Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Miller With Mark Upspdf

Uploaded by

api-42688552Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Miller With Mark Upspdf

Uploaded by

api-42688552Copyright:

Available Formats

Jeanetta Miller

Weaving Imagination into an Academic Framework: Attitudes, Assignments, and Assessments

An English teacher recommends two major writing projects that have helped expand students imaginations.

believe that imagination is alive in the high school classroom, but it is pale and sickly, suffering from a long decline in which we have conned it to its most decorous forms of expressioninference and interpretationand become ambiguous about whether or not it is truly welcome. What do we really want from students: cognitive leaps or compliance, passion or ve-paragraph essays, innovation or MLA format, wit or rigor? Imagination can be unruly and, worst of all, difcult to assess. Although the standards movement is often maligned, it grew, at least in part, out of a genuine desire to help students succeed in school by sharing information with them. At the high school where I teach, we wrote analytical rubrics to provide students with specic information about how to meet our graduation requirements. Many hours of committee work went into these rubrics. We learned that it is hard to write an analytical rubric that doesnt descend into meaningless increments of few, some, many. As we met and met again, there was a sense of excitement and satisfaction that we were moving toward consensus as a faculty on interdisciplinary standards for student work. This rubric was one of four that dene our standards for graduation in the areas of Information Literacy, Problem Solving, Written Performance, and Spoken Communication. We saw these rubrics as a way to communicate clearly and consistently to students what we, as a school community, value. It did not occur to us at the time that we had slighted an essential aspect of

learning, but I dont believe this is because any of us would have said that imagination is not important. Our focus was on nding a balance between reasonable expectations and academic rigor. If asked about imagination, we could have pointed out that imagination is implicit in standards such as makes inferences and promotes a new perspective or interpretation. The problem, of course, is that students will tend to focus on what is explicit in a rubric, such as the number of sources required. While I worry about the monster we might create in writing standards and rubrics that make the importance of imagination explicit, I think we owe it to students to set this record straight. However, adding an Imagination row to a rubric is not enough. To rouse imagination in the high school classroom, we need to convince students that they have the time and energy to engage imaginatively in the work they do for us. My experience suggests that this will not be easy.

Attitudes

Recently I conducted a survey of a representative cross-section of the junior class. The purpose of the survey was to determine how students dene success. I disaggregated the responses by gender and academic level and was a little stunned to nd that every group dened success primarily as good grades and admission to a respectable college. Some students also mentioned friends, family, being true to oneself, but they are all marching to the same

English Journal 99.2 (2009): 6773

67

Copyright 2009 by the National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved.

Weaving Imagination into an Academic Framework: Attitudes, Assignments, and Assessments

mantra: meet the standards, get the grades, go to college. Because they recognize that we are the gatekeepers, with authority to impose standards and determine grades, they comply with our demands, many of them putting in long hours to do so. Responses to the open-ended questions on the survey often alluded to the stress induced by the relentless pressure to produce work that will earn the necessary good grades. The survey results strongly suggest that many students operate in survival mode with no time or energy to engage creatively with assignments. A student in survival mode looks for the most direct route to the target grade; investing personal passion and imagination in simultaneous assignments from ve or six disciplines must seem not only impractical but downright irresponsible. I work in a district where curriculum, including standards and rubrics, is developed by teachers and then submitted to the Board of Education for approval. There is broad recognition that we need to maintain a balance between implementation of board-approved curriculum and freedom to experiment with new ideas and new approaches, so teachers will have fresh material to contribute when curriculum comes up for review. We realize that theres no such thing as a perfect curriculum, so we focus on continuous improvement. In each cycle of revision, our standards and rubrics more clearly reect the opportunities and imperatives of the 21st century. Nevertheless, as this process moves along, students are caught in a catch-22: to keep the door to the future open they must meet standards established ve or more years in the past, standards that tend to focus on the skills that are important to us rather than the skills that will be important to them. The Connecticut State Department of Education, in its Connecticut Plan for Secondary School Reform, cites Howard Gardners ve minds of the future, which include the disciplined mind of the critical thinker, the synthesizing mind of the problem solver, the creative mind of the innovator, the respectful mind of the collaborator, and the ethical mind of the leader (7). Connecticuts plan gives a central role to Gardners vision of future thinking: Those who live in the 21st century will need to practice all of these modes of thinking on a daily

basis. School must be the training ground for students to acquire and internalize these minds for success (7). If school is, indeed, to be this training ground, students need relief from the quantity of work they currently produce, so they have the time and the mental and emotional space to think critically, synthesize, innovate, collaborate, and develop the character to ethically lead. To that end, Ive been experimenting with assignments that lure students into spending more time and thought than they intended on the work. In return, Im giving fewer assignments and changing how the work is assessed.

Assignments

The Proteus Project

I was introduced to the Proteus Project by Laury Fischer at a Bay Area Writing Project workshop (http://www.bayareawritingproject.org/). The Proteus Project, as its name indicates, can take as many forms as there are individual students with a passion to know more about someone or something. It involves primary and secondary research and writing in the no-holds-barred tradition of New Journalism (Wolfe). In its current incarnation, my juniors work on the Proteus Project for the entire year, writing rst a nonction narrative, then a eld study based on the narrative, followed by intercalary chapters and a recurring motif (see g. 1 for assignment sheets and a rubric). The parts correspond with the readings for the course. For example, the nonction narrative follows a summer assignment focused on memoir, and the intercalary chapters are written after students have read The Grapes of Wrath and prior to reading In Our Time. The Proteus Project provides a exible framework, but it is the exercise of individual imagination that lls that framework with the interwoven threads of the students story, ndings, associations, visualization, revelations, and reections. The Proteus Project was already intuitively multigenre, as it integrates narrative with other patterns of exposition more typical of research papers. The inspiration to make Proteus explicitly multigenre came from an English Journal article by Nancy Mack. In her article Mack discusses in detail the power and possibilities of multigenre writing

68

November 2009

Jeanetta Miller

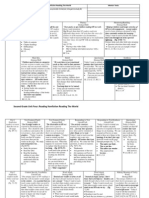

FIGURE 1. The Proteus Project

There in our hands he became a lion and a dragon and many other animals, and nally even a high-branched tree. But we held him rmly throughout, and at last he gave in and told me all I wished to know. Edith Hamilton

ongoing works cited/consulted. Select background reading from reliable sources, adding to the works cited/consulted. Write about your ndings. Intercalary Chapters Create three short pieces that expand on the central ideas of the nonction narrative and the eld study, using whatever genre is appropriate, and braid these pieces around the nonction narrative and eld study. Recurring Motif Establish a recurring motif that connects the ve pieces. The motif may take the form of image, graphic effect, text, or a combination. Conclusion Looking back at the nonction narrative, eld study, and intercalary chapters, write a conclusion that guides the reader toward a solid grasp of apt generalizations based on the specic illustrative detail of the individual components. The conclusion might include discussion of ndings, reection on process, personal or public implications, and questions for further study. Introduction Looking at the Proteus Project as a whole, write an introduction that provides readers with what they need to gain a full understanding of the project. The introduction might include a rationale for selecting the topic, major concepts, technical information, a glossary, illustrations, and information about the process. Cover Create a cover that uses graphic effect (visuals and text) to demand readers attention. If you accidentally dropped your project in the parking lot, the cover should be so striking that the next person passing could not resist picking it up. Works Cited and Works Consulted Include comprehensive works cited and works consulted lists, including sources for visuals. You may also include a bibliography of suggested readings. Table of Contents (TOC) If possible, format your Proteus Project as a single unied le and paginate. If this is not possible, print clean copies of each le and neatly hand paginate. The table of contents should include each component, title(s), and page numbers. continued

According to Edith Hamilton in Mythology, Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes, Proteus was one of the sea gods. He may have been Poseidons son or an attendant. Proteus could foretell the future and change his shape at will. When heroes got in trouble they looked to him for information. Proteus would only comply when captured and compelled to do so, which was not an easy task as he could shift his shape rapidly from one terrifying creature to another. Only the hero resolute enough to hold on through all the changes would be rewarded with knowledge. The challenge for todays heroes is not so much how to obtain information as how to decide what is worth knowing and worth caring about. The Proteus Project is an invitation to embark on a journey of exploration and epiphany, to wrestle ones own Proteus into submission. The project begins with and builds on a signicant personal narrative. The writer explores the true subject of the narrative, seeks information from other people about this subject, creates several pieces that grow organically out of the narrative and research, weaves a recurring motif through the evolving project, reects on ndings, and provides a cover and introduction that engage and inform the reader. Note: The title, focus on authentic sources, and student design of this project were inspired by an assignment developed by Laury Fischer of the Bay Area Writing Project. RE Q UIR E D CO M P O N E N T S O F TH E PR O TE US P R O J E C T Nonction Narrative Use the techniques of ction writers (see New Journalism) to write about a moment in your life that stands out, perhaps because you havent yet gured out why it lingers in your mind. Conduct background research to enlarge on prior knowledge and develop the moment into a nonction narrative, maintaining a works cited/ consulted list in MLA format. As you work on the nonction narrative, think about what the true subject might be (as opposed to the topic). Field Study Explore the true subject from your Nonction Narrative by seeking information from primary sources through interviews and a survey. Include these items in the

English Journal

69

Weaving Imagination into an Academic Framework: Attitudes, Assignments, and Assessments

FIGURE 1. Continued T H E P R OT EU S P R OJ EC T A SSESSM EN T RU BRIC Name ____________________________________________________________________________ Score ________ / 100 Procient Focus Develops a topic using more than one genre. Meets Goal Offers multiple perspectives on a topic using more than one genre. Advanced Makes imaginative use of an array of genres to explore a topic in depth and promote a new perspective or interpretation. Creates a logical organization, enhanced by specic techniques to increase coherence, such as repetitions, transitions, and graphic effects. Balances generalization and specic illustrative detail. Makes effective use of rhetorical strategies, including controlling tone, establishing and maintaining voice, and achieving appropriate emphasis through diction and syntax. Mechanical errors are rare; rules may be broken for effect. Selects information relevant to the research purpose from valid primary and expert secondary sources. Captures an important truth about human nature. Includes a substantial works cited/consulted in MLA format. Creates an attractive, userfriendly package. Presents an abstract of the project and performs excerpts from the project.

Concord

Organizes ideas within paragraphs and uses transition terms between paragraphs.

Organizes ideas within and between paragraphs and uses transition sentences between paragraphs. Develops engaging ideas and information with accurate, relevant details. Uses precise diction; writes concise, clear prose; conveys a distinctive voice.

Detail

Includes ideas and information that are generally well developed and accurate. Uses appropriate diction and writes clearly.

Liveliness

Conventions

There are some errors in mechanics. Selects information relevant to the research purpose from valid primary or secondary resources. Makes generalizations that are supported by the information selected. Attempts to cite resources in a works cited/consulted page in MLA format. Completes required components. Mentions the topic and reads an excerpt from the project.

There are few errors in mechanics. Selects information relevant to the research purpose from valid primary and secondary resources. Makes inferences that are supported by the information selected. Cites resources in a works cited/consulted page in MLA format. Houses the project neatly in a binder. Presents an overview of the project and reads excerpts from the project.

Information

Inferences

Sources

Package Presentation

Complete the assessment sheet and include it in the project. Each component is worth up to 10 points. Please attach a typed comment on the assignment. Discuss the sequence in which project components were assigned, problems you encountered in completing the project, aspects of the project that you particularly enjoyed, and suggestions for improvement.

70

November 2009

Jeanetta Miller

and concludes by compressing its characteristics into a concise list (see g. 2). Macks list has become part of the handout that I give students when they are about halfway through the Proteus Project and start to see that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. I compensate for the additional time and energy that students invest in the Proteus Project by making it serve as the nal exam for the course. An additional advantage of this is that there is no rush to complete a nal project or to cram for an exam when we near the end of the academic year. My goal is for all students to earn 100% of the possible points for the project, and most do.

The Occasional Paper

FIGURE 2. A Multigenre Paper requires that diverse types of writing be generated for a theme permits meaning to dictate form instead of vice versa presents multiple, conicting perspectives of one event or topic stimulates critical analysis and higher level thinking skills provides a rich context for an event or topic integrates factual information into a meaningful text versus copying or simple recall can incorporate interviews, oral history, folklore, and ethnographic research demonstrates a sophisticated knowledge of various types and uses of language creates coherence among the parts of a problem to be solved requires a bibliography, footnotes, and careful documentation of sources is almost impossible to plagiarize permits the author to highlight personal interests and special expertise can make full use of computers and multimedia imitates the format of modern novels and innovative business reports results in an aesthetically attractive product demands careful reading and response

Figure reprinted from Nancy Mack, The Ins, Outs, and In-Betweens of Multigenre Writing (97). Copyright 2002 by the National Council of Teachers of English. Reprinted with Permission.

Another assignment that has a signicant impact on my students willingness to truly engage in their writing is the Occasional Paper, which I discovered from an article by Bill Martin in English Journal. The article is called A Writing Assignment/A Way of Life and it has certainly become both for my students. The Occasional Paper, or OP, as it is fondly known, is a paper anchored in the quotidian. Already this year there have been OPs about writing utensil preference, PostSecret, switching roles with ones twin, Humpty Dumpty, National Novel Writing Month, and correct urinal behavior, to name just a few. Following Martins guidelines, the due date for the OP is exible and the paper is read aloud to the class. Students will sometimes offer me a copy, knowing that I collect samples for future students (and I sometimes beg for a copy), but the paper is not turned in for assessment. The only assessment students receive is the collective gasp or howls of

FIGURE 3. Guidelines for the Occasional Paper (OP) Things to Avoid Attacks on an individual or divulging information about an individual that should be kept in condence Formulaic organization with rote introduction and conclusion (ve-paragraph essay approach) A paper that is brief, undeveloped, or lacks detail Use of generic diction or clichs, reliance on sweeping generalizations about life Grammatical or usage errors Reading the paper for the rst time in class; trying to read from a handwritten draft

laughter or awed Wow! of their colleagues response; their peers responses have proven to be a mighty motivator for work that combines critical thinking with imagination. I provide guidelines (see g. 3) and enter credit for a good faith effort.

Things to Do Explore the details of an occasion that would usually be dismissed as unimportant Let the paper grow organically from ideas and purpose (tends to be organized inductively) Blend description, narrative, and exposition to engage the audience Make effective use of rhetorical elements such as tone, diction, syntax, imagery, and gurative language Break the rules for effect Practice reading the paper aloud before reading it in class and read from a typed, double-spaced script

English Journal

71

Weaving Imagination into an Academic Framework: Attitudes, Assignments, and Assessments

Students dont have to worry about the grade when they present their OPs; they have to worry about something much more important: moving a real audience with trenchant observation and artful use of language. Over the course of two or three rounds of OPs, students pick up new strategies, rene their craft both as writers and presenters, deepen their appreciation of their colleagues, and broaden their understanding of the foolishness and the sweetness of the world they inhabit.

Assessments

I dont mean to suggest that imaginative work cannot be subjected to the detailed, rigorous assessment that might be applied to literary or rhetorical analysis as long as the rubric makes what is valued explicit. The work of Carolyn Forch and Philip Gerard on creative nonction has been an invalu-

able resource for engaging students in writing that requires imagination as well as research and critical thinking and for developing a rubric to assess this type of work. The characteristics in the Exceeds Standard column of the rubric in Figure 4 were distilled from the introduction to Writing Creative Nonction: Instruction and Insights from Teachers of the Associated Writing Programs. This rubric ensures nonction has a purpose beyond information or analysis and attempts to capture in usefully explicit terms at least some of the characteristics of imaginative writing, which resist connement in columns and rows. My colleagues and I lament that, as the number of our students increases, our feedback tends to focus on what to x rather than what went well. At the beginning of the school year I vowed to experiment with using technology to provide more positive feedback, without devoting even more time than

FIGURE 4. A Creative Nonction Assessment Rubric Does Not Meet Standard 02 Characters are two-dimensional and the event or sequence of events is predictable or implausible. The piece is disorganized or unfocused. Meets Standard 3 Characters are three-dimensional and the event or sequence of events is interesting and believable. The piece is organized with an appropriate framework. Exceeds Standard 4 The true nature of the characters is revealed through narration of a signicant event or sequence of events. The piece is organized in a way that helps the reader grasp the true subject, using multiple genres, juxtaposition of conicting points of view, ashes back and forward, etc. The details reveal character and make the reader feel that he or she is present at the event or sequence of events. The foundation of the piece is memory, research, and the desire to capture an important truth about human nature. The piece is written in a voice that matches persona and intention. The writer conveys his or her perspective to the reader indirectly. There are no errors of mechanics or usage. The writer may break grammatical rules to achieve an effect. Score 04

The details are limited and/or clichd.

The details are relevant and carefully observed.

The foundation of the piece is solely the writers memory.

The foundation of the piece is primarily the writers memory, augmented with some background research. The piece is written with clarity and uency. The writer conveys his or her perspective to the reader both directly and indirectly. There are few errors of mechanics or usage.

Syntax is choppy or monotonous; diction is generic. The writer conveys his or her perspective directly through overt, didactic generalizations. There are many errors of spelling, punctuation, grammar, and other conventions of print.

72

November 2009

Jeanetta Miller

I already do to responding to student work. Most of my students are able to email their writing to me. Ive found that in the time it typically takes to note errors and write some cursory comments by hand, I can open documents in Microsoft Word, use the highlighting and Insert/Comment tools to make detailed comments, and type a substantial paragraph of feedback at the end of each piece that congratulates the students on their strengths and provides guidance for revision. After several rounds of experimentation, I asked my students for feedback. Although a few students preferred handwritten marginal comments and saw the word-processed comments as impersonal, most of them were enthusiastic about the detail and readability made possible by technology.

theres only so much that can be done at the local level. My students perspectives on how to achieve success are not just a reection of their experience in suburban Connecticut. Deep change can only occur if our national focus shifts from what can be quantied to the true quality of each students educational experience. With an administration in the White House focused on hope and change, and a host of problems clamoring for imaginative solutions, it seems like time to engage in a national conversation about how we dene a good education, time to have the audacity to propose that learning should be joyful, and time to include imagination in our national agenda.

Works Cited

Ensuring a Place for Imagination

While Im pleased with the results of the assignments and strategies Ive used to give imagination a legitimate place in a high school classroom, even in advanced placement classes, Ive also realized that resistance to change will continue to come from the direction in which I least expected it: students. To overcome this resistance, we must work within our discipline and across disciplines to rethink what we assign, how much we assign, and how we assess student work. I also recognize that

Connecticut Plan: Academic and Personal Success for Every Middle and High School Student. The Ad Hoc Committee for School Redesign. Hartford: Connecticut Department of Education, 2008. Print. Forch, Carolyn, and Philip Gerard, eds. Writing Creative Nonction: Instruction and Insights from Teachers of the Associated Writing Programs. Cincinnati: Story, 2001. Print. Mack, Nancy. The Ins, Outs, and In-Betweens of Multigenre Writing. English Journal 92.2 (2002): 9198. Print. Martin, Bill. A Writing Assignment/A Way of Life. English Journal 92.6 (2003): 5256. Print. Wolfe, Tom. The New Journalism. New York: Harper, 1973. Print.

Jeanetta Miller is English department chair at Newtown High School in Sandy Hook, Connecticut, where she teaches Honors English II and AP Language and Composition. She began her teaching career in the Albany Public Schools, Albany, California. She is a graduate of Mills College, Oakland, California, and earned her masters degree and administrative certication in Connecticut at Western Connecticut State University and Sacred Heart, respectively. Email her at millerj@newtown.k12.ct.us.

RE A D W R ITE THIN K C O N N E CT ION

Scott Filkins, RWT

Millers students create a multigenre paper to connect a memorable moment in their lives with original eld research on the true subject of that narrative. In Having My Say: A Multigenre Autobiography Project, students similarly historicize a story from their life, using a model text that combines rst-person storytelling and journalistic interchapters that provide historical and social context. http://www.readwritethink.org/lessons/lesson_ view.asp?id=1103

English Journal

73

You might also like

- Draft Engaged Learning Project B. Walsh: Improve Creativity in Our School AP English Language 10 GradeDocument6 pagesDraft Engaged Learning Project B. Walsh: Improve Creativity in Our School AP English Language 10 Gradeapi-509386272No ratings yet

- Ninth Grade Art of Persuasion Unit PlanDocument38 pagesNinth Grade Art of Persuasion Unit Planapi-534313864No ratings yet

- Project Based LearningDocument3 pagesProject Based LearningJoyce BringasNo ratings yet

- Orca Share Media1663084336676 6975481285658214501Document4 pagesOrca Share Media1663084336676 6975481285658214501Marc Dhavid RefuerzoNo ratings yet

- Jackson - The Lesson PlanDocument8 pagesJackson - The Lesson PlanJaviera FigueroaNo ratings yet

- 699-Final Research ProjectDocument13 pages699-Final Research Projectapi-257518730No ratings yet

- Argumentative Research Paper Rubric High SchoolDocument5 pagesArgumentative Research Paper Rubric High Schoolkkxtkqund100% (1)

- Thesis Teaching StrategiesDocument7 pagesThesis Teaching StrategiesArlene Smith100% (2)

- Two Types For Formative Assessment (GRADE 6)Document2 pagesTwo Types For Formative Assessment (GRADE 6)Jhea VelascoNo ratings yet

- Article ProofDocument4 pagesArticle Proofasha ashaNo ratings yet

- Lpcommentary 2Document2 pagesLpcommentary 2api-244609939No ratings yet

- Thesis About Hands On LearningDocument7 pagesThesis About Hands On Learningdngw6ed6100% (2)

- Strategies That Promote 21st Century SkillsDocument4 pagesStrategies That Promote 21st Century SkillsJoseph GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Teaching PhilosophyDocument3 pagesTeaching PhilosophyshelleynadiaNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Writing Course SyllabusDocument9 pagesDissertation Writing Course SyllabusOrderPapersOnlineCanada100% (1)

- Literature Review Closing Achievement GapDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Closing Achievement Gapvagipelez1z2100% (1)

- Project Based Learning Xi and X PDFDocument171 pagesProject Based Learning Xi and X PDFmfsrajNo ratings yet

- Principles of Teaching Term PaperDocument4 pagesPrinciples of Teaching Term Paperc5j2ksrg100% (1)

- Educators Are Continually Faced With New Challenges To Keep Up With LatestDocument7 pagesEducators Are Continually Faced With New Challenges To Keep Up With LatestLiza JeonNo ratings yet

- Simple Review of Related Literature ExampleDocument11 pagesSimple Review of Related Literature Examplec5qm9s32100% (1)

- Writing A Thesis GuidelinesDocument6 pagesWriting A Thesis Guidelinesaflpaftaofqtoa100% (2)

- Writing Style of ThesisDocument5 pagesWriting Style of ThesisCourtney Esco100% (2)

- SummativeDocument9 pagesSummativeapi-280905678No ratings yet

- Final Critical LiteracyDocument6 pagesFinal Critical LiteracyElmer AguilarNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Formative AssessmentDocument4 pagesLiterature Review of Formative Assessmentea219sww100% (1)

- Research Paper Topics For Elementary Education MajorsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics For Elementary Education MajorsgxkswirifNo ratings yet

- Teaching PhilosophyDocument3 pagesTeaching PhilosophyMatthew Vetter100% (1)

- Presenting The World CourseworkDocument5 pagesPresenting The World Courseworkafayepezt100% (2)

- Condon 2004Document20 pagesCondon 2004RATNA KUMALA DEWI, M.PdNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Recognizing AudienceDocument21 pagesLesson Plan Recognizing AudienceCPaulE33No ratings yet

- Facilitating Excellence in Academic and Clinical TeachingDocument10 pagesFacilitating Excellence in Academic and Clinical Teachingsapiah ramanNo ratings yet

- Topic:.Transforming Conceptual Learning Into Action.: Assignment: Art of LivingDocument14 pagesTopic:.Transforming Conceptual Learning Into Action.: Assignment: Art of LivingRubel HaqueNo ratings yet

- Online Course Design DocumentDocument12 pagesOnline Course Design Documentapi-215156967No ratings yet

- Synthesis John 2020Document11 pagesSynthesis John 2020api-510425539No ratings yet

- Literature Review of Early Literacy DevelopmentDocument7 pagesLiterature Review of Early Literacy Developmentfvet7q93100% (1)

- Wildwood NGLC Narrative Jan 2014Document5 pagesWildwood NGLC Narrative Jan 2014api-2567463150% (1)

- Bok Ctr-A.i. and Writing AssignmentsDocument11 pagesBok Ctr-A.i. and Writing Assignmentsismailnyungwa452No ratings yet

- Reading As ThinkingDocument9 pagesReading As ThinkingBlessing HarvestNo ratings yet

- Essay Coursework DifferenceDocument8 pagesEssay Coursework Differenceafjwfzekzdzrtp100% (2)

- 5 ComponentsDocument8 pages5 ComponentscollenNo ratings yet

- Project Based LearningDocument17 pagesProject Based LearningClaudita MosqueraNo ratings yet

- Homework As Authentic AssessmentDocument5 pagesHomework As Authentic Assessmentcfmfr70e100% (1)

- wp2 Final 1Document7 pageswp2 Final 1api-599878399No ratings yet

- The 5 E Instructional Model by CNLDocument64 pagesThe 5 E Instructional Model by CNLCB Ana SottoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Lesson PlansDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Lesson Plansngqcodbkf100% (1)

- Reflection About CourseworkDocument6 pagesReflection About Courseworkafjwftijfbwmen100% (2)

- Review of Related Literature Teaching EffectivenessDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature Teaching Effectivenessnadevufatuz2No ratings yet

- Teaching Thesis Statements To College StudentsDocument7 pagesTeaching Thesis Statements To College Studentsamyholmesmanchester100% (2)

- Authentic Pedagogy Newmann Issues No 8 Spring 1995Document15 pagesAuthentic Pedagogy Newmann Issues No 8 Spring 1995api-255466869No ratings yet

- Guidelines For Research Paper Middle SchoolDocument7 pagesGuidelines For Research Paper Middle Schoolc9rvcwhf100% (1)

- EDMC 532 - SyllabusDocument10 pagesEDMC 532 - SyllabusDjolikNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Titles For Early Years EducationDocument8 pagesDissertation Titles For Early Years EducationPayToWritePapersUK100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Template: Johns Hopkins University School of EducationDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Template: Johns Hopkins University School of Educationapi-379065695No ratings yet

- Conklin, W. (2012) - Higher-Order Thinking Skills To Develop 21st Century LearnersDocument170 pagesConklin, W. (2012) - Higher-Order Thinking Skills To Develop 21st Century Learners40. Krisna WijayaNo ratings yet

- Reflective Learning Statement Dissertation ExampleDocument6 pagesReflective Learning Statement Dissertation ExampleCheapCustomPapersPatersonNo ratings yet

- Teaching Writing Across The Curriculum Revised HandoutDocument3 pagesTeaching Writing Across The Curriculum Revised Handoutapi-307389925No ratings yet

- Discovery Approach: Creating Memorable LessonsDocument4 pagesDiscovery Approach: Creating Memorable LessonsAljo Cabos GawNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Educational FacilitiesDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Educational Facilitiesafmzfsqopfanlw100% (1)

- Introduction: Overview of The Key Problem or QuestionDocument4 pagesIntroduction: Overview of The Key Problem or QuestionSam YiiNo ratings yet

- Timeline 1900-1950Document1 pageTimeline 1900-1950api-42688552No ratings yet

- World MapDocument1 pageWorld Mapapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Charter Rights FreedomsDocument6 pagesCharter Rights Freedomsapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Timeline 1955-2005Document1 pageTimeline 1955-2005api-42688552No ratings yet

- Essay Scoring CriteriaDocument1 pageEssay Scoring Criteriaapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Description of Essay Organizers 2015Document2 pagesDescription of Essay Organizers 2015api-42688552No ratings yet

- Prime Ministers of CanadaDocument2 pagesPrime Ministers of Canadaapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Guiding Questions For July ReadingsDocument17 pagesGuiding Questions For July Readingsapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Geometry Ie UnitDocument6 pagesGeometry Ie Unitapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Story Structure Report Card To Parent To 1 PGDocument2 pagesStory Structure Report Card To Parent To 1 PGapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Part e Draft 4Document11 pagesPart e Draft 4api-42688552No ratings yet

- Teacher Generated Plot DiagramDocument1 pageTeacher Generated Plot Diagramapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Command Words For Socials EssaysDocument1 pageCommand Words For Socials Essaysapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Part D Draft 5Document10 pagesPart D Draft 5api-42688552No ratings yet

- Plot Diagram of GR 10 Socials Unit Draft 2Document1 pagePlot Diagram of GR 10 Socials Unit Draft 2api-42688552No ratings yet

- Kipp (Lindsey & Lauren'S Presentation) : Lunch BreakDocument5 pagesKipp (Lindsey & Lauren'S Presentation) : Lunch Breakapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Sage Caterpillars Draft 2Document5 pagesSage Caterpillars Draft 2api-42688552No ratings yet

- Sandra and LindaDocument20 pagesSandra and Lindaapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Guiding Questions For July ReadingsDocument12 pagesGuiding Questions For July Readingsapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Evaluation and DignityDocument5 pagesEvaluation and Dignityapi-42688552No ratings yet

- NW Rebellion Ie UnitDocument9 pagesNW Rebellion Ie Unitapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Karo and EmmaDocument22 pagesKaro and Emmaapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Colour - Ie UnitDocument4 pagesColour - Ie Unitapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Education 830 Assignment ADocument7 pagesEducation 830 Assignment Aapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Guiding Questions For June 8 and 9Document9 pagesGuiding Questions For June 8 and 9api-42688552No ratings yet

- Dimension Chart Eisner Draft 2Document9 pagesDimension Chart Eisner Draft 2api-42688552No ratings yet

- Presentation ScheduleDocument3 pagesPresentation Scheduleapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Part C Nina PagtakhanDocument2 pagesPart C Nina Pagtakhanapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Part B Nina PagtakhanDocument3 pagesPart B Nina Pagtakhanapi-42688552No ratings yet

- June 23 Independent StudyDocument4 pagesJune 23 Independent Studyapi-42688552No ratings yet

- Limba Engleza in AfaceriDocument139 pagesLimba Engleza in Afacerialexandru vespa100% (1)

- Internship ProposalDocument3 pagesInternship Proposalapi-409485902No ratings yet

- Usaid Schools ProjectDocument25 pagesUsaid Schools ProjectDennis ItumbiNo ratings yet

- Second Grade November-December Unit 4 NFDocument3 pagesSecond Grade November-December Unit 4 NFapi-169447826No ratings yet

- Ap English Literature Syllabus 2012Document11 pagesAp English Literature Syllabus 2012api-234597756No ratings yet

- Basa Pilipinas Teacher'S Guide: Grade 1 Mother Tongue (Sinugbuanong Binisaya)Document219 pagesBasa Pilipinas Teacher'S Guide: Grade 1 Mother Tongue (Sinugbuanong Binisaya)Vicente AnascoNo ratings yet

- Phyllis Creme, Mary Lea-Writing at University-Open University Press (2008) PDFDocument234 pagesPhyllis Creme, Mary Lea-Writing at University-Open University Press (2008) PDFJairo AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Reading Project Smart (Start Making A Reader Today) : Online Read To SucceedDocument12 pagesReading Project Smart (Start Making A Reader Today) : Online Read To SucceedJoan Bugtong100% (2)

- I-Ready Pop Evaluation PlanDocument10 pagesI-Ready Pop Evaluation Planapi-300094852No ratings yet

- What Is Annotation and Why Would I Do ItDocument1 pageWhat Is Annotation and Why Would I Do Itapi-237577048No ratings yet

- Cpe - Longman - New Proficiency Gold - Teacher S Book PDFDocument190 pagesCpe - Longman - New Proficiency Gold - Teacher S Book PDFIulia Tepes33% (3)

- Michael P. Henry Dissertation (2017), Curriculum and Instruction, Northern Illinois UniversityDocument510 pagesMichael P. Henry Dissertation (2017), Curriculum and Instruction, Northern Illinois UniversityDr. Michael HenryNo ratings yet

- CELTA Assignment 3 - SkillsDocument16 pagesCELTA Assignment 3 - SkillsHazel Fernandes75% (20)

- Reading Level Correlation ChartDocument1 pageReading Level Correlation Chartapi-245946315No ratings yet

- BINS 129 Tongue - Between Biblical Criticism and Poetic Rewriting - Interpretative Struggles Over Genesis 32 - 22-32 2014 PDFDocument304 pagesBINS 129 Tongue - Between Biblical Criticism and Poetic Rewriting - Interpretative Struggles Over Genesis 32 - 22-32 2014 PDFNovi Testamenti Lector100% (1)

- Kinds/ Types of Reading Recreational Reading Corrective/ Remedial ReadingDocument25 pagesKinds/ Types of Reading Recreational Reading Corrective/ Remedial ReadingSalvacion MabelinNo ratings yet

- Letter To Prof OgdenDocument2 pagesLetter To Prof Ogdenapi-288084378No ratings yet

- New Inside Out Upper Intermediate Practice OnlineDocument15 pagesNew Inside Out Upper Intermediate Practice OnlineVictor Andres Pretell Rodriguez0% (1)

- Criteria For Selecting Childrens LiteratureDocument2 pagesCriteria For Selecting Childrens LiteratureDalynai100% (1)

- Course Proforma ELE 3104 Sem. 6Document8 pagesCourse Proforma ELE 3104 Sem. 6Nur Syahwatul IsLamNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document32 pagesChapter 1ChomatNo ratings yet

- High School 9-12 Reading Curriculum GuideDocument23 pagesHigh School 9-12 Reading Curriculum GuidemrsfoxNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Form: III/English IIIDocument6 pagesLesson Plan Form: III/English IIIapi-439274163No ratings yet

- Reflection PaperDocument22 pagesReflection PaperJubsNo ratings yet

- Alternative ReadingsDocument9 pagesAlternative ReadingsElvin JuniorNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan XiiDocument5 pagesLesson Plan XiiIon PopescuNo ratings yet

- English Curriculum Guide Grades 1-10 PDFDocument168 pagesEnglish Curriculum Guide Grades 1-10 PDFLeo Vigil Molina Batuctoc100% (2)

- Lesson Plan 6 Sped 415Document2 pagesLesson Plan 6 Sped 415api-383897639No ratings yet

- IELTS Express Upper-Intermediate Unit 1 SBDocument8 pagesIELTS Express Upper-Intermediate Unit 1 SBRigoberto Carbajal ValdezNo ratings yet

- Test DesignDocument75 pagesTest DesignuwviiikiiNo ratings yet

- Seven Steps to Great LeadershipFrom EverandSeven Steps to Great LeadershipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice English Writing: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- David Baldacci Best Reading Order Book List With Summaries: Best Reading OrderFrom EverandDavid Baldacci Best Reading Order Book List With Summaries: Best Reading OrderNo ratings yet

- Colleen Hoover The Best Romance Books Complete Romance Read ListFrom EverandColleen Hoover The Best Romance Books Complete Romance Read ListNo ratings yet

- Myanmar (Burma) since the 1988 Uprising: A Select Bibliography, 4th editionFrom EverandMyanmar (Burma) since the 1988 Uprising: A Select Bibliography, 4th editionNo ratings yet

- Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyFrom EverandGreat Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- American Founding Fathers In Color: Adams, Washington, Jefferson and OthersFrom EverandAmerican Founding Fathers In Color: Adams, Washington, Jefferson and OthersNo ratings yet

- 71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersFrom Everand71 Ways to Practice Speaking English: Tips for ESL/EFL LearnersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Jack Reacher Reading Order: The Complete Lee Child’s Reading List Of Jack Reacher SeriesFrom EverandJack Reacher Reading Order: The Complete Lee Child’s Reading List Of Jack Reacher SeriesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Christian Apologetics: An Anthology of Primary SourcesFrom EverandChristian Apologetics: An Anthology of Primary SourcesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyFrom EverandGreat Short Books: A Year of Reading—BrieflyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Help! I'm In Treble! A Child's Introduction to Music - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical Instruction & StudyFrom EverandHelp! I'm In Treble! A Child's Introduction to Music - Music Book for Beginners | Children's Musical Instruction & StudyNo ratings yet

- English Vocabulary Masterclass for TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS and CELPIP: Master 1000+ Essential Words, Phrases, Idioms & MoreFrom EverandEnglish Vocabulary Masterclass for TOEFL, TOEIC, IELTS and CELPIP: Master 1000+ Essential Words, Phrases, Idioms & MoreRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Bibliography on the Fatigue of Materials, Components and Structures: Volume 4From EverandBibliography on the Fatigue of Materials, Components and Structures: Volume 4No ratings yet

- Sources of Classical Literature: Briefly presenting over 1000 worksFrom EverandSources of Classical Literature: Briefly presenting over 1000 worksNo ratings yet

- Patricia Cornwell Reading Order: Kay Scarpetta In Order, the complete Kay Scarpetta Series In Order Book GuideFrom EverandPatricia Cornwell Reading Order: Kay Scarpetta In Order, the complete Kay Scarpetta Series In Order Book GuideRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Political Science for Kids - Democracy, Communism & Socialism | Politics for Kids | 6th Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandPolitical Science for Kids - Democracy, Communism & Socialism | Politics for Kids | 6th Grade Social StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Chronology for Kids - Understanding Time and Timelines | Timelines for Kids | 3rd Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandChronology for Kids - Understanding Time and Timelines | Timelines for Kids | 3rd Grade Social StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Seeds! Watching a Seed Grow Into a Plants, Botany for Kids - Children's Agriculture BooksFrom EverandSeeds! Watching a Seed Grow Into a Plants, Botany for Kids - Children's Agriculture BooksNo ratings yet