Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1 s2.0 S0901502705807118 Main

Uploaded by

ast810Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1 s2.0 S0901502705807118 Main

Uploaded by

ast810Copyright:

Available Formats

Trauma; preprosthetic surgery Invited review

Reconstructive preprosthetic surgery

I. Anatomical considerations

J. I. Cawood, R. A. Howell." Reconstructive preprosthetic surgery. I. Anatomical considerations. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1991; 20." 75-82. Abstract. When considering preprosthetic surgery of the edentulous jaws, it is important that the clinician fully understands the anatomical consequences of reduction of the residual ridges. Based on a classification of the edentulous jaws, changes in the relationship of the jaws to each other, in muscle relations and function, in the oral mucosa and in facial morphology have been measured relative to the stage of resorption of the edentulous jaws.

J. I. C a w o o d 1, R. A . H o w e l l 2 1Maxillofaeial Unit, Royal Infirmary, Chester, and aLiverpool Dental Hospital, UK

Key words: preprosthetic surgery; edentulous jaws; classification; anatomy; alveolar resorption. Accepted for publication 1 December 1990

Reduction of the residual ridge is a chronic progressive process whose rate varies not only between different individuals but within the same individual at different times 1. In a detailed longitudinal study, TALLGREN observed that 8 although the greater proportion of bone loss occurred within the first year of tooth loss, the process continued at a slower rate over the 25 years for which the subjects were followed (Fig. 1). She also noted that, in general, the amount of bone loss in the mandible is four times greater than in the maxilla. Using clearly defined, reproducible reference points of the edentulous jaws, CAWOOD & HOWELL4 analysed patterns of alveolar resorption from a sample of 300 dried skulls. Based on this objective study, a pathophysiological classification of alveolar resorption was established which describes 6 stages of resorption (Fig. 2A, B, C, D) and (Fig. 14, A, B, C, D, E, F).

ANTERIOR

MANDIBLE

MM 35

R5155 ~

I.AEMAL

5 MM

15 MM

II

MANDIBLE

III

iv

Vl

ROBTERIOR

'i{;ii!~..

B

I 115

IV V Vl

I!

II MAXILLA

Ul

ANTERIOR

MM 0 10

HEIGHT MM

30 A MANOIBLE

, i i 1o 13

POSTERIOR

I|

MAXILLA

nl

IV

Vl

25

MM

lO

i lO O

1 3

4o

25

Fig. 1. Mean reduction in anterior height of the alveolar ridges over 25 years (after

TALLGRENS).

v Vl IV Fig. 2. A: classification of anterior mandible (anterior to mental foramina); B: classification of posterior mandible (posterior to mental foramina); C: classification of anterior maxilla; D: classification of posterior maxilla.

II

Ill

76

Cawood and Howell

Class I - dentate. Class II - post extraction. Class I I I - rounded ridge, adequate height and width. Class IV - knife edge ridge, adequate height, inadequate width. Class V - flat ridge, inadequate height and width. Class VI - depressed ridge with varying degrees of basal bone loss, that may be extensive but follows no predictable pattern. The main conclusions arising from the study were: [i] Basal bone does not change shape significantly unless subjected to harmful local effects such as the overloading of ill-fitting dentures. [ii] Alveolar bone changes shape significantly. [iii] In general, changes of shape of the alveolar bone follow a predictable pattern. [iv] Pattern of bone loss varies with site. Anterior mandible (anterior to mental foramina) bone loss is mainly horizontal from the labial aspect. Posterior mandible (posterior to mental foramina) bone loss is mainly vertical. Anterior maxilla bone loss is mainly horizontal from the labial aspect. Posterior maxilla bone loss is mainly horizontal from the buccal aspect. [v] Stage of bone loss can vary anteriorly and posteriorly and between jaws (Fig. 15, A, B).

UFH 43~

UFH 4B~

LPH 57~

LFH 52~

ORTHOGNATHIC

FACE

EDENTULOUS

FACE

Consequence of tooth loss

Loss of teeth and reduction of the residual ridge lead to changes in the relationship of the jaws to each other, in muscle relations and function, in the oral mucosa and in facial morphology. The classification of the edentulous jaws 4 forms a basis for a systematic assessment relating the stage of resorption to changes in the shape and relationship of the jaws and soft tissue integument.

Fig. 3. Changes between Class I and Class VI jaw relations. A: anteroposterior and vertical interarch changes and associated prognathism of the mandible; B: transverse and vertical interarch changes. Note the reverse relationship of the edentulous and dentate jaws due to resorption patterns causing the maxillary arch to become progressively narrower and the mandibular arch to become progressively broader; C: lateral cephalometric tracings of orthognathic face (Class I) and edentulous face (Class V), illustrating changes in anterior facial proportions of the edentulous face due to the autorotation of the mandible causing a decrease in lower face height and increase of chin prominence. UFH: upper face height: LFH: lower face height.

Interarch changes

With progressive resorption from Class I to Class VI, there are 3 dimensional changes in jaw relations. Anteroposteriorly, the mandibular and maxillary arches become shorter (Fig. 3A). Transversely, due to the pattern of resorption,

the maxillary arch becomes progressively narrower, whilst the mandibular arch becomes progressively broader. (Fig. 3B). Vertically, the interarch distance increases, although this is counteracted to some extent by the vertical shortening of the lower face caused by the closing movement or autorotation of the mandible producing a more prominent chin and prognathic jaw (Fig. 3C, D).

Reconstructive preprosthetic surgery

Muscle changes

77

The attachments of the circumoral and floor of mouth musculature delineate the extent of the vestibular and lingual sulci. With continued loss of alveolar bone from Class I to Class VI, these muscles become progressively superficial (Fig. 4A, B, C, D, E, F).

BUCCAL

'

Fig. 4. Attachment of the circumoral and floor of mouth musculature, showing how they become increasingly superficial as bone loss progresses. A: dentate mandible (Class I), buccal aspect; B: edentulous mandible (Class V), buccal aspect: (1) mentalis, (2) depressor labii inferioris, (3) depressor anguli oris, (4) buccinator; C: dentate mandible, lingual aspect; D: edentulous mandible, lingual aspect: (5) genioglossus (superior) and geniohyoid (inferior), (6) digastric (anterior belly), (7) mylohyoid. E: dentate maxilla (Class I), buccal aspect; F: edentulous maxilla (Class V), buccal aspect: (1) dilator naris, (2) compressor naris, (3) depressor septi, (4) buccinator, (5) levator anguli oris.

78

Cawood and Howell

ANTERIOR

MM

MANDIBLE CHANGES

12

POSTERIOR

MM

MANDIBLE CHANGES

MUCOSA

Mucosal changes

MUCOSAL 12

= ~

MUCOSAL

UNATTACHEO

UNATTACHED

MUCOSA

ATTACH~ D

MUCOSA

,~ " r A C H

MUCOS

Ill

IV

Vl

III

IV

VI

Fig. 5. Differences between mean values of attached and unattached mucosa. A: anterior mandible; B: posterior mandible.

II

III

IV

VI

Fig. 6. Progressivereduction of residual ridges from Class I to Class VI showing vertical ridge resorption of the posterior mandible, decreasing attached mucosa (heavy line) and changing muscle relations.

There is quantitative and qualitative reduction of the soft tissue support as well. WATT & MACGREGOR compared the 9 area ofperiodontium supporting a tooth with the small area of mucoperiosteum remaining after tooth loss. They calculated that the mean surface area is reduced from 45 to 23 cm squared in the edentulous maxilla and to 12 cm squared in the edentulous mandible. In the edentulous jaw, the mucosa covering the residual ridge is partly attached and partly unattached. The attached mucosa corresponds to the attached gingiva originally surrounding the natural teeth. Unlike the periodontal ligament, the mucosa is not a specialized supporting tissue, and excessive pressure causes pain and a pathological response 1. As the attached mucosa is bound to bone it is more able than the unattached mucosa to withstand loading pressure. CAWOOD & HOWELL measured the 5 amount of attached and unattached mucosa relative to t h e stage of jaw resorption. As can be seen in (Fig. 5A, B) the amount of attached and unattached mucosa diminishes significantly from Class I to Class VI. The progressive muscle and mucosal changes that accompany jaw atrophy are illustrated in Fig. 6. It should be noted that as a result of alveolar bone loss, the inferior alveolar canal becomes relatively superficial. Changes in mandibular blood supply are seen. Initially, the blood supply is primarily centrifugal. With loss of teeth and the periodontium, the blood supply of the edentulous mandible becomes centripetal (Fig 7).

e/

CENTRIFUGAL

CENTRIPETAL

Fig. 7. Mandibular blood supply: centrifugal in the dentate jaw, centripetal in the edentulous

jaw.

Reconstructive preprosthetic surgery

/" /f

Facial changes

79

Fig. 8. The '<facialcurtain" and the "dental bulge". Loss of anterior teeth causes collapse of circumoral muscles and shortening of the buccinator distorting the face (after WATT & MAcGREoOR9).

Fig. 9. Muscles of facial expression which decussate to form the modiolus lateral to the commissure.

These intraoral changes are also reflected in the facial morphology. WAXY & MACGREGOR liken the circu9 moral and facial musculature to a curtain draped between the maxilla and mandible (Fig. 8). Loss of anterior teeth removes the "dental bulge" and causes shortening of the buccinator muscle and consequent distortion of the facial curtain. The muscles of facial expression decussate to form the modiolus (Fig. 9) and intersect the fibres of the orbicularis oris muscle. With tooth loss and reduction of the residual ridge, there is a change in direction and a loss of tone of the muscles of facial expression. The modiolus collapses inwards and backwards (Fig. 10A, B). The orbicularis oris also collapses with inversion of the "J" shape arrangement of the muscle fibres (Fig. l l a , B). CAWOOD examined changes of the edentulous facial form by measuring the nasolabial angle, commissure width, lower face height and chin prominence relative to the stage of jaw atrophy. As can be seen in (Fig. 12A, B, C, D) facial form alters from Class I to Class VI. The nasolabial angle increases and the commissure width decreases significantly. These changes occur soon after tooth loss but continue to change with increasing jaw atrophy. Reduction of the lower face height and concomitant increase in the chin prominence occur late and are associated with advanced jaw atrophy namely Class V and VI (Fig. 13, A, B).

ORBICULARIS ORIS CHANGES

MOD|OLUS DENTATE MOOIOLUS I~DENTULOUS LA // ZM r /

ZM

>B

Fig. 10. Collapse of elevator and depressor muscles and modiolus following loss of "dental bulge" and atrophy of edentulous jaws. A: frontal view showing medial displacement of modiolus and related muscles; B: lateral view showing posterior displacement of modiolus and related muscles. OO: orbicutaris oris; LA: levator anguli oris; ZM: zygomaticus major and minor; B: buccinator; DA: depressor anguti oris.

Fig. 11. Orbicularis oris muscle and relationship of elevator muscles. A: dentate (Class I), elevator muscles intersect "J" shape arrangement of orbicularis oris muscle fibres; B: edentulous (Class VI), showing associated collapse and distortion of orbicularis muscle fibres.

80

Cawood and Howell

NASOLABIAL ANBLE LABIAL COMMISURE WIOTH

140 130 a 120 110 D 100

.

MM R<O'O01 EO 4O

_

p<o.ool

2O

A

LOWER MM

,,,

FACE

,~ - ~

HEIGHT

B

CHIN MM 10 P ~ 0,001 PROMINENCE

70 EO 50 40

, I , III J IV

'

'

P<

0.001

ill

IV

~,

Fig. 12. Differences between mean values of lower face morphology and progressive resorption of the edentulous jaws. A: nasolabial angle; B: commissure width; C: lower face height; D: chin prominence. Note that the increase in nasolabial angle and decrease in commissure width occur as an early manifestation of tooth loss whilst the decrease in lower face height and increase in chin prominence occur as a late change associated with advanced atrophy of the jaws.

Fig. 13. A: dentate face (Class I) - frontal and lateral; B: edentulous face (Class VI) frontal and lateral showing characteristic changes of lower face height, commissure width, nasolabial angle and chin prominence.

Reconstructive preprosthetic surgery

81

Fig. 14. A: Class III mandible; B: Class III maxilla, note rounded ridge form of adequate height and width; C: Class IV mandible; D: Class IV maxilla, note knife edge ridge form of adequate height and inadequate width. The unsupported attached mucosa spills over the knife edge bony ridge; E: Class V mandible, flat ridge form of inadequate height and width, note loss of sulcus, prominence of genial tubercles relative to the residual ridge and thin strip of residual attached mucosa; F: Class V maxilla, flat ridge form of inadequate height and width, note loss of sulcus depth. Residual mucosa is flabby due to loss of supporting bone.

Awareness of the pattern of resorption of the edentulous jaws and associated soft tissue changes enables clinicians to anticipate and possibly avert future problems.

Fig. 15. Variations of ridge forms. A: anterior mandible - Class IV; posterior mandible Class V; B: anterior maxilla - Class V; posterior maxilla - Class III; anterior mandible Class I; posterior mandible - Class V

'The same manner that the blinde man worketh in hewygne of a log, so doth. a cyrurgeon that knoweth not the nathomye.' The Questyonary of Cyrurgeons, Trans. Guy De Chauliac (1363).

References Discussion There is a need for an internationally accepted classification that describes the stages of resorption of the residual ridges simply and accurately to improve communication between clinicians. Previous attempts to classify the edentulousjaws are unsatisfactory since they are too subjective in nature and incomplete 2,3,6,7. The classification proposed overcomes these objections since it has been derived from objective measurements from which 6 stages of resorption can be clearly identified. Determination o f the particular stage of resorption is accomplished simply and quickly by manual and visual inspection alone (Fig. 14A, B, C, D, E, F). Furthermore, the classification is versatile allowing the distinction between different stages of resorption occurring anteriorly and posteriorly and between jaws (Fig. 15A, B). Tooth loss results in irreversible changes in shape and relationship of the jaws and soft tissue integument. Until now it has not been possible to quantify these changes sequentially. Using the classification and the 6 distinct stages of resorption as a basis for comparison, it was possible to measure the changes in the relationship of the jaws to each other, the muscle relations, the mucosal changes and the alteration of facial form relative to the particular stage of reduction o f the residual ridge. 1. ATWOODDA, CoY WA. Clinical cephalometric and densitometric study of reduction of residual ridges. J Prosthet Dent 1971: 26: 210-95. 2. ATWOODDA. Post extraction changes in the adult mandible as illustrated by microradiographs of midsagittal sections and serial cephalometric roentgenograms. J Prosthet Dent 1963: 13: 810-24. 3. BRaNEMARKPI, ZARRG, AL~R~KTSSONT. (eds). Tissue-integrated protheses. Osseointegration in clinical dentistry. Berlin: Quintessence, 1985. 4. CAWOOD JI, HOWELL RA. A classification of the edentulous jaws. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988: 17: 232-6. 5. CAWOOD JI, HOWELL RA. Anatomical considerations in the selection of patients for preprosthetic surgery of the edentulous jaws. In: Williams DF, ed. Current

82

Cawood and Howell

8. TALLGRENA. The continuing resorption of the residual alveolar ridges in complete denture wearers: A mixed longitudinal study covering 25 years. J Prosthet Dent 1972: 27: 120-32. 9. WATT DM, MACGREGORAR. (eds). Designing complete dentures. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1976: 4-14.' 10. WILKm ND. The role of the prosthodontist in preprosthetic surgery. J Prosthet Dent 1975: 33: 386-96. Address: J. L Cawood Maxillofacial Unit Royal Infirmary Chester CH1 2AZ UK

perspectives on implantable devices. Connecticut: JAI Press, 1989: Vol 1: 139-80. 6. KENTJN, Q ~ JH, ZIDEMF, Gu~ed~ IR, BOYr, PJ. Alveolar ridge augmentation rE using non-resorbable hydroxyapatite with" or without autogenous cancellous bone. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1983: 41: 629-42. 7. MERCIER P, LAmNTANT R. Residual alveolar ridge atrophy: Classification and influence of facial morphology. J Prosthet Dent 1979: 41: 90-100.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Application of Erich Arch BarDocument23 pagesApplication of Erich Arch BarDennis Andrew RemigioNo ratings yet

- GenTorque Con VB6 CODE PDFDocument518 pagesGenTorque Con VB6 CODE PDFhfalanizNo ratings yet

- 05.12 Anatomy of The Larynx & Physiology of PhonationDocument30 pages05.12 Anatomy of The Larynx & Physiology of PhonationReg LagartejaNo ratings yet

- (K24) Acute & Chronic LaryngitisDocument47 pages(K24) Acute & Chronic LaryngitisSyarifah Fauziah100% (3)

- Mastoidectomy VS Tympanoplasty - A Conceptual Renaissance. Preamble To An Original Method of Mastoidectom PDFDocument5 pagesMastoidectomy VS Tympanoplasty - A Conceptual Renaissance. Preamble To An Original Method of Mastoidectom PDFPutu Reza Sandhya PratamaNo ratings yet

- Haircuts Just Above Your Shoulders - Google SearchDocument1 pageHaircuts Just Above Your Shoulders - Google SearchBrynnleigh SmithNo ratings yet

- Radioimagistica SNC LP Stud 2020Document108 pagesRadioimagistica SNC LP Stud 2020MosiwiNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes in Anatomy Embryology of The Oral CavityDocument9 pagesLecture Notes in Anatomy Embryology of The Oral Cavitykasonde bowaNo ratings yet

- The Eight Components of A Balanced SmileDocument17 pagesThe Eight Components of A Balanced SmileJose AriasNo ratings yet

- Thyroid ReportDocument31 pagesThyroid ReportMarion PerniaNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of The EyesDocument2 pagesAnatomy of The EyesTricia De TorresNo ratings yet

- CAP Protocol-2016 Larynx - HighlightedDocument7 pagesCAP Protocol-2016 Larynx - Highlightedpath2016No ratings yet

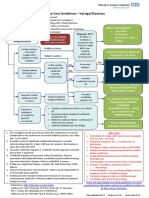

- ENT Vertigo FINAL v0.41Document1 pageENT Vertigo FINAL v0.41Farmasi BhamadaNo ratings yet

- Treatment of An Ankylosed Central Incisor by Single Tooth Dento-Osseous Osteotomy and A Simple Distraction DeviceDocument9 pagesTreatment of An Ankylosed Central Incisor by Single Tooth Dento-Osseous Osteotomy and A Simple Distraction DeviceJuan Carlos MeloNo ratings yet

- Appearance VocabularyDocument2 pagesAppearance VocabularyagaNo ratings yet

- The Diagnosis and Management ofDocument3 pagesThe Diagnosis and Management ofPreetam PatnalaNo ratings yet

- Circle WillisDocument42 pagesCircle WillisShazada KhanNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Frontal SinusDocument77 pagesApproaches To Frontal SinusHossam Elden Helmy HaridyNo ratings yet

- Ent PPT On Pharyngeal AbscessDocument20 pagesEnt PPT On Pharyngeal AbscessDocwocNo ratings yet

- First Periodical Test Science and Health 3Document4 pagesFirst Periodical Test Science and Health 3Bianca Camille Quiazon AguilusNo ratings yet

- Unlocking Orthodontic Malocclusions An Interplay Betw - 1998 - Seminars in OrthDocument10 pagesUnlocking Orthodontic Malocclusions An Interplay Betw - 1998 - Seminars in OrthmikeekimNo ratings yet

- Ent Imp Points To Diagnose ScenariosDocument46 pagesEnt Imp Points To Diagnose Scenariosusmandumassar0% (1)

- AnemiaDocument9 pagesAnemiaManjeevNo ratings yet

- Submental Artery Island Flap Technique For Head Neck ReconstructionDocument18 pagesSubmental Artery Island Flap Technique For Head Neck ReconstructionMahir NuredinNo ratings yet

- Anterior Clinoidectomy Using An Extradural and Intradural 2-Step Hybrid TechniqueDocument10 pagesAnterior Clinoidectomy Using An Extradural and Intradural 2-Step Hybrid TechniquekushalNo ratings yet

- Human hair experiment characteristics under SEMDocument2 pagesHuman hair experiment characteristics under SEMAngielenNo ratings yet

- MnemonicsDocument11 pagesMnemonicsanon-626602No ratings yet

- Soft Tissue Analysis: Dr. Ayushi Toley PG Ist YearDocument70 pagesSoft Tissue Analysis: Dr. Ayushi Toley PG Ist YearAyushi ToleyNo ratings yet

- Maxillofacial Trauma Le Fort 2Document120 pagesMaxillofacial Trauma Le Fort 2Irene UdarbeNo ratings yet

- Foreign Bodies in OtolaryngologyDocument31 pagesForeign Bodies in OtolaryngologyTarek Abdel FattahNo ratings yet