, neo-conservative Samuel Huntington was all too eager but to point the way. For the right wing in the Judeo-Christian West, the new enemy is Islam. Arms contractors, oil companies, (along with Halliburton, Bechtel and Blackwater) have been all too eager but to get it

on what has mounted to a low grade endless wars- wars that cannot be won and which we do not want to win- on fear that we will lose our contracts. War is more profitable than peace. The underlying logic of the Obama administration is that the way to keep the military-industrial complex quiet (that is for the Democrats to have their support) is to keep them busy. If there is a desire to end a war due to its political and financial costs, it is only to free up resources for the next one. The Socialist, Communist, and Anarchist movements in the 19th and 20th century have not simply waned because of the collapse of the Soviet system; they have declined due to their own orthodoxy. Historical materialism and critical theory should be a living breathing framework, which constantly has to renew and modify itself to address changing conditions on the ground. In order for it to do so, it must engage in self-critique. Marx, wrote that the premise of all criticism is the criticism of religion. Conservative critics have accused Marxism of being a secular religion- a secularization of Judeo-Christian Messianism. This poses a paradox. On the one hand, it has provided hope in something better. On the other hand, it has been delusional. Rather than denying this, historical materialism must critique the theological residues within it so that it can once more become a vibrant social science. Only when this occurs, can it provide a truly critical understanding of existing social conditions and thereby provide any chance on making them better. One thing that a Marxist, historical materialist or a critical framework can provide is a better understanding of religion. There is a tendency of many social scientists to avoid dialectical frameworks for understanding social reality because of its political associations. Any association with Marxism gives most social scientistsUnbehagen. Marx did not invent dialectics nor was he the first to apply it to history, but he was the first to do it in a materialist manner, that is, supposedly devoid of theology. The roots of dialectics go back beyond Hegel and Kant to Plato and Aristotle. Dialectical frameworks still provide a useful tool in understanding the dynamics of historical processes. One of these dialectical frameworks is class analyses. However, it too often applied in a rigid manner. There are never just two classes but more complex divisions, subdivisions, and overlapping boundaries. Class is only one line along which conflict takes place. There others including race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, etc. Many of these conflicts have an economic basis. Neither Marx nor the Frankfurt School was the first to be critical. Preceding them were the Young Hegelians and Immanuel Kant. To be critical is not simply to negate but it is stems from the desire to make things better.

There is a tendency for most analyses of religion in the last few decades to engage in an empathetic understanding. While affirming freedom of belief and religious pluralism, we should not be afraid to criticize it. Religious beliefs need to be crosschecked with their relation to realitywhether literalist interpretations of the Bible, terrorism in the name of Jihad, or the delusions of the end of times. Individuals must have the right to religious freedom but we must challenge religious ignorance, Thanatos, and lack of self-reflection. To understand the religious conflicts in the modern world, we need to use a critical framework, which selectively appropriates elements from its intellectual past. The framework is self-reflective; critique turns back in on itself. Through critique, we can reach higher levels of understanding. Religious conflict is a process of interaction, and like all interaction, it has a dynamic. The pattern is not a cycle or a pendulum but rather a spiral (a dialectic). There is a tendency of sectarian religious movements to become institutionalized into churches. Social movements, if they survive, become institutionalized into NGOs or political parties. These institutions become increasingly ossified only to give rise to the need for new religious and secular movements. In the sphere of religion, the process with its periodic revivals and routinization is a dialectical one of religious rationalization and secularization. Critical theory needs to reevaluate its relationship to positivistic social sciences. It should make use of all methodologies available to it including quantitative, qualitative, and historical methods. A critical approach to religion will not be likely to attract institutional funding. Religious institutions and religious sympathetic foundations, especially conservative ones, are likely to be uninterested or even hostile. This is the problem of the left. Unlike our conservative and mainstream counterparts, we do not have much of an economic base. This, however, should not stop us. A critical approach to religion will help us better understand not only the roots of religious conflict, but also how it unfolds. It may help us make better sense of the religious right, of fundamentalisms and orthodoxies of all kinds, which stand in the way of progressive social change.

Antagonism and Hegemony

This article examines the implications of the introduction of the category of 'heterogeneity' in Ernesto Laclau's most recent work. Laclau's theory of hegemony and discourse theoretical approach to ideology is often associated with the category of 'antagonism'. I argue that heterogeneity should be the central category of hegemony and discourse analysis, and that antagonism can be seen as a strategy of ideological closure. In addition, heterogeneity understood as the simultaneous condition of possibility and impossibility of hegemonic articulation renders the theory of hegemony closer to Derridean deconstruction. Hegemony analysis and deconstruction are often presented as different and complementary theoretical moves. I argue that this is not the case, and that they can instead be seen as dealing with the same issues of the conditions of possibility and impossibility of the discursive constitution of ideology and identity. As having shown in Hegemony and Socialist Strategy, to be able to envisage negation in the mode of antagonism requires a different ontological approach where the primary ontological terrain is one of division, of failed unicity. Antagonism is not graspable in a problematic that sees the society as a homogeneous space because this is incompatible with the recognition of radical negativity. As Ernesto Laclau has stressed, the two poles of antagonism are linked by a nonrelational relation, they do not belong to the same space of representation and they are essentially heterogeneous with each other. It is out of this irreducible heterogeneity that they emerge. In order to make room for radical negativity, we need to abandon the immanentist idea of a homogeneous saturated social space and acknowledge the role of heterogeneity. This requires relinquishing the idea of a society beyond division and power, without any need for law or the state and where in fact politics would have disappeared. It could be argued that the strategy of exodus is the reformulation in a different vocabulary of the idea of communism as it was found in Marx. Indeed there are many points in common between the views of the Post-Operaists and the traditional Marxist conception. To be sure, for them it is not any more the proletariat but the Multitude which is the privileged political subject but in both cases the State is seen a monolithic apparatus of domination that cannot be transformed. It has to wither away in order to leave room for a reconciled society beyond law, power and sovereignty. If our approach has been called Post-Marxist it is precisely because we have challenged the type of ontology subjacent to such a conception. By bringing to the fore the dimension of

negativity which impedes the full totalization of society, we have put into question the very possibility of such a reconciled society. To acknowledge the ineradicability of antagonism implies recognizing that every form of order is necessarily a hegemonic one and that heterogeneity cannot be eliminated; antagonistic heterogeneity points to the limits of constitution of social objectivity. As far as politics is concerned, this means the need to envisage it in terms of a hegemonic struggle between conflicting hegemonic projects attempting to incarnate the universal and to define the symbolic parameters of social life. Hegemony is obtained through the construction of nodal points, which discursively fix the meaning of institutions and social practices and articulate the common sense through which a given conception of reality is established. Such a result will always be contingent and precarious and susceptible of being challenged by counter-hegemonic interventions. Politics always takes place in a field crisscrossed by antagonisms and to envisage it as acting in concert leads to erasing the ontological dimension of antagonism (that I have proposed to call the political) which provides its quasi-transcendental condition of possibility. A properly political intervention is always one that engages with a certain aspect of the existing hegemony in order to disarticulate/re-articulate its constitutive elements. It can never be merely oppositional or conceived as desertion because it aims at re-articulating the situation in a new configuration. Another important aspect of a hegemonic politics lies in establishing a chain of equivalences between various demands, so as to transform them into claims that will challenge the existing structure of power relations. It is clear that the ensemble of democratic demands that exist in our societies do not necessarily converge and they can even be in conflict with each other. This is why they need to be articulated politically. What is at stake is the creation of a common identity, a we and this requires the determination of a they. This again is missed by the various advocates of the Multitude, who seem to believe that it possesses a natural unity which does not need political articulation. According to Virno, for instance, the Multitude has already something in common: the general intellect. His critique (shared by Hardt and Negri) of the notion of the People as being homogeneous and expressed in a unitary general will which does not leave room for multiplicity and is totally misplaced when directed to the construction of the People through a chain of equivalence. Indeed in this case we are dealing with a form of unity that respects diversity and does not erase differences. As we have repeatedly emphasized, a relation of equivalence does not eliminate difference- that would be simply identity. It is only as far as democratic differences

are opposed to forces or discourses that negate all of them, that these differences can be substituted for each other. This is why the construction of a collective will requires defining an adversary. Such an adversary cannot be defined in broad general terms like Empire or for that matter Capitalism but in terms of nodal points of power that need to be targeted and transformed in order to create the conditions for a new hegemony. It is a war of position (Gramsci) that needs to be launched in a multiplicity of sites. This can only be done by establishing links between social movements, political parties and tradeunions. To create, through the construction of a chain of equivalence, a collective will, to engage with a wide range of institutions, with the aim of transforming them, this is, in my view, the kind of critique that should inform radical politics. Contingency and permence Contingency theories are a class of behavioral theory that contend that there is no one best way of leading and that a leadership style that is effective in some situations may not be successful in others. An effect of this is that leaders who are very effective at one place and time may become unsuccessful either when transplanted to another situation or when the factors around them change. This helps to explain how some leaders who seem for a while to have the 'Midas touch' suddenly appear to go off the boil and make very unsuccessful decisions.

You might also like

- Undoing Monogamy by Angela WilleyDocument38 pagesUndoing Monogamy by Angela WilleyDuke University Press100% (2)

- Laclau and Mouffe's Discourse Theory and Fairclough's Critical Discourse Analysis: An Introduction and ComparisonDocument26 pagesLaclau and Mouffe's Discourse Theory and Fairclough's Critical Discourse Analysis: An Introduction and Comparisonehsan nooriNo ratings yet

- 39 Laclau With Lacan: Comments On The Relation Between Discourse Theory and Lacanian PsychoanalysisDocument24 pages39 Laclau With Lacan: Comments On The Relation Between Discourse Theory and Lacanian PsychoanalysisRicardo Laleff Ilieff100% (1)

- Anne-Lysy Stevens Unconscious and InterpretationDocument10 pagesAnne-Lysy Stevens Unconscious and InterpretationRichard G. KleinNo ratings yet

- Kemal Pasha 1923Document8 pagesKemal Pasha 1923tam-metni.nasil-yazilir.comNo ratings yet

- Evaluate The View That Devolution Has Been A Success. (30) Politics Explained Essay PlanDocument5 pagesEvaluate The View That Devolution Has Been A Success. (30) Politics Explained Essay PlanlivphilbinNo ratings yet

- Constructing A Bridge PDFDocument468 pagesConstructing A Bridge PDFstavros_stergNo ratings yet

- The Names of The Real in Laclau's Theory PDFDocument18 pagesThe Names of The Real in Laclau's Theory PDFClaudia Mohor ValentinoNo ratings yet

- Jones Discourse LaclauDocument17 pagesJones Discourse LaclauZain SardarNo ratings yet

- Elder Vass 2011 Causal Power of Discourse JTSB PPVDocument28 pagesElder Vass 2011 Causal Power of Discourse JTSB PPVestranhasocupacoesNo ratings yet

- Deleuze As A Theorist of PowerDocument11 pagesDeleuze As A Theorist of PowerlukasNo ratings yet

- Malik Fixing MeaningDocument14 pagesMalik Fixing MeaningMorganElderNo ratings yet

- Political Protest and Metaphor: Charlotte FridolfssonDocument18 pagesPolitical Protest and Metaphor: Charlotte FridolfssonauniathirahNo ratings yet

- HOLLAND, J. The Capitalist UncannyDocument29 pagesHOLLAND, J. The Capitalist UncannyDavidNo ratings yet

- UygujhDocument10 pagesUygujhDamien PriestleyNo ratings yet

- Yeranuhi Khachatryan - Response Paper 3Document4 pagesYeranuhi Khachatryan - Response Paper 3Yeranuhi KhachatryanNo ratings yet

- Langue&ParoleDocument6 pagesLangue&ParoleBrincos DierasNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of Modern Linguistics: Language Et ParoleDocument9 pagesBasic Concepts of Modern Linguistics: Language Et Parolemuneeba khanNo ratings yet

- Blum&Nast Lefebvre&LacanDocument22 pagesBlum&Nast Lefebvre&LacanReidNo ratings yet

- Foucault On Discourse For Shakera GroupDocument8 pagesFoucault On Discourse For Shakera Groupfarabi nawar100% (1)

- Unit 5 Análisis Del DiscursoDocument21 pagesUnit 5 Análisis Del DiscursoRaquelSanchezNo ratings yet

- 4678-Article Text-12307-1-10-20210317Document23 pages4678-Article Text-12307-1-10-20210317Leila Al-AmudiNo ratings yet

- Is Another World' Possible? Laclau, Mouffe and Social MovementsDocument25 pagesIs Another World' Possible? Laclau, Mouffe and Social MovementsAL KENATNo ratings yet

- The Author / The Narrator / The CharacterDocument6 pagesThe Author / The Narrator / The CharacterMihaela Ramona100% (1)

- Conceptualization of IdeologyDocument9 pagesConceptualization of IdeologyHeythem Fraj100% (1)

- Salazar Andres-Final Essay-Research Seminar Political PhilosophyDocument15 pagesSalazar Andres-Final Essay-Research Seminar Political PhilosophyAndrés SalazarNo ratings yet

- Discourse, Discourse Analysis and C.D.ADocument59 pagesDiscourse, Discourse Analysis and C.D.Amarta soaneNo ratings yet

- GrammarDocument28 pagesGrammarmarcelolimaguerraNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Linguistics and Critical Discourse AnalysisDocument27 pagesCognitive Linguistics and Critical Discourse AnalysisEhsan DehghanNo ratings yet

- Discourse FoucaultDocument3 pagesDiscourse FoucaultdivyarajsinhNo ratings yet

- Articulation TheoryDocument12 pagesArticulation Theorylmcrg1971No ratings yet

- AlthusserDocument246 pagesAlthusserCyril SuNo ratings yet

- Significante e Dispotismo. Deleuze Critico Della LinguisticaDocument13 pagesSignificante e Dispotismo. Deleuze Critico Della LinguisticaakansrlNo ratings yet

- Dialogue at The BoundaryDocument21 pagesDialogue at The BoundaryTheo NiessenNo ratings yet

- Language and Power, Fairclough, CH 4Document4 pagesLanguage and Power, Fairclough, CH 4Malena BerardiNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To StructuralismDocument17 pagesAn Introduction To StructuralismAMAN kills47No ratings yet

- Halliday's Social Semiotic'Document5 pagesHalliday's Social Semiotic'craulmorNo ratings yet

- Samo Tomsic The Labour of Enjoyment Theoryleaks PDFDocument260 pagesSamo Tomsic The Labour of Enjoyment Theoryleaks PDFAldo Perán GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Notes On Michel Foucault-PowerDocument7 pagesNotes On Michel Foucault-Powerbharan16No ratings yet

- Notes On Barthes SZDocument8 pagesNotes On Barthes SZRykalskiNo ratings yet

- GlassMar'00 Policy Debate CritiquesDocument6 pagesGlassMar'00 Policy Debate CritiquesJuanpolicydebatesNo ratings yet

- Luca Leoni - PHD Written Exam 12-12-2023Document6 pagesLuca Leoni - PHD Written Exam 12-12-2023Luca LeoniNo ratings yet

- Luhmann - Speaking and SilenceDocument10 pagesLuhmann - Speaking and SilencenotizenNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor NowDocument40 pagesThe Contemporary Theory of Metaphor NowcheshireangekNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor - No PDFDocument39 pagesThe Contemporary Theory of Metaphor - No PDFLúciaKakazuNo ratings yet

- Lacan Deleuze and The Consequences of FoDocument16 pagesLacan Deleuze and The Consequences of Fodrfaustus1No ratings yet

- Articulation Theory A Discursive GroundDocument16 pagesArticulation Theory A Discursive GroundJosé LatabánNo ratings yet

- Mickunas-Discursos e IntercorporeidadesDocument16 pagesMickunas-Discursos e IntercorporeidadesSolve Et CoagulaNo ratings yet

- Discourse - WikipediaDocument8 pagesDiscourse - WikipediaAli AkbarNo ratings yet

- Structuralism and Post StructuralismDocument7 pagesStructuralism and Post StructuralismYasir JaniNo ratings yet

- Why Systemic Functional Linguistics Is The Theory of Choice For Students of LanguageDocument12 pagesWhy Systemic Functional Linguistics Is The Theory of Choice For Students of LanguageFederico RojasNo ratings yet

- Arte y NegociosDocument3 pagesArte y NegociosPaula MirandaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Mikhail BakhtinDocument21 pagesPhilosophy of Mikhail BakhtinGautam SarkarNo ratings yet

- The Project of Non-Marxism: Arguing For "Monstrously" Radical ConceptsDocument20 pagesThe Project of Non-Marxism: Arguing For "Monstrously" Radical ConceptsHeliogabalo de EmesaNo ratings yet

- Dance of The Dialectic OLLMANDocument30 pagesDance of The Dialectic OLLMANDom NegroNo ratings yet

- Kates Silence of ConceptsDocument20 pagesKates Silence of ConceptsgotkesNo ratings yet

- What Kind of Theory Do We Need For Translation?Document14 pagesWhat Kind of Theory Do We Need For Translation?smith858No ratings yet

- Structuralist Theories Report SummaryDocument3 pagesStructuralist Theories Report SummaryTeacherMhurzNo ratings yet

- Phillips (2006) - Rhetorical Maneuvers - Subjectivity, Power, and ResistanceDocument24 pagesPhillips (2006) - Rhetorical Maneuvers - Subjectivity, Power, and ResistanceMichael JohnsonNo ratings yet

- What Is The Impact of Language On SocietyDocument3 pagesWhat Is The Impact of Language On Societyyasra chNo ratings yet

- Structural Linguistics is an Approach to Language and Language Study Based on a Concept of Language as a System of Signs That Has Such Clearly Defined Structural Elements as Linguistic Units and Their ClassesDocument5 pagesStructural Linguistics is an Approach to Language and Language Study Based on a Concept of Language as a System of Signs That Has Such Clearly Defined Structural Elements as Linguistic Units and Their ClassesJellyNo ratings yet

- Barthes SemiologyDocument11 pagesBarthes Semiologysomsi yadavNo ratings yet

- The Barthes Effect. The Essay As Reflective TextDocument10 pagesThe Barthes Effect. The Essay As Reflective Textjosesecardi13No ratings yet

- Implementation of Health Behavior Change Principles in Dental PracticeDocument1 pageImplementation of Health Behavior Change Principles in Dental PracticeRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- List Jurnal Kedokteran Gigi Yang Bisa Diakses GratisDocument2 pagesList Jurnal Kedokteran Gigi Yang Bisa Diakses GratisRizky Darmawan83% (6)

- Umbrella (Edited)Document1 pageUmbrella (Edited)Rizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- On Sunday Ani DoesnDocument10 pagesOn Sunday Ani DoesnRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Muhib ADocument26 pagesMuhib ARizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- ItalyDocument5 pagesItalyRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Dress Code in IranDocument2 pagesDress Code in IranRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Istilah AkuntansiDocument2 pagesIstilah AkuntansiRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- The Myth of Malin KundangDocument1 pageThe Myth of Malin KundangRizky Darmawan100% (1)

- West LifeDocument5 pagesWest LifeRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Ichsan PoenjaDocument1 pageIchsan PoenjaRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Punya SaniDocument1 pagePunya SaniRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Immediate Complete Denture A Case ReportDocument4 pagesImmediate Complete Denture A Case ReportRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Procedure Manual For HSVDocument11 pagesLaboratory Procedure Manual For HSVRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Amalgam Risk BenefitsDocument1 pageAmalgam Risk BenefitsRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- Preventing of ECCDocument11 pagesPreventing of ECCRizky DarmawanNo ratings yet

- The LetterDocument10 pagesThe Letterderrick marfoNo ratings yet

- 2015 Lang Ques 2 Cesar Chavez Prose Analysis SamplesDocument8 pages2015 Lang Ques 2 Cesar Chavez Prose Analysis SamplesAleefNoorNo ratings yet

- Is India A Soft NationDocument2 pagesIs India A Soft Nationantra vNo ratings yet

- Jews N The Neo Cons-Heilbrunn & McdonaldDocument18 pagesJews N The Neo Cons-Heilbrunn & McdonaldDilip SenguptaNo ratings yet

- February 17Document6 pagesFebruary 17Hosef de HuntardNo ratings yet

- Transfer Certificate of Title No. T-85291Document3 pagesTransfer Certificate of Title No. T-85291Jezel Fate RamirezNo ratings yet

- Women Police in PakistanDocument43 pagesWomen Police in Pakistansouleymane2013No ratings yet

- JOURNAL ARTICLE, VOLUME, 1 (1) - 24, MARCH, 2019, Author: Onesmo Daniel Mkepule. Title: Tanu'S Supremacy and Patriotism of Mwalimu J.K NyerereDocument22 pagesJOURNAL ARTICLE, VOLUME, 1 (1) - 24, MARCH, 2019, Author: Onesmo Daniel Mkepule. Title: Tanu'S Supremacy and Patriotism of Mwalimu J.K NyerereAnonymous wApEsk4No ratings yet

- An Indian Perspective On New Development Bank & Asian Infrastructure Investment BankDocument11 pagesAn Indian Perspective On New Development Bank & Asian Infrastructure Investment BankCFA IndiaNo ratings yet

- DAVIS Et Al v. ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN Et Al - Document No. 1Document11 pagesDAVIS Et Al v. ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN Et Al - Document No. 1Justia.comNo ratings yet

- 1 The Separation of Church and StateDocument16 pages1 The Separation of Church and StatelhemnavalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 OutlineDocument4 pagesChapter 2 Outlinejason sheuNo ratings yet

- Results GazettedDocument4 pagesResults Gazettedyoyo200983No ratings yet

- Covering Victims of Armed Conflict: The Mindanao Experience: "The Role of Media in Protection of The Most Vulnerable"Document50 pagesCovering Victims of Armed Conflict: The Mindanao Experience: "The Role of Media in Protection of The Most Vulnerable"ReportingOnViolenceNo ratings yet

- The Anarchist PerilDocument296 pagesThe Anarchist Perilkolokotronis1770No ratings yet

- Zombies, Malls, and The Consumerism Debate: George Romero's Dawn of The DeadDocument17 pagesZombies, Malls, and The Consumerism Debate: George Romero's Dawn of The DeadMontana RangerNo ratings yet

- Baby Names Australia Report 2021Document18 pagesBaby Names Australia Report 2021Daniel millerNo ratings yet

- The Law of The SeaDocument65 pagesThe Law of The SeaNur Iman100% (1)

- Final-Final-Thesis 2Document74 pagesFinal-Final-Thesis 2Daniel DimanahanNo ratings yet

- Atal Bihari Horo by KN RaoDocument13 pagesAtal Bihari Horo by KN RaoRishu Sanam GargNo ratings yet

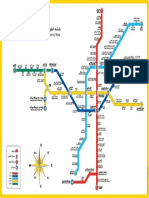

- Tehran Urban & Suburban Railway (Metro) Map: TajrishDocument1 pageTehran Urban & Suburban Railway (Metro) Map: TajrishthrashmetalerNo ratings yet

- 103 Phil. 1051 Tanada v. CuencoDocument2 pages103 Phil. 1051 Tanada v. CuencoK Manghi100% (1)

- John Locke Gen GoDocument11 pagesJohn Locke Gen GoragusakaNo ratings yet

- CollaborationDocument16 pagesCollaborationDarleneNo ratings yet

- Reserch Rough DraftDocument6 pagesReserch Rough Draftapi-314720840No ratings yet

- Picasso GuernicaDocument25 pagesPicasso GuernicaMarianna MusumeciNo ratings yet