Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FAO Introduction To FS

Uploaded by

Bin LiuOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FAO Introduction To FS

Uploaded by

Bin LiuCopyright:

Available Formats

An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security

I. THE FOUR DIMENSIONS OF FOOD SECURITY

Food Security Information for Action

Practical Guides

Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

- 1996 World Food Summit

From this definition, four main dimensions of food security can be identified: Physical AVAILABILITY of food Economic and physical ACCESS to food Food UTILIZATION

Food availability addresses the supply side of food security and is determined by the level of food production, stock levels and net trade. An adequate supply of food at the national or international level does not in itself guarantee household level food security. Concerns about insufficient food access have resulted in a greater policy focus on incomes, expenditure, markets and prices in achieving food security objectives. Utilization is commonly understood as the way the body makes the most of various nutrients in the food. Sufficient energy and nutrient intake by individuals is the result of good care and feeding practices, food preparation, diversity of the diet and intra-household distribution of food. Combined with good biological utilization of food consumed, this determines the nutritional status of individuals. Even if your food intake is adequate today, you are still considered to be food insecure if you have inadequate access to food on a periodic basis, risking a deterioration of your nutritional status. Adverse weather conditions, political instability, or economic factors (unemployment, rising food prices) may have an impact on your food security status.

STABILITY of the other three dimensions over time

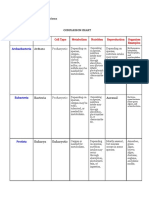

For food security objectives to be realized, all four dimensions must be fulfilled simultaneously. II. THE DURATION OF FOOD INSECURITY Food security analysts have defined two general types of food insecurity:

CHRONIC FOOD INSECURITY

TRANSITORY FOOD INSECURITY

is... occurs when... results from...

long-term or persistent. people are unable to meet their minimum food requirements over a sustained period of time. extended periods of poverty, lack of assets and inadequate access to productive or financial resources. typical long term development measures also used to address poverty, such as education or access to productive resources, such as credit. They may also need more direct access to food to enable them to raise their productive capacity.

short-term and temporary. there is a sudden drop in the ability to produce or access enough food to maintain a good nutritional status. short-term shocks and fluctuations in food availability and food access, including year-to-year variations in domestic food production, food prices and household incomes. transitory food insecurity is relatively unpredictable and can emerge suddenly. This makes planning and programming more difficult and requires different capacities and types of intervention, including early warning capacity and safety net programmes ( see Box 1).

can be overcome with...

The concept of seasonal food security falls between chronic and transitory food insecurity. It is similar to chronic food insecurity as it is usually predictable and follows a sequence of known events. However, as seasonal food insecurity is of limited duration it can also be seen as recurrent, transitory food insecurity. It occurs when there is a cyclical pattern of inadequate availability and access to food. This is associated with seasonal fluctuations in the climate, cropping patterns, work opportunities (labour demand) and disease.

The EC - FAO Food Security Programme is funded by the European Union and implemented by FAO

An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security

Box 1. What are Safety Nets?

Food Security Information for Action

Practical Guides

Measures to enhance direct access to food are more likely to be beneficial if these are embedded in more general social safety net programmes. Safety nets include income transfers for those chronically unable to workbecause of age or handicapsand for those temporarily affected by natural disasters or economic recession. Options include: Targeted direct feeding programmes. These include school meals; feeding of expectant and nursing mothers as well as children under five through primary health centres, soup kitchens and special canteens. Food-for-work programmes. Food-for-work programmes provide support to households while developing useful infrastructure such as small-scale irrigation, rural roads, buildings for rural health centres and schools. Income-transfer programmes. These can be in cash or in kind, including food stamps, subsidized rations and other targeted measures for poor households.

Stamoulis, K. and Zezza, A. 2003. A Conceptual Framework for National Agricultural, Rural Development, and Food Security Strategies and Policies. ESA Working Paper No. 03-17, November 2003. Agricultural and Development Economics Division, FAO, Rome. www. fao.org/documents/show_cdr.asp?url_file=/docrep/007/ae050e/ ae050e00.htm

The severity of undernourishment indicates, for the food deprived, the extent to which dietary energy consumption falls below the pre-determined threshold. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) The IPC is a classification system for food security crises based on a range of livelihood needs:

IPC Phase Classification Generally food secure Chronically food insecure Acute food and livelihood crisis Humanitarian emergency Famine / humanitarian catastrophe Indicators - Crude Mortality Rate - Malnutrition prevalence - Food Access/ Availability - Dietary Diversity - Water Access/Availability - Coping strategies - Livelihood Assets

See www.ipcinfo.org for more information

IV. VULNERABILITY The dynamic nature of food security is implicit when we talk about people who are vulnerable to experiencing food insecurity in the future. Vulnerability is defined in terms of the following three critical dimensions: 1. vulnerability to an outcome; 2. from a variety of risk factors; 3. because of an inability to manage those risks. Indeed, a person can be vulnerable to hunger even if he or she is not actually hungry at a given point in time. Vulnerability analysis suggests two main intervention options: 1. Reduce the degree of exposure to the hazard; 2. Increase the ability to cope. By accounting for vulnerability, food security policies and programs broaden their efforts from addressing current constraints to food consumption, to include actions that also address future threats to food security.

III. THE SEVERITY OF FOOD INSECURITY When analyzing food insecurity, it is not enough to know the duration of the problem that people are experiencing, but also how intense or severe the impact of the identified problem is on the overall food security and nutrition status. This knowledge will influence the nature, extent and urgency of the assistance needed by affected population groups. Different scales or phases to grade or classify food security have been developed by food security analysts using different indicators and cut-off points or benchmarks. Examples include: Measuring the Severity of Undernourishment The measure for hunger compiled by FAO, defined as undernourishment, refers to the proportion of the population whose dietary energy consumption is less than a pre-determined threshold. This threshold is country specific and is measured in terms of the number of kilocalories required to conduct sedentary or light activities. The undernourished are also referred to as suffering from food deprivation.

Box 2. Analyzing the Risk of Becoming Food Insecure For example, we may be interested in analyzing the risk of becoming food insecure as a result of a flood. If a household lives outside a flood plain then the exposure to flooding is low and therefore the risk of a flood causing the household to become food insecure is

An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security

low (unless their crops are in the valley!).

Food Security Information for Action

Practical Guides

However, if they live on the flood plain, but they have the ability to cope with the hazard, for example by being very mobile, and being able to move their animals and/or food crops to safety, then the risk may still be low.

deprivation that relate to human capabilities including consumption and food security, health, education, rights, voice, security, dignity and decent work.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

V. HUNGER, MALNUTRITION AND POVERTY It is important to understand how these three concepts are related to food insecurity.

Hunger is usually understood as an uncomfortable or

It is argued that a strategy for attacking poverty in conjunction with policies to ensure food security offers the best hope of swiftly reducing mass poverty and hunger. However, recent studies show that economic growth alone will not take care of the problem of food security. What is needed is a combination of: - income growth; supported by - direct nutrition interventions; and - investment in health, water and education. FIND OUT MORE:

E-learning

These guidelines are taken from the e-learning course Food Security Concepts and Frameworks available at: www.foodsec.org/dl

painful sensation caused by insufficient food energy consumption. Scientifically, hunger is referred to as food deprivation. Simply put, all hungry people are food insecure, but not all food insecure people are hungry, as there are other causes of food insecurity, including those due to poor intake of micro-nutrients.

Malnutrition results from deficiencies, excesses or

imbalances in the consumption of macro- and/or micronutrients. Malnutrition may be an outcome of food insecurity, or it may relate to non-food factors, such as: - inadequate care practices for children, - insufficient health services; and - an unhealthy environment. While poverty is undoubtedly a cause of hunger, lack of adequate and proper nutrition itself is an underlying cause of poverty. A current and widely used definition of poverty is: Poverty encompasses different dimensions of

Further Reading

Devereux, S. 2006 Distinguishing between chronic and transitory food insecurity in emergency needs assessments. SENAC. WFP. Rome. Dilley M. and Boudreau T.E. Coming to terms with vulnerability: a critique of the food security definition. Food Policy, Volume 26, Number 3, June 2001 , pp. 229-247(19) FAO. 2003. Focus on Food Insecurity and Vulnerability A review of the UN System Common Country Assessments and World Bank Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers. FIVIMS Secretariat and Wageningen University and Research Centre: www.fao.org/DOCREP/006/Y5095E/Y5095E00.htm Sen, A.K. 1981. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlements and Deprivation. Oxford. Clarendon Press. Stamoulis, K. and Zezza, A. 2003. A Conceptual Framework for National Agricultural, Rural Development, and Food Security Strategies and Policies. ESA Working Paper No. 03-17, November 2003. Agricultural and Development Economics Division, FAO, Rome. www.fao.org/documents/show_cdr. asp?url_file=/docrep/007/ae050e/ae050e00.htm WFP.2005. Emergency Food Security Assessment Handbook. http://www.wfp.org/operations/emergency_needs/EFSA_ section1.pdf

Figure 1: Food insecurity, malnutrition and poverty are deeply interrelated phenomena Poverty

Low productivity

Food insecurity, hunger and malnutrition

This document is available online at: www.foodsec.org/docs/concepts_guide.pdf For more resources see: http://www.foodsec.org/pubs.htm FAO 2008 Published by the EC - FAO Food Security Programme website: www.foodsec.org e-mail: information-for-action@fao.org

Poor physical and cognitive development

You might also like

- Regional Overview of Food Insecurity. Asia and the PacificFrom EverandRegional Overview of Food Insecurity. Asia and the PacificNo ratings yet

- Lesson 13 SUSTAINABLE WORLD SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENTDocument31 pagesLesson 13 SUSTAINABLE WORLD SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENTyamizenaku04No ratings yet

- Contemp ExpalinDocument8 pagesContemp ExpalinEka MagsigayNo ratings yet

- PPH 324 Lecture 1Document5 pagesPPH 324 Lecture 1KendiNo ratings yet

- 4 5861665975673294635Document17 pages4 5861665975673294635Asnake YohanisNo ratings yet

- Hunger Malnutrition and PovertyyyDocument22 pagesHunger Malnutrition and PovertyyyEnzoNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Food InsecurityDocument10 pagesModule 6 Food InsecurityNizea Camille Navarro JavierNo ratings yet

- Food Insecurity Duration: 6 HoursDocument13 pagesFood Insecurity Duration: 6 HoursLeila Mae L. InfanteNo ratings yet

- Food Security: A PrimerDocument4 pagesFood Security: A PrimerjournalNo ratings yet

- FOOD INSECURITY GUIDEDocument7 pagesFOOD INSECURITY GUIDEJustine Ivan CapiralNo ratings yet

- Global Food SecurityDocument5 pagesGlobal Food SecurityJhomer MandrillaNo ratings yet

- An Assignmennt On Food SecurityDocument16 pagesAn Assignmennt On Food SecuritySamira RahmanNo ratings yet

- Learner Notes 0411Document14 pagesLearner Notes 0411Mohamed AbdiNo ratings yet

- Farm LawDocument14 pagesFarm LawDEEPALI KATIYARNo ratings yet

- Food Security Final ReportDocument28 pagesFood Security Final ReportAqsa SarfarazNo ratings yet

- Global Food SecurityDocument11 pagesGlobal Food SecurityMarjorie O. Malinao100% (1)

- Food Security: Meaning and ImportanceDocument4 pagesFood Security: Meaning and ImportanceNitish Thakur100% (1)

- Socio-Economic Determinants of Household Food Insecurity in PakistanDocument22 pagesSocio-Economic Determinants of Household Food Insecurity in PakistanAmit YadavNo ratings yet

- Foods: Food Security-A Commentary: What Is It and Why Is It So Complicated?Document10 pagesFoods: Food Security-A Commentary: What Is It and Why Is It So Complicated?Nia HumairaNo ratings yet

- Ghattas Food Security and Nutrition PDFDocument18 pagesGhattas Food Security and Nutrition PDFRohmatul Bariroh Al FaiqohNo ratings yet

- Report Global Food SecurityDocument3 pagesReport Global Food SecurityK8Y KattNo ratings yet

- Food SecurityDocument11 pagesFood SecurityJanedyl Mando Salvador100% (1)

- food securityDocument6 pagesfood securityRiya PandeyNo ratings yet

- Environmental Studies.: End Hunger and Achieve Food SecurityDocument20 pagesEnvironmental Studies.: End Hunger and Achieve Food SecurityRishita JalanNo ratings yet

- Food Security: Hunger StarvationDocument15 pagesFood Security: Hunger StarvationhanumanthaiahgowdaNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status of Children in Fisherfolk HouseholdsDocument6 pagesNutritional Status of Children in Fisherfolk HouseholdsSofia IntingNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status and Food SecurityDocument12 pagesNutritional Status and Food SecurityCaurrine MonsaludNo ratings yet

- The Different Food SystemsDocument3 pagesThe Different Food SystemsAnie Faye AribuaboNo ratings yet

- FP Lecture 2-4 2020Document15 pagesFP Lecture 2-4 2020Richard Simon KisituNo ratings yet

- FINAL REPORT Food SecurityDocument23 pagesFINAL REPORT Food SecurityAbinash KansalNo ratings yet

- Week 16 Global Food SecurityDocument5 pagesWeek 16 Global Food Securitydonnasison0929No ratings yet

- FNS eDocument71 pagesFNS eRaaz The ghostNo ratings yet

- Food SecurityDocument6 pagesFood SecurityYukta PatilNo ratings yet

- Global Food SecurityDocument25 pagesGlobal Food SecurityMelanie JulianesNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 FSQCDocument28 pagesUnit 4 FSQCvaralakshmi KNo ratings yet

- Food SecurityDocument10 pagesFood SecurityKids Learning R.BNo ratings yet

- Food InsecurityDocument4 pagesFood InsecurityElisa WintaNo ratings yet

- ALEMUDocument18 pagesALEMUtamirat zemenu100% (1)

- The COVID-19 Nutrition Crisis:: What To Expect and How To ProtectDocument4 pagesThe COVID-19 Nutrition Crisis:: What To Expect and How To Protectvipin kumarNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 Agriculture Science Week 4 Lesson 2Document15 pagesGrade 10 Agriculture Science Week 4 Lesson 2NesiaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Food SecurityDocument5 pagesThesis Food Securityafibybflnwowtr100% (2)

- What Are We Assessing When We Measure Food Security? A Compendium and Review of Current MetricsDocument25 pagesWhat Are We Assessing When We Measure Food Security? A Compendium and Review of Current MetricszamanraiNo ratings yet

- Farmers Viewpoint On Food SecurityDocument9 pagesFarmers Viewpoint On Food SecurityLeonardo MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Food SecurityDocument2 pagesFood SecurityZahid GujjarNo ratings yet

- Food Security: A Human RightDocument6 pagesFood Security: A Human RightDoan Yen-NgocNo ratings yet

- 7Document10 pages7dyz2nybk8zNo ratings yet

- Food Safety FAO PaperDocument2 pagesFood Safety FAO PaperKathiravan GopalanNo ratings yet

- Nutrition in Emergencies Strategy GuideDocument8 pagesNutrition in Emergencies Strategy Guidehyperlycan5No ratings yet

- HTP Module 1 Fact SheetDocument5 pagesHTP Module 1 Fact SheetMoses JoshuaNo ratings yet

- Global Food SecurityDocument7 pagesGlobal Food SecurityMizraim EmuslanNo ratings yet

- Food Security Related ThesisDocument4 pagesFood Security Related Thesismichelethomasreno100% (2)

- Food Security: Definition, Four Dimensions, HistoryDocument28 pagesFood Security: Definition, Four Dimensions, HistoryzorelNo ratings yet

- CFS OEWG MYPoW 2016 03-18-02 HLPE Note Emerging IssuesDocument26 pagesCFS OEWG MYPoW 2016 03-18-02 HLPE Note Emerging Issuespash blessingsNo ratings yet

- Hunger Alleviation & Nutrition Landscape AnalysisDocument82 pagesHunger Alleviation & Nutrition Landscape AnalysisthousanddaysNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Food Insecurity and TheDocument15 pagesDeterminants of Food Insecurity and TheFirafir FirafirNo ratings yet

- SUMMARY FSN Difference & Problem PDFDocument5 pagesSUMMARY FSN Difference & Problem PDFKarthick KumaravelNo ratings yet

- Food and Nutrition: Matters of Public Health: Imedpub JournalsDocument3 pagesFood and Nutrition: Matters of Public Health: Imedpub JournalsAhmad IsmadiNo ratings yet

- Nutrition SecurityDocument21 pagesNutrition SecuritySakshi RaiNo ratings yet

- Food SecurityDocument2 pagesFood SecurityJaymar ConsultaNo ratings yet

- 321 E Lesson 1Document15 pages321 E Lesson 1Kiran GrgNo ratings yet

- Lifestyle WA Q1 16 WebDocument24 pagesLifestyle WA Q1 16 WebPrince GodswillNo ratings yet

- Calcium Lactate Gluconate Aug02Document3 pagesCalcium Lactate Gluconate Aug02tarekscribdNo ratings yet

- Sports and fitness vocabulary and grammarDocument14 pagesSports and fitness vocabulary and grammarZuats100% (1)

- CNCC-1: Certificate in Nutrition and Child Care (CNCC) Term-End Examination December, 2019Document12 pagesCNCC-1: Certificate in Nutrition and Child Care (CNCC) Term-End Examination December, 2019Rohit GhuseNo ratings yet

- Nutrition in PlantsDocument8 pagesNutrition in PlantsSweet HomeNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Final Print-Ready April 2011Document207 pagesNutrition Final Print-Ready April 2011jrence100% (1)

- Food DiaryDocument14 pagesFood Diaryandreea.mitroescuNo ratings yet

- Hea - Lthy Hab - Its Quiz: Do You ..Document7 pagesHea - Lthy Hab - Its Quiz: Do You ..2C50Serly SeptiyantiD3 GIZINo ratings yet

- Session 9Document27 pagesSession 9Quang Minh TrầnNo ratings yet

- C-NATTOLIN CatalogueDocument6 pagesC-NATTOLIN CatalogueFroggiesNo ratings yet

- Brie - Google SearchDocument1 pageBrie - Google SearchPuthiroth Kim 9ENo ratings yet

- Effect of Multigrain Soya Panjiri Supplementation On Quetelet Index and Anaemia Profile of Malnourished Women of ChhattisgarhDocument4 pagesEffect of Multigrain Soya Panjiri Supplementation On Quetelet Index and Anaemia Profile of Malnourished Women of ChhattisgarhIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Unit 10Document7 pagesUnit 10Minh Đức NghiêmNo ratings yet

- Community Based Management of Acute MalnutritionDocument149 pagesCommunity Based Management of Acute MalnutritionGirma Goshime100% (2)

- NETA GX Study Guide Schedule Aug 2014Document4 pagesNETA GX Study Guide Schedule Aug 2014powerliftermiloNo ratings yet

- Lab Report: Calculating Energy Content of Foods With A CalorimeterDocument5 pagesLab Report: Calculating Energy Content of Foods With A CalorimeterLyzette RiveraNo ratings yet

- Fructooligosaccharide: I. Structure of The BiomoleculeDocument2 pagesFructooligosaccharide: I. Structure of The BiomoleculechogabykyuNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Management of The Burn Patient: MicronutrientsDocument4 pagesNutritional Management of The Burn Patient: MicronutrientsGina KatyanaNo ratings yet

- Ic Presentation 1Document11 pagesIc Presentation 1api-304006337No ratings yet

- Kristina Saha Mintel and SimmonsDocument16 pagesKristina Saha Mintel and SimmonsKristina SahaNo ratings yet

- Physical Education 11: Fitness Enhancement Through Physical ActivitiesDocument15 pagesPhysical Education 11: Fitness Enhancement Through Physical ActivitiesEdmark Luspe82% (11)

- Forms For Monthly ReportDocument10 pagesForms For Monthly ReportHanz HernandezNo ratings yet

- Lactose CRINO v. 19A-0201 WyDocument1 pageLactose CRINO v. 19A-0201 WyPedro Velasquez ChiletNo ratings yet

- 1 IntroductionDocument11 pages1 Introductionjvr341138No ratings yet

- Caroline O'Mahony Caroline's Fit PlanDocument30 pagesCaroline O'Mahony Caroline's Fit PlanGizem MutluNo ratings yet

- Industry Workshop Component-3Document16 pagesIndustry Workshop Component-3Aneesha GuptaNo ratings yet

- Biological KingdomsDocument2 pagesBiological KingdomsValeria GrijalvaNo ratings yet

- How To Boost Your Metabolism and Burn More FatDocument2 pagesHow To Boost Your Metabolism and Burn More FatMirzaNo ratings yet

- 2,800-Calorie Sample Meal PlansDocument2 pages2,800-Calorie Sample Meal PlansOleksandr FurmanNo ratings yet