Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pretext

Uploaded by

mansonrossOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pretext

Uploaded by

mansonrossCopyright:

Available Formats

by Jimmie Mesis PI Magazine

Gathering Information... Pretexting from the FTCs Point of View

Many professional investigators have expressed their concerns and confusion about utilizing the investigative practice of pretexting. Whether it is a simple pretext to conrm if a subject is home, or a pretext to acquire case information discretely from neighbors, the practice of pre texting has been an indispensable tool used by investiga tors and law enforcement for decades. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLB) signed into law in 1999 specically addresses pretexting as an illegal act punishable under federal statues. However, the Act specically addresses pretexting only as it pertains to its use in acquiring nancial information from consumers or nancial institutions. One would then assume that any pretexting not deal ing with such nancial information would be permissible. Unfortunately, thats not the case. Merely by its denition, to pretext is to pretend that you are someone who you are not, telling an untruth, or creating deception. When a business entity, such as a private investiga tor, SIU insurance investigators and an adjuster just to name a few conducts any type of deception, it falls under the authority of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). This federal agency has the obligation and author ity to insure that consumers are not subject to any unfair or deceptive business practices. Thats where the Federal Trade Commission Act comes into play. Section 5 of the FTCA states, in part: Whenever the Commis sion shall have reason to believe that any such person, partnership, or cor poration has been or is using any un fair method of competition or unfair or deceptive act or practice in or affect ing commerce, and if it shall appear to the Commission that a proceeding by it in respect thereof would be to the inter est of the public, it shall issue and serve upon such person, partnership, or corpo ration a complaint stating its charges in that respect In an effort to get a denitive deni tion of pretexting and the potential risks and penalties for conducting pretexts, PI Magazine was granted an interview with Joel Winston, Associate Director of the FTC, Division of Financial Practices.

36 NBIZ Fall 2006

His ofce has the responsibility to monitor and regulate the use of pretexting. The following interview clearly outlines several areas of pretexting normally conducted by investigators. I would suggest that you read the answers carefully and refer to them often. PIM: What is the FTCs denition of pretexting as it pertains to the GLB? (Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act) Winston: First, we should dispel the misimpression, if there is one, that the pretexting provisions of GLB only apply if the pretexter is getting nancial information. Actually, what the statue says is if you are getting any personal, non-public information from a nancial institution or the consumer, that is cov ered by the statue. It relates to the consumers relationship with the nancial institution. So, if for example, the pretexter is using false pretenses to get from the consumers bank, the consumers address, that would be covered. Or, if they are going to the consumer and getting the name of their bank through false pretenses, that would be covered. The determining principle is that its only pretexting if the information is obtained through false pretenses. That is, some false statement, misrepresentation, or fraud. The message is if you are trying to get this sort of information; then you can not use improper means, you can not tell lies in order to get this information. PIM: What if I already have a unique identier, such a date of birth or So cial Security number, and I speak to a person, under false pretenses, only to conrm that the person I am speaking to is my subject? Would that be allowed? Winston: I dont think that would be pretexting, because it is not relating to a nancial institution. Conceivably, it could be considered a depictive practice, but we would have to consider it on a case-by-case basis. It doesnt seem like a matter the FTC would be concerned with, but if you were calling the bank to get information, that would be pretexting. PIM: What If I call a bank to determine the approximate balance in an account? I properly identify myself by name and ask if a check will clear, with me providing them the account number and they give it to me. Is this a GLB violation? Winston: As long as you have not said that you are the customer, or said anything that isnt true, or used false pretenses, it would not have violated the GLB Act. If you dont actually have a check and you are trying to discern whether there is money in the account, then you are pretexting. If you are not telling the truth when speaking to the bank, you are pretexting. PIM: Law enforcement and professional investigators have used sim ple pretext as a means of acquiring information. Is it the FTCs posi tion that all pretexts are unlawful even when it is not related to personal nancial information? Winston: The only thing the GLB Act covers is nancial information, infor mation from a nancial institution, or a customers relationship with that nan cial institution. The other statue that might apply is the FTC Act itself, which prohibits deceptive practices. Now thats a very broad concept and covers a wide range of falsehoods and misstatements. I suppose its possible that a PI thats going around to a neighbor posing as someone who he isnt in order to learn the location of the target would be engaged in some form of deception. However, thats really not a matter that the FTC would consider a priority. It is not our priority to be challenging the functions of a PI that are conceivably de ceptive during a one on one transaction with someone, as opposed to looking at some broad practices that might cause harm to numerous individuals. PIM: What steps has the FTC taken to identify pretexters? Winston: We have in the past been quite busy surng the net and looking

www.westernhs.com Tel: (713) 849-2045

LANDSCAPE MANAGEMENT PLANT LEASING IRRIGATION

NBIZ Fall 2006

37

at advertisements. A couple of years ago we had a program (Operation Detect Pretext) where we identied people who appeared to be advertising pretexting service. We sent out warning letters to them and followed up. In some cases, we brought a series of cases to litigation. We remain interested in situations where there is an ongoing pattern of pretexting. We continue to investigate improper cases and do forward cases to the Justice Department for criminal prosecution, if we feel the behavior is sufciently serious. We dont have any one specic way by which we identify pretexters. We rely on tips from the industry, our monitoring efforts, and consumer claimants. Information can come to us from any source, such as an article in a newspaper. PIM: What type of penalties can violators of the GLB expect as it pertains to pretexting for nancial information? Winston: What we have done in some of our pretexting cases is require that the pretexter give back the money, the prots, made from the pretexting. In the cases involving particularly egregious behavior, there are criminal provisions and we would refer them to the Department of Justice for possible criminal prosecution. PIM: How does the FTC address pretexting under the unfair business or deceptive practices clause? Winston: There are legal denitions of what deceptive and unfair practices are, which are available on our website. Traditionally, a deceptive practice is when you misrepresent a fact to the consumer in the course of selling them something. What makes pretexting a little different is that obviously, the pretex ter is not selling anything to the consumer. So, there has been a fair amount of discussion about how exactly does the theory of deception apply to a pretex ting situation. Part of that is because the person who is the recipient of the mis representation is different from the person who is hurt by it. In other words, the pretexter is telling a falsehood to the bank, but the person who actually suffers the harm is the consumer. So, its an issue which we feel falls within the deni tion of deception, but its never really been tested in the courts. There is also a separate theory of unfairness, which is essentially where you are undertaking a practice that causes substantial injury to a consumer. The issue of pretexting would then be, if you are pretexting, what harm does that cause the consumer and that would be determined by the facts in a particular case. PIM: Do you classify the acquisition of telephone toll records as a clear violation of deceptive business practices?

Winston: Its not what we tradi tionally look at as deception because youre deceiving party A, but party B is the actual party being harmed. But, we believe that, even though it has not been tested in the courts, that acquiring toll records through false statements constitutes decep tive business practices. PIM: Is this an area that the FTC is going to start looking into? Winston: We are aware that there have been some concerns about that and were continuing to consider it. PIM: Can clients who hire investi gators or info brokers who violate GLB be prosecuted? Winston: Yes, under the law they can, but there has to be a showing of knowledge. If the person who hired the pretexter had no idea how the in formation was going to be acquired or didnt specically know that pre texting was going to be used, then no, they would not have violated GLB. However, when a PI subcon tracts to another investigator, the PI should insure that the subcontractor is not violating GLB. The PI should not just rely on the subcontractors word, but should know how the in formation will be acquired.

Jimmie Mesis is the editor-in-chief of PI Magazine.com, the trade magazine for private investigators. He is an internationally recognized and award winning private investigator with 28 years of investigative experience. Jimmie trains more than 3,000 private investigators each year at conferences and seminars throughout the USA and the United Kingdom.

38 NBIZ Fall 2006

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Diary of Anne ListerDocument28 pagesDiary of Anne ListerSandra Psi100% (5)

- Haines Man Sentenced To 20 Years in Prison For Sexually Exploiting MinorsDocument2 pagesHaines Man Sentenced To 20 Years in Prison For Sexually Exploiting MinorsAlaska's News SourceNo ratings yet

- Laguna Tayabas Bus Co V The Public Service CommissionDocument1 pageLaguna Tayabas Bus Co V The Public Service CommissionAnonymous byhgZINo ratings yet

- Pastor's Notes:: Woodruff Church of God E-Edition Newsletter September 30, 2014Document6 pagesPastor's Notes:: Woodruff Church of God E-Edition Newsletter September 30, 2014woodruffcog100% (1)

- Various Cases in ConflictsDocument221 pagesVarious Cases in ConflictsHollyhock MmgrzhfmNo ratings yet

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel World Tallest Statue ComingDocument3 pagesSardar Vallabhbhai Patel World Tallest Statue ComingKunal GroverNo ratings yet

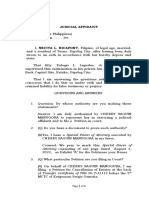

- JUDICIAL AFFIDAVIT RicafortDocument4 pagesJUDICIAL AFFIDAVIT RicafortEulogio LagudasNo ratings yet

- Letter of Appointment (HKDocument4 pagesLetter of Appointment (HKSikkandhar JabbarNo ratings yet

- Zakat On Pension and AnnuityDocument2 pagesZakat On Pension and AnnuityjamalaasrNo ratings yet

- Suikoden V - Guides - Duel Guide - SuikosourceDocument6 pagesSuikoden V - Guides - Duel Guide - SuikosourceSteven PrayogaNo ratings yet

- Hack Instagram MethodesDocument20 pagesHack Instagram MethodesKamerom Cunningham100% (4)

- Civil procedure; Prescription of claims in intestate proceedingsDocument11 pagesCivil procedure; Prescription of claims in intestate proceedingsFrance De LunaNo ratings yet

- RADICAL ROAD MAPS - The Web Connections of The Far Left - HansenDocument288 pagesRADICAL ROAD MAPS - The Web Connections of The Far Left - Hansenz33k100% (1)

- EPQRDocument4 pagesEPQRShrez100% (1)

- PGK Precision Artillery KitDocument2 pagesPGK Precision Artillery KithdslmnNo ratings yet

- Development of ADR - Mediation in IndiaDocument8 pagesDevelopment of ADR - Mediation in Indiashiva karnatiNo ratings yet

- The Ideology of The Islamic State PDFDocument48 pagesThe Ideology of The Islamic State PDFolivianshamirNo ratings yet

- Notice of Intent fee scheduleDocument10 pagesNotice of Intent fee scheduleCarl M100% (5)

- Statement of Claim by Kawartha Nishnawbe Mississaugas of Burleigh FallsDocument63 pagesStatement of Claim by Kawartha Nishnawbe Mississaugas of Burleigh FallsPeterborough ExaminerNo ratings yet

- 51st SMS Pan Atlantic Omnibus PollDocument32 pages51st SMS Pan Atlantic Omnibus PollDirigo BlueNo ratings yet

- The Normative Implications of Article 35 of the FDRE ConstitutionDocument23 pagesThe Normative Implications of Article 35 of the FDRE ConstitutionAbera AbebeNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules discrimination in San Francisco laundry ordinanceDocument6 pagesSupreme Court rules discrimination in San Francisco laundry ordinanceQQQQQQNo ratings yet

- Calape National High School Summative Test 3 English 10Document2 pagesCalape National High School Summative Test 3 English 10Jenifer San LuisNo ratings yet

- Waiving of Right Must Be Consented To by All Due Process RightsDocument17 pagesWaiving of Right Must Be Consented To by All Due Process RightsTitle IV-D Man with a plan100% (2)

- JTNews - September 16, 2011 Section ADocument40 pagesJTNews - September 16, 2011 Section AJoel MagalnickNo ratings yet

- 1st Merit List BS Zoology 1st Semester 2023 Morning19Document2 pages1st Merit List BS Zoology 1st Semester 2023 Morning19Irtza MajeedNo ratings yet

- Philippine special penal laws syllabus covering death penalty, VAWC, juvenile justice, firearms, drugs, anti-graftDocument2 pagesPhilippine special penal laws syllabus covering death penalty, VAWC, juvenile justice, firearms, drugs, anti-graftJoanne MacabagdalNo ratings yet

- Talks With Laden: .RobertDocument5 pagesTalks With Laden: .RobertTheNationMagazineNo ratings yet

- Hassan El-Fadl v. Central Bank of JordanDocument11 pagesHassan El-Fadl v. Central Bank of JordanBenedictTanNo ratings yet

- Aphra BehanDocument4 pagesAphra Behansushila khileryNo ratings yet