Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Classics of Political Theory

Uploaded by

MichaelOB83Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Classics of Political Theory

Uploaded by

MichaelOB83Copyright:

Available Formats

9/29/12

Classics of political theory

essaybank.degree-essays.com

http://essaybank.degree-essays.com/philosophy/classics-ofpolitical-theory.php

Classics of political theory

In what follows, I critically evaluate Hobbes' arguments against the 'fool's claims, as presented in the Leviathan. Hobbes' 'fool' is an imaginary being who believes Justice i.e. honoring one's covenants, sometimes may be an irrational action, or one not conducive to furthering one's self interest (Cahn 409R). I will defend Hobbes' arguments and consequently defend the 'keeping of covenants' as a Law of Nature that follows from rationality. Given my acceptance of Hobbes' arguments as sufficient evidence against the fool's claims, I will be, in essence, defending Hobbes' derivation of morality from enlightened self-interest. Before I delve into Hobbes' arguments, I must state the fool's position as plainly as possible. Hobbes' fool's primary belief is that each individual should act in a way that furthers their own self-interest. The end in mind of any rational individual is that of self preservation. But, the fool proclaims that it is not guaranteed that the keeping of a particular covenant will lead to self preservation (Cahn 410L). In fact, the fool believes it to be possible that a covenant may directly interfere with one's self interest. When such a conflict arises, between an individual's self interest and a covenant, the fool believes it is necessary to "make or break, keep or not keep covenants...when it conduced to one's benefits (Cahn 410L)." Thus, the fool claims that Justice i.e. the keeping of covenants may conflict with one's self preservation. Here, it is essential to define Hobbesian morality as sustenance of Justice that allows for everyone's self preservation (Cahn 403R). Therefore, the assumption that the breaking of covenants, which Hobbes identifies as 'injustice,' could be in one's self interest clearly disrupts the Hobbesian link between enlightened self-interest and morality. Thus Hobbes, in his argument, must reconcile the Third Law of Nature; that of keeping covenants, with rational self interest at all times. Section (1) Hobbes' Arguments in Reply to the Fool

Hobbes' approach to the fool's claims is two pronged in nature. He first concedes that it may be beneficial for an individual to break a covenant at times (Cahn 410R). But, he believes that while it

1/5

9/29/12

Classics of political theory

may be beneficial it is never prudent, and therefore, not in a person's self interest (Cahn 410R). Hobbes elucidates this fact by highlighting the unpredictability of results of breaking a covenant. He explains that an individual may be in a situation where breaking a covenant would be beneficial to him, but by no means could an individual know for certain that he is in such a circumstance (Cahn 410R). Therefore, any time someone decides to break a covenant, there is a risk factor involved. Hence, Hobbes contends that the value of the judgment at that time depends not on the actual outcome but on the expected outcome. The risk may be very miniscule or non-existent but due to the unknown nature of the results, the individual would never be assured of a beneficial outcome, and would find it prudent to oblige to the covenant rather than break it. Hobbes' second phase of the argument is based on his analysis of the risks of breaking covenants. To understand this facet of his argument, we must consider first, the value Hobbes places on covenants as a means of preservation. He certainly believes that man cannot survive for long without covenants. Hobbes states this as, "There is no man who can by his own strength, or wit, defend himself from destruction, without the help of confederates... (Cahn 410R)." The confederates of course would emerge only through covenants. Therefore since covenants are so important, trustworthiness, reputation and the preservation of one's ability to form covenants can be viewed as an utmost necessity in society. Therefore, every time the fool violates a covenant, he runs the risk of being discovered and cast out of society. This risk, Hobbes believes, is sufficient to hinder one from attempting to benefit from breaking a covenant. Hence, as a general rule, Hobbes believes it is more prudent to follow the covenant than to evaluate the risks vs. rewards of breaking each specific covenant. Section (2) Critical Evaluation of Hobbes' Argument While analyzing Hobbes' first part of the argument i.e. that concerning the unpredictability of results, one may wonder if Hobbes has allowed for an obvious criticism. It seems very plausible that a situation may arise where an individual can see the benefits of breaking a covenant to vastly outweigh the costs and the risks. Here, the individual has maximized the probability of a favorable outcome and therefore, the risk or probability of an unfavorable outcome is negligible. An ideal example of such a circumstance is in the game of roulette. In order to maximize the likelihood of a favorable outcome, let us assume that there are a million chambers in the gun. One is then given the gun and must choose whether to pull the trigger or not. The possibility of landing the loaded chamber is .0001%. The possibility of winning (let us assume $100,000) is .9999%. Hobbes believes that in such a situation, where the chances of winning a 100,000 dollars are almost (but not fully) ensured, a man would choose not to pull the trigger for he values his life much more than any monetary sum. Placing a monetary sum above a man's life would mean that the individual is giving more credence to money than his law of nature; that of self-preservation (Cahn 400R). Hobbes believes that no rational being would ever do this. This game can in essence be seen as a

essay bank.degree-essay s.com/philosophy /classics-of -political-theory .php 2/5

9/29/12

Classics of political theory

metaphor for covenant keeping. Pulling the trigger represents breaking the covenant. The risk of being discovered as one who breaks covenants leads to an inability to make covenants in the future and consequently an inability to preserve oneself. Therefore landing the loaded chamber, i.e. certain death, can be understood as risking being discovered in Hobbes' world. Hobbes believes that the individual would most certainly never try to injure his self interest or the ends of self preservation, just as a rational being would never pull the trigger. One of the biggest challenges to Hobbes' argument lies in the presence of a silent fool, or as I will call him; an opaque predator. Hobbes' argument, thus far holds strong when faced with a vocal fool or a transparent predator i.e. one who allows it to be known in society that he plans to be breaking a covenant. Such men will simply be punished by the sovereign or be cast away by society as men unfit to covenant with. But, an opaque predator or a man who pretends to keep the covenant but secretly breaks it whenever breaking it furthers his self interest or maximizes his utility, poses a great challenge to Hobbes' defense of morality resulting from rational self interest. This opaque predator can therefore, one may argue, maximize his utility in every circumstance. Hobbes agrees with the ethical egoism that drives the actions of the opaque predator. Nevertheless, Hobbesian philosophy does not permit self interest to be amoral i.e. the breaking of covenants to be in one's self interest. Therefore, Hobbes does not agree that the strategy of being an opaque predator serves one's long term rationality better than adhering to the third law of nature. The basis of his defense to the 'opaque predator' lies in the belief, though not explicitly stated, that no one can truly be an opaque predator indefinitely. One must first note that new covenants for mutual self interests and preservation need to be created rather frequently through life. This phenomenon can best be understood in terms of game theory and the two prisoner dilemma game. Hobbes believes that the best interest of both prisoners would be served by cooperating with each other and receiving equal sentences. But, both prisoners are aware that if one of them defects and the other cooperates then the defector's prison term is shortened by a substantial amount. An opaque predator in such a situation would simply defect and get the shorter term. Though he runs the risk of getting a longer term if both prisoners defect, he is fairly sure that the other will keep his covenant and cooperate. But if one wants to portray the prisoner dilemma game as the truest metaphor of a Hobbesian society, it is necessary to repeat this game indefinitely between the same two prisoners. This repetition is symbolic of the covenants as they are usually long lasting, or made frequently in society amongst people, and mutual trust is vital for the formation of these covenants. In this case both the prisoners will do better collectively as well as individually, by cooperating rather than defecting. It must be noted that each prisoner's present choices will affect the other prisoner's future choices. Such is the nature of covenants in society. If a man is found to be a covenant breaker, though he may have benefitted from the previous covenant, he will face a grave challenge in forming new covenants with people. The mistrust and loss of repute in the fool

essay bank.degree-essay s.com/philosophy /classics-of -political-theory .php 3/5

9/29/12

Classics of political theory

would outweigh any benefits that the fool may have enjoyed by breaking the covenants. Therefore Hobbes' contention that it would be in one's self interest to oblige to covenants all the time holds true. The aforementioned scenario takes one crucial aspect for granted; the predator is opaque for only one covenant. Now, let us imagine an opaque predator that does not let his intentions be known to society (at least not willfully). Now we have a silent fool who can actually trick people into thinking he has maintained his covenants even when he breaks them. Here too, Hobbes' link between enlightened self interest, keeping covenants, Justice and morality is maintained. But to understand this example we must seek examples from the real world. The present day opaque predators would be the mafia or gangsters who manage to exploit society's many covenants, for definite periods of time, to maximize their utility. But the qualification that these gangsters and criminals can only live as opaque predators for specific periods leads to Hobbes' defense. They cannot continue to dupe society indefinitely. Example: the biggest criminals and crooks such as Al Capone, John Gotti or Barney Frank have inevitable been caught and imprisoned. In Hobbesian society this can be seen as being shunned from society or punished by the sovereign. The reason Hobbes would dictate that these 'temporarily' opaque predators do not further their self interest by breaking the covenants is that once they do break the covenants, they enter a society of social deviants where they have to constantly fear punishment or retribution; from the sovereign or even from other temporarily opaque predators with whom they now live in a Hobbesian state of war. But since Hobbes contends that at times it may be beneficial to break a covenant and further one's self interest, let us imagine an indefinitely opaque predator. This opaque predator will in essence maximize his utility for his entire life, and for every covenant that he has formed (and broken). But, Hobbes qualifies that this fool would never truly know when he is in such a situation where breaking a covenant would be to his advantage and where the risk of being discovered would be negligible. Even if a fool does know this for one covenant, he cannot possibly ascertain the outcome every time he breaks the covenant. Therefore, Hobbes believes that the expected outcome, even for an indefinitely opaque predator cannot be one that furthers his self interest. Though the actual outcome in this case would be beneficial to the fool, the expected outcome in each case will invariably be against him. Therein lays Hobbes' defense against the indefinitely opaque predator. As a general rule, even the opaque predator is better off following the covenant than deciding to keep or not keep the covenant on a situational basis. As mentioned above, Hobbes argument against the fool holds true; that in every situation it would further one's self interest by following the covenant. This subsequently allows for the dismissal of the fool's claims that there is no justice. Additionally, since justice and self interest can be reconciled, as can morality; which is the sustenance of justice, be derived from rational self interest.

essay bank.degree-essay s.com/philosophy /classics-of -political-theory .php 4/5

9/29/12

Classics of political theory

References

1. Cahn Steven.Classics of Political and Moral Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

essay bank.degree-essay s.com/philosophy /classics-of -political-theory .php

5/5

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Durkheim and WeberDocument21 pagesDurkheim and Weberriya.2021.212No ratings yet

- 1.2 f10167 Randall Collins FragmentDocument24 pages1.2 f10167 Randall Collins FragmentAndreea MarilenaNo ratings yet

- GVDB - Future of Theology in AcademicsDocument9 pagesGVDB - Future of Theology in AcademicsJan Maarten HeldoornNo ratings yet

- 1994 - Roche - Mega-Events and Urban PolicyDocument19 pages1994 - Roche - Mega-Events and Urban PolicyJulia GCNo ratings yet

- Yasenik and Gardner - Play Therapy Dimensions Model - Chapter 1Document24 pagesYasenik and Gardner - Play Therapy Dimensions Model - Chapter 1artemidi100% (2)

- Anthony Dunne - Hertzian Tales - Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience, and Critical Design-The MIT Press (2006) PDFDocument193 pagesAnthony Dunne - Hertzian Tales - Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience, and Critical Design-The MIT Press (2006) PDFIhjaskjhdNo ratings yet

- Legal Technique and LogicDocument16 pagesLegal Technique and LogicrealestateparanaqueNo ratings yet

- A2 (Decsion Making) 700 WordsDocument6 pagesA2 (Decsion Making) 700 WordsSadiaNo ratings yet

- The Yoruba EthicsDocument25 pagesThe Yoruba EthicsBalogun JosephNo ratings yet

- 06-When The Supply Side of A Management Accounting Innovation Fails - The Case of Beyond BudgetinDocument37 pages06-When The Supply Side of A Management Accounting Innovation Fails - The Case of Beyond BudgetinDino SmajićNo ratings yet

- Fainstein-Planning Theory and The CityDocument11 pagesFainstein-Planning Theory and The CityMarbruno HabybieNo ratings yet

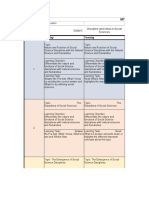

- DISS Philo-Learning-Plan-TeachersDocument42 pagesDISS Philo-Learning-Plan-TeachersJeryn Ritz Mara HeramizNo ratings yet

- 1 Reviewerprelim ETHICSDocument5 pages1 Reviewerprelim ETHICSReniel MillarNo ratings yet

- The Civic Conversations of Thucydides and Plato Classical Political Philosophy and The Limits of Democracy in Tucidides PDFDocument340 pagesThe Civic Conversations of Thucydides and Plato Classical Political Philosophy and The Limits of Democracy in Tucidides PDFbengratefulNo ratings yet

- Psychology and Constructivism in International RelationsDocument288 pagesPsychology and Constructivism in International RelationsJon100% (2)

- Stalnaker 1976 PropositionsDocument13 pagesStalnaker 1976 PropositionscbrincusNo ratings yet

- Hartmut Kliemt - Philosophy and Economics Vol.1Document164 pagesHartmut Kliemt - Philosophy and Economics Vol.1wij060788No ratings yet

- Talcott Parsons July 2017Document41 pagesTalcott Parsons July 2017anupsingh775100% (1)

- MGMT 405 Chapters 7, 8 & 9 AnnotationsDocument15 pagesMGMT 405 Chapters 7, 8 & 9 AnnotationskevingpinoyNo ratings yet

- Kurt Weyland - Assault On Democracy - Communism, Fascism, and Authoritarianism During The Interwar Years-Cambridge University Press (2021)Document399 pagesKurt Weyland - Assault On Democracy - Communism, Fascism, and Authoritarianism During The Interwar Years-Cambridge University Press (2021)Tietri Santos Clemente Filho100% (1)

- Interorganizational Trust in B2B Relationships: Carol Saunders, Yu "Andy" Wu, Yuzhu Li, Shawn WeisfeldDocument8 pagesInterorganizational Trust in B2B Relationships: Carol Saunders, Yu "Andy" Wu, Yuzhu Li, Shawn WeisfeldRashmeen NarangNo ratings yet

- The Other Side of Language A Philosophy of ListeningDocument31 pagesThe Other Side of Language A Philosophy of ListeningCarolina40% (5)

- Introduction To Artificial Intelligence Cosc 4061: Chapter OneDocument64 pagesIntroduction To Artificial Intelligence Cosc 4061: Chapter OneTadesse BitewNo ratings yet

- Incomplete Contracts and Economic Organization - FOSSDocument48 pagesIncomplete Contracts and Economic Organization - FOSSAndre VianaNo ratings yet

- J.M. Coetzee's exploration of revelation in Musil's short storiesDocument6 pagesJ.M. Coetzee's exploration of revelation in Musil's short storiesMarius DomnicaNo ratings yet

- Diss q1 m5 Ver2 FinalDocument16 pagesDiss q1 m5 Ver2 FinalDale CalicaNo ratings yet

- IBANDA UNIVERSITY SOCIAL WORK THEORY COURSEDocument10 pagesIBANDA UNIVERSITY SOCIAL WORK THEORY COURSEBonane AgnesNo ratings yet

- DesignScience DSDocument25 pagesDesignScience DSAnonymous txyvmbYNo ratings yet

- General Plan Evaluation CriteriaDocument14 pagesGeneral Plan Evaluation CriteriaInertia Indi HapsariNo ratings yet

- BD 2-Herrmann-E-BookDocument346 pagesBD 2-Herrmann-E-BookPeter HerrmannNo ratings yet