Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Miranda's Paradox Essay Oefeningen

Uploaded by

Patricio PérezOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Miranda's Paradox Essay Oefeningen

Uploaded by

Patricio PérezCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Spring 2012 Patricio Prez Dr. Yuri Cowan

Mirandas Paradox: Agency and visibility in The Tempest

(Postcolonial) Revisionist readings of Shakespeares The Tempest since the 1960s have focused extensively on the role of Caliban as a symbol of resistance and rebellion in colonial regimes but have paid considerably less attention to the figure of Miranda both as subject of a patriarchal regime and as complicit to her fathers colonial subjugation of the native inhabitant of the island, Caliban. I intend to draw attention on her paradoxical position of oppressed and oppressor on the one hand, and to contribute to a literacy of Miranda that maps visibility of minorities in social studies, and in society in general, on the other. I will argue in this short essay that while neglecting Mirandas role(s) has been interpreted as a way of reinforcing her marginalised position in the play, putting her on the foreground implies the paradox of recognising her as an active agent playing a questionable role in the exploitation of the island and the enslavement of Caliban. I will also try to demonstrate the ways in which patriarchal and colonialist discourse intersect, a link that has not always been acknowledged by early postcolonial readings that have failed to address the relationship between struggles for territorial and cultural independence and the emancipation of women as Jyotsna Singhs points out, for instance, in relation with rewritings of The Tempest by anti-colonial non-Western authors in the wake of decolonisation (209).

While early (18th and 19th century) romantic readings of The Tempest have seen in Miranda (if shes been seen at all, that is) a symbol of virgin nature or pliant womanliness,

as Jessica Slights argues (360), postcolonial approaches to the play have excluded her on the same scale from her role as a dynamic participant in the plot by focusing on the enslavement of Caliban (Slights 361). Feminist readings of The Tempest on the other hand have denounced this exclusion of Miranda from critical discourses and have this way contributed to a visibility of her character but they have more often than not neglected Mirandas necessary complicity in the colonial subjugation of the island and its native inhabitant, Caliban. In Jyotsna Singhs landmark essay Caliban versus Miranda, Miranda is understood as a symbolic gift in a system of women-gift exchange amongst men in which she plays a completely passive role being alternatively disputed, offered, denied and taken by the male characters of Prospero, Caliban and Ferdinand (211). Singh argues that the basis of the power struggle between Prospero and Caliban () is an implicit consensus about the role of woman as a gift to be exchanged (215). Essentially, Miranda is denied all agency being objectified in the power transactions of an all-male community. She represents the means through which Prospero will get them into the royal court of Naples which he therefore needs to preserve from Caliban who sees in Miranda an object of sexual desire and a means to people the island with his descendants. This objectification nevertheless appears to be only applicable to her role in the context of the negotiations between the three men but doesnt account for the complexity of Mirandas relationship to each of them separately. This is especially true with regard to her relationship with Caliban which reveals a more complex interchange between the two characters. Lorrie J. Leininger, for instance, explores this relationship proposing an alliance between Miranda and Caliban against the omnipotent figure of Prospero (291). And although there is no actual evidence in the text to support this interpretation, it is interesting because it throws light on the intersection of the critical discourses of anti-colonialism and feminism and their common strategies and portrays

Miranda and Caliban as implicit allies in the interconnected struggles for gender and territorial and cultural emancipation. However, their relationship is far from being one of kinship and while they could be, theyre not allies against the patriarchs all-embracing power but rather represent counterpoints in the power structure of the island: Caliban actively plots against Prospero and defies his authority whereas Miranda aligns with her father whose discourse she makes her own; they speak the same language after all for which Caliban curses Prospero, for having it taught to him. She has internalized the colonialist discourse in which Caliban is represented as naturally vile (a villain in Mirandas own words, whom shed rather not even look at) projecting not just the superiority of the colonizers but also the need for the occupation and economic exploitation of the island and the implantation of foreign systems of moral values symbolically conveyed by language in the play. It is here, in my opinion, that Mirandas active role in the political universe of the island is materialized and not, as Jessica Slights claims, in her pity for the victims of the shipwreck or her decision to marry Ferdinand (376). In fact, despite her praiseworthy attempt to emphasize Mirandas agency as a dynamic participant in the fictional world of the play, she fails to give a convincing argument for Mirandas defiance of her fathers authoritarian power, at once exaggerating the extent and significance of her expressions of disagreement (seeing a politically subversive potential (Slights 367) in Mirandas rather nave oversight of her fathers command not to speak to Ferdinand But I prattle/Something too wildly, and my fathers precepts/I therein do forget, for instance) and interpreting her curiosity about her fathers account of the events that led them to the island (Wherefore did they not/That hour destroy us? (I.ii. 138-9)) as a subtle form of challenge to Prosperos authority (368). This inconsistent attempt seems to overlook the fact that even when Miranda disagrees, she is in fact fulfilling her fathers plans

to restore their honour and noble lineage through her royal marriage with the son of the king of Naples.

To sum up, I have argued that recognising Mirandas agency in the fictional (political) world of the island implies the paradox of positioning her as complicit to her fathers colonialist economic and cultural exploitation of the island they inhabit and the enslavement of Caliban, that is a dynamic participant of the power struggle between her and her father on one side, and Caliban on the other. Unlike Slights claim, I suggest that Mirandas role in the play doesnt offer (any) alternative to the paternalist order with which the play opens (376) neither on a discursive level nor in her actions. On the contrary, Miranda identifies herself with her fathers discourse and willingly participates in the patriarchal plan Prospero has designed for her.

Works cited Leininger, Lorie Jerrell, The Miranda Trap: Sexism and Racism in Shakespeare's Tempest in (eds.) Carolyn Ruth Swift Lenz, Gayle Greene, and Carol Thomas Neely, The Woman's Part: Feminist Criticism of Shakespeare, Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1980, pp. 285-94 Shakespeare, William The Tempest (1610-1611), New York: Signet Classic/Penguin edition, 1987 Singh, Jyotsna G. Caliban versus Miranda: Race and Gender Conflicts in Postcolonial Rewritings of The Tempest in (eds.) Valerie Traub, M. Lindsay Kaplan, and Dympna Callaghan, Feminist Readings of Early Modern Culture: Emerging Subjects, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1996, pp. 191-209.

Slights, Jessica, Rape and the Romanticization of Shakespeare's Miranda in Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 41, No. 2, Tudor and Stuart Drama. Houston: Rice University, 2001, pp. 357-379

You might also like

- The Tempest The Theme of Power in The TempestDocument4 pagesThe Tempest The Theme of Power in The TempestSharmila DasNo ratings yet

- Women in ShakespeareDocument12 pagesWomen in Shakespeareryan_hawkins5876No ratings yet

- Makedonski Written TaskDocument4 pagesMakedonski Written TaskMert AjvazNo ratings yet

- (251 5) RPTitusAndronicusDocument3 pages(251 5) RPTitusAndronicusNachtFuehrerNo ratings yet

- Dark Geography of Ninotchka Rosca's 'Bitter Country' StoriesDocument2 pagesDark Geography of Ninotchka Rosca's 'Bitter Country' StoriesDwight AlipioNo ratings yet

- Stories PDFDocument14 pagesStories PDFMaria PaulaNo ratings yet

- Caliban and Post Colonialism in ShakespeareDocument5 pagesCaliban and Post Colonialism in ShakespeareCraptacularNo ratings yet

- The Tempest Gender IssueDocument2 pagesThe Tempest Gender IssueVijay GoplaniNo ratings yet

- Beyond Caliban's Curses: The Decolonial Feminist Literacy of Sycorax by Irene LaraDocument19 pagesBeyond Caliban's Curses: The Decolonial Feminist Literacy of Sycorax by Irene Laracaz__No ratings yet

- The Duchess of Malfi: A Woman's Struggle Against 17th Century PatriarchyDocument8 pagesThe Duchess of Malfi: A Woman's Struggle Against 17th Century PatriarchyJaya PradhanNo ratings yet

- Salman Rushdie's FuryDocument10 pagesSalman Rushdie's FuryadinapoeNo ratings yet

- Essay On ImperialismDocument3 pagesEssay On Imperialismzobvbccaf100% (2)

- Richard III and LKR Exemplar EssayDocument2 pagesRichard III and LKR Exemplar EssaypiethepkerNo ratings yet

- Kindred PresentationDocument20 pagesKindred Presentationapi-252344608100% (1)

- Jeanée P. Sacken, "George Sand, Kate Chopin, Margaret Atwood, and The Redefinition of Self"Document6 pagesJeanée P. Sacken, "George Sand, Kate Chopin, Margaret Atwood, and The Redefinition of Self"PACNo ratings yet

- María Clara's Enduring Legacy as a Contested SymbolDocument44 pagesMaría Clara's Enduring Legacy as a Contested SymbolJeremiah Ciarra D. FloresNo ratings yet

- C 2007seap - Indo.1178561789Document4 pagesC 2007seap - Indo.1178561789akhiniezNo ratings yet

- Blood WeddingDocument26 pagesBlood Weddinggarima567No ratings yet

- Rabindra Bharati University: UG3 SemesterDocument5 pagesRabindra Bharati University: UG3 SemesterTiyas MondalNo ratings yet

- Deflection of Personal Integrity in Mario Vargas Llosa's Conversation in The Cathedral and William Faulkner's The Sound and The FuryDocument4 pagesDeflection of Personal Integrity in Mario Vargas Llosa's Conversation in The Cathedral and William Faulkner's The Sound and The FurybathadNo ratings yet

- The Tempest Revision PowerpointDocument17 pagesThe Tempest Revision Powerpointapi-288973454No ratings yet

- Questions On The TempestDocument3 pagesQuestions On The TempestCamila Franco BatistaNo ratings yet

- "Masculinities in Two Novelized YA 'Cinderella' Adaptations: Disrupting Hegemonic Power and Relationship" (Linda T Parsons)Document17 pages"Masculinities in Two Novelized YA 'Cinderella' Adaptations: Disrupting Hegemonic Power and Relationship" (Linda T Parsons)Boey RyanNo ratings yet

- PATRONAGE AND PORNOGRAPHY PPT ReportDocument17 pagesPATRONAGE AND PORNOGRAPHY PPT Reportaleck dacuycuyNo ratings yet

- Signifying Circe by Judith Fletcher PDFDocument15 pagesSignifying Circe by Judith Fletcher PDFsammiedearbornNo ratings yet

- Reproducing Time, Reproducing History: Love and Black Feminist Sentimentality in Octavia Butler's KindredDocument19 pagesReproducing Time, Reproducing History: Love and Black Feminist Sentimentality in Octavia Butler's Kindredeverblessed ajieNo ratings yet

- González On RamírezDocument10 pagesGonzález On RamírezBryce BarkerNo ratings yet

- EDUC3013 Essay 2Document7 pagesEDUC3013 Essay 2Zoie SuttonNo ratings yet

- The Rover as a Feminist Play: How Women Characters Assert AgencyDocument18 pagesThe Rover as a Feminist Play: How Women Characters Assert AgencyRitanwita DasguptaNo ratings yet

- Short Note On Samuel RichardsonDocument1 pageShort Note On Samuel RichardsonManish Kumar Dubey0% (1)

- Prospero and Paternal PowerDocument6 pagesProspero and Paternal PowerMorten Oddvik100% (4)

- Desert Pandemonium - Cormac McCarthy's Apocalyptic Western in Blood MeridianDocument18 pagesDesert Pandemonium - Cormac McCarthy's Apocalyptic Western in Blood MeridianMichael AnnangNo ratings yet

- Paper 104Document6 pagesPaper 104Puja DasNo ratings yet

- Cowboys and SailorsDocument8 pagesCowboys and Sailorsapi-271748556No ratings yet

- Tempest Act 3 AnalysisDocument3 pagesTempest Act 3 AnalysisSajin Santhosh100% (1)

- Tragic Tale of a Woman's Struggle Against PatriarchyDocument7 pagesTragic Tale of a Woman's Struggle Against PatriarchyBinasree GhoshNo ratings yet

- Iron WeedDocument15 pagesIron WeedJim BeggsNo ratings yet

- The Last Shades of Scarlet: Wolves of LaconiaFrom EverandThe Last Shades of Scarlet: Wolves of LaconiaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood: Why You'll Like It: About The AuthorDocument2 pagesThe Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood: Why You'll Like It: About The AuthorCode Breaker 03: Youki Tenpouin (The Legend)No ratings yet

- Marxist Criticismthe Feminist Approachpsychoanalysis: Ways of Thinking About King LearDocument1 pageMarxist Criticismthe Feminist Approachpsychoanalysis: Ways of Thinking About King LearJoy Prokash RoyNo ratings yet

- The Fortunes of Polly Mahony Henry Handel Richardson'S Woman in A Man'S WorldDocument13 pagesThe Fortunes of Polly Mahony Henry Handel Richardson'S Woman in A Man'S WorldmrkennygoitaNo ratings yet

- Lysistrata From A Non Feminist PerspectiveDocument9 pagesLysistrata From A Non Feminist PerspectiveIsaac CarranzaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary American Fiction Essay FinalDocument14 pagesContemporary American Fiction Essay FinalJoan SerraNo ratings yet

- Post Colonial Response To The TempestDocument2 pagesPost Colonial Response To The TempestMelNo ratings yet

- Assignment Point of ViewDocument9 pagesAssignment Point of ViewRashmi MehraNo ratings yet

- American and English Earth: A Review of Kay Boyle and William Faulkner NovelsDocument6 pagesAmerican and English Earth: A Review of Kay Boyle and William Faulkner NovelsMauricio D. Aguilera LindeNo ratings yet

- Eroticism in The Cold Climate of Northern Ireland in Christina Reid's PlayDocument19 pagesEroticism in The Cold Climate of Northern Ireland in Christina Reid's PlayKatarzynaOjrzyńskaNo ratings yet

- AVERIA - KLAUSMENE - Performance Task 1 (Final)Document5 pagesAVERIA - KLAUSMENE - Performance Task 1 (Final)Klausmene AveriaNo ratings yet

- Critique-Sabangan, China May GDocument3 pagesCritique-Sabangan, China May GChina May SabanganNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 5Document29 pages10 - Chapter 5AnithaNo ratings yet

- Tar Baby: Tar Baby (1981) Is Set On An Imaginary Caribbean Island and Involves TheDocument34 pagesTar Baby: Tar Baby (1981) Is Set On An Imaginary Caribbean Island and Involves Thesar0000No ratings yet

- To Kill A Mockingbird and Persepolis Comparitive EssayDocument5 pagesTo Kill A Mockingbird and Persepolis Comparitive EssayMonica SullivanNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Gender in Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon.Document14 pagesThe Politics of Gender in Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon.He LiNo ratings yet

- Historical ApproachDocument63 pagesHistorical ApproachMarta GortNo ratings yet

- One Last Time PDFDocument14 pagesOne Last Time PDFsuperultimateamazingNo ratings yet

- In The Cathedral ShortDocument11 pagesIn The Cathedral ShortGraciela RuizNo ratings yet

- 482 521 1 PBDocument9 pages482 521 1 PBTariq MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Universidad de Sevilla: "The Way You Wear Your Hat": Performativity and Self-Invention in Jackie Kay'sDocument10 pagesUniversidad de Sevilla: "The Way You Wear Your Hat": Performativity and Self-Invention in Jackie Kay'sJuan Angel CiarloNo ratings yet

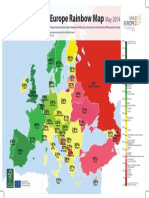

- Side B - Rainbow Europe Index May 2014Document1 pageSide B - Rainbow Europe Index May 2014Patricio PérezNo ratings yet

- Side A - Rainbow Europe Map May 2014Document1 pageSide A - Rainbow Europe Map May 2014Patricio PérezNo ratings yet

- The Wounded Body of Proletarian Homosexuality in Pedro Lemebel's Loco Afán - Palaversich, Diana & Allatson, PaulDocument21 pagesThe Wounded Body of Proletarian Homosexuality in Pedro Lemebel's Loco Afán - Palaversich, Diana & Allatson, PaulPatricio PérezNo ratings yet

- Pountain 2003 - 9.2. Vestigial Spanish VarietiesDocument24 pagesPountain 2003 - 9.2. Vestigial Spanish VarietiesPatricio PérezNo ratings yet

- Argentine Intellectuals and HomoeroticismDocument11 pagesArgentine Intellectuals and HomoeroticismPatricio PérezNo ratings yet

- 3 DDuckDocument6 pages3 DDucksr_mahapatraNo ratings yet

- Polish RecipesDocument20 pagesPolish RecipesPatricio Pérez100% (2)

- The Damnation of FaustusDocument12 pagesThe Damnation of FaustusPatricio PérezNo ratings yet

- Urology Doc CircumcisionDocument7 pagesUrology Doc Circumcisionsekhmet77100% (2)

- Images of Women in Namitha Gokhale's WorksDocument5 pagesImages of Women in Namitha Gokhale's WorksEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Marmoset ComplaintDocument23 pagesMarmoset ComplaintKenan FarrellNo ratings yet

- Urdu Adab Dehli Shamim Hanfi Number October 2017 Mar 2018Document270 pagesUrdu Adab Dehli Shamim Hanfi Number October 2017 Mar 2018Rashid Ashraf100% (1)

- Make a 3D Text in GimpDocument19 pagesMake a 3D Text in GimpAlyssa Jed TenorioNo ratings yet

- Calypso GenreDocument14 pagesCalypso GenreLucky EluemeNo ratings yet

- Quiz on English grammar and verb tenses under 40 charsDocument4 pagesQuiz on English grammar and verb tenses under 40 charsKaren Chinga yesquenNo ratings yet

- A Million Dreams-SongDocument2 pagesA Million Dreams-SongMaram Mostafa MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Brain Pickings - An Inventory of The Meaningful LifeDocument16 pagesBrain Pickings - An Inventory of The Meaningful Lifegladis rosacia100% (1)

- Knapp (1989), Finale of Brahms 4Document16 pagesKnapp (1989), Finale of Brahms 4밤하늘No ratings yet

- Charles Grandison FinneyDocument5 pagesCharles Grandison FinneyAnonymous vcdqCTtS9No ratings yet

- Penilaian Akhir Semester (Pas) TAHUN PELAJARAN 2018/2019Document3 pagesPenilaian Akhir Semester (Pas) TAHUN PELAJARAN 2018/2019selviNo ratings yet

- Yarn Splicing Types of Yarn Splices Method of Yarn SplicingDocument6 pagesYarn Splicing Types of Yarn Splices Method of Yarn SplicingMohammed Atiqul Hoque ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Reported Speech ExercisesDocument8 pagesReported Speech ExercisesDenisa TuronyNo ratings yet

- Pachisi History & RulesDocument8 pagesPachisi History & RulesMallee Blue Media100% (3)

- Light Travels in A Straight LineDocument3 pagesLight Travels in A Straight LinePeter ChaiNo ratings yet

- History of Anglo-SaxonsDocument13 pagesHistory of Anglo-SaxonsShayne Penn PerdidoNo ratings yet

- Collage CityDocument10 pagesCollage CityJaneeva 95No ratings yet

- Alina Bokovikova CVDocument6 pagesAlina Bokovikova CVapi-293798641No ratings yet

- Present Simple and Past Simple Tenses in EnglishDocument1 pagePresent Simple and Past Simple Tenses in EnglishAnonymous SLYi8ORABNo ratings yet

- From Vertices To Fragments: Rasterization: Frame BufferDocument22 pagesFrom Vertices To Fragments: Rasterization: Frame BufferPallavi PatilNo ratings yet

- Non-Aqueous Titrations & Complexometric TitrationsDocument8 pagesNon-Aqueous Titrations & Complexometric TitrationsAmit GautamNo ratings yet

- (Jim Surmanek) Introduction To Advertising Media (BookFi) PDFDocument393 pages(Jim Surmanek) Introduction To Advertising Media (BookFi) PDFIoana-Nely MilitaruNo ratings yet

- Ernst Cassirer's Metaphysics of Symbolic Forms, A Philosophical Commentary - Thora Ilin Bayer PDFDocument221 pagesErnst Cassirer's Metaphysics of Symbolic Forms, A Philosophical Commentary - Thora Ilin Bayer PDFatila-4-ever100% (4)

- Jencyn Strickland - 1 Tracking ThemesDocument2 pagesJencyn Strickland - 1 Tracking Themesapi-445373825No ratings yet

- Gretsch Pricelist Featured Product Guide 2014Document11 pagesGretsch Pricelist Featured Product Guide 2014EdmarMatosNo ratings yet

- UNAC Exam on Microcontrollers and Embedded SystemsDocument2 pagesUNAC Exam on Microcontrollers and Embedded SystemsBranco Costa OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Gayatri Mantra, Chandi Homam, Dhanvanthri HomamDocument3 pagesBenefits of Gayatri Mantra, Chandi Homam, Dhanvanthri HomamVedic Folks0% (1)

- Towards A Theology of ArtsDocument10 pagesTowards A Theology of ArtsAndréNo ratings yet

- Places to Visit This Summer in the West MidlandsDocument1 pagePlaces to Visit This Summer in the West MidlandsNacely Ovando CuadraNo ratings yet