Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Africa Vs Caltex by HMM

Uploaded by

hash_tntOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Africa Vs Caltex by HMM

Uploaded by

hash_tntCopyright:

Available Formats

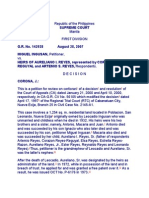

G.R. No.

L-12986

March 31, 1966

THE SPOUSES BERNABE AFRICA and SOLEDAD C. AFRICA, and the HEIRS OF DOMINGA ONG, petitioners-appellants, vs. CALTEX (PHIL.), INC., MATEO BOQUIREN and THE COURT OF APPEALS, respondents-appellees. Facts: In March 1948, in Rizal Avenue, Manila, a tank truck was hosing gasoline into the underground storage of Caltex. Apparently, a fire broke out from the gasoline station and the fire spread and burned several houses including the house of Africa. Allegedly, someone (a passerby) threw a cigarette while gasoline was being transferred which caused the fire. But there was no evidence presented to prove this theory and no other explanation can be had as to the real reason for the fire. Apparently also, Caltex and the branch owner (Boquiren) failed to install a concrete firewall to contain fire if in case one happens Issue: Whether Caltex should be held liable for the damages caused to appellants. Held: This question depends on whether the operator of the gasoline station was an independent contractor or an agent of Caltex. Under the license agreement the operator would pay Caltex the purely nominal sum of P1.00 for the use of the premises and all equipment therein. The operator could sell only Caltex products. Maintenance of the station and its equipment was subject to the approval, in other words control, of Caltex. The operator could not assign or transfer his rights as licensee without the consent of Caltex. Termination of the contract was a right granted only to Caltex but not to the operator. These provisions of the contract show that the operator was virtually an employee of the Caltex, not an independent contractor. Hence, Caltex should be liable for damages caused to appellants Caltex admits that it owned the gasoline station as well as the equipment therein, but claims that the business conducted at the service station in question was owned and operated by Boquiren. But Caltex did not present any contract with Boquiren that would reveal the nature of their relationship at the time of the fire. What was presented was a license agreement manifestly tailored for purposes of this case, since it was entered into shortly before the expiration of the one-year period it was intended to operate. This socalled license agreement was executed on November 29, 1948, but made effective as of January 1, 1948 so as to cover the date of the fire, namely, March 18, 1948. This retroactivity provision is quite significant, and gives rise to the conclusion that it was designed precisely to free Caltex from any responsibility with respect to the fire, as shown by the clause that Caltex "shall not be liable for any injury to person or property while in the property herein licensed, it being understood and agreed that LICENSEE (Boquiren) is not an employee, representative or agent of LICENSOR (Caltex)." But even if the license agreement were to govern, Boquiren can hardly be considered an independent contractor. Under that agreement Boquiren would pay Caltex the purely nominal sum of P1.00 for the use of the premises and all the equipment therein. He could sell only Caltex Products. Maintenance of the station and its equipment was subject to the approval, in other words control, of Caltex. Boquiren could not assign or transfer his rights as licensee without the consent of Caltex. The license agreement was supposed to be from January 1, 1948 to December 31, 1948, and thereafter until terminated by Caltex upon two days prior written notice. Caltex could at any time cancel and terminate the agreement in case Boquiren ceased to sell Caltex products, or did not conduct the business with due diligence, in the judgment of Caltex. Termination of the contract was therefore a right granted only to Caltex but not to Boquiren. These provisions of the contract show the extent of the control of Caltex over Boquiren. The control was such that the latter was virtually an employee of the former.

You might also like

- Sps. Africa DigestDocument2 pagesSps. Africa DigestJoseph MacalintalNo ratings yet

- Transpo Case DigestDocument24 pagesTranspo Case Digestblue_supeeNo ratings yet

- APL v. KlepperDocument3 pagesAPL v. KlepperJen T. TuazonNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs Acoje MiningDocument1 pageRepublic Vs Acoje MiningApril Gem BalucanagNo ratings yet

- Negado Vs MakabentaDocument1 pageNegado Vs MakabentaMark Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Victorias Milling v. CA G.R. No. 117356Document1 pageVictorias Milling v. CA G.R. No. 117356Pring SumNo ratings yet

- Torts Case Digest Damages 1st PartDocument50 pagesTorts Case Digest Damages 1st PartJanice DulotanNo ratings yet

- Insurance - Week 4Document8 pagesInsurance - Week 4Stephanie GriarNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction over property disputeDocument48 pagesJurisdiction over property disputeCharina BalunsoNo ratings yet

- Saludo Vs PNB - DIGESTDocument3 pagesSaludo Vs PNB - DIGESTI took her to my penthouse and i freaked itNo ratings yet

- Ago vs. CADocument3 pagesAgo vs. CAJan Carlo SanchezNo ratings yet

- TOCAO Vs CA PDFDocument2 pagesTOCAO Vs CA PDFPatricia SanchezNo ratings yet

- ImmunityDocument3 pagesImmunityEmiaj Francinne MendozaNo ratings yet

- 09 Roa, Jr. Vs CADocument17 pages09 Roa, Jr. Vs CAJanine RegaladoNo ratings yet

- Evidence Third SetDocument3 pagesEvidence Third SetKen ArnozaNo ratings yet

- Mineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA)Document4 pagesMineral Production Sharing Agreement (MPSA)teresaNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws CasesDocument36 pagesConflict of Laws CasesWillow SapphireNo ratings yet

- China Banking Corp. v. CoDocument6 pagesChina Banking Corp. v. CoRubyNo ratings yet

- Ancheta vs. Guersy-DalaygonDocument3 pagesAncheta vs. Guersy-DalaygonTrisha Faith Balido PagaraNo ratings yet

- Bus-Org Cases-31 To 40Document7 pagesBus-Org Cases-31 To 40Dashy CatsNo ratings yet

- Servando vs. Philippine Steam Navigation Co.Document10 pagesServando vs. Philippine Steam Navigation Co.poppo1960No ratings yet

- LRT Authority Liable for Passenger DeathDocument2 pagesLRT Authority Liable for Passenger DeathMhaliNo ratings yet

- G.R. 195229 Ara Tea Vs Comelec Full TextDocument16 pagesG.R. 195229 Ara Tea Vs Comelec Full TextDino Bernard LapitanNo ratings yet

- Far Eastern Company vs Lim Teck Suan Supreme Court RulingDocument1 pageFar Eastern Company vs Lim Teck Suan Supreme Court RulingJoseph Macalintal100% (1)

- Ingusan Vs Heirs of ReyesDocument11 pagesIngusan Vs Heirs of ReyesMark AnthonyNo ratings yet

- Case Digest PartnershipDocument12 pagesCase Digest Partnershipkingofhearts006No ratings yet

- PNB vs. Andrada Dispute Over Corporate Liability <40Document66 pagesPNB vs. Andrada Dispute Over Corporate Liability <40Ray LegaspiNo ratings yet

- Gargantos Vs YanonDocument1 pageGargantos Vs YanonjneNo ratings yet

- University of Immaculate Conepcion vs. NLRCDocument15 pagesUniversity of Immaculate Conepcion vs. NLRCMariam PetillaNo ratings yet

- 97 Phil 171Document9 pages97 Phil 171asnia07No ratings yet

- Yu v. NLRCDocument3 pagesYu v. NLRCBettina Rayos del SolNo ratings yet

- BF Corporation V Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesBF Corporation V Court of AppealsRich ReyesNo ratings yet

- Credit Transaction Case DigestDocument4 pagesCredit Transaction Case Digestantolin becerilNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules Punitive Damages are Taxable IncomeDocument5 pagesSupreme Court Rules Punitive Damages are Taxable IncomejNo ratings yet

- Gillaco v. Manila RailroadDocument4 pagesGillaco v. Manila RailroadHaniyyah FtmNo ratings yet

- Naguiat V CADocument3 pagesNaguiat V CADinnah Mae AlconeraNo ratings yet

- Camarines Norte vs. Gonzales DigestDocument4 pagesCamarines Norte vs. Gonzales DigestfreezoneNo ratings yet

- Raytheon v. Rouzie Forum Non Conveniens RulingDocument2 pagesRaytheon v. Rouzie Forum Non Conveniens RulingJoan PaynorNo ratings yet

- Imasen Philippine Manufacturing Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Ramonchito T. Alcon and Joann S. Papa, Respondents FactsDocument1 pageImasen Philippine Manufacturing Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Ramonchito T. Alcon and Joann S. Papa, Respondents FactsTiff DizonNo ratings yet

- Bagong Filipinas Overseas CorporationDocument1 pageBagong Filipinas Overseas CorporationRegina FordNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz Vs Northern Theatrical EnterpriseDocument2 pagesDela Cruz Vs Northern Theatrical EnterpriseRic Laurence SaysonNo ratings yet

- Naguiat vs Court of Appeals agency disputeDocument1 pageNaguiat vs Court of Appeals agency disputeLawrence RiodequeNo ratings yet

- Torts Cases 2Document32 pagesTorts Cases 2Janice DulotanNo ratings yet

- 39 Metrobank vs. CabilzoDocument3 pages39 Metrobank vs. CabilzoJanno SangalangNo ratings yet

- Agency DIgests Part IIDocument10 pagesAgency DIgests Part IIJolo GalpoNo ratings yet

- Prof. Joseph Emmanuel L. Angeles: University of The Philippines College of LawDocument17 pagesProf. Joseph Emmanuel L. Angeles: University of The Philippines College of Lawrgtan3No ratings yet

- PH Supreme Court upholds order for certification election between unionsDocument2 pagesPH Supreme Court upholds order for certification election between unionsJohn Rey Bantay RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Court Holds Real Estate Firm Jointly Liable for Fraud in Land Sale DealDocument5 pagesCourt Holds Real Estate Firm Jointly Liable for Fraud in Land Sale Dealsunsetsailor85No ratings yet

- Political Law - Territorial SovereigntyDocument4 pagesPolitical Law - Territorial SovereigntyMarie Mariñas-delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- EVIDENCE Maulini v. SerranoDocument13 pagesEVIDENCE Maulini v. SerranoBoysie Ceth GarvezNo ratings yet

- Aznar Brothers Vs AyingDocument3 pagesAznar Brothers Vs AyingRia Kriselle Francia PabaleNo ratings yet

- Villa V Garcia Boque (B. Obli of An Agent)Document1 pageVilla V Garcia Boque (B. Obli of An Agent)Anonymous mv3Y0KgNo ratings yet

- US V Kiene DOCTRINE: Where Nothing To The Contrary Appears, The Provisions of Article 1720 of The Civil CodeDocument1 pageUS V Kiene DOCTRINE: Where Nothing To The Contrary Appears, The Provisions of Article 1720 of The Civil CodeNN DDLNo ratings yet

- The Philippine Shipping Company Et. Al. v. Vergara G.R. No. L-1600, June 1, 1906 FactsDocument40 pagesThe Philippine Shipping Company Et. Al. v. Vergara G.R. No. L-1600, June 1, 1906 FactsHarry Dave Ocampo PagaoaNo ratings yet

- The Spouses Bernabe Africa and Soledad CDocument1 pageThe Spouses Bernabe Africa and Soledad CCher UyNo ratings yet

- Africa v. CaltexDocument3 pagesAfrica v. CaltexAndres VillaruelNo ratings yet

- American Home Assurance Company vs. Tantuco Enterprises, Inc., (G.R. No. 138941. October 8, 2001) FactsDocument2 pagesAmerican Home Assurance Company vs. Tantuco Enterprises, Inc., (G.R. No. 138941. October 8, 2001) FactsPatricia Anne GonzalesNo ratings yet

- AMERICAN HOME ASSURANCE COMPANY, Petitioner, vs. TANTUCO ENTERPRISES, INC., RespondentDocument6 pagesAMERICAN HOME ASSURANCE COMPANY, Petitioner, vs. TANTUCO ENTERPRISES, INC., RespondentMichael John CaloNo ratings yet

- Sps. Africa, Pearl Is., Switzerland DIGESTDocument4 pagesSps. Africa, Pearl Is., Switzerland DIGESTJoseph MacalintalNo ratings yet

- American Home Assurance v. Tantuco Ent. (366 SCRA 740)Document7 pagesAmerican Home Assurance v. Tantuco Ent. (366 SCRA 740)Jessie BarredaNo ratings yet

- Sevilla Vs CADocument8 pagesSevilla Vs CAhash_tntNo ratings yet

- LKJKJLKDocument2 pagesLKJKJLKhash_tntNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of NonDocument11 pagesThe Effectiveness of Nonhash_tnt0% (1)

- Development Bank Fails to Collect Unpaid Loan Balance Due to Lack of Check DeliveryDocument2 pagesDevelopment Bank Fails to Collect Unpaid Loan Balance Due to Lack of Check Deliveryhash_tntNo ratings yet

- Functions of IpoDocument3 pagesFunctions of Ipohash_tntNo ratings yet

- Tañada V AngaraDocument3 pagesTañada V AngaraSui100% (3)

- McDonald's vs. Big Mak Burger trademark disputeDocument4 pagesMcDonald's vs. Big Mak Burger trademark disputehash_tntNo ratings yet

- Kho Vs CADocument1 pageKho Vs CAhash_tntNo ratings yet

- Jang Geun Suk's Goodbye SongDocument13 pagesJang Geun Suk's Goodbye SongshinomeiNo ratings yet

- DBP VscaDocument1 pageDBP Vscahash_tntNo ratings yet

- DBP VscaDocument1 pageDBP Vscahash_tntNo ratings yet

- Roxas VS CaDocument2 pagesRoxas VS Cahash_tnt67% (3)

- 13 Daftar PustakaDocument2 pages13 Daftar PustakaDjauhari NoorNo ratings yet

- KL Wellness City LIvewell 360 2023Document32 pagesKL Wellness City LIvewell 360 2023tan sietingNo ratings yet

- Maths Lit 2014 ExamplarDocument17 pagesMaths Lit 2014 ExamplarAnymore Ndlovu0% (1)

- Chi Square LessonDocument11 pagesChi Square LessonKaia HamadaNo ratings yet

- Uniform Bonding Code (Part 2)Document18 pagesUniform Bonding Code (Part 2)Paschal James BloiseNo ratings yet

- Master StationDocument138 pagesMaster StationWilmer Quishpe AndradeNo ratings yet

- Final Biomechanics of Edentulous StateDocument114 pagesFinal Biomechanics of Edentulous StateSnigdha SahaNo ratings yet

- OPIM101 4 UpdatedDocument61 pagesOPIM101 4 UpdatedJia YiNo ratings yet

- MMDS Indoor/Outdoor Transmitter Manual: Chengdu Tengyue Electronics Co., LTDDocument6 pagesMMDS Indoor/Outdoor Transmitter Manual: Chengdu Tengyue Electronics Co., LTDHenry Jose OlavarrietaNo ratings yet

- A Research About The Canteen SatisfactioDocument50 pagesA Research About The Canteen SatisfactioJakeny Pearl Sibugan VaronaNo ratings yet

- TicketDocument2 pagesTicketbikram kumarNo ratings yet

- SIWES Report Example For Civil Engineering StudentDocument46 pagesSIWES Report Example For Civil Engineering Studentolayinkar30No ratings yet

- Hindustan Coca ColaDocument63 pagesHindustan Coca ColaAksMastNo ratings yet

- Air Cycle Refrigeration:-Bell - Coleman CycleDocument21 pagesAir Cycle Refrigeration:-Bell - Coleman CycleSuraj Kumar100% (1)

- Lirik and Chord LaguDocument5 pagesLirik and Chord LaguRyan D'Stranger UchihaNo ratings yet

- Iqvia PDFDocument1 pageIqvia PDFSaksham DabasNo ratings yet

- Machine Design - LESSON 4. DESIGN FOR COMBINED LOADING & THEORIES OF FAILUREDocument5 pagesMachine Design - LESSON 4. DESIGN FOR COMBINED LOADING & THEORIES OF FAILURE9965399367No ratings yet

- 2.4 Adams Equity TheoryDocument1 page2.4 Adams Equity TheoryLoraineNo ratings yet

- Alexander Lee ResumeDocument2 pagesAlexander Lee Resumeapi-352375940No ratings yet

- Successful Organizational Change FactorsDocument13 pagesSuccessful Organizational Change FactorsKenneth WhitfieldNo ratings yet

- Verifyning GC MethodDocument3 pagesVerifyning GC MethodHristova HristovaNo ratings yet

- PaySlip ProjectDocument2 pagesPaySlip Projectharishgogula100% (1)

- Military Railway Unit Histories Held at MHIDocument6 pagesMilitary Railway Unit Histories Held at MHINancyNo ratings yet

- Siyaram S AR 18-19 With Notice CompressedDocument128 pagesSiyaram S AR 18-19 With Notice Compressedkhushboo rajputNo ratings yet

- Triblender Wet Savoury F3218Document32 pagesTriblender Wet Savoury F3218danielagomezga_45545100% (1)

- NH School Employee Criminal Record Check FormDocument2 pagesNH School Employee Criminal Record Check FormEmily LescatreNo ratings yet

- Sample Contract Rates MerchantDocument2 pagesSample Contract Rates MerchantAlan BimantaraNo ratings yet

- The Causes of Cyber Crime PDFDocument3 pagesThe Causes of Cyber Crime PDFInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Knowledge and SkillDocument2 pagesDifference Between Knowledge and SkilljmNo ratings yet

- Cycles in Nature: Understanding Biogeochemical CyclesDocument17 pagesCycles in Nature: Understanding Biogeochemical CyclesRatay EvelynNo ratings yet

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansFrom EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeNo ratings yet

- Hell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryFrom EverandHell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America's Second SlaveryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedFrom Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (109)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (33)

- The Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveFrom EverandThe Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (365)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1143)

- Broken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.From EverandBroken: The most shocking childhood story ever told. An inspirational author who survived it.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (43)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- If You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodFrom EverandIf You Tell: A True Story of Murder, Family Secrets, and the Unbreakable Bond of SisterhoodRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1788)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (327)

- The Girls Are Gone: The True Story of Two Sisters Who Vanished, the Father Who Kept Searching, and the Adults Who Conspired to Keep the Truth HiddenFrom EverandThe Girls Are Gone: The True Story of Two Sisters Who Vanished, the Father Who Kept Searching, and the Adults Who Conspired to Keep the Truth HiddenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (36)

- Double Lives: True Tales of the Criminals Next DoorFrom EverandDouble Lives: True Tales of the Criminals Next DoorRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassFrom EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (24)

- The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchFrom EverandThe Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIFrom EverandHearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Hey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel MarketingFrom EverandHey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel MarketingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (102)

- Dark Psychology: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Manipulation Using Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Mind Control, Subliminal Persuasion, Hypnosis, and Speed Reading Techniques.From EverandDark Psychology: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Manipulation Using Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Mind Control, Subliminal Persuasion, Hypnosis, and Speed Reading Techniques.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (88)

- His Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsFrom EverandHis Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (100)

- The Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalFrom EverandThe Bigamist: The True Story of a Husband's Ultimate BetrayalRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (103)

- Perfect Murder, Perfect Town: The Uncensored Story of the JonBenet Murder and the Grand Jury's Search for the TruthFrom EverandPerfect Murder, Perfect Town: The Uncensored Story of the JonBenet Murder and the Grand Jury's Search for the TruthRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (68)