Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Parlia vs. Democracy

Uploaded by

Xymon BassigOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Parlia vs. Democracy

Uploaded by

Xymon BassigCopyright:

Available Formats

Dr. Courtney Brown Developmental Democracy Some Past Test Questions 1.

List and explain Richard Joseph's eight phases of transition to democracy that were outlined in class. Explain with examples how a country can experience these phases sequentially (i.e., one after the other), or simultaneously (one or more phases at the same time). 2. According to Robert Dahl, what is polyarchy, and what are the seven most important procedural minimums that are required in order to make democracy possible? If these procedures are required, describe and explain some (minimally three) things about which there can be great variation in democratic structure (e.g., the types of institutions that are established). 3. Samuel P. Huntington lists five major factors that have contributed to the occurrence and timing of the most recent wave of transitions to democracy. Two of these factors are changes in the role of external actors (such as United States and the Soviet Union) and snowballing. Explain these things. When a nation reverts to authoritarian rule (as in the case of Nigeria), Huntington argues that certain factors are responsible. List at least four of these factors and explain them. 4. What are the three paradoxes of democracy that are identified by Larry Diamond? Explain them. How is federalism sometimes used to manage democratic systems that govern societies with deep ethnic cleavages (i.e., divisions)? 5. Using Nigeria as your primary example, discuss the problem of corruption in states wanting to experiment with democracy. What are various strategies that have been suggested in our text for reforming corruption. Would they work in Nigeria? Why or why not? Include in your discussion insights involving corruption that you have gained from Ali Mazrui's video presentation, "New Conflicts." 6. Why has it been so difficult for newly independent African states to develop stable democratic institutions that parallel the governments of their European and American counterparts? Ali Mazrui's insights on this matter (from his Search for Stability" presentation) would be useful to blend into your answer. But also, what is prebendalism and why has it developed into a African governmental form? Connect this to the first part of your answer. 7. What is Down's economic theory of democracy? Explain it using both words and pictures. Then, clearly explain how this theory applies to problems of democratization in developing nations. Give examples to illustrate your points. 8. Describe the complexities of the problems of national debt and foreign aid with regard to new democracies in Africa. Why is the U.S. and other Western powers giving little attention to

African democracies? Where is the attention going and why? Why are South American democracies apparently working while African democracies are having real troubles. There are lots of political consequences and intricacies related to these things. Talk about all of them. 9. Describe a single detailed but general (i.e., applicable to many countries) model of the sources and consequences of the scarcity of renewable resources that includes ideas such as unequal resource access and weakened states. Draw a diagram of the model and explain it with words. Then relate this model to the idea of developmental democracy. How do these ideas relate to an authoritarian government that may be in a transition to democracy, and visa versa? Give examples that address the concept of carrying capacity. 10. Give three models of the role that the scarcity of renewable resources plays in the emergence of violent conflict within a country. Describe also how these three models typically happen sequentially (i.e., over time, one after the other). Draw a diagram of each model, and explain them with words. Then carefully describe how a developing country may be helped or hindered in its movement toward a democratic transition due to these environmental problems. Examples are wonderful, and needed. 11. Describe a model that explains the eruption of internal violence, both urban and rural, in the Philippines that has environmental degradation as one of its primary causes. Give a pictorial representation of the model as well as a verbal description. Tell how democracy and the environment in the Philippines interact and are interdependent. 12. Following Sprague, how does voter institutionalization relate to electoral system bias? Why is this important for developing countries who have just initiated democratic government? How does winner take all vs. proportional representation systems relate to this? 13. What is political corruption? How is it relative to a society? Give examples of corruption that can destabilize a democratic regime and other examples that may not hurt. Explain the "why" for each. What is a form of governance in which corruption is an integral and useful aspect? What should the trend of political corruption look like with regard to political decay and democratic transition? What warning signs need to be heeded in this regard? 14. What are the some of the potential problems with proportional representation systems with regard to democracy in developing countries? Give examples. Be specific. 15. Describe the role that culture plays in democratic development. Give examples from across the globe to illustrate your points. 16. What are the arguments in favor of a parliamentary system of government in a setting in which a nation has a developing democracy? What problems could a presidential system bring to

the situation? Under what social conditions within a country could a presidential system help rather than hurt the stabilization of the country's democratic political future? Again, give some examples. 17. Describe Ali Mazrui's ideas (from his video "In Search of Stability") of how developing countries may successfully conduct democratic elections in Africa, only to have the military execute a coup that destroys the democratic process. What was wrong with the democratic situation such that this is such a common occurrence? How does this relate to traditional sources of authority and governance in Africa? 18. What are the factors that can cause a newly formed democracy to collapse into authoritarianism, i.e., to experience a retreat from democracy? Explain the factors, with examples. With this in mind, explain why India is still democratic. 19. Speaking on the subject of democracy and federalism in Africa, consider the following words of Leopold S. Senghor, the former president of Senegal. Our Democracy will be federal. Local differences, being complementary to each other, will enrich the Federation and, conversely, the Federation will preserve the differences. Let us take the idea a little further. The federal structure . . . within the framework of the Federal State itself, to regional and communal collectivities even in social and economic matters. The Yugoslav structures adapted to our own situation can be used at this juncture as models. Use your own understanding of federalism to explain, justify, or critique Senghor's views. What does federalism do specifically to which Senghor may be referring? Explain why his analogy to Yugoslavia ultimately failed. Does this mean federalism in African will fail? Explain. 20. Put developmental democracy into a "macro" or wide-angle perspective. From a Western perspective, why is the development of democracy within a society an "natural" occurrence? In particular, describe the attributes of social and political evolution relating to change that have been identified by Nisbet. List and describe four dichotomous schemes for looking at political modernization. What do these schemes have to do how we conceptualize political modernization? 21. List and describe four crises of development that all societies may go through while they evolve in the direction of developmental democracy. Explain these crises. How are they related to Nisbet's uniform causes of social change? 22. Explain Adam Przeworski's theory of de-institutionalization as the source of political instability.

23. Discuss Angola's difficult transition to democracy, as presented by Marina Ottoway in Kumar's book. What went wrong, and what lessons have we learned from this case? 24. List and explain Lucian Pye's five crises of political development. How does Huntington's desire to insure political order and stability relate to Pye's ideas. Be sure to explain Huntington's ideas regarding this as well. 25. What are "easy" and "hard" issues, and what relevance do they have for developmental democracy? How does this relate to concepts of governmental structures, such as federalism? How do these two types of issues relate to governmental stability in a developing society? 26. What is Down's economic theory of democracy? Explain it using both words and pictures. Then, clearly explain how this theory applies to problems of democratization in developing nations. How does environmental decay enter into the problem of creating democratic stability given the ideas of Down's macro perspective? Give examples to illustrate your points. 27. Explain Adam Przeworski's theory of de-institutionalization as the source of political instability. How do Przeworski's ideas compare with those of Huntington? 28. From Kumar, what are postconflict elections? What are the objectives of postconflict elections? What are the impediments to postconflict elections? Identify and describe three roles that the international community can play in post conflict elections. 29. From Dahl, identify and explain the three possible paths that can lead to the development of a democratic culture. Also, how does this relate to the development of democracy in China? Which path is most relevant to China and why? 30. List and explain Lucian Pye's five crises of political development. What are Organskis stages of political growth? How do Pyes crises relate to Organskis stages of political growth? Finally, describe how Huntington's desire to insure political order and stability relate to Pye's ideas. Be sure to explain Huntington's ideas regarding this as well. 31. Describe Liberias experience with democracy, from the prelude to the 1997 elections to the current time. How does the Liberian situation relate to Richard Josephs ideas regarding the steps needed for a democratic transition? Is prebendalism relevant here, and if so, how? Explain. 32. What is the very general description of democracy that is offered by Phillip C. Schmitter and Terry Lynn Karl? With regard to this definition, define and explain the relevancy of (a) the public realm, (b) citizens, (c) competition and cooperation, (d) majority rule, and (e) representatives.

33. From the perspective of Ali Mazrui as portrayed in his video presentation In Search of Stability, why has it been so difficult for newly independent African states to develop stable democratic institutions that parallel the governments of their European and American counterparts? How does this connect with Dahls concept of polyarchy? Be complete in your answer, and give examples. 34. What is a mixed electoral system? Explain how this system differs from a strict proportional representational system and a single member plurality system. Describe Germanys use of this system, as well as some of the variations from Germanys usage that have been applied in other countries. 35. What is a single member plurality electoral system? Identify some countries that use such a system. What are some of the advantages of this type of electoral system? What are some of the disadvantages of this type of system? Why might such a system be useful or harmful to a new democratic state? Be specific, and give examples. 36. List and explain Lucian Pye's five crises of political development. Relate this to the stages of economic growth as described by W.W. Rustow as well as the stages of political growth as described by A.F.K. Organski. 37. How does Samuel Huntington's argument regarding the balance between political order and stability relate to the ideas regarding institutionalization made by Adam Przeworski?. Be sure to include a graph in your discussion of Huntington's ideas. 38. What are the five types of plurality-majority voting systems? What are semi-proportional electoral systems? What are proportional representation systems? What is preferential voting? Be sure to explain the variations in these voting systems, and offer examples of countries using these systems. 39. Why are deep ethnic cleavages difficult to manage in a new democracy? Describe various ways to address the problem of significant ethnic cleavages when setting up a new democracy. Give examples of countries in conflict in which these ideas are fully illustrated. Explain these examples.

PRESIDENTIALISM VS. PARLIAMENTARISM:

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE TRIAD OF MODERNITY By Fred W. Riggs

Note: This is a first draft. An abridged version has been published as "Presidentialism vs. Parliamentarism: Implications for Representativeness and Legitimacy," International Political Science Review. 18:3 (1998) pp.253-278.

PART ONE: MODERNITY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY

The collapse of the world's great modern empires -- both communist and capitalist in ideology -gave birth to a large number of successor states. Despite early optimism that they would soon become thriving democracies, many of them have become weak authoritarian states unable to govern effectively throughout their inherited domains. (Jackson. Quasi-States) In the anarchic chaos that prevails in many of these domains, rival ethnic groups and criminal gangs challenge the authority of those in power. Inherited colonial bureaucracies, headed by military officers, often respond to such crises by seizing power in order to impose peace and, of course, to protect their own rights and privileges.

1a. CONTEMPORARY CONTEXT

There are growing signs of democratization at work (Huntington, and Diamond, "Consolidation of Democracy") and a growing number of states have struggled out of turmoil and authoritarianism to establish (or re-establish) democratic constitutional government. What are the prospects for success of these emergent democracies? How can interested outsiders help the leaders of incipient democracies to succeed and to sustain their fledgling democratic institutions when they come under attack? To what extent is the fate of these countries determined by forces outside of their control? Could it be possible that if their leaders knew more about what works and what doesn't work in their situations, they would be able to make choices that would enhance the prospects for successful consolidation and maintenance of democratic institutions? More specifically, does it make a difference whether they choose to be governed by constitutional rules based on the separationof-powers as exemplified by the U.S. model, or by parliamentarism, based on the fusion-ofpowers as we find it in Western Europe?

I shall focus on some institutional variables that can be influenced by constitutional choices. No doubt many non- institutional forces, both domestic and external -- including economic development, cultural norms, geographic resources, and historical experiences are also fundamental and affect the prospects for democracy (Przeworski). However, it may be easier to change policies, laws, and even constitutional practices than to make fundamental changes in the non-institutional parameters. At least, we certainly need to add analysis of institutional variables to the information about non-institutional factors that has already received a good deal of attention. Because the basic design of any constitutional system of governance affects how many other institutional variables work, I shall focus on the pro's and con's of parliamentarism and presidentialism as they affect the capacity of any regime to cope with the fundamental problems generated by modernity, and what I see as its most important aspects: industrialism, nationalism and democracy. Let us first try to clarify the basic structural features of all modern organizations, including states, and then consider the triad of modernity. This foundation will enable us, subsequently, to look at the way different institutional patterns affect the capacity of contemporary states to deal with their most important modern problems.

1b. MODERN ORGANIZATIONS

What I see as the quintessential development that marks modern governance (both in states and in non-state organizations) is the structural linkage between two major components that take the form of (1), a constitutive system anchored in an elected assembly1 and (2), a managerial (bureaucratic) sub- system responsible for implementing the policies authorized by the constitutive system. Modern democracies (and, indeed, all modern associations -- i.e. selfgoverning organizations) link a constitutive system with a bureaucracy as symbolized by the yinyang symbol of Chinese classic philosophy (Riggs 1996a). The first component is polyarchic or representative -- its constituents (citizens, members) of any modern organization are formally represented in elected assemblies, and its head is also elected. The second component is hierarchic or managerial in which authority from above permeates the whole -- this is, of course, the main form of "traditional" or "pre-modern" governance, usually thought of as monarchic. Its legitimacy derived from supernatural forces that, as influenced by royal ceremonies and sacrifices, were thought to bring welfare and health to all subjects. In its evolved forms, monarchic rule was reinforced by bureaucratic structures of public administration that enabled rulers to dominate a population and extract the resources --financial, military, and spiritual -- that it needed to maintain its power. A few monarchies survive where these structures of authority persist - - they are contemporary but not modern in their constitutional structure.

Democratic (polyarchic) forms of governance also existed in pre- modern societies, but normally only on a small scale and, we may assume, all food-gathering (primitive) societies were organized polyarchically for many millennia before states were born. They still survive in contemporary stateless societies on the fringes of the modern world -- especially among some "indigenous" peoples. Although various intermediate stages that linked the polyarchic and hierarchic principles of organization can be found in pre-modern societies, the elaboration and formal institutionalization of the compound format (constitutive system plus bureaucracy) is modern and, today, almost ubiquitous both in states and non-governmental associations. In some of these states one side or the other of this compound format is compromised and exists on paper only -- frequently they take the form of authoritarian regimes in which a ruling group promulgates a formalistic "charter" that is not implemented. My point is that the formal requisites of democratic organization -- public and private -- are widely known and often, though not always, practiced. States (and other organizations) may be considered modern democracies to the degree that they understand and implement this compound institutional structure. Clearly many contemporary states are not modern democracies -- or they may give lip-service to the principles without practicing them.

1c. ALTERNATIVES: PARLIAMENTARY AND PRESIDENTIALIST

With some notable exceptions, all modern democratic organizations can be characterized as presidentialist or parliamentary, based on a fundamental rule that links the head of government to the constitutive system. The presidentialist form evolved first in the United States. It replaces monarchs with presidents elected for a fixed term. They have the authority (at least nominally) to manage the governmental bureaucracy. Some comments on the historical situation that led the "Founding Fathers" of the U.S. "Constitution" to reproduce the powers of the king of England while rejecting the principles that legitimated the monarchy will be discussed below. Concurrently, an elected assembly was created to co-exist with the president on the basis of a principle referred to as the "separation of powers." This principle has been reproduced in all presidentialist regimes -- I use 'presidentialist' in preference to 'presidential' because many parliamentary regimes also have presidents and it is easy to confuse them (Riggs 1994a). However, by "presidentialist" I do not imply an "imperial presidency," which has also become a meaning of "presidentialist." To avoid confusion, I often insert "separation-of-powers" to characterize the type of system I have in mind. By contrast, in parliamentary regimes, a balancing rule prevails that produces the fusion of executive/legislative authority in some kind of cabinet. The cabinet and its leader, a prime minister, needs the support of a parliamentary majority to stay in power with two fundamental consequences. Because the constitutive system in such regimes is fused -- i.e. the chief executive

is accountable to the elected assembly and can be discharged by a vote of no-confidence -deadlock between the two branches can be avoided. Moreover, control over the bureaucracy is enhanced by the fusion of powers -- officials are not held responsible to a multiplicity of centers of authority. This means that they can administer more effectively and also that they can be controlled more effectively. Without claiming that parliamentarism is more or less democratic than presidentialism or that it is a "better" system in any sense, it seems to be apparent that parliamentarism is more likely to survive than presidentialism as a democratic form of governance. On the basis of a statistical analysis of 135 countries observed annually between 1950 and 1990, Prezorski and his associates concluded that "Parliamentary regimes last longer, much longer, than presidential ones..." (Przeworski et al, 1996, p.47)2 This finding reinforces my own earlier conclusions (Riggs 1993). The long-term survival of presidentialism in the U.S. can be explained, I think, by many practices that differ from those found in other presidential regimes (see Riggs 1988, 1994a). I shall not try to describe them here, but they provide a basis for suggesting some of the constitutional practices that could be adopted by presidential regimes wishing to enhance their own prospects for survival and, accordingly, to deal more effectively with the major problems of modernity discussed below.

1d. REGIME CHANGES

Fundamental reforms are vigorously opposed, however, because the beneficiaries of established structures and practices in any system of governance typically rally to defend them against such changes. A possible way to cut this "Gordian Knot" might be to switch from presidentialism to parliamentarism. Unfortunately, this is also a very difficult transition to make. In fact, it is difficult to think of any successful cases -- when Brazil recently put the issue to a plebiscite vote, parliamentarism lost out. In the Philippines, the struggle to abandon presidentialism in favor of parliamentarism has been renewed and is currently going on with, I should imagine, almost no chance of success. An earlier and more serious effort to replace presidentialism with parliamentarism led, in 1973, to the seizure of power by then-president Ferdinand Marcos. A nominally successful case involved the transition from parliamentarism in the first Nigerian republic to presidentialism in the second. Since both "experiments" ended with the seizure of power by a military cabal, it can hardly be considered an exception, however. Perhaps the earliest historical case is that of France where the Second Republic was launched by the election of Louis Napoleon, a man who promptly confronted that country's legislature, creating an impasse that ended only when the president seized power and established the second Empire. The Third republic, which was parliamentary and lasted much longer, was created by a dying monarchy, not as a transition from presidentialism.

My conclusion is that all modern democracies are trapped by the basic form (whether presidentialist or parliamentary) that they first adopted (with a few possible exceptions). Two different sets of historical forces determine this choice: first the rise of modernity in the West, and second its subsequent globalization through the contemporary processes of modernization. No sharp lines can be drawn, chronologically, between these stages, but the first accompanied the emergence of modern states, especially during the nineteenth century, and the second occurred in the successor states that arose following the collapse of all the modern empires in the 20th century. To summarize, the states that were created by revolutionary secession from pre-modern empires, as did the United States and most of Latin America, chose presidentialism as a way to replace kings who, in those days, served concurrently as heads of state and heads of government. By contrast (to simplify the process), regimes that evolved out of a long-term struggle between royal authority and growing bourgeois power were able to compel kings to surrender the right to rule while keeping the right to reign -- and from this evolutionary process parliamentarism emerged throughout Europe. During the contemporary process of modernization, by contrast, successor states tended to adopt the constitutional design of their imperial masters -- except for those that came to power after a prolonged revolutionary struggle where, under Communist Party influence, single-party regimes were established. Where independence was negotiated, however, the agents of imperial power were normally able to "advise" their successors to follow their example. When, as often happened, these embryonic democracies collapsed and military/bureaucratic rule prevailed, one might suppose that more experienced local leaders would have been able to persuade their autocratic elites to surrender power to a more locally appropriate type of democratic government. Usually, however (Nigeria is a striking exception) the military rulers who eventually surrendered power did so in a way that restored the constitutional status quo ante. My point is that, after the basic constitutional choice had been made, regardless of the evident advantages of parliamentarism over presidentialism for the survival of democratic governance, countries that had started out presidentialist have almost never made a successful transition to parliamentarism. Bearing this point in mind, I shall not offer any recommendations to support a shift from presidentialism to parliamentarism. Rather, I think, we need to consider how any constitutional democracy, taking its established form as a given, can select among the institutional options which can be changed those that will most likely enable democracy to survive in their specific situations. In order to make any such changes or reforms, however, we need to understand the basic problems confronting all modern states as contrasted with those that faced pre-modern regimes. Each of these problems confronts modern governments with a new set of challenges that parliamentary regimes, I suspect, are able to meet more easily than presidentialist governments can. To test this claim, we need to have clear notions about what the basic features of modernity are and the challenges they present to any contemporary government.

PART TWO: MODERNITY: THE "IND" TRIAD

Modernity, I believe, can best be understood as an historical process that evolved in the West during the past three or so centuries on the basis of three closely interlocked forces: industrialism, democracy and nationalism, what I like to think of collectively as the IND triad. We usually think of them as separate processes because each has its own history and can trace its origins and evolution to independent forces. This tendency is reinforced by the way we compartmentalize academic disciplines making it easier for economists to focus on industrialism, sociologists on nationalism and political scientists on democracy. However, I believe each depended on and reinforced the others to such a degree that we need to adopt a cross-disciplinary perspective to understand modernity as a single complex or syndrome (Riggs 1994c).3 The relation between industrialism, nationalism and democracy (IND) as major components of modernity may be compared to a braid whose strands have an independent existence yet, when interwoven, create a single entity that is stronger and more visible than any of its constituent hairs. All three strands interact as forces that affect the different forms of governance -- including presidentialism and parliamentarism -- but we need to think about each, separately, in historical perspective. I shall, therefore, discuss each in turn in Part Two of this essay. We should also distinguish historically between the formative stages of modernity -- the forces that brought each facet into existence -- and their contemporary consequences as world movers that have produced what is increasingly called a global village (Khator and Garcia-Zamor). The historical dynamics of invention and evolution differed in many ways from contemporary processes of dissemination and reproduction -- the former produced modernity and the latter modernization. Modernity produced modern states in which all three IND processes intertwine. By contrast, modernization has led to quasi-states and dictatorships in which the three strands of modernity have often become dissociated from each other. Although we like to view modernization as a benign effort made by the former empires to assist their former dependencies, in fact modernization was launched and had already transformed the life of dependent peoples in the imperial possessions long before they were "liberated." Speaking temporally, modernity did not suddenly spring into existence and its forms have continuously changed. We need, therefore, to recognize stages, but I shall refer only to late-modernity as a reference to its contemporary forms and issues: I much prefer this to post-modern, a term that suggests the end of modernity and an indeterminate succeeding state of affairs. It is important to recognize that premodern ideas and institutions persist everywhere while modernity grew and superimposed new forms and practices. Premodern phenomena are more conspicuous in the sucessor states of modern empires than they are in the homelands of these empires -- I shall refer to the latter as the metropoles for lack of a more convenient term. When

we walk, talk, dance, worship, make love, have children and bury our dead, we engage in practices that have survived from ancient times and continue to shape our lives, in the metropoles as everywhere else -- modernity is a kind of frosting over a cake which obscures but does not fundamentally change what remains underneath. Sad to say, this kind of frosting often sweetens the cake, but sometimes it can also pollute it: we need to recognize the diverse consequences of modernity which have always been both desirable and undesirable, positive and negative. We have celebrated the achievements and benefits of modernity so loudly that must of us have not listened to the complaints of those who bitterly experienced its costs. Surely, however, all the proudest accomplishments of modernity have also had tragic consequences -- the two aspects cannot be divorced from each other. Recent airplane disasters symbolize this linkage: without the technological and scientific achievements of the industrial revolution we could not, today, fly so quickly from place to place around the world. Yet, every time we board a plane, we must also face the possibility that everyone on board may die suddenly because of an engine failure or a terrorist's bomb. When we consider the positive and negative aspects of modernity, it may help us to distinguish between its desirable ortho-modern aspects and its negative para-modern consequences. Much of the contemporary debate about modernity seems to assume that we can avoid or transcend it -- I think this is wishful thinking. Modernity is here to stay and we must learn to live with it and do the best we can to understand and cope with its harmful consequences: retrospectively, we focus on the positive aspects of ortho-modernity, but today we have become much more aware of its para-modern aspects. That does not mean that modernity was only a myth, or that it has come to an end. Instead, I think, we need to confront the para-modern beast and do what we can to "slay this dragon." Among other things, we must construct governmental institutions capable of helping us understand and cope with para- modernity using ortho-modern knowledge and technology to help us. Finally, we often use modernism to talk about the mental images or philosophical notions that both contributed to and resulted from modernity and modernization. This includes our conceptual framework of basic values or norms: secularism, individualism, communitarianism, etc. The subject is relevant and fascinating but I cannot deal with it here.4 Instead, let me now turn to each of these major facets of modernity, the IND triad, and consider the challenges they offer to constitutional democracy and, comparatively, to the capacity of presidentialist and parliamentary regimes to deal with them.

Parliamentary versus Presidential governments

Two of the most popular types of democracy are the presidential and parliamentary government systems. Sponsored Links A nations type of government refers to how that states executive, legislative, and judicial organs are organized. All nations need some sort of government to avoid anarchy. Democratic governments are those that permit the nations citizens to manage their government either directly or through elected representatives. This is opposed to authoritarian governments that limit or prohibit the direct participation of its citizens. Two of the most popular types of democratic governments are the presidential and parliamentary systems. The office of President characterizes the presidential system. The President is both the chief executive and the head of state. The President is unique in that he or she is elected independently of the legislature. The powers invested in the President are usually balanced against those vested in the legislature. In the American presidential system, the legislature must debate and pass various bills. The President has the power to veto the bill, preventing its adoption. However, the legislature may override the Presidents veto if they can muster enough votes. The American Presidents broadest powers rest in foreign affairs . The President has the right to deploy the military in most situations, but does not have the right to officially declare war. More recently the American President requested the right to approve treaties without the consent of the legislature. The American Congress denied this bill and was able to override the Presidents veto. In parliamentary governments the head of state and the chief executive are two separate offices. Many times the head of state functions in a primarily ceremonial role, while the chief executive is the head of the nations legislature. The most striking difference between presidential and parliamentary systems is in the election of the chief executive. In parliament systems, the chief executive is not chosen by the people but by the legislature. Typically the majority party in the parliament chooses the chief executive, known as the Prime Minister. However, in some parliaments there are so many parties represented that none hold a majority. Parliament members must decide among themselves whom to elect as Prime Minister . The fusion of the legislative and executive branches in the parliamentary system tends to lead to more discipline among political party members. Party members in parliaments almost always vote strictly along party lines. Presidential systems, on the contrary, are less disciplined and legislators are free to vote their conscious with fewer repercussions from their party. Debate styles also differ between the two systems. Presidential system legislators make use of a

filibuster, or the right to prolong speeches to delay legislative action. Parliamentary systems will call for cloture, or an end to debate so voting can begin. Most European nations follow the parliamentary system of government. Britain is the most well known parliamentary system. Because Great Britain was once a pure monarchy, the function of the head of state was given to the royal family, while the role of chief executive was established with Parliament. Some parliaments, however, do not have a history of monarchy. Israel is a parliamentary system with a president. The president, however, does not hold the same power as a president in a presidential system, but functions as the head of state. In both presidential and parliamentary systems, the chief executive can be removed from office by the legislature. Parliamentary systems use a vote of no confidence where a majority of parliament members vote to remove the Prime Minister from office. A new election is then called. In presidential systems, a similar process is used where legislators vote to impeach the President from office. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, democracy has begun to flourish around the world. As emerging nations struggle to identify themselves, they are also debating which form of democracy is best for them. Depending on the nation and its citizens, they may choose the more classic parliamentary system or the less rigid presidential system. They could also blend to two popular systems together to create the hybrid government that works best for them.

Parliamentary versus genuine democracy

While fighting for one or another democratic right, socialists reject attempts to identify democratic rights with the parliamentary institutions of the capitalist state. Even the most advanced capitalist parliamentary systems offer no long-term guarantee of basic democratic rights. Indeed, the capitalist parliamentary system is inherently undemocratic because it excludes the majority, the working people, from the actual exercise of political power. The party fights for the replacement of the capitalist parliamentary state with a more democratic political system a democratically centralised system of popular power. In a truly democratic state, the supreme power should be vested in a single popular assembly made up of representatives of councils of working people's delegates from each city, town and rural district, functioning as both legislative and executive bodies. Elections to local self-government bodies and to the national assembly should be based on proportional representation. All officials civil, military and judicial should be subject to election. All elected representatives and officials, without exception, should be subject to recall at any time upon the demand of a majority of their electors and should be paid at a rate not exceeding the average wage of a skilled worker. The standing army and police, with their pro-capitalist officer corps, should be replaced by a popular militia indissolubly linked to the factories, mines, offices, farms and progressive mass movements, with commanders drawn from the ranks of the working people. It is only through these measures that a genuinely democratic state, that is, one in which the majority actually rules, can be brought into being and maintained.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Legal Doctrines and PrinciplesDocument3 pagesLegal Doctrines and PrinciplesXymon Bassig67% (3)

- Eo 247Document31 pagesEo 247Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- CLT Realty Corporation vs. Hi-Grade Feeds Corporation, GR No. 160684, 2 September 2015 DigestDocument3 pagesCLT Realty Corporation vs. Hi-Grade Feeds Corporation, GR No. 160684, 2 September 2015 DigestAbilene Joy Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Professional English The Marketing MixDocument13 pagesProfessional English The Marketing MixEnglish Plus Podcast100% (1)

- Application For Relaxation of Terms of BailDocument3 pagesApplication For Relaxation of Terms of BailAisha0% (1)

- Prior Criminal Indictments Against Corey GaynorDocument26 pagesPrior Criminal Indictments Against Corey GaynorPenn Buff NetworkNo ratings yet

- Ra 7942Document26 pagesRa 7942Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Ra 7586Document10 pagesRa 7586Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- RA 1425 (SB 438 and HB 5561)Document2 pagesRA 1425 (SB 438 and HB 5561)Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- PD 442Document273 pagesPD 442Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- RA 6713 - Code of Conduct and Ethical Standard For Public Officials and EmployeesDocument12 pagesRA 6713 - Code of Conduct and Ethical Standard For Public Officials and EmployeesCrislene Cruz83% (12)

- PD 1586Document4 pagesPD 1586Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Ra 343Document1 pageRa 343Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Ombudsman Act of 1989 establishes functional structureDocument12 pagesOmbudsman Act of 1989 establishes functional structurechavit321No ratings yet

- Ra 386Document318 pagesRa 386Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Ra 1319Document4 pagesRa 1319desereeravagoNo ratings yet

- PD 705Document17 pagesPD 705Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- PD 979Document5 pagesPD 979Xymon Bassig0% (1)

- PHILIPPINE CORAL RESOURCES DECREEDocument4 pagesPHILIPPINE CORAL RESOURCES DECREEjenicadizonNo ratings yet

- PD 1487Document6 pagesPD 1487Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- EXECUTIVE ORDER No. 209 July 6, 1987 The Family Code of The PhilippinesDocument43 pagesEXECUTIVE ORDER No. 209 July 6, 1987 The Family Code of The PhilippinesXymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Family Code CodalDocument44 pagesFamily Code CodalLita Indz Nuevo BudomoNo ratings yet

- Jure UxorisDocument2 pagesJure UxorisXymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Eo 141Document2 pagesEo 141Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Eo 124Document4 pagesEo 124Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- The Constitution of JapanDocument15 pagesThe Constitution of JapanXymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Article XI 1987 Philippine ConstitutionDocument3 pagesArticle XI 1987 Philippine ConstitutionreseljanNo ratings yet

- Administrative Order 269Document5 pagesAdministrative Order 269Xymon BassigNo ratings yet

- List of Legal Latin TermsDocument4 pagesList of Legal Latin TermsXymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Mistake of LawDocument3 pagesMistake of LawXymon BassigNo ratings yet

- EO-292 Administrative Code of 1987Document215 pagesEO-292 Administrative Code of 1987Vea Marie RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Imperial Household LawDocument9 pagesImperial Household LawXymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Public International LawDocument11 pagesPublic International LawXymon BassigNo ratings yet

- Beneficiality SpeechDocument6 pagesBeneficiality SpeechLourleth Caraballa LluzNo ratings yet

- RTC has jurisdiction over land disputeDocument3 pagesRTC has jurisdiction over land disputemiloNo ratings yet

- Countering Offshore Tax Evasion: Some Questions and Answers On The ProjectDocument7 pagesCountering Offshore Tax Evasion: Some Questions and Answers On The ProjectMark ReinhardtNo ratings yet

- The Advantages and Disadvantages of Written and Unwritten ConstitutionsDocument3 pagesThe Advantages and Disadvantages of Written and Unwritten ConstitutionsChe Nur Hasikin0% (1)

- International Security and DevelopmentDocument18 pagesInternational Security and DevelopmentAdán De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Politics 12345Document2 pagesPolitics 12345Anitia PebrianiNo ratings yet

- SARO numbers document funding detailsDocument609 pagesSARO numbers document funding detailsBimby Ali LimpaoNo ratings yet

- Massapequa High School Teacher Charged With Transportation and Possession of Child Pornography - USAO-EDNY - Department of JusticeDocument3 pagesMassapequa High School Teacher Charged With Transportation and Possession of Child Pornography - USAO-EDNY - Department of JusticerenagoncNo ratings yet

- A Critical Study of Bail Trends in IndiaDocument13 pagesA Critical Study of Bail Trends in IndiaRAVI VAGHELANo ratings yet

- Witness Protection An Important Measure For The Effective Functioning of Criminal Justice AdministrationDocument14 pagesWitness Protection An Important Measure For The Effective Functioning of Criminal Justice AdministrationPrashant RahangdaleNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument10 pagesReview of Related Literature and StudiesPia Loraine BacongNo ratings yet

- Lyons V US DigestDocument2 pagesLyons V US DigestEmrys PendragonNo ratings yet

- Kedar Nath Singh Vs State of Bihar 20011962 SCs620074COM715340Document20 pagesKedar Nath Singh Vs State of Bihar 20011962 SCs620074COM715340Bishwa Prakash BeheraNo ratings yet

- Atizado Vs PeopleDocument24 pagesAtizado Vs PeopleelobeniaNo ratings yet

- Arellano Law CurriculumDocument14 pagesArellano Law Curriculumdanna ibanezNo ratings yet

- Tropical Homes Vs NhaDocument2 pagesTropical Homes Vs NhaMyra MyraNo ratings yet

- R. v. Ro 2019 S.C.R. 392 - 2019 - Supreme Court of Canada - HTTPS://WWW - SCC-CSC - CaDocument17 pagesR. v. Ro 2019 S.C.R. 392 - 2019 - Supreme Court of Canada - HTTPS://WWW - SCC-CSC - CaHyun-June Leonard RoNo ratings yet

- 215404-2018-Directing All Government Agencies To20181011-5466-1p0kf94 PDFDocument38 pages215404-2018-Directing All Government Agencies To20181011-5466-1p0kf94 PDFRuby MorenoNo ratings yet

- Application For Anticipatory Bail Under Section-438 of The Criminal Procedure Code, 1973Document2 pagesApplication For Anticipatory Bail Under Section-438 of The Criminal Procedure Code, 1973CHIRANJEEVI PONNAGANTINo ratings yet

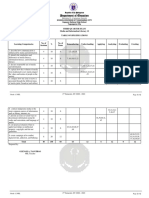

- Department of Education: Third Quarter Exam Media and Information Literacy 12 Table of SpecificationsDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Third Quarter Exam Media and Information Literacy 12 Table of SpecificationsMelanio Florino0% (1)

- List of Government TypesDocument38 pagesList of Government TypesJunelle VillaranteNo ratings yet

- Section 306 Penalizes Abetment of Suicide. It Reads: "If Any Person Commits Suicide, Whoever AbetsDocument2 pagesSection 306 Penalizes Abetment of Suicide. It Reads: "If Any Person Commits Suicide, Whoever AbetsShivi CholaNo ratings yet

- CriminalDocument9 pagesCriminalAlice Marie AlburoNo ratings yet

- TENCHAVES V ESCANO Gr. No. L-19671Document4 pagesTENCHAVES V ESCANO Gr. No. L-19671Nichole LusticaNo ratings yet

- Tenenbaum - First Cir. Appeal - Brief of USDocument68 pagesTenenbaum - First Cir. Appeal - Brief of USChristopher S. HarrisonNo ratings yet