Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Contextualizing Blame in Mothers' Narratives of Child Death in Rural Guatemala

Uploaded by

Wuqu' KawoqOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Contextualizing Blame in Mothers' Narratives of Child Death in Rural Guatemala

Uploaded by

Wuqu' KawoqCopyright:

Available Formats

Contextualizing Blame in Mothers Narratives of Child Death in Rural Guatemala

Anita Chary Wuqu Kawoq; Washington University in St. Louis, School of Medicine & Department of Anthropology

Introduction If you only have two kids and one dies, you just have one left. And if that one dies, then you have nothing. Dona Elenas words are a testament to the reality of child loss in the rural Maya village of Kexel, Guatemala. Kexel is a place where one-fourth of mothers have experienced the death of at least one child; it is a place where babies are cautiously named only at three or four months of age, when their parents have more hope that they will survive. Due to a history of anti-indigenous violence and discrimination, the Maya of Guatemala bear a disproportionate burden of the countrys poverty (Pan American Health Organization, 1998). Accordingly, Maya communities tend to experience higher rates of child mortality than the rest of the nations population of mixed ladinos and European criollos. Kexel is no exception: its child mortality rate of 54 per 1000 live births exceeds the Guatemalan average of 45 per 1000 live births (World Health Organization, 2006). Most families of Kexel live in extreme poverty. Few of Kexels 500 Spanish and Kichee-speaking residents have land holdings because nearly all local land is in the hands of plantation owners. As such, the people of Kexel can expect income for only six months of the year from day-labor during the sugar cane and coffee harvests. Largely abandoned by local politicians, the village lacks potable water, sanitation infrastructure, and access to healthcare. As a result, many community children suffer from debilitating and sometimes life-threatening malnutrition and parasitic infections. At the request of community leaders, the non-governmental organization Wuqu Kawoq began to provide free health care in Kexel four years ago. Through our clinical work and the

implementation of child health and water purification projects, we became aware of many families struggles with child illness and death. As childcare is primarily a womans duty in Kexel, mothers especially bear the burden of child loss. Mothers seek explanations for child deaths in order to cope and grieve, and blame plays a prominent role in their narratives. Medical practitioners blame mothers for negligence, mothers blame themselves for their perceived ignorance, and mothers blame other community members for sending sicknesses and death upon their children. Drawing on years of clinical work, participantobservation, community-wide surveys, and ethnographic interviews, this paper explores how these forms of blame are manifestations of the political and economic climate of Guatemala. It also seeks to analyze the social and psychological functions of blame. Troublingly, what emerges is a picture in which blame is always targeted at the local community. In Kexel, accusatory interpretations of child death not only create and exacerbate divisions within the community, but also ignore the structural inequalities that contribute to high child mortality rates. The dangerous result is that the impoverished people of Kexel--especially mothers themselves--assume responsibility for child death.

Case Study 1: The Hospital As the rickety van swerved through midday traffic on the way to the National Hospital of Mazatenango, my stomach churned over every pothole. I glanced back at Celestina, who was holding her tiny jaundiced baby in her arms. Three days old and four pounds, the little girl was dying. Celestinas somber expression betrayed her familiarity with the situation; at age 39, she had already lost eight children. Just an hour before, a Wuqu Kawoq physician had been examining the baby and had

convinced Celestina and her husband Jose that the only hope of saving the child was going to the hospital. At the gates of the National Hospital, we pleaded with a skeptical security guard to let us in. He relented upon learning of the babys enrollment in a United States health project, but stipulated that only myself, the mother, and the baby could enter. When we entered the emergency room, the head nurse, a plump ladina, took the baby from Celestinas arms and barked, You didnt take care of yourself during your pregnancy. Look at this malnourished baby! Why didnt you eat anything when you were pregnant? Celestina stoically accepted the criticism. She did not respond that her husband had not had reliable work for the past year, that the family was in debt, and that most days she subsisted on only tortillas and salt. Instead, she stood deferentially as the nurse disparagingly asked the name of the child. We havent named her yet, Celestina spoke softly. What do you mean you havent named her? Go talk to her father and decide on a name! We cant admit a baby who doesnt have a name, the nurse spat. Celestina hurried off to the front gate as the nurse placed an IV. When she returned with the name Ana Victoria, the nurse scolded her for dressing the umbilical stump with ash, an innocuous substance, as per Mayan custom in the area. Loudly, for Celestinas benefit, she pronounced the child septic. Though the nurses harsh demeanor shocked me, I soon came to realize how typical this type of encounter was for indigenous women in Kexel. Norma, a young mother of six, related a similar tale to us. Towards the end of her last pregnancy, she went to the hospital because she felt her child had stopped moving in her womb. The non-Mayan doctor who performed an ultrasound told her, You picked up a virus that killed the baby when you went to the river to relieve yourself. The doctor had assumed that Norma was poor and had no latrine, and then blamed her childs death on her poverty and ignorance.

Another young mother, Nanci, had also taken her dying baby to the hospital for seizures and severe weight loss. Upon her arrival, despite her insistence that she had had monthly prenatal care, the hospital staff wrote in her record that she had never seen a doctor during the pregnancy. Two nurses also told Nanci that it was her fault the baby was dying, and in the following months of the childs decline, Nanci frequently broke down crying in guilt and helplessness. Indeed, many Mayan women have shared similar stories of being blamed by non-Mayan health professionals for their childrens sicknesses and deaths. At the individual level, blaming the patient can serve as a coping mechanism for medical practitioners who see the same devastating situations day in and day out. Desensitization to suffering and interpretation of patient illness as self-created are common among health care professionals not only in Guatemala, but all over the world. At a broader level, the attitudes and behavior of Guatemalan hospital staff reinforce the existing racial hierarchy, in which the mixed ladino or European criollo has authority over the ignorant indgena. They also distinguish themselves ethnically and socioeconomically from the indigenous other through their condemning and condescending actions. Additionally, hospital staff who blame Mayan women for their childrens deaths effectively obscure the states contributions to high child mortality rates. Inaccessible health care, anti-indigenous discrimination, abysmal educational opportunities, labor exploitation, and lack of sanitation infrastructure are all ignored in the unsympathetic practitioners interpretation of illness. The result is that impoverished Mayan mothers, rather than the state, shoulder the burden of child health, and accordingly become the targets of blame for child death.

Case Study 2: Guilt and the Perception of the Self

I was foolish, Tina began mournfully. Her eyes reddened as she began the tale of her third child, who had died at two days old. At twenty-two, Tina had been sick throughout her pregnancy with periodic fevers and chills. When her little son was born, he too had a fever. Her voice faltered as she described the cold bath her mother-in-law gave the baby to bring down his fever, his subsequent refusal to nurse, and the midwifes attempt to lift his fallen fontanelle by using her finger to clear out his throat. She should have known better than to allow it, Tina said. The baby grew weaker over the next day, turned purple, and stopped breathing. He died in his fathers arms. Tinas eyes filled with tears as she spoke softly, He was with me for one night and nothing more. Tina scrutinized each of her actions from the time of her sons conception to his death. If only she had gone to the doctor for her fevers, if only she had refused to bathe the baby, if only she had stopped the midwife from lifting the tender boys fontanelle with so much force, what would have happened? Now, at forty-three, Tina knows about life-saving incubators in the hospital. If only she had known to take him to the hospital, she cried, he might still be alive today. But he is gone, and I am to blame, she said. As Tina dabbed at her eyes, her tortured expression reflected the guilt that many women in Kexel share. We are ignorant is a common sentiment among the women of Kexel, many of whom blame themselves for their lack of knowledge of what to do for a dying baby. Many women blame themselves for being uneducated. As a woman named Flora said, I have never been to school and I never learned about these things. Although monthly enrollment fees for public primary schools are low, school supplies, books, and uniforms are costly enough to deter many from sending their children to school. Most families with financial constraints educate sons before daughters, as an educated mans earning potential is greater than an educated womans.

Disturbingly, some womens interpretations of their ignorance reflect internalized racism. We are indigenous, so we do not know, they say. Because they are indigenous, they are also prone to experiencing racism in the hospital; many women fear ill treatment and say they have heard that babies go to the hospital only to die there. Another common reason women blame themselves is for a perceived lapse in emotional self-control. Recalling the death of her son Nelson, Dona Ramona commented that he probably died because of her bad milk. Nelsons infancy was a hard time for Ramona, whose husband had entered a period of alcoholism--a common escape for men who feel powerless under the yoke of oppressive poverty. When he drank, he would beat me, and I would get angry, she said, and they say that the anger goes with the milk to the child. Many other women suffering domestic violence and emotional abuse have mentioned the possibility of their uncontrolled emotions--grief, rage, and despair--killing their children both in the womb and through transfer of negativity into breast milk. Notably, women never blame a childs death on a husbands drinking or a beating itself. Rather, they perceive the death as their own failure to remain level-headed when confronted with severe stress. Women, as the subordinated half of an already oppressed population, are expected to calmly endure mistreatment from the more powerful and societally exalted men in their lives. Thus, the guilt mothers feel upon child death can reflect the sharp power differential between the sexes. Attribution of child death to ones ignorance or uncontrolled emotions allows a woman to imbue meaning to an incomprehensible situation; it also marks the self as the primary sufferer. However, as Tinas and Ramonas stories demonstrate, systemic problems of gender inequality, discrimination, and limited access to education form the basis of womens guilt. When women blame themselves for child mortality, they assume personal responsibility for a phenomenon

whose roots lie in political and economic inequalities.

Case Study 3: Blame in the Community Why me? Why have I lost so many children? Gloria frequently lamented. One day during the agricultural off-season, when her husband Elmer was despairing about not being able to find work and recalling all their past hardships, they offered an explanation to Glorias question: witchcraft. You dont know, they said in hushed voices, but our neighbors killed one of our little girls. They gestured to the house of Don Wiliam, who years ago had feuded with them over a small piece of land that connected their houses. Wiliams family, jealous that Elmers father had a few small plots of land for coffee farming, began to quarrel with the couple. During the conflict, Gloria had given birth to a beautiful chubby girl. When Wiliam saw the baby, he allegedly said, What a cute little girl, but lets see how long she lives. Within a few weeks, the baby died. Gloria and Elmer were devastated. The price they had paid for land they rightfully owned was the life of their beloved daughter, whom they believe had succumbed to a sickness sent by Wiliam. Although the interfamilial tensions over the piece of land eased out over the next few years, Gloria and Elmer inwardly harbor deep mistrust of their neighbors. They sometimes wonder if community members sent sicknesses upon the other children they have buried over the years. They are not alone in their suspicions of their neighbors. Many others in Kexel have similar interpretations of child loss. For example, after losing one child, a woman named Diana speculated uncertainly that the baby had been the victim of witchcraft. Years later, when her next babys health began to deteriorate, a witch confirmed Dianas suspicion that a jealous enemy had maliciously sent death upon her child. As Farmer (2006) writes, [the] obvious backdrop to sorceryis fierce competition in a

field of great scarcity (204). Any individual who is perceived to surpass the baseline of extreme poverty is subject to the envy of poorer counterparts. As Foster (1965) writes, a community member who gains upward mobility is perceived to do so at others expense. Witchcraft and fear of witchcraft function to ensure that everyone shares in the struggle of day-to-day living. It is also a powerful and compelling answer to Glorias question of why me? shared by so many mothers who have seen their children die. Witchcraft also defines the self as the victim and the accused as insiders. A suffering mother would not accuse just anyone of witchcraft--only one who belongs to her community and accordingly ought to share her socioeconomic status. Outsiders to the community are also outside the realm of blame and witchcraft. While witchcraft serves social and psychological functions, it is important to recognize how these accusations can be damaging to the community. Witchcraft makes community members turn on each other; it exacerbates conflicts between parties with long-standing tensions, and it creates conflicts where there is room for suspicion. As Glorias and Dianas stories show, witchcraft also keeps blame for child death circulating within the community. Poverty and the inaccessibility of health care services are absent from the picture, and again, community members are perceived to be at fault for child mortality.

Conclusion This paper has described how the blame associated with child death in Kexel is a manifestation of political economic conditions in Guatemala. It has also explored how discourses of blame serve social and psychological functions of coping with intense suffering and defining insiders, outsiders, and the self. One of the challenges of the analysis has been negotiating between the macro and micro

forces affecting cultural idioms of distress. Understanding womens experiences of child death certainly requires attention to the broader political context of poverty and discrimination--which Farmer (2004) refers to as structural violence. However, Scheper-Hughes (1992) concept of everyday violence, which Lockhart (2008) describes as routinized experiences of violence (96), is also germane. Lockhart exhorts us to focus on...the micro logics of power (2008:96). In Kexel, this could be a tryst with ones husband that causes emotional contamination; it could be a struggle with a neighbor over limited resources, manifesting as witchcraft directed against an enemys child. In either case, personal relationships shape womens interpretations of child mortality. Macro forces of gender inequality and poverty do shape these power dynamics, but the troubling nature of community members subjugating each other calls into mind Scheper-Hughes statement: How often the oppressed turn into their own oppressors, or worse still, into the oppressors of others! (1995:418). Although the origins of child death-associated blame are diffuse, all arrows strike one target: the community of Kexel. Whether the accusation is made by a medical practitioner or a resident of Kexel, fault lies in the hands of the victims: the community members and especially the mothers of Kexel. In analyzing womens narratives of child death in Kexel, we must ask ourselves why blame never leaves the community. As privileged outsiders, we are academically trained to analyze suffering in a framework of structural inequality. In the face of continual oppression, community members of Kexel are not empowered to interpret their problems in a broader context; the only power they have is over themselves and each other, and thus, they blame themselves and each other. This perspective, fostered by inequalities created by the state and global political economic system, frees the state and the world of responsibility to dying children. Thus, the

people of Kexel live with the myth that they are completely responsible for their childrens lives and deaths.

Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to the community of Kexel, and to Sarah Messmer, Shom Dasgupta, and Peter Rohloff, and Anne Kraemer for their collaboration in fieldwork and on this paper.

REFERENCES Farmer, Paul 2004 An Anthropology of Structural Violence (Sidney W. Mintz Lecture for 2001). Current Anthropology 3(45):305-325. 2006 Aids and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. Berkeley: University of California Press. Foster, George M. 1965 Peasant Society and the Image of Limited Good. American Anthropologist 67(2):293-315. Lockhart, Chris 2008 The Life and Death of a Street Boy in East Africa: Everyday Violence in the Time of AIDS. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 22(1):94-115. Pan American Health Organization 1998 Health in the Americas, Volumes 1-2. Washington, DC. Scheper-Hughes, Nancy 1992 Death without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1995 The Primacy of the Ethical: Propositions for a Militant Anthropology. Current Anthropology 36(1):409-420. World Health Organization 2006 Mortality Country Fact Sheet: Guatemala. World Health Statistics. Available online at: <http://www.who.int/countries/gtm/en>

You might also like

- Babylost: Racism, Survival, and the Quiet Politics of Infant Mortality, from A to ZFrom EverandBabylost: Racism, Survival, and the Quiet Politics of Infant Mortality, from A to ZNo ratings yet

- Lest We Forget: A Doctor's Experience with Life and Death During the Ebola OutbreakFrom EverandLest We Forget: A Doctor's Experience with Life and Death During the Ebola OutbreakNo ratings yet

- The Case for Birth Control: A Supplementary Brief and Statement of FactsFrom EverandThe Case for Birth Control: A Supplementary Brief and Statement of FactsNo ratings yet

- Spoilt Rotten: The Toxic Cult of SentimentalityFrom EverandSpoilt Rotten: The Toxic Cult of SentimentalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (23)

- Summary of Legacy by Uché Blackstock: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism in MedicineFrom EverandSummary of Legacy by Uché Blackstock: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism in MedicineNo ratings yet

- The First Breath: How Modern Medicine Saves the Most Fragile LivesFrom EverandThe First Breath: How Modern Medicine Saves the Most Fragile LivesNo ratings yet

- Reproducing Race: An Ethnography of Pregnancy as a Site of RacializationFrom EverandReproducing Race: An Ethnography of Pregnancy as a Site of RacializationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Catching a Case: Inequality and Fear in New York City's Child Welfare SystemFrom EverandCatching a Case: Inequality and Fear in New York City's Child Welfare SystemRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Breastfeeding, Subjugation and Empowerment in Rural GuatemalaDocument11 pagesBreastfeeding, Subjugation and Empowerment in Rural GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- The Children in Child Health: Negotiating Young Lives and Health in New ZealandFrom EverandThe Children in Child Health: Negotiating Young Lives and Health in New ZealandNo ratings yet

- Narrative of The Life and The Rights of Pregnant Women Behind Bars and The Custody Given To Their Newborn Child in PhilippinesDocument8 pagesNarrative of The Life and The Rights of Pregnant Women Behind Bars and The Custody Given To Their Newborn Child in PhilippinesFrances Camille Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Your Kids at Risk: How Teen Sex Threatens Our Sons and DaughtersFrom EverandYour Kids at Risk: How Teen Sex Threatens Our Sons and DaughtersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- American Red Cross Text-Book on Home Hygiene and Care of the SickFrom EverandAmerican Red Cross Text-Book on Home Hygiene and Care of the SickNo ratings yet

- Born in the USA: How a Broken Maternity System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children FirstFrom EverandBorn in the USA: How a Broken Maternity System Must Be Fixed to Put Women and Children FirstRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- Contradicting Maternity: HIV-positive motherhood in South AfricaFrom EverandContradicting Maternity: HIV-positive motherhood in South AfricaNo ratings yet

- You're Doing it Wrong!: Mothering, Media, and Medical ExpertiseFrom EverandYou're Doing it Wrong!: Mothering, Media, and Medical ExpertiseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Creative Research EssayDocument8 pagesCreative Research Essayapi-647791122No ratings yet

- A Doctor's Quest: The Struggle for Mother and Child Health Around the GlobeFrom EverandA Doctor's Quest: The Struggle for Mother and Child Health Around the GlobeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Maria DiscriminationDocument5 pagesMaria Discriminationapi-545938501No ratings yet

- Unstoppable: Forging the Path to Motherhood in the Early Days of IVFFrom EverandUnstoppable: Forging the Path to Motherhood in the Early Days of IVFNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Violence: Realities, and Resistance from Around the WorldFrom EverandObstetric Violence: Realities, and Resistance from Around the WorldNo ratings yet

- You're Teaching My Child What?: A Physician Exposes the Lies of Sex Education and How They Harm Your ChildFrom EverandYou're Teaching My Child What?: A Physician Exposes the Lies of Sex Education and How They Harm Your ChildRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- My Mother, Your Mother: What to Expect As Parents AgeFrom EverandMy Mother, Your Mother: What to Expect As Parents AgeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Pregnant While Black: Advancing Justice for Maternal Health in AmericaFrom EverandPregnant While Black: Advancing Justice for Maternal Health in AmericaNo ratings yet

- Let Me Tell You a Story: Inspirational Stories for Health, Happiness, and a Sexy WaistFrom EverandLet Me Tell You a Story: Inspirational Stories for Health, Happiness, and a Sexy WaistRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Maternity Death Road: Reproductive and Sexual HealthDocument30 pagesThe Maternity Death Road: Reproductive and Sexual HealthVedant TapadiaNo ratings yet

- Defiant Birth: Women Who Resist Medical EugenicsFrom EverandDefiant Birth: Women Who Resist Medical EugenicsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Not Our Kind of Girl: Unravelling the Myths of Black Teenage MotherhoodFrom EverandNot Our Kind of Girl: Unravelling the Myths of Black Teenage MotherhoodNo ratings yet

- Mother From Hell: Two Brothers, a Sadistic Mother, a Childhood Destroyed.From EverandMother From Hell: Two Brothers, a Sadistic Mother, a Childhood Destroyed.No ratings yet

- Bottled Up: How the Way We Feed Babies Has Come to Define Motherhood, and Why It Shouldn’tFrom EverandBottled Up: How the Way We Feed Babies Has Come to Define Motherhood, and Why It Shouldn’tRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- The Ebola Survival Handbook: An MD Tells You What You Need to Know Now to Stay SafeFrom EverandThe Ebola Survival Handbook: An MD Tells You What You Need to Know Now to Stay SafeNo ratings yet

- A City without Care: 300 Years of Racism, Health Disparities, and Health Care Activism in New OrleansFrom EverandA City without Care: 300 Years of Racism, Health Disparities, and Health Care Activism in New OrleansNo ratings yet

- Conceiving: Preventing and Treating InfertilityFrom EverandConceiving: Preventing and Treating InfertilityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Women and the Politics of Sterilization: A UNC Press Short, Excerpted from Choice and Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and WelfareFrom EverandWomen and the Politics of Sterilization: A UNC Press Short, Excerpted from Choice and Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and WelfareNo ratings yet

- This is How You Vagina: All About Your Vajayjay and Why You Probably Shouldn't Call it ThatFrom EverandThis is How You Vagina: All About Your Vajayjay and Why You Probably Shouldn't Call it ThatNo ratings yet

- Getting Ready to be a Mother: A Little Book of Information and Advice for the Young Woman Who is Looking Forward to MotherhoodFrom EverandGetting Ready to be a Mother: A Little Book of Information and Advice for the Young Woman Who is Looking Forward to MotherhoodNo ratings yet

- SP Reasearch PaperDocument11 pagesSP Reasearch Paperapi-456576310No ratings yet

- Pregnancy in Practice: Expectation and Experience in the Contemporary USFrom EverandPregnancy in Practice: Expectation and Experience in the Contemporary USNo ratings yet

- Cracks in Motherhood: Study of Maternal Depression Among LatinasFrom EverandCracks in Motherhood: Study of Maternal Depression Among LatinasNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Suffering and The Goals of NursingDocument140 pagesThe Nature of Suffering and The Goals of NursingGusni FitriNo ratings yet

- Major Challenges To Scale Up of Visual Inspection-Based Cervical Cancer Prevention Programs: The Experience of Guatemalan NGOsDocument11 pagesMajor Challenges To Scale Up of Visual Inspection-Based Cervical Cancer Prevention Programs: The Experience of Guatemalan NGOsWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Mixed-Methods Study Identifies Key Strategies For Improving Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices in A Highly Stunted Rural Indigenous Population in GuatemalaDocument16 pagesMixed-Methods Study Identifies Key Strategies For Improving Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices in A Highly Stunted Rural Indigenous Population in GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- The Normalization of Childhood Disease: An Ethnographic Study of Child Malnutrition in Rural GuatemalaDocument11 pagesThe Normalization of Childhood Disease: An Ethnographic Study of Child Malnutrition in Rural GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- More Than Words: Towards A Development-Based Approach To Language RevitalizationDocument17 pagesMore Than Words: Towards A Development-Based Approach To Language RevitalizationWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- The Changing Role of Indigenous Lay Midwives in Guatemala: New Frameworks For AnalysisDocument7 pagesThe Changing Role of Indigenous Lay Midwives in Guatemala: New Frameworks For AnalysisWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding, Subjugation and Empowerment in Rural GuatemalaDocument11 pagesBreastfeeding, Subjugation and Empowerment in Rural GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Examining The Social Contract Through Child Nutrition in GuatemalaDocument18 pagesExamining The Social Contract Through Child Nutrition in GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Technical Report - STIs and Women's Health in Rural Guatemalan CommunitiesDocument5 pagesTechnical Report - STIs and Women's Health in Rural Guatemalan CommunitiesWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Determining Adult Type 2 Diabetes-Related Health Care Needs in An Indigenous Population From Rural Guatemala: A Mixed-Methods Preliminary StudyDocument11 pagesDetermining Adult Type 2 Diabetes-Related Health Care Needs in An Indigenous Population From Rural Guatemala: A Mixed-Methods Preliminary StudyWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Determining Adult Type 2 Diabetes-Related Health Care Needs in An Indigenous Population From Rural Guatemala: A Mixed-Methods Preliminary StudyDocument11 pagesDetermining Adult Type 2 Diabetes-Related Health Care Needs in An Indigenous Population From Rural Guatemala: A Mixed-Methods Preliminary StudyWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- The Global Burden of Diabetes: Case Studies From GuatemalaDocument37 pagesThe Global Burden of Diabetes: Case Studies From GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- The Intersection of Language, Culture, and Medicine in GuatemalaDocument15 pagesThe Intersection of Language, Culture, and Medicine in GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- The Normalization of Childhood Disease: An Ethnographic Study of Child Malnutrition in Rural GuatemalaDocument11 pagesThe Normalization of Childhood Disease: An Ethnographic Study of Child Malnutrition in Rural GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2012Document16 pagesAnnual Report 2012Wuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Report On Community C1 - Progress in Child Malnutrition ProgramingDocument3 pagesReport On Community C1 - Progress in Child Malnutrition ProgramingWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Tweet: Visible Voices & TechDocument70 pagesIndigenous Tweet: Visible Voices & TechWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Sustaining DonorsDocument2 pagesSustaining DonorsWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Against Handmaiden Humanism: The Case of The 2009 Gold Foundation Humanism in Medicine' Essay ContestDocument6 pagesAgainst Handmaiden Humanism: The Case of The 2009 Gold Foundation Humanism in Medicine' Essay ContestWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- "Beyond Development": A Critical Appraisal of The Emergence of Small Health Care Non-Governmental Organizations in Rural GuatemalaDocument11 pages"Beyond Development": A Critical Appraisal of The Emergence of Small Health Care Non-Governmental Organizations in Rural GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Language Revitalization and The Problem of Development in Guatemala: Case Studies From Health CareDocument16 pagesLanguage Revitalization and The Problem of Development in Guatemala: Case Studies From Health CareWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Agua Potable - Potable WaterDocument2 pagesAgua Potable - Potable WaterWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Nutritional ProgramsDocument2 pagesNutritional ProgramsWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Male Influence On Infant Feeding in Rural Guatemala and Implications For Child Nutrition Interventions.Document6 pagesMale Influence On Infant Feeding in Rural Guatemala and Implications For Child Nutrition Interventions.Wuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Liberation Theology and The Indigenous Other in GuatemalaDocument3 pagesLiberation Theology and The Indigenous Other in GuatemalaWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- DiabetesDocument2 pagesDiabetesWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- "So That We Don't Lose Words:" Reconstructing A Kaqchikel Medical LexiconDocument12 pages"So That We Don't Lose Words:" Reconstructing A Kaqchikel Medical LexiconWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Programs - PosterDocument1 pageNutrition Programs - PosterWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Programs - PosterDocument1 pageNutrition Programs - PosterWuqu' KawoqNo ratings yet

- The Scope and Development of Political SociologyDocument4 pagesThe Scope and Development of Political SociologyshriyaNo ratings yet

- EurasianStudies 0309Document164 pagesEurasianStudies 0309goran jovicevicNo ratings yet

- Order of Nine Angles - Interview With Vilnius ThornianDocument4 pagesOrder of Nine Angles - Interview With Vilnius Thorniannoctulius_moongod6002No ratings yet

- The Bird Man: What Bird Was Its Inspiration?Document6 pagesThe Bird Man: What Bird Was Its Inspiration?Alex Moore-MinottNo ratings yet

- Disease and Health - ReadingsDocument7 pagesDisease and Health - ReadingsCoursePin100% (1)

- 1979 - Van MaanenDocument13 pages1979 - Van MaanenFNo ratings yet

- Eclectic Method and Communication Theory The Jam Session As The New SymposiumDocument1 pageEclectic Method and Communication Theory The Jam Session As The New SymposiumVictor RoundjazzNo ratings yet

- Towards A Theology of ArtsDocument10 pagesTowards A Theology of ArtsAndréNo ratings yet

- The Trinity, Creation, and Christian AnthropologyDocument4 pagesThe Trinity, Creation, and Christian AnthropologyDomingo García GuillénNo ratings yet

- Critical Review of Communication in Business JournalsDocument9 pagesCritical Review of Communication in Business Journalssukmay24No ratings yet

- Educational Research Step - 2..Document26 pagesEducational Research Step - 2..lorenaNo ratings yet

- ANT101!21!22 Research Method Ethnography NNDocument27 pagesANT101!21!22 Research Method Ethnography NNmim.naushikamahmudNo ratings yet

- Material CultureDocument7 pagesMaterial CultureGost hunterNo ratings yet

- 2010 Apocalypse BoschDocument23 pages2010 Apocalypse BoschAshli Kingfisher100% (1)

- Imaging Indigenous Children in Selected Philippine Children's StoriesDocument28 pagesImaging Indigenous Children in Selected Philippine Children's StoriesLui BrionesNo ratings yet

- What Is AnthropologyDocument20 pagesWhat Is AnthropologyRaissa AngeloNo ratings yet

- BL Epic 1.0 ChecklistDocument3 pagesBL Epic 1.0 ChecklistAnonymous idrxjdzNo ratings yet

- Critical AnthropologyDocument25 pagesCritical AnthropologyBenny Apriariska Syahrani100% (1)

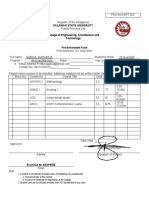

- PSU-ACA-EAT-023 Pre-Enrolment FormDocument2 pagesPSU-ACA-EAT-023 Pre-Enrolment FormSiahara GarciaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Study of Religion (Starter)Document4 pagesIntroduction To The Study of Religion (Starter)oollaasszzNo ratings yet

- Causes of War CourseDocument6 pagesCauses of War CourseNicolas TerradasNo ratings yet

- Anastopoulou Et Al (2017) - Statistical Method Reassociating Human Tali and Calcanei From Commingled ContextDocument5 pagesAnastopoulou Et Al (2017) - Statistical Method Reassociating Human Tali and Calcanei From Commingled ContextAlexandrosNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Anthropology of ViolenceDocument2 pagesRethinking Anthropology of ViolenceGraziele DaineseNo ratings yet

- Gods and Mortals CornerstonesDocument3 pagesGods and Mortals CornerstonesLoriNo ratings yet

- A New Paradigm For The Sociology of ChildhoodDocument15 pagesA New Paradigm For The Sociology of ChildhoodEme NascimentoNo ratings yet

- Language Universals and Linguistic Typology - Presentation PDFDocument18 pagesLanguage Universals and Linguistic Typology - Presentation PDFLukas ZbindenNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 The Nature of The Human PersonDocument33 pagesLesson 3 The Nature of The Human PersonIan Pardico100% (3)

- Introduction To The AlchemistDocument21 pagesIntroduction To The AlchemistNamrata Jain100% (2)

- Absence of Mind: The Dispelling of Inwardn - Marilynne RobinsonDocument180 pagesAbsence of Mind: The Dispelling of Inwardn - Marilynne RobinsonTim Tom100% (4)

- Patricia Riles Wickman - The Tree That Bends - Discourse, Power, and The Survival of Maskoki People-University Alabama Press (1999)Document317 pagesPatricia Riles Wickman - The Tree That Bends - Discourse, Power, and The Survival of Maskoki People-University Alabama Press (1999)Paul0% (1)