Professional Documents

Culture Documents

FIDIC Disputes

Uploaded by

errajeshkumarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

FIDIC Disputes

Uploaded by

errajeshkumarCopyright:

Available Formats

FIDIC: when is a dispute not a dispute?

Posted by PLC Construction on 2nd April 2012.

Michael Stewart, partner, Pinsent Masons LLP: My last blog looked at the difficulties that can arise in a typical FIDIC scenario where an employer does not honour a dispute adjudication board (DAB) decision that is binding, but not final. This blog looks at the difficulties that can arise in relation to the definition of the dispute that is submitted to the DAB and then to arbitration. To recap, if the contractor does not like the engineers determination of a claim, it refers what is by that stage the dispute to the DAB. The DAB then makes a decision on the matter. If the employer is dissatisfied with the DABs decision, it can give notice of its dissatisfaction. The parties then try and settle the dispute amicably. If that is not possible, the parties can refer the dispute to arbitration. A common scenario This process can give rise to another difficulty. For example, consider this scenario:

The contractor is retained on a civil engineering project under the FIDIC Red Book (1999). At an early stage of the works, the contractor discovers that the site investigation information included within the tender is deficient. The contractor brings this to the attention of the engineer and the matter is discussed in the normal manner. After some delay, the contractor is instructed to carry out additional site investigation. Once the results of those investigations have been considered, the contractor then has to excavate to revised levels, positions and dimensions. The contractor incurs costs in waiting to receive instructions from the engineer, carrying out the additional site investigation and then excavating to the revised levels. The contractor submits a claim under clause 20.1, the engineer determines the claim under clause 3.5 and the contractor then submits the dispute to the DAB, seeking to recover its costs by way of a variation under clause 13.1. The DAB decides the matter, the contractor issues a notice of dissatisfaction and the dispute goes to arbitration.

At this stage, the lawyers become involved. Among other things, they point out that the contractor also has entitlements under clauses 1.19 (delayed drawings or instructions) and 4.12 (unforeseeable physical conditions). The contractor then puts its claim on these alternative bases, as well as advancing its claim for a variation. The employer alleges that the arbitral tribunal has no jurisdiction to deal with the alternative claims brought under clauses 1.19 and 4.12, as they were not put before the DAB, so are not part of the dispute which is permitted to be submitted to arbitration.

What happens here? The underlying facts are identical for all the alternative claims. Does the employers argument have any merit? Is it fair to expect the contractor to have to think of all possible legal and contractual arguments when the dispute is referred to the DAB? If so, would this not defeat the commercial purpose of the tiered dispute resolution provisions, effectively meaning that the contractor would have to retain lawyers or specialist claims advisors during the whole of the works? Surely it must be open to the contractor to refine its entitlements as the dispute progresses through the tiers within clause 20? There is also clause 20.6, which states that neither party shall be limited in the proceedings before the arbitrator(s) to the evidence or arguments previously put before the DAB to obtain its decision, but what does this mean in practice? Witney Town Council v Beam Much will of course depend upon the jurisdiction and the governing law. In terms of the position in England and Wales, some guidance is provided in Witney Town Council v Beam Construction. Although a decision in relation to adjudication, the principles are equally applicable to the scenario set out above. In Witney, Akenhead J held that there was only one dispute between the parties by the time of the service of the notice of adjudication and only one dispute had been referred to adjudication. He therefore rejected the challenge made to the validity of the adjudicators decision. This decision very much depended upon the facts of the case, but Akenhead J helpfully reviewed the relevant authorities and restated the principles that should be applied when considering whether a party has attempted to refer more than one dispute to adjudication. Parallel claims and practicalities The answer to any such jurisdictional challenges is relatively straightforward simply ensure that all parallel or alternative claims are included in the reference to the DAB. However, in the real commercial world, this is far more easily said than done.

HOW NOT TO INTERPRET THE FIDIC DISPUTES CLAUSE: THE SINGAPORE COURT OF APPEAL JUDGMENT IN PERSERO CHRISTOPHER R SEPPL * Partner, White & Case LLP, Paris Special Adviser, FIDIC Contracts

Committee I. INTRODUCTION As a result of the recent decision of the Court of Appeal of Singapore (the CA or the Court) in CRW Joint Operation v. Perusahaan Gas Negara (Persero) TBK 1 (the Persero case), which dismissed an appeal against the judgment of the High Court of Singapore setting aside an International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) arbitration award, there has been increased uncertainty about the effect of a binding, but not final, decision of a DAB under the FIDIC Conditions of Contract for Construction, 1999 (the 1999 Red Book). 2 The ICC Arbitral Tribunal in that case, on the one hand, and two Singapore courts, on the other hand, arrived at widely different interpretations of sub-clauses 20.4 to 20.7 of the 1999 Red Book. In light of this uncertainty, and given that I have been involved in the review and drafting of the disputes clause in the 1999 Red Book since the Fourth Edition was published in 1987, I would like to comment on these decisions, specifically the CA judgment, as it is the lastand finalword from Singapore. 3 Accordingly, in this article I will briefly review the facts of the Persero case (Section II), the ICC arbitration and award (Section III) and the judgments of the High Court (HC) and the CA in Singapore (Section IV). I will then comment on the CA decision (Section V), before drawing some conclusions (Section VI). * The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the law firm or organisation, such as FIDIC, with which he is affiliated. The author is grateful to Matthew Secomb and Diana Bowman, his colleagues at White & Case LLP, Paris, for their comments on this paper in draft. However, only the author is responsible for its contents. 1 [2011] SGCA 33. 2 See, e.g., Frederic Gillion, Enforcement of DAB Decisions under the 1999 FIDIC Conditions of Contract: A Recent Development: CRW Joint Operation v. PT Perusahaan Gas Negara (Persero) TBK [2011] ICLR 388 (hereinafter cited as Gillion) who refers (at p. 389) to the confusing message sent by the High Court judgment. 3 The Court of Appeal is Singapores highest court. Pt 1] How Not to Interpret the FIDIC Disputes Clause 5

You might also like

- A Contractor's Guide to the FIDIC Conditions of ContractFrom EverandA Contractor's Guide to the FIDIC Conditions of ContractNo ratings yet

- FIDIC Guidance On Enforcing DAB DecisionsDocument3 pagesFIDIC Guidance On Enforcing DAB DecisionshaneefNo ratings yet

- Cornes and Lupton's Design Liability in the Construction IndustryFrom EverandCornes and Lupton's Design Liability in the Construction IndustryNo ratings yet

- Clause 14 PDFDocument34 pagesClause 14 PDFR. Haroon Ahmed100% (1)

- Issue RED BOOK (1999) YELLOW BOOK (1999) SILVER BOOK (1999) : Regulation and WorksDocument34 pagesIssue RED BOOK (1999) YELLOW BOOK (1999) SILVER BOOK (1999) : Regulation and WorksPrabath ChammikaNo ratings yet

- Flowchart 9 - Construction ProcessDocument1 pageFlowchart 9 - Construction ProcessiwaNo ratings yet

- Commentary:: Amending Clause 13.1 of FIDIC - Protracted NegotiationsDocument2 pagesCommentary:: Amending Clause 13.1 of FIDIC - Protracted NegotiationsArshad MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Construction Law in the United Arab Emirates and the GulfFrom EverandConstruction Law in the United Arab Emirates and the GulfRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Comments On FIDIC 2017Document2 pagesComments On FIDIC 2017Magdy El-GhobashyNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Role & Authority of The Engineer in FIDIC Red Book 1987Document22 pagesPresentation On Role & Authority of The Engineer in FIDIC Red Book 1987hannykhawajaNo ratings yet

- FIDIC in BahrainDocument12 pagesFIDIC in BahrainUgras SEVGEN50% (2)

- FIDIC and Qatar Law 31 May 2016Document18 pagesFIDIC and Qatar Law 31 May 2016Manoj LankaNo ratings yet

- Fidic Exp PDFDocument34 pagesFidic Exp PDFGaminiNo ratings yet

- How To Legally End A Construction ContractDocument111 pagesHow To Legally End A Construction ContractexistenceunlimitedNo ratings yet

- Claims Chart Under FIDICDocument4 pagesClaims Chart Under FIDICMohamad Hessen100% (1)

- ContractFIDIC Comparison AutosavedDocument3 pagesContractFIDIC Comparison Autosavedhamood afrikyNo ratings yet

- Fidic InfoDocument39 pagesFidic InfoAMTRIS50% (2)

- FidicDocument30 pagesFidicTejay Tolibas100% (1)

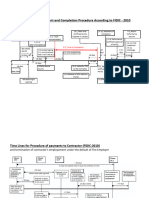

- Flow Charts of FIDIC-2010Document7 pagesFlow Charts of FIDIC-2010Irshad Ali Durrani100% (1)

- FIDIC Comparison PeterAtkinsonDocument11 pagesFIDIC Comparison PeterAtkinsonFirasAlnaimiNo ratings yet

- 0.FIDIC Red Book-Top SheetDocument8 pages0.FIDIC Red Book-Top SheetDINESHNo ratings yet

- Flow Chart Under Fidic 1999Document30 pagesFlow Chart Under Fidic 1999rawbean100% (2)

- Module ReviewDocument16 pagesModule ReviewHaneef MohamedNo ratings yet

- Construction Contract VariationsDocument24 pagesConstruction Contract Variationserrajeshkumar100% (2)

- Contractor Design: Plant and /or High Unforeseen RisksDocument2 pagesContractor Design: Plant and /or High Unforeseen Risksdineshkmr373No ratings yet

- Delays and Disruptions Under FIDIC 1992Document3 pagesDelays and Disruptions Under FIDIC 1992arabi1No ratings yet

- Construction Dynamics Solutions - OverviewDocument4 pagesConstruction Dynamics Solutions - OverviewkkkkkNo ratings yet

- Head Office Overhead RevisitedDocument5 pagesHead Office Overhead RevisitedManoj LankaNo ratings yet

- Herbett - Time BarDocument3 pagesHerbett - Time BarPameswaraNo ratings yet

- QSMMDocument158 pagesQSMMizac007No ratings yet

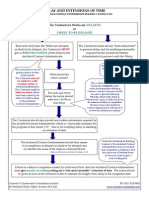

- Uk Case Briefs On Extension of Time ClaimsDocument8 pagesUk Case Briefs On Extension of Time ClaimsJimmy KiharaNo ratings yet

- Construction Contracts v1.0Document25 pagesConstruction Contracts v1.0Abhishek RathoreNo ratings yet

- Jan08 Q&A 307097079Document4 pagesJan08 Q&A 307097079pdkprabhath_66619207No ratings yet

- FCCMDocument2 pagesFCCMMohanna Govind100% (1)

- Coronavirus COVID19 - Client GuidanceDocument15 pagesCoronavirus COVID19 - Client GuidanceManoj Ek50% (2)

- Avoiding Pitfalls in Construction - A Review of FIDIC Forms of ContractDocument5 pagesAvoiding Pitfalls in Construction - A Review of FIDIC Forms of ContractSohail MalikNo ratings yet

- September 2013 Q&ADocument11 pagesSeptember 2013 Q&Apdkprabhath_66619207No ratings yet

- Extension of Time Under JCT (Illustration)Document1 pageExtension of Time Under JCT (Illustration)LGNo ratings yet

- FIDIC Short Form Cover & ContentsDocument10 pagesFIDIC Short Form Cover & ContentsNavneet SinghNo ratings yet

- Advanced Construction Law - Q2Document4 pagesAdvanced Construction Law - Q2Neville OkumuNo ratings yet

- Practical Approach To The Fidic PrinciplesDocument14 pagesPractical Approach To The Fidic Principlesmou777No ratings yet

- Red Book - ProceudresDocument3 pagesRed Book - Proceudresmohammed100% (1)

- The Five Golden Principles (FIDIC's Protection of Genuinity)Document6 pagesThe Five Golden Principles (FIDIC's Protection of Genuinity)Anonymous pGodzH4xLNo ratings yet

- Fidic 87-99Document1 pageFidic 87-99Tharaka KodippilyNo ratings yet

- Letter Writing RulesDocument4 pagesLetter Writing RulesBogdanNo ratings yet

- Jan 11-Q&A-1Document13 pagesJan 11-Q&A-1pdkprabhath_66619207No ratings yet

- RED Book Vs Civil Code by AnandaDocument35 pagesRED Book Vs Civil Code by AnandalinkdanuNo ratings yet

- FIDIC - New 1999 Edition of The Red Book Impartiality of The EngineerDocument5 pagesFIDIC - New 1999 Edition of The Red Book Impartiality of The EngineerSajjad Amin AminNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To The 1999 Red & Yellow Books, Clause8-Commencement, Delays & SuspensionDocument4 pagesA Practical Guide To The 1999 Red & Yellow Books, Clause8-Commencement, Delays & Suspensiontab77zNo ratings yet

- Prolongation & Disruption ClaimsDocument13 pagesProlongation & Disruption ClaimsGiora Rozmarin75% (4)

- City Inn V Shepherd Construction Presentation May 2011Document19 pagesCity Inn V Shepherd Construction Presentation May 2011jscurrie6614100% (1)

- The Importance of Interpretation On Red Flag Clauses To Fulfil Parties' Obligations EffectivelyDocument30 pagesThe Importance of Interpretation On Red Flag Clauses To Fulfil Parties' Obligations EffectivelyGokul100% (1)

- 01 The Law and Practice of Delay Claims A Practical Introduction TrainorDocument19 pages01 The Law and Practice of Delay Claims A Practical Introduction TrainorMOHNo ratings yet

- With You There Are Only 4 in The List So Far and Let Us Hope The List Will Grow SoonDocument4 pagesWith You There Are Only 4 in The List So Far and Let Us Hope The List Will Grow Soonpdkprabhath_66619207No ratings yet

- Assignment - Claims Management Mr. Tilak KolonneDocument2 pagesAssignment - Claims Management Mr. Tilak KolonneDammika PereraNo ratings yet

- 1 - Mr. Toby Randle - FIDIC Red and Pink Books DevelopmentDocument15 pages1 - Mr. Toby Randle - FIDIC Red and Pink Books DevelopmentMin Chan MoonNo ratings yet

- C Se Morning Sadhana Prayer Book 2015Document12 pagesC Se Morning Sadhana Prayer Book 2015errajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- The Path of Kriya Yoga: An IntroductionDocument7 pagesThe Path of Kriya Yoga: An IntroductionGowthamanBalaNo ratings yet

- Kriya Yoga Swami YoganandaDocument14 pagesKriya Yoga Swami Yoganandaadi_vijNo ratings yet

- 78890-YSS NCR Enewsletter - August 2016Document7 pages78890-YSS NCR Enewsletter - August 2016errajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Aarati To Babaji Mahavatar: Table of ContentDocument2 pagesAarati To Babaji Mahavatar: Table of ContenterrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- QEV Summer 2019 v4Document2 pagesQEV Summer 2019 v4errajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Schedule 2020Document2 pagesSchedule 2020errajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Urban Yogi EnglishDocument27 pagesUrban Yogi EnglishrockeybroNo ratings yet

- IAEA General Conditions of ContractDocument9 pagesIAEA General Conditions of ContracterrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- The Great Maha Avatar BabajiDocument4 pagesThe Great Maha Avatar BabajierrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- General Kriya FlyerDocument1 pageGeneral Kriya FlyererrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Babaji Yantra Pooja For NetDocument4 pagesBabaji Yantra Pooja For NeterrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Bhakti Marga Art Work CatalogueDocument25 pagesBhakti Marga Art Work CatalogueerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- SDM OnlyLove BabajiDocument8 pagesSDM OnlyLove Babajiலோகேஷ் கிருஷ்ணமூர்த்திNo ratings yet

- Kriya Babaji NagarajDocument2 pagesKriya Babaji Nagarajkarbh89100% (1)

- Death Before Life After Life, Gregg Taylor PDFDocument11 pagesDeath Before Life After Life, Gregg Taylor PDFerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Mahavatar BabajiDocument13 pagesMahavatar BabajiPochareddy RameshNo ratings yet

- Trainning 100 Worst Government Mistakes in Government ContractingDocument5 pagesTrainning 100 Worst Government Mistakes in Government ContractingerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Architects Legal HandbookDocument11 pagesArchitects Legal HandbookerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Construction Contract VariationsDocument24 pagesConstruction Contract Variationserrajeshkumar100% (2)

- Only The Content of The FIDIC Subcontract 2009Document8 pagesOnly The Content of The FIDIC Subcontract 2009errajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Case Law On The Fidic Forms of ContractDocument17 pagesCase Law On The Fidic Forms of ContracterrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Qatar Civil Code Important ArticlesDocument1 pageQatar Civil Code Important ArticleserrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- X7 Legal Tips On UAE Construction LawDocument1 pageX7 Legal Tips On UAE Construction LawerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Construction Law Handbook Vivian Ramsey Important PagesDocument983 pagesConstruction Law Handbook Vivian Ramsey Important Pageserrajeshkumar100% (4)

- Fidic & Qatar Civil CodeDocument1 pageFidic & Qatar Civil CodeerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Construction Contract VariationsDocument24 pagesConstruction Contract Variationserrajeshkumar100% (2)

- Fidic & Qatar Civil CodeDocument1 pageFidic & Qatar Civil CodeerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- Fidic & Qatar Civil CodeDocument1 pageFidic & Qatar Civil CodeerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- d31pz Unit 09 - Managing Payment - Fidic Red Book - 2 Slides Per PageDocument9 pagesd31pz Unit 09 - Managing Payment - Fidic Red Book - 2 Slides Per PageerrajeshkumarNo ratings yet

- 50-Cuenco v. Cuenco G.R. No. 149844 October 13, 2004Document7 pages50-Cuenco v. Cuenco G.R. No. 149844 October 13, 2004Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Tanada Vs HRET (G.R. No. 217012)Document14 pagesTanada Vs HRET (G.R. No. 217012)j531823No ratings yet

- John Walter Sneed, Jr. VS State of Nevada, Et Al., - Document No. 25Document3 pagesJohn Walter Sneed, Jr. VS State of Nevada, Et Al., - Document No. 25Justia.com100% (2)

- Corporate & Business Law: Essential Elements of The Legal SystemDocument40 pagesCorporate & Business Law: Essential Elements of The Legal SystemAdegbola AyodejiNo ratings yet

- Admin Digests (Nov. 28)Document5 pagesAdmin Digests (Nov. 28)BrunxAlabastroNo ratings yet

- Tarun Tyagi Vs Central Bureau of InvestigationDocument6 pagesTarun Tyagi Vs Central Bureau of Investigationmadhav hedaNo ratings yet

- National Power Corporation vs. Tiangco, 514 SCRA 674, February 06, 2007Document14 pagesNational Power Corporation vs. Tiangco, 514 SCRA 674, February 06, 2007Carmel Grace KiwasNo ratings yet

- Johnson V Johnson (2000) HCA 48 201 CLR 488 174 ALR 655 74 ALJR 1380 (7 September 2000)Document22 pagesJohnson V Johnson (2000) HCA 48 201 CLR 488 174 ALR 655 74 ALJR 1380 (7 September 2000)James JohnsonNo ratings yet

- People v. JalbuenaDocument19 pagesPeople v. JalbuenaTreb LemNo ratings yet

- 2007 F. Schwartz, C.konrad Institutional ArbitrationDocument44 pages2007 F. Schwartz, C.konrad Institutional Arbitrationcarol malinescuNo ratings yet

- University of Phoenix False Claims Act LawsuitDocument18 pagesUniversity of Phoenix False Claims Act LawsuitBeverly Tran0% (1)

- People Vs PiccioDocument4 pagesPeople Vs PiccioRuffa ReynesNo ratings yet

- SWS Vs AsuncionDocument1 pageSWS Vs Asunciongianfranco06130% (1)

- Apple Law SuitDocument9 pagesApple Law SuitAzman UsmaniNo ratings yet

- Premiere Development Bank V FloresDocument3 pagesPremiere Development Bank V FloresLUNANo ratings yet

- People vs. Chaw Yaw ShunDocument2 pagesPeople vs. Chaw Yaw ShunTiffany AnnNo ratings yet

- Maloto v. CA DigestDocument2 pagesMaloto v. CA Digestclaire beltranNo ratings yet

- Prosecution MotionDocument16 pagesProsecution MotionsaukvalleynewsNo ratings yet

- 208 Luna vs. IAC - TENEPEREDocument1 page208 Luna vs. IAC - TENEPEREVince Llamazares LupangoNo ratings yet

- Property CasesDocument31 pagesProperty CasesKaren GinaNo ratings yet

- Gomaa v. Drug Enforcement Administration - Document No. 6Document2 pagesGomaa v. Drug Enforcement Administration - Document No. 6Justia.comNo ratings yet

- WP 39218 2012Document3 pagesWP 39218 2012Vigneshwar Raju PrathikantamNo ratings yet

- 108 Paculdo V Regalado 345 SCRA 134 2000Document4 pages108 Paculdo V Regalado 345 SCRA 134 2000.No ratings yet

- North City Area-Wide Council, Inc. v. George W. Romney, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Department of Housing and Urban Development, 469 F.2d 1326, 3rd Cir. (1972)Document10 pagesNorth City Area-Wide Council, Inc. v. George W. Romney, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Department of Housing and Urban Development, 469 F.2d 1326, 3rd Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chase Vs CFI of Manila (The Taliño)Document2 pagesChase Vs CFI of Manila (The Taliño)AlexandraSoledadNo ratings yet

- United States v. Peter Canessa, 644 F.2d 61, 1st Cir. (1981)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Peter Canessa, 644 F.2d 61, 1st Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Nazareno vs. CADocument2 pagesNazareno vs. CACheryl P. GañoNo ratings yet

- SMCEU vs. BersamiraDocument2 pagesSMCEU vs. BersamiraPatrizia Ann FelicianoNo ratings yet

- People V Tubongbanua Sec 14 Rule 110Document3 pagesPeople V Tubongbanua Sec 14 Rule 110kdchengNo ratings yet

- Eric Murdock United Airlines Federal Lawsuit DocumentsDocument24 pagesEric Murdock United Airlines Federal Lawsuit DocumentsBenjamin ZhangNo ratings yet

- Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our PlanetFrom EverandCrossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our PlanetRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful DesignFrom EverandTo Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful DesignRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (138)

- The Things We Make: The Unknown History of Invention from Cathedrals to Soda CansFrom EverandThe Things We Make: The Unknown History of Invention from Cathedrals to Soda CansNo ratings yet

- Composite Structures of Steel and Concrete: Beams, Slabs, Columns and Frames for BuildingsFrom EverandComposite Structures of Steel and Concrete: Beams, Slabs, Columns and Frames for BuildingsNo ratings yet

- The Things We Make: The Unknown History of Invention from Cathedrals to Soda CansFrom EverandThe Things We Make: The Unknown History of Invention from Cathedrals to Soda CansRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Geotechnical Engineering Calculations and Rules of ThumbFrom EverandGeotechnical Engineering Calculations and Rules of ThumbRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Troubleshooting and Repair of Diesel EnginesFrom EverandTroubleshooting and Repair of Diesel EnginesRating: 1.5 out of 5 stars1.5/5 (2)

- Structural Cross Sections: Analysis and DesignFrom EverandStructural Cross Sections: Analysis and DesignRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)

- Rocks and Minerals of The World: Geology for Kids - Minerology and SedimentologyFrom EverandRocks and Minerals of The World: Geology for Kids - Minerology and SedimentologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn BridgeFrom EverandThe Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn BridgeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (59)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Summary of Neil Postman's Amusing Ourselves to DeathFrom EverandSummary of Neil Postman's Amusing Ourselves to DeathRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- The Finite Element Method: Linear Static and Dynamic Finite Element AnalysisFrom EverandThe Finite Element Method: Linear Static and Dynamic Finite Element AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- CAREC Road Safety Engineering Manual 3: Roadside Hazard ManagementFrom EverandCAREC Road Safety Engineering Manual 3: Roadside Hazard ManagementNo ratings yet

- Finite Element Analysis and Design of Steel and Steel–Concrete Composite BridgesFrom EverandFinite Element Analysis and Design of Steel and Steel–Concrete Composite BridgesNo ratings yet

- Cable Supported Bridges: Concept and DesignFrom EverandCable Supported Bridges: Concept and DesignRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Construction Innovation and Process ImprovementFrom EverandConstruction Innovation and Process ImprovementAkintola AkintoyeNo ratings yet

- Rock Fracture and Blasting: Theory and ApplicationsFrom EverandRock Fracture and Blasting: Theory and ApplicationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)