Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Using Health Observances To Promote Wellness in Community Pharmacies

Uploaded by

ladeda14Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Using Health Observances To Promote Wellness in Community Pharmacies

Uploaded by

ladeda14Copyright:

Available Formats

COMMENTARY

Using Health Observances to Promote Wellness in Community Pharmacies

Lynne Marie Ciardulli and Jean-Venable R. Goode

Objectives: To provide pharmacists in community practice a framework for using national health observances as opportunities to promote patients health through education and screenings, to discuss obstacles pharmacists may encounter when developing services within their pharmacies, and to outline examples of activities pharmacists can perform for specific health observances. Data Sources: Articles published between January 1970 and April 2002 were identified through MEDLINE using the search terms wellness, disease

prevention, health promotion, Healthy People 2010, treatment of high cholesterol, treatment of high blood pressure, and levels of participation. Additional articles were identified from Web sites and reports from the federal Office of Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion (ODPHP), American Heart Association, American Diabetes Association, National Osteoporosis Foundation, National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Consumer Product Safety Commission, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Synthesis: Healthy People 2010 is a federal program with the goal of increasing the quality and years of healthy life and eliminating health disparities among populations. ODPHP publishes a list of national health observances each year. Community pharmacists can use these month- and week-long observances as opportunities to work toward achieving Healthy People 2010 goals by advocating, facilitating, and/or providing education and screenings to their patients. This article presents advice for pharmacists who want to develop pharmacy-based health promotion activities at various levels of resources and commitment. Specific suggestions include tips on preparing for and implementing education and screening programs and overcoming potential obstacles. Conclusion: As the most accessible health care professionals, pharmacists are in a unique position to help the nation achieve the goals of Healthy People 2010 through their involvement in the promotion of wellness.

Keywords: Health observances, wellness, community pharmacy, disease prevention, Healthy People 2010. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43:618.

The two main goals of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2010 initiative are to increase the quality and years of healthy life and eliminate health disparities among various subgroups of the American populace.1 Public health professionals, including pharmacists, have responsibilities to educate the community on disease control and health promotion and to work toward meeting the goals detailed in Healthy People

Received May 9, 2002, and in revised form September 5, 2002. Accepted for publication November 7, 2002. Lynne Marie Ciardulli, PharmD, is assistant professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Bernard J. Dunn School of Pharmacy, Shenandoah University, Winchester, Va. Jean-Venable Kelly R. Goode, PharmD, BCPS, is associate professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, School of Pharmacy, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va. At the time this article was written, Ciardulli was community pharmacy practice resident, School of Pharmacy, Virginia Commonwealth University and Ukrops Pharmacy. Correspondence: Jean-Venable R. Goode, PharmD, BCPS, School of Pharmacy, Virginia Commonwealth University, P.O. Box 980533, Richmond, VA 23298-0533. E-mail: jrgoode@vcu.edu. Fax: 804-828-8359. See related articles on pages 13 and 56.

2010: Understanding and Improving Health.1 The major causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States include heart disease, cancer, lung disease, and diabetes. These diseases can be controlled or prevented by educating patients on the importance of risk factor modification and evaluative screenings.1,2 The health and well-being of millions of Americans are affected by common diseases (see Table 1) that may be controlled or prevented by early interventions, such as education and screening.36 Each year, the federal Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion publishes a list of national health observances.7 Community pharmacists can use these month- or week-long occasions as opportunities to work toward achieving Healthy People 2010 goals by advocating, facilitating, and/or providing education and screenings to their patients.

Objectives

Our main objective in this article is to provide pharmacists in

Vol. 43, No. 1

January/February 2003

Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association

61

COMMENTARY

Health Observances

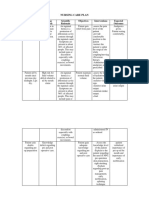

Table 1. Health Impact of Common Diseases

Diseases Cardiovascular diseases 1,3 Health Effects More than 60 million Americans have one or more forms of cardiovascular disease. More than 50 million Americans have high blood pressure, 4.8 million have congestive heart failure, and 4.5 million have had a stroke. Of the Americans who die of cardiovascular disease each year, more than 150,000 are younger than 65 years old. An estimated 11 million people in the United States have been diagnosed with diabetes. A total of 798,000 new cases of type 2 diabetes are diagnosed in the United States each year. Diabetes is a positive risk factor for heart disease. Approximately 102.3 million Americans have total cholesterol levels greater than 200 mg/dL, and 41.3 million Americans have total cholesterol levels greater than 240 mg/dL. Approximately 48.6% of Americans over 20 years old have a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level greater than 130 mg/dL, and 39% have a high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level less than 40 mg/dL. Approximately 1 in 4 adult Americans have high blood pressure (> 140/90 mm Hg). Of those with high blood pressure, 31.6% are unaware of their condition. Hypertension is a positive risk factor for heart disease. The two most common vaccine-preventable diseases together are the sixth leading cause of death among Americans. Pneumonia causes approximately 10,000 to 14,000 avoidable deaths per year. Influenza causes an average of 110,000 hospitalizations and 20,000 avoidable deaths per year. This disease affects more than 10 million Americans. Some 18 million people have low bone mass or osteopenia. Osteoporosis is responsible for 1.5 million fractures annually in America. Both of these cancers have a high survival rate if detected early. In the United States, an estimated 200,000 new cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed in 2001. Approximately 32,000 men die from prostate cancer each year. In women over the age of 40, 88% have had at least one mammogram. In women over the age of 50, only 80% have had a mammogram in the last 2 years. In the United States, an estimated 192,000 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 47,100 cases of in situ breast cancer were discovered in 2001. Approximately 40,200 women die from breast cancer each year.

Diabetes 4

Dyslipidemia 3

Hypertension 3

Influenza and pneumonia1

Osteoporosis 5

Prostate cancer and breast cancer6

community practice a framework for using national health observances as opportunities to promote patients health through education and screenings. Through a detailed, practical, and applied approach, this commentary discusses the procedures for preparing, planning, and implementing wellness services geared toward health promotion. Our second objective is to discuss the obstacles pharmacists may encounter when developing services within their pharmacies and to provide ideas and suggestions for overcoming these obstacles. Our third objective is to outline examples of activities pharmacists can perform for specific national health observances.

Levels of Participation

Pharmacists can participate at three levels of preparing, planning, and implementing health promotion activities (see Table 2).8 Health advocacy is the first level of health promotion. Pharmacists can use a variety of advocacy methods to provide health-related information to patients, including dropping flyers into shopping or prescription bags (bag stuffers), giving more detailed educational pamphlets to patients at the pharmacy counter or during counseling, putting up posters, distributing health assessment quizzes, and showing videos. Also, at the point of dispensing, pharmacists can talk with patients or review the content of written brochures that

address a specific disease or type of drug therapy.8 Facilitation of public health services, often through collaboration with other health care providers, is the next level of possible pharmacist activity in health promotion. As a facilitator, a pharmacist might invite nurses, therapists, and dietitians to the pharmacy to perform blood pressure or cholesterol screenings or teach classes on exercise or diet. Since the pharmacy is often the most accessible and convenient health care location, making screening and wellness services available in the pharmacy can improve patients access to such services.8 Many pharmacists across the country are developing and implementing wellness services, such as education and screenings. These services provide patients with a more cohesive continuum of care, including screening and education at each pharmacy visit. To provide such advanced services, pharmacists must invest some time in acquiring particular skills and obtaining continuing education or certifications.8 Table 3 lists programs offered by professional associations to further the education of pharmacists and other health care professionals in terms of meeting the needs of patients with common diseases. Before implementing pharmaceutical care programs, pharmacists must check their states pharmacy practice laws to find out what activities they are permitted to perform. Participation at all levels of public health involvement is impor-

62

Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association

January/February 2003

Vol. 43, No. 1

Health Observances

COMMENTARY

tant for promoting health and wellness in the community, and Table 2 shows examples of activities that can be performed at each level. It may not be feasible to incorporate each level of participation into all health observances. Pharmacists should assess the needs of the patient population they serve and assess their personal ability and the commitment of the pharmacy owner/managers to support one of the three levels of participation.

Table 2. Three Levels of Health Promotion

Level Advocacy Examples of Possible Pharmacist Activity Distribute brochures and other patient education materials Distribute risk assessment quizzes Demonstrate how to use pharmacy devices and medication delivery devices (e.g., inhalers) Sponsor screenings in the pharmacy Sponsor community health fairs Ask other health professionals to provide services in the pharmacy Provide health screenings Provide disease management services Provide immunizations

Facilitation

Preparing for a Wellness Project

Provision

First, conduct a needs assessment and examine the pharmacys patient population. Needs assessments can be performed by reviewing patient profiles for common diseases, holding focus group discussions with pharmacy customers, and surveying patients. Then identify national health observances that fit the pharmacy patients and communitys demographics. A list of health observances that can be easily promoted in pharmacies is provided in Table 4 and discussed in detail in a later section of this article.7 Next, determine the level of participation that is possible for the pharmacy and staff; this will help in organizing the materials that will be needed for each observance. The choice of level of participation will depend on the pharmacists training and comfort level in providing the service, the time that is available, and management support.

S ource: A dapted fromR eference 8 .

around each targeted health observance. The point person does not have to be a pharmacist. He or she could be a motivated pharmacy technician, a pharmacy student on clerkship rotation, or a community pharmacy resident. In addition, depending on state laws and the rules set forth by management, certain activities might not be feasible. However, remember that advocacy of health and wellness is extremely important and that information can always be made available to patients.

Planning a Wellness Project

The time spent in planning and implementing wellness services will vary depending on the desired level of participation. It may be necessary to enlist the help of one or more members of the pharmacy staff to adequately plan and implement a health observance activity. For whichever level is chosen, develop a timeline for implementation and designate a point person to organize events

Procedures for Advocating W ellness Activities First, collect patient education materials, references, and display materials. Patient education and display materials can be obtained from national organizations that prepare brochures, handouts, posters, and patient risk assessment quizzes on different health topics. For example, the American Heart Association (AHA) has easily downloadable patient education materials on its Web site

Table 3. Professional Association Programs That Address Common Health Needs

Health Topic Diabetes Program (Sponsoring Organization, Web Site) Pharmaceutical Care for Patients with Diabetes (APhA, www.aphanet.org/education/ctp/diabetespat.html) Diabetes Care Certificate Program (NCPA, www.ncpanet.org/nicpo/diabetes.html) Specialty Training Program in Diabetes (American College of Apothecaries, www.acainfo.org/education.htm) Ambulatory Clinical Skills Program: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Management Module (ASHP, www.ashp.org) Certification ProgramCertified Diabetes Educator (American Association of Diabetes Educators, www.aadenet.org) Dyslipidemia Disease State Management ExaminationDyslipidemia (National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, www.nabp.net) Pharmaceutical Care for Patients with Dyslipidemias (APhA, www.aphanet.org/education/ctp/dyslippat.html) Ambulatory Clinical Skills Program: Dyslipidemia Management Module (ASHP, www.ashp.org) Lipid Management Certificate Program (NCPA, www.npcanet.org/nicpo/lipid.html) Immunizations Osteoporosis Pharmacy-Based Immunization Delivery Program (APhA, www.aphanet.org/education/ctp/delivery.html) Immunization Skills Certificate Program (NCPA, www.ncpanet.org/nicpo/immunization.html) Osteoporosis Care Certificate Program (NCPA, www.ncpanet.org/nicpo/osteoporosis.html)

A h = A erican P P A m harm aceutical A ssociation; A H = A erican S S P m ociety of H lth-S stemP ea y harm acists; N P = N C A ational C m nity om u P harm acists A ssociation.

Vol. 43, No. 1

January/February 2003

Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association

63

COMMENTARY

Health Observances

(www.americanheart.org) that can be printed and handed out in the pharmacy. National organizations Web sites are also great places to find reference materials about diseases. Most of these organizations have a special area of their sites set aside for professionals seeking the most recent information about a disease. Another resource for patient educational materials is pharmaceutical industry representatives. It is important, however, to make sure the information is unbiased so that patients will not be misled or confused. Next, prepare pharmacy staff by discussing the activities planned in conjunction with a national health observance. Make sure all employees in the pharmacy know about the plan so that they can share accurate information with patients. Then make sure the staff understands when particular services will be provided and review how to identify and refer patients for each health promotion. Set aside space either on the counter or on a table outside the pharmacy to display patient information materials. Finally, implement the service. The pharmacys point person for the national health observance advocacy activity is responsible for making sure that the collected patient education materials are well

Table 4. Selected Health Observances for 2003

Month January Health Observances (Related Organization W eb Site) National Birth Defects Prevention Month (www.modimes.org) National Glaucoma Awareness Month (www.preventblindness.org) Healthy Weight W eek (www.healthyweight.net) American Heart Month (www.americanheart.org) National Condom Day (www.ashastd.org) Wise Health Consumer Month (www.healthylife.com) National Nutrition Month (www.eatright.org/nnm) National Poison Prevention Week (www.cpsc.gov) American Diabetes Alert (www.diabetes.org) Cancer Control Month (www.cancer.org) National STD Awareness Month (www.ashastd.org) National Public Health W eek (www.apha.org) Kick Butts Day (www.tobaccofreekids.org) World Health Day (www.who.int/world-health-day/eng.shtml) National Infants Immunization W eek (www.cdc.gov/nip) Asthma and Allergy Awareness Month (www.aafa.org) Hepatitis Awareness Month (www.hepfi.org) National Arthritis Month (www.arthritis.org) National High Blood Pressure Education Month (www.nhlbi.nih.gov) National Melanomas/Skin Cancer Detection and Prevention Month (www.aad.org) National Osteoporosis Prevention Month (www.nof.org) National Stroke Awareness Month (www.stroke.org) Food Allergy Awareness Week (www.foodallergy.org) National Senior Health and Fitness Day (www.fitnessday.com) World No Tobacco Day (www.worldnotobaccoday.com)

stocked, displayed appropriately, and always available. Also, a pharmacist must be available to answer questions about the materials and the disease or condition.

Procedures for Facilitating W ellness Activities Of the three levels of involvement in health promotion and wellness activities, facilitation is the simplest. Begin by gathering information and patient education materials, as described in the previous section. Next, contact and schedule local provider groups who offer the services to be promoted. Provider groups might include nurses, dietitians, massage therapists, and exercise therapists who are willing to come to the pharmacy to provide services ranging from cholesterol screenings to educational demonstrations on diet and exercise. Advertising will help to ensure events are successful. Use signs placed throughout the pharmacy, notices on outside marquee boards, oral reminders at the point of dispensing, bag stuffers,

Month June

Health Observances (Related Organization Web Site) Fireworks Safety Month (www.preventblindness.org) National Headache Awareness Week (www.headaches.org) National Mens Health W eek (www.menshealthweek.org) Fireworks Safety Month through July 4 (www.preventblindness.org) W orld Breast-feeding W eek (www.lalecheleague.org) National Immunization Awareness Month (www.partnersforimmunization.org)

February

July August

March

April

September Cold and Flu Campaign (www.lungusa.org) Healthy Aging Month (www.healthyaging.net) National Cholesterol Education Month (www.nhlbi.nih.gov) National Food Safety Education Month (www.nraef.org/ifsc) Prostate Cancer Awareness Month (www.4npcc.org) October National Breast Cancer Awareness Month (www.nbcam.org) Family Health Month (www.familyhealthmonth.org) Healthy Lung Month (www.lungusa.org) Talk About Prescriptions Month (www.talkaboutrx.org) National Adult Immunization Awareness W eek (www.nfid.org/ncai) National Liver Awareness Month (www.liverfoundation.org) National Health Education W eek (www.nche.org) American Diabetes Month (www.diabetes.org) Great American Smokeout (www.cancer.org) GERD Awareness Week (www.iffgd.org) W orld AIDS Day (www.worldaidsday.org) National Hand Washing Awareness W eek (www.henrythehand.com)

May

November

December

64

Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association

January/February 2003

Vol. 43, No. 1

Health Observances

COMMENTARY

notices in local newsletters or periodicals, and advertisements on radio or television. Make sure that the advertised message is being directed to the target audience. For example, advertisements or news articles about a cholesterol screening will have minimal effect if they appear in a community newsletter predominantly read by teenagers. As with advocating wellness activities, a point person should be designated to oversee the planning of a facilitation. This person would be responsible for contacting visiting health care providers, scheduling events, and confirming participation. He or she should ensure that everything is in place for visiting health care providers, including tables, chairs, and electrical access. Local provider groups that come to deliver services may or may not document their outcomes. In either case, the pharmacy should document outcomes using paper forms or computer programs. Documentation tools include liability waivers and patient data result forms. A liability waiver is a statement a patient signs releasing all of the involved parties from liability should injury occur and giving a provider permission to perform a service. A data result form allows a provider to record a patients results from a screening. This form is provided to the patient for his or her personal records. Signed liability waivers and copies of patient results should be stored in the pharmacy. In addition, progress notes could be initiated for each patient to aid the pharmacist in providing a continuum of care to patients who have repeat visits.

Procedures for Providing W ellness Activities Again, begin by gathering information and patient education materials. If the service will involve pharmacists and/or laboratory technologists performing fingersticks, then the pharmacy must follow the rules and regulations of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). CLIA was passed by Congress in 1988 to help ensure that patients lab test results are accurate, reliable, and timely regardless of where they are performed. The law defines a laboratory as any facility which performs laboratory testing on specimens derived from humans for the purpose of providing information for the diagnosis, prevention, treatment of disease, or impairment of, or assessment of health. CLIA regulations have established three categories of tests: waived complexity, moderate complexity, and high complexity. Tests performed at pharmacies generally fall into the waived complexity category. For more information on how to achieve CLIA recognition and view a list of waived tests, visit http://cms. hhs.gov/clia.9 Review state laws to determine whether your pharmacy can receive CLIA recognition. In addition, under CLIA, pharmacists must follow all Occupational Safety and Health Administration standards for handling and disposing of clinical specimens that potentially contain blood-borne pathogens. Pharmacy design will need to be considered. An area that is at least semiprivate should be used when performing laboratory testing, and a private area is recommended to minimize the potential for patient embarrassment and protect the confidentiality of

conversations. A semiprivate area can be constructed with hanging curtains or standing partitions. A more detailed discussion on changing pharmacy layout can be found in the section on potential obstacles below. An important element in the provision of wellness services is collaboration with other health professionals. For most diseases and patients, this means that the pharmacist should communicate and, when permitted under state law, collaborate with physicians. Most states now grant pharmacists authority to conclude collaborative disease therapy management arrangements with physicians to do some or all of the following: check patients progress with therapy, provide education to patients about their disease, modify therapy when appropriate, and make recommendations to collaborating physicians. The next step is assembly of needed supplies and equipment. For example, pharmacists wanting to offer cholesterol screenings during American Heart Month (February) will need a cholesterol analyzer (e.g., Cholestech), cassettes for the blood specimens, lancets, capillary tubes, gloves, gauze pads, Band-Aids, alcohol swabs, and a biohazard container for contaminated waste. Sometimes, emergency supplies and a written plan for using them will be needed when services are provided. For example, epinephrine will need to be available in case of an allergic reaction following immunization, along with written guidelines on how long patients should remain in the pharmacy following the injection, who is responsible for monitoring them, and what should happen if an adverse reaction occurs. Documentation tools and procedures must be created for service implementation. These include liability waiver forms, physician letters, progress notes, and patient data result forms. As with facilitating wellness services, advertising is a very important step in the provision of services. Next, consider options for compensation. Some examples include having patients pay out-of-pocket for services, having patients submit claims for services rendered through flexible plans such as medical savings accounts, contracting with self-insured employer groups, or a mixture. When the day comes to provide the service, make sure everything is in place so the program runs smoothly. Document all encounters with patients; providing proof of the impact community pharmacists can have on patients lives begins with fully documenting each interaction. Documentation is also necessary for compensation purposes, especially if the pharmacy has contracted with an employer group or an insurance company, and for legal reasons.

Overcoming Potential Obstacles

In an article about health promotion beliefs and practices among pharmacists, Kotecki et al.10 listed the following as the most important perceived barriers to integrating health education and promotion activities into pharmacy practice: constraints while working, lack of reimbursement, physical design of the pharmacy, lack of

Vol. 43, No. 1

January/February 2003

Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association

65

COMMENTARY

Health Observances

information or training, and insufficient management support. Many of these perceived barriers can be conquered so that health promotion within community pharmacies occurs successfully. Compensation is an issue for many pharmacists, although in certain situations (e.g., in suburban areas where discretionary spending on health services is common), patients have been willing to pay out-of-pocket for pharmacists services. The key to receiving cash payment for services is marketing and selling. The pharmacist needs to perceive that his or her time and expertise is worth the money being charged. Most of the time, if a pharmacist believes this and can communicate this conviction to patients, compensation becomes less of an issue. Another avenue pharmacists can take when seeking compensation is to talk with selfinsured employer groups about sponsoring a health screening for their employees at their facilities. Preventive medicine services provided by a pharmacist may potentially benefit an employer by helping to reduce employee sick days and lost productivity. Patients can submit receipts for services rendered by a pharmacist to their insurance company to be paid from flexible reimbursement accounts. Physical design of a pharmacy can often be a challenge. Most health promotions do not require much space, and space outside the pharmacy department may be used for wellness services. For example, place brochures and signs on a small table in front of the pharmacy counter, in the area where patients generally wait to pick up their prescriptions. If the pharmacy is to be remodeled soon, suggest that the design include a semiprivate or private counseling room. The pharmacist can use the extra private space to perform health and wellness activities, such as fingersticks for blood glucose, cholesterol, glycosylated hemoglobin (A1c) or liver enzyme monitoring; immunizations; bone density screening; and counseling about a sensitive medication or medical condition (e.g., HIV medications, opiate dependence). Simple changes in workflow can also help by freeing up pharmacy space and providing time for pharmacists to perform services during certain times of the year (e.g., fall flu shot season). Modifications in workflow include maximizing the use of pharmacy support personnel as state laws allow, processing prescriptions through a linear design (prescription travels from one end of the counter to the other), and using baskets or containers to process and prioritize prescriptions. Pharmacists can participate in continuing education and certification courses to improve their knowledge of and skills in certain subject areas. In the study by Kotecki et al.,10 88% of surveyed pharmacists were willing to participate in continuing education courses to learn more about health promotion and education. Table 3 lists certification programs and other resources that could provide pharmacists with increased health promotion knowledge and skills. Management support is often an issue when starting a new service. The easiest way to find out whether a supervisor will support a service is to ask. If management appears hesitant or negative about facilitating or implementing health promotion activities,

then begin as an advocate and provide patients with information on health topics during patient counseling sessions or provide information in displays or bag stuffers. As pharmacists and managers become more comfortable with health promotion in the pharmacy, activities at the other levels of health promotion participation can be introduced. It is important to always bear in mind, however, that any wellness and health activity can be beneficial for patients.

Examples of Specific Health Observances

With the variety of health observances that occur annually in the United States, pharmacists should have no trouble finding ones that will be easy to promote. Again, Table 4 lists pharmacistfriendly observances for each month. The following sections provide specific ideas on how to carry out health promotion for certain observances, from how to start a specific service to how to improve existing ones. With a few modifications, the advice is applicable to most health observances.

Cardiovascular Disease Many observances relate to cardiovascular disease. February is American Heart Month, May is National High Blood Pressure Education Month and National Stroke Awareness Month, and September is National Cholesterol Education Month.7 Since common risk factors underlie these various conditions, pharmacists can plan the same or similar activities for all their observances. Advocacy activities for cardiovascular health include providing brochures and handouts on risk factors, complications of heart disease, heart-healthy diet and exercise, and explanations of laboratory values. Pharmacists can also act as advocates by providing patients with access to computerized cardiac risk assessment programs or giving patients tests to assess their cardiac risk. Many brochures and tools are available from AHA and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (www.nhlbi.nih.gov/ health/public/heart/index.htm). To act as facilitators in promoting cardiac health, pharmacists can involve other health care professionals in blood pressure screenings, cholesterol screenings, and physical fitness workshops in the pharmacy or during community health fairs. When the pharmacist decides to take on a more active role in preventing cardiovascular disease, services (as permitted under state laws and with CLIA waivers) include blood pressure screenings, cholesterol screenings, and arterial and venous Doppler ultrasound screenings. References that might be helpful for pharmacy providers concerning cardiovascular disease include the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (ATP III)11 and the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.12

66

Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association

January/February 2003

Vol. 43, No. 1

Health Observances

COMMENTARY

Poison Prevention An observance that should be promoted, especially in areas with large pediatric populations, is National Poison Prevention Week in March. Pharmacists are often contacted when a poison has been ingested. During March, pharmacists can serve as poison prevention advocates by providing telephone numbers for poison control centers and distributing tests about home safety and education materials on making the home safer for children to parents. The Consumer Product Safety Commission (www.cpsc.gov) and the American Association of Poison Control Centers (www.aapcc. org/teaching.htm) offer useful patient education materials concerning poison prevention and safety that can be given to pharmacy patrons. To facilitate activities during this week, ask community activists to provide talks and demonstrations within the pharmacy. Since pharmacists are knowledgeable in this area, they can provide such demonstrations in the pharmacy and visit local schools to educate parents and children about the dangers of poisons in the home. Vaccinations With the availability of the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines and the diseases increasingly well-recognized morbidity in older patients, vaccination of Americans aged 50 years and older has become a major public health priority during the months of October, November, December, and January. Pharmacists are in a unique position to advocate influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations. Patients risk status for pneumonia and influenza can be determined easily by reviewing pharmacy records. High-risk patients include people over the age of 65 and persons who have a chronic illness or disease. During Augusts National Immunization Awareness Month and Octobers National Adult Immunization Week, pharmacists can write notes on prescription bags reminding patients to get their influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, provide information on the availability of the vaccines, and dispel myths regarding particular vaccines. Resources for patient education are available from the Immunization Action Coalition (www.immunize.org) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (www.cdc.gov/nip/publications/niiw). To facilitate adult vaccinations, invite nursing groups or the local health department to provide vaccinations in the pharmacy. In states where pharmacists are authorized to provide immunizations, hold influenza and pneumonia clinics and give vaccinations throughout the flu season. Pharmacists can also provide patients with hepatitis B, meningococcus, tetanus, and travel vaccines. For further information about providing vaccines in the community, access the CDCs National Immunization Program Web site (www.cdc.gov/nip) and the American Pharmaceutical Associations immunization Web site (www.aphanet.org/pharm care/immunizationinformation.htm). Diabetes November is American Diabetes Month, and pharmacists can use this occasion to explain to people the risks associated with

development of diabetes and help them learn about ways to control the disease if they already have it. As advocates, pharmacists can provide handouts on diabetes, the risks associated with diabetes, and the special requirements the disease imposes on foot and dental care. Other informational tools that benefit patients with diabetes include blood glucose diaries, carbohydrate counters, and food and exercise diaries. Resources for patient education material can be obtained from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) (www.diabetes.org) and the National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse (www.niddk.nih.gov/health /diabetes/ndic.htm). Pharmacists who work in locations with CLIA waivers can do blood glucose screenings and A1c checks. In states where these activities are not possible, other activities within the pharmacy can be facilitated as part of Diabetes Month, including foot examinations and classes on exercise and stress and how they relate to diabetes. Pharmacists can find useful reference information in the guidelines for diabetes care from ADA, 13 the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the American College of Endocrinology.14

O steoporosis National Osteoporosis Prevention Month (May) is a great time to make pharmacy patrons aware of the dangers of bone loss and the benefits of adequate daily calcium intake and lifestyle modification. As advocates, pharmacists can provide brochures on osteoporosis risk factors and prevention. Pharmacists can also put together lists of different food products that contain calcium, the amount of calcium in each food, and the quantity of each that must be consumed to reach total daily requirements of calcium. Resources for patient education material can be obtained from the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) (www.nof.org). Pharmacists can serve as facilitators by hosting visiting health care professionals to provide, or provide themselves, calcium intake assessments, bone density screenings using heel-, wrist-, or finger-assessment tools (e.g., Sahara and Achilles Express), and classes on fall prevention and medications used for prevention of osteoporosis. Helpful resources include the National Institutes of Healths consensus statement on osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy15 and the NOFs osteoporosis clinical practice guidelines.16

Conclusion

The pharmacist is the most accessible health professional. This accessibility places pharmacists in an excellent position to advocate, facilitate, and implement wellness activities through the provision of information and, in some cases, screenings or disease management. Established national health observances offer a framework for pharmacy-based health initiatives and give pharmacists a chance to make a difference in public health through

Vol. 43, No. 1

January/February 2003

Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association

67

COMMENTARY

Health Observances

7. 2003 National Health Observances. National Health Information Center Web site. Available at: www.health.gov/nhic/pubs/nho.htm. Accessed December 3, 2002. 8. Grabenstein JD, Bonasso J. Health-system pharmacists role in immunizing adults against pneumococcal disease and influenza. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(17 suppl 2):S322. 9. CLIA Program: Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Web site. Available at: http://cms.hhs.gov/clia. Accessed December 3, 2002. 10. Kotecki JE, Elanjian SI, Torabi MR. Health promotion beliefs and practices among pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40:7739. 11. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:248697. 12. National High Blood Pressure Education Program. The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health; 1997. NIH Publication No. 98-4080. 13. American Diabetes Association. Clinical Practice Recommendations 2002. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(suppl 1):1147. 14. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology. Medical Guidelines for the Management of Diabetes Mellitus: The AACE System of Intensive Diabetes Self-Management 2002 Update. Endocr Pract. 2002;8(suppl 1):4182. 15. Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. NIH Consensus Statement. 2000;17(1):145. 16. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Physicians Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 1998.

patient education, preventive medicine, discovery of undiagnosed illness, and improved disease management.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest or financial interests in any product or service mentioned in this article, including grants, employment, gifts, stock holdings, honoraria, consultancies, expert testimony, patents, and royalties.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. 2. National Center for Health Statistics. Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 199894 (NHANES III). Hyattsville, Md: Division of Health Examination Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1997. 3. American Heart Association. 2002 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. Dallas, Tex: American Heart Association; 2001. 4. American Diabetes Association. National Diabetes Fact Sheet [publication online]. Alexandria, Va: American Diabetes Association; 2002. Available at: www.diabetes.org/main/info/facts/facts_natl.jsp. Accessed December 3, 2002. 5. National Osteoporosis Foundation. Disease Statistics: Fast Facts [publication online]. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2002. Available at: www.nof.org/osteoporosis/stats.htm. Accessed December 3, 2002. 6. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2001. Atlanta, Ga: American Cancer Society; 2001. Available at: www.cancer.org/ downloads/STT/F&F2001.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2002.

68

Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association

January/February 2003

Vol. 43, No. 1

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Institutional Biosafety Committee: Role of TheDocument14 pagesInstitutional Biosafety Committee: Role of TheSyeda Wardah NoorNo ratings yet

- RLE Manual EditedDocument68 pagesRLE Manual EditedReymondNo ratings yet

- Hydroxyzine GuidelinesDocument13 pagesHydroxyzine GuidelinesMahim JainNo ratings yet

- BLOOD POST TEST REVIEWDocument11 pagesBLOOD POST TEST REVIEWCherry Ann Garcia DuranteNo ratings yet

- Multimodal Early Onset Stimulation (MEOS) in Rehabilitation After Brain InjuryDocument10 pagesMultimodal Early Onset Stimulation (MEOS) in Rehabilitation After Brain InjuryVendiNo ratings yet

- Tinnitus Today December 1998 Vol 23, No 4Document29 pagesTinnitus Today December 1998 Vol 23, No 4American Tinnitus AssociationNo ratings yet

- Application of Nursing ProcessDocument2 pagesApplication of Nursing ProcessClarence ViboraNo ratings yet

- Ahs 21Document50 pagesAhs 21Ramya SaravananNo ratings yet

- VBAC Guide: Risks, Benefits & ManagementDocument12 pagesVBAC Guide: Risks, Benefits & Managementnyangara50% (2)

- Europass Curriculum Vitae: Personal InformationDocument7 pagesEuropass Curriculum Vitae: Personal InformationAndrei TudoracheNo ratings yet

- Josephine Morrow: Guided Reflection QuestionsDocument3 pagesJosephine Morrow: Guided Reflection QuestionsElliana Ramirez100% (1)

- Why I Desire to Study Medical MicrobiologyDocument2 pagesWhy I Desire to Study Medical MicrobiologyRobert McCaul100% (1)

- Managed Care, Hospitals' Hit Tolerable When Covid Emergency EndsDocument5 pagesManaged Care, Hospitals' Hit Tolerable When Covid Emergency EndsCarlos Mendoza DomínguezNo ratings yet

- Marijuana and EpilepsyDocument17 pagesMarijuana and EpilepsyOmar AntabliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 17 Reproductive SystemDocument15 pagesChapter 17 Reproductive SystemJurugo GodfreyNo ratings yet

- Protocols Sepsis Treatment Stony BrookDocument6 pagesProtocols Sepsis Treatment Stony BrookVicky Chrystine SianiparNo ratings yet

- Geriatric PsychiatryDocument91 pagesGeriatric PsychiatryVipindeep SandhuNo ratings yet

- Cons Study Summary QuiestionsDocument124 pagesCons Study Summary QuiestionsCons Miyu HimeNo ratings yet

- Writing OETDocument4 pagesWriting OETfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Lily Grebe Resume 10Document3 pagesLily Grebe Resume 10api-482765948No ratings yet

- Mod 3 Guidelines in Giving Emergency CAreDocument5 pagesMod 3 Guidelines in Giving Emergency CArerez1987100% (2)

- Periodontology For The Dental Hygienist 4Th Edition Perry Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument41 pagesPeriodontology For The Dental Hygienist 4Th Edition Perry Test Bank Full Chapter PDFshelbyelliswimynjsrab100% (9)

- Continuum CareDocument24 pagesContinuum CareJovelyn EspanolaNo ratings yet

- Study Guide: MandatoryDocument21 pagesStudy Guide: Mandatoryyolanda fransiskaNo ratings yet

- Fading Kitten Emergency Protocol: Hypothermia HypoglycemiaDocument1 pageFading Kitten Emergency Protocol: Hypothermia HypoglycemiaJose Emmanuel MNo ratings yet

- DD Palmer Chronology PDFDocument42 pagesDD Palmer Chronology PDFAdam BrowningNo ratings yet

- Brain Tumors - An Overview: Presented by DR - Raviraj.Ghorpade Consultant Brain & Spine Surgeon BelgaumDocument33 pagesBrain Tumors - An Overview: Presented by DR - Raviraj.Ghorpade Consultant Brain & Spine Surgeon BelgaumRAVIRAJ GHORPADE BELGAUM ADVANCED NEUROSURGERYNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan: Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Scientific Rationale Objectives Interventions Expected OutcomesDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan: Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Scientific Rationale Objectives Interventions Expected OutcomesAsdfghjlNo ratings yet

- Renal Calculi Lesson PlanDocument14 pagesRenal Calculi Lesson PlanVeenasravanthiNo ratings yet

- Kanker Payudara: Dr. Dian Andriani, SPKK, M.Biomed, MarsDocument31 pagesKanker Payudara: Dr. Dian Andriani, SPKK, M.Biomed, Marsdian andriani ratna dewiNo ratings yet