Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pitching High Gravity Wort

Uploaded by

Jesso GeorgeOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pitching High Gravity Wort

Uploaded by

Jesso GeorgeCopyright:

Available Formats

PITCHING HIGH-GRAVITY WORTS

Q: What are your recommendations for pitching high-gravity brews? I had a 1.109 wort that was well-aerated and pitched with a big (1.5-L) healthy American ale yeast starter. I racked to secondary once the visibly active fermentation had subsided (one week). The gravity was down to 1.060 - a pretty respectable drop, but still nowhere near the appropriate 1.025-1.030 terminal gravity. I know that Champagne yeasts are more alcoholtolerant, and I have used them before, but I wanted to try an ale yeast. I am aware that many brewers pitch additional yeast to remedy a stuck fermentation (or sometimes by design). That practice, however, raises some questions (I posed the question to the internet mailing list Home Brew Digest and still had some unanswered questions). Although vigorous aeration is appropriate for pitching unfermented wort, in a partially fermented beer it is just asking for trouble because of oxidation. It would seem, then, that the volume of additional yeast would need to be large, but how large? What about aerating the starter before pitching the additional yeast into the secondary? Is that introduction of oxygen going to be a problem, or will the yeast consume it without ill effect? If you don't aerate the starter, will the largely anaerobic conditions lead to off-flavors when the new yeast gets to work? Obviously, I have already done something long before this ever makes it into print, but I imagine that many readers will find your response useful. (I pitched an aerated 750-mL starter of the same Chico yeast into the unaerated 1.060 beer and will have to wait for the results.) DM: I have no first-hand experience with worts as heavy as yours. The strongest ales I have ever made were barley wines with original gravities in the mid-1.080s. I pitched these with Chico ale yeast (Wyeast #1056, the same strain you are using) and fermented to a terminal gravity of about 1.020. This experience would indicate that you are right in assuming that there is a problem with your fermentation; your wort dropped only (!) 49 points before the yeast pooped out, whereas mine dropped at least 60. The usual problem with using brewing yeasts for very strong beers is that many of the brewing strains have limited alcohol tolerance. I have heard tales of ale yeasts that cannot take more than 5% alcohol before they pass out like a giddy maiden. However, as my experience proves, Chico is not one of these faint-hearted yeast strains. It should have been able to ferment your wort down farther. No question, though, that a strong fermentation demands young, healthy yeast cells in top physical condition. This is why wort aeration is so important. Your yeast needs to grow before it starts to ferment. Most of the cells in the wort need to be young and fresh - not old cells that are already tired from having gone through a fermentation before. Several factors can lead to a weak fermentation. Note that the effect of these factors will be magnified when you work with heavy wort. In a normal-gravity wort, they might pass unnoticed or manifest themselves only in a slightly prolonged fermentation.

The first factor is wort aeration. You sound like a person who is very concerned about oxidation and may be reluctant to aerate your wort. Don't be. Wort must be saturated with air either before or immediately after pitching. If you get a stuck fermentation and decide to repitch, aerate again - the wort as well as the starter. The most likely result of reaeration will be an increased level of diacetyl in the finished beer, but at this point you're doing a salvage operation and your choice may be between flawed beer and no beer. Besides, diacetyl is not necessarily a fault in barley wine. A second factor in weak fermentations is over- or underpitching. Most home brewers by now are aware of underpitching, but overpitching can also lead to similar problems. If you overpitch, the yeast does not grow as much, so you end up with more old, tired cells and fewer young, healthy ones. This may pass unnoticed in beers of normal gravity, but in a wort as heavy as yours, it may easily lead to a stuck fermentation; remember, normalgravity worts, in fermenting out, don't drop as far as your wort did before it stuck. You don't state your batch volume, but if it is 5 gal, then a 1.5-L starter, depending on how it was made, may be too much. A third factor in weak fermentations is the Crabtree effect, which was first brought to the attention of home brewers by George Fix. Yeast has such an affinity for glucose that, if a solution (such as wort) contains more than about 1% of it, the cells will immediately begin to ferment it - even if oxygen is available for respiration and growth. In other words, the practical effect of high glucose levels is to short-circuit the normal growth of the yeast in the pitched wort. A very high gravity wort is more likely to have a lot of glucose in it especially if it is made up entirely or partly from high-glucose malt extract or if sugar has been used to boost the gravity. You don't say how your wort was made, but you can judge for yourself how likely the wort composition is to be a factor in your problem. For the sake of completeness, I should mention that lack of yeast nutrients is another cause of stuck fermentations, but a wort of such high gravity is almost certain to contain enough amino acids, vitamins, and minerals for good yeast growth. Good luck with your repitch. Let me know how you make out.

You might also like

- Home Brewing: 70 Top Secrets & Tricks To Beer Brewing Right The First Time: A Guide To Home Brew Any Beer You Want (With Recipe Journal)From EverandHome Brewing: 70 Top Secrets & Tricks To Beer Brewing Right The First Time: A Guide To Home Brew Any Beer You Want (With Recipe Journal)No ratings yet

- Is Your Wort Cool Enough For Happy Yeast?Document2 pagesIs Your Wort Cool Enough For Happy Yeast?RiyanNo ratings yet

- Make Yeast StarterDocument2 pagesMake Yeast StarterAlexandraNo ratings yet

- Home Brewing: 70 Top Secrets & Tricks To Beer Brewing Right The First Time: A Guide To Home Brew Any Beer You WantFrom EverandHome Brewing: 70 Top Secrets & Tricks To Beer Brewing Right The First Time: A Guide To Home Brew Any Beer You WantNo ratings yet

- Down To The Root - Make Your Own Root BeerDocument16 pagesDown To The Root - Make Your Own Root BeerjohodadaNo ratings yet

- Step by Step Guide To Making Red Wine From GrapesDocument3 pagesStep by Step Guide To Making Red Wine From Grapescyrano8559No ratings yet

- The Homebrewer's Handbook: An Illustrated Beginner?s GuideFrom EverandThe Homebrewer's Handbook: An Illustrated Beginner?s GuideNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Blending Yeast StrainsDocument25 pagesA Guide To Blending Yeast StrainsGiba BarrosNo ratings yet

- Apple Cider Vinegar for Health and Beauty: Recipes for Weight Loss, Clear Skin, Superior Health, and Much More?the Natural WayFrom EverandApple Cider Vinegar for Health and Beauty: Recipes for Weight Loss, Clear Skin, Superior Health, and Much More?the Natural WayNo ratings yet

- Dukes of Ale BJCP Preparation Course Yeast and FermentationDocument6 pagesDukes of Ale BJCP Preparation Course Yeast and FermentationMilito GilbertoNo ratings yet

- Brewer Prepare Like an Expert: Over 600 Thirst Quenching Beer Recipes!From EverandBrewer Prepare Like an Expert: Over 600 Thirst Quenching Beer Recipes!No ratings yet

- A Beginner's Guide To BeermakingDocument7 pagesA Beginner's Guide To BeermakingShaheer MuhammadNo ratings yet

- The Joy of Brewing Cider, Mead, and Herbal Wine: How to Craft Seasonal Fast-Brew Favorites at HomeFrom EverandThe Joy of Brewing Cider, Mead, and Herbal Wine: How to Craft Seasonal Fast-Brew Favorites at HomeNo ratings yet

- Sour Beer PresentationDocument23 pagesSour Beer PresentationMarlon RebelloNo ratings yet

- Time for Divine Wine: Simple Guide to Wine Making, Wine Tasting and Wine Serving Your Homemade Vintage: Homemade Wine Recipes, Guide to Making Wine at HomeFrom EverandTime for Divine Wine: Simple Guide to Wine Making, Wine Tasting and Wine Serving Your Homemade Vintage: Homemade Wine Recipes, Guide to Making Wine at HomeNo ratings yet

- Homebrewing: A Short Intro To Great Hobby by Richard Rarkin Smashwords EditionDocument4 pagesHomebrewing: A Short Intro To Great Hobby by Richard Rarkin Smashwords EditionJohn PapNo ratings yet

- Fruit Wine: S W I MDocument4 pagesFruit Wine: S W I MJames WhiteNo ratings yet

- The Beginner's Guide to Beer Brewing: Fundamentals Of Beer BrewingFrom EverandThe Beginner's Guide to Beer Brewing: Fundamentals Of Beer BrewingNo ratings yet

- Applewine PDFDocument2 pagesApplewine PDFBuruh PabrikNo ratings yet

- Apple Wine RecipeDocument2 pagesApple Wine RecipeFred smithNo ratings yet

- 10 Steps To Better Extract BrewingDocument3 pages10 Steps To Better Extract BrewingmykkramerNo ratings yet

- Yeast and Starters PDFDocument7 pagesYeast and Starters PDFOrlando GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Pineapple WineDocument17 pagesPineapple WineBea Irish LubaoNo ratings yet

- SoCo Almond Coconut Stout All Grain Recipe InstructionsDocument2 pagesSoCo Almond Coconut Stout All Grain Recipe InstructionsJavier OrozcoNo ratings yet

- YeastStarter PDFDocument6 pagesYeastStarter PDFHiran GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Brewing ProcessDocument34 pagesBrewing ProcessDiana Mdm100% (1)

- Beginners Guide To Small Batch Home Brewing 5 PDFDocument34 pagesBeginners Guide To Small Batch Home Brewing 5 PDFGuha KashyapNo ratings yet

- How To Make Wine From JuiceDocument16 pagesHow To Make Wine From Juicealex_077100% (1)

- 6 Beginner Mead MistakesDocument6 pages6 Beginner Mead Mistakesryder grayNo ratings yet

- Making Organic Wine at HomeDocument26 pagesMaking Organic Wine at HomeSheryl100% (2)

- KK Beer Guide Booklet 091522 Print Ready - Small-MinDocument12 pagesKK Beer Guide Booklet 091522 Print Ready - Small-MinClifton SutherlandNo ratings yet

- There's A Sulfur Smell in My Wine!Document9 pagesThere's A Sulfur Smell in My Wine!Anonymous ePcnZoBENo ratings yet

- Yeast Life Cycle PDFDocument2 pagesYeast Life Cycle PDFMax CrawfordNo ratings yet

- Frozen Concentrate Wine: IngredientsDocument2 pagesFrozen Concentrate Wine: IngredientssergeiivanNo ratings yet

- Artisan Home Distilling: Capturing Summer's FlavorsDocument5 pagesArtisan Home Distilling: Capturing Summer's Flavorsjeej00No ratings yet

- Standard Fruit Wine Recipe GuideDocument3 pagesStandard Fruit Wine Recipe GuidechadNo ratings yet

- Rec.crafts.brewing FAQ: Answers for homebrewing questionsDocument10 pagesRec.crafts.brewing FAQ: Answers for homebrewing questionsSajid FarooqNo ratings yet

- The Brewer's Apprentice+OCRDocument193 pagesThe Brewer's Apprentice+OCRRena Roca100% (9)

- Aussie Homebrewer'S Guide To The Galaxy and BeyondDocument10 pagesAussie Homebrewer'S Guide To The Galaxy and BeyondDaniel EmersonNo ratings yet

- A Beginner's GUIDE To Wine MakingDocument2 pagesA Beginner's GUIDE To Wine Makingzaratustra21No ratings yet

- 10 Steps Successful FermentationDocument4 pages10 Steps Successful FermentationVictor SáNo ratings yet

- How to Make Organic Wine at HomeDocument30 pagesHow to Make Organic Wine at HomeMike FelgenNo ratings yet

- Off FlavorsDocument9 pagesOff FlavorspetikissNo ratings yet

- Fermentation of WineDocument5 pagesFermentation of WineskljoleNo ratings yet

- Winemaking Presentation For Welca Fall GatheringDocument21 pagesWinemaking Presentation For Welca Fall Gatheringapi-286688960No ratings yet

- Hidromiel BebidasDocument14 pagesHidromiel BebidasRuben 867No ratings yet

- 2 Distillation Proof System1Document5 pages2 Distillation Proof System1Ketan ChandeNo ratings yet

- Wine Folly The Essential Guide To Wine PDocument481 pagesWine Folly The Essential Guide To Wine PMario Alfageme0% (2)

- Plum Wine: IngredientsDocument2 pagesPlum Wine: IngredientsLagusNo ratings yet

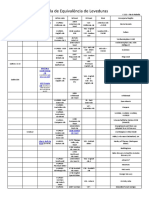

- Equivalencias Levaduras Liquidas-Secas PDFDocument2 pagesEquivalencias Levaduras Liquidas-Secas PDFMaxi OhanNo ratings yet

- 5 Gallon Kit: Using Steeping Grains Brewing With Extract Fermentation BottlingDocument28 pages5 Gallon Kit: Using Steeping Grains Brewing With Extract Fermentation BottlingSurendra Ramkissoon100% (1)

- Wine Folly - The Essential Guide To Wine PDFDocument481 pagesWine Folly - The Essential Guide To Wine PDFLaura VM23% (39)

- Yeast StarterDocument1 pageYeast StartersupersugerNo ratings yet

- 1 Gallon Mead Recipe For Beginners - Easy Mead Recipe & KiDocument5 pages1 Gallon Mead Recipe For Beginners - Easy Mead Recipe & KiRyanNo ratings yet

- How To Make Your Own Red Dragon Fruit WineDocument8 pagesHow To Make Your Own Red Dragon Fruit WineShakura Ahseyia0% (1)

- All About Distillers Yeast and Turbo Yeast - VGR DistributingDocument6 pagesAll About Distillers Yeast and Turbo Yeast - VGR DistributingarjunanpnNo ratings yet

- Yeast PDFDocument10 pagesYeast PDFBianca CotellessaNo ratings yet

- 10 Steps To Better Extract Brewing.Document3 pages10 Steps To Better Extract Brewing.Manzini MlebogengNo ratings yet

- Wyeast NutrientDocument1 pageWyeast NutrientJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Root Beer ConcentrateDocument15 pagesRoot Beer ConcentrateJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Northern India Pale AleDocument1 pageNorthern India Pale AleJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- The Care and Feeding of A CorneliusDocument3 pagesThe Care and Feeding of A CorneliusJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Midwest Honeybee AleDocument2 pagesMidwest Honeybee AleJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- ST Pats Counterpressure Bottle FillerDocument1 pageST Pats Counterpressure Bottle FillerJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- White Lab Inst For StarterDocument2 pagesWhite Lab Inst For StarterJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Super High Gravity AleDocument1 pageSuper High Gravity AleJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Shawn's IPADocument1 pageShawn's IPAJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Octane IPADocument2 pagesOctane IPAJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Percent Alcohol ChartDocument3 pagesPercent Alcohol ChartJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Making A Yeast StarterDocument1 pageMaking A Yeast StarterErick El Pinche ZurdoNo ratings yet

- Midwest CatalogDocument48 pagesMidwest CatalogJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- JB's IPADocument1 pageJB's IPAJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Joe's IPADocument1 pageJoe's IPAJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- JB's Best India AleDocument2 pagesJB's Best India AleJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Kraeusening Your BeerDocument1 pageKraeusening Your BeerJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Java StoutDocument2 pagesJava StoutJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Inst Brew SpreadsheetDocument6 pagesInst Brew SpreadsheetJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Hops Use ChartDocument3 pagesHops Use ChartJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- India Pale AleDocument8 pagesIndia Pale AleJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Grains and Adjuncts ChartDocument2 pagesGrains and Adjuncts ChartJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- India Pale Al1Document9 pagesIndia Pale Al1Jesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Homebrew LabDocument6 pagesHomebrew LabJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Discover The Joys of KeggingDocument8 pagesDiscover The Joys of KeggingJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Hot Chili BeerDocument5 pagesHot Chili BeerJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Eight Tips To Advance Your Brewing SkillsDocument5 pagesEight Tips To Advance Your Brewing SkillsJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Dry Hopping RecommendationsDocument2 pagesDry Hopping RecommendationsJesso GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Chart of Accounts List: AssetsDocument18 pagesChart of Accounts List: AssetsGlen JavellanaNo ratings yet

- Notice de Réparation RI9724 - 02 PDFDocument224 pagesNotice de Réparation RI9724 - 02 PDFBaciu NicolaeNo ratings yet

- New Belgium BrochureDocument2 pagesNew Belgium Brochureapi-271084906No ratings yet

- Brewhouse Sizing PDFDocument166 pagesBrewhouse Sizing PDFFEDESORENNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Enzymatic and Precipitation Treatments For Glutenfree Craft Beers ProductionDocument28 pagesComparison of Enzymatic and Precipitation Treatments For Glutenfree Craft Beers ProductionCris LopesNo ratings yet

- Spring 2013 Independent Publishers Group General TradeDocument212 pagesSpring 2013 Independent Publishers Group General TradeIndependent Publishers GroupNo ratings yet

- User Manual en Software BrewtargetDocument25 pagesUser Manual en Software BrewtargetGustavo RuasNo ratings yet

- Barley Grain: Feed Industry GuideDocument36 pagesBarley Grain: Feed Industry GuideYusrita DewiNo ratings yet

- Beer MenuDocument1 pageBeer MenueatlocalmenusNo ratings yet

- Food Ingredients and Their Halal StatusDocument121 pagesFood Ingredients and Their Halal StatusMuslim Consumer Group90% (10)

- Larba Minch University: Arba Minch University Arba Minch Institute of Technology Department of Mechanical EngineeringDocument77 pagesLarba Minch University: Arba Minch University Arba Minch Institute of Technology Department of Mechanical Engineeringmengstuhagos1223No ratings yet

- 105 MRP of Brand DetailsDocument128 pages105 MRP of Brand DetailsAarti A BhardwajNo ratings yet

- How to modify beer flavor and colour using malt extractsDocument1 pageHow to modify beer flavor and colour using malt extractsAnonymous hP6ab2D1ppNo ratings yet

- Types of BeveragesDocument35 pagesTypes of Beveragesedcel boberNo ratings yet

- CLOZE TEST 2 (40 ADET SORUDocument11 pagesCLOZE TEST 2 (40 ADET SORUFurkan OkumusogluNo ratings yet

- Corona Beer Industry Trends and Modelo's International ExpansionDocument7 pagesCorona Beer Industry Trends and Modelo's International Expansionfbl3No ratings yet

- By, Kunjal Patel, M.sc. Microbiology .Document30 pagesBy, Kunjal Patel, M.sc. Microbiology .gaurangHpatelNo ratings yet

- Catalogo BestmalzDocument36 pagesCatalogo BestmalzjadriazolaNo ratings yet

- Cumplimiento Uen Semana 48Document14 pagesCumplimiento Uen Semana 48Javier Carvajal AguilarNo ratings yet

- Hydranautics - Nitto Membrane Applications, Case Studies, Lessons LearntDocument37 pagesHydranautics - Nitto Membrane Applications, Case Studies, Lessons Learntkalyan patilNo ratings yet

- 2013-11705-01 Brewing Handbook Final SpreadsDocument63 pages2013-11705-01 Brewing Handbook Final SpreadsCheverry Beer80% (5)

- Headway GiftingDocument14 pagesHeadway Giftinganonymous bloggerNo ratings yet

- Tabela Equivalência Leveduras Cervejeiras PDFDocument3 pagesTabela Equivalência Leveduras Cervejeiras PDFFelipe DonatNo ratings yet

- Cerevisia: Hubert Verachtert, Guy DerdelinckxDocument8 pagesCerevisia: Hubert Verachtert, Guy DerdelinckxPipo PescadorNo ratings yet

- Group Case AnalysisDocument4 pagesGroup Case AnalysisHannah Jean86% (7)

- Bread and PastryDocument36 pagesBread and PastryAvi MunchkinNo ratings yet

- Factors of Production & Utility DefinedDocument22 pagesFactors of Production & Utility DefinedJomoshNo ratings yet

- FMCG Group 1Document52 pagesFMCG Group 121324jesikaNo ratings yet

- Beer Brewing PowerpointDocument23 pagesBeer Brewing Powerpointapi-286688960100% (1)

- Ginger Ale Verses BeerDocument9 pagesGinger Ale Verses BeerSwami AbhayanandNo ratings yet