Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nego Case Doctrines

Uploaded by

Stephano HawkingOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nego Case Doctrines

Uploaded by

Stephano HawkingCopyright:

Available Formats

22. PNB v. CA MERCANTILE LAW; CENTRAL BANK; CIRCULAR NO.

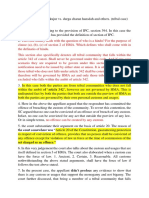

416; 12% RATE SPECIFIED THEREIN REFERS TO LOAN OR FORBEARANCE OF MONEY, GOODS OR CREDIT. The rate 12% interest referred to in Cir. 416 applies only to: "[L]oan or forbearance of money, or to cases where money is transferred from one person to another and the obligation to return the same or a portion thereof is adjudged. Any other monetary judgment which does not involve or which has nothing to do with loans or forbearance of any money, goods or credit does not fall within its coverage for such imposition is not within the ambit of the authority granted to the Central Bank. When an obligation not constituting a loan or forbearance of money is breached then an interest on the amount of damages awarded may be imposed at the discretion of the court at the rate of 6% per annum in accordance with Art. 2209 of the Civil Code. Indeed, the monetary judgment in favor of private respondent does not involve a loan or forbearance of money, hence the proper imposable rate of interest is six (6%) per cent." 22. montinola v. pnb 1. NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENT; MATERIAL ALTERATION WHICH DISCHARGES THE INSTRUMENT. On May 2, 1942, L in his capacity as Provincial Treasurer of Misamis Oriental as drawer, issued a check to R in the sum of P100,000, on the Philippines National Bank as drawee. R sold P30,000 of the check to m for P90,000 Japanese Military notes, of which only P45,000 was paid by M. The writing made by R at the back of the check was to the effect that he was assigning only P30,000 of the value of the document with an instruction to the bank to pay P30,000 to m and to deposit the balance to R's credit. This writing was, however, mysteriously obliterated and in its place, a supposed indorsement appearing on the back of the check was made. At the time of the transfer of this check to M about the last days of December, 1944 or the first days of January, 1845, the check was long overdue by about 2-1/2 years. In August, 1947, M instituted an action against the Philippine National Bank and the Provincial Treasurer of Misamis Oriental to collect the sum of P100,000, the amount of the aforesaid check. There now appears on the face of said check the words in parenthesis "Agent, Phil. National Bank" under the signature of L purportedly showing that L issued the check as agent of the Philippine National Bank. Held: The words "Agent, Phil. National Bank" now appearing on the face of the check were added or placed in the instrument after it was issued by the Provincial Treasurer L to R. The check was issued by only as Provincial Treasurer and as an official of the Government, which was under obligation to provide the USAFE with advance funds, and not as agent of the bank, which had no such obligation. The addition of those words was made after the check had been transferred by R to M. The insertion of the words "Agent, Phil. National Bank," which converts the bank from a mere drawee to a drawer and therefore changes its liability, constitutes a material alteration of the instrument without the consent of the parties liable thereon, and so discharges the instrument. 2. ID.; INDORSEMENT OF PART OF AMOUNT PAYABLE, IS NOT NEGOTIATION OF INSTRUMENT BUT MAY BE REGARDED AS MERE ASSIGNMENT. Where the indorsement of a check is only for a part of the amount payable, it is not legally negotiated within the meaning of section 32 of the Negotiable Instruments Law which provides that "the indorsement must be an indorsement of the entire instrument. An indorsement which purports to transfer to the indorse a part only of the amount payable

does not operate as a negotiation of the instrument." M may, therefore, not be regarded as an indorse. At most he may be regarded as a mere assignee of the P30,000 sold to him by R, in which case, as such Provincial Treasurer of Misamis Oriental against R. 3. ID.; HOLDER IN DUE COURSE; HOLDER WHO HAS TAKEN THE INSTRUMENT AFTER IT WAS LONG OVERDUE; ASSIGNEE IS NOT A PAYEE. Neither can M de considered as a holder in due course because section 52 of the Negotiable Instruments Law defines a holder in due course as a holder who taken the instrument under certain conditions, one of which is that he became the holder before it was overdue. When M received the check, it was long overdue. And, M is not even a holder because section 191 of the same law defines holder as the payee or indorse of a bill or note and m is not a payee. Neither is he an indorse, for being only indorse he is considered merely as an assignee. 4. ID.; INSTRUMENT ISSUED TO DISTRIBUTION OFFICER OF USAFE, WHO HAS NO RIGHT TO INDORSE IT PERSONALLY. Where an instrument was issued to R not as a person but as the disbursing officer of the USAFE, he has no right to indorse the instrument personally and if he does, the negotiation constitutes a breach of trust, and he transfers nothing to the indorse. 5. QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS; DISCREPANCIES BETWEEN PHOTOSTATIC COPY TAKEN BEFORE TEARING AND BURNING OF CHECK AND PRESENT CONDITION THEREOF SHOW WORDS IN QUESTION WERE INSERTED AFTER SAID TEARING AND BURNING. Recovery on a check, Exhibit A, depended on the presence of the words "Agent, Phil. National Bank" under the signature of L, at time Exhibit A was drawn. But the photostatic copy, Exhibit B, admittedly taken before Exhibit A was burned and torn, showed marked discrepancies between Exhibits A and B as to the position of the words in question in relation to the words "Provincial Treasurer". Held: The inference is plain that the words "Agent, Phil. National Bank" were inserted after the check was burned and torn.

23. Sadaya v. Sevilla 1. GUARANTY; RIGHT OF SOLIDARY ACCOMMODATION MAKER. A solidary accommodation maker-who made payment has the right to contribution, from his co-accommodation maker, in the absence of agreement to the contrary between them, and subject to conditions imposed by law. (Art. 2073, New Civil Code.) 2. ID.; ID.; REQUISITES WHEN DEMAND IS MADE ON A CO-GUARANTOR. (1) A joint and several accommodation maker of a negotiable promissory note may demand from the principal debtor reimbursement for the amount that he paid to the payee; (2) a joint and several accommodation maker who pays on the said promissory note may directly demand reimbursement from his co-accommodation maker without first directing his action against the principal debtor provided that (a) he made the payment by virtue of a judicial demand, or (b) the principal debtor is insolvent.

3. ID.; VOLUNTARY PAYMENT BY A CO-ACCOMMODATION MAKER WITHOUT PREVIOUS JUDICIAL DEMAND AND WHEN THE PRINCIPAL DEBTOR IS NOT INSOLVENT; EFFECT. Where a coaccommodation maker paid voluntarily the outstanding balance of the account of the principal debtor without previous judicial demand and when the principal debtor is not insolvent, he cannot, as a matter of right, demand from his co- accommodation maker of the share which is proportionately owing him. 24. crisologo-jose v. CA

1. COMMERCIAL LAW; NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW; ACCOMMODATION PARTY; REQUISITES THEREOF, CITED; THAT ACCOMMODATION PARTY FAILED TO RECEIVE ANY VALUABLE CONSIDERATION WHEN HE EXECUTED INSTRUMENT, NOT A VALID DEFENSE. To be considered an accommodation party, a person must (1) be a party to the instrument, signing as maker, drawer, acceptor, or indorser, (2) not receive value therefor, and (3) sign for the purpose of lending his name for the credit of some other person. Based on the foregoing requisites, it is not a valid defense that the accommodation party did not receive any valuable consideration when he executed the instrument. 2. ID.; ID.; ID.; LIABLE TO A HOLDER FOR VALUE. From the standpoint of contract law, he differs from the ordinary concept of a debtor therein in the sense that he has not received any valuable consideration for the instrument he signs. Nevertheless, he is liable to a holder for value as if the contract was not for accommodation, in whatever capacity such accommodation party signed the instrument, whether primarily or secondarily. 3. ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; DOES NOT INCLUDE NOR APPLY TO CORPORATIONS, REASON. Section 29 of the Negotiable Instruments Law which holds an accommodation party liable on the instrument to a holder for value, although such holder at the time of taking the instrument knew him to be only an accommodation party, does not include nor apply to corporations which are accommodation parties. This is because the issue or indorsement of negotiable paper by a corporation without consideration and for the accommodation of another is ultra vires. Hence, one who has taken the instrument with knowledge of the accommodation nature thereof cannot recover against a corporation where it is only an accommodation party. If the form of the instrument, or the nature of the transaction, is such as to charge the indorsee with knowledge that the issue or indorsement of the instrument by the corporation is for the accommodation of another, he cannot recover against the corporation thereon. 4. ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; EXCEPTION. By way of exception, an officer or agent of a corporation shall have the power to execute or indorse a negotiable paper in the name of the corporation for the accommodation of a third person only if specifically authorized to do so. 5. ID.; ID.; ID.; CORPORATE OFFICERS HAVE NO POWER TO EXECUTE FOR MERE ACCOMMODATION A NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENT OF THE CORPORATION FOR THEIR INDIVIDUAL DEBTS OR TRANSACTIONS IN WHICH THEY ARE PERSONALLY LIABLE. Corporate officers, such as the

president and vice-president, have no power to execute for mere accommodation a negotiable instrument of the corporation for their individual debts or transactions arising from or in relation to matters in which the corporation has no legitimate concern. Since such accommodation paper cannot thus be enforced against the corporation, especially since it is not involved in any aspect of the corporate business or operations, the inescapable conclusion in law and in logic is that the signatories thereof shall be personally liable therefor, as well as the consequences arising from their acts in connection therewith. 6. ID.; ID.; ID.; A CO-SURETY FOR ACCOMMODATED PARTY WITH WHOM HE AND HIS COSIGNATORY ASSUME SOLIDARY LIABILITY EX-LEGE FOR THE DEBT INVOLVED. Respondent Santos is an accommodation party and is, therefore, liable for the value of the check. The fact that he was only a co-signatory does not detract from his personal liability. A co-maker or co-drawer under the circumstances in this case is as much an accommodation party as the other co-signatory or, for that matter, as a lone signatory in an accommodation instrument. Under the doctrine in Philippine Bank of Commerce vs. Aruego, supra, he is in effect a co-surety for the accommodated party with whom he and his co-signatory, as the other co-surety, assume solidary liability ex lege for the debt involved. With the dishonor of the check, there was created a debtor-creditor relationship, as between Atty. Benares and respondent Santos, on the one hand, and petitioner, on the other. This circumstance enables respondent Santos to resort to an action of consignation where his tender of payment had been refused by petitioner.

25. stelco marketing v. ca 1. NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW; ACCOMMODATION PARTY; LIABLE TO A HOLDER FOR VALUE. STELCO evidently places much reliance on the pronouncement of the Regional Trial Court in Criminal Case No. 66571, that the acquittal of the two (2) accused (Limson and Torres) did not operate "to release Steelweld Corporation from its liability under Sec. 29 of the Negotiable Instruments Law for having issued (the check) for the accommodation of Romeo Lim." The cited provision reads as follows: "SECTION 29. Liability of accommodation party. An accommodation party is one who has signed the instrument as maker, drawer, acceptor, or indorser, without receiving value therefor, and for the purpose of lending his name to some other person. Such a person is liable on the instrument to a holder for value, notwithstanding such holder, at the time of taking the instrument, knew him to be only an accommodation party." It is noteworthy that the Trial Court's pronouncement containing reference to said Section 29 did not specify to whom STEELWELD, as accommodation party, is supposed to be liable; and certain it is that neither said pronouncement nor any other part of the judgment of acquittal declared it liable to STELCO. To be sure, as regards an accommodation party (such as STEELWELD), lack of notice of any infirmity in the instrument or defect in title of the persons negotiating it, has no application. This is because Section 29 of the law above quoted preserves the right of recourse of a "holder for value" against the accommodation party notwithstanding that "such holder, at the time of taking the instrument, knew him to be only an accommodation party" [Prudential Bank and Trust Co, v. Ramesh Trading Co. C.A. 32908-R, September 10, 1964].

2. ID.; ID.; HOLDER IN DUE COURSE; DEFINED. "A holder in due course," says the law, [SEC. 52, Negotiable Instruments Law, Act No. 2031] "is a holder who has taken the instrument under the following conditions: (a) That it is complete and regular upon its face; (b) That he became the holder of it before it was overdue, and without notice that it had been previously dishonored, if such was the fact; (c) That he took it in good faith and for value; (d) That at the time it was negotiated to him, he had no notice of any infirmity in the instrument or defect in the title of the persons negotiating it." 3. ID.; ID.; EFFECTS OF POSSESSION OF NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENT AFTER PRESENTMENT AND DISHONOR, OR PAYMENT. The record does show that after the check had been deposited and dishonored, STELCO came into possession of it in some way, and was able, several years after the dishonor of the check, to give it in evidence at the trial of the civil case it had instituted against the drawers of the check (Limson and Torres) and RLY. But, as already pointed out, possession of a negotiable instrument after presentment and dishonor, or payment, is utterly inconsequential; it does not make the possessor a holder for value within the meaning of the law; it gives rise to no liability on the part of the maker or drawer and indorsers

26. travel-on v. CA 1. COMMERCIAL LAW; NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW; PRESUMPTION OF CONSIDERATION; RULE. It is important to stress that a check which is regular on its face is deemed prima facie to have been issued for a valuable consideration and every person whose signature appears thereon is deemed to have become a party thereto for value. Thus, the mere introduction of the instrument sued on in evidence prima facie entitles the plaintiff to recovery. Further, the rule is quite settled that a negotiable instrument is presumed to have been given or indorsed for a sufficient consideration unless otherwise contradicted and overcome by other competent evidence. 2. ID.; ID.; ID.; BURDEN OF PROOF TO REBUT THEREOF; LIES WITH THE DRAWER; CASE AT BAR. In the case at bar, the Court of Appeals, contrary to these established rules, placed the burden of proving the existence of valuable consideration upon petitioner. This cannot be countenanced; it was up to private respondent to show that he had indeed issued the checks without sufficient consideration. The Court considers that private respondent was unable to rebut satisfactorily this legal presumption. It must also be noted that those checks were issued immediately after a letter demanding payment had been sent to private respondent by petitioner Travel-On. 3. ID.; ID.; ACCOMMODATION TRANSACTION; NOT ESTABLISHED IN CASE AT BAR; REASONS THEREFOR. We are unable to accept the Court of Appeals' conclusion that the checks here involved were issued for "accommodation" and that accordingly private respondent maker of those checks was not liable thereon to petitioner payee of those checks. In the first place, while the Negotiable Instruments Law does refer to accommodation transactions, no such transaction was here shown. In accommodation transactions recognized by the Negotiable Instruments Law, an accommodating party lends his credit to the accommodated party, by issuing or indorsing a check which is held by a payee or indorsee as a holder in due course, who gave full value therefor to the accommodated party. The

latter, in other words, receives or realizes full value which the accommodated party then must repay to the accommodating party, unless of course the accommodating party intended to make a donation to the accommodated party. But the accommodating party is bound on the check to the holder in due course who is necessarily a third party and is not the accommodated party. Having issued or indorsed the check, the accommodating party has warranted to the holder in due course that he will pay the same according to its tenor. 4. ID.; ID.; ID.; LIABILITY OF DRAWER IN THE ABSENCE OF PROOF THEREOF; CASE AT BAR. In the case at bar, Travel-On was payee of all six (6) checks; it presented these checks for payment at the drawee bank but the checks bounced. Travel-On obviously was not an accommodated party; it realized no value on the checks which bounced. Travel-On was entitled to the benefit of the statutory presumption that it was a holder in due course, that the checks were supported by valuable consideration. Private respondent maker of the checks did not successfully rebut these presumptions. The only evidence aliunde that private respondent offered was his own self-serving uncorroborated testimony. He claimed that he had issued the checks to Travel-On as payee to "accommodate" its General Manager who allegedly wished to show those checks to the Board of Directors of Travel-On to "prove" the Travel-On's account receivable were somehow "still good." It will be seen that this claim was in fact a claim that the checks were merely simulated, that private respondent did not intend to bind himself thereon. Only evidence of the clearest and most convincing kind will suffice for that purpose; no such evidence was submitted by private respondent. The latter's explanation, was denied by Travel-On's General Manager; that explanation in any case, appears merely contrived and quite hollow to us. Upon the other hand, the accommodation" or assistance extended to Travel-On's passengers abroad as testified by petitioner's General Manager involved, not the accommodation transactions recognized by the NIL, but rather the circumvention of them existing foreign exchange regulations by passengers booked by Travel-On, which incidentally involved receipt of full consideration by private respondent. Thus, we believe and so hold that private respondent must be held liable on the six (6) checks here involved. Those checks in themselves constituted evidence of indebtedness of private respondent, evidence not successfully overturned or rebutted by private respondent

27. bpi v. ca (parang walang nego,idk) 1. TAXATION; TAX CODE; CORPORATION ENTITLED TO REFUND; OPTIONS. It is undisputed that petitioner had excess withholding taxes for the year 1989 and was thus entitled to a refund amounting to P112,491. Pursuant to Section 69 of the 1986 Tax Code which states that a corporation entitled to a refund may opt either (1) to obtain such refund or (2) to credit said amount for the succeeding taxable year. 2. REMEDIAL LAW; EVIDENCE; FACTUAL FINDINGS OF APPELLATE COURT, GENERALLY RESPECTED; EXCEPTION. As a rule, the factual findings of the appellate court are binding on this Court. This rule, however, does not apply where, inter alia, the judgment is premised on a

misapprehension of facts, or when the appellate court failed to notice certain relevant facts which if considered would justify a different conclusion. This case is one such exception. 3. TAXATION; COURT OF TAX APPEALS; RULES OF PROCEEDINGS THEREIN NOT STRICTLY CONSTRUED. Strict procedural rules generally frown upon the submission of the Return after the trial. The law creating the Court of Tax Appeals, however, specifically provides that proceedings before it "shall not be governed strictly by the technical rules of evidence." The paramount consideration remains the ascertainment of truth. Verily, the quest for orderly presentation of issues is not an absolute. It should not bar courts from considering undisputed facts to arrive at a just determination of a controversy. It should be stressed that the rationale of the rules of procedure is to secure a just determination of every action. They are tools designed to facilitate the attainment of justice. But there can be no just determination of the present action if we ignore, on grounds of strict technicality, the Return submitted before the CTA and even before this Court. 4. REMEDIAL LAW; EVIDENCE; JUDICIAL NOTICE; RULE. As a rule, "courts are not authorized to take judicial notice of the contents of the records of other cases, even when such cases have been tried or are pending in the same court, and notwithstanding the fact that both cases may have been heard or are actually pending before the same judge." Be that as it may, Section 2, Rule 129 provides that courts may take judicial notice of matters ought to be known to judges because of their judicial functions. 5. TAXATION; TAX REFUNDS; APPRECIATION THEREOF. Respondents argue that tax refunds are in the nature of tax exemptions and are to be construed strictissimi juris against the claimant. Under the facts of this case, we hold that petitioner has established its claim. Petitioner may have failed to strictly comply with the rules of procedure; it may have even been negligent. These circumstances, however, should not compel the Court to disregard this cold, undisputed fact: that petitioner suffered a net loss in 1990, and that it could not have applied the amount claimed as tax credits. Substantial justice, equity and fair play are on the side of petitioner. Technicalities and legalisms, however exalted, should not be misused by the government to keep money not belonging to it and thereby enrich itself at the expense of its law-abiding citizens. If the State expects its taxpayers to observe fairness and honesty in paying their taxes, so must it apply the same standard against itself in refunding excess payments of such taxes. Indeed, the State must lead by its own example of honor, dignity and uprightness. SDIaCT 28. agro conglomerates inc. vs.CA ID.; ID.; ACCOMMODATION PARTY; ELUCIDATED. An accommodation party is a person who has signed the instrument as maker, acceptor, or indorser, without receiving value therefor, and for the purpose of lending his name to some other person and is liable on the instrument to a holder for value, notwithstanding such holder at the time of taking the instrument knew (the signatory) to be an accommodation party. He has the right, after paying the holder, to obtain reimbursement from the party accommodated, since the relation between them has in effect become one of principal and surety, the accommodation party being the surety.

29. de ocampo v. gatchalian 1. BILLS, NOTES AND CHECKS; NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS; HOLDER IN DUE COURSE. Section 52 (c) provides that a holder in due course is one who takes the instrument "in good faith and for value;" Section 59, "that every holder is deemed prima facie to be holder in due course;" and Section 52 (d), that in order that one may be a holder in due course it is necessary that "at the time the instrument was negotiated" to him "he had no notice of any . . . defect in the title of the person negotiating it;" and lastly Section 59, that every holder is deemed prima facie to be a holder in due course. 2. ID.; ID.; WHEN A HOLDER IS NOT A HOLDER IN DUE COURSE. Where a holder's title is defective or suspicious, it cannot be stated that the payee acquired the check without the knowledge of said defect in holder's title, and for this reason the presumption that it is a holder in due course or that it acquired the instrument in good faith does not exist. 3. ID.; ID.; HOLDER IN DUE COURSE; WHEN PROOF OF GOOD FAITH REQUIRED. Where the payee acquired the check under circumstances which should have put it to inquiry, why the holder had the check and used it, to pay his own personal account, the duty devolved upon it to prove that it actually acquired said check in good faith

30. mesina v. IAC 31. metropol v. sambok 1. MERCANTILE LAW; PROMISSORY NOTE; QUALIFIED INDORSEMENT; EFFECT THEREOF. A qualified indorsement constitutes the indorser a mere assignor of the title to the instrument. It may be made by adding to the indorser's signature the words "without recourse" or any words of similar import. Such an indorsement relieves the indorser of the general obligation to pay if the instrument is dishonored but not of the liability arising from warranties on the instrument as provided in Section 65 of the Negotiable Instruments Law. However, appellant Sambok indorse the note "with recourse'' and even waived the notice of demand, dishonor, protest and presentment. 2. ID.; ID.; ADDITION OF THE WORDS "WITH RECOURSE" DO NOT MAKE THE INDORSEMENT QUALIFIED; CASE AT BAR. Appellant, by indorsing the note "with recourse'' does not make itself a qualified indorser but a general indorser who is secondarily liable, because by such indorsement, it agreed that if Dr. Villaruel fails to pay the note, plaintiff-appellee can go after said appellant. The effect of such indorsement is that the note was indorsed without qualification. A person who indorses without qualification engages that on due presentment, the note shall be accepted or paid, or both as the case may be, and that if it be dishonored, he will pay the amount thereof to the holder. Appellant Sambok's intention of indorsing the note without qualification is made even more apparent by the fact that the notice of' demand, dishonor, protest and presentment were all waived. The words added by said appellant do not limit his liability, but rather confirm his obligations as a general indorser.

3. ID.; ID.; AFTER DISHONORED BY NON-PAYMENT, PERSON SECONDARILY LIABLE BECOMES THE PRINCIPAL DEBTOR. The lower court did not err in not declaring appellant as only secondarily liable because after an instrument is dishonored by, non-payment. the person secondarily liable thereon ceases to be such and becomes a principal debtor. His liability becomes the same as that of the original obligor. Consequently, the holder need not even proceed against the maker before suing the indorser

32. maralit v. imperial

33. sapiera v. court of appeals

MERCANTILE LAW; NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS; PERSON DEEMED AN INDORSER WHEN SHE SIGNED BACK OF CHECK WITHOUT INDICATION AS TO HOW SHE SHOULD BE BOUND THEREBY. It is undisputed that the four (4) checks issued by de Guzman were signed by petitioner at the back without any indication as to how she should be bound thereby and, therefore, she is deemed to be an indorser thereof. 34. BPI v. court of appeals COMMERCIAL LAW; NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW; WARRANTIES OF A PERSON NEGOTIATING AN INSTRUMENT; APPLICATION IN CASE AT BAR. Section 65, on the other hand, provides for the following warranties of a person negotiating an instrument by delivery or by qualified indorsement: (a) that the instrument is genuine and in all respects what it purports to be; (b) that he has a good title to it; and (c) that all prior parties had capacity to contract. In People vs. Maniego, this Court described the liabilities of an indorser as follows: "Appellant's contention that as mere indorser, she may not be liable on account of the dishonor of the checks indorsed by her, is likewise untenable. Under the law, the holder or last indorsee of a negotiable instrument has the right 'to enforce payment of the instrument for the full amount thereof against all parties liable thereon.' Among the 'parties liable thereon' is an indorser of the instrument, i.e., 'a person placing his signature upon an instrument otherwise than as a maker, drawer or acceptor ** unless he clearly indicated by appropriate words his intention to be bound in some other capacity.' Such an indorser 'who indorses without qualification,' inter alia 'engages that on due presentment, ** (the instrument) shall be accepted or paid, or both, as the case may be, according to its tenor, and that if it be dishonored, and the necessary proceedings on dishonor be duly taken, he will pay the amount thereof to the holder, or any subsequent indorser who may be compelled to pay it.' Maniego may also be deemed an 'accommodation party' in the light of the facts, i.e., a person 'who has signed the instrument as maker, drawer, acceptor, or indorser, without receiving value therefor, and for the purpose of lending his name to some other person.' As such, she is under the law 'liable on the instrument to a holder for value, notwithstanding such holder

at the time of taking the instrument knew ** (her) to be only an accommodation party,' although she has the right, after paying the holder, to obtain reimbursement from the party accommodated, 'since the relation between them is in effect that of principal and surety, the accommodation party being the surety.'" It is thus clear that ordinarily private respondent may be held liable as an indorser of the check or even as an accommodation party. However, to hold private respondent liable for the amount of the check he deposited by the strict application of the law and without considering the attending circumstances in the case would result in an injustice and in the erosion of the public trust in the banking system. The interest of justice thus demands looking into the events that led to the encashment of the check. 2. ID.; ID.; CHECK DEPOSIT; COLLECTING BANK OR LAST ENDORSER SUFFERS THE LOSS, AS A GENERAL RULE; RATIONALE; CASE AT BAR. As correctly held by the Court of Appeals, in depositing the check in his name, private respondent did not become the outright owner of the amount stated therein. Under the above rule, by depositing the check with petitioner, private respondent was, in a way, merely designating petitioner as the collecting bank. This is in consonance with the rule that a negotiable instrument, such as a check, whether a manager's check or ordinary check, is not legal tender. As such, after receiving the deposit, under its own rules, petitioner shall credit the amount in private respondent's account or infuse value thereon only after the drawee bank shall have paid the amount of the check or the check has been cleared for deposit. Again, this is in accordance with ordinary banking practices and with this Court's pronouncement that "the collecting bank or last endorser generally suffers the loss because it has the duty to ascertain the genuineness of all prior endorsements considering that the act of presenting the check for payment to the drawee is an assertion that the party making the presentment has done its duty to ascertain the genuineness of the endorsements." The rule finds more meaning in this case where the check involved is drawn on a foreign bank and therefore collection is more difficult than when the drawee bank is a local one even though the check in question is a manager's check. Said ruling brings to light the fact that the banking business is affected with public interest. By the nature of its functions, a bank is under obligation to treat the accounts of its depositors "with meticulous care, always having in mind the fiduciary nature of their relationship."

35. prudential bank v. IAC 1. COMMERCIAL LAW; NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS; LETTER OF CREDIT; CONSTRUED. A letter of credit is defined as an engagement by a bank or other person made at the request of a customer that the issuer will honor drafts or other demands for payment upon compliance with the conditions specified in the credit. Through a letter of credit, the bank merely substitutes its own promise to pay for the promise to pay of one of its customers who in return promises to pay the bank the amount of funds mentioned in the letter of credit plus credit or commitment fees mutually agreed upon. 2. ID.; ID.; ID.; PRESENTMENT FOR ACCEPTANCE, NOT NECESSARY IN CASE AT BAR. The transaction in the case at bar stemmed from Philippine Rayon's application for a commercial letter of

credit with the petitioner in the amount of $128,548.78 to cover the former's contract to purchase and import loom and textile machinery from Nissho Company, Ltd. of Japan under a five-year deferred payment plan. Petitioner approved the application. The drawee was necessarily the herein petitioner. It was to the latter that the drafts were presented for payment. There was no need for acceptance as the issued drafts are sight drafts. They are, pursuant to Section 7 of the Negotiable Instruments Law (NIL), payable on demand. Presentment for acceptance is defined as the production of a bill of exchange to a drawee for acceptance. Contrary to both courts' pronouncements, Philippine Rayon immediately became liable thereon upon petitioner's payment thereof. Such is the essence of the letter of credit issued by the petitioner. A different conclusion would violate the principle upon which commercial letters of credit are founded because in such a case, both the beneficiary and the issuer, Nissho Company Ltd. and the petitioner, respectively, would be placed at the mercy of Philippine Rayon even if the latter had already received the imported machinery and the petitioner had fully paid for it. Presentment for acceptance is necessary only in the cases expressly provided for in Section 143 of the Negotiable Instruments Law (NIL). 3. ID.; ID.; ACCEPTANCE OF A BILL, EXPLAINED. The acceptance of a bill is the signification by the drawee of his assent to the order of the drawer; this may be done in writing by the drawee in the bill itself, or in a separate instrument.

36. wong v. CA RIMINAL LAW; BOUNCING CHECKS LAW (B.P. Blg. 22); CIVIL INDEMNITY TO BE IMPOSED; CASE AT BAR. Finding his motion for reconsideration meritorious but only with respect to the prayer for recomputation of civil indemnity to be imposed; we now set the amount thereof to only P15,285.00, which is the correct sum of the face value of the three checks involved in the present case. ACCORDINGLY, the dispositive portion of our Decision in this case is hereby amended to read as follows: "WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. Petitioner Luis S. Wong is found liable for violation of Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 but the penalty imposed on him is hereby MODIFIED so that the sentence of imprisonment is deleted. Petitioner is ORDERED to pay a FINE of (1) P6,750.00, equivalent to double the amount of the check involved in Criminal Case No. CBU-12057, (2) P12,820.00, equivalent to double the amount of the check involved in Criminal Case No. CBU-12058, and (3) P11,000.00, equivalent to double the amount of the check involved in Criminal Case No. CBU-12055, with subsidiary imprisonment in case of insolvency to pay the aforesaid fines. Finally, as civil indemnity, petitioner is also ordered to pay to LPI the face value of said checks totaling P15,285.00 with legal interest thereon from the time of filing the criminal charges in court, as well as to pay the costs." cITAaD 37. international corporate bank v. sps. Francis gueco COMMERCIAL LAW; NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS; CHECKS; STALE CHECK, DEFINED. A stale check is one which has not been presented for payment within a reasonable time after its issue. It is valueless and, therefore, should not be paid. Under the negotiable instruments law, an instrument not payable

on demand must be presented for payment on the day it falls due. When the instrument is payable on demand, presentment must be made within a reasonable time after its issue. In the case of a bill of exchange, presentment is sufficient if made within a reasonable time after the last negotiation thereof. 5. ID.; ID.; ID.; MUST BE PRESENTED WITHIN REASONABLE TIME FROM ISSUE. A check must be presented for payment within a reasonable time after its issue, and in determining what is a "reasonable time," regard is to be had to the nature of the instrument, the usage of trade or business with respect to such instruments, and the facts of the particular case. The test is whether the payee employed such diligence as a prudent man exercises in his own affairs. This is because the nature and theory behind the use of a check points to its immediate use and payability. 6. ID.; ID.; ID.; MANAGER'S CHECK, SIMILAR TO CASHIER'S CHECK BOTH AS TO ISSUE AND USE. In the case at bar, however, the check involved is not an ordinary bill of exchange but a manager's check. A manager's check is one drawn by the bank's manager upon the bank itself. It is similar to a cashier's check both as to effect and use. A cashier's check is a check of the bank's cashier on his own or another check. In effect, it is a bill of exchange drawn by the cashier of a bank upon the bank itself, and accepted in advance by the act of its issuance. It is really the bank's own check and may be treated as a promissory note with the bank as a maker. The check becomes the primary obligation of the bank which issues it and constitutes its written promise to pay upon demand. The mere issuance of it is considered an acceptance thereof. If treated as promissory note, the drawer would be the maker and in which case the holder need not prove presentment for payment or present the bill to the drawee for acceptance. 7. ID.; ID.; ID.; FAILURE TO PRESENT MANAGER'S CHECK WITHIN REASONABLE TIME DOES NOT TOTALLY WIPE OUT ALL LIABILITY. Even assuming that presentment is needed, failure to present for payment within a reasonable time will result to the discharge of the drawer only to. the extent of the loss caused by the delay. Failure to present on time, thus, does not totally wipe out all liability. In fact, the legal situation amounts to an acknowledgment of liability in the sum stated in the check. In this case, the Gueco spouses have not alleged, much less shown that they or the bank which issued the manager's check has suffered damage or loss caused by the delay or non-presentment. Definitely, the original obligation to pay certainly has not been erased. It has been held that, if the check had become stale, it becomes imperative that the circumstances that caused its non-presentment be determined. In the case at bar, there is no doubt that the petitioner bank held on the check and refused to encash the same because of the controversy surrounding the signing of the joint motion to dismiss. We see no bad faith or negligence in this position taken by the Bank 38. state investment house v. CA 39. bataan cigar v. court of appeals COMMERCIAL LAW; NEGOTIABLE INSTRUMENTS LAW; HOLDER IN DUE COURSE; REQUISITES. The Negotiable Instruments Law states what constitutes a holder in due course, thus: "Sec. 52 - A holder in due course is a holder who has taken the instrument under the following conditions: (a) That it is

complete and regular upon its face; (b) That he became the holder of it before it was overdue, and without notice that it had been previously dishonored, if such was the fact; (c) That he took it in good faith and for value; (d) That at the time it was negotiated to him he had no notice of any infirmity in the instrument or defect in the title of the person negotiating it." 2. ID.; ID.; EVERY HOLDER DEEMED PRIMA FACIE HOLDER IN DUE COURSE. Section 59 of the NIL further states that every holder is deemed prima facie a holder in due course. However, when it is shown that the title of any person who has negotiated the instrument was defective, the burden is on the holder to prove that he or some person under whom he claims, acquired the title as holder in due course. 3. ID.; ID.; CHECK; DEFINED. A check is defined by law as a bill of exchange drawn on a bank payable on demand. 4. ID.; ID.; ID.; CROSSED CHECK; KINDS. Crossed check is one where two parallel lines are drawn across its face or across a corner thereof. It may crossed generally or specially. A check is crossed specially when the name of a particular banker or a company is written between the parallel lines drawn. It is crossed generally when only the words "and company" are written or nothing is written at all between the parallel lines. It may be issued so that presentment can be made only by a bank. Veritably the Negotiable Instruments Law (NIL) does not mention "crossed checks," although Article 541 of the Code of Commerce refers to such instruments. 5. ID.; ID.; ID.; NEGOTIABILITY NOT AFFECTED BY ITS BEING CROSSED. According to commentators, the negotiability of a check is not affected by its being crossed, whether specially or generally. It may legally be negotiated from one person to another as long as the one who encashes the check with the drawee bank is another bank, or if it is especially crossed, by the bank mentioned between the parallel lines. This is specially true in England where the Negotiable Instrument Law originated. 6. ID.; ID.; ID.; EFFECTS OF CROSSING A CHECK. Crossing of a check should have the following effects: (a) the check may not be encashed but only deposited in the bank; (b) the check may be negotiated only once to one who has an account with a bank; (c) and the act of crossing the check serves as warning to the holder that the check has been issued for a definite purpose so that he must inquire if he has received the check pursuant to that purpose, otherwise, he is not a holder in due course. 7. ID.; ID.; ID.; CROSSING OF CHECK SHOULD PUT HOLDER ON INQUIRY; EFFECT OF OMISSION THEREOF. It is then settled that crossing of checks should put the holder on inquiry and upon him devolves the duty to ascertain the indorser's title to the check or the nature of his possession. Failing in this respect, the holder is declared guilty of gross negligence amounting to legal absence of good faith, contrary to Sec. 52(c) of the Negotiable Instruments Law, and as such the consensus of authority is to the effect that the holder of the check is not a holder in due course.

8. ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; DRAWER NOT OBLIGED TO PAY CHECKS; CASE AT BAR. In the present case, BCCFI's defense in stopping payment is as good to SIHI as it is to George King. Because, really, the checks were issued with the intention that George King would supply BCCFI with the bales of tobacco leaf. There being failure of consideration, SIHI is not a holder in due course. Consequently, BCCFI cannot be obliged to pay the checks. 9. ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; ID.; HOLDER CAN STILL COLLECT FROM IMMEDIATE INDORSER. The foregoing does not mean, however, that respondent could not recover from the checks. The only disadvantage of a holder who is not a holder in due course is that the instrument is subject to defenses as if it were non-negotiable. Hence, respondent can collect from the immediate indorser, in this case, George King. 40. citytrust banking corp. iac (idk,walang nego) CIVIL LAW; DAMAGES; TEMPERATE OR MODERATE DAMAGES NOT GRANTED CONCURRENTLY WITH NOMINAL DAMAGES; REASON; CASE AT BAR. It is wrong to award, along with nominal damages, temperate or moderate damages. The two awards are incompatible and cannot be granted concurrently. Nominal damages are given in order that a right of the plaintiff, which has been violated or invaded by the defendant, may be vindicated or recognized, and not for the purpose of indemnifying the plaintiff for any loss suffered by him (Art. 2221, New Civil Code; Manila Banking Corp. vs. Intermediate Appellate Court, 131 SCRA 271). Temperate or moderate damages, which are more than nominal but less than compensatory damages, on the other hand, may be recovered when the court finds that some pecuniary loss has been suffered but its amount cannot, from the nature of the case, be proved with reasonable certainty (Art. 2224, New Civil Code). In the instant case, we also find need for vindicating the wrong done on private respondent, and we accordingly agree with the Court of Appeals in granting to her nominal damages but not in similarly awarding temperate or moderate damages.

41. tan v. ca 42. papa v. AU Valenciaand Co. 1. CIVIL LAW; OBLIGATIONS AND CONTRACTS; PAYMENT BY CHECK; WHEN CONDITIONED ON ITS BEING CASHED EXCEPT THROUGH THE FAULT OF THE CREDITOR THE INSTRUMENT IS IMPAIRED; WHERE NON-PAYMENT IS CAUSED BY HIS NEGLIGENCE, PAYMENT IS DEEMED EFFECTED. While it is true that the delivery of a cheek produces the effect of payment only when it is cashed, pursuant to Art. 1249 of the Civil Code, the rule is otherwise if the debtor is prejudiced by the creditor's unreasonable delay in presentment. The acceptance of a check implies an undertaking of due diligence in presenting it for payment, and if he from whom it is received sustains loss by want of such diligence, it will be held to operate as actual payment of the debt or obligation for which it was given. It has, likewise, been held that if no presentment is made at all, the drawer cannot be held liable irrespective of loss or injury unless presentment is otherwise excused. This is in harmony with Article

1249 of the Civil Code under which payment by way of check or other negotiable instrument is conditioned on its being cashed, except when through the fault of the creditor, the instrument is impaired. The payee of a check would be a creditor under this provision and if its non-payment is caused by his negligence, payment will be deemed effected and the obligation for which the check was given as conditional payment will be discharged. 2. REMEDIAL LAW; ACTIONS; APPROPRIATE ACTION MAY BE FILLED TO ENFORCE A LIEN ON AN ASSIGNMENT OF MORTGAGE RIGHTS; ACTION DIFFERENT FROM SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE; CASE AT BAR. We regard to the alleged assignment of mortgage rights, respondent Court of Appeals has found that the conditions under which said mortgage rights of the bank were assigned are not clear. Indeed, a perusal of the original records of the case would show that there is nothing there that could shed light on the transactions leading to the said assignment of rights; nor is there any evidence on record of the conditions under which said mortgage rights were assigned. What is certain is that despite the said assignment of mortgage rights, the title to the subject property has remained in the name of the late Angela M. Butte. This much is admitted by petitioner himself in his answer to respondents' complaint as well as in the third party complaint that petitioner filed against respondent-spouses Arsenio B. Reyes and Amanda Santos. Assuming arguendo that the mortgage rights of the Associated Citizens Bank had been assigned to the estate of Ramon Papa, Jr., and granting that the assigned mortgage rights validly exist and constitute a lien on the property, the estate may file the appropriate action to enforce such lien. The cause of action for specific performance which respondents Valencia and Pearroyo have against petitioner is different from the cause of action which estate of Ramon Papa, Jr. may have to enforce whatever rights or liens it has on the property by reason of its being an alleged assignee of the bank's rights of mortgage. 3. ID.; ID.; REPRESENTATIVE PARTIES; AN EXECUTOR OR ADMINISTRATOR MAY BE SUED WITHOUT GOING THE ESTATE OF THE DECEASED. Finally, the estate of Angela M. Butte is not an indispensable party. Under Section 3 of Rule 3 of the Rules of Court, an executor or administrator may sue or be sued without joining the party for whose benefit the action is presented or defended. 4. ID.; ID.; SUBSISTING AND PRIOR MORTGAGE RIGHTS MAY BE ENFORCED REGARDLESS OF CHANGE OF OWNERSHIP. Neither is the estate of Ramon Papa, Jr. an indispensable party without whom, no final determination of the action can be had. Whatever prior and subsisting mortgage rights the estate of Ramon Papa, Jr. has over the property may still be enforced regardless of the change in ownership thereof.

ADDITIONAL CASES: 1. Allied Banking Corp.v. VA 2. Sincere Villanueva v. Marlyn Nite

3. ID.; ID.; ID.; PRESENTATION OF CHECK FOR PAYMENT WITHIN THE 90-DAY PERIOD FROM ITS ISSUANCE, NOT AN ELEMENT OF OFFENSE. The fact that the checks were presented beyond the 90day period provided in Section 2 of B.P. Blg. 22 is of no moment. We held that the 90-day period is not an element of the offense but merely a condition for the prima facie presumption of knowledge of the insufficiency of funds; thus: That the check must be deposited within ninety (90) days is simply one of the conditions for the prima facie presumption of knowledge of lack of funds to arise. It is not an element of the offense. Neither does it discharge petitioner from his duty to maintain sufficient funds in the account within a reasonable time thereof. Under Section 186 of the Negotiable Instruments Law, "a check must be presented for payment within a reasonable time after its issue or the drawer will be discharged from liability thereon to the extent of the loss caused by the delay." By current banking practice, a check becomes stale after more than six (6) months, or 180 days. In Bautista v. Court of Appeals, we ruled that such prima facie presumption is intended to facilitate proof of knowledge, and not to foreclose admissibility of other evidence that may also prove such knowledge; thus, the only consequence of the failure to present the check for payment within the 90-day period is that there arises no prima facie presumption of knowledge of insufficiency of funds. The prosecution may still prove such knowledge through other evidence. HDICSa 3. BPI v. CIR 4. Citibank v. sabeniano 5. equitable PCI bank v. Ong 6.

You might also like

- Tax Booklet As of 10 November 2016 PDFDocument20 pagesTax Booklet As of 10 November 2016 PDFmaronbNo ratings yet

- Sample Fin Support LTRDocument1 pageSample Fin Support LTRStephano HawkingNo ratings yet

- How To Argue and Win Every TimeDocument24 pagesHow To Argue and Win Every TimeMeiHong Lynn Wong100% (1)

- 2015 Bar Exam ResultsDocument79 pages2015 Bar Exam ResultsBryner Laurito DiazNo ratings yet

- Small ClaimsDocument66 pagesSmall ClaimsarloNo ratings yet

- PSBank Auto Mart Bid Form - 2017 01 20Document1 pagePSBank Auto Mart Bid Form - 2017 01 20Stephano HawkingNo ratings yet

- Retainer Agreement Legal ServicesDocument4 pagesRetainer Agreement Legal ServicesStephano HawkingNo ratings yet

- 97 589 PDFDocument57 pages97 589 PDFYu Gen XinNo ratings yet

- Efficient Use of Paper Rule A.M. No. 11-9-4-SCDocument3 pagesEfficient Use of Paper Rule A.M. No. 11-9-4-SCRodney Atibula100% (3)

- Dean Jara Lecture Notes in Remedial LawDocument473 pagesDean Jara Lecture Notes in Remedial LawStephano Hawking100% (1)

- Wage Order No. NCR-19Document40 pagesWage Order No. NCR-19Stephano HawkingNo ratings yet

- IRR For RA 8042, RA 10022Document60 pagesIRR For RA 8042, RA 10022Stephano HawkingNo ratings yet

- Poea Rules and Regulations On Recruitment and EmploymentDocument39 pagesPoea Rules and Regulations On Recruitment and EmploymentkwinrayNo ratings yet

- IRR of Domestic Workers ActDocument24 pagesIRR of Domestic Workers ActRamil Sotelo SasiNo ratings yet

- Tabulation of The Provisions of The Application of PenaltiesDocument1 pageTabulation of The Provisions of The Application of PenaltiesStephano HawkingNo ratings yet

- IRR For RA 8042Document18 pagesIRR For RA 8042Stephano HawkingNo ratings yet

- Voter's Registration ActDocument18 pagesVoter's Registration ActStephano HawkingNo ratings yet

- Local Government Code of The PhilippinesDocument281 pagesLocal Government Code of The PhilippinesAbdul Halim ReveloNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Piercing Corporate Veil DoctrineDocument2 pagesPiercing Corporate Veil DoctrineJude Thaddeus DamianNo ratings yet

- Complaint Against Barangay CaptainDocument3 pagesComplaint Against Barangay CaptainReynil C. ArcideNo ratings yet

- Ong V CADocument2 pagesOng V CAIhna Alyssa Marie SantosNo ratings yet

- CA upholds conviction of man for selling shabuDocument6 pagesCA upholds conviction of man for selling shabuJomai siomaiNo ratings yet

- Road Test WaiverDocument2 pagesRoad Test Waiverdhamo daranNo ratings yet

- GROUP 1 - Sec 53-58Document3 pagesGROUP 1 - Sec 53-58Joris YapNo ratings yet

- Pre Trial BriefDocument6 pagesPre Trial BriefMelody MANo ratings yet

- Rule 58 Cases Full TextDocument95 pagesRule 58 Cases Full TextChrissy SabellaNo ratings yet

- MarrySuanNotes SALES CaseDigest2015Document64 pagesMarrySuanNotes SALES CaseDigest2015Angel DeiparineNo ratings yet

- Banco Filipino V Ybanez Digest2Document3 pagesBanco Filipino V Ybanez Digest2Kenny Robert'sNo ratings yet

- Def MTDDocument24 pagesDef MTDHilary LedwellNo ratings yet

- Criminology & Penology - Dr. Swati MehtaDocument3 pagesCriminology & Penology - Dr. Swati MehtaPuneet TiggaNo ratings yet

- Merlina Diaz V PPDocument2 pagesMerlina Diaz V PPErca Gecel BuquingNo ratings yet

- Jesica Oseguera Mencho Daughter PleaDocument99 pagesJesica Oseguera Mencho Daughter PleaChivis MartinezNo ratings yet

- Same Tractor Corsaro 70 Parts CatalogDocument11 pagesSame Tractor Corsaro 70 Parts Catalogmatthewperry151099kmr100% (29)

- Traditional Approaches and Modern Conflict of Laws TheoriesDocument19 pagesTraditional Approaches and Modern Conflict of Laws Theoriesthadalts50% (2)

- Gonzales Vs GonzalesDocument6 pagesGonzales Vs GonzalesJohnRouenTorresMarzoNo ratings yet

- SSS v. DavacDocument7 pagesSSS v. DavacIhna Alyssa Marie SantosNo ratings yet

- Contracts: Mbe Practice QuestionsDocument16 pagesContracts: Mbe Practice QuestionsStacy OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Penal CodeDocument2 pagesPakistan Penal CodeSalman Ali MastNo ratings yet

- Suraj Mani Judge Ment.Document2 pagesSuraj Mani Judge Ment.shivam jainNo ratings yet

- Flash Bang ReplyDocument39 pagesFlash Bang ReplyWilliam N. GriggNo ratings yet

- Legal Latin Maxims and PhrasesDocument30 pagesLegal Latin Maxims and PhrasesTyrelle CastilloNo ratings yet

- STEWART, ANASTASIA THERESA Et Al v. SUNJET AVIATDKN INC, Et Al DocketDocument60 pagesSTEWART, ANASTASIA THERESA Et Al v. SUNJET AVIATDKN INC, Et Al DocketbombardierwatchNo ratings yet

- Everett Steamship Corporation Case DigestDocument2 pagesEverett Steamship Corporation Case Digestalexredrose0% (1)

- Allotted To: 16002 - 16004 16009-16015 16019 - 16021 16028 - 16033 16040 - 16041Document2 pagesAllotted To: 16002 - 16004 16009-16015 16019 - 16021 16028 - 16033 16040 - 16041NavneetNo ratings yet

- Inquiry Complaint FormDocument4 pagesInquiry Complaint FormAlexandra LukeNo ratings yet

- BetweenDocument13 pagesBetweenBrian ChukwuraNo ratings yet

- Judicial Affidavit JebbDocument6 pagesJudicial Affidavit JebbAdrian CabahugNo ratings yet

- US Vs RamosDocument2 pagesUS Vs RamosJames OcampoNo ratings yet