Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Morris Halle 1961 - On The Role of Simplicity in Linguistic Descriptions

Uploaded by

Anders FernstedtOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Morris Halle 1961 - On The Role of Simplicity in Linguistic Descriptions

Uploaded by

Anders FernstedtCopyright:

Available Formats

,Q THE ROLE Of S1MPLJC3TY !

N LINGtHSTIC

DESCRJPTONS1

BY

MORRIS HALLE

.DO3I 1OU IDC VCI DCgDDDg O1 dD3IIdCI C0DCcID WT targfai tere

DdVC DCCH IOOS3 OI 3CDCHC3 LO C3331j IDC sounds O1 6]6CCD. H3 is

hady 3U]IS! 3DCC it I3 almost self-evident lDdI 3]CCCD 3OUDU3 OID VdI1OU3

DI63CC*Dg Cd33C3. HU3, OI D3ldDC,.C DHd 3OUDU3 ID IC WOIG3 r'',

ran, rang 3DdIC lDC ]IO]CIlj of nasalty; I.C., lDC ]IOQII O1 bing ]ICCUCcC

WD 3 CWCICUVCUH, which dCW3 dI O fO lDIOUgD lC DO3C. 1D d 3D18I

1d3DOD, C 3OUDC [H 3DdLC3 WlD lHC 3OUDUS (p] dDC [b] the ]IO]Il OI

DDg IOCUC6C Wl0 d CO3Uc at the ]3. or, d3 ]LODI!C.8D3 WOUC 30, of

PdVDg d D!OJd point of articulation. The )DU1VUUd 3]cCD3OUDC3 CD tDCn

be CdIdClCI2CG d3 CO]CXC3 of Ld3dJI), aIIcUldI IDL3 O articulation

dHC 0HCI ]IO]:IC3, W|)CD LOgCIDCI DdKc U] DC various Cd33DClOIj

1IdHCWOIK3.

DC ]IU]3CU IIdDCWO1K3 C1HCI O1 C0UI5C, JIOU ODC nother, dDC U] to

IC I05CDI ]DODCI1Cd D3 HdVC DOI dgJ60U OD dD) single frame,.rk LHdI I3 IO

b U3CC IH d 1DgU3IC CC3CI1]IOD. In lHC IOOW1Dg 3D3 Ul12C the dis

tinctive feature IIdHCWOIX, WDJCD 3 UUC ]IU3J) lO ODdD jdKOD3OD. L3

LdHCWOIK UUCI5 1JOD ClDCIS in that it C0D33l3 cXCU3VCj O1 DDd!) ]IO]

C!l1C3. 1 WC )COL IDC CJ3IDCI1VC CdIU1C3 d3 OU1 Cd331DCIOI 3CDCLC, WC

commit 0U3C7C3 to 3[OYDg dDUI 3QcC 3OUHCS CXCU31VCj n ItIH3 O1

two-valueC attributes;

i.e., O

]IO]CI\O3 which d given 3OUDU Dd OI Dd

not psse33.

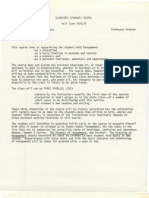

C HHDCI 1D WD1CD IDCVCUd spech 3OUDC3 d1C C1dICl0J1ZCC D lCIH3

of C3I1CIVC CdIULC3 3 1U3I13lCU in gHIC 1. In ID\3 framework 3| .3

CDdIdClCI2U d3 nonvolic, COH3ODdDtdI, DG)gIdVC, DODCOD]dC, strident, HoD

Dd3d, CODIDCdHI, YOCtC33, OI [m] 3 CDdIdClCI2CG d3 nonvocalic, COD3ODdDId,

_IdYC, OUCOH8CI, nonstrident, D3d, LODC0DlHUdDL, VOCcC. LOD3CQUCDI1j,

the 3]DdD6IC 3)DD3 s dDC m by which WC CODVCHL1ODd UC3)gDdlC

\C3c 3OUDC3 3IC HOID1D but 8OOICV1d!JOD3 3ldDCD_ I0I lDC ICdlUIC CODCXC3

_U3l mentioned. I 3 83 C3lU1C COH]CX3, IdIHCI lDdD as 1DU1V3DC CHlI!C3

l. 3l 3]CcCD 3OUDC3 W b ICg3UCC DCI6DdIlC!. It will b 3DOWD IDd\ ID3

GCC3OD opns tHC Wdj 1OF further dUV8DCc3 H UC theory.

We DOI6, DOIC0VCL \H8I WC CdD U3C LHC ICdIUIC3 O I6CI COHVCHCD) IO

C33C3 of 3|CCD 3OUDC3._DU3, IOI ID3lDCc, d 3OUDC3 7CQI63CD\cU in gUC 1

D!ODg IO IHC Cd33 of COD3ODDl3 dDU d3 3UCD they 3Dd7C IDC IC3lUIC3 DOD

vclic dDC consonantl. We DOIC UIICIHOIC L0dLIDC COD5ODdD!3 3 2 c 3

s z]

are the OD) CDC3 ID8 3D8Ic IDC features HODgIdVC dUU 3I!1CCD, OI (p b f v m]

l This work was suppre in pr by the U. S. Ay (Signal Crs), te U.S. Navy

(Ofc of Naval Resrch), ad te U. S. Air Force (Ofce of Sientifc Resarch, Air

R-h ad :velopent Cmw.d), ad in pr by the Nationl Sienc .oudat:on.

89

Reprinted from PROCEEDINGS OF SYMPOSIA iN APPLIED MATHEM...TICS, Vol XII! 1961

Copyright, Americ:n Mathematiccf .ociety 1961, from ?roceedings of Symposia in Applied Mathmatics, V.:!ume X!l, Structure of Language

and its ,"athematicol Aspects, pp. 89-94 All rights reserved

9

MORRIS HALLE

I

l

p

l

b

lml

f Jv

l

k

l

g

I

t

l

d

I

8 jo

I

n

I

s

I

z

l

c

I

3

I

s

I

z

vocalic

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

...~......

...

consonantal + + + + + + + + + + + + +

-

+

+ +

|

.....

|

.....

|

grave + + + + + + +

. . . . . . . . . . .

~...

~

|

..

.=....

l ~

compact

. . . . .

+ +

. . . . . . .

+ + + +

|

......

.........

strident

. . .

+ +

. . . . . . .

+ + +

......

|*

.......

|~

.

nasal

. .

+

. . . . . . . .

+

. . . . . .

.......=.....

11

..

continuant

. . .

+ +

. . . .

+ +

.

+

. .

+ +

.

|

..

|

........

~

..

.

voiced

.

+ +

.

+

.

*

.

+

.

+ +

.

+

.

+

.

Figure 1. Distinctive feature representation of the consonants of English

alone share the features grave and noncompact. On the other hand. [m]

and [s] share no features which would distinguish them from all other con

sonants. If we wanted to designate the class containing the sound [m] and

[s] in distinctive feature terminology, we should have to give a long, cumber

some list of features. We shall say that a set of speech sounds forms a

natural class if fewer features are required to designate the class than to

designate any individual sound in the class. Hence the frst three sets of

sounds form natural classes, whereas the set containing [m] and [s] is not a

natural class.

Jakobsen has shown that in describing the most varied linguistic facts, we

commonly encounter sets of sounds which form natural classes in the distinc

tive feature framework, and that only rarely does one meet classes of sounds

that require long, cumbersome lists of distinctive features for their charac

terization. As a case in point, consider the formation of English noun plurals.

As every English speaker knows in practice, if and only if a noun ends in

[s z s z c 31. the plural is formed by adding the extra syllable [rz]. But as

we have already seen it is precisely this class of consonants that is exhaus

tively characterized by the features nongrave and strident. This coincidence

is important, for the distinctive features were not postulated with the express

purpose of afording a convenient description of the rules for forming the

English pluraL

The preceding remarks imply a special notion of descriptive economy. I

should like to suggest that in the part of a linguistic description that deals

with the phonic aspect of language, economy should be measured by the

number of distinctive features utilized. The fewer features mentioned in a

description, the greater its economy. It is not difcult to show that in simple

cases the criterion does indeed perform as one would expect. Given two

statements of \vhich one applies to all consonants, whereas the other applies

only to strident consonants, we should say without a doubt that the former

is more generaL more economical. This fact would also be refected

in the

number of distinctive features that would have t be mentioned in the two

SIMPLICITY IN LINGUISTIC DESCRIPTIONS

91

statements, for in order to speak of the class of all consonants we need to

mention only the features nonvocalic and consonantal, whereas to designate

the class of strident consonants we must mention the feature strident in

addition to those which designate the class of all consonants. In an analogous

fashion we should consider a rule that applies without restriction, more general

and hence simpler than a rule that applies in specifc contexts only. The

second rule would also require mention of more features, for we would need

to mention at least one distinctive feature in order to characterize the context

in which the second rule applies.

The proposed criterion, however, has other interesting consequences. To

see these we turn again to the formation of plurals of English nouns. The

facts can be stated as follows:

To form the plural:

(a) [i] is added if the stem ends in a sound which is nonvocalic, con

sonantal, nongrave, and strident.

(b) [s] is added if the stem ends in a sound which is nonvocalic, conso

nantal, voiceless, and nonstrident; or nonvocalic, consonantal, voiceless, strident,

and grave.

(c) [z] is added if the stem ends in .a sound which is vocalic; or nonvocalic,

consonantal, voiced, and nonstrident; or nonvocalic, consonantal, voiced, stri

dent, and grave.

It is to be noted that the above three statements are not ordered with

respect to each other, and it is this which makes them so cumbersome. If

. we impose an order on the application of the statements, we can simplify

them markedly as follows:

To form the plural:

(A) [n] is added if the stem ends in a sound which is. non vocalic, con

sonantal, nongrave, and strident.

(B) [s] is added if the stem ends in a sound which is nonvocalic, conso

nantal, and voiceless.

(C) [z] is added.

The relative lengths of the two sets of statements graphically refect thejr

relative simplicity. Ordering, therefore, is mandatory in the present instance,

if we want to satisfy our criterion of simplicity.

The proposal that an order be imposed on the application of the rules is

not novel. Every description that makes use of phrases like "in all other

cases" so as to eliminate the need for spelling out in detail what these "other

cases" might be, makes use of an order among the descriptive statements.

The only novelty here is that the reason for establishing an order is made

explicit: it is a direct consequence of the proposed criterion of simplicity.

Nute, however, that the ordering established by the criterion may not be

totaL since in some instances it will not result in a simplifcation of the de

scription.

Consider now a hypothetical dialect of English2 which difers from the

2 A dialect with almost exactly these features has been described by my colleague Dr.

]. R. Applegate of M. I. T. In order to illustrate my point more clearly, I have modifed

the facts sightly. This modifcation, however, in no way afects the plausibility of the

constructed example.

92 MORRIS HALLE

standard language in the following two respects:

Where the standard language has a continuant consonant in noninitial posi

tion, the dialect has the cognate noncontinuant (stop) consonant.

"here the standard language has several identical noncontinuant consonants

in a word, the dialect replaces all but the frst of these by a glottal stop.

EXAMPLES:

I

cuf (cup)

[k'Ap]

gave (Gabe) [g'eb]

sauce (sought) [s':t)

lies (Lied) [l'ajd]

II

puf

brave

toss

dies

(p' Ap]

[br'eb]

[t':t]

[d'

a

j

d]

III

pup [p' A?]

babe [b'e?]

taught [t':?]

died [d'aj?]

It is to be noted that the dialect admits words with several identical non

continuant consonants, as can be seen in the examples in Column II, but in

every one o{ these examples the second noncontinuant corresponds to a frica

tive in the standard language.

The phonetic peculiarities of this dialect are handled by the following two

ordered rules, which do not function in the standard language:

1. If in a word there are several identical nonvocalic, consonantal non

continuants, aU but the frst become nonvocalic, nonconsonantal noncontinuants

(i.e., glottal stops in distinctive feature terminology). Examples in Column III.

2. In noninitial position, nonvocalic, consonantal continuants become non

continuant.

I believe that this solution, proposed by Applegate, is preferable to the

alternative of postulating a diferent phonological system for the dialect than

for the standard language. It seems to me intuitively more satisfactory to

say, as we have done here, that the dialect difers from the standard language

only in the relatively minor fact of having two additional low-level rules,

rather than to assert-as we should have to do, if we rejected the proposed

solution-that the dialect deviates from the standard language in the much

more crucial sense of having either a diferent phonemic repertoire than the

standard language, or of having a strikingly diferent distribution of phonemes.

It must be stressed that in the proposed solution the ordering of the rules

is absolutely crucial, for if Rule (1) is allowed to operate after Rule (2) the

noncontinuants produced by Rule (2) would be turned into glottal stops by

Rule (1); i.e., the examples in Column II could not be accounted for. vithout

ordering of the rules we are forced to accept the unintuitive alternatives men

tioned above.

If we regard the process of synthesizing an utterance as a sort of calcula

tion whose :nal results are transmitted as instruction to the speech organs,

which in turn produce the acoustical signal that strikes our ears, then the

descriptive rules discussed above are simply steps in the calculation. We

have found that by ordering these steps in a particular way the entire calcu

lation becomes less laborious. We might now ask whether the order of the

rules does not also refect the chronology of their appearance in the language.

Did, for example, the English dialect just discussed pass frst through a stage

where it was identical with the standard language, and then through another

)

)

)

(

\

J

SIMPLICITY IN LINGUISTIC DESCRIPTIONS 93

stage \Vhere it difered from the standard language only in having glottal

stops as required by Rule (1), but lacking the noncontinuants produced by

Rule (2)?

If the order of the rules can be regarded in this light, then the proposed

criterion of descriptive simplicity becomes an important tool for inferring

the history of languages, for it allows us to reconstruct various stages of a

language even in the absence of external evidence such as is provided by

written records or by borrowing in or from other languages.

This way of looking at the phonological rules of a language is anything

but novel. As a matter of fact, I should like to argue that the reconstruc

tion of the history of the Indo-European languages, which is perhaps the

most impressive achievement of nineteenth century linguistics, was possible

only by making use of the proposed criterion of economy to establish an order

among the descriptive statements; the order was then assumed to refect their

relative chronology. This can perhaps be illustrated most graphically by a

discussion of the so-called Laws of Grimm and of Verner, which, with good

reason, are considered among the most solid achievements of Indo-European

studies. The Laws describe stages in the evolution of the Germanic languages

from the Indo-European proto-language, stages which, it should be noted, are

not attested by any external evidence.

The Indo-European proto-language is supposed to have had a single con

tinuant consonant [s], which was voiceless; and a fairly complex system of

noncontinuants, of which for present purposes we need consider only two,

one voiced and the other voiceless. Grimm's and Verner's Laws describe what

happened to these consonants in the course of the evolution of the Germanic

languages.

The part of Grimm's Law that is of interest here consists of two rules

which can be formulated as follows:

G-1. In certain contexts where condition C1 (the precise nature of which

need not concern us here) is satisfed, nonconvocalic, consonantal, voiceless

noncontinuants become continuant. (It is by virtue of this Law that English

jve is said to be cognate with Greek pente, Russian pjat', and Sanskrit panca.)

G-2. Non vocalic, consonantal, voiced roncontinuants become voiceless.

(G-2 establishes the correspondence between English ten and Greek deka,

Russian desjat', and Sanskrit daa.)

The handbooks tell us that these two rules came into the language in the

order indicated, because-and this is particularly important here, for there

is no other evidence-if G-2 had operated before G-1 the voiceless continuants

produced by G-2 would have become noncontinuants as a consequence of rule

G-1. This argumentation, however, is identical with the reasoning which we

gave above in justifying the ordering of the rules in the example from the

English dialect. The only new factor here is that the order of the rules,

which in the English example had no chronological signifcance, is given such

signifcance here.

At some later time Germanic underwent the efects of Verner's Law which

can be formulated as follows:

V. In contexts where C2 holds, nonvocalic, consonantal, voiceless con-

94 MORRIS HALLE

tinuants become voiced.

If we believe with the majority that Verner's Law was later than G-1,

then we must assume that at this stage the language possessed voiceless

continuants from two sources: the [s] which descended unchanged from the

Indo-European proto-language, and the voiceless continuants produced by the

operation of Grimm's Law (Rule G-1). The fact that Verner's La,., applies

\vithout distinction to voiceless continuants from both sources is always cited

as the crucial evidence in favor of regarding Verner's La-.v later than Grimm's

Law.

This evidence, however, carries weight only if we accept a criterion

of descriptive economy much like the one that was stated above. for-as in

the case of the plural of English nouns-the facts can also be accounted for

fully by the following three unordered rules:

In contexts where both condition C1 and Cz are satisfed, nonvocalic, con

sonantal, voiceless noncontinuants become voiced and continuant.

In contexts where C1 but not Cz is satisfed, nonvocalic, consonantal, voice

less continuants become continuant.

In context Cz, [s] (i.e., its total feature specifcation, which requires men

tioning a fair number of features) becomes voiced.

By the proposed criterion of simplicity we must reject the unordered rules,

for they require more features than the ordered alternatives G-1 and V.

Since there is no external evidence that the language changed in the manner

indicated by Grimm's and Verner's Laws, the acceptance of these Laws as

historical fact is based wholly on considerations of simplicity. But these are

very weighty considerations indeed, for as Professor Quine has remarked, we

construct the picture of our world on the basis of "what is plus the simPlicity

of the laws whereby we describe and extrapolate what is."

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY,

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

)

) .

)

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Machine Age, by Norbert Wiener, 1949Document8 pagesThe Machine Age, by Norbert Wiener, 1949Anders Fernstedt100% (1)

- Hem Tiwari Vs Nidhi Tiwari Mutual Divorce - Revised VersionDocument33 pagesHem Tiwari Vs Nidhi Tiwari Mutual Divorce - Revised VersionKesar Singh SawhneyNo ratings yet

- REBIRTH, REFORM, and RESILIENCE - Universities in Transition 1300-1700 (Ohio State University Press 1984)Document384 pagesREBIRTH, REFORM, and RESILIENCE - Universities in Transition 1300-1700 (Ohio State University Press 1984)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Dravyaguna VijaDocument1,095 pagesDravyaguna VijaSilas Chagas100% (1)

- Operations Management Success FactorsDocument147 pagesOperations Management Success Factorsabishakekoul100% (1)

- Internal Credit Risk Rating Model by Badar-E-MunirDocument53 pagesInternal Credit Risk Rating Model by Badar-E-Munirsimone333No ratings yet

- Dynamics of Bases F 00 BarkDocument476 pagesDynamics of Bases F 00 BarkMoaz MoazNo ratings yet

- Staal, Frits - A Reader On The Sanskrit Grammarians (1972 OCR)Document583 pagesStaal, Frits - A Reader On The Sanskrit Grammarians (1972 OCR)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Rune E.A. Johansson - The Psychology of Nirvana (1969 OCR)Document137 pagesRune E.A. Johansson - The Psychology of Nirvana (1969 OCR)Anders Fernstedt100% (2)

- Audience AnalysisDocument7 pagesAudience AnalysisSHAHKOT GRIDNo ratings yet

- Leo Wiener 1921 - History of Arabico-Gothic Culture (Vol. 4 OCR)Document466 pagesLeo Wiener 1921 - History of Arabico-Gothic Culture (Vol. 4 OCR)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Honour - Julian Pitt-Rivers, Radcliffe-Brown Lecture in Social Anthropology, British Academy, 1995Document24 pagesHonour - Julian Pitt-Rivers, Radcliffe-Brown Lecture in Social Anthropology, British Academy, 1995Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Country-House Radicals 1590-1660 by H. R. Trevor-Roper (History Today, July 1953)Document8 pagesCountry-House Radicals 1590-1660 by H. R. Trevor-Roper (History Today, July 1953)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- A Case Study On Implementing ITIL in Bus PDFDocument7 pagesA Case Study On Implementing ITIL in Bus PDFsayeeNo ratings yet

- Ashforth & Mael 1989 Social Identity Theory and The OrganizationDocument21 pagesAshforth & Mael 1989 Social Identity Theory and The Organizationhoorie100% (1)

- Rhodes Solutions Ch4Document19 pagesRhodes Solutions Ch4Joson Chai100% (4)

- A Yorkshire Town - The Making of DoncasterDocument142 pagesA Yorkshire Town - The Making of DoncasterAnders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- ANNAT SÄTT ATT FULLGÖRA SKOLPLIKTEN? en Intervjustudie Om Hemundervisning Av Glorija Vaitkeviciute 2018Document49 pagesANNAT SÄTT ATT FULLGÖRA SKOLPLIKTEN? en Intervjustudie Om Hemundervisning Av Glorija Vaitkeviciute 2018Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- CCS Early British Ai EdinburghDocument20 pagesCCS Early British Ai EdinburghAnders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- 2006 LED Book Pictures - High Quality (80 MB) NonocrDocument105 pages2006 LED Book Pictures - High Quality (80 MB) NonocrAnders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Meta-Programming - A Software Production Method by Charles SimonyiDocument146 pagesMeta-Programming - A Software Production Method by Charles SimonyiAnders Fernstedt100% (1)

- What I Learned From Karl Popper - An Interview With E. H. Gombrich (By Paul Levinson)Document18 pagesWhat I Learned From Karl Popper - An Interview With E. H. Gombrich (By Paul Levinson)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- William F. Clocksin - A Social Constructionist Framework For Artificial IntelligenceDocument1 pageWilliam F. Clocksin - A Social Constructionist Framework For Artificial IntelligenceAnders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- The Discovery of The Mind in Greek Philosophy and LiteratureDocument18 pagesThe Discovery of The Mind in Greek Philosophy and LiteratureAnders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Peter Drucker's Syllabus For The Management Process, 1974/75Document4 pagesPeter Drucker's Syllabus For The Management Process, 1974/75Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- AISB 2000 - Proceedings, Symposium On How To Design A Functioning MindDocument179 pagesAISB 2000 - Proceedings, Symposium On How To Design A Functioning MindAnders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- William F. Clocksin - A Narrative Architecture For Functioning MindsDocument8 pagesWilliam F. Clocksin - A Narrative Architecture For Functioning MindsAnders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Irwin Primer - Erasmus Darwin's Temple of Nature - Progress, Evolution, and The Eleusinian Mysteries (JHI 1964 OCR)Document20 pagesIrwin Primer - Erasmus Darwin's Temple of Nature - Progress, Evolution, and The Eleusinian Mysteries (JHI 1964 OCR)Anders Fernstedt0% (1)

- Hans Helander - Neo-Latin Studies, Significance and Prospects (2001)Document98 pagesHans Helander - Neo-Latin Studies, Significance and Prospects (2001)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Peter Drucker - The New Society (Ocr)Document187 pagesPeter Drucker - The New Society (Ocr)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- William F. Clocksin - Knowledge Representation and Myth (1995) OCRDocument10 pagesWilliam F. Clocksin - Knowledge Representation and Myth (1995) OCRAnders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Leo Wiener 1920 - History of Arabico-Gothic Culture (Vol. 3 OCR)Document363 pagesLeo Wiener 1920 - History of Arabico-Gothic Culture (Vol. 3 OCR)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Leo Wiener 1917 - History of Arabico-Gothic Culture (Vol. 1 OCR)Document340 pagesLeo Wiener 1917 - History of Arabico-Gothic Culture (Vol. 1 OCR)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Frits Staal - Artifical Languages Across Sciences and Civilizations (2006, OCR)Document53 pagesFrits Staal - Artifical Languages Across Sciences and Civilizations (2006, OCR)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Leo Wiener 1919 - History of Arabico-Gothic Culture (Vol. 2 OCR)Document420 pagesLeo Wiener 1919 - History of Arabico-Gothic Culture (Vol. 2 OCR)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Poverty of Stimulus - Unfinished Business Noam Chomsky (2012, Universals and Variation)Document14 pagesPoverty of Stimulus - Unfinished Business Noam Chomsky (2012, Universals and Variation)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Linguistics As Chemistry - The Substance Theory of Semantic Primes - Arnold Zwicky, in A Festschrift For Morris Halle (1973)Document19 pagesLinguistics As Chemistry - The Substance Theory of Semantic Primes - Arnold Zwicky, in A Festschrift For Morris Halle (1973)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Popper's Situational Analysis and Contemporary Sociology - Hedström, Swedberg, Udéhn 1998Document26 pagesPopper's Situational Analysis and Contemporary Sociology - Hedström, Swedberg, Udéhn 1998Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- Listening LP1Document6 pagesListening LP1Zee KimNo ratings yet

- Leibniz Integral Rule - WikipediaDocument70 pagesLeibniz Integral Rule - WikipediaMannu Bhattacharya100% (1)

- Pengaruh Implementasi Sistem Irigasi Big Gun Sprinkler Dan Bahan Organik Terhadap Kelengasan Tanah Dan Produksi Jagung Di Lahan KeringDocument10 pagesPengaruh Implementasi Sistem Irigasi Big Gun Sprinkler Dan Bahan Organik Terhadap Kelengasan Tanah Dan Produksi Jagung Di Lahan KeringDonny Nugroho KalbuadiNo ratings yet

- Downloaded From Uva-Dare, The Institutional Repository of The University of Amsterdam (Uva)Document12 pagesDownloaded From Uva-Dare, The Institutional Repository of The University of Amsterdam (Uva)Iqioo RedefiniNo ratings yet

- Portal ScienceDocument5 pagesPortal ScienceiuhalsdjvauhNo ratings yet

- (123doc) - Internship-Report-Improving-Marketing-Strategies-At-Telecommunication-Service-Corporation-Company-VinaphoneDocument35 pages(123doc) - Internship-Report-Improving-Marketing-Strategies-At-Telecommunication-Service-Corporation-Company-VinaphoneK59 PHAN HA PHUONGNo ratings yet

- Physics 401 Assignment # Retarded Potentials Solutions:: Wed. 15 Mar. 2006 - Finish by Wed. 22 MarDocument3 pagesPhysics 401 Assignment # Retarded Potentials Solutions:: Wed. 15 Mar. 2006 - Finish by Wed. 22 MarSruti SatyasmitaNo ratings yet

- Importance of SimilesDocument10 pagesImportance of Similesnabeelajaved0% (1)

- Direct Shear TestDocument10 pagesDirect Shear TestRuzengulalebih ZEta's-ListikNo ratings yet

- SOW Form 4 2017Document8 pagesSOW Form 4 2017ismarizalNo ratings yet

- My Testament On The Fabiana Arejola M...Document17 pagesMy Testament On The Fabiana Arejola M...Jaime G. Arejola100% (1)

- UTS - Comparative Literature - Indah Savitri - S1 Sastra Inggris - 101201001Document6 pagesUTS - Comparative Literature - Indah Savitri - S1 Sastra Inggris - 101201001indahcantik1904No ratings yet

- Signal WordsDocument2 pagesSignal WordsJaol1976No ratings yet

- University Students' Listening Behaviour of FM Radio Programmes in NigeriaDocument13 pagesUniversity Students' Listening Behaviour of FM Radio Programmes in NigeriaDE-CHOICE COMPUTER VENTURENo ratings yet

- Theories of ProfitDocument39 pagesTheories of Profitradhaindia100% (1)

- Course Outline IST110Document4 pagesCourse Outline IST110zaotrNo ratings yet

- Influence of Contours On ArchitectureDocument68 pagesInfluence of Contours On Architecture蘇蘇No ratings yet

- Problem Set 12Document5 pagesProblem Set 12Francis Philippe Cruzana CariñoNo ratings yet

- Reducing Work Related Psychological Ill Health and Sickness AbsenceDocument15 pagesReducing Work Related Psychological Ill Health and Sickness AbsenceBM2062119PDPP Pang Kuok WeiNo ratings yet

- Wave Optics Part-1Document14 pagesWave Optics Part-1Acoustic GuyNo ratings yet