Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cool Print

Uploaded by

isabel-sherwin-fernandez-2383Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cool Print

Uploaded by

isabel-sherwin-fernandez-2383Copyright:

Available Formats

SILVERIO VS.

REPUBLIC Facts: Rommel Silverio filed a petition for the change of his gender and first name in his birth certificate to facilitate his marriage with his fianc. A year before, Silverio has underwent sex re-assignment surgery in Bangkok, Thailand. In his petition, he wants to change his first name from Rommel to Mely. Should the court allow the changeof name? ANSWER: No. The SC said that considering that there is no law recognizing sex re-assignment, the determination of a persons sex at the time of birth, if not attended by error, is immutable. It held that while petitioner may have succeeded in altering his body and appearance through the intervention of modern surgery, no law authorizes the change of entry as to sex in the civil registry for that reason. There is no special law in the country governing sex reassignment and its effect. (visit fellester.blogspot.com) This is fatal to petitioners cause. The Court said that the change in gender sought by petitioner will have serious and wide-ranging legal and public policy consequences, i.e., substantially reconfigure and greatly alter the laws on marriage and family relations and substantially affect the public policy in relation to women in laws such as the provisions of the Labor Code on employment of women, certain felonies under the Revised Penal Code, etc.

REPUBLIC VS. CAGANDAHAN This could be the first case that was decided under Philippine jurisprudence with such unique facts. The author first heard it in the news and decided to make a digested case of the same. However, the Philippine Supreme Court has no complete record of the case yet online. Despite that the author made use of available online facts provided by the Supreme Court and made it possible to come up with the case digest below.

FACTS: Jennifer Cagandahan filed before the Regional Trial Court Branch 33 of Siniloan, Laguna a Petition for Correction of Entries in Birth Certificate of her name from Jennifer B. Cagandahan to Jeff Cagandahan and her gender from female to male. It appearing that Jennifer Cagandahan is suffering from Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia which is a rare medical condition where afflicted persons possess both male and female characteristics. Jennifer Cagandahan grew up with secondary male characteristics. To further her petition, Cagandahan presented in court the medical certificate evidencing that she is suffering from Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia which certificate is issued by Dr. Michael Sionzon of the Department of Psychiatry, University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital, who, in addition, explained that "Cagandahan genetically is female but because her body secretes male hormones, her female organs did not develop normally, thus has organs of both male and female." The lower court decided in her favor but the Office of the Solicitor General appealed before the Supreme Court invoking that the same was a violation of Rules 103 and 108 of the Rules of Court because the said petition did not implead the local civil registrar. RULING: The Supreme Court affirmed the decision of the lower court. It held that, in deciding the case, the Supreme Court considered the compassionate calls for recognition of the various degrees of intersex as variations which should not be subject to outright denial. The Supreme Court made use of the availale evidence presented in court including the fact that private respondent thinks of himself as a male and as to the statement made by the doctor that Cagandahan's body produces high levels of male hormones (androgen), which is preponderant biological support for considering him as being male. The Supreme Court further held that they give respect to (1) the diversity of nature; and (2) how an individual deals with what nature has handed out. That is, the Supreme Court respects the respondents congenital condition

and his mature decision to be a male. Life is already difficult for the ordinary person. The Court added that a change of name is not a matter of right but of judicial discretion, to be exercised in the light of the reasons and the consequences that will follow.

TECSON VS. COMELEC FACTS: The case at bar is a consolidated case filed by petitioners questioning the certificate of candidacy of herein private respondent Ronald Allan Kelly Poe also known as Fernando Poe, Jr. The latter filed his certificate of candidacy for the position of President of the Philippines under the Koalisyon ng Nagkakaisang Pilipino (KNP) party. He represented himself in said certificate as a natural-born citizen of the Philippines, which reason that petitioners filed a petition before the Comelec to disqualify private respondent Fernando Poe, Jr. and to deny due course or to cancel his certificate of candidacy on the ground that the latter made a material misrepresentation in his certificate of candidacy by claiming to be a natural-born Filipino when in truth his parents were foreigners and he is an illegitimate child. The Comelec dismissed the petition. Hence, this appeal.

ISSUE: The controversy in the case at bar centers on the citizenship of Fernando Poe, Jr. as to whether or not he is a natural-born citizen of the Philippines.

RULING: Before discussing on the issue at hand it is worth stressing that since private respondent Fernando Poe, Jr. was born on August 20, 1939, the applicable law then controlling was the 1935 constitution. The issue on private respondents citizenship is so essential in view of the constitutional provision that, No person may be elected President unless he is a natural-born citizen of the Philippines, a registered voter, able to read and write, at least forty years of age on the day of the election, and a resident of the Philippines for at least ten years immediately preceding such election. Natural-born citizens are those who are citizens of the Philippines from birth without having to perform any act to acquire or perfect their Philippine citizenship. Based on the evidence presented which the Supreme consider as viable is the fact that the death certificate of Lorenzo Poe, father of Allan Poe, who in turn was the father of private respondent Fernando Poe, Jr. indicates that he died on September 11, 1954 at the age of 84 years, in San Carlos, Pangasinan. Evidently, in such death certificate, the residence of Lorenzo Poe was stated to be San Carlos, Pangansinan. In the absence of any evidence to the contrary, it should be sound to conclude, or at least to presume, that the place of residence of a person at the time of his death was also his residence before death. Considering that the allegations of petitioners are not substantiated with proof and since Lorenzo Poe may have been benefited from the en masse Filipinization that the Philippine Bill had effected in 1902, there is no doubt that Allan Poe father of private respondent Fernando Poe, Jr. was a Filipino citizen. And, since the latter is governed by the provisions of the 1935 Constitution which constitution considers as citizens of the Philippines those whose fathers are citizens of the Philippines, Fernando Poe, Jr. was in fact a natural-born citizen of the Philippines regardless of whether or not he is legitimate or illegitimate.

KILOSBAYAN VS ERMITA Only natural-born Filipino citizens may be appointed as justice of the Supreme Court Decision of administrative body (Bureau of Immigration) declaring one a natural-born citizen is not binding upon the courts when there are circumstances that entail factual assertions that need to be threshed out in proper judicial proceedings

FACTS: This case arose when respondent Gregory S. Ong was appointed by Executive Secretary, in representation of the Office of the President, as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Petitioners contended that respondent Ong is a Chinese citizen, born on May 25, 1953 to Chinese parents. They further added that even if it were granted that eleven years after respondent Ong's birth, his father was finally granted Filipino citizenship by naturalization, that, by itself, would not make respondent Ong a natural-born citizen. For his part, respondent Ong contended that he is a natural-born citizen and presented a certification from the Bureau of Immigration and the DOJ declaring him to be such. ISSUE: Whether or not respondent Ong is a natural-born Filipino citizen RULING: xxx respondent Ong is a naturalized Filipino citizen. The alleged subsequent recognition of his natural-born status by the Bureau of Immigration and the DOJ cannot amend the final decision of the trial court stating that respondent Ong and his mother were naturalized along with his father. The series of events and long string of alleged changes in the nationalities of respondent Ong's ancestors, by various births, marriages and deaths, all entail factual assertions that need to be threshed out in proper judicial proceedings so as to correct the existing records on his birth and citizenship. The chain of evidence would have to show that Dy Guiok Santos, respondent Ong's mother, was a Filipino citizen, contrary to what still appears in the records of this Court. Respondent Ong has the burden of proving in court his alleged ancestral tree as well as his citizenship under the time-line of three Constitutions. Until this is done, respondent Ong cannot accept an appointment to this Court as that would be a violation of the Constitution. For this reason, he can be prevented by injunction from doing so.

VALLES VS. COMELEC FACTS: Respondent was born in Australia to a Filipino father and an Australian mother. Australia follows jus soli. She ran for governor. Opponent filed petition to disqualify her on the ground of dual citizenship. HELD: Dual citizenship as a disqualification refers to citizens with dual allegiance. The fact that she has dual citizenship does not automatically disqualify her from running for public office. Filing a certificate of candidacy suffices to renounce foreign citizenship because in the certificate, the candidate declares himself to be a Filipino citizen and that he will support the Philippine Constitution. Such declaration operates as an effective renunciation of foreign citizenship.

BURCA VS. REPUBLIC Facts: Zita Ngo was married to Florencio Burca, a Filipino citizen and a resident of Ormoc City. Prior to her marriage, Zita was a Chinese citizen. The record showed, however, that she was born in Gigaquit, Surigao, and was a holder of Native Born Certificate of Residence No. 46333. She filed a petition declaring herself as possessing all the qualifications and none of the disqualifications for naturalization under Commonwealth Act No. 473, and sought the cancellation of her alien certification of registration with the Bureau of Immigration. The Solicitor General opposed such petition and moved that the petition be dismissed because: (1) there was no procedure under the law that can judicially declare citizenship to a particular person; and (2) fatal defects in the petition. After trial, Zita was declared a Filipino citizen, primarily because she was married to a Filipino citizen. Held: The Supreme Court reversed the ruling of the lower court and held that Zita was not a citizen of the Philippines. It had the same ratiocination as those of its previous rulings, i.e. that the Philippine citizenship of the husband does not ipso facto grant Philippine citizenship to the alien wife. Indeed, the political privilege of citizenship should not be handed out blindly to any alien woman on the sole basis of her marriage to a Filipino irrespective of moral character, ideological beliefs, and identification with Filipino ideals, customs and traditions. [Emphasis supplied.] Thus, if an alien wife of a Filipino wishes to acquire Philippine citizenship, the Supreme Court held that she herself must file a petition for citizenship or naturalization. 1 Citizenship derived from that of another, as from a person who holds citizenship by virtue of naturalization. 2 If there is no valid repatriation, then he can be summarily deported for being an undocumented alien.

BENGZON III VS. HRET Facts: Respondent Teodoro Cruz was a natural-born citizen of the Philippines. He was born in San Clemente, Tarlac, on April 27, 1960, of Filipino parents. The fundamental law then applicable was the 1935 Constitution. On November 5, 1985, however, respondent Cruz enlisted in the United States Marine Corps and without the consent of the Republic of the Philippines, took an oath of allegiance to the United States. As a Consequence, he lost his Filipino citizenship for under Commonwealth Act No. 63, section 1(4), a Filipino citizen may lose his citizenship by, among other, "rendering service to or accepting commission in the armed forces of a foreign country. He was naturalized in US in 1990. On March 17, 1994, respondent Cruz reacquired his Philippine citizenship through repatriation under Republic Act No. 2630. He ran for and was elected as the Representative of the Second District of Pangasinan in the May 11, 1998 elections. He won over petitioner Antonio Bengson III, who was then running for reelection.

Issue: Whether or Not respondent Cruz is a natural born citizen of the Philippines in view of the constitutional requirement that "no person shall be a Member of the House of Representative unless he is a natural-born citizen.

Held: Respondent is a natural born citizen of the Philippines. As distinguished from the lengthy process of naturalization, repatriation simply consists of the taking of an oath of allegiance to the Republic of the Philippine and registering said oath in the Local Civil Registry of the place where the person concerned resides or last resided. This means that a naturalized Filipino who lost his citizenship will be restored to his prior status as a naturalized Filipino citizen. On the other hand, if he was originally a natural-born citizen before he lost his Philippine citizenship, he will be restored to his former status as a natural-born Filipino.

RE: APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION TO THE PHILIPPINE BAR. VICENTE D CHING FACTS: Petitioner, who resided in the Philippines since his birth during the 1935 Constitution, is a legitimate son of a Filipina married to a Chinese citizen. Subsequently, petitioner elected Philippine citizenship 14 years after he reached the age of majority. OSG recommends the relaxation of the standing rule on the construction of the phrase reasonable period and the allowance of the petitioner to elect Philippine citizenship due to circumstances like petitioner having lived in the Philippines all his life and his consistent belief that he is a Filipino. ISSUE: Whether or not a legitimate child under the 1935 Constitution of a Filipino mother and an alien father validly elect Philippine citizenship 14 years after he has reached the age of majority. HELD: No, despite the special circumstances, Petitioner failed to validly elect Philippine citizenship. The span of 14 years that lapsed from the time he reached the age of majority until he finally expressed his intention to elect Philippine citizenship is clearly way beyond the contemplation of the requirement upon reaching the age of majority. In addition, there was no reason why he delayed his election of Philippine citizenship.

DJUMANTAN VS. DOMINGO Facts: Bernard Banez, the husband of Marina Cabael, went to Indonesia as a contract worker. On April 3, 1974, he embraced and was converted to Islam. On May 17, 1974, he married petitioner in accordance with Islamic rites. He returned to the Philippines in January 1979. On January 13, 1979, petitioner and her two children with Banez, arrived in Manila as the "guests" of Banez. The latter made it appear that he was just a friend of the family of petitioner and was merely repaying the hospitability extended to him during his stay in Indonesia. When petitioner and her two children arrived at the Ninoy Aquino International Airport on January 13, 1979, Banez, together with Marina Cabael, met them.As "guests," petitioner and her two children lived in the house of Banez. Petitioner and her children were admitted to the Philippines as temporary visitors under Section 9(a) of the Immigration Act of 1940. In 1981, Marina Cabael discovered the true relationship of her husband and petitioner. On March 25, 1982, the immigration status of petitioner was changed from temporary visitor to that of permanent resident under Section 13(a) of the same law. On April 14, 1982, petitioner was issued an alien certificate of registration. Not accepting the set-back, Banez' eldest son, Leonardo, filed a letter complaint with the Ombudsman, who subsequently referred the letter to the CID. On the basis of the said letter, petitioner was detained at the CID detention cell. The CID issued an order revoking the status of permanent resident given to petitioner, the Board found the 2nd marriage irregular and not in accordance with the laws of the Phils. There was thus no basis for giving her the status of permanent residence, since she was an Indonesian citizen and her marriage with a Filipino Citizen was not valid. Thus this petition for certiorari Issue: Whether or not the courts may review deportation proceedings Held : Yes. Section 1 of Article 8 says Judicial Power includes 1) settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable 2) determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the government.

We need not resolve the validity of petitioner's marriage to Banez, if under the law the CID can validly deport petitioner as an "undesirable alien" regardless of her marriage to a Filipino citizen. Generally, the right of the President to expel or deport aliens whose presence is deemed inimical to the public interest is as absolute and unqualified as the right to prohibit and prevent their entry into the country. However, under clause 1 of Section 37(a) of the Immigration Act of 1940 an "alien who enters the Philippines after the effective date of this Act by means of false and misleading statements or without inspection and admission by the immigration authorities at a designated port of entry or at any place other than at a designated port of entry" is subject to deportation. The deportation of an alien under said clause of Section 37(a) has a prescriptive period and "shall not be effected ... unless the arrest in the deportation proceedings is made within five years after the cause for deportation arises". Tolling the prescriptive period from November 19, 1980, when Leonardo C. Banez informed the CID of the illegal entry of petitioner into the country, more than five years had elapsed before the issuance of the order of her deportation on September 27, 1990.

MERCADO VS. MANZANO

Facts: Petitioner Ernesto Mercado and Private respondent Eduardo Manzano are candidates for the position of Vice-Mayor of Makati City in the May, 1998 elections. Private respondent was the winner of the said election but the proclamation was suspended due to the petition of Ernesto Mamaril regarding the citizenship of private respondent. Mamaril alleged that the private respondent is not a citizen of the Philippines but of the United States. COMELEC granted the petition and disqualified the private respondent for being a dual citizen, pursuant to the Local Government code that provides that persons who possess dual citizenship are disqualified from running any public position. Private respondent filed a motion for reconsideration which remained pending until after election. Petitioner sought to intervene in the case for disqualification. COMELEC reversed the decision and declared private respondent qualified to run for the position. Pursuant to the ruling of the COMELEC, the board of canvassers proclaimed private respondent as vice mayor. This petition sought the reversal of the resolution of the COMELEC and to declare the private respondent disqualified to hold the office of the vice mayor of Makati.

Issue: Whether or Not private respondent is qualified to hold office as Vice-Mayor.

Held: Dual citizenship is different from dual allegiance. The former arises when, as a result of the concurrent application of the different laws of two or more states, a person is simultaneously considered a national by the said states. For instance, such a situation may arise when a person whose parents are citizens of a state which adheres to the principle of jus sanguinis is born in a state which follows the doctrine of jus soli. Private respondent is considered as a dual citizen because he is born of Filipino parents but was born in San Francisco, USA. Such a person, ipso facto and without any voluntary act on his part, is concurrently considered a citizen of both states. Considering the citizenship clause (Art. IV) of our Constitution, it is possible for the following classes of citizens of the Philippines to posses dual citizenship: (1) Those born of Filipino fathers and/or mothers in foreign countries which follow the principle of jus soli; (2) Those born in the Philippines of Filipino mothers and alien fathers if by the laws of their fathers country such children are citizens of that country; (3) Those who marry aliens if by the laws of the latters country the former are considered citizens, unless by their act or omission they are deemed to have renounced Philippine citizenship. Dual allegiance, on the other hand, refers to the situation in which a person

simultaneously owes, by some positive act, loyalty to two or more states. While dual citizenship is involuntary, dual allegiance is the result of an individuals volition. By filing a certificate of candidacy when he ran for his present post, private respondent elected Philippine citizenship and in effect renounced his American citizenship. The filing of such certificate of candidacy sufficed to renounce his American citizenship, effectively removing any disqualification he might have as a dual citizen. By declaring in his certificate of candidacy that he is a Filipino citizen; that he is not a permanent resident or immigrant of another country; that he will defend and support the Constitution of the Philippines and bear true faith and allegiance thereto and that he does so without mental reservation, private respondent has, as far as the laws of this country are concerned, effectively repudiated his American citizenship and anything which he may have said before as a dual citizen. On the other hand, private respondents oath of allegiance to the Philippine, when considered with the fact that he has spent his youth and adulthood, received his education, practiced his profession as an artist, and taken part in past elections in this country, leaves no doubt of his election of Philippine citizenship.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Relationship Between International Law & Municipal LawDocument8 pagesRelationship Between International Law & Municipal LawWatch ManNo ratings yet

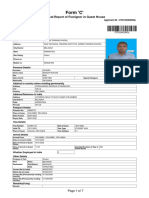

- Form 'C': Arrival Report of Foreigner in Guest HouseDocument7 pagesForm 'C': Arrival Report of Foreigner in Guest HouseGursimranjeet SinghNo ratings yet

- U.S. Expatriation Act of 1907Document8 pagesU.S. Expatriation Act of 1907tulsatops2100% (1)

- Philippines VS China Case SummaryDocument111 pagesPhilippines VS China Case SummaryRubenNo ratings yet

- Bar 1990-1992Document14 pagesBar 1990-1992juju_batugalNo ratings yet

- Philippine Passport Application Form 2015Document1 pagePhilippine Passport Application Form 2015japopalattaoNo ratings yet

- Case Concerning Delimitation of The Maritime Boundary in The Gulf of Maine Area Judgment of 12 October 1984Document7 pagesCase Concerning Delimitation of The Maritime Boundary in The Gulf of Maine Area Judgment of 12 October 1984Ge LatoNo ratings yet

- 42 Del Socorro vs. Wilsem - DigestDocument1 page42 Del Socorro vs. Wilsem - DigestRexNo ratings yet

- Villegas Anjiolini PUBLICINTERNATIONALLAWDocument3 pagesVillegas Anjiolini PUBLICINTERNATIONALLAWVanzNo ratings yet

- North Sea Continental Shelf Cases Germany v. Denmark - HollandDocument2 pagesNorth Sea Continental Shelf Cases Germany v. Denmark - HollandSecret SecretNo ratings yet

- Visa Application Form South IndiaDocument1 pageVisa Application Form South Indiabindu mathaiNo ratings yet

- IcjDocument18 pagesIcjakshay kharteNo ratings yet

- UN1950Document19 pagesUN1950Rosa LuxemburgNo ratings yet

- Aid To The Authorities of A StateDocument20 pagesAid To The Authorities of A StateAbdisamed AllaaleNo ratings yet

- What Is Refugee Law?: Sandeep ChawdaDocument10 pagesWhat Is Refugee Law?: Sandeep ChawdaSandeep ChawdaNo ratings yet

- 1500+ Research TopicsDocument47 pages1500+ Research TopicsrishikNo ratings yet

- Legal Consequences of The Construction of A Wall in The Occupied Palestinian TerritoryDocument2 pagesLegal Consequences of The Construction of A Wall in The Occupied Palestinian TerritoryElaiza Jamez PucateNo ratings yet

- Ajil - Infovil - 111. Ajl - Inf - 8989867544456Document260 pagesAjil - Infovil - 111. Ajl - Inf - 8989867544456RamazanNo ratings yet

- Urbaser V Argentine RepublicDocument30 pagesUrbaser V Argentine RepublicShirat MohsinNo ratings yet

- Alfredvonengelf 001Document39 pagesAlfredvonengelf 001Jelena Blagojevic-IgnjatovicNo ratings yet

- Public International Law Laws of The SeaDocument32 pagesPublic International Law Laws of The SeakuheDSNo ratings yet

- Part 4 Pil Midterm NotesDocument15 pagesPart 4 Pil Midterm NotesRubenNo ratings yet

- MOY YA LIM YAO vs. COMMISSIONER OF IMMIGRATION, 41 SCRA 292 (1971)Document1 pageMOY YA LIM YAO vs. COMMISSIONER OF IMMIGRATION, 41 SCRA 292 (1971)Joy DLNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Support and Guarantee: (Visit of A Family Relative)Document1 pageAffidavit of Support and Guarantee: (Visit of A Family Relative)Jovel V. MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Australia Resident Return Visa RequirementsDocument4 pagesAustralia Resident Return Visa RequirementsFadlyNo ratings yet

- Fullmakt en 107011Document1 pageFullmakt en 107011Yacine MoustaphaNo ratings yet

- Sahil PassportDocument2 pagesSahil PassportAbhay AnantNo ratings yet

- Speech DefenceDocument7 pagesSpeech DefenceAnuj ShahNo ratings yet

- Towards A Single Definition of Armed Conflict in IHL - JAMES G STEWARTDocument38 pagesTowards A Single Definition of Armed Conflict in IHL - JAMES G STEWARTchitru_chichruNo ratings yet

- Daniel - CBP OneDocument3 pagesDaniel - CBP OneCIBER JUCH JUCHITANNo ratings yet