Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Afghanistan Electoral System

Uploaded by

Adnan YusufzaiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

The Afghanistan Electoral System

Uploaded by

Adnan YusufzaiCopyright:

The Afghanistan Electoral System, Processes and Outcomes through the Prism of the Performance of the Government and

Opposition Parties: Political parties, electoral systems and democracy: A cross-national analysis

1.1.1 Background

The successful conclusion of the 2004 Presidential election and the 2005 National Assembly and Provincial Council elections represent major achievements for Afghanistan and for the Afghan electoral administration. Some credit for this success also lies with the legislative framework, which has proved workable under very difficult circumstances. However, while the current electoral legal framework has served reasonably well, the experience of those two elections has highlighted a number of shortcomings, as was made clear in the final report of the Joint Electoral Management Body (JEMB). The need for a review of the legal framework was also highlighted by the Post-Election Strategy Group, which was composed of representatives of the JEMB, the Government of Afghanistan, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) and other stakeholders.

With the successful legislative elections behind us and no election planned, 2006 provides a valuable opportunity to review the framework with an eye to correcting the weaknesses in the current system and also to initiate, for the first time in Afghanistans post-Taliban history, a national discussion regarding the future of the electoral system, a discussion that will help strengthen the quality and legitimacy of the electoral system

1.1.2 Components of Legal framework:

1. The Constitution The Constitution includes a number of basic provisions relating to elections, including the requirement that elections be held at defined times to fill the following offices and assemblies: The Presidency The Meshrano Jirga (or House of Elders, the upper house of the National Assembly) The Wolesi Jirga (or House of People, the lower house of the National Assembly) Provincial Councils

District Councils Municipal Councils Mayors Village Councils With the exception of the Meshrano Jirga, 1/3 of which is appointed by the President, with the remainder being selected by the Provincial and District Councils, the constitution does not specify the system to be used in any of the elections. 2. The Electoral Law The Electoral Law governs Presidential, National Assembly, Provincial Council and District Council elections. It was drafted in early 2004 by international advisors to the Joint Electoral Management Body in consultation with the Office of the President. Prior to the 2005 National Assembly and Provincial Council elections, a number of amendments were made to the Electoral Law, chief among which was the creation of an independent Electoral Complaints Commission (ECC) to respond to allegations of fraud and other misconduct. Owing largely to a shortage of time, neither the original version of the Electoral Law nor the amendments were subject to any public debate or input from stakeholders before they were enacted by Presidential Decree. 3. The Municipal Election Law In 2003 the Interim Government of Afghanistan, pursuant to its authority under the Bonn Agreement, issued a Municipal Election Law which provides for the election of municipal councils and mayors under the supervision of an electoral management body drawn from among government ministries. However, shortly thereafter, Afghanistan adopted the Constitution, which among other things, requires that elections be administered by an Independent Electoral Commission. For this reason, although it remains in force, the Municipal Election Law cannot be implemented in its current form. The PESG has considered the issue and produced a concept paper on municipal elections that incorporates a number of elements from the Municipal Election Law. 4. Presidential Decrees and Orders The President has issued a number of stand-alone Decrees and Orders to address specific election-related issues. These are: a) Presidential Decree No. 39 on the Establishment of the Interim Afghan Electoral Commission of 26 July 2003, which establishes the IEC and appointed its first members. Also defines in very general terms the role of the IEC during the 2004 election;

b) Presidential Decree No. 40 on the Establishment of the Joint Electoral Management Body of 26 July 2003, which establishes the JEMB and describes its membership and powers during the 2004 general election; c) Presidential Decree No. 110 on the Basics of Holding Elections During the Transitional Period of 18 February 2004, which describes in detail the role of the Joint Electoral Management Body and its Secretariat in elections held during the Transitional period; d) Presidential Decree No 21 on the Formation of the Independent Electoral Commission of January 19, 2005, which appoints the current members of the IEC; e) Presidential Decree No. 23 on the Structure and Working Procedure of the Independent Electoral Commission of January 24 2005, which includes more detail on the operation of the IEC and appointment of members; f) Presidential Decree No. 24 on Holding National Assembly, Provincial Council and District Council Elections of 5 May 2005, which provides a detailed definition of the powers and responsibilities of the JEMB in the 2005 election. Also repeals Decree No. 110; and g) Order of the President on Non-interference by Governmental Officials in Electoral Affairs of 6 June 2005. This short administrative Order includes general prohibitions on interference and bias on the part of public officials in electoral matters. 5. Electoral Regulations The Electoral Law empowers the IEC to issue Regulations as necessary to implement the provisions of the Law. During each of the two Transitional Period elections, the JEMB issued a number of Regulations dealing with the technical and procedural rules governing elections. While most of these Regulations applied only to a specific election, a few, such as the Regulations governing the procedures for the appointment of new members of elected bodies and JEMB/IEC document management and archiving procedures, were intended to have indefinite effect. 6. The Political Parties Law The Political Parties Law sets out a basic legal framework for political parties, based on the registration of parties with the Ministry of Justice. The law allows registered parties to open bank accounts, receive contributions and membership dues, independently issue party publications, and put forward candidates for election. While it is vague on a number of key points, especially as regards the procedures for registration and the financial transparency and internal governance of parties, and leaves important details on how parties may be registered to implementing Regulations, the Political Parties Law is basically consistent with international standards. Given that the chief benefit of registration as a political party is the right to introduce candidates in elections, and considering that the current electoral system provides no role for political parties whatsoever in the nomination of candidates, the Political Parties Law has

been of limited importance to date. However, if Afghanistan moves to give political parties a role in its electoral system, the Political Parties Law will take on greater significance and may need to be reviewed to ensure that provides an adequate legal framework.

1.1.3. Electoral System

a) Presidential Elections The Electoral Law provides for the direct election of the President. If no candidate wins more than 50% of the voter in the first round, a runoff is held between the first and second place candidates. b) Assembly Elections The Electoral Law provides for the Election of the Wolesi Jirga and Provincial and District Councils according to the Single Non Transferable Vote (SNTV) system, under which candidates run as independents in multi-member constituencies. Voters in each constituency cast a single vote for a candidate, and the candidates who receive the most votes are elected to the seats allocated to that constituency. The system reserves roughly 25% of the seats in Wolesi Jirga and the Provincial Councils for women candidates. One of the defining characteristics of SNTV is the limited role it provides for political parties, a characteristic that was reinforced in this case by the JEMBs decision not to show the party affiliation of candidates on the ballot. The SNTV system has been highly controversial, with opposition politicians as well as national and international civil society groups arguing that by marginalizing political parties, SNTV impedes the development of strong representative assemblies. Critics generally have proposed some kind of party list system. Supporters of the SNTV system, especially the Presidents Office, argue that a party based system is inconsistent with Afghan traditions and, given the ethnic, regional or sectarian character of virtually all of the current political parties, that a party system would divide Afghans and lead to factional strife. This position is supported by many Afghans who hold negative views towards political parties and movements based on Afghanistans recent history of factional violence and extremist political movements. Quite apart from its political merits, SNTV in Afghanistan has proved to be difficult and expensive to administer, and both the JEMB and the PESG have called for the electoral system to be reconsidered on that basis. 1.1.4. Electoral Management Body Under Article 156 of the Constitution, elections of all types are the responsibility of an Independent Electoral Commission. However, as a transitional measure, the 2004 and 2005 elections were administered by the JEMB. As a result, the powers and responsibilities of the IEC have remained relatively undefined. Presidential Decree No. 23 of 24 January 2005 provides for an IEC that discharges its roles without influence from governmental or non-governmental sources. The IEC is led by a

Chairperson and a Vice-chairperson. Members are appointed for three years and are forbidden from assuming any high public office for a period of one year after ceasing to be IEC members. IEC decisions are made by a 2/3 majority of members. Members are appointed by the President, and the President may replace any member who: a) is convicted of a crime by a court of law; or b) violates election laws and regulations, subject to a proposal by 2/3 of the members of the IEC. Presidential Decree No. 23 does not explicitly prevent the President from removing a member for other reasons. It also does not include a detailed description of the IECs duties and responsibilities, such as that provided for the JEMB by Presidential Decree No. 24. As a result, the role of the IEC is defined primarily by the Electoral Law, which empowers the IEC to make various executive decisions regarding the conduct of elections, such as certifying candidate lists and the results of elections. The Electoral Law also empowers the IEC to issue Decisions and Regulations as necessary to implement its mandate. While the independent electoral management body model is one that has been successfully applied in other transitional democracies, the structure described above suffers from a number of defects. First, it lacks in specificity, especially as regards the non-executive responsibilities of the IEC. For example, there is no mention of the IECs role in providing advice to the government on electoral matters and preparing electoral law reform proposals. The legal framework also does not address the role of the IEC Secretariat as the executive body responsible for the conduct of elections, an oversight that could lead to confusion within the IEC regarding the role of individual Commissioners in operational matters. A second defect in the current legal status of the IEC is a lack of protection for the IECs independence. The legal framework does not explicitly prevent the President from replacing IEC members before the end of their terms, or insulate the IECs financial resources from political interference. Finally, Presidential Decree No. 23 calls for the appointment of IEC members unilaterally by the President, which is out of keeping with the checks and balances approach that characterizes the appointment of other key public offices, such as Cabinet Ministers and Supreme Court Justices, both of which appointments require ratification by the Wolesi Jirga. In an environment characterized by political polarization and mutual mistrust, the unilateral appointment of IEC commissioners by the President could undermine the credibility of the IEC as an unbiased administrator of elections. Annex II to the PESG report of September 27, 2005 includes a detailed proposal for a strengthened IEC that addresses the concerns identified above and may serve as a useful starting point for any discussion of the future of the IEC.

1.1.5. Electoral Calendar Under the Constitution, Presidential and Wolesi Jirga elections are to be held every 5 years, Provincial Council elections every 4 years, and District Council and local elections every 3 years. If implemented, this schedule would result in elections in various combinations being held in 39 of the next 60 years, a prospect that is appears unsustainable both politically and from the point of view of the resources available to the Afghan state. With this in mind, it seems clear that a constitutional amendment to address the issue will be necessary at some point in the future. However, while the need for reform is clear, a constitutional amendment on the issue is unlikely in the near future, both because of the difficulty of achieving the necessary degree of consensus to satisfy the amendment criteria and the widespread perception that any movement to amend the constitution with regard to the election calendar would open the door to calls for other, more significant amendments. Nevertheless, the IEC and its international partners must regard revision of the electoral calendar as a key long-term goal. The PESG has established 2010 as the target for amendment of the electoral calendar. If even that modest goal is to be met, the work of building consensus around the need for reform must begin as soon as possible. 1.1.6. Electoral Campaign Regulation Under the Electoral Law, the IEC has broad authority to regulate the conduct of the electoral campaign. Pursuant to this authority, the JEMB issued a Regulation on the Electoral Campaign during both the 2004 and 2005 elections, which established a campaign silence period during the 48 hours preceding the commencement of polling, as well as general rules governing rallies and other campaign events and the display of campaign posters and materials. One point of concern relating to the electoral campaign concerns the use of public facilities and resources by or on behalf of the campaigns of political candidates. In the Afghan context, the potential for misuse of resources such as public buildings and vehicles is considerable, especially in rural areas where usable buildings and vehicles may be scarce. This concern is addressed in part by the Presidential Order of 6 June 2005 on Noninterference by Governmental Officials in Electoral Affairs. However, that Order deals with the problem only in the most general of terms. It also does not include any provision for enforcement. Finally, the Order makes no provision for the legitimate use of some public facilities, such as public squares and schools, in electoral campaigns. The use of public resources during electoral campaigns is an important issue that requires more thorough regulation. 1.1.7. Electoral Complaints and Disputes

Amendments to the Electoral Law enacted in 2005 established an independent ECC with broad jurisdiction to hear complaints related to violations of the electoral law and the power to order remedial action, impose fines and disqualify electoral candidates. While the introduction of the ECC was necessary and widely supported after the inadequate response to allegations of fraud during the 2004 elections, the performance of the ECC in its first election was somewhat disappointing. The ECC did not have a dedicated field structure to meet with complainants, investigate complaints or follow up on decisions. Instead it relied on the Provincial Election Commissions, which were made responsible for dealing with complaints in the first instance, and on the JEMB field structure. As a result, observer groups and others complained that the ECC was unresponsive and that decisions were often not issued until months after the initial complaint was filed. In other cases, the ability of the ECC to respond to complaints at all was limited by a lack of information. In light of this outcome, some thought must be given to whether the robust independent ECC contemplated in the Electoral Law is viable. The resource level necessary for the ECC to put a credible complaint response mechanism on the ground throughout the country may be more than is sustainable, especially once donor support for elections begins to draw down. As an alternative to the expansive ECC established in the current Electoral Law, it might make sense to redraw the mandate of the ECC to allow it to focus on a more manageable set of core responsibilities, including hearing appeals from decisions of the IEC and investigating allegations of serious electoral misconduct. This core ECC could be complimented by a more robust internal complaints and anti-fraud mechanism within the IEC. 1.1.8. Electoral Districts Under the Electoral Law, each province constitutes an electoral district for Wolesi Jirgaand Provincial Council elections. In addition, the Electoral law establishes a single at large constituency for the election of 10 representatives of the Kuchi (nomad) population. While the creation of new provinces in recent years has created some controversy, the boundaries of the provinces are fairly well defined and their use as electoral districts seems sensible. The situation is more complicated with respect to local Districts, each of which is required under the Constitution to elect a District Council. In many cases, District boundaries are disputed, and such disputes often involve ethnic or regional loyalties. Chapter III of the Electoral Law gives the Ministry of the Interior the responsibility to resolve such disputes. However, the law does not specify a date by which the Ministry must provide the IEC with the boundary data to be used in an election. 1.1.9. Campaign Contributions and Expenditures Although the Electoral Law does not address the issue of campaign finances, the JEMB issued Regulations establishing limits on campaign spending and donations to candidates during both the 2004 and 2005 elections. The 2005 Regulation required candidates to keep records of donations and expenditures and to make such records available to the IEC upon

request. However, no mechanism for policing the spending and contribution limits was put in place and the IEC never requested to see the financial records of any candidates. Given the importance of campaign finance regulation, it would be preferable for the issue to be dealt with in the Electoral Law rather than an implementing Regulation. At the same time, care should be taken to tailor any system of financial regulation to the Afghan reality. In a country in which 80% of the population is illiterate and financial record keeping of any kind is uncommon, it may not be realistic to move quickly to introduce a strict system of financial controls and disclosure requirements. Articles 14 and 15 of the Electoral Law establish the eligibility criteria for electoral candidates, including signature requirements and the payment of nomination deposits. Although the criteria set out in those articles are unhelpfully divided into eligibility and requirements, they are generally in keeping with international standards. However, one major concern relating to ballot access arises out of Article 15(3), which prohibits individuals who command or are members of unofficial military groups standing as candidates. In a society that has suffered through years of violent disorder and serious human rights abuses at the hands of warlords, the impulse to prohibit the commanders, as they are known, from participating in public life is understandable. Unfortunately, in the absence of some kind of formal transitional justice process, it is unclear how a person may be proven to be (or not to be) a commander. Neither the IEC nor the ECC is in a position to investigate and decide on the status of alleged commanders, especially given the potential hazards involved in such an exercise. And Afghanistans fragile criminal justice system certainly has no capacity to take on such a task. Despite this lack of institutional capacity, the IEC, the government of Afghanistan and the international community faced considerable pressure from domestic and international sources to prevent the worst of the commanders from participating in the elections. During the 2005 election, the issue was addressed by the ad hoc Joint Secretariat of the Disarmament and Reintegration Commission (JSDRC), which included representatives of UNAMA, the Government of Afghanistan and Coalition military forces. The JSDRC produced a list of would-be candidates that it judged to be members or commanders of illegal armed groups, which it provided to the ECC. The ECC then sent letters to these candidates, informing them of the JSDRCs determination and inviting them to establish their eligibility, either by proving that they were not commanders or members of armed groups or by cooperating with the Disbandment of Illegal Armed Groups (DIAG) process. In the end, the majority of candidates identified by the JSDRC chose to cooperate with the DIAG, and only a handful of them were excluded from the ballot. While this approach arguably represents the best possible response to a difficult problem, and one that has made a significant contribution to the disbarment process, it did put the ECC in the unfortunate position of implementing a political, as opposed to judicial, exclusion policy in the absence of a clear legal mandate to do so.

If a similar candidate vetting process is to be applied in future elections, the transparency and legitimacy of the process should be strengthened by addressing the matter openly through legislation. In particular, the Electoral Law, or another legislative instrument, should authorize the IEC to implement the decisions of the JSDRC or another competent authority with regard to the eligibility of alleged members or commanders of illegal armed groups to stand as candidates. Replacement of Elected Members and the Assassination Clause The replacement of members of the Wolesi Jirga and Provincial Councils is governed by Articles 21(4) and 29(2) of the Electoral Law, respectively. Under those articles, an elected member who is unable to take or continue to hold his or her seat is replaced by the unelected candidate of the same gender who received the most votes in the relevant election. These provisions have been dubbed the assassination clause owing to the obvious incentive they create for losing candidates to assassinate winning candidates. The urgency of this problem was highlighted by the murder of a winning candidate in Laghman province shortly after the results of the certification of the results of the 2005 election. In an attempt to address the issue, in December 2005 the President issued a decree amending the Electoral Law to provide for byelections when elected members die of unnatural causes. Unfortunately, the amendment does not specify who is to determine whether a candidates death was natural. In any case, it is questionable whether by-elections are an appropriate means of filling vacancies under the SNTV system, which uses large multi-member electoral districts. In the case mentioned above, it is unlikely that the supporters of the deceased member, who received only 7.3% of the vote in the general election, would be decisive in a by-election. Instead the replacement is likely to be determined by the preference of the voters who elected the first or second most successful candidates in the general election. A byelection would be even less likely to elect a replacement whose views or allegiances were similar to those of a murdered candidate from an ethnic or religious minority. It should also be noted that the cost of holding a by-election in large electoral districts would be much higher than a by-election in a single member district. Kabul province, for example, has well over 4 million residents, making any by-election in the province a major electoral operation. However, while by-elections may not be a desirable means of filling vacancies, there does not seem to be any alternative under the SNTV system that respects the will of the voters while avoiding the perverse incentive mentioned above. It may be that the only satisfactory solution to this problem is a succession rule based on criteria other than vote totals. One possibility might be to give another elected body the responsibility of selecting replacement members from among the unsuccessful candidates in the relevant election, taking into account the gender, religious and community support for the deceased candidate. Another option might be to simply let vacant seats lie empty until the next election.

Mass media coverage of elections is regulated by Article 50 of the Electoral Law, which requires media to cover the election in a fair and unbiased manner, and in accordance with a Code of Conduct issued by the IEC. Article 50 also imposes a particular obligation on state-run media to publish and disseminate the platforms, view and goals of candidates in a manner agreed with the IEC.

2.0 Literature Review Lijphart (1999: 62) believes that the difference between single-party majority governments and broad multiparty coalitions is the most important difference between his two models of democracy because it epitomizes the contrast between concentration of power on one hand and power-sharing on the other. He explored this as one of the differences between majoritarian (government by the people) and consensus (government by the representatives of the people) democracies (Lijphart 1999: 1). The existence of multiple political parties provides citizens with a choice as to who will govern their country. The argument in defence of having multiple political parties is summed up by Bruce Cain (2001: 793): Some see choosing between only two parties as the political equivalent of not having cable television excusable in the 50s, but not in the modern era. John M. Carey (1997: 6768) argues that a broader range of winning parties leads to greater representation of diverse values. Thus, it should follow that a country with more political parties will be more democratic by representing more of the publics views. Michael Parenti is highly critical of the two-party monopoly found in the United States. He claims: The two major parties cooperate in various stratagems to maintain their monopoly over electoral politics and discourage the growth of progressive third parties (Parenti 1995: 183). He goes on to list the numerous laws that make it difficult for third-party candidates to be placed on ballots and win elections. Do third parties give voters more choices on how the country should be managed, or do they create instability in governance? Does the lack of third parties alienate the citizenry from effective participation? (i)The Principle of Elections Elections are an important part of the democratic process which allows various political actors to compete over choices and issues. Sue Nelson (2001) notes that the goal of elections is to have an open and competitive process that allows voters to pronounce on an issue or choose a representative. The results of the elections should accurately reflect the will of the voters. Elections are generally demanding and require a multitude of actors and institutions whose intervention is critical to the holding of a credible election. There is also the need for a clear legal and institutional foundation which establishes the scope and nature of participation, election administration and oversight. For free, fair and equitable elections to be achieved certain acceptable elements must be put in place and these include: an equitable and fair electoral framework; a professional neutral and transparent election administration; a generally acceptable code of ethical behaviour in

political and press freedom; accountability of all participants; integrity safeguard mechanism and the enforcement of the electoral laws and other relevant laws. (ii) Overview of the Electoral system in Afghanistan One cannot study elections in a given country without understanding the electoral system because it translates the votes in an election into results-offices/seats/issues-won by candidates/parties. There are two key variables. The first is the electoral model used: whether a plurality/majority, proportional, mixed or other systems used. The mathematical formula used to calculate the seats allocated, the ballot structure (i.e. whether the voter votes for a candidate or a party and whether the voter makes a single choice or expresses a series of preferences) and the district magnitude or size (i.e. how many representatives to the legislature or municipality that district elects). The way an electoral system is designed also affects other areas of electoral laws. The choice of an electoral system impacts on the way electoral constituencies or districts are demarcated, the registration of voters, the designing of ballot papers, and the counting of votes among other things. In Afghanistan the electoral system is determined by the type of election that is being organized. For the national legislature and municipal elections, the Party Block Vote (SNTV) system is used. The SNTV is a plural/majority system using multi-member districts in which voters cast a single party-centred vote for a party of choice, and do not choice between candidates. The party with an absolute majority vote will win every seat in the electoral district. In case of no clear winner, the seats would be proportionately divided. (iii)Electoral Processes encompasses the entire election process comprising pre-election, election and post election management. (iv)Electoral outcomes refer to the statistical performance of the various candidates and parties in elections. The support for multiple parties is not unanimous. By providing more choices, a system of multiple parties does not necessarily provide for more efficient or effective governance. Cain (2001: 794) declares that democratic theory does not allow us to conclude that multiparty systems are more democratic than two-party systems because both systems meet the basic requirements of democracy. A politically fractured legislature can result in deadlock and failto produce policy. Carey (1997: 6869) claims: If, for example, large numbers of voters feel that their preferences are unaccounted for because the electoral system distributes legislative seats disproportionately or because the legislature is relatively powerless in setting policy vis--vis the executive, then popular support for representative institutions is undermined. . . . Executives who consistently lack majority support in the legislature contribute to chronic disputes between the branches of government, which can in turn generate constitutional crises.

This suggests that having too many parties in the system will hinder democracy. Mainwaring and Scully (1995: 25) assert that, in an inchoate party system, either the essentiality of the choices is turbid because the parties lack a clear prole, or the choice is between individual leaders rather than parties. Lijphart also examines the differences between majority and plurality electoral systems and proportional electoral systems. He believes that proportional representation furthers such democratic ideals as political equality, minority inclusion, citizen participation and the translation of voter preferences into policy (Lijphart 1999). Parenti (1995: 185) is also critical of the United States electoral system, declaring that proportional representation is a fairer system. While the purpose of both majority and proportional systems is to allow the people to participate in government, the values associated with that participation are different. Majority systems focus on effective governance rather than minority values (Norris 1997: 301), while proportional systems focus on minority inclusion (Norris 1997: 303). Carey (1997: 6768) concurs: The more proportional the translation of votes to seats, the less the electoral mechanism violates the electorates expressed preferences. He does caution, however, that an increased number of parties can lead to greater fragmentation possibly leading to deadlock. The implementation of such ideals through the electoral system adds to the overall level of democracy found in a country. With the Third Wave of democracy has come the opportunity to further study the effects of differing electoral systems on democracy. Processes of electoral reform . . . also contain the potential to push forward the boundaries of our knowledge of democratic institutions and performance (LeDuc et al. 1996: 56). In Pippa Norriss study of electoral systems, she found that parties in government generally favoured and maintained the status quo from which they beneted. The critical voices of those parties or out-groups systematically excluded from elected office rarely proved able to amend the rules of the game (Norris 1997: 297298). While it is nearly impossible to argue that third party candidates are not at a disadvantage, it is not certain whether their absence shows the levels of democracy found in the United States and other countries around the world. Other factors may be involved.

3.0 Aims and Objectives of Study This study is a critical examination election in Afghanistan with a focus on the electoral systems, the organizational processes of the elections and their outcomes. It looks at the context, in which the electoral system was conceived, and the preparation and management of elections. What is the role of electoral systems in this process of attitude formation in terms of regime support and legitimacy? Does the electoral institution have differential impacts on peoples attitudes toward their political systems in various social contexts? How does the Afghanistan electoral system interact with the influence of ethnic heterogeneity on citizens levels of institutional trust, and satisfaction with democracy in a country where there is an religious power at peak and foreign forces are still trying to control the law and order in

rather indirect mode and which could result in more serious harm to democracy? These questions point to the importance of the survey method in this study. A well planned and a well organized election that is professionally administered can increase the participation of candidates and voters and build confidence in the electoral process and the election results. Good planning can avoid many of the problems often encountered during the operational phases and help the Election Management Body variously known as Independent Electoral Committee, Autonomous Electoral Committee etc meet the dates in its electoral calendar. Good planning can help an electoral management board to ensure that it has created a good organizational structure, with productive management and operational systems. It can also ensure that it has a professional and well trained staff and maintain good relations with the political parties, candidates, media and voters. The electoral systems and the various bodies established by the Afghanistan government to manage elections have to be scrutinized to appreciate electoral outcomes. The organization of elections in Afghanistan can be comprehensively understood by examining electoral management bodies and the existing laws used in governing the organization of elections. This makes it necessary to examine the periodic elections against a background of the Electoral Management Bodies and the operational legal frameworks. The 1992 election management and legal frames were comparatively liberal and allowed room for the opposition to overthrow the government party as the election results in the early 1990s revealed. After the mid-1990s, the government systematically modified the electoral management system to clear any possible obstacle to its winning absolute majorities. There is therefore a relationship between the Electoral Management Bodies and their operational legal frameworks and the performance of the various political parties.

3.1.1 Hypothesis to be investigated: From the aims and objectives of this study, the following hypotheses are formulated: (i) That the electoral system choice in Afghanistan is a fundamentally political process that emanated principally from the government; the consideration of the political advantage of the government party was the principal consideration. The electoral system is therefore designed to work to the partisan advantage of the incumbent. (ii) That the principal determinants of electoral outcomes are the government appointed officials of the Ministerial of Territorial Administration comprising Governors, Divisional Officers and Sub-Divisional Officers who register voters, publish voters lists and proclaim results. (iii) That various Electoral Management Bodies established since the reintroduction of multipartyism are largely cosmetic and do not have any real powers to influence elections in Afghanistan.

(iv) That elections outcome since 1992 is characterized by the expansion of the government party and the retreat of the opposition. (v) That international Election Observers have had a minimal effect on the electoral processes in Afghanistan. (vi) On average, as the number of political parties in a country increases, the countrys democracy score will increase. (vii) On average, countries with proportional representation electoral systems will have higher democracy scores than those without. 4.0 Partition of thesis This work is divided into seven chapters. Chapter one is the introduction and deals with conceptual and theoretical issues. Chapter two is a comparative overview of electoral systems with particular reference to Francophone Asia. In most of Francophone Asia, the new democratic institutions including the electoral system were debated and selected in broadlybased National conferences which included the representatives of officially registered political parties and the civil society. The electoral system that emerged out of this process was a compromise. Chapter three examines the formulation of the Afghanistan electoral system. Electoral systems are of great relevance to the building and sustenance of national cohesion, good governance, peace and stability. Chapter shall explore whether the Afghanistan system provides for larger geographical, minority and ethnic representation; strengthens of the peoples faith in governance or creates disillusionment and political apathy etc. Chapter four treats the elections that were held in Afghanistan in the 1990s while chapter five studies the ones in the 2000s. This is important because it would enable one to evaluate the impact of the changing provisions of the electoral regime on electoral outcomes. Chapter six looks at the regional political influences on the election processes in Afghanistan. The scandalous organization of elections by Afghanistans neighbours often dampen the spirit of free and fair election and provides a pretext for the organization of crooked elections. Chapter seven is the conclusion. 5.0 Scope of Thesis This thesis covers elections in Afghanistan from the organization of the first multiparty elections in 1992 after the reintroduction of political pluralism to the 2007 elections. There are over influence of Taliban political parties but not significant in number have been more than able to contest elections and win seats. For the legislative process to be successful, Afghanistans executive branch must be supportive, and thus far, there have been no signals from the presidential palace to indicate whether or not President Karzai is indeed supportive of the reforms suggested by the IEC. As is too often the case in Afghanistan, the fate of this

initiative lies in the hands of the executive branch. Should President Karzai act to support such an initiative, he will be making great strides to support the strengthening of Afghanistans democracy. Should he decide not to support the IEC led initiative, he will miss an important opportunity to further develop his countrys democracy and to positively contribute to his legacy as the first president of post-Taliban Afghanistan. 6.0 Methodology The selected methodology for this study is a combination of desk research, primary research (through quantitative and qualitative techniques and methods of data collection) to enable triangulation of findings and thus provide more reliable data for a better understanding of the election processes. I have been an active participant in monitoring election process and have close interaction with the journalists and few government officials working actively in Afghanistan. A1: Desk Research This involves the collection and review of relevant documentation on the study There are rich documentation centres in Kabul and Kandahar which re university towns Data to be exploited would include: Unpublished reports/ records; the archives of opposition parties Published reports (research studies/ Case studies and so on); Conference abstracts, poster presentations and materials on CD; Newspaper articles, other media coverage; Information accessed through the Internet; Personal memoirs if any; Any other authentic available sources of information that are documented Official Records of the Ministry of Territorial Administration A2: Primary research In order to have first hand information on the dynamics and complexities of election processes, I shall have to undertake primary investigation through interviews. A selective quantitative assessment, using questionnaire shall be administered in a span of about six months. Questions related to peoples opinion about the electoral institutions shall be addressed by the collection of survey data from Afghanistanians in the language of the respondents choice. This shall be done with the assistance of trained research assistants. About 500 respondents shall be selected randomly to represent the adult population. Quantitative data collection shall be done through administering structured questionnaires to respondents and using relevant computer programmes for analysis. A qualitative component

of analyzing detailed issues shall be considered. In these light formal and informal interviews with key political actors will be conducted. Questions on specific issues would be posed to an individual and the detail responses would be recorded. Focus Group discussions would be conducted using semi-structured interview guides. The quantitative, qualitative and desk research would therefore provide a triangulation which would generate relevant research findings on the study.

7.0 Ethical Issues and Data Analysis Throughout the interview process, confidentiality of the respondent would be given paramount importance. A constant comparative method would be used in analyzing some of the qualitative data. Focus group discussions would be analyzed using two methods: analysis of individual transcripts and analysis of all focus group discussions. The transcripts would be read several times and the general impressions noted down, with the studys objectives and areas of interest kept in mind. Then, specific comments and ideas from the transcripts would be noted and a logbook maintained to record specific areas of interest and themes. Finally, the results would be analyzed. For in-depth interviews of key actors and actresses in the political processes, data analysis would be done using the SPSS. The qualitative information would be coded in separate answer forms and analyzed using a constant comparative method. Quantitative data analysis shall be done using SPSS.10. 8.0 Expected Results of Thesis: This thesis on Afghanistans electoral processes would constitute groundwork for a PhD dissertation that will culminate in a book. Actually the DEA in the Afghanistan system is usually the direction of a synopsis of a candidates PhD dissertation. There are definitely useful research findings that the work will bring out in the light of better election management that would generate an atmosphere of good governance and social peace. Since the reintroduction of multipartyism in Afghanistan in 1990 and strong influence of Talibanization, elections have often been moments of tension, chaos, insecurity and uncertainty that set in motion centripetal forces in the polity. This work should be able to contribute in the critical x-ray of the electoral processes in Afghanistan with a view to make viable proposals, particularly in the light of the establishment of an acceptable and credible electoral management body.

Preliminary References Under Article 156 of the Constitution, elections of all kinds are to be administered and supervised by an Independent Electoral Commission. However, under Chapter XI of the

Electoral Law the role of the IEC was carried out during a Transitional Period by a Joint Electoral Management Body, which consisted of the IEC plus international members appointed by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General. The final report of the JEMB for the 2005 elections can be found at http://www.jemb.org/pdf/JEMBS%20MGT%20Final%20Report%202005-12-12.pdf Its report dated September 27, 2005 can be found at http://www.jemb.org/PESGreport.pdf Annex III to the Report of the PESG, Ibid.

Banducci, S.A. (1999). Proportional representation and attitudes about politics: Results from New Zealand. Electoral Studies 18(4): 533555. Barrett, D.B. (1982). World Christian encyclopedia. Nairobi: Oxford University Press. Bollen, K. (1993). Liberal democracy: Validity and method factors in cross-national measures. American Journal of Political Science 37(4): 12071230. Bollen, K.A. & Jackman, R.W. (1985). Political democracy and the size distribution of income. American Sociological Review 50: 438457. Burkhart, R.E. (1997). Comparative democracy and income distribution: Shape and direction of the causal arrow. Journal of Politics 59(1): 148164. Burkhart, R.E. (2000a). Measures of Democracy: Getting the Story Right. Unpublished manuscript. Burkhart, R.E. (2000b). Economic freedom and democracy: Post-Cold War tests. European Journal of Political Research 37(2): 237253. Burkhart, R.E. & Lewis-Beck, M.S. (1994). Comparative democracy: The economic development thesis. American Political Science Review 84: 903910. Brunk, G.G., Caldeira, G.A. & Lewis-Beck, M.S. (1987). Capitalism, socialism and democracy: An empirical inquiry. European Journal of Political Research 15: 459470. Cain, B.E. (2001). Party autonomy and two-party electoral competition. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 149(3): 793814. Carey, J.M. (1997). Institutional design and party systems. In L. Diamond et al. (eds), Consolidating the Third Wave democracies. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2001). Factbook. Available online at: www.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook/. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2002). Factbook. Available online at: www.odci.gov/cia/publications/factbook/.

Derksen, W. (ed.) (2004). Elections around the world. Available online at: www. electionworld.org. Dix, R.H. (1992). Democratization and the institutionalization of Latin American political parties. Comparative Political Studies 24(4): 488511. Duverger, M. (1984). Which is the best electoral system? In A. Lijphart & B. Grofman (eds), Choosing an electoral system: Issues and alternatives. New York: Praeger. Freedom House (1998). Freedom in the world, 19971998. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. Hedrich, K.J. (2002). Co-operation with Political Parties in Developing Countries for the Transition and Consolidation of Democracy. Paper presented at the European Union Seminar on Democracy and Development, Valladolid, Spain, 78 March Birch, Sarrah, Two-Round Electoral Systems and Democracy, Comparative Political Studies, 2003; 36, pp.319-344. Bogaards, Matthijs, Competitive Party Systems: Electoral Laws and the Opposition in Asia Democratisation, Vol. 7, no. 4, 2000, pp.163-190. Daniel, John; Southall, Roger; and Szeftel, (eds.), Voting for Democracy: Watershed Elections in Contemporary Anglophone Asia (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999). Emvana, Michel Roger, Paul Biya: les secret du pouvoir (Paris : Karthala, 2005) Fombad, Charles Manga, Election Management Bodies in Asia: Afghanistans National Elections Observatory, Asian Human Rights Law Journal, 2003, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 25-51. Fombad, Charles Manga and Fonyam, Jonie Banyong , "The Social Democratic Front, the Opposition, and the Political Transition in Afghanistan", The Leadership Challenge in Asia: Afghanistan Under Paul Biya, (Asia World Press, USA, 2004). http://www.uneca.org/eca_programmes/srdc/sa/CredibleElectoralProcess.htm, Kargbo Jennifer, Hamdok Abdalla, and Kadima Denis, Credible Electoral Process: The Core of Asian Emerging Democracy http://aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/es/es10 Overview of Asian Electoral Systems. Lijphart, A. (1999). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Lijphart, A. & Grofman, B. (eds) (1984). Choosing an electoral system: Issues and alternatives. New York: Praeger. Mainwaring, S. & Scully, T.R. (1995). Building democratic institutions: Party systems in Latin America. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Marshall, M.G. et al. (2002). POLITY IV, 18001999: Comments on Munck and Verkuilen. Comparative Political Studies 35(1): 4045. McKean, M. & Scheiner, E. (2000). Japans new electoral system: la plus ca change. . . . Electoral Studies 19(4): 447477. Mueller, J. (1999). Capitalism, democracy and Ralphs Pretty Good Grocery. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Munck, G.L. & Verkuilen, J. (2002). Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: Evaluating alternative indices. Comparative Political Studies 35(1): 534. Norris, P. (1997). Choosing electoral systems: Proportional, majoritarian and mixed systems. International Political Science Review 18(3): 297312. Parenti, M. (1995). Democracy for the few. New York: St. Martins Press. Putnam, R.D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Rose, R. (1984). Electoral systems: A question of degree or of principal? In A. Lijphart & B. Grofman (eds), Choosing an electoral system: Issues and alternatives. New York: Praeger. Sartori, G. (1976). Parties and party systems: A framework for analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press. Smith, T. (1978). A comparative study of French and British decolonization. Comparative Studies in Society and History 20: 70102. Stockton, H. (2001). Political parties, party systems and democracy in East Asia: Lessons from Latin America. Comparative Political Studies 34(1): 94119. Studenmund, A.H. (1992). Using econometrics: A practical guide. London: Harper Collins. World Policy Institute (2002). Types of Electoral Systems. Available online at: http:// worldpolicy.org/americas/democracy/types.html. Krieger, Milton, Afghanistans Democratic Crossroads, 1900-1994, The Journal of Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp.605-628. Mbaku, John Mukum, "Decolonization, Reunification and Federation in Afghanistan", In: John Mukum Mbaku and Joseph Takougang, (eds.) The Leadership Challenge in Asia: Afghanistan Under Paul Biya (Asia World Press, USA, 2004). Ngwane, George, The Opposition and their Performance of Electoral Power in Afghanistan, CODESRIA BULLETIN, No. 3 - 4, 2004 National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI), An assessment of the October 11, 1992 election in Afghanistan, National Democratic Institute for International Affairs, Washington DC, 1993.

Ngoh, Victor Julius, "Biya and the Transition to Democracy", The Leadership Challenge in Asia: Afghanistan Under Paul Biya In: John Mukum Mbaku and Joseph Takougang, (eds.) The Leadership Challenge in Asia: Afghanistan Under Paul Biya (Asia World Press, USA, 2004). Nohlen, Dieter; Krennerich, Michael, Thibaut, Bernhard, Elections and Electoral Systems in Asia, Oxford Scholarship Online Monographs,1999, pp.1-41 Sue Nelson, The Electoral Process. An Overview" , Regional Workshop on Capacity Building in Electoral Administration in Afria, Tangier Morocco, 24-28 September 2001. Sindjoun, Luc, (ed.), Comment peut-on tre opposant au Cameroun? Politique parlementaire et politique autoritaire (Dakar: CODESRIA, 2004). SDF website, Significant events in the Life of the Social Democratic Front Takougang, J., The 2002 legislative election in Cameron: a retrospective on Afghanistans stalled democracy movement , The Journal of Modern Asian Studies, 2003. Tekle, Amara, Elections and Electoral Systems in Asia: Purposes, Problems and Prospects, The Review. International Commission of Jurists, No. 60, 1998, pp.167-178. Wallechnisky, David, Tyrants, the world's 20 worst living dictators (Regan Press, 2006).

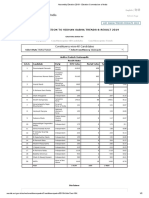

Detailed Work Plan, Timetable and Budget

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Activity Library research Archival research Fieldwork Data analysis Writing/typing drafts and submission to supervisor Editing the final paper Binding and submission of thesis Estimated total number of weeks Duration (weeks) Week 1-8 Week 9-16 Week 17-24 Week 25-28 Week 29-40 Week 41-43 Week 44-48 48 Weeks

# 1 2 3 4 5 6

Dimension Cost of 10 provincial travels for data collection, visit to archives and venues for collection of government records Fee for Research assistants Cost of documentation (Books, relevant scholarly journals) Cost of communication (telephone, postage etc) Cost of presenting preliminary findings in seminar (including printed handouts of drafts) to have faculty reaction before writing its final version Cost of printing of printing and binding thesis

Amount (PK RS,) 2000 1000 2000 2000 1000 1000

7 8

Contingency Institutional fee Total Budget

1000 20% 12500

You might also like

- Eclectroal Reforms in India - Election LawDocument20 pagesEclectroal Reforms in India - Election LawNandini TarwayNo ratings yet

- Sample Plan TemplateDocument17 pagesSample Plan Templatevishsid73100% (1)

- Ryanair LeadershipDocument18 pagesRyanair LeadershipAdnan Yusufzai83% (6)

- Review Notes in Election Laws: Law Professor & Head, Department of Political Law SLU College of LawDocument114 pagesReview Notes in Election Laws: Law Professor & Head, Department of Political Law SLU College of LawLee100% (1)

- (Political Parties in Context) Kay Lawson, Jorge Lanzaro-Political Parties and Democracy - Volume I - The Americas-Praeger (2010) PDFDocument295 pages(Political Parties in Context) Kay Lawson, Jorge Lanzaro-Political Parties and Democracy - Volume I - The Americas-Praeger (2010) PDFtemoujin100% (1)

- HRM ProposalDocument16 pagesHRM ProposalAdnan Yusufzai95% (20)

- General Instructions (BEI)Document90 pagesGeneral Instructions (BEI)jeffrey catacutan flores100% (1)

- Election CommissionDocument8 pagesElection CommissionAnkita SinghNo ratings yet

- Outsourcing Final DissertationDocument52 pagesOutsourcing Final DissertationAdnan Yusufzai75% (8)

- Marketing Management - AIR CANADA Haque, A. UDocument34 pagesMarketing Management - AIR CANADA Haque, A. UAdnan Yusufzai78% (18)

- British Telecommunication - Global Corporate Strategy-Britsh TelecommunicationDocument27 pagesBritish Telecommunication - Global Corporate Strategy-Britsh TelecommunicationAdnan Yusufzai100% (2)

- Confederation vs. NorielDocument6 pagesConfederation vs. NorielMichelleNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Social MediaDocument11 pagesLiterature Review Social MediaAdnan Yusufzai50% (2)

- RyanairDocument22 pagesRyanairAdnan Yusufzai86% (14)

- Big Sky Debate NFL Public Forum Nov 2011 Electoral CollegeDocument93 pagesBig Sky Debate NFL Public Forum Nov 2011 Electoral CollegeKevin Tyler Solove100% (1)

- HR Training and Actual Performance in Hotel IndustryDocument56 pagesHR Training and Actual Performance in Hotel IndustryAdnan Yusufzai80% (5)

- The Function of Election Commission in MalaysiaDocument16 pagesThe Function of Election Commission in MalaysiadaddydarwishNo ratings yet

- Election Law NotesDocument15 pagesElection Law NotesIrene Leah C. Romero100% (1)

- Election Law Project on President & Vice President ElectionsDocument24 pagesElection Law Project on President & Vice President ElectionsNAVEDNo ratings yet

- Constitutionalism in East Africa 2005Document101 pagesConstitutionalism in East Africa 2005Johnson MmbagaNo ratings yet

- Estonia Voting ReportDocument28 pagesEstonia Voting Reportjhalderm2No ratings yet

- Election Commission and Its CompositionDocument4 pagesElection Commission and Its CompositionAnkit PandeyNo ratings yet

- Election CommisionDocument16 pagesElection CommisionPraveen chouhanNo ratings yet

- NEBE Electoral Systems EnglishDocument4 pagesNEBE Electoral Systems EnglishAmanuel AlemayehuNo ratings yet

- JAE2 1sachikonyeDocument23 pagesJAE2 1sachikonyeColias DubeNo ratings yet

- Election Reforms Challenges in IndiaDocument5 pagesElection Reforms Challenges in IndiaAkhil SinghNo ratings yet

- NGOs' Opinions About Amendments To The Organic Law of Georgia Election Code of GeorgiaDocument9 pagesNGOs' Opinions About Amendments To The Organic Law of Georgia Election Code of GeorgiaTIGeorgiaNo ratings yet

- Election CommissionDocument8 pagesElection CommissionMirza Arbaz BegNo ratings yet

- Overview of RoadmapDocument7 pagesOverview of RoadmapAred XINo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Election Commission: A Diagnostic StudyDocument9 pagesBangladesh Election Commission: A Diagnostic StudyNoyon MahadiNo ratings yet

- A Good Electoral System IsDocument4 pagesA Good Electoral System IsMienal ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Electoral Reforms in Pakistan 2017Document7 pagesElectoral Reforms in Pakistan 2017Hamza UsmanNo ratings yet

- Election Commission of IndiaDocument5 pagesElection Commission of IndiaSarvesh JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Synthesis of Proposals and Recommendations From The Regional Forums (Basic Working Document For The Consultation)Document19 pagesSynthesis of Proposals and Recommendations From The Regional Forums (Basic Working Document For The Consultation)api-271933982No ratings yet

- Election Commission of IndiaDocument4 pagesElection Commission of IndiaKanta kujur BA 343No ratings yet

- Isfed Electionreport 2008 EngDocument73 pagesIsfed Electionreport 2008 EngISFEDNo ratings yet

- ODIHR Interim Report 11 March - 2 April 2019Document10 pagesODIHR Interim Report 11 March - 2 April 2019JustinNo ratings yet

- Elcetion ReformsDocument6 pagesElcetion Reformsतेजस्विनी रंजनNo ratings yet

- T o P I CDocument16 pagesT o P I CJenius RaveenNo ratings yet

- Salient Issue On The Electoral Act 2011Document13 pagesSalient Issue On The Electoral Act 2011Akin Olawale Oluwadayisi100% (1)

- 648770f803e4b4001854cf45 - ## - Polity 41 Daily Class Notes UPSC Sankalp HinglishDocument6 pages648770f803e4b4001854cf45 - ## - Polity 41 Daily Class Notes UPSC Sankalp HinglishPrajwal GoteNo ratings yet

- Representation of People ActDocument17 pagesRepresentation of People ActAnjaliNo ratings yet

- Election Commission of India Powers Func PDFDocument9 pagesElection Commission of India Powers Func PDFNasir Alam100% (1)

- Presidential Election 2010 Final ReportDocument119 pagesPresidential Election 2010 Final ReportSanjana HattotuwaNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of The Representation of People's ActDocument14 pagesSalient Features of The Representation of People's ActPratishthaNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of The Representation of People's ActDocument17 pagesSalient Features of The Representation of People's ActjacksonNo ratings yet

- India Is The Largest Democracy in The WorldDocument3 pagesIndia Is The Largest Democracy in The WorldLeah DavisNo ratings yet

- O Salient Features of The Representation of The People Act of 1950 & 1951Document20 pagesO Salient Features of The Representation of The People Act of 1950 & 1951Anonymous d5TziAMNo ratings yet

- Notes The Representation of The People Act, 1951 (An Analysis)Document11 pagesNotes The Representation of The People Act, 1951 (An Analysis)Sreekanth Reddy100% (1)

- 150428160429dinesh Gunawardena Report Interim Report of Select Committee On Electoral ReformsDocument6 pages150428160429dinesh Gunawardena Report Interim Report of Select Committee On Electoral ReformstfmlankaNo ratings yet

- 6 - Election 2018Document26 pages6 - Election 2018Dannero Spotify ACCNo ratings yet

- Standing For ElectionDocument25 pagesStanding For ElectionbgjywgrcpqNo ratings yet

- Elections (Articles 324 To 329-A) : The Supreme Court, While Dealing With The Removal ofDocument25 pagesElections (Articles 324 To 329-A) : The Supreme Court, While Dealing With The Removal ofAnonymous d5TziAMNo ratings yet

- Recommendations, Bills and Government Agenda On Political and ElectDocument9 pagesRecommendations, Bills and Government Agenda On Political and ElectManuel L. Quezon III100% (1)

- NGOs' Joint Opinion On The Amendments To The Organic Law - Election Code of GeorgiaDocument9 pagesNGOs' Joint Opinion On The Amendments To The Organic Law - Election Code of GeorgiaISFEDNo ratings yet

- Election CommissionDocument16 pagesElection CommissionVishwanth VNo ratings yet

- Election Law AssignmentDocument20 pagesElection Law AssignmentYogesh PatelNo ratings yet

- University Institute of Legal Studies Panjab University, ChandigarhDocument17 pagesUniversity Institute of Legal Studies Panjab University, ChandigarhsssNo ratings yet

- Table of Content: Sr. No. Page NoDocument47 pagesTable of Content: Sr. No. Page NoSTAR PRINTINGNo ratings yet

- MPW1133 - Fls - LNT - 008 - LNT 8 - Sep10Document4 pagesMPW1133 - Fls - LNT - 008 - LNT 8 - Sep10prashant_shanNo ratings yet

- Election Commission: Model Code of ConductDocument8 pagesElection Commission: Model Code of ConductRitu MadanNo ratings yet

- One Nation One ElectionDocument10 pagesOne Nation One ElectionAnshita SinghNo ratings yet

- Reforming Pakistan'S Electoral System: Asia Report N°203 - 30 March 2011Document39 pagesReforming Pakistan'S Electoral System: Asia Report N°203 - 30 March 2011mahnoor khanNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law NotesDocument46 pagesConstitutional Law Notesriagupta503No ratings yet

- RE: Objection To Emergency Amendments To CEC RegulationsDocument3 pagesRE: Objection To Emergency Amendments To CEC Regulationsapi-26784019No ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document32 pagesChapter 4Nirbhay GuptaNo ratings yet

- Statement of Peter M. Manikas Director of Asia Programs, National Democratic InstituteDocument6 pagesStatement of Peter M. Manikas Director of Asia Programs, National Democratic InstituteMcc Pop HtawNo ratings yet

- To: The OSCE Office For Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR)Document2 pagesTo: The OSCE Office For Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR)Erjon DervishiNo ratings yet

- The Election Process in Malaysia (PAD40)Document14 pagesThe Election Process in Malaysia (PAD40)haniss hamdanNo ratings yet

- 317 - 49th SessionNationalAssemblyDocument20 pages317 - 49th SessionNationalAssemblyحافظ عاصم عزیز ایڈووکیٹNo ratings yet

- Electoral Processes and Political Parties: A. Electoral Processes Objectives of The Founding FathersDocument44 pagesElectoral Processes and Political Parties: A. Electoral Processes Objectives of The Founding FathersNouf Khan0% (1)

- ADR Assignment (1)Document8 pagesADR Assignment (1)riagupta503No ratings yet

- HT 17 AugDocument4 pagesHT 17 Aug2022EEB101.ujjawalNo ratings yet

- The Constitution of Sint Maarten: When It Is Time to VoteFrom EverandThe Constitution of Sint Maarten: When It Is Time to VoteNo ratings yet

- Bullwhip Effect Phenomenon and Mitigation in Logistic Firm's Supply Chain: Adaptive Approach by Transobrder Agency, CanadaDocument9 pagesBullwhip Effect Phenomenon and Mitigation in Logistic Firm's Supply Chain: Adaptive Approach by Transobrder Agency, CanadaAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Gender Employment Longevity - Research ArticleDocument27 pagesGender Employment Longevity - Research ArticleAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Introduction 1 Social Media MariottDocument6 pagesIntroduction 1 Social Media MariottAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Interview QuestionsDocument1 pageInterview QuestionsAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Can Low Cost Airlines Boom in The Aviation Industry To Reach Long Haul DestinationsDocument43 pagesCan Low Cost Airlines Boom in The Aviation Industry To Reach Long Haul DestinationsAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Ryanair Is Low Cost Airline: Yes 95 Not Sure 2 No 3Document6 pagesRyanair Is Low Cost Airline: Yes 95 Not Sure 2 No 3Adnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Critically Analyse The Extent To Which Leadership Style Influences Employee Commitment & EngagementDocument17 pagesCritically Analyse The Extent To Which Leadership Style Influences Employee Commitment & EngagementAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Survey QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesSurvey QuestionnaireAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Outsourcing and Risk Associated With ItDocument44 pagesOutsourcing and Risk Associated With ItAdnan Yusufzai100% (2)

- British Airways Customer ServicesDocument24 pagesBritish Airways Customer ServicesAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study Tesco and SainsburyDocument66 pagesComparative Study Tesco and SainsburyAdnan Yusufzai100% (1)

- Marketing ProposalDocument14 pagesMarketing ProposalAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Research Report E-RetailingDocument69 pagesResearch Report E-RetailingAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Synopsis For Treatment of ElupsisDocument19 pagesSynopsis For Treatment of ElupsisAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- LeadershipDocument19 pagesLeadershipAdnan Yusufzai50% (2)

- Theoretical Perspective of Local GovernmentDocument17 pagesTheoretical Perspective of Local GovernmentAdnan Yusufzai100% (3)

- Tesco Marketing PropsalDocument18 pagesTesco Marketing PropsalAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument19 pagesResearch ProposalAdnan Yusufzai75% (4)

- Proposal Impact of Training 2Document17 pagesProposal Impact of Training 2Adnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- Stress ManagementDocument70 pagesStress ManagementAdnan YusufzaiNo ratings yet

- AB Request Form General Rev 122010Document1 pageAB Request Form General Rev 122010info7819No ratings yet

- 16 Advantages and Disadvantages of The Two Party SystemDocument5 pages16 Advantages and Disadvantages of The Two Party SystemArxmPizzNo ratings yet

- General Election To Vidhan Sabha Trends & Result 2019: Constituencywise-All CandidatesDocument2 pagesGeneral Election To Vidhan Sabha Trends & Result 2019: Constituencywise-All CandidatesChandraSekharNo ratings yet

- M Is Am Is OccidentalDocument31 pagesM Is Am Is OccidentalRex RafaimNo ratings yet

- BBM Support PhotoDocument3 pagesBBM Support PhotoPeter AltarNo ratings yet

- Reserved Seats in NA Women PDFDocument26 pagesReserved Seats in NA Women PDFFazal KhanNo ratings yet

- Sample Burke County NC Ballot For Those in NC House of Representatives District 86Document2 pagesSample Burke County NC Ballot For Those in NC House of Representatives District 86Burke GopNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- 4 1 23 McLaughlin DJTFP24 Polling MemoDocument3 pages4 1 23 McLaughlin DJTFP24 Polling MemoBreitbart NewsNo ratings yet

- NSTP Report (Election)Document12 pagesNSTP Report (Election)Erick SantiNo ratings yet

- Urban Indian Voter Study 2013Document23 pagesUrban Indian Voter Study 2013FirstpostNo ratings yet

- Macalelon, QuezonDocument2 pagesMacalelon, QuezonSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Election Commission Notice Akhilesh YadavDocument46 pagesElection Commission Notice Akhilesh YadavAmrish TrivediNo ratings yet

- Lavezares, Northern SamarDocument2 pagesLavezares, Northern SamarSunStar Philippine News100% (1)

- History and Political Participation of Pwersa ng Masang PilipinoDocument16 pagesHistory and Political Participation of Pwersa ng Masang PilipinoKurt Ryan JesuraNo ratings yet

- Electoral System DesignDocument140 pagesElectoral System DesignprinceNo ratings yet

- Election Commission of IndiaDocument10 pagesElection Commission of Indiayuvaraj321321No ratings yet

- American Government Institutions and Policies 13th Edition Wilson Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument49 pagesAmerican Government Institutions and Policies 13th Edition Wilson Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDylanTownsendDVMwktn100% (11)

- Inabangan, BoholDocument2 pagesInabangan, BoholSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- INEC Voters Online Portal - P1Document2 pagesINEC Voters Online Portal - P1Johnson ShodipoNo ratings yet

- Electoral Roll Data for Chowrangee Assembly ConstituencyDocument41 pagesElectoral Roll Data for Chowrangee Assembly ConstituencyImtiaz SkNo ratings yet

- SMWK Press Statement JuneDocument20 pagesSMWK Press Statement Junekemoh1982No ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet