Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pakistan and Centre Stage at The NATO Summit

Uploaded by

Tom KirkOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pakistan and Centre Stage at The NATO Summit

Uploaded by

Tom KirkCopyright:

Available Formats

Pakistan and Centre Stage at the NATO Summit

Tom Kirk - 22nd May 2012

After much speculation over his countrys inclusion, Pakistans president Asif Ali Zardari attended the recent NATO summit in Chicago. His last minute appearance acknowledged that NATO can neither sustain the fight nor continue to plan the retreat from Afghanistan without Pakistans cooperation. It also confirmed that, whether they come from multinational organisations or bilaterally from nations such as the US, Pakistan cannot afford to ignore the international communitys overtures. Although there are many reasons for both sides positions, it is arguably Pakistans ongoing reliance on the international communitys financial assistance that deserved to be centre stage at Chicago. The reasons for the will-they-wont-they manoeuvring on Pakistans inclusion at the summit reportedly lay in ongoing talks over the opening of NATO supply lines following their closure late last year. According to Pakistans Foreign Minister Hina Rabbani Khar the closure allowed her government to make a point after the killing of twenty four soldiers in Salala in the North Western border regions by US warplanes. Although not openly admitted, the decision was also likely to have been a response to repeated embarrassments for Pakistan - including last years unopposed US mission targeting Osama bin Ladens hideout in Abbottabad and the repatriation of CIA contractor Raymond Davis before he could stand trial for shooting two men in Lahore. However, after the creation of new guidelines for bi-lateral agreements with the US, NATOs supply trucks have slowly begun to resume their haul over the Khyber Pass and the organisations spokesmen are once again describing Pakistan as having an important role to play in Afghanistans future. Along with wishing to use Pakistans roads to continue their withdrawal, NATO member countries are acutely aware that many of Afghanistans diverse insurgent groups find refuge in Pakistans vast border regions and sprawling metropolises. As individual member states arguably distance themselves from any pretensions to be engaged in state-building in Afghanistan, the only justification for keeping troops in the region beyond 2014 will be the elimination of these elements before they can plan attacks locally or further afield. However, destabilising insurgent bases and arresting international jihadists requires locating them among a population of 180 million; a complex task that can only be achieved with the close coordination of Pakistans security establishment. It also necessitates the acquiescence of the largely autonomous and, in some instances, heavily armed people of Pakistan, many of whom tacitly support insurgents in Afghanistan and would be willing to interdependently take up arms against any US presence in their own country. Thus, NATO member states realise that Pakistan is likely to remain on their radars long after the Wests most recent military intervention in Afghanistan has become a historical episode. For their part, Pakistans elite understand that they benefit from the financial assistance that periodically floods into the country. Indeed, Pakistan watchers are increasingly pointing to the effects of international aid on Pakistans political economy. They suggest that, whether as members of democratic governments or officers of the military-bureaucratic oligarchy,

Pakistans elites have long been able to use foreign assistance to maintain the economic and political status quo. They highlight that although Pakistan has received more than $60 billion in direct aid from the US alone since 1948, it remains one of the most heavily militarised and impoverished countries on the planet. Furthermore, with only 1.7 million people currently registered to pay income tax, Pakistan recently posted a worrying tax to GDP ratio of 8.6, lower even than Afghanistan. These figures have prompted analysts to describe Pakistan as a rentier state, deriving income from inefficient state run companies and generous foreign assistance programmes rather than a sustainable tax base. This status enables successive ruling oligarchies to shun democratic accountability, buy votes and maintain their domestic patronage networks. The latter is perhaps best illustrated by reports that Pakistans two largest contemporary social safety net programmes, the partially foreign funded Benazir Income Support Programme and the Zakat Programme, are perceived by ordinary Pakistanis to be slush funds for domestic patronage politics and, in the case of the former, an instrument of international imperialism. From 2001 to 2010 US aid to Pakistan amounted to over $18 billion. Furthermore, through the Enhanced Partnership with Pakistan Act of 2009 the US has pledged another $7 billion over five years. Although this figure is relatively low, amounting to less than 1 % of Pakistans GDP or around two thirds of US spending on the Afghan army a year, the inflow of money arguably entrenches Pakistans political economy of patronage and power, and continues a trend in which Pakistans elite are buttressed by foreign funds in times of flux and crisis. Albeit mostly covert, the last time foreign assistance was channelled into Pakistan on such a scale was during the Soviets occupation of Afghanistan. This not only served the Wests geo-strategic ambitions vis--vis the spread of communism, but also allowed General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haqs Islamist regime to retain power through patronage and coercion. The General used foreign money to militarise large swathes of Pakistans border regions and pursue a nationwide programme of Islamisation that included the infamous Hudood Ordinance; legislation which has since been criticised by Western observers for encouraging the rape and stoning of women. The episode also led to Pakistans use of jihadist groups in Afghanistan long after the Soviets fled in 1989 and in Kashmir from 1987. Thus, it was one of the formative moments of the global jihadist movement that continues to allow outfits such as Al-Qaeda to find an ideological and material home in Pakistan today. As during Zias regime, contemporary foreign assistance is offered to Pakistan as an incentive to pursue the Wests interests. However, it arguably encourages Pakistans elites to view party politics as a game of probability and state institutions as tools with which to reward clients and punish rivals. Accordingly, Anatol Lievens recent book suggests that elites are left with few incentives to engage in meaningful social reforms or to pay and collect taxes. Foreign assistance may also help them to ignore the violent and domestically focussed Islamist groups which are gaining popularity within their vastly unequal and polarised society. Although it is unlikely that Al-Qeada or its affiliates could ever inspire large numbers of Pakistanis to join their cause, these newer alliances of domestic militant Islamist organisations are a potent political force; holding well attended political rallies that the central government appears reluctant to oppose. At these events the groups feed off the elites ignorance of the widespread discontent among their own clients and speak the political language of the man on the street. This includes portraying elites as compliant with the war in Afghanistan and stooges of foreign powers. In sum, democratic governance is delegitimised for being un-Islamic. The groups are also able to promote a brand of localised justice that mixes Islamic and tribal laws into a particularly exclusionary and violent jurisprudence that

further threatens the rights of women and minority groups. These worrying developments are compounded by a number of domestic and international factors. At home, Pakistan faces a rapidly expanding population with roughly 63% of people below the age of 25. Largely unemployed, they are increasingly aware of the social inequality that has long characterised their country. Furthermore, given increased access to media and education they appear unwilling to accept the lives of semi-servitude that their fathers are likely to have lived. Unsurprisingly, many are attracted to political, criminal and militant organisations that promise everything from a vote and a livelihood, to a gun, swift Islamic justice and an alternative to the current exclusive political system. While this can manifest itself in support for new political pretenders such as Imran Khan, it also arguably feeds support for the murder of politicians such as Salmaan Taseer, provides recruits for Karachis violent criminal gangs and drives incidents such as 2009s takeover of the Swat Valley by home grown militant movements. These are trends that are unlikely to subside unless ordinary people believe they have a stake in Pakistans economic and political systems. However, there is little evidence that Pakistans elites are willing to give up the political privileges, vast wealth and access to opportunities that they enjoy. Internationally, Western nations facing austerity are rethinking the way they conduct foreign policy. In particular, they are searching for inexpensive methods of engaging fragile states that they view as simultaneously in need of development and as posing a international security threat. On the one hand, this is likely to mean less money will simply be handed to domestic elites to spend as they see fit and conditional assistance will become commonplace. This can already be seen in the British prime ministers controversial 2011 outburst over Department of International Development spending in Pakistan and in the USs recent decision to withdraw military aid to encourage Pakistan to tackle insurgent groups more aggressively. On the other hand, it suggests that countries such as the US will look to maintain and even extend the use of weaponised drones in regions they cannot politically or financially afford to enter. If this happens, which early reporting from the NATO summit seems to indicate, Pakistan will have to find a way to satisfy the US that it can eliminate insurgents itself or persuade its agitated population that the US attacks are in their interest, which, once again, will only be possible if ordinary people believe that they have a stake in the countrys future. However, while Pakistan can make the case that aggressively tackling insurgents is impossible given the border regions history of failed military ventures, the second option of pursuing widespread political, social and fiscal reforms seems to have escaped the comprehension of Pakistani and international policymakers. This is worrying given both the countrys recent turn towards militancy and the Wests newfound enthusiasm for what can be described as inexpensive and impersonal foreign policy. However, as has been shown elsewhere, events such as that recently held in Chicago offer opportunities for international organisations, individual countries and recipient governments to discuss their relations in private, with each able to use their various leverages to hash out alternatives to failing trajectories. In the case of Pakistan, we can only hope that the political posturing that foreshadowed their inclusion at Chicago did not continue inside the convention centre. Tom Kirk is a researcher with the Human Security and Civil Society Research Unit at the LSE.

You might also like

- Pakistan Americas Problem PartnerDocument3 pagesPakistan Americas Problem PartnerWaleed AliNo ratings yet

- Pakistan-The Most Dangerous Place in The WorldDocument5 pagesPakistan-The Most Dangerous Place in The WorldwaqasrazasNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Foreign Policy Towards Afghanistan ThesisDocument7 pagesPakistan Foreign Policy Towards Afghanistan ThesisOnlinePaperWritingServicesGarland100% (2)

- US and PakistanDocument2 pagesUS and PakistanMuhammad EssaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Foreign Policy ChallangesDocument4 pagesPakistan Foreign Policy ChallangesJawad JuttNo ratings yet

- PAK America RelationsDocument5 pagesPAK America RelationsHammadZenNo ratings yet

- Just Say No To PakistanDocument4 pagesJust Say No To Pakistanikonoclast13456No ratings yet

- Trouble Across The Western BorderDocument7 pagesTrouble Across The Western Borderzahidchattha15No ratings yet

- Cooperation On Drones?Document6 pagesCooperation On Drones?Ussama YasinNo ratings yet

- December 1: Dawn: A Chaotic ResponseDocument9 pagesDecember 1: Dawn: A Chaotic ResponseGNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Polarization in PakistanDocument13 pagesEthnic Polarization in PakistanSanya TiwanaNo ratings yet

- April 2010Document19 pagesApril 2010Shaneela Rowah Al-QamarNo ratings yet

- Proxy Wars in PakistanDocument2 pagesProxy Wars in Pakistanalisyed37No ratings yet

- The Turning PointDocument2 pagesThe Turning Pointshazzz_222No ratings yet

- SocialDocument4 pagesSocialFMWNo ratings yet

- Review by Jon P. DorschnerDocument3 pagesReview by Jon P. DorschnerMasroor ButtNo ratings yet

- Challenges Loom For PostDocument5 pagesChallenges Loom For PostAbdul NaeemNo ratings yet

- Baluchistan: Crossroads of US Proxy WarDocument5 pagesBaluchistan: Crossroads of US Proxy Warikonoclast13456No ratings yet

- Different Articles Related To Foreign PolicyDocument15 pagesDifferent Articles Related To Foreign PolicyDawood KhanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan: Prospects For Social CohesionDocument4 pagesPakistan: Prospects For Social CohesionAsif KureishiNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Foreign Policy Trends and ChallengesDocument68 pagesPakistan's Foreign Policy Trends and ChallengesAli AhmadNo ratings yet

- Shafiq Scholerly PaperDocument13 pagesShafiq Scholerly PaperSHAFIQNo ratings yet

- Pakistan: Violence vs. Stability: A National Net AssessmentDocument205 pagesPakistan: Violence vs. Stability: A National Net AssessmentHome TuitionNo ratings yet

- Pak US Relations LatestDocument2 pagesPak US Relations LatestAsaad AreebNo ratings yet

- Pakistan and The Future of US Policy Cato Policy AnalysisDocument28 pagesPakistan and The Future of US Policy Cato Policy AnalysisFarrukh KhanNo ratings yet

- Balkanizing PakistanDocument5 pagesBalkanizing PakistanKhalid MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Mobilizing-Pakistani-DiasDocument9 pagesMobilizing-Pakistani-DiasIrfan EssazaiNo ratings yet

- 31st OCT 2013 - Can Pakistan Survive Without US AidDocument4 pages31st OCT 2013 - Can Pakistan Survive Without US AidShafiq KhanNo ratings yet

- Hege COincardsDocument8 pagesHege COincardsGabriel KooNo ratings yet

- Backgrounder #122: Pakistan: The Rising Soviet Threat and Declining U.S. Credibility by Phillips, James ADocument15 pagesBackgrounder #122: Pakistan: The Rising Soviet Threat and Declining U.S. Credibility by Phillips, James Aasifthezabian6241No ratings yet

- The U S PakistanRelationshipintheYearAheadDocument5 pagesThe U S PakistanRelationshipintheYearAheadnajeebcr9No ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument4 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentxshabanNo ratings yet

- Dawn EditorialDocument4 pagesDawn EditorialMuhammad AdeelNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Foreign Policy Trends Op 54Document43 pagesPakistan Foreign Policy Trends Op 54Shanzay KhanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Foreign PolicyDocument9 pagesPakistan Foreign PolicyA D BalochNo ratings yet

- WP Pakistananditsmilitants WhoismainstreamwhomDocument39 pagesWP Pakistananditsmilitants WhoismainstreamwhomnasserNo ratings yet

- Pakistan - U.S. RelationsDocument101 pagesPakistan - U.S. RelationsJahanzeb ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Why The Pakistan Army Is Here To Stay: Prospects For Civilian GovernanceDocument18 pagesWhy The Pakistan Army Is Here To Stay: Prospects For Civilian GovernanceSAMI UR REHMANNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Is Facing A Hard Time of LifeDocument4 pagesPakistan Is Facing A Hard Time of LifeDr.Masood Tariq ArainNo ratings yet

- Pakistan: Needing Institutionalized Insight in Public PolicyDocument4 pagesPakistan: Needing Institutionalized Insight in Public Policyqudratulla42No ratings yet

- Hybrid WarfareDocument3 pagesHybrid WarfareMaryia IjazNo ratings yet

- 4 New Era in Pakistans Foreign Policy Problems and ProspectsDocument27 pages4 New Era in Pakistans Foreign Policy Problems and ProspectsIshfaque AhmedNo ratings yet

- Terrorism in Pakistan Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesTerrorism in Pakistan Literature Reviewgw259gj7100% (1)

- Pakistan MAR October 2009Document65 pagesPakistan MAR October 2009InterActionNo ratings yet

- US Pakistan RelationsDocument7 pagesUS Pakistan RelationsAadil JuttNo ratings yet

- India and Crises Hit PakistanDocument11 pagesIndia and Crises Hit PakistansandeepNo ratings yet

- Share DOC-20200629-WA0003.Document24 pagesShare DOC-20200629-WA0003.Faisal SharifNo ratings yet

- Sino-Pakistan Relations: Repercussions For India: Journal of The Research Society of PakistanDocument11 pagesSino-Pakistan Relations: Repercussions For India: Journal of The Research Society of PakistanRajabNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Polarized Politics Challenge DemocracyDocument34 pagesPakistan's Polarized Politics Challenge DemocracyZakir Hussain ChandioNo ratings yet

- How Will Elections Impact Pakistan Foreign Policy.Document9 pagesHow Will Elections Impact Pakistan Foreign Policy.Aadil JuttNo ratings yet

- The Best Way Forward On The New AfghanistanDocument8 pagesThe Best Way Forward On The New Afghanistanneat gyeNo ratings yet

- Obama On Afpak PolicyDocument9 pagesObama On Afpak Policyanupamalok07No ratings yet

- Pakistan in 2020Document15 pagesPakistan in 2020ikonoclast2002No ratings yet

- A Fortress Built On Quicksand: U.S. Policy Toward Pakistan, Cato Policy AnalysisDocument15 pagesA Fortress Built On Quicksand: U.S. Policy Toward Pakistan, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- After Obama Article Ny TimesDocument4 pagesAfter Obama Article Ny TimesZeeshan KhatriNo ratings yet

- Authoritarianism and Legitimation of State Power in Pakistan PDFDocument38 pagesAuthoritarianism and Legitimation of State Power in Pakistan PDFShahzad AmarNo ratings yet

- Pakistan at the Crossroads: Domestic Dynamics and External PressuresFrom EverandPakistan at the Crossroads: Domestic Dynamics and External PressuresRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Monitoring and Evaluation of Sediment Control Structure (Sabo Dam)Document8 pagesMonitoring and Evaluation of Sediment Control Structure (Sabo Dam)Ricky PriyatmokoNo ratings yet

- Your Money Personality Unlock The Secret To A Rich and Happy LifeDocument30 pagesYour Money Personality Unlock The Secret To A Rich and Happy LifeLiz Koh100% (1)

- Bell I Do Final PrintoutDocument38 pagesBell I Do Final PrintoutAthel BellidoNo ratings yet

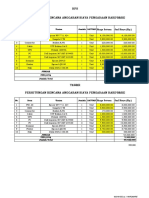

- HPS Perhitungan Rencana Anggaran Biaya Pengadaan Hardware: No. Item Uraian Jumlah SATUANDocument2 pagesHPS Perhitungan Rencana Anggaran Biaya Pengadaan Hardware: No. Item Uraian Jumlah SATUANYanto AstriNo ratings yet

- The RF Line: Semiconductor Technical DataDocument4 pagesThe RF Line: Semiconductor Technical DataJuan David Manrique GuerraNo ratings yet

- Rev Transcription Style Guide v3.3Document18 pagesRev Transcription Style Guide v3.3jhjNo ratings yet

- Sample Detailed EvaluationDocument5 pagesSample Detailed Evaluationits4krishna3776No ratings yet

- Master Your FinancesDocument15 pagesMaster Your FinancesBrendan GirdwoodNo ratings yet

- Asia Competitiveness ForumDocument2 pagesAsia Competitiveness ForumRahul MittalNo ratings yet

- Mariam Kairuz property dispute caseDocument7 pagesMariam Kairuz property dispute caseReginald Matt Aquino SantiagoNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of The White Nationalist MovementDocument73 pagesA Brief History of The White Nationalist MovementHugenNo ratings yet

- Bhushan ReportDocument30 pagesBhushan Report40Neha PagariyaNo ratings yet

- Exam SE UZDocument2 pagesExam SE UZLovemore kabbyNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint Lectures For Principles of Macroeconomics, 9E by Karl E. Case, Ray C. Fair & Sharon M. OsterDocument24 pagesPowerpoint Lectures For Principles of Macroeconomics, 9E by Karl E. Case, Ray C. Fair & Sharon M. OsterJiya Nitric AcidNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Succession LawDocument2 pagesCase Study - Succession LawpablopoparamartinNo ratings yet

- XSI Public Indices Ocean Freight - January 2021Document7 pagesXSI Public Indices Ocean Freight - January 2021spyros_peiraiasNo ratings yet

- 001 Joseph Vs - BautistacxDocument2 pages001 Joseph Vs - BautistacxTelle MarieNo ratings yet

- 20 Laws by Sabrina Alexis and Eric CharlesDocument58 pages20 Laws by Sabrina Alexis and Eric CharlesLin Xinhui75% (4)

- Misbehaviour - Nges Rgyur - I PDFDocument32 pagesMisbehaviour - Nges Rgyur - I PDFozergyalmoNo ratings yet

- Bazi BasicopdfDocument54 pagesBazi BasicopdfThe3fun SistersNo ratings yet

- Ck-Nac FsDocument2 pagesCk-Nac Fsadamalay wardiwiraNo ratings yet

- Review 6em 2022Document16 pagesReview 6em 2022ChaoukiNo ratings yet

- Unitrain I Overview enDocument1 pageUnitrain I Overview enDragoi MihaiNo ratings yet

- Special Blood CollectionDocument99 pagesSpecial Blood CollectionVenomNo ratings yet

- General Physics 1: Activity Title: What Forces You? Activity No.: 1.3 Learning Competency: Draw Free-Body DiagramsDocument5 pagesGeneral Physics 1: Activity Title: What Forces You? Activity No.: 1.3 Learning Competency: Draw Free-Body DiagramsLeonardo PigaNo ratings yet

- Qatar Star Network - As of April 30, 2019Document7 pagesQatar Star Network - As of April 30, 2019Gends DavoNo ratings yet

- Inferences Worksheet 6Document2 pagesInferences Worksheet 6Alyssa L0% (1)

- Treatment of Pituitary Adenoma by Traditional Medicine TherapiesDocument3 pagesTreatment of Pituitary Adenoma by Traditional Medicine TherapiesPirasan Traditional Medicine CenterNo ratings yet

- Commercial Contractor Exam Study GuideDocument7 pagesCommercial Contractor Exam Study Guidejclark13010No ratings yet