Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History of Film-Other (Ed) Cinema Histories Essay

Uploaded by

Skye McCulloughOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History of Film-Other (Ed) Cinema Histories Essay

Uploaded by

Skye McCulloughCopyright:

Available Formats

McCullough 1 Skye McCullough THFM 2620: History of Film Melinda Lewis April 28, 2011 Other(ed) Cinema Histories

Assignment Jon is a mild mannered film critic who just found out he is HIV positive. Luke is a short tempered drifter who also has the disease. When the two men meet, they form a relationship that is only strengthened through this common bond. In George Araki's 1992 film, The Living End, the audience is introduced to these two men and watches as they meet and react to one another and the disease that they know is inside them. This film was one of the first films in the first wave of the New Queer Cinema movement. This film centers on Jon and Luke, who both become criminals fairly early on in the film, as they wander aimlessly across the nation. Homosexuals as well as heterosexuals were portrayed and critiqued in this film and audiences across the nation found themselves split in what to think of it. They could not decide if it was raw and moving or silly and depressing. Many were disapproving of the New Queer Cinema movement and this film because of the character types and the content of the story, but The Living End gave audiences a different perspective of AIDS and the havoc that the disease can wreak. New Queer Cinema arose in the early 1990s. At this time, more people, for the most part, were showing up at cinemas throughout the nation than in the few decades before. Hollywood found out that more money spent on advertising a film meant more money to be made in profit upon the film's release, thus the late 80s and early 90s were a time of high budget and high grossing films. The 90s was a time of mega-spending and visual effects for the film industry in

McCullough 2 America. There was a higher demand for big time stars to be put into films, the internet was starting to pick up steam, and home video cameras were being distributed. Digital production was gaining ground. Cook states that: ...near the end of this period (the 1980s), as the internet became a growth industry and the era of digital production dawned, the American majors began to realize that someday soon their movies would be distributed online or downloaded into digital displays by satellites. (Cook, 877) With this realization came the birth of the DVD. There was also a rise in independent films and amateur films being made at the time. Home movies had recently become very popular among suburban homes and many homes owned video cameras. Many independent films were being made and sent to film festivals across the nation. It was in this festival scene that New Queer Cinema first came to be seen. New Queer Cinema originated in the United States in the very early 1990s. In the first years of the decade, film festivals such as Sundance were shocked and surprised by the success of films that would later be known as New Queer Cinema (NQC). Before this movement in the 90s, films that portrayed homosexual content were always very light hearted. They never showed graphic scenes or images and they always ended with a song and a smile. During the New Queer Cinema Movement however, this need for happy endings and subdued content became a thing of the past. There was now a surge in films aimed at homosexuals made by homosexual filmmakers and commenting on issues that concern said community. Because of the new approach to this type of cinema, the trend of these films was moving from the confines of positive imagery to something vastly different. In the article Hollywood is Burning the critic Karl Soehnelin was quoted as

McCullough 3 saying that there was an emerging flock of filmmakers is using provocative subject mattertransgression, gender bending, and rude activism to create challenging visions of sexual identity, (220). This change could be seen in the films of Greg Araki, Todd Haynes, Marlon Riggs, and others. Not only did the films and filmmakers of this time break apart the expected content of such films, but they also redefined many other filmic qualities. Griffin and Banshof stated that New Queer Cinema actively breaks down filmic categories such as genre, fiction realism, and documentaryas well as deconstructs essentialist concepts of history, race, nation, gender, and sexuality, (222). These films in the New Queer Cinema movement all had a sense of camp to them, though not camp in the way that many would now define the term. To define the term camp as it would be used in describing the films of the New Queer Cinema movement, it is necessary to look a little into the history of the struggle for gay rights. In the 1970s petitions in the gay districts around the nation, especially those in California, flourished with the movements and actions of influential leaders such as Harvey Milk and others. At this point, the homosexual community was mainly concerned with obtaining equal rights and representation in the politics of the United States. In the 1980s however, the focus of many gay rights groups and individuals shifted. Though the community still focused on their lack of political and social equality, when the AIDS virus surfaced and began to spread the homosexual community turned their attention towards the disease. The thriving hedonistic lifestyles that were common in southern California were now gone as the impact of the disease sunk in. Since the 1980s gay rights groups have been supporting a policy of non-assimilation as well as constantly trying to raise awareness and funds to combat HIV and AIDS.

McCullough 4 In the 1980s, this new need for non-assimilation of the homosexuals into heterosexual society created camp. In the article Camp and Queer and the New Queer Director, Glyn Davis states in response to one Honey Glass that 'Queer camp,' then, it would seem, is used by queers to speak to other queers, and though it may ocassionally be humorous, is never 'merely' funny; such are subtle intricacies of queer camp that it cannot be used by anyone from the 'outside,' the 'them' being referred to in the definition obviously meaning heterosexuals, (57). This camp is often marked with both serious and ironic homages to other famous works and people and a nostalgia not only for the time in the 60s and 70s when the sexual revolution was in full swing in California as well as other parts of the nation but more commonly, for a time when being gay/lesbian was criminal.This form of camp is used very often by Araki in his film, The Living End. In The Living End, one of the two main characters, Luke, is anything but the kind, mild mannered boy that audiences have thus far expected to see in this type of film. In fact, Luke is a criminal. He is a man who believes that he has nothing to loose and because of this feels that he can let his whims and desires carry him to wherever he chooses. He even goes as far as killing cops and thugs on the street. This characterization of one of the main characters reflects that nostalgia for the time when being gay was deemed criminal. The audience can also see the nostalgia that the filmmaker has for the times of the sexual revolution in the 60s and 70s, though he does not particularly look on this revolution with pride. One can see this negative nostalgia when Jon and Luke are sitting at the table discussing HIV and Luke states, We're victims of the sexual revolution. The generation before us had all of the fun, and we get to pick up the tab. This scene illustrates the strained feeling that homosexuals of the generation were feeling at the time. It was much like what young men were feeling when they were drafted for the war. They did not cause

McCullough 5 the problem, why should they have to live with the consequences? 'Queer camp' is also marked by the need to reference and pay homage to other famous works and people whether it be ironically or seriously. For example, Jon is a film critic at times and in his apartment the audience sees many posters that pay homage to French New Wave director, Jean Luc Goddard, just as the two main character's names together form the latter's. The subject matter of New Queer Cinema is more often than not focused on HIV and AIDS. In Hollywood is Burning, Griffin and Benshof state that New Queer Cinema has been defined as, a form and expression that emerges from the cataclysm of AIDS in the Western World (221). Later in the article, Monic Pearl is quoted as agreeing with this assessment of NQC but elaborates on Griffin and Benshof's claim saying: New Queer Cinema provides another way of making sense out of the virus, [one] that does not placate and does not provide easy answers- that reflects rather than corrects the experience of fragmentation, disruption, unboundaried identity, incoherent narrative, and inconclusive endings. It is a way of providing meaning that does not change or sanitize the experience. (Monica B. Pearl, 221) This is exactly the content of The Living End. Luke is flippant toward society and the confines of the law. He does whatever he wants because he knows that he is going to die someday sooner than he would have without the virus. On the same level, Jon would not have run off with a criminal had he not found out that he had HIV. The audience sees that Jon is mild and reserved, but once he is diagnosed and introduced to Luke, he too picks up the motto Fuck the world. Along with the major theme of AIDS and HIV in the film, the characters often contemplate what happens after death. On multiple occasions Luke asks Jon What do you think happens after

McCullough 6 we croak? These metaphysical and spiritual conversations permeate the film as do the boy's discussions of death and what it feels like to die. Luke, who is the more compulsive and self indulgent of the two, has heard and believes that dying feels like a very intense orgasm and so when he does have to go, he wants to go with the man that he believes he loves, Jon. Jon on the other hand does not seem to buy into such ideas and is the more pessimistic of the two when it comes to thoughts about what happened to you after you die. Luke believes in an afterlife and some sort of continuation after life, whereas Jon feels that belief in the afterlife is just romantic garbage and that no such place can exist which explains why Luke lives life to the fullest without fear of consequences and death while Jon lives in more or less of a shell. In their relationship, Luke is defiantly the freer of the two men, believing that having AIDS is a reason to do whatever you want to do. In her article on New Queer Cinema, Michele Aaron comments on this nonchalant view of death saying ...the films (of the NQC movement) in many ways defy death...the key way in which death is defied is in the terms of AIDS. Death is defied as the life-sentence passed by the disease, (5). In many ways these films are saying that life with the disease is not the most pleasant, but it is often the choice that people make when faced with it or death. This approach to the AIDS problem is one that had not been seen much before, but was now beginning to surface throughout film. The relationships in The Living End, whether heterosexual or homosexual, are strained to say the least. At the very beginning of the film the audience is introduced to an eccentric lesbian couple that picks Luke up off the road. These women are presented as ridiculous criminals. In fact, Fern is said to have killed quite a few men. At the start of the film, Jon has just gotten out of a relationship to find that he is HIV positive. Luke, on the other hand, was not previously in a

McCullough 7 relationship, but soon found a one night stand who later is killed by his wife in front of Luke for his infidelity. When the two main characters finally do meet, they do so in the strangest of circumstances; Luke is running because he had recently murdered three men and Jon happens to be passing in his car and stops to pick him up. Jon then takes Luke home and their relationship begins that night. Their meeting and subsequent relationship is odd to say the least and as the film proceeds, Jon and Luke's relationship is the focus of the film, but the audience is also shown a few heterosexual relationships. Darcy's worry for Jon causes her relationship with Peter to suffer and eventually end. The audience is also exposed to the heterosexual couple that are leaning on Jon's car fighting. They are obviously not that happiest of couples and this is seen in their argument, but they get upset and ban together when their spat is interrupted by Jon. Once Jon gets into the car, the two get right back to their altercation. This portrayal of a heterosexual relationship is not one that had been seen often in films before. More often than not the heterosexual couple was happy and content with two cars and a house in the suburbs, but that is not the case here, nor is it the case with all of the other relationships in the film. The Living End challenged the perceptions Americans had about relationships in the 1990s. George Araki and the New Queer Cinema films of the 1990s challenged the way that homosexuals were represented in the media. They took all of the common conceptions that American viewers had about the lifestyle and threw them out the window in favor of new and radical portrayals. The new charters that were introduced were not the shy, sweet, boy and girl next door types anymore, they were real (to an extent) and focused on real issues, though not always in the most realistic ways. Though not all homosexuals were fond of the representations, this style of filmmaking will forever leave its mark on Queer Cinema and American Cinema in general.

McCullough 8

McCullough 9 Works Cited Aaron, Michele. "New Queer Cinema: An Introduction." New Queer Cinema: a Critical Reader. Ed. Michele Aaron. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2004. 3-15. Print. Benshoff, Harry M., and Sean Griffin. "Hollywood Is Burning: New Queer Cinema." Queer Images: a History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Pub., 2006. 219-46. Print. Cook, David A. A History of Narrative Film. 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004. Print. Davis, Glyn. "Camp and Queer and the New Queer Director: Case Study--Gregg Araki." New Queer Cinema: a Critical Reader. Ed. Michele Aaron. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2004. 53-67. Print. The Living End. Dir. Gregg Araki. Cineplex Odeon Films, 1992. DVD.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Lister - 2002 - Sexual CitizenshipDocument4 pagesLister - 2002 - Sexual CitizenshipPablo Pérez NavarroNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Not Trans Enough: The Intersections of Whiteness & Nonbinary Gender IdentityDocument54 pagesNot Trans Enough: The Intersections of Whiteness & Nonbinary Gender IdentityItsBird TvNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- LGBTDocument3 pagesLGBTapi-279290977No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Manalastas Torre Fil LGBT ActivismDocument41 pagesManalastas Torre Fil LGBT Activismvlabrague6426No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Erinyes Submission To Australian Human Rights CommissionDocument52 pagesErinyes Submission To Australian Human Rights CommissionZoe Ellen BrainNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- DeLeon v. Perry Declaration of Ilan H Meyer 11-22-2013Document64 pagesDeLeon v. Perry Declaration of Ilan H Meyer 11-22-2013Daniel Williams100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Gay and Lesbian LanguageDocument44 pagesGay and Lesbian LanguageHenrique AmorimNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Strong Thesis Statement On Gay MarriageDocument8 pagesStrong Thesis Statement On Gay Marriagedonnabutlersavannah100% (2)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Dictionary of LGBT TermsDocument2 pagesDictionary of LGBT Terms00041xyzNo ratings yet

- The Top Ten Harms of Same-Sex "Marriage": Immediate EffectsDocument13 pagesThe Top Ten Harms of Same-Sex "Marriage": Immediate EffectsyohoyonNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- 2nd Quarter Handout IntroDocument10 pages2nd Quarter Handout IntroXianPaulette Mingi ManalaysayNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

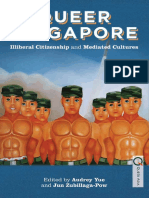

- (Queer Asia) Audrey Yue, Jun Zubillaga-Pow-Queer Singapore - Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures-Hong Kong University Press (2013)Document267 pages(Queer Asia) Audrey Yue, Jun Zubillaga-Pow-Queer Singapore - Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures-Hong Kong University Press (2013)Jo JoNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- An Archive of Feelings Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public CulturesDocument404 pagesAn Archive of Feelings Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public CulturesBob PatinioNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- After Love by Noelle M. StoutDocument49 pagesAfter Love by Noelle M. StoutDuke University Press50% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Super Super Like Final N TLG Final Research Manuscript - Group 4 MagentaDocument84 pagesSuper Super Like Final N TLG Final Research Manuscript - Group 4 MagentaAngel LambanNo ratings yet

- Lorena Russell - Dog-Women and She-Devils - The Queering Field Monstrous WomenDocument17 pagesLorena Russell - Dog-Women and She-Devils - The Queering Field Monstrous Womendanutza123No ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sexual Woman in Latin American LiteratureDocument363 pagesThe Sexual Woman in Latin American LiteratureViviana Hernández100% (1)

- Women Together. Women Apart. Tirza True Latimer - Portraits of Lesbian ParisDocument236 pagesWomen Together. Women Apart. Tirza True Latimer - Portraits of Lesbian ParisShirley McClureNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Homoerotics of Travel: People, Ideas, Genres: RuthvanitaDocument17 pagesThe Homoerotics of Travel: People, Ideas, Genres: RuthvanitaAlejandroMiraveteNo ratings yet

- Constructing the Lesbian Subject in Charlotte Brontё's Villette and Daphne Du Maurier's RebeccaDocument65 pagesConstructing the Lesbian Subject in Charlotte Brontё's Villette and Daphne Du Maurier's Rebecca13u5tedNo ratings yet

- D&D - Book of Erotic Fantasy Remastered v11Document206 pagesD&D - Book of Erotic Fantasy Remastered v11Anonymous AlIISgV80% (5)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Gender(s), Power, and Marginalization: Typical QuestionsDocument5 pagesGender(s), Power, and Marginalization: Typical Questionscyril100% (1)

- Judith Gardiner - Female MasculinityDocument28 pagesJudith Gardiner - Female MasculinityDimitria HerreraNo ratings yet

- Safe Space by Christina HanhardtDocument60 pagesSafe Space by Christina HanhardtDuke University Press100% (1)

- Boricua LesbiansDocument22 pagesBoricua LesbiansChimps Aponte100% (1)

- Wilets - LGBT Rights and International Law Post-ColonialDocument55 pagesWilets - LGBT Rights and International Law Post-ColonialstumarvelNo ratings yet

- Adams, Jo Et Al - Explore, Dream, Discover - Working With Holistic Models of Sexual Health and Sexuality, Self Esteem and Mental HealthDocument124 pagesAdams, Jo Et Al - Explore, Dream, Discover - Working With Holistic Models of Sexual Health and Sexuality, Self Esteem and Mental HealthPaul CNo ratings yet

- Seeking Ecstasy On The BattlefieldDocument20 pagesSeeking Ecstasy On The BattlefieldAngélica Pena-MartínezNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- IRQO: Humanity Denied: The Violations of The Rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Persons in IranDocument29 pagesIRQO: Humanity Denied: The Violations of The Rights of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Persons in IranLGBT Asylum NewsNo ratings yet

- 1978 - Susan Leigh Star - The Politics of Wholeness II - Lesbian Feminism As An Altered State of ConsciousnessDocument21 pages1978 - Susan Leigh Star - The Politics of Wholeness II - Lesbian Feminism As An Altered State of ConsciousnessEmailton Fonseca DiasNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)