Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Proprietary Estoppel

Uploaded by

Andrew RobertsCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Proprietary Estoppel

Uploaded by

Andrew RobertsCopyright:

Available Formats

The modern law of proprietary estoppel?

Nigel Thomas Maitland Chambers Lincolns Inn London WC2A 3SZ

1.

The House of Lords has finally had the opportunity of reviewing and clarifying(?) the equity known as proprietary estoppel in two of its recent decisions: Cobbe v Yeomans Row Management Ltd [2008] 1 WLR 1752 and Thorner v Major [2009] 1 WLR 776.

2.

Of the two, Thorner is perhaps the more illuminating as it is a decision based upon facts that, classically, form the basis for most of the reported cases on proprietary estoppel (i.e. a farmer promising a younger relative that in exchange for his help on the farm, for little or no remuneration, the farm will be his one day) but Cobbe is of special significance as it seems to draw a line in the sand. Or does it?

3.

Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe, who gave the lead judgment in Thorner, with perhaps a wry smile, chose to commence his opinion [29] with a quotation from Simon Gardner, An Introduction to Land Law (2007) page 101 There is no definition of proprietary estoppel that is both comprehensive and uncontroversial (and many attempts at one have been neither).

4.

Please note, as well, a revelatory aside of Lord Walker in Thorner [56]: I would prefer to say (while conscious that it is a thoroughly questionbegging formulation) that to establish a proprietary estoppel the relevant assurance must be clear enough. What amounts to sufficient clarity, in a case of this sort, is hugely dependent on context.

2 5. But to begin at the beginning, as Lord Walker pointed out in the opening paragraph [29] of his opinion in Thorner there was general agreement amongst academic writers that the doctrine is based on three main elements: (a) (b) (c) 6. a representation or assurance made to the claimant reliance on it by the claimant detriment to the claimant in consequence of his (reasonable) reliance.

Earlier judicial formulations are to like effect: (1) As formulated by Mr Edward Nugee QC in Re Basham Deed [1986] 1 WLR 1498 at 1503 and as approved by Robert Walker LJ (as he then was) in Gillett v. Holt [2001] Ch 210: The Plaintiff relies on proprietary estoppel, the principle of which in its broadest form, may be stated as follows: where one person, A, has acted to his detriment on the faith of a belief, which was known to and encouraged by another person, B, that he either has or is going to be given a right in or over Bs property, B, cannot insist on his strict legal rights if to do so would be inconsistent with As belief. (2) Oliver J (as he then was) put the matter in Taylor Fashions Ltd v. Victoria Trustee Co Ltd (1979) [1982] QB 133n thus: If A, under an expectation created or encouraged by B that A shall have a certain interest in land thereafter, on the faith of such expectation and with the knowledge of B and without objection from him, acts to his detriment in connection with such land, a Court of Equity will compel B to give effect to such expectation.

7.

In its practical application the principle by which it operates is not very different to common intention constructive trusts: Grant v. Edwards [1986] Ch. 638 and Hiscock

3 v. Oxley [2004] EWCA Civ 546. Both rely upon certain shared characteristics e.g. a representation or promise, which is intended to be, or it is known that, it will be, relied upon and in reliance thereon the promisee acts to his or her detriment. 8. The difference between the principles of constructive trusts and proprietary estoppel is that the former concerns an agreement arrangement or understanding about the ownership or sharing the ownership of property, generally (but not exclusively) before it is acquired, whilst the emphasis of the latter is upon a representation whereby there is the acquisition of rights in or over property which is already (or about to be) owned by the promisor. And as we shall see, once proved, the Court must enforce the terms of the constructive trust whilst in the case of proprietary estoppel it has more flexibility. 9. One further characteristic of proprietary estoppel to note was described by Hoffman LJ (as he then was) in Walton v. Walton [1994] CA Transcript No. 479 21. But none of this reasoning applies to equitable estoppel, because it does not look forward into the future and guess what might happen. It looks backwards from the moment when the promise falls due to be performed and asks whether, in the circumstances which have actually happened, it would be unconscionable for the promise not to be kept.

Representation/Assurance 10. The person seeking to assert the estoppel (A) must establish that the person who owns the property (O), or his agent, or his predecessor in title, has represented that he (A) will obtain an interest in property either by: (i) making an express promise or

4 (ii) encouraging A to believe that he will obtain such an interest by words or conduct or (iii) encouraging As belief passively and by remaining silent i.e. acquiescence see Snells Equity (31st ed) para. 10-17. 11. The promise can be vague or even equivocal, and certainly less than is needed to enforce a contractual obligation, what however is essential is to show that it was intended that it should be relied upon or that the promisee was reasonable in so doing: see Thorner per Lord Walker at [56] and Lord Neuberger at [84] and [85]. It is not necessary therefore to show that Os promise was said by him to be irrevocable what matters is that it was reasonable for A to so act to his detriment: Gillett v. Holt [2001] Ch 210. 12. A commonly encountered scenario involves the family farm: a son or other relative stays at home to work on the farm for payment that amounts to little more than pocket money, in course of time he wishes to marry and proposes to move away to earn a reasonable wage, he is induced to stay at home with a promise that the farm will be left to him by Will: Gillett v. Holt, and Uglow v. Uglow [2004] WTLR 1183 CA. 13. Promises to leave businesses comprising of property and other assets made on the same basis are also common Gillett v. Holt (farm/ agricultural business) Wayling v. Jones [1995] 2 FLR 1029 (hotel). 14. The cases also show other types of relationships such as a needy older person who promises to leave his or her estate, or property, or a house for life to A, if he or she continues to look after O: Griffiths v. Williams [1978] 2 EGLR 121 Jennings v. Rice [2003] 1 P&CR 8.

5 15. And note that standing by and thus encouraging As belief by acquiescence can also amount to encouragement e.g. where a landlord and two tenants acted under a common assumption that an option to renew was void: Taylors Fashions Ltd v. Liverpool Victoria Trustees Co. Ltd. 16. Of course, it must be the case that normally O knows all of the material facts viz that the property was his, that A was acting on Os representation and that he, O, could interfere. Otherwise Os behaviour would not be unconscionable. On rare occasions (which will indeed be very rare) Os knowledge is not essential if Os conduct in encouraging A to act to his detriment would nevertheless make it inequitable that he should be allowed to stand on his strict rights. Reliance: Expectation or belief 17. A must have acted in the belief that he either has or would acquire a sufficient interest in the property to justify acting to his detriment. For instance, the son who stayed on the farm because he was promised he would inherit it or a housekeeper who was persuaded to stay to look after O who promised A the house: Wakeham v. MacKenzie [1968] 1 WLR 1175. 18. The conventional view has always been that there is no room for estoppel where negotiations are expressly made subject to a subject to contract term and such indeed is the usual outcome of estoppel claims in such circumstances: see note 92 para. 10-19 of Snell for a list of such decisions a view now endorsed by the House of Lords see Lord Scott in Cobbe at [25]. Detriment 19. Detriment suffered by A is essential to establishing the equity:

6 The overwhelming weight of authority shows that detriment is required. But the authorities also show that it is not a narrow or technical concept. The detriment need not consist of the expenditure or money or other quantifiable financial detriment, so long as it is something substantial. The requirement must be approached as part of a broad inquiry as to whether repudiation of an assurance is or is not unconscionable in all the circumstances. per Robert Walker LJ (as he then was) in Gillett v. Holt. Slade LJ in Jones v. Watkins said: the detriment which the representee must be shown to have suffered falls to be judged at the moment when the representor proposes to go back on his representation. Dunn LJ in Greasley v. Cooke [1980] 1 WLR 1306 at 1313/1314: There is no doubt that for proprietary estoppel to arise the person claiming must have incurred expenditure or otherwise have prejudiced himself or acted to his detriment. 20. Balcombe LJ in Wayling v. Jones analysed what, in practical terms, amounts to detriment. His analysis is quoted with approval by Robert Walker LJ in Gillett v. Holt: (1) There must be a sufficient link between the promises relied upon and the conduct which constitutes the detriment see Eves v. Eves [1975] 1 WLR 1338, 1345C-F, in particular per Brightman J, Grant v. Edwards [1986] Ch 638, 648-649, 655-657, 656G-H, per Nourse LJ and per Browne-Wilkinson V-C and in particular the passage where he equates the principles applicable in cases of constructive trust to those of proprietary estoppel. The promises relied upon do not have to be the sole inducement for the conduct: it is sufficient if they are an inducement Amalgamated Property Co v. Texas Bank [1982] QB 84, 104-105. Once it has been established that promises were made, and that there had been conduct by the plaintiff of such a nature that inducement may be inferred then the burden of proof shifts to the defendants to establish that he did not rely on the promises Greasley v. Cooke [1980] 1 WLR 1306; Grant v. Edwards [1980] Ch 638, 657.

(2)

(3)

7 21. Detriment can be divided into expenditure and non expenditure or other detriment. (i) Expenditure: (a) the classic decision of Dillwyn v. Llewellyn (1862) 4 De G F & J 517 where A encouraged by O built a house on Os land and O failed to transfer the land to A: and see Inwards v. Baker [1965] 2 QB 29 involving similar facts; (b) by contributing to the purchase price and providing cash for repairs Jiggins v. Brisley [2003] EWHC 841; (c) it can include expenditure by A on his own land in expectation of obtaining a right over Os land as where A built on his own land in expectation of a right to obtain water from Os canal: Rochdale Canal Company v. King (2) (1853) 16 Beav 630. (2) Other detriment: this takes the form most commonly of the provision of services or foregoing opportunities elsewhere: (a) On assurances that A would be granted a right of way over Os land, A disposed of part of his land: Crabb v Arun D.C. [1976] Ch 179; (b) helping in a business or farm and giving up the chance of other opportunities or more remunerative work elsewhere: Re Basham and Gillett v. Holt;

8 (c) a giving up his job and going to live near O in a house owned by O: Jones v. Jones [1997] 1 WLR 438; (d) foregoing other business opportunities to run the family business for 30 years at a reduced wage Newman v. Blanton [2002] All ER (D) 107 (Jun); (e) a soi-dissant actress gave up what the Court thought was not a promising career to look after an alcoholic partner: Grundy v. Ottey [2003] EWHC Civ 1176. Land Registration Act 2002 s. 116 22. By section 116 of the LRA 2002 it is provided as follows: It is hereby declared for the avoidance of doubt that, in relation to registered land, [each of] the following (a) . has effect from the time the equity arises as an interest capable of binding successors in title (subject to the rules about the effect of disposition on priority). 23. The section builds on the old practice of HM Land Registry which was to permit a caution or notice to be entered upon notification of the right. The new section clarified the position by confirming the proprietary nature of such an estoppel by declaring that it has effect as soon as it arises. The section cannot solve the difficulty that until the Court makes a declaration the extent of the equity is uncertain will the Court grant A an interest in land or merely monetary or some other compensation? an equity by estoppel

9 Extent and Satisfaction of the equity 24. Once established how will the court satisfy the equity? One of the few differences between proprietary estoppel and constructive trusts is that a constructive trust is founded upon a common intention (i.e. agreement arrangement or understanding) so once found, the Court must give effect to this common intention, whereas for proprietary estoppel the courts will simply provide the minimum equity to do justice. 25. The starting point is to establish what was As expectation. That he would inherit the entire farm, and the live and dead stock, be given the business, Os residuary estate or a home for life? 26. In cases such as Wayling v. Jones the promise made by O, the homosexual partner of A, was that he would leave to A his hotel and in reliance upon those promises A acted as Os companion, chauffeur and business associate until Os death and in exchange he was given pocket money and some expenses. The Court ordered that the entire proceeds of sale of the hotel should be transferred to A. In many of the farming cases especially where the farm in question is a small family farm the order is to transfer the entire farm together with the live and dead stock. 27. However, since Gillett v. Holt there seems to have developed a new, and stricter, approach to satisfying the equity. Having placed the doctrine on a clear footing Robert Walker LJ (as he then was) in the important decision of Jennings v. Rice [2002] EWCA Civ 159 set about reminding everyone that the job of the Court was to do the minimum equity to do justice (Crabb v. Arun DC). In Jennings O had promised A in exchange for looking after her, her house and contents which were valued at 435,000 the Court awarded him 200,000.

10 28. In short, the issue is one of deciding whether to give effect to the expectation of A or will justice be done by awarding him something less. So the court will consider: (a) (b) (c) (d) the conduct of O and A; the quality of Os assurances; the extent and nature of Os assets the extent of As detriment as for instance in Jennings v. Rice. Where the Court considered what O would have paid had she employed carers or gone into a nursing home viz Robert Walker LJs cross check. 29. Therefore although the starting point will be As expectation which will be the predominant consideration when satisfying the equity, that said there appears to be a clear move away from a position where the Court was simply concerned to fulfil As expectation to a more flexible and proportionate approach. How is the equity to be satisfied? 30. (a) transfer of property or an interest in property as the cottage in Re Basham; a house and farm as well as business assets in Gillett v. Holt. The grant of a lease Griffiths v. Williams [1978] 2 EGLR 121 or an easement Crabb v. Arun DC [1976] Ch 179. (b) monetary compensation as in Dodsworth v. Dodsworth (700 compensation for improvements but a licence to occupy until it was paid) and Jennings v. Rice. In Wayling v. Jones as noted above the court ordered the proceeds of sale of the hotel be transferred to A. In Gillett v. Holt the Court ordered the

11 transfer of real property but also damages of 100,000 to compensate Mr Gillett for his exclusion from all the rest of the farming business. (c) charge for expenditure: a charge or equitable lien may be ordered to cover As expenditure on or value of his improvements. Does proprietary estoppel still have a role in commercial transactions? 31. 32. In the light of Cobbe it seems unlikely. Lord Neuberger in Thorner stressed the role of equitable estoppel in the familial and personal [97] and in distinguishing Cobbe from the decision in Thorner he identified two factors [94] to [96]. 33. First, the nature of the uncertainty in two cases is entirely different (the appeal in Thorner had been defended on the basis that the promise to leave the farm was insufficiently certain in that its extent might change) and secondly the relationship between the parties in Cobbe was entirely arms length and commercial, and the person raising the estoppel was a highly experienced businessman. In Thorner, however, the relationship was familial and personal. [97]. 34. However there are two important cases worthy of note: one pre, and the other post Cobbe. These cases seem to point to the conclusion that where a proprietary estoppel can be said to amount to a constructive trust, then, it can have a role in a commercial transaction. The first is a decision of the Court of Appeal in Kinane v Mackie Conteh [2005] EWCA Civ 45 and the other Herbert v Doyle and Talati [2008] EWHC 3423 (CH) (Mr Mark Herbert QC sitting as a Deputy Judge of the Chancery Division).

12 35. Kinane was cited in argument in Cobbe but not referred to in the opinions. The issue in the appeal was whether a security agreement was enforceable notwithstanding section 2(1) of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989. The Court of Appeal held that it was, on the basis of a constructive trust, so it was within section 2(5) of the 1989 Act i.e. a constructive trust which is an exception to the provision requiring that contracts concerning land have to be in writing. 36. Neuberger LJ (as he then was) in coming to his conclusion relied heavily upon the decision in Yaxley v Gotts [2000] Ch 174 in which it had been pointed out by Robert Walker LJ that there are large areas where the two concepts [proprietary estoppel and constructive trusts] do not overlap but that it was well established that the two concepts coincide in the area of a joint enterprise for the acquisition of land. 37. In Kinane, Mr Kinane advanced a sum of $80,000 on the strength of a letter of 8 November 2001 which he believed, on the Defendants assurances, gave him adequate security i.e. a mortgage or equivalent. The letter was not sufficient for the purposes of s. 2(1). He pleaded a proprietary estoppel which could also properly amount to a constructive trust [45], so as to come within s. 2(5) of the 1989 Act. 38. In coming to his conclusion Neuberger LJ specifically reminded himself that [40]: When considering that question, one must, I think, avoid regarding the subsection as an automatically available statutory escape route from the rigours of section 2(1) of the 1989 Act, simply because fairness appears to demand it. Arden LJ in her judgment considers the same points at some length: see paragraphs [26] to [28].

13 39. In Herbert v Doyle and Talati the Learned Judge delayed giving judgment in order to consider the decision of the House of Lords in Cobbe. 40. The facts were as follows: the claimant alleged that under an oral argument, a dentists practice, which owned nine parking spaces in a car park on a property owned by him, agreed to transfer certain car parking spaces to him, in return for replacement car parking spaces. On the strength of this agreement the claimant went ahead and developed his property. 41. Distinguishing Cobbe and following Kinane the Deputy Judge found that if all the requirements of a proprietary estoppel were found, and that the estoppel can properly be said to amount to a constructive trust, then the claim will not fail simply because all the requirements of section 2 were not met. And this despite Lord Scotts admittedly obiter view in Cobbe [29] My present view, however, is that proprietary estoppel cannot be prayed in aid in order to render enforceable an agreement that statute has declared to be void. That said, he seems to have answered his own point a little further on into the paragraph As I have said, however, statute provides an express exception from constructive trusts.

14 42. So the conclusion seems to be even if it is a commercial transaction do not give up on proprietary estoppel but only, that is, if you can succeed on establishing a constructive trust as well.

Nigel Thomas Maitland Chambers Lincolns Inn October 2009

You might also like

- Defending Freedom of Contract: Constitutional Solutions to Resolve the Political DivideFrom EverandDefending Freedom of Contract: Constitutional Solutions to Resolve the Political DivideNo ratings yet

- Freehold Covenants (2020)Document13 pagesFreehold Covenants (2020)mickayla jonesNo ratings yet

- Equitable EstoppelDocument24 pagesEquitable EstoppelLina Khalida100% (2)

- TrespassDocument23 pagesTrespassAllen Hsu100% (8)

- Mr. Spanner Is Essentially A Contract With The Provisions and Binds The Parties by Referring To The Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 (LTA 1954)Document10 pagesMr. Spanner Is Essentially A Contract With The Provisions and Binds The Parties by Referring To The Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 (LTA 1954)atubNo ratings yet

- Common Law 3Document14 pagesCommon Law 3Taha MiyasahebNo ratings yet

- Land Law Cracks On The MirrorDocument12 pagesLand Law Cracks On The MirrorTimothy Yu Gen HanNo ratings yet

- Promissory Estoppel - SupplementaryDocument4 pagesPromissory Estoppel - SupplementaryAlvin OuNo ratings yet

- The Rule in Rylands V FletcherDocument3 pagesThe Rule in Rylands V Fletcherhafidz152100% (1)

- Maxims of Equity: Key Principles of Fairness in LawDocument9 pagesMaxims of Equity: Key Principles of Fairness in LawDrjKmr100% (1)

- Land Law Martin DixonDocument43 pagesLand Law Martin DixonEdwin Oloo100% (1)

- EstoppelDocument4 pagesEstoppelAbhishekKuleshNo ratings yet

- We Do This at Common Law and That at Equity - A BurrowsDocument16 pagesWe Do This at Common Law and That at Equity - A BurrowsJared Tong100% (1)

- Equity and Trusts Lecture Notes Semester 12Document37 pagesEquity and Trusts Lecture Notes Semester 12TheDude9999100% (2)

- Origins and Development of Common Law and EquityDocument3 pagesOrigins and Development of Common Law and EquityAnn Ruslan50% (2)

- Three Certainties of A TrustDocument7 pagesThree Certainties of A TrustJake Lannon100% (1)

- Nemo dat quad non habet principle and exceptionsDocument7 pagesNemo dat quad non habet principle and exceptionsRITIKANo ratings yet

- Do The Changes Brought About by The Land Registration Act 2002, With Particular Focus On Adverse Possession, Do Enough To Protect Purchasers From Overriding InterestsDocument15 pagesDo The Changes Brought About by The Land Registration Act 2002, With Particular Focus On Adverse Possession, Do Enough To Protect Purchasers From Overriding InterestsHamza SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Breach of Contract RemediesDocument6 pagesBreach of Contract RemediesAbdul Salam khuhro100% (2)

- Law of Tort CasesDocument203 pagesLaw of Tort Caseskuboja_joram100% (2)

- Rule of PresumptionDocument2 pagesRule of PresumptionArun Shokeen75% (4)

- Equity Personal NotesDocument65 pagesEquity Personal NoteshouselantaNo ratings yet

- Equity & Trusts Tutorial Exercises GuideDocument14 pagesEquity & Trusts Tutorial Exercises GuideiramNo ratings yet

- Maxims of EquityDocument27 pagesMaxims of Equitychinnyaustin50% (2)

- Tracing in EquityDocument34 pagesTracing in EquityOlman FantasticoNo ratings yet

- Mandatory InjunctionsDocument25 pagesMandatory Injunctionsabchoudry100% (1)

- Maxims of EquityDocument7 pagesMaxims of EquitynaveedLLBNo ratings yet

- Resulting Trust Essay PlanDocument3 pagesResulting Trust Essay PlanSebastian Toh Ming WeiNo ratings yet

- Resvision Breach of Trust and TrusteeDocument6 pagesResvision Breach of Trust and TrusteebluekatoNo ratings yet

- Promissory Estoppel: Nor Asiah MohamadDocument68 pagesPromissory Estoppel: Nor Asiah Mohamadfaridariffin91% (11)

- Trespass To Land NotesDocument1 pageTrespass To Land NotesMayank GautamNo ratings yet

- Sources of Law in GhanaDocument20 pagesSources of Law in GhanaKruh Kwabena Isaac100% (3)

- The Free Movement of Persons - EU LawDocument7 pagesThe Free Movement of Persons - EU LawJames Robert KrosNo ratings yet

- Tort Law Trespass PersonDocument2 pagesTort Law Trespass PersonZafar Azeemi100% (1)

- 6 - Private NuisanceDocument19 pages6 - Private NuisanceL Macleod100% (1)

- Equity and Trusts EssayDocument7 pagesEquity and Trusts EssayKatrina BestNo ratings yet

- Balkan Energy CaseDocument42 pagesBalkan Energy CaseNii Armah100% (1)

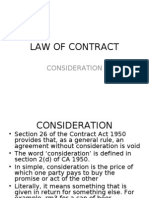

- Law of Contract: ConsiderationDocument19 pagesLaw of Contract: ConsiderationJacob Black100% (1)

- A Presentation On DamagesDocument21 pagesA Presentation On DamagesnsthegamerNo ratings yet

- 6 Contract - RemediesDocument4 pages6 Contract - RemediesglenlcyNo ratings yet

- Freehold CovenantsDocument7 pagesFreehold CovenantsFifi JarrettNo ratings yet

- HISTORY OF EQUITY DEVELOPMENTDocument100 pagesHISTORY OF EQUITY DEVELOPMENTRenee Francis80% (5)

- LEASES 1. INTRODUCTION and DEFINITION OFDocument22 pagesLEASES 1. INTRODUCTION and DEFINITION OFHenderikTanYiZhouNo ratings yet

- Law of Juristic Act and ContractDocument45 pagesLaw of Juristic Act and ContractWISDOM-INGOODFAITH100% (1)

- Promissory Estoppel - Requirements and Limitations of The DoctrineDocument40 pagesPromissory Estoppel - Requirements and Limitations of The Doctrinecorter177No ratings yet

- 19 Traditional Maxims of Equity ExplainedDocument8 pages19 Traditional Maxims of Equity ExplainedMichael FociaNo ratings yet

- Equity LecturesDocument106 pagesEquity LecturesDekweriz100% (2)

- Capacity To ContractDocument33 pagesCapacity To ContractAbhay MalikNo ratings yet

- Distinguishing private and public nuisance in a construction disputeDocument21 pagesDistinguishing private and public nuisance in a construction disputeChinYeeTuck100% (1)

- DuressDocument11 pagesDuressPrasanga Priyankaran100% (1)

- Whereas Defined Pursuant to Supreme Court Annotated Statute Trinsey v. Pagliaro, D.C. Pa. 1964, 229 F. Supp. 647: Statements of counsel, in their briefs or their arguments are not facts before the court and are therefore insufficient for a motion to dismiss or for summary judgment.Document3 pagesWhereas Defined Pursuant to Supreme Court Annotated Statute Trinsey v. Pagliaro, D.C. Pa. 1964, 229 F. Supp. 647: Statements of counsel, in their briefs or their arguments are not facts before the court and are therefore insufficient for a motion to dismiss or for summary judgment.in1or50% (2)

- Casebook On Contract Law - (4 Enforceability of Promises Consideration and Promissory Estoppel)Document50 pagesCasebook On Contract Law - (4 Enforceability of Promises Consideration and Promissory Estoppel)susanna wahidNo ratings yet

- Maxims of EquityDocument13 pagesMaxims of Equitydenesh11No ratings yet

- 14 08 04 Letter FiledDocument7 pages14 08 04 Letter FiledwarriorsevenNo ratings yet

- The Dignity of Commerce: Markets and the Moral Foundations of Contract LawFrom EverandThe Dignity of Commerce: Markets and the Moral Foundations of Contract LawRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- 6 - Proprietary EstoppelDocument7 pages6 - Proprietary Estoppelvivian cheungNo ratings yet

- BC Sea View Ffynnongroew-ISO A1 (594 X 841) PDFDocument1 pageBC Sea View Ffynnongroew-ISO A1 (594 X 841) PDFAndrew RobertsNo ratings yet

- Cill DetailsDocument1 pageCill DetailsAndrew RobertsNo ratings yet

- Latant DamageDocument3 pagesLatant DamageAndrew RobertsNo ratings yet

- Introduce New Regulations HMODocument2 pagesIntroduce New Regulations HMOAndrew RobertsNo ratings yet

- Boundary DisputesDocument17 pagesBoundary DisputesAndrew Roberts100% (1)

- A Breach of Planning ControlDocument3 pagesA Breach of Planning ControlAndrew RobertsNo ratings yet

- Case 1Document9 pagesCase 1bhidhiNo ratings yet

- Estoppel in Equity: Discussion of Unification in Ireland Study NotesDocument6 pagesEstoppel in Equity: Discussion of Unification in Ireland Study NotesWalter McJasonNo ratings yet

- Courts' wide discretion in proprietary estoppel claimsDocument3 pagesCourts' wide discretion in proprietary estoppel claimsAnonymous lRZccFw100% (1)

- Equity and Trusts Lecture on Common Intention Constructive TrustsDocument34 pagesEquity and Trusts Lecture on Common Intention Constructive TrustsravinNo ratings yet

- LLB 20503: Estoppel II - Promissory Estoppel IntroductionDocument15 pagesLLB 20503: Estoppel II - Promissory Estoppel IntroductionSiva NanthaNo ratings yet

- Perfecting Imperfect Gifts and Trusts Have We Reached The End of The Chancellors FootDocument7 pagesPerfecting Imperfect Gifts and Trusts Have We Reached The End of The Chancellors FootCharanqamal SinghNo ratings yet

- Proprietary EstoppelDocument14 pagesProprietary EstoppelAndrew Roberts100% (1)

- 5 Propriatory EstoppelDocument8 pages5 Propriatory Estoppeldawood imranNo ratings yet

- Sean Wilken, Karim Ghaly - The Law of Waiver Variation and Estoppel-Oxford University Press (2012)Document640 pagesSean Wilken, Karim Ghaly - The Law of Waiver Variation and Estoppel-Oxford University Press (2012)Luiza IonescuNo ratings yet

- Revision - Coownership (Trust) Proprietary Estoppel-2Document13 pagesRevision - Coownership (Trust) Proprietary Estoppel-2Sumukhan LoganathanNo ratings yet

- Satisfying The Minimum Equity Equitable Estoppel Remedies After Verwayen PDFDocument44 pagesSatisfying The Minimum Equity Equitable Estoppel Remedies After Verwayen PDFwNo ratings yet

- 2021-22 Land Topic 3 (Lecture 6) Proprietary EstoppelDocument26 pages2021-22 Land Topic 3 (Lecture 6) Proprietary EstoppelChun Fai ChengNo ratings yet

- ANSWERDocument10 pagesANSWERRichard Conrad Foronda SalangoNo ratings yet

- The Doctrine of Promissory PDFDocument25 pagesThe Doctrine of Promissory PDFAmita SinwarNo ratings yet

- Constitution of Trusts - Equity Trust IIDocument45 pagesConstitution of Trusts - Equity Trust IIunguk_189% (9)

- Proprietary Estoppel SlidesDocument35 pagesProprietary Estoppel SlidesAnushi KalhariNo ratings yet

- Case Law - PropertyDocument10 pagesCase Law - Propertyminha aliNo ratings yet

- HK Land Law Looks at Equity & EstoppelDocument11 pagesHK Land Law Looks at Equity & EstoppelpppNo ratings yet

- Function of The Assignment: Legal EstateDocument14 pagesFunction of The Assignment: Legal EstateParis CarterNo ratings yet

- WLDoc 17 1 20 11 - 17 AMDocument13 pagesWLDoc 17 1 20 11 - 17 AMAnonymous yr4a85No ratings yet

- Low Heng Leon Andy V Low Kian Beng Lawrence (2013) 3 SLR 710 PDFDocument21 pagesLow Heng Leon Andy V Low Kian Beng Lawrence (2013) 3 SLR 710 PDFHenderikTanYiZhouNo ratings yet

- Proprietary EstoppelDocument5 pagesProprietary Estoppelminha aliNo ratings yet

- BP0153338 Land Law Semester I3Document5 pagesBP0153338 Land Law Semester I3Chand LughmaniNo ratings yet

- Guindarajoo V SatgunaDocument45 pagesGuindarajoo V Satgunaeghl89No ratings yet

- Promisory Estoppel - PUDocument25 pagesPromisory Estoppel - PUArkadeep PalNo ratings yet

- Neil Duxbury: Michaelmas Term Lectures: Land LawDocument7 pagesNeil Duxbury: Michaelmas Term Lectures: Land LawJoshNo ratings yet

- Land Law Problem QuestionDocument6 pagesLand Law Problem QuestionPaula Ghergu100% (1)

- Ashley Wynne - Family NotesDocument17 pagesAshley Wynne - Family Notessky22blueNo ratings yet

- AMK - SLR (2002) 37 (17-19) The Many Doctrines of Promissory EstoppelDocument3 pagesAMK - SLR (2002) 37 (17-19) The Many Doctrines of Promissory Estoppelpsfx100% (1)