Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessment After Trauma

Uploaded by

Tatiana BuianinaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessment After Trauma

Uploaded by

Tatiana BuianinaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Traumatic Stress February 2012, 25, 9497

BRIEF REPORT

PRISM (Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure): A New Method for the Assessment of Suffering After Trauma

Lutz Wittmann,1 Ulrich Schnyder,1 and Stefan B chi2 u

1

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 2 Clinic for Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics Hohenegg, Meilen, Switzerland

This pilot study tested the validity of a 1-item visual assessment method originally developed to evaluate suffering in chronic illness that has been adapted for use with patients who have been exposed to traumatic events. The Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure (PRISM) was administered 5 times during the course of a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment outcome study (N = 29). The PRISM scores declined signicantly under trauma-focused psychotherapy and differentiated between participants with and without PTSD diagnoses. Test-retest reliability over a 6-month period was high (r = .85). PRISM showed signicant correlations with measures of PTSD, depression, and psychopathology symptom load (r = .38 to r = .81; convergent validity). At the same time, PRISM was not signicantly related to trauma history (discriminant validity). Illustrations of symptom time courses indicated that PRISM was more closely related to trauma-specic psychopathology than to nontrauma-specic psychopathology (discriminant validity) and sensitive to change. In summary, PRISM appears to be a valid tool for the assessment of trauma-related suffering and adds to multimethod approaches in trauma research.

Trauma-related assessment tools typically reect individual diagnostic entities such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) or other constructs such as posttraumatic cognitions (Foa, Tolin, Ehlers, Clark, & Orsillo, 1999). To our knowledge, no single measure assesses the perceived impact (rather than mere occurrence) of the consequences of a given traumatic experience in a comprehensive way allowing for consideration of all individually relevant dimensions (e.g., psychopathology, physical health, work situation, social circumstances). We assume that the construct of traumarelated suffering is best suited to reect the entirety of this subjective experience (impact). Trauma-related suffering results from a complex interaction between psychological, physical, and social sequelae of a traumatic event, including relevant aspects of the individual concerned (e.g., personality traits, value systems, social resources). The Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure (PRISM) has been developed as a visualization tool to measure the burden of suffering and has successfully been

validated in various conditions such as chronic illness (i.e., Buchi et al., 2002) and pain (i.e., Streffer, B chi, M rgeli, u o Galli, & Ettlin, 2009). As part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of brief eclectic psychotherapy (BEP) for PTSD (Schnyder, M ller, Maercker, & Wittmann, 2011), u we performed a pilot study on the validity of PRISM as a measure of trauma-related suffering. Method Participants and Procedure The Ethics Committee of the Canton of Zurich approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The main inclusion criterion was a total score of at least 50 points on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1998), resulting in a current diagnosis of full or subsyndromal (Blanchard, Hickling, Taylor, & Loos, 1995) PTSD in relation to traumatic exposure at least 6 months prior to entering the RCT. Fluency in German and age between 18 and 70 years were additional inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria were psychotic, bipolar, substance-related, or severe personality disorders; current severe depression; severe cognitive impairment or a history of organic mental disorder; ongoing traumatization; prominent current suicidal or homicidal ideation, unstable psychotropic medication, and asylum-seeking status. Thirty patients fullled the inclusion criteria and were randomly assigned to either 16 sessions of BEP (n = 16) or a minimal attention control condition (n = 14). As the 94

This study was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (3200B0-102204.03), Olga Mayensch Foundation, Hermann Klaus Foundation, and the Zurich University Jubil umsspende. a Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lutz Wittmann, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Zurich, Culmannstrasse 8, 8091 Zurich, Switzerland. E-mail: lutz.wittmann@usz.ch Copyright C 2012 International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. View this article online at wileyonlinelibrary.com DOI: 10.1002/jts.20710

Assessment of Suffering After Trauma

95

and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983; range = 021). For the assessment of psychopathological symptom load during the last 7 days, we used the validated German 9-item short version SCL-K-9 (Klaghofer & Br hler, 2001) of the Symptom Checklist-90-R, the toa tal score or global severity index (GSI; range = 036) of which proved to correlate almost perfectly (r = .93) with the GSI of the SCL-90-R in a representative sample of the German general population (Klaghofer & Br hler, 2001). a Trauma history was assessed using Part A of the PDS and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 2003).

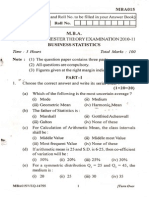

Figure 1. PRISM (Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure).

Statistical Analyses control group was offered identical treatment after 16 weeks in the control condition, data from both groups were pooled together for the current analyses based on pretreatment, posttreatment, and 6-month follow-up assessments. Additionally, patients completed PRISM, PDS, and SCL prior to therapy sessions 7 and 13. One patient who refused treatment after the control condition was excluded from the present analyses, resulting in a total sample size of 29. Measures PRISM (Buchi et al., 2002) consists of a white metal board measuring 210 297 mm (A4 format) with a xed yellow disk (7-cm diameter) at the bottom right-hand corner, representing the patients self (Figure 1). Patients are given a red 5-cm-diameter magnetic disk and instructed to imagine that the disk represents their illness (in this study: trauma). They are asked to place this red disk on the metal board after receiving the following instruction: Where would you put the illness (trauma) disk to illustrate its place in your life right now? The main quantitative measure derived from PRISM is the self-illness separation, or in this study, self-trauma separation (STS), i.e., the distance between the centers of the trauma and the self disks ranging from 0 to 270 mm with higher STS distances reecting lesser suffering. PRISMs convergent and discriminant validity have been demonstrated by the presence and absence of correlations between specic physical and psychological variables, different proles of these correlations in different illnesses, and changes in PRISM scores accompanying changes in physical state (Buchi et al., 2002). Qualitative analyses of the individual meaning of the distance between self and illness detected three main aspects: (a) loss of control and personal autonomy, (b) loss of social or personal roles, and (c) increase in symptoms (Buchi et al., 2002). PTSD symptoms during the last month were assessed with the CAPS (Blake et al., 1998; range = 0136) and Part B of the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, Cashman, Jaycox, & Perry, 1997; range = 051). Current Axis I and II psychopathology was measured using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSMIV (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1996; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). Depression during the previous few days was assessed applying the Hospital Anxiety

Copyright

C

Statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 19. Effects of the factors time and PTSD diagnostic status on PRISM STS were tested by one-factorial general linear models (GLM) or t tests. Due to the limited sample size, differences between the three diagnostic groups were quantied by effect sizes (Cohens d) rather than calculating post hoc comparisons. Correlations assessed PRISMs test-retest reliability from posttherapy to follow-up assessment and its association with measures of psychopathology (convergent validity) and trauma history (discriminant validity). If PRSIM STS reects trauma-related suffering which we assume to result from the interaction of trauma sequelae with characteristics of the individual concerned it should not be associated with the mere occurrence of traumatic events. To further examine PRISMs discriminant validity and sensitivity to change, changes over time in PRISM STS and trauma-specic and nontraumaspecic markers were shown at the available assessment time points. The values of these four measures were transformed into T scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Results Descriptive data were obtained at pretreatment assessment. Thirteen participants (45%) were women; mean age of the sample was 43.0 (SD = 14.0) years. Eighteen participants (62%) were of Swiss nationality, 11 (38%) were on stable psychotropic medication. Index traumatic events included serious accidents (n = 13), violent sexual or nonsexual assaults (n = 8), and other traumatic events (n = 8). The median of time lapsed since the index trauma was 1.8 years (range = 0.550.5). Nineteen patients (66%) were diagnosed with full PTSD, the remaining 10 (35%) with subsyndromal PTSD. Mean pretreatment CAPS score was 71.6 (SD = 17.7). Nineteen patients (66%) received a comorbid Axis I diagnosis, with anxiety (41%) and mood (38%) disorders being the most prominent. Seven of them received an additional comorbid Axis II diagnosis. PRISM STS mean scores were 35.2 (SD = 43.0, N = 29) at pretreatment, 83.9 (SD = 82.8, n = 27) at posttreatment, and 95.4 (SD = 84.8, n = 24) at follow- up assessment. A GLM detected a signicant effect of time, F(1.69, 24) = 14.37, p < .001, partial 2 = .39. Subsequent paired t tests

Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2012, 25, 9497

2012 International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

96

Wittmann et al.

Table 1 Correlations Between PRISM STS and Measures of Psychopathology and Traumatization Pretreatment Variable CAPS total score PDS total score HADS-depression score SCL-9 GSI CTQ total score Number of trauma types n 29 25 25 25 27 29 r .53 .49 .55 .38 .18 .20 n 27 25 25 25 Posttreatment r .74 .77 .69 .68 n 24 22 22 23 Follow-Up r .76 .81 .81 .60

Note. PRISM = Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure; STS = self-trauma separation; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SCL-9 GSI = Global Severity Index of Symptom Check-List-Short Version 9; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

p < .05. p < .01. p < .001.

indicated a signicant decline from pre- to posttreatment assessment, t(26) = 3.78, p < .001, d = 0.7, which was maintained during the follow-up interval, t(23) = 0.42, p = .679, d = 0.1. Test-retest reliability from posttherapy to follow-up assessment was r = .85 (p < .001, n = 24). In the next step, association of PRISM STS and diagnostic status was analyzed. A t test indicated signicant STS differences, t(27) = 2.27, p = .031, d = 0.8, between patients with full (M = 22.9, SD = 34.3, n = 19) and subsyndromal (M = 58.5, SD = 50.0, n = 10) PTSD at pretreatment assessment. All participants had at least a subsyndromal PTSD diagnosis at pretreatment assessment. At posttreatment, a signicant main effect for diagnostic status, F(2, 27) = 15.44, p < .001, partial 2 = .56, with respect to PRISM STS was detected (full PTSD: M = 36.1, SD = 37.8, n = 14; subsyndromal PTSD: M = 71.0, SD = 56.4, n = 5; no PTSD diagnosis: M = 175.6, SD = 81.6, n = 8). Effect sizes indicated substantial differences for STS between subjects with no versus subsyndromal PTSD (d = 1.5), subsyndromal versus full PTSD (d = 0.7), and no versus full PTSD (d = 2.2). Similarly, a signicant main effect for diagnostic status, F(2, 24) = 7.75, p = .003, partial 2 = .43, with respect to PRISM STS was detected at follow-up assessment (full PTSD: M = 37.2, SD = 30.1, n = 9; subsyndromal PTSD: M = 95.0, SD = 80.7, n = 8; no PTSD diagnosis: M = 170.7, SD = 83.9, n = 7). Effect sizes reecting differences in STS between diagnostic groups were d = 0.9 for no versus subsyndromal PTSD, d = 1.0 for subsyndromal versus full PTSD, and d = 2.1 for no versus full PTSD. Convergent validity was assessed calculating correlations between PRISM STS and measures of psychopathology. Strong correlations between PRISM STS and measures of PTSD severity and depression were observed at all time points (Table 1). As for SCL GSI, correlations were in the moderate range at pretreatment, and strong at later assessment time points. Finally, discriminant validity and sensitivity to change were assessed. Childhood traumatic experiences and number of trauma types (lifetime) were not signicantly related to PRISM STS (Table 1). Figure 2 illustrates the

time course of T scores of PRISM STS, PDS, SCL-9 GSI, as well as HADS-depression subscale over time. PRISM STS and PDS T scores appeared to be closely associated from pre- to posttreatment, with only a minor difference at follow-up assessment. At the same time, their time course apparently differed from that of the HADS-depression and SCL-9 GSI, which appear to be closely associated with one another. Discussion This study applied a validated instrument for the assessment of suffering in chronic illness, adapted for use in trauma research, in a sample of severely traumatized patients undergoing trauma-focused psychotherapy. As expected, trauma-related suffering signicantly declined after psychotherapy for PTSD. Test-retest reliability during the follow-up interval was high. PRISM discriminated well between subjects with full, subsyndromal, and no PTSD diagnosis and showed strong correlations with measures of trauma-specic and nonspecic psychopathology (convergent validity). We assume that the somewhat less pronounced correlations at pretreatment assessment can be explained by the restricted range of CAPS scores at baseline. The absence of a signicant relationship between PRISM and trauma history and illustration of PRISM STS time course combined with measures of psychopathology indicate PRISMs discriminant validity as a measure of trauma-related suffering as well as sensitivity to change. This study has a number of limitations that need to be considered. First, the small sample size raises questions regarding the representativeness of our results. Furthermore, a replication study should include patients reporting Type II traumatic events (Terr, 1991), collect qualitative data on how trauma survivors interpret the PRISM instructions, and compare PRISM STS to putatively related constructs such as centrality (Berntsen & Rubin, 2006). Notwithstanding these limitations, we believe that PRISM could make a valuable contribution to the eld of traumatic stress. Given that the alleviation of suffering is one of the main goals of medicine (Cassell, 1982), the signicance of its

Copyright

2012 International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2012, 25, 9497

Assessment of Suffering After Trauma

97

Figure 2. Development of T scores of PRISM (Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure) and psychopathological measures over time. STS = self-trauma separation; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PDS = Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; SCL-9 GSI = Global Severity Index of Symptom Check-List-Short Version 9; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

scope and value in assessing trauma survivors, in addition to existing trauma-related constructs, seems evident.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., . . ., Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 169190. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2006). The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into ones identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 44, 219231. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009 Blake, D. D., Weathers, F. W., Nagy, L. M., Kapoulek, D. G., Charney, D. S., & Keane, T. M. (1998). Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV. Boston, MA: National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Blanchard, E. B., Hickling, E. J., Taylor, A. E., & Loos, W. (1995). Psychiatric morbidity associated with motor vehicle accidents. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183, 495504. doi:10.1097/00005053199508000-00001 Buchi, S., Buddeberg, C., Klaghofer, R., Russi, E. W., Brandli, O., Schlosser, C., . . ., Sensky, T. (2002). Preliminary validation of PRISM (Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure)a brief method to assess suffering. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 71, 333341. doi:10.1159/000065994 Cassell, E. J. (1982). The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. New England Journal of Medicine, 306, 639645. doi:10.1056/NEJM198203183061104

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (1996). Users guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 1 Disordersresearch version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatriy Press. First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W. (1996). Users guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press. Foa, E. B., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L., & Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment, 9, 445451. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.445 Foa, E. B., Tolin, D. F., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., & Orsillo, S. M. (1999). The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 11, 303314. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.303 Klaghofer, R., & Br hler, E. (2001). Konstruktion und teststatistische a pr fung einer kurzform der SCL-90-R [Consturction and psychou metric evaluation of a short version of the SCL-90-R]. Zeitschrift f r klinische Psychologie, Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 49, 115 u 124. Schnyder, U., M ller, J., Maercker, A., & Wittmann, L. (2011). Brief u eclectic psychotherapy for PTSDa randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72, 564566. doi:10.4088/JCP.10l06247blu Streffer, M., B chi, S., M rgeli, H., Galli, U., & Ettlin, D. (2009). PRISM u o (Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure)a novel visual instrument to assess pain and suffering in orofacial patients. Journal of Orofaccial Pain, 23, 140146. Terr, L. C. (1991). Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 1020. Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67, 361 370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Copyright

2012 International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2012, 25, 9497

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- DBT-SP Skills Training Manual v3 4Document154 pagesDBT-SP Skills Training Manual v3 4Tatiana Buianina100% (3)

- Damasio Cortical EmotionDocument10 pagesDamasio Cortical EmotionTatiana BuianinaNo ratings yet

- Marsh Tversky Hutson EyewitnessDocument31 pagesMarsh Tversky Hutson EyewitnessTatiana BuianinaNo ratings yet

- The Microskills ApproachDocument2 pagesThe Microskills ApproachTatiana Buianina0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Statistical Analysis of DefectsDocument28 pagesStatistical Analysis of Defectsapi-295532576No ratings yet

- Cracking Phenomena IV PDFDocument502 pagesCracking Phenomena IV PDFNormix Flowers100% (1)

- MBA-015 Business StatisticsDocument7 pagesMBA-015 Business StatisticsA170690No ratings yet

- Chapter 5: Managing Investment RiskDocument13 pagesChapter 5: Managing Investment RiskMayank GuptaNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia Stats v3Document37 pagesEncyclopedia Stats v3AmitNo ratings yet

- SPSS Training Program & Introduction To Statistical Testing: Variance and VariablesDocument13 pagesSPSS Training Program & Introduction To Statistical Testing: Variance and VariablesThu DangNo ratings yet

- Lending Policy of Nepal Bank by Nabina RegmiDocument45 pagesLending Policy of Nepal Bank by Nabina RegmiKaran Pandey50% (2)

- 1 Assignment - TIGER TOOLSDocument5 pages1 Assignment - TIGER TOOLSSneha MehtaNo ratings yet

- JMP Help 2Document4 pagesJMP Help 2handsomepeeyushNo ratings yet

- Iet 603 700 Forum 6Document5 pagesIet 603 700 Forum 6api-285292212No ratings yet

- Risk Chapter 2Document27 pagesRisk Chapter 2Wonde Biru100% (1)

- Global Variation in Grip Strength - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Normative DataDocument8 pagesGlobal Variation in Grip Strength - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Normative DataMárciaPereiraNo ratings yet

- Impact of Interest Rate Spread On Profitability of Commercial Banks in NepalDocument44 pagesImpact of Interest Rate Spread On Profitability of Commercial Banks in NepalSujan pokhrelNo ratings yet

- A Fictitious Six Sigma Green Belt Part IDocument19 pagesA Fictitious Six Sigma Green Belt Part IhalilpashaNo ratings yet

- Cusum Charts V-MaskDocument12 pagesCusum Charts V-MaskmathanrochNo ratings yet

- Lect-3-Risk and Return (Compatibility Mode)Document70 pagesLect-3-Risk and Return (Compatibility Mode)Poh Yih ChernNo ratings yet

- Estimating Population VarianceDocument26 pagesEstimating Population VarianceThesis Group- Coronado Reyes Zapata UST ChENo ratings yet

- Impact of Knowledge Management Processes On Organizational PerformanceDocument12 pagesImpact of Knowledge Management Processes On Organizational PerformanceAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Sample: Six Sigma Black Belt Project ReportDocument23 pagesSample: Six Sigma Black Belt Project ReportcharanNo ratings yet

- 3.software Quality AssuranceDocument22 pages3.software Quality AssurancearunlaldsNo ratings yet

- Data Handling and Parameter Estimation: Gürkan Sin Krist V. Gernaey Sebastiaan C.F. Meijer Juan A. BaezaDocument34 pagesData Handling and Parameter Estimation: Gürkan Sin Krist V. Gernaey Sebastiaan C.F. Meijer Juan A. BaezaKenn WahhNo ratings yet

- Hypothesis Testing in Concrete NptelDocument43 pagesHypothesis Testing in Concrete NptelN TAMIL SELVINo ratings yet

- Confidence IntervalsDocument6 pagesConfidence Intervalsandrew22No ratings yet

- End-to-End Deep Learning of Optical Fiber CommunicationDocument13 pagesEnd-to-End Deep Learning of Optical Fiber Communicationabul_1234No ratings yet

- ImutilsDocument51 pagesImutilsVaziel Ivans100% (1)

- Semester I - Paper II (2015 Admission) Ouantitave Techniques For Business Decisions - CompressedDocument166 pagesSemester I - Paper II (2015 Admission) Ouantitave Techniques For Business Decisions - Compressedakanchha kumariNo ratings yet

- MPH Entrance Examination With AnswersDocument42 pagesMPH Entrance Examination With Answersahmedhaji_sadik94% (87)

- Statistics and Probability: Random SampleDocument13 pagesStatistics and Probability: Random SampleClaire Balatucan100% (1)

- 2016 06 - Level - 1 - Mock114 - V2 - QnsDocument41 pages2016 06 - Level - 1 - Mock114 - V2 - QnshuiminleongNo ratings yet

- SLR NotesDocument96 pagesSLR NotesRafi DawarNo ratings yet