Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Paper Panzers and Wonder Weapons of The Third Reich

Uploaded by

PeterD'Rock WithJason D'ArgonautOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Paper Panzers and Wonder Weapons of The Third Reich

Uploaded by

PeterD'Rock WithJason D'ArgonautCopyright:

Available Formats

PANZERKAMPFWAGEN VIII MAUS (1943-1945) By Rob Arndt The Tiger II King Tiger was not the largest German

tank created by the German tank industry. Much precious time and material was wasted on building prototypes of super-heavy tanks of gigantic proportion. Dr Ferdinand Porsche was the driving force behind the first of these, the 188-ton Maus (mouse), while the second type to be built, the 140-ton E-100, was supported by the Heereswaffenamt as a competitive design. Porsche got approval for his project from Hitler, at a time when none of his designs had been selected for production by the Heereswaffenamt. In this way Hitler might have compensated Porsche for the past failures, and it would keep him away from other projects. The turret had a rounded front made from a single bent plate of 93mm thickness. The armament was either a 128mm or a 150mm gun, plus a 75mm gun mounted co-axially. The first turrets, with a weight of 50 tons, were not complete until the middle of 1944, leaving the two prototypes with a simulated turret to complete trials in the winter of 1943-1944, at Krupp's test area in Meppen. Two more hulls were under construction during the closing months of the war, but in April 1944, Hitler personally ordered that all work on giant tank projects was to cease in favor of devoting all resources to building proven tanks like the Panther and Tiger II. Most Maus prototypes were blown up in the last weeks of the war as the Russians closed in on Meppen, although guns, turrets and hulls were found by Allied Intelligence officers abandoned and partially destroyed. According to some sources however, the two experimental Maus tanks were sent into action in the final days of the war, one at the approaches to OKH staff headquarters at Zossen, the other near the proving grounds at Kummersdorf. Design studies found at Krupp showed a version of the Maus carrying a 305mm breech-loading mortar, named 'Bear', and a giant 1500-ton vehicle with a 800mm gun as main armament plus two 150mm guns in auxiliary turrets on the rear quarters. This vehicle, put forward by two engineers named Grote and Hacker, was planned to be powered by four U-boat diesel engines!

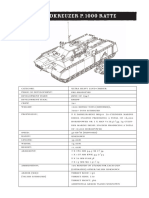

Land Cruiser P-1000 "Ratte

Technical Data Weight: Crew: Engine: Fuel Capacity: Speed: Range: Length: Width: Height: Armament: Ammo: 188,000kg (4,136,000 lbs)/206 tons 6 men Daimler-Benz MB 509 / 12-cylinder / 1080hp (V1) Daimler-Benz MB 517 Diesel / 12-cylinder / 1200hp (V2) 2650-2700 liters + 1500 liters in reserve tank 13-20km/h Road: 160-190km Cross-Country: 62km 10.09m (33.297 ft) 3.67m (12.111 ft) 3.63m (11.979 ft) 128mm KwK 44 L/55 & 75mm KwK 44 L/36.5 1 x 7.92mm MG34 128mm - 55-68 rounds 75mm - 200 rounds Turret Roof: 60/90 Gun Mantlet: 250/round Front Turret: 220-240/round Superstructure Roof: 50-100/9 Front Glacis Plate: 200/55 Hull Front: 200/35 Belly Plate Fore: 100/90 Side Turret: 200/30 Hull Side Upper: 180/0 Hull Side Lower: 100+80/0 Rear Turret: 200/15 Hull Rear Upper: 150/37 Hull Rear Lower: 150/30 Belly Plate Aft: 50/90

Armor (mm/angle):

Rear view of Maus

Completed Maus

Maus displayed in Russian Kubinka Museum outside Moscow

In order to transport the Maus, a special 14-axle railroad transport car (Verladewagon) was produced by Graz-Simmering-Pauker Works in Vienna

Possible Maus variant, the Zwilling, with dual 88 mm guns.

A report on the German Maus super-heavy tank, from the Intelligence Bulletin, March 1946. The German Mouse Super-Heavy Tank Became Hitler's White Elephant One of the subjects of liveliest controversy during the Allied invasion of France was the heavy tankthe 50-ton Pershing, the 62-ton Tiger, the 75-ton Royal Tiger. Were these worth their weight? Did they gain in protection and fire poweras much as they sacrificed in mobility? Adolf Hitler's mind was presumably made up on this point. A pet project of his, which few were aware of, appears to have been a superheavy tank that would have dwarfed even the Royal Tiger. Dubbed the Mouse, this behemoth of doubtful military value was to weigh 207 tons, combat loaded. Two were actually built, although they were never equipped with their armament.

German engineers, concerned over the effect of turns upon track performance, made this electricpowered, remote controlled, large-scale wooden replica. The Mouse is an amazing vehicle, with spectacular characteristics. The glacis plate up front is approximately 8 inches (200 mm) thick. Since it is sloped at 35 degrees to the vertical, the armor basis is therefore 14 inches. Side armor is 7 inches (180 mm) thick, with the rear protected by plates 6 1/4 inches (160 mm) thick. The front of the turret is protected by 9 1/2 inches (240 mm) of cast armor, while the 8inch (200 mm) thick turret sides and rear were sloped so as to give the effect of 9 inches (230 mm) of armor. ARMAMENT For the main armament, a pea-shooter like an 88-mm gun was ignored. Selected instead was the powerful 128-mm tank and antitank gun, which was later to be replaced by a 150-mm piece 38 calibers in length.

(The standard German medium field howitzer 15 cm s.F.H. 18 is only 29.5 calibers in length.) Instead of mounting a 7.9-mm machine gun coaxially, the Mouse was to have a 75-mm antitank gun 76 calibers in length next to the 128- or 150-mm gun. A machine cannon for antiaircraft was to be mounted in the turret roof, along with a smoke grenade projector. In size, the Mouse was considerably larger than any German tank. Its length of 33 feet made it nearly 50 percent longer than the Royal Tiger. Because of rail transport considerations. its width was kept to 12 feet (that of the Royal Tiger and Tiger). A 12-foot height made it a considerable target.

A head-on view of the MAUS model affords an idea of the formidable appearance of the original Maus. Note the exceptional width of the tracks. In order to reduce the ground pressure so that the tank could have some mobility, the tracks had to be made very wideall of 43.3 inches. With the tracks taking up over 7 of its 12 feet of width, the Mouse presents a very strange appearance indeed from either a front or rear view. With such a track width, and a ground contact of 19 feet 3 inches, the Mouse keeps its ground pressure down to about 20 pounds per square inchabout twice that of the original Tiger. POWER PLANTS Designing an engine sufficiently powerful to provide motive power for the mammoth fighting vehicle was a serious problem. Though the Germans tried two engines, both around 1,200 horsepower (as compared to the Royal Tiger's 590), neither could be expected to provide a speed of more than 10 to 12 miles an hour. The Mouse can, however, cross a 14-foot trench and climb a 2-foot 4-inch step. Whatever the military possibilities of the Mouse might be, it certainly gave designers space in which to run hog wild on various features which they had always been anxious to install in tanks. One of these gadgets was an auxiliary power plant. This plant permitted pressurizing of the crew compartment, which in turn meant better submersion qualities when fording, and good anti-gas protection. Auxiliary power also permitted heating and battery recharging.

One of the fancy installations was equipment designed for fording in water 45 feet deepa characteristic made necessary by weight limits of bridges. Besides sealing of hatches and vents, aided by pressurizing, submersion was to be made possible by the installation of a giant cylindrical chimney or trunk, so large that it could serve as a crew escape passage if need be. The tanks were intended to ford in pairs, one powering the electric transmission of the other by cable. The electric transmission was in itself an engineering experiment of some magnitude. This type of transmission had first been used on the big Elefant assault gun-tank destroyer in 1943, and was considered by some eminent German designers as the best type of transmissionif perfectedfor heavy tanks. Another interesting feature of the Mouse from the engineering point of view was the return from torsion bar suspensionsuch as was used in the Pz. Kpfw. III, the Panther, the Tiger, and the Royal Tigerto a spring suspension. An improved torsion bar design had been considered for the Mouse, but was abandoned in favor of a volute spring type suspension. WHY THE MOUSE? Just why the Germans wanted to try out such a monstrosity as the Mouse is a question to be answered by political and propaganda experts. Whereas such a heavy tank might conceivably have had some limited military usefulness in breakthrough operations, it was no project for Nazi Germany experimentation in 1943, 1944, and 1945. For not only did German authorities waste time of engineers and production facilities on the two test models, but they even went so far as to construct a special flat car for rail transport. The drawbacks inherent in such a heavy tank are patent. Weigh not only denies practically every bridge in existence to the Mouse, but it impedes rail movement unless railways are properly reinforced at bridges, culverts, and other weak points. Fording to 45-foot depths would have solved many of the stream-crossing problems in Europe, but it seems that the Mouse could actually cross in water no deeper than 26 feet. Though sitting in a rolling fortress, the six men of the Mouse crew are practically as blind as in any tank. Because of low speed and high silhouette their vehicle would be most vulnerable to hits. Since it is reasonable to suppose that heavily fortified, static positions suitable for attack by a Mouse would also be fitted with very heavy, high-velocity guns capable of antitank fire, the even occasional combat value of the Mouse comes into question. The German 128-mm Pak 44 (also known in modified forms as the 12.8 cm Pak 80) is reputed to be able to penetrate 7 inches of armor at 2,000 yards. Since the Germans actually had their Pak 44 in service in 1945, when the Mouse was not yet in the production stage, it would appear that the Germans had the antidote before the giant tanks were ready. Moreover, in the later days of the war, a rolling colossus like a Mouse would have been almost impossible to conceal, and would have fallen an easy prey to air power. The psychological factor thus appears to have played a large part in the demand for construction of the Mouse. The German Army would never have desired such a tank, especially in 1942 when its design was apparently initiated. On the other hand, it would have made lurid headlines and Sunday supplement copy in both Allied and German press circles. But whatever the public reaction might have been, it seems questionable that the Mouse could have exerted any psychological effect on Russian, British, or American front-line troops unless the Germans possessed almost overwhelming strength, as they did when they crushed the Maginot Line in 1940. In 1944-45 it would have been too easy a mark for Allied gun and planes the first instant it appeared. MICE OF THE FUTURE The appearance of such a vehicle in the opening phases of a future war is not to be entirely discounted. When Red Army armored units counterattacked German forces advancing northward toward Leningrad in 1941, the Soviets effected a substantial surprise and just missed obtaining a considerable victory by

throwing in for the first time heavy 46-ton KV tanks backed by 57-ton modified KV's mounting 152-mm tank guns in their turrets.

KV1 as Pz 756(r) The first days of a war are a time of uncertainty. This is a period when peacetime armies are proving themselves, when their personnel are still anxious to determine the validity of their matriel and tactical doctrines, when they are anxious to discover what the enemy is like. Rumors grow fast, and untried men are likely to be impressed with the mere report of the size and gun power of a superheavy tank. Officers and noncoms should therefore be aware of the possibility of encountering such colossal tanks. They should see that their men know the deficiencies and real purpose of outlandish vehicles of the class of the German Mouse, and that they do not attribute to these vehicles capabilities out of all proportion to their actual battle value.

KV 2 as Pz 754(r)

A39 Heavy Assault Tank Tortoise

E100 and E90 vs. Super Heavy Allied Tanks

Future designs

THE E100 The E 100 project was the Heereswaffenamt rival to the Maus, as there was considerable opposition to Porsche and his unconventional mechanical ideas. Under Heydekampf at the Panzer Commission (Porsche was removed as head of this commission) a long-term plan was drawn up to produce a rationalized series of Entwicklung-typen (development-types) or E series. This range of tanks were to use standardized parts and were to be built in classes of varying sizes to replace existing vehicles. The types had a designation with a number indicating their weight in tons: E 10, E 25, E 50 (Panther replacement), E 75 (Tiger replacement) and E 100. Of these, only the E 100 project was actually started, as an attempt to rival Porsche's work. When Porsche started work on the Maus, an initial order was placed with Henschel, builders of the Tiger II, for a much enlarged, super-heavy version of the Tiger II. This project was known as the Tiger-Maus or VK 7001 PzKpfw VII Lwe (Lion). The armament was to be the same 128mm gun as the Jagdtiger. With the Entwicklung-typen programme, the VK 7001 order was replaced by the E 100, with the same gun and turret layout as the Maus, except that a 150mm or 170mm gun was envisaged as the main weapon. Road wheels, sprockets and idlers were to be similar to those used on the Tiger II. Armored covers were proposed for the tracks, which were one meter wide. Construction of the E 100 prototype proceeded slowly at Henschel's test plant after Hitler's order to cease work on super-heavy tanks, and at the end of the war only the bare hull and suspension were completed.

Specifications for E-100 Weight: Crew: Engine: Fuel Capacity: Speed: Range: Length: Width: Height: 137,790kg (303,138 lbs)/151.569 tons 5-6 men Maybach HL 230 P30 / 12-cylinder / 700hp (prototype) Maybach HL 234 / 12-cylinder / 800hp (production) u/k 38-40km/h Road: 120km 10.27m (with the gun)/33.891 ft 8.70m (w/o the gun)/28.71 ft 4.48m (14.784 ft) 3.32m (battle tracks)/10.956 ft 3.29m (transport tracks)/10.857 ft 128mm KwK 44 L/55 & coaxial 75mm KwK 44 L/36.5 1 x 7.92mm MG34 (planned) 150mm KwK 44 L/38 & coaxial 75mm KwK 44 L/36.5 1 x 7.92mm MG34 (prototype) 170mm KwK 44 & coaxial 75mm KwK 44 L/36.5

Armament:

1/2 x 7.92mm MG34/42 (production) Ammo: u/k Front Turret: 240/round Front Hull: 150/40 Front Superstructure: 200/60 Side Turret: 200/30 Side Hull: 120/0 Side Superstructure: 60+120/20&0 Rear Turret: 200/7 Rear Hull: 150/30 Rear Superstructure: 150/30 Turret Top / Bottom: 40/90 Hull Top / Bottom: 80/90 SuperstructureTop / Bottom: 40/90 Gun Mantlet: 240/Saukopfblende

Armor (mm/angle):

The E-100 was originally designed as a Waffenamt alternative to the Porsche-designed super heavy Maus tank. It was authorized in June, 1943 and work in earnest continued until 1944 when Hitler officially ended development of super heavy tanks. After Hitler's announcement, only three Adler employees were allowed to continue assembly of the prototype, and the work was given lowest priority. Even with these handicaps, the three workers were able to virtually complete the prototype by war's end at a small Henschel facility near Paderborn. The prototype lacked only a turret (which was to be identical to the Maus turret save in armament). For its initial tests, a Tiger II Maybach HL230P30 engine had been fitted. This engine, of course, was far too weak to properly power the 140 ton E-100. The production engine was to be the Maybach HL234. The HL234 developed 800hp, which is only 100hp better than the HL230P30. Some sources indicate that a Daimler-Benz diesel which developed 1000hp would have ultimately been used. The Maus mounted the 12.8cm KwK 44 L/55 found in the Jagdtiger. Using the same turret, the E-100 was initially slated to use the 15cm KwK44 L38, but provision was made to eventually up-gun the vehicle with a 17cm KwK 44. The E-100 was very conventional in its architecture. The standard rear-engine / front-drive layout was maintained. The engine deck of the Tiger II was also carried over into this design (rather than the updated design of the E 50/75). The suspension was characteristic of the E-series, however, in that it was of the externally-mounted Belleville Washer type. While the engine-deck layout of the prototype was taken directly from the Tiger II, it is entirely possible that it would have been changed to match the E 50/75 had production of the E-series actually began to allow for maximum commonality of components. The armor on the E-100 was designed to withstand hits from just about any anti-tank round of the day. Armor on the turret ranged from 200mm on the sides and rear to 240mm on the front. The turret roof was protected by a seemingly paltry 40mm of armor. Unfortunately, the round shape of the turret front could have deflected shots downward into the top of the superstructure. Armor protection on the superstructure varied from 200mm on the front to a total of 180mm on the sides and 150mm on the rear. The top of the superstructure was protected by the same 40mm of armor found on the turret. The hull had 150mm of armor on the front and rear and 120mm on the sides behind the suspension. Protection on the bottom of the hull was good at 80mm.

E-100 and PzKpfw IV Given the armored protection of the E-100, most tanks would have needed a shot to deflect into the top of the superstructure from the turret front to knock it out. The vehicle would have, however, been highly vulnerable to air attack as the angles presented to dive bombers or fighter/bombers would have been protected to only 40mm. This protection is comparable to the Tiger II in the same areas.

How the E-100 was discovered in 1945 by Allied troops! Note the sheer size of the monster!

E-100 as discovered uncompleted in 1945

The E-100s giant tracks

The abandoned hull of the E-100

What might have been E50

PzKpfw E.100

Panther III

PANZERKAMPFWAGEN VII LWE (1941-1942) By Rob Arndt The development of this super-heavy tank started as early as 1941, when Krupp was performing studies of super-heavy Soviet tanks.

Early concept of the Lwe In November 1941, it was specified that the new heavy tank was to have 140mm front armor and 100mm side armor. The vehicle was to be operated by five men crew - three in the turret and two in the hull. This new Panzer was to have a maximum speed of some 44km/h being powered by a 1,000hp Daimler-Benz marine engine used in German S-Boots (motor torpedo boats). The main armament was to be mounted in the turret. The weight was to be up to 90 tons.

In the early months of 1942, Krupp was ordered to start the process of designing a new heavy tank designated PzKpfw VII Lwe (VK7201). Its design was based on a previous project by Krupp designated VK7001 (Tiger-Maus) and created in competition with Porsche's designs (including first Maus

designs).VK7001 was to be armed with either 150mm Kanone L/37 (or L/40) or 105mm KwK L/70 gun. Lwe was to utilize Tiger II's components in order to simplify the production and service.

1942 Leopard Design Designers planned to build two variants of this streamlined vehicle with rear mounted turret. The Leichte (Light) variant would have frontal armor protection of 100mm and it would weigh around 76 tons. The Schwere (Heavy) variant would have frontal armor protection of 120mm and it would weigh around 90 tons. Both variants would be armed with 105mm L/70 gun and coaxial machine gun. It is known that 90ton Schwere Lwe was to have its turret mounted centrally and in overall design resembled the future Tiger II. Variants of the Lwe were both to be operated by the crew of five. It was calculated that their maximum speed would range from 23km/h (Schwere) to 27km/h (Leichte). Adolf Hitler ordered that the design Leichte Lwe was to be dropped in favor of Schwere Lwe. The Lwe was to be redesigned in order to carry 150mm L/40 or 150mm L/37 (probably 150mm KwK 44 L/38) gun and its frontal armor protection was to be changed to 140mm. In order to improve its performance, 9001,000mm wide tracks were to be used and top speed was to be increased to 30km/h. In late 1942, this project was cancelled in favor of the Porsche development of the Maus. During the development of Tiger II, designers planned to build a redesigned version of the Lwe (as suggested by Oberst Fichtner), which would be armed with 88mm KwK L/71 gun and its frontal armor protection would be 140mm (as planned before). This re-designed Lwe would be able to travel at a maximum speed of 35km/h and it would weigh around 90 tons. It was to be powered by a Maybach HL 230 P 30, 12-cylinder engine producing 800hp. Lwe would be 7.74 meters long (with the gun), 3.83 meters wide and 3.08 meters high. Lwe would be operated by a crew of five. It was planned that the Lwe would eventually replace Tiger II. From February to May of 1942, six different designs were considered, all based on the requirements for Lwe. On March 6, 1942, the order for a heavier tank was placed and project Lwe was stopped in July 1942. The Lwe project never reached the prototype stage, but it paved the way for its successor's development - Porsches 188 ton Maus. Technical Data: Weight 90 tons [180,000 lbs] Crew 5 Men

Length 7.70 m [25.41 ft] Width 3.80 m [12.54 ft] Height 3.10 m [10.23 ft] Maximum Speed 30 km/h Tracks 900-1000mm [3.6-4.0 ft] Motor Maybach HL 230 P 30 Power 800 Hp Production: Production Status Project Production None Armament: Main Gun 88mm KwK L/71, 150mm KwK L/37 or 38 Armor: Hull and Turret Front 140 mm/5.6 inch Side 100 mm/4.0 inch

One of the first intelligence reports on the Tiger II, the new German heavy tank encountered in the fighting in Normandy, Tactical and Technical Trends, October, 1944. The odd name 'PanTiger' did not last long, and the Allies soon referred to the new tank as the Tiger II, King Tiger, or Royal Tiger. PANTIGER, A REDESIGNED TIGER NEWEST ENEMY HEAVY TANK A new 67-ton German heavy tank - referred to variously as Pantiger and Tiger II - has been employed against the Allies this summer in France. Actually a redesigned Tiger (Pz. Kpfw. VI), it mounts the 8.8-cm Kw. K. 43 gun. On the basis of a preliminary report, the general appearance of the new tank is that of a scaled-up Pz. Kpfw. V (Panther) on the wide Tiger tracks. It conforms to normal German tank practice insofar as the design, lay-out, welding, and interlocking of the main plates are concerned. All sides are sloping. The gun is larger than the Panther gun, and longer than the ordinary Tiger gun. Armor is also thicker than that on either the Panther or the Tiger. The turret is of new design, with bent side plates. In all respects the new tank is larger than the standard Tiger. Principal over-all dimensions of the redesigned Tiger are as follows: Length _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 23 ft. 10 in. Width _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 11 ft. 11 1/2 in. Height _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 10 ft. 2 in. Main armament is the 8.8-cm Kw. K. 43. It is equipped also with two machine guns (MG 34), one mounted coaxially in the turret and one mounted in the hull. Armor thicknesses of the new tank are as follows: Glacis plate _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 150-mm at 40 to 45. Hull side _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _80-mm vertical. Superstructure side _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 80-mm at 25.

Hull rear plates _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 80-mm at 25. (undercut). Superstructure top plates _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 42-mm horizontal. Turret front _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Approx. 80-mm (rounded). Turret side _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 80-mm at 25. Turret rear _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 80-mm at 25. Turret roof _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 42-mm horizontal; front and rear sloped at about 5 from horizontal. The suspension consists of front driving sprockets, rear idler, and independent torsion bar springing, with twin steel-rimmed rubber-cushioned disk bogie wheels on each of the nine axles on each side. The bogie wheels are interleaved, and there are no return rollers. Contact length of the track on the ground is about 160 inches.

Panzerkampfwagen VII 'Lwe'

Panzerkampfwagen VIII 'Maus'

Panzerkampfwagen IX

Panzer IX and Panzer X were meant as disinformation designs published in 1944 in Signal magazine to fool the Allies, but by the end of the war similar rounded German tank designs were being evaluated. PzKpfw X was to be wider but lower than Maus and was to be armed with the German 88mm or even 128mm gun. Both designs were very advanced and modern including many features which can be found in modern tanks of today.

"PzKpfw VII (schwere) Lwe". Germany, 1942

LEOPARD

Light version

Heavy version

1000-ton Panzer By Gary Zimmer In June 1942 Hitler and Krupp discussed the feasibility of a one thousand ton super heavy tank. Unusually, Dr. Ferdinand Porsche does not seem to be involved, although this project would be right up his alley. As of December 29, 1942 some preliminary drawings at least had been done. By then the machine had been named 'Ratte' (Rat). If built, P.1000 would have dwarfed its little cousin, Maus. Intended to be 35m long, 14m wide and 11m high, and armed with an ex-Kriegsmarine turret with two 28cm SchiffsKanone C/28. In other words a triple turret similar to those used on the Graf Spee class, but without the center gun. Each gun weighed 48.2 tons and had a barrel length of nearly 15m. Projectiles were 1.2m long, Panzersprenggranate (armor piercing) rounds weighing 330 kg each and containing 8.1kg of explosive, or 315kg Sprenggranate (high explosive) rounds containing 17.1kg of explosive. The maximum range of these guns was 42.5km (26 miles). Some sort of secondary anti-aircraft armament in the form of 2cm Flak guns was planned. One feature of the design, as indicated on the drawing, was the use of triple tracks, each individual track being 1.2m wide. Power was to have been eight Daimler marine engines (presumably E-boat), developed to produce a total 16,000 hp. There are some anomalies in the design of Ratte, as depicted. The amount of track in contact with the ground is inconsistent with the weight of 1000 tons, either it will have a ridiculously low ground pressure, meaning that all that track is not necessary; or it will be heavier than 1000 tons. If we imagine the center hull between the tracks to be an armored box, without worrying yet about the belly or roof, and 200mm thick (and that is a bit light by battleship standards), it works out to be about 730 tons on its own. That doesn't leave a whole lot for suspension, tracks, engines, belly and deck armor. The pair of guns on their own would be another 100 tons, and we can assume that the turret would have to be armored to at least 250mm. If we include the barbette, the turret should account for at least 380 tons, not counting guns, gun mounts and shell hoists. The ammunition stowage is anybody's guess, but bear in mind every three rounds adds another ton to the total weight. If Ratte was built, it would probably end up closer to 2000 tons. Landkreuzer P1000 'Ratte' The world will probably never see an armored land vehicle on the scale of the Ratte. Tellingly, Germans didnt even refer to it as a tank: they called it a land cruiser. The Ratte was so large its dimensions had more in common with a naval vessel than a tank. It had the crew compliment of at least four heavy tanks, armament usually seen mounted on heavy cruisers like the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and enough antiaircraft weaponry to ward off waves of attacking fighter-bomber. It was 35 meters long, as tall as some

church steeples, and so wide that maneuvering in an urban area would have been either impossible or apocalyptic. The Ratte was so heavy it would have shattered and churned pavement like a plow through sod and collapsed all but a handful of bridges in Germany. The Rattes much smaller cousin, the Maus, turned out to be a ruinous waste of resources for very limited applications in combat. Had the Rattes development progressed even a fraction as far as the Maus it would have devastated Germany. The Ratte was so large that it would have required naval-scale manufacturing with months of skilled laborers time involved in the construction of each individual tank. Just building and assembling its components would have required transportation and handling equipment usually relegated to a shipyard. It is probably to the detriment of the world that the Ratte project was cancelled. It would have been cool just to see one of these hideous machines built and, more importantly, it would have taken the place of perhaps fifty or a hundred more useful tanks like the Panther or Panzer IV. The Ratte would have meant an earlier end to hostilities in Europe and it would have provided a damn hot ticket at a museum in the United States or the Soviet Union. Development The development history of the Ratte originates with a 1941 strategic study of Soviet heavy tanks conducted by Krupp. This study also gave birth to the Rattes smaller and more practical relative: the Maus. From the start the Maus was envisioned as an even larger and more formidable version of a heavy tank, while the Ratte was to be a class of vehicle unto itself. This 1941 study produced a suggestion from director of engineering Grote who worked for the U-boat arm of the Ministry of Armaments. In June of 1942, Grote proposed a 1000-ton tank that he termed a Landkreuzer equipped with naval armament and armored so heavily that only similar naval armaments could hope to touch it. To compensate for the immense weight of the vehicle the Ratte would have sported three 1.2 meter wide tread-assemblies on each side totaling a tread width of 7.2 meters. This helped with the stability and weight distribution of the Ratte but its sheer mass would have destroyed pavement and prevented bridge travel. Fortunately, the height of the Ratte and its nearly 2 meters of ground clearance would have allowed it to ford many rivers with ease. Hitler became enamored with the idea of a truly super tank and ordered Krupp to set to work developing the Ratte. While development of the Ratte does not seem to have progressed very far some sources believe that a turret was completed for the Ratte and then used as a fixed gun emplacement in Norway. Several such emplacements survived the war, many mounting turrets from broken-up vessels very similar to the turret intended for the Ratte. However, despite references to a Ratte turret being used as a fixed emplacement there is no evidence that it ever existed. The Gneisenau was broken up in 1944 and its turrets were used as emplacements near Rotterdam in Holland. Similar turrets were used near Trondheim in Norway which was the supposed location of the Ratte turret.

Battery rland - Norway [Originally the C turret on the Gneisenau]

Development of the Ratte was completely cancelled in 1943 by the dangerously wise German Minister of Armaments, Albert Speer. Speer exhibited an uncanny ability to cancel the more moronic and wasteful of Hitlers pet projects and focus German resources on proven weapon systems. Technical Mumbo Jumbo There were two proposed power plants for the P. 1000 Ratte. One concept was powered by two MAN V12Z32/44 24-cylinder diesel engines similar to those used on German submarines. This double engine design produced a Herculean 17,000 horsepower. These were the engines used to derive the 44kp/h maximum speed of the Ratte by the Germans. The more likely engine was the Daimler-Benz MB501. This 20-cylinder marine diesel engine was identical to that used on the German fast torpedo boats or S-boots. Linking eight of these engines would have theoretically produced 16,000 horsepower. Given that the MB501 was a more proven, inexpensive, and easier to manage engine it seems likely this eight-engine design would have appeared in the Ratte prototype. The primary armament of the Ratte was two 280mm SK C/34 naval guns mounted in a modified naval heavy cruiser turret fitting two guns instead of three. The SK C/34 was a devastating piece of artillery capable of penetrating more than 450mm of armor at its maximum effective direct-fire range of roughly five kilometers. The guns could also be elevated up to 40 degrees to achieve a range of 40 kilometers. Armor-piercing shells and two types of high explosive shells were available for these naval guns. One difficulty facing the 280mm dual battery would have been the Rattes inability to sufficiently depress its weapons to fire at nearby targets. Accompanying vehicles would have likely accomplished this task.

Jagdtiger Additional armament was a 128mm anti-tank gun like that mounted on the Jagdtiger or Maus, two 15mm heavy machineguns and eight 20mm anti-aircraft guns, probably with at least four of them as a quad mount. The 128mm anti-tank guns location on the Ratte is a point of contention among historians. Most believe it would have been mounted within the primary turret, though some think a smaller secondary turret would have been mounted at the rear of the Ratte near the engine decking. The rear turret makes more sense logistically, but the surface area of engine decking at the rear of the Ratte might have made this unrealistic. A third option would have been a hull-mounted version of the 128mm gun similar to that

seen on the Jagdtiger. This would have at least been able to engage nearer targets than either of the other options. Additional armament would have been spread on and throughout the Ratte. The heavy-machineguns and some of the 20mm guns would have probably been mounted inside ball mounts in the hull of the Ratte. A quad 20mm flak gun could have been mounted on the extremely large top surface of the turret and additional 20mm guns mounted on the top hull at the rear of the Ratte. If they were willing to put up with the exhaust fumes, an entire platoon of Panzergrenadiers could have sat atop the rear hull of the Maus. While the Ratte was supposedly a 1000-ton vehicle this number was an almost mystically optimistic figure, much like the 100-ton weight intended for the Maus. The turret alone for the Ratte would have weighed more than 600 metric tons. The actual combat-loaded weight of the Ratte would have been closer to 1,800 tons. The speed, range, and longevity of the engines and transmission would have suffered accordingly. Variants The Ratte was a paper Panzer and as such the only real variants were the two choices of engines. Analysis The Ratte was a very problematic vehicle and the size of the Ratte was responsible for most of the issues it would have encountered on a hypothetical battlefield. A Ratte on the move would have been relegated to fields and countryside because of its road-destroying weight. Without bridges as a river-crossing option, the Ratte would have been unable to cross flooded or deep rivers and scouting parties might have wasted lengthy periods and squandered lives finding a crossing point. Gunners on a Ratte would have found it awkward to engage targets from close or medium range with even a hull-mounted 128mm gun. Concealing the Ratte from aircraft would have required a blimp hangar or some sort of bizarre camouflage that would make it resemble a building. Such camouflage is feasible, if comical, but would have been useless the first time ground units spotted the Ratte. From that point on the Ratte would have been constantly harassed by fighter-bombers. Even if the Rattes 20mm AA guns had managed to drive these off, the Ratte was such an enormous target that high-altitude bombers could have been employed to attack it. Not everything was bad about the Ratte. Infantry would have been less of a risk than with the Maus because of the number of point defense weapons and the space for infantry to ride on the vehicles hull. The Ratte would have likely served as the cornerstone of a unit of traditional military vehicles and these would have assisted in defending it from enemy tanks and aircraft. Enemy armor posed almost no conceivable threat to the Ratte. They might have destroyed things like the AA guns on the turret or damaged radio antennae or weapon optics, but beyond minor damage enemy tanks were toys next to this mammoth vehicle. Enemy artillery was slightly more threatening and became downright dangerous if the Ratte made the mistake of straying within range of naval bombardment. The greatest strength of the Ratte would have been its ability to single-handedly halt a major enemy offensive. It would have been slow and poor on the attack but the sight of a Ratte looming out of fog on a battlefield would have almost immediately scattered enemy ground forces. If they didnt flee right away they would have once they realized their weapons were nearly useless against it. Make no mistake, the astronomical cost of building a Ratte would not have been offset by its strengths. Once deployed and used in combat, it was just a matter of time before enemy aircraft destroyed it. With such poor speed and the limitations of the terrain the Ratte would not have enjoyed the same advantages of a wide open sea as its naval counterparts. The Ratte could have turned the tide of a single battle at the cost of a campaign.

The 80cm 'Gustav' in Action The largest gun ever built had an operational career of 13 days, during which a total of 48 shells were fired in anger. It took 25 trainloads of equipment, 2000 men and up to six weeks to assemble. It seems unlikely that such a weapon will ever be seen again. The 80-cm K (E), for all its size and weight, to say nothing of its 'overkill' firepower, went into action on only one occasion. It was originally intended to smash through the extensive Maginot Line forts but when the campaign in the West took place in 1940 the 80-cm K (E) was still in the Krupp workshops at Essen and, in any event, the German army bypassed the Maginot Line altogether. Thus when the 80-cm equipment had completed its gun proofing trials at Hillersleben and its service acceptance trials at Rugenwalde there was nothing for the gun and its crew to do. To justify the labour and effort of getting the huge gun and its entourage into action, the potential target had to justify all the bother involved, and there were no really large fortification lines left in Europe for the gun to tackle. The two major fortification systems, the Sudetenland defenses and the Maginot Line, were both in German hands and it seemed that the 80-cm K (E), or 'schwere Gustav' (heavy Gustav) as it became known, was redundant even before it had fired an aggressive shot During early 1941 one potential target appeared on the planner's drawing boards and that was Gibraltar. It was planned to assault this isolated fortress at the mouth of the Mediterranean to deny the inland sea to the Allies but as Spain was neutral, permission had to be obtained from General Franco to allow German troops to travel through Spain to make the attack. Operational planning for the assault (named Operation 'Felix') got to the stage at which German parachute and glider troops were actively training for the assault before a meeting between Hitler and Franco showed that the wily Spanish dictator was not going to allow himself or his country to become mixed up in a major European conflict, Thus another potential target for the 'schwere Gustav' came and went. The invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation 'Barbarossa') took place during the second half of 1941 without any assistance from the 80-cm K (E), but by early 1942 the advances of the German army were so rapid and deep that they were on the approaches to the Crimea. Ahead of them lay the naval base of Sevastopol, which was potentially a useful supply port and base for the southern German armies. The need for such a supply base was not very pressing, but what attracted the German operational planners was that Sevastopol was a heavily-fortified port. Around the perimeter of the city was a long chain of fortifications; some of them dating back to the days before the Crimean War of 1854-6 but others more modern, and near the sea coasts there were numerous heavy coastal batteries. The place looked ideal for an investment and siege in the old manner, to be followed up by a huge assault which would demonstrate to the world the power of the German army. Soon the relatively light forces that advanced into the Crimea were supplemented by more and more troops and the German planners started to scour Europe for heavy guns to form an old-fashioned siege train.

Karl-Gert For centuries it had been the task of the siege train to bombard a besieged fortress into submission or else open a breach for attacking troops to storm. The Germans decided to repeat this performance on a massive scale. From all corners of Europe the German army assembled a massive gun park of all types of artillery from small-caliber field guns up to pre-World War I large-caliber howitzers. Some were German in origin but others were old captured weapons, and to these were added the modern embellishments of artillery rockets and super-heavy artillery. Into this category came the 60-cm (23.6-in) mobile mortars known as the Karl-Gert, and it was realized that at last the propaganda coup could be topped by the first operational use of 'schwere Gustav'. Accordingly the 80-cm K (E) trundled to the Crimea on specially re-laid track. Well ahead of its progress a small army of laborers started to prepare the gun's chosen firing position at Bakhchisaray, a small village outside Sevastopol. Well over 1,500 men under the control of a German army engineer unit dug through a small knoll to form a wide railway cutting on an arc of double track, and the sides of the cutting were raised to provide cover and protection for the gun. On the approaches railway troops labored to re-lay track and strengthen possible trouble points against the passing of the 'schwere Gustav'. Work on the eventual firing site reached the point where the area behind the curve of firing tracks resembled a small marshaling yard over 1. 2 km (0. 75 miles) long. It resembled a marshaling yard, and that was exactly what it was. In the area the 25 separate loads that formed the gun and its carriage had to be assembled and pushed and pulled into the right position and order. Farther to the rear were the accommodation areas where the numerous men of the gun crew lived and prepared for their task The manpower involved in assembling 'Schwere Gustav' was large. Each of the 80-cm K(E)s had a complete detachment of no less than 1,420 men under the command of a full colonel. He had his own headquarters and planning staff, and there was the main gun crew which numbered about 500, most of whom were involved with the complicated ammunition care and handling. Once in action these 500 would remain with the gun, but the rest of the gun's manpower was made up from various units including an intelligence section to determine what targets to engage. Quite a number of troops were involved in the two light anti-aircraft defense battalions that always accompanied the gun when it travelled and also supplied manpower for some assembly tasks. Once the gun was in position these AA battalions warded off unwanted aerial intruders. Two guard companies constantly patrolled the perimeter of the gun position (at one time these companies were Romanian), and at all times there was a small group of civilian technicians

from Krupp who dealt with the technical aspects of their monster charge and advised the soldiers. Railway troops and the usual administrative personnel added to the manpower total. Even using this small army of men it took between three and six weeks to assemble the gun, even using the two 10-tonne cranes that had been designed especially for the task. Just getting the right subassembly load into position at the right time was a masterpiece of railway marshaling and planning, but eventually it was all sorted out and by early June 1942, 'schwere Gustav' was ready, along with the rest of the siege train with all their cumbersome carriages and ammunition emplaced ready to hand. Firing commenced on June 5, 1942. 'Schwere Gustav' was but one voice in a huge choir that heralded one of the largest and heaviest artillery bombardments of all time. By the time Sevastopol fell early in July 1942 it was calculated that no fewer than 562,944 artillery projectiles had fallen on the port, the bulk of them from heavy-caliber guns and howitzers, and this total does not include the noisy storms of artillery rockets and the extra weight of the infantry's own unit artillery. How the civilians of Sevastopol survived it all can now be explained quite easily. They simply went underground. The city knew the bombardment was coming, for not only had their own party and other authorities told them what to expect, but the Germans constantly assailed them with radio broadcasts and other propaganda as to the wrath that was to befall them. By the time the real bombardment started they had already dug deep shelters both underground and in the walls of quarries and hillsides, and there they lived and remained for weeks, A surprising number survived it all. 'Schwere Gustav' was not used against civilian targets. Its first targets were some coastal batteries that were engaged at a range of about 25,000 m (27,340 yards), and all shots were observed by a special Luftwaffe flight of Fieseler Fi-156 Storchs assigned to the gun. Eight shots were all that were required to demolish these targets, and later the same day a further six shots were fired at the concrete work known as Fort Stalin. By the end of the day that too was a ruin and preparations were made for the following day. It might be thought that 14 rounds in a day was slow going, but in fact it was good going for a gun with a caliber of 80 cm (31.5 in). At best the firing rate was one round every 15 minutes, and more often the interval was longer. The preparation of each shell and charge was considerable and involved several stages including taking the temperature of each charge, accurately computing the air temperature and wind currents at altitude, and getting the shell and the charge to the breech. Projectile and charge then had to be rammed accurately, and the whole barrel had to be elevated to the correct angle. It all took time. 'Schwere Gustav' was in action again on 6 June, initially against Fort Molotov. Seven shells demolished that structure and then it was the turn of a target known as the White Cliff, This was the aiming point for an underground ammunition magazine under Severnaya Bay and so placed by the Soviets as to be invulnerable to conventional weapons. It was not invulnerable to the 80-cm K (E) for nine projectiles bored the way down through the sea, through over 30 m (100 ft) of sea bottom and then exploded inside the magazine. By the time 'schwere Gustav' had fired its ninth shot the magazine was a wreck, and to cap it all, a small sailing ship had been sunk in the process. The next day was 7 June, and it was the turn of a target known to the Germans as the Sdwestspitze, an outlying fortification that was to be the subject of an infantry attack. After seven shots the target was ready for the attentions of the infantry and the gun crews were then able to turn their attentions to some gun maintenance and a short period of relative rest until 11 June. On that day Fort Siberia was the recipient of a further five shells, and then came another lull for the gun crews until 17 June, when they fired their last five operational shells against Fort Maxim Gorki and its attendant coastal battery. Then it was all over for 'schwere Gustav'. Once Sevastopol had fallen on 1 July, the German siege train was dispersed all over Europe once more, and 'schwere Gustav' was taken apart and dragged back to Germany, where its barrel was changed. Including the 48 operational shells fired against the Crimean targets, 'schwere Gustav' had fired about 300 rounds in all, including proofing, training and demonstration rounds. The old barrel went back to Essen for relining. There was nothing more for 'schwere Gustav' to do, It spent some time on the Rugenwalde ranges firing the odd demonstration projectile and being used for the development of some long-range concretepiercing projectiles, and at one point there was talk of replacing the 80-cm (31.5-in) barrel with a 52-cm

(20.5-in) barrel to provide the weapon with more range. That project came to nothing, as did a project to place the 80-cm (31.5-in) barrel on a tracked self-propelled chassis for street fighting. Considerable planning was spent on this outlandish idea before it was terminated, though the idea was no more impractical than the whole 80-cm K (E) project, which had absorbed immense manpower and facilities of all kinds, all to fire 48 rounds at antiquated Crimean fortifications. By May 1945 'schwere Gustav' was scattered all over central Europe. The carefully-planned trains had been attacked constantly by Allied aircraft and what parts were still in one piece were wrecked by their crews and left for the Allies' wonderment. Today all that is left of 'schwere Gustav' and 'Dora' are a few inert projectiles in museums. A Czech book seems to suggest that it was planned to move it to the Channel for bombardment of England, and there are drawings of the proposed tunnel. 1500-ton Self-Propelled 80cm Gun By Gary Zimmer In a paperback titled Tanks of the Axis Powers published over 20 years ago there is a brief mention of some of Germany's armored follies. It mentions a 1500 ton super heavy tank, cased in 250mm of armor, armed with an 80cm gun and two 15cm weapons, and powered by four U-boat diesels. Although there was no illustration I have always been curious as to what this 1500 tonner would look like.

"Heavy Gustav " or "Dora"

However we do know something about the proposed main weapon, the 80cm. Although not the largest caliber gun ever made, or the longest ranged, the 80cm railway gun 'Dora' was the biggest. As far as we know it was used only sparingly, to shell Sevastopol in the Crimea, and later Warsaw. Too large to be transported whole, Dora required several trains to transport it. Before assembly could begin, and this took several weeks to accomplish, a second track had to be laid at the chosen firing site. Movable straddle cranes also had to be assembled, these were on their own additional rails. The two 20 axle halves of the chassis were shunted onto the double tracks side by side, and coupled together. Only then could the cranes start putting the really big bits on. Once assembled Dora must have been an awesome sight, all one thousand three hundred and fifty tons of it. The barrel alone weighed 100 tons, the breech was also another 100 tons. It could fling a 7 ton shell about 45 km. As a piece of static siege artillery there was no question of its effect, but even its creators, Krupp, admitted while it was a valuable research tool, as a practical weapon of war it was useless. Which brings us to the 1500 tonner, aptly named 'Monster' by armaments minister Albert Speer. It may have been an attempt to make some use of Dora, or simply an extension of a policy to self-propel all heavy artillery, but someone got the idea of putting Dora on tracks.

Alleged wartime sketch of the "Monster"

The wartime sketch (provided courtesy Karl Horvat, an Australian researcher) is all we have, but it allows us to deduce a few things. One reason why you can't simply scale up an existing tank design is ground pressure. If you know the mass and dimensions (i.e. area of track in contact with the ground) of a vehicle, it is quite easy to work out ground pressure. Put simply, weight will be roughly proportional to the volume or the cube of the dimensions, while the area of track in contact with the ground will be proportional to the square of dimensions. If we double the size of a tank, we get eight times the weight but only four times the track area, thus twice the ground pressure. (There's also twice the stress in suspensions, axles and everything else, it's why elephants have thicker legs than flamingos.) A very light tracked vehicle, such as a Bren carrier, will have what appears to be ridiculously narrow tracks. As a vehicle gets heavier, the proportion of its width covered by track increases. A Centurion has about 40% of its width as track, while for the 188 ton Maus tank, the figure was about 66% or two thirds. In fact the most striking thing about Maus is this proportion of track width to overall width. Assuming a pressure of 1.2 kg per sq cm for this 1500 tonner, that's about midway between that of a Centurion and a Maus, and seems a realistic place to start. Working backwards, we can use ground pressure and weight (1500 tons, or thereabouts) to find how much contact area it needs. Track width appears to be around 80% of the width, giving tracks of 2.4m width (each) for an overall width of 6m. The illustration appears to be about 6m wide, as is the gun on its rail mount. If we stick to an assumed six meter width, close to an upper limit if we ever consider movement by road, this behemoth thus requires 27m of track on the ground. There's only one problem with this, it won't turn. The shorter a tracked vehicle is, that is track length on the ground, the less resistance there is to turning. Also, the wider it is, the outside track is able to generate a greater turning moment, and overcome the resistance of both tracks to being pushed sideways. A governing aspect of tracked vehicle design is the ratio of the distance between track centers, and track contact length. Typically, this is about 2:1 for most vehicles. The 1500 tonner has a length/width ratio of about 7.5 to 1, and this is horrific. The way out of this is chassis articulation. By using four track units, each 14m long, and allowing each pair to be turned independently, it might just work. Having four track units ties in nicely with the four U-boat diesels. All the Porsche heavy tanks were electric drive, and it seems hard to imagine anything else for a machine this size. In a U-boat, the diesels drove dual purpose electric motor-generators, but on the 1500 tonner these would function as generators only. It seems logical that each diesel would have its own generator. These four generators would each run an electric motor in each of the four track units. Of course the diesels and generators could be anywhere in the vehicle, as no mechanical drive to the tracks would be required. The other pieces of information are harder to fit into the picture. Just where the two turrets, each with a 15cm gun, would fit I have no idea. If the layout of Dora is preserved, as the illustration seems to indicate, there appears to be no place for them. Also, having these turrets side by side, as Axis suggests, implies a much greater width than 6m if these turrets are not to foul. More puzzling still is the 25cm of frontal armor. The illustration shows that the loading decks, and of course the crew doing the loading, had no protection at all, nor would they need any being many miles from whatever they were shooting at. Having this extent of armor is only required if the machine is going to be used as a direct fire weapon, in other words as a tank and not a piece of selfpropelled artillery. It also appears that the shell hoists are retained, as on the rail gun. While having no on-board stowage of 80cm rounds is not an issue for SP artillery, it would be an absolute must for a 'tank'. Dora was supplied with 80cm rounds from the rail lines it sat upon, but this would not be any use to an SP operating away from any railhead. I imagine that ammunition vehicles would be required to deliver one round at a time to the hoists, they could possibly be similar to the Panzer IV carriers used with the Karl Mrsers. Apart from these carriers there would probably be a whole retinue of vehicles accompanying this giant machine; fire control and signals vehicles, a flak unit, the cook's truck, and so on.

Munitionsschlepper Panzer IV E-D We can only speculate how this machine might be moved. As with Dora, it could conceivably be transported by rail in pieces, but once assembled and moving under its own power beyond the rail network the fun would really start. As with all oversize vehicles, the planned route would need to be carefully surveyed. It would occupy the entire width of a road on its own, and travelling through any town en route would no doubt lead to a fair bit of urban renewal. Rivers would be less of a problem, as the machine's great height would permit fairly deep fording. However the greatest problem would be the high center of gravity due to the mass of barrel, breech, recoil system so high up, and sideslope of the ground would be the main restriction to travel, lest the vehicle keel over. As with other large land vehicles, there is a distinction between 'movable' and 'mobile'.

Rumor has it, this massive war-machine, dubbed the "Siege Bot" in Western intelligence circles, was built by the Iraqi regime under Saddam Hussein. The huge gun tube launched rocket-assisted howitzer rounds, and was intended to crack Iranian fortifications during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s. The Siege Bot vanished soon after the first Gulf War, having never fired on Allied troops. The United States denies having it.. It is reminiscent of the German assault gun Panzermrser Sturmtiger of 1944... Sturmmrser Tiger Type: Gigantic Rocket-Assisted Mortar Tank Specific Features: One of the most fearsome and effective German tanks of World War II was the Panzer Mk VI, or Tiger as it was better known. The Tiger mounted a long-barreled 88mm gun specially designed for it, unlike the later King Tiger and Jagdpanther which mounted modified full-size versions of the 88mm anti-tank gun. The Surmmrser Tiger, or Sturm Tiger, was based on the effective Tiger chassis but replaced the turret and 88mm armament with an enclosed superstructure and a massive 380mm rocketassisted mortar. The rocket activated shortly after firing and exhaust often backwashed down the stubby barrel of the Sturm Tiger. To counteract this potentially catastrophic effect the gun barrel had a ring of gas vents so that exhaust would vent outwards from the barrel.

The projectile, larger than most naval artillery, was capable of leveling a building in a single shot or penetrating through 2 and a half meters of reinforced concrete. The Sturm Tiger had a surprisingly large internal magazine given the size of the rockets, carrying 15 in total. For replenishing the magazine a special hatch was built into the roof of the superstructure and a loading arm and pulley system was attached to the back. This system allowed the crew to stand outside the tank and "hand" shells in. When the mortar was utilized it was almost always fired over a "flat" trajectory, meaning that unlike conventional mortars this one was also intended to be fired straight at the target and not lobbed in an arc.

History: Proposed in early August of 1943 as the Germans were once again mounting an increasingly desperate summer offensive against the Soviets, the Sturm Tiger was championed by Panzer Leader Heinz Guderian. He clearly saw the limitations of even heavy tanks when it came to urban fighting and wanted a weapon that could roll in to support the infantry and route the enemy from the toughest positions. The armament was derived from a secret project of the Navy to develop a means for submarines to bombard shore positions. The Kriegsmarine abandoned this project but it proved perfectly suited for the Sturm Tiger and was adopted with modifications. Unfortunately for the Germans, by the time the first of only 18 Sturm Tigers had rolled out of the Alkett plant in Berlin-Spandau a slow-moving anti-bunker tank was of dubious value. Despite this the Sturm Tiger performed well, proving adequate at anti-tank and infantry engagements in defense of the rapidly collapsing Reich.

Land Cruisers P-1000, P-1500 "Ratte"

A size comparative between the Panzer V [Panther] and the P-1000 [Ratte] The protruding barrels in the latter are 8x37mm Flak guns On June 23, 1942, Dir. Dip. Ing. Grote (along with Dr.Hacker) from the Ministry of Armament, who was responsible for the production of U-Boote suggested the development of a tank with a weight of 1,000 tons. Hitler himself expressed interest in this project and allowed Krupp to go ahead with it. The project was designated as the Krupp P.1000 (Ratte - Rat). This behemoth "land cruiser" would be 35 meters long, 14 meters wide and 11 meters high. P.1000 would be equipped with 3.6 meters wide tracks per side made of three 1.2 meters tracks, similar to those used in excavators working in coalmines. It was planned to power P.1000 with two MAN V12Z32/44 24 cylinder Diesel marine engines with total power of 17,000hp (2 x 8,500hp) or with eight Daimler-Benz MB501 20 cylinder Diesel marine engines with total power of 16,000hp (8 x 2,000hp). According to the calculations, this would allow the P.1000 to travel at maximum speed of 40 km/h. P.1000 would be armed with a variety of weapons such as: two 280mm gun (naval gun used on Scharnhorst and Gneisenau warships), single 128mm gun, eight 20mm Flak 38 anti-aircraft guns and two 15mm Mauser MG 151/15 guns.

P.1500 Monster

The Landkreuzer P. 1500 Monster was a pre-prototype ultraheavy tank meant as a mobile platform for the Krupp 800mm Schwerer Gustav artillery piece, in fact, a mobile grand cannon. If completed it would have easily surpassed the Panzer VIII Maus, and even the extremely large Landkreuzer P. 1000 Ratte in size. It would have been 42 m (138 ft) long, would have weighed 2500 tonnes, with a 250 mm hull front armor, 4 MAN U-boat (submarine) diesel engines, [though it would only have enough power to reach up to speeds of 10-15 kph] and an operating crew of over 100 men. The main armament would have been an 800 mm Dora/Schwerer Gustav K (E) railway gun 10 times bigger in diameter than modern tank cannons, and a secondary armament of two 150 mm SFH 18/1 L/30 howitzers and multiple 15 mm MG 151/15 machine guns. In early 1943, Armaments Minister Albert Speer cancelled both projects. The P.1000 turret allegedly ended up at a coastal defense battery rland near Trondheim, Norway. Prior to both the P.1000 and P.1500, in 1939, Krupp began working on other similar projects for a projected series of self-propelled coastal guns for the Kriegsmarine. The series was to include fourteen different platforms designated from R1 to R14. Armament was to range from 150mm to 380mm and they were to be mounted on fully traversable turntables on tracked carriages. One of the designs was the R2 coastal gun armed with a 280mm gun. The series never left the drawing boards for obvious reasons.

Die Glocke (German for "The Bell") is the name of a purported top secret Nazi scientific technological device. The only source for this is the books of Polish aerospace defense journalist and military historian Igor Witkowski, which claims it to be a secret weapon, or Wunderwaffe. The topic has been popularized by Nick Cook, Joseph P. Farrell and conspiracy theory websites, associating it with Nazi occultism and antigravity or free energy research. The device was first claimed to exist by Igor Witkowski, in his Polish language book Prawda O Wunderwaffe (2000, reprinted in German as Die Wahrheit ber die Wunderwaffe), in which he refers to it as "The Nazi-Bell". Little was known or reported on regarding the device until it was popularized in the English-speaking Western world by journalist, author, and former British aviation editor for Jane's Information Group, Nick Cook, in his book The Hunt for Zero Point. Interest grew, and Witkowski's book was translated into English in 2003 by Bruce Wenham as The Truth about the Wunderwaffe. Further speculation about the device has appeared in books by the American fringe authors Joseph P. Farrell, Jim Marrs, and Henry Stevens. "The Bell" has become something of a legend among believers in perpetual motion machines, anti-gravity devices, reality shifting, reanimation, and time-space manipulation. The Bell is said be an experiment carried out by Third Reich SS scientists working in the German facility Der Riese (The Giant) near Wenceslaus mine. The mine is located 50 kilometers away from Breslau a little north village of Ludwikowice Kodzkie (formerly known as Ludwigsdorf) close to Czech border. Cook and Witkowski visited the site for the UK Channel 4 documentary UFOs: the Hidden Evidence (aka An Alien History of Planet Earth).

The device is described as metallic, approximately 9 feet wide and 12 to 15 feet high with a shape similar to a bell. It contained two counter-rotating cylinders filled with a substance similar to Mercury that glowed violet when activated, known only as Xerum 525 it has been speculated to be Red mercury. When active, The Bell would emit strong radiation, which led to the death of several scientists and various plant and animal test subjects. According to Igor Witkowski, the Polish aerospace historian who researched this craft for 20 years and was interviewed for the Discovery Channel documentary Nazi UFO Conspiracy, "...The external appearance... was such that it was [a] ceramic cover, bell shaped, which housed a kind of core or axis, around which rotated two cylinders, around the axis in opposite rotation. And after connecting to high-voltage current, the cylinders start spinning in opposite directions... Everything suggests.. it could have been a way to master gravity." The Bell was considered so important to the Nazis that they killed 60 scientists that worked on the project and buried them in a mass grave and the only reason we know about the Bell is that the SS General that was tasked with the murders, Jakob Sporrenberg, was tried after the war by a Polish War Crimes court for murdering his own people on what subsequently became Polish soil. So it's his Affidavit that gives us the story of the Bell. What might have happened to The Bell, had it existed, were it to have been evacuated out of Germany is unknown, however there has been some speculation: Witkowski speculated that it ended up in a Nazifriendly South American country, Cook speculated that it ended up in the United States as part of a deal made with SS General Hans Kammler and Farrell speculated that it did not reach the United States until it was recovered in the Kecksburg UFO incident. While the purpose of The Bell is unknown, there is a wide range of speculation from anti-gravity to time travel.

Jan Van Helsing claims in his book Secret Societies that, in a meeting that was attended by the members of various secret orders (Vril Gesellschaft, Thule Society, SS elite of Black Sun) and two mediums, technical data for the construction of a flying machine was gathered along with the messages that were said to have come from the solar system Aldebaran. One of Cook's scientist contacts in The Hunt for Zero Point, was a "Dr. Dan Marckus". (Cook states in his book that he has "blurred" Marckus' name and that he is "an eminent scientist attached to the physics department of one of Britain's best-known universities"). Dr. Marckus claimed that The Bell was a torsion field generator and that the SS scientists were attempting to build some sort of time machine with it. The original claims about the existence of the experiment were spread by Igor Witkowski, who claimed to have discovered the existence of the project after seeing secret transcripts of an interrogation by the KGB of SS General Jakob Sporrenberg. According to Witkowski, he was shown some classified files in August 1997 by a Polish intelligence officer (whose identity Witkowski keeps confidential), who had access to Polish government documents regarding Nazi secret weapons. This officer unveiled to him for the first time the details of the testimony of SS Officer Jakob Sporrenberg, who provided details of this secret sub-program during a questioning by Polish military officials in 1950/51, when he was imprisoned in Poland. Witkowski provides lavish details of this in his book The Truth about the Wunderwaffe. Although no evidence of the veracity of Witkowski's claims have ever been produced, these claims reached a wider audience when they were used by British author Nick Cook in his popular non-fiction book The Hunt for Zero Point. The origin, and only evidence of the story, lies solely on Witkowski's testimony of seeing secret transcripts of Sporrenberg's interrogation and his comments on it. These documents have never been made public and Witkowski claims that he was only allowed to transcribe them and was not allowed to make any copies. No other evidence has come to light. The Henge (Fly Trap)

Among Witkowski's other speculations was that a nearby structure dubbed "The Henge" may have been a test rig for the anti-gravity propulsion generated by the Bell. Witkowski said that an industrial complex at the nearby Wenceslas mine was the testing site for the Bell. In August 2005 German investigator, and GAF Staff Officer, Gerold Schelm (aka "Golf Sierra") visited "The Henge" and released his findings in November of that year. He claims to have debunked the "Henge" part of the story, demonstrating that a similar structure he discovered in the Polish city of Siechnice is merely the frame for a cooling tower, and shows both Witkowski's image and his of the completed cooling tower together for purposes of comparison. Schelm goes on to state that: The similarities between the concrete structure known as "The Henge" and the base structure of this cooling tower in Siechnice are obvious. Despite the number of columns does not match (2 at Siecnice and 11 at Ludwikowice), I am sure, that even their dimensions are almost the same. The construction features are exactly the same, leading to the assumption that the cooling tower and "The Henge" once were built using the same plans, maybe even the same construction company. I had no luck in finding out when the cooling tower in Siechnice was erected, but is in very good condition and I think it was built after WW II, maybe in the 60's or 70's. Witkowski had pointed out to Cook some metal bolts, which were visible on the top of the structure, right above every column. Witkowski concluded that those bolts had once absorbed the physical force of a heavy apparatus that must have been placed in the middle of the structure, possibly the Bell. Schelm states that: Comparing the details of both "The Henge" with the Siechnice cooling tower, the purpose of the bolts mentioned by Witkowski becomes clear: The upper metal construction of the cooling tower is resting on exactly those 12 bolts, being visible just on top of every column like they can be seen at "The Henge". Sorry, Mr. Witkowski, but at this point your theory goes down the drain. The concrete structure that you referred to as a possible "test-rig" for carrying the "Nazi-Bell" inside is no more than the remnant of a cooling tower. And, taking this fact into consideration it appears very plausible that the power plant at the northern end of the valley, next to the "Fabrica", would have had a cooling tower, and a good place to erect that cooling tower would have been the bank right next to the "Fabrica". The "Fabrica", whatever it may have produced, of course would have needed huge amounts of electricity, and this in a very remote location. It would have been feasible to build a power plant next to the factory, producing the required electricity from the coal coming from the in-place Wenceslas Mine. As Cook wrote himself, there was a power plant at the end of the valley, and Witkowski showed it to him. When Cook asked Witkowski what it was, Witkowski said: I am not sure. But whatever it is - whatever it was - I believe the Germans managed to complete it. In this light it is difficult to see, but some of the original green paint remains. You do not camouflage something that is half finished. It makes no sense. Later, he stated that he believes it to be a test-rig. Cook later stated that: I didn't buy Witkowski's test-rig thesis, but then again I wasn't dismissing it either. Witkowski went on to show Cook that "the ground within the structure has been excavated to a depth of a metre and lined with the same ceramic tiles that Sporrenberg describes in the chamber that contained the Bell. Schelm stated that: I had brought a small foldable spade with me and started digging at three or four places within the circumference of "The Henge". I didn't find anything, only bare earth, full of worms and bugs and weed roots.

Witkowski is not believed to have commented on the similar structure in Siechnice. Schelm does comment on the paint on the structure in Ludwikowice, stating "when I looked between the columns, I noticed on the south-eastern edge the remnants of what might have been a concrete rim, reaching around "The Henge" at a slightly larger diameter and about 3 meters outside the circle of columns. A portion of the rim of about 4 meters was left, the rest of the rim was either not accessible due to bushes or had been demolished long time ago. The concrete rim had been painted with the same turquoise paint that had been used for the whole structure."

In 2006 Joseph P. Farrell commented in his book, SS Brotherhood of the Bell: Witkowski also provided this author with more information that was not available when his book was published. Rainer Karlsch, a German historian who recently published a book in Germany on Hitler's nuclear program, also mentioned in his book that a team of physicists from a German university (in Giessen) has carried out a lot of research in Ludwikowice, namely in (the Henge). The result is such that there are isotopes in the construction (in the reinforcement), which can only be the result of irradiation by a strong beam of neutrons, thus that there must have been some kind of device accelerating ions, rather heavy ones. It could be calculated what was the intensity of the radiation in 1945 and generally it was very high. In other words, whatever had been tested at the Henge - and there is every indication that it was the Bell - it not only required a sturdy structure to keep it down but also it gave off strong, heavy, radiation. In his book, Hitler's Suppressed and Still-Secret Weapons, Science and Technology, Stevens wrote about a conversation in the early sixties between a friend's father and his boss at NASA, Otto Cerny, a German scientist from Operation Paperclip. At first Cerny was only vague about his previous work, dismissing it as "weird experiments on the nature of time". However, he later drew a structure made of a circle of stones with a ring around the top along with a second ring from which something hung. At some point during the conversation Cerny described something similar to a concave mirror on top of the device allowing "images from the past" to be seen during its operation. He claimed that it was possible to "go back and witness things", but not to go forward.

How close did Hitler really come to getting the Bomb? The history books say the United States and Britain comfortably won the race against Nazi Germany to build the world's first nuclear bomb. Today, that reassuring view is being nibbled away by the evidence from secret documents trickling out of private or former Soviet archives. Hidden for six decades, these papers confirm that Hitler's scientists indeed were way behind their Manhattan Project counterparts in building a Bomb. But the documents also suggest that by the end of the war in Europe, in May 1945, the Nazis had advanced farther down the nuclear road than is conventionally thought and had struck out in unexpected directions. As early as 1942, the Germans had already cracked some of the biggest conceptual problems behind making an atomic bomb. As the Reich's enemies closed in during the final months of the war, the scientists made some extraordinary technical strides. Using a prototype reactor hastily assembled in a disused beer cellar in southwestern Germany, a team nearly achieved a self-sustaining chain reaction, the key step to manufacturing nuclear explosive. According to two new documentary finds unveiled this year, Hitler's scientists even tested a nuclear weapon. The device that these days would be called a "dirty" bomb. The Reich scientists also sketched plans for the world's first mini-nuke missile. The Nazis were not at all close to having an atomic bomb like those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. The German progress towards such weapons was comparable to what the Americans had achieved by the summer of 1942. During the last desperate year-and-a-half of war... a group of physicists who had been working on nuclear reactors, nuclear reactions and hollow-point arrangements of high explosives put them together to test a nuclear device. ~ Mark Walker, a professor of history at Union College in Schenectady, New York. Work in atomic physics before World War II led scientists in Germany, as well as in Britain and the United States, to speculate that an awesome release of energy could be obtained if the nucleus of a heavy atomic isotope was split apart, its neutrons whacking into other atoms in a chain reaction. Prompted by warnings from Albert Einstein to President Roosevelt of the Nazis' interest in a bomb, the United States launched the Manhattan Project on Dec. 7 1941, coincidentally the eve of the attack on Pearl Harbor that prompted its entry into World War II. The scheme would cost the equivalent of some 30 billion dollars and muster thousands of scientists and engineers, many of them Jewish scientists who had fled Nazi prosecution of their crimes. That same winter, the German military looked into the prospects for a Bomb and concluded the goal was so tough it was not worth the huge investment of billions.