Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Party Next Tim by Ryan Lizza

Uploaded by

Gilson PuertaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Party Next Tim by Ryan Lizza

Uploaded by

Gilson PuertaCopyright:

Available Formats

A REPORTER AT LARGETHE PARTY NEXT TIMEAs immigration turns red states blue, how can Republicans transform their

platform? BY RYAN LIZZA NOVEMBER 19, 2012 Left: Paul Labbe and Donna Lozon at a Republican watch party on Election Day, in Sarasota. Photograph by Chip Litherland. Right: In Denver, Democrats celebrate as Barack Obama wins a second Presidential term. Photograph by Landon Nordeman. PRINTE-MAILSINGLE PAGE KEYWORDS THE REPUBLICAN PARTY; IMMIGRATION; IMMIGRATION REFORM; TEXAS; DEMOGRAPHICS; LATI NOS; HISPANICS When historians look back on Mitt Romneys bid for the Presidency, one trend will be clear: no Republican candidate ever ran a similar campaign again. For four de cades, from Richard Nixon to Ronald Reagan through the two Bush Presidencies, th e Republican Party won the White House by amassing large margins among white vot ers. Nixon summoned the silent majority. Reagan cemented this bloc of voters, ma ny of whom were former Democrats. Both Bushes won the Presidency by relying on b road support from Reagan Democrats. In that time, Republicans transformed the So uth from solidly Democratic to solidly Republican, and they held the White House for twenty-eight out of forty years. Last Tuesday, Romney won three-fifths of t he white vote, matching or exceeding what several winning Presidential candidate s, including Reagan in 1980 and Bush in 1988, achieved, but it wasnt enough. The white share of the electorate, which was eighty-seven per cent in 1992, has stea dily declined by about three points in every Presidential election since then. A t the present rate, by 2016, whites will make up less than seventy per cent of v oters. Romneys loss to Barack Obama brought an end not just to his eight-year que st for the Presidency but to the Republican Partys assumptions about the American electorate. Some interpretations of the election results by conservatives were particularly dark. Mary Matalin, the Republican commentator, wrote that Obama was a political narcissistic sociopath who leveraged fear and ignorance to win. On Tuesday evening, before the race was called, Bill OReilly, after acknowledging that the demographi cs are changing, offered the following explanation for an Obama victory: Its not a traditional America anymore. And there are fifty per cent of the voting public w ho want stuff. They want things. And who is going to give them things? President Obama. He knows it and he ran on it. Whereby twenty years ago President Obama w ould have been roundly defeated by an establishment candidate like Mitt Romney. The white establishment is now the minority. He added, Youre going to see a tremend ous Hispanic vote for President Obama. Overwhelming black vote for President Oba ma. But far from Fox News Channels newsroom in Manhattan and the insular world of the Beltways conservative commentariat, one significant element of the Republican Pa rty has for the past two years been grappling with and adapting to the demograph ic future that was so starkly revealed by last Tuesdays outcome. On Halloween, le ss than a week before Election Day, I rode with Ted Cruz, now the senator-elect from Texas, who was folded into the back seat of a Toyota Corolla as an aide dro ve him from San Antonio to Austin. Cruz, who has a thick head of pomaded, neatly combed hair, is a former college debate champion and Supreme Court litigator, a nd is a commanding public speaker. That morning, he had addressed a small crowd of employees eating Kit Kats and candy corn at Valero, a major oil refiner whose headquarters are in San Antonio. As he told the story of his fathers journey fro m Cuba to Texas, the room fell silent. Cruz, who is forty-one, eschews telepromp ters, instead roaming across the stage and speaking slowly and dramatically, wit h well-rehearsed sweeps of his hands. He is one of several political newcomers w ho offer hope to Republicans after a disappointing election.

FROM THE ISSUECARTOON BANKE-MAIL THIS In the car, sipping a Diet Dr Pepper while he talked about his background and di scussed the future of the Party, Cruz was more down to earth than his Herms tie a nd Patek Philippe watch suggested. He said that he had relaxed the previous even ing at his hotel by watching Cowboys and Aliens. It is every bit as stupid as it so unds, he said. But it actually has a really good cast. Cruz, a lawyer who was solicitor general of Texas from 2003 to 2008, combines a compelling personal biography with philosophically pure conservatism. He won his Senate primary in an upset, earlier this year, partly by adhering to the secure -the-borders mentality popular with most Texas Republicans. He promised to tripl e the size of the U.S. Border Patrol and to build a larger border wall than his opponent proposed. In January, when he is sworn in, he will become one of the mo st right-wing members of the U.S. Senate. A Tea Party favorite who also happens to be Hispanic, Cruz is viewed by many as a key figure in helping to transform t he Party. According to exit polls, Hispanics, one of the fastest-growing segment s of the U.S. population, made up ten per cent of the electorate, their highest share in American history, and Romney lost the Hispanic vote to Obama by a margi n of seventy-one per cent to twenty-seven per cent, the lowest level of support for a Republican since 1996. Cruz is a first-generation citizen. His father, Rafael, as a teen-ager in Cuba, fought alongside Castros revolutionaries against the dictatorship of Fulgencio Ba tista. He was jailed and beaten by the regime. My grandmother said that his suit, which had started out bright white, you couldnt see a spot of white on it, Cruz s aid. It was just stained with blood and mud, and his teeth were dangling from his mouth. Rafael left for the United States, and in 1957 started at the University of Texas on a student visa. He continued to support Castro. He learned English ve ry quickly and began going around to local Rotary Clubs and Kiwanis Clubs and sp eaking about the Revolution and raising money for Castro, Cruz said. He was a youn g revolutionary. He would get Austin businesspeople to write checks. When Castro came to power, in 1959, the elder Cruz quickly grew disillusioned. H is younger sister fought in the counter-revolution and was tortured by the new r egime. Rafael returned to Cuba in 1960 to see his family, and was shaken by what Castros Communist dictatorship had wrought. When my father got back to Austin, Cru z said, he sat down and made a list of every place hed gone to speak, and he made a point of going back to each of them and standing in front of them and saying, I owe you an apology. I misled you. I took your money and I sent it to evil ends. And he said, I didnt do so knowingly, but I did so nonetheless, and for that Im tru ly sorry. When I was a kid, my dad told me that story over and over again. To me, that always defined character: to have the courage to go back and apologize. Rafael made sure that his son entered politics from the opposite side of the pol itical spectrum. In high school, Ted became involved with a group known as the F ree Market Education Foundation, which introduced him to the writings of conserv ative economic philosophers such as Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, Frdric Basti at, and Ludwig von Mises. Cruz travelled to Rotary and Kiwanis groups in Texas a s his father had a generation earlier. But, instead of expounding on Castro, he competed against other teen-agers in speech contests; the contestants delivered twenty minutes of memorized remarks about free-market economics. He soon joined a spinoff group, the Constitutional Corroborators, and learned a mnemonic device for memorizing an abbreviated version of the Constitution, which he and other c lub members would write out on easels for lunchtime crowds of Rotarians or local political groups around Texas. By the time he graduated from high school, he ha d given several dozen speeches across the state. It was transformational, Cruz said. The two strongest influences on my life were th

at experience and the personal experience of my familys story and my fathers fligh t from Cuba. Cruz already has had a remarkably successful career in law and politics. He is t he first to point out that he has excelled at almost everything he has set out t o do: the early speech contests (I was one of the city winners all four years whe n I was in high school); academics (I was the first person from my high school eve r to go to any Ivy League college); his Princeton debate career (I was the No. 1 s peaker); his time at Harvard Law School (I was on three different law journals, wa s a primary editor of the Harvard Law Review, and an executive editor of the Har vard Journal of Law and Public Policy, and then a founding editor of the Harvard Latino Law Review); his clerkship, from 1995 to 1996, for Judge Michael Luttig (w idely considered the top conservative federal appellate judge in the country) and , from 1996 to 1997, for former Chief Justice William Rehnquist (he and I were ve ry, very close); his five and a half years as solicitor general (ended up over the years really winning some of the biggest cases in the countryyear after year aft er year); and his record of arguing nine cases before the Supreme Court (it is the most of any practicing lawyer in the state of Texas). Cruzs coming challenge is his biggest yet. As with other Hispanic Republicans ele cted recentlyNew Mexicos governor, Susana Martinez; Nevadas governor, Brian Sandova l; Senator Marco Rubio, of Floridahis last name and heritage, along with his cons ervative leanings, assure that Republicans will look to him to help lead them ou t of the demographic wilderness. He might even run for President in 2016. Though he was born in Canada, he informed me that he was qualified to serve. The Consti tution requires that one be a natural-born citizen, he said, and my mother was a U .S. citizen when I was born. As a senator from Texas, the largest and most important state in the Republican firmament, Cruz has a special role in the post-Romney debate. At the Presidentia l level, Texas has thirty-eight electoral votes, second only to California, whic h has fifty-five. It anchors the modern Republican Party, in the same way that C alifornia and New York anchor the Democratic Party. But, Cruz told me, the once unthinkable idea of Texas becoming a Democratic state is now a real possibility. If Republicans do not do better in the Hispanic community, he said, in a few short years Republicans will no longer be the majority party in our state. He ticked of f some statistics: in 2004, George W. Bush won forty-four per cent of the Hispan ic vote nationally; in 2008, John McCain won just thirty-one per cent. On Tuesda y, Romney fared even worse. In not too many years, Texas could switch from being all Republican to all Democr at, he said. If that happens, no Republican will ever again win the White House. N ew York and California are for the foreseeable future unalterably Democrat. If T exas turns bright blue, the Electoral College math is simple. We wont be talking about Ohio, we wont be talking about Florida or Virginia, because it wont matter. If Texas is bright blue, you cant get to two-seventy electoral votes. The Republi can Party would cease to exist. We would become like the Whig Party. Our kids an d grandkids would study how this used to be a national political party. They had Conventions, they nominated Presidential candidates. They dont exist anymore. At the headquarters of the Republican Party of Texas, in Austin, an observer fin ds it difficult to take Cruzs warning seriously. One wall of the waiting room is plastered with framed photographs of Republicans who hold statewide office in Te xas. Governor Rick Perrys face is in the center; surrounding him is the lieutenan t governor, the attorney general, the comptroller, various commissionerswhich are powerful positions in Texasand numerous judges. Every one of the twenty-seven st atewide offices is held by a Republican, as are both U.S. Senate seats and twent y-four out of thirty-six House seats. At the state capitol, across the street fr om the G.O.P. headquarters, Republicans control the State Senate and House. Texa

s is essentially a one-party state. But others share Cruzs alarm that this could quickly change. Steve Munisteri, the fifty-four-year-old chairman of the Republican Party of Texas, whose father was an Italian immigrant, grew up in Houston and has been involved in state Republi can politics since 1972, when Texas was solidly Democratic. Munisteri saw how ra cial politics transformed Texas, which gradually shifted from one party to the o ther when conservative white Democrats fled to the G.O.P. The exodus began in 19 64, the year President Lyndon Johnson, the former Texas senator, passed the Civi l Rights Act. There goes the South for a generation, he is said to have remarked, as he signed the bill into law. Texas was slower than the other Southern states to see its politics invert. When George H. W. Bush was elected to Congress from Houston, in 1966, he was one of only two Republicans in the House delegation. Jimmy Carter carried the state in 1976. But in 1978 Bill Clements became the states first Republican governor in a hundred and four years. A young operative named Karl Rove worked on his campaign and joined his administration as a top adviser. Clements was voted out of offic e four years later, but, with Rove at the helm of his next effort, he returned i n 1986. Since then, the state has become steadily more Republican. The election of the Democrat Ann Richards, who won the governorship in 1990 and served just o ne term before being defeated by Roves next gubernatorial candidate, George W. Bu sh, was something of a fluke. She had a narrow victory against a weak candidate, who, among other campaign missteps, made a joke about rape and during one encou nter refused to shake Richardss hand. In 2010, Munisteri, a lawyer who has had stints in real estate and as a color co mmentator for boxing matches, took over the state Party, winning the chairmanshi p from an establishment that had all but given up on appealing to Hispanics in t he methodical way that George W. Bush did as the states governor from 1995 to 200 0. Munisteri has the look that most political operatives seem to attain in middl e age: rumpled, and filled with nervous energy. Im a natural worrywart, he said. He was suffering from an allergy attack, and while fighting back a fit of coughi ng he searched through heaps of papers strewn behind his desk and handed me some charts that foretold the demise of the Republican Party, first in Texas and the n nationally. One graph showed four lines falling from left to right, measuring Republican voting trends in Texas. Look at that; itll show you the decline of the Republican Party over ten years, he said. Actually, there was a significant bump up in 2010, a gift from President Obama, who helped reverse the slide by energiz ing the Tea Party movement, but what frightened him was the downward slope of th e lines from 2000 to 2008. There were fewer and fewer white voters as a percenta ge of the electorate. If I say to you, your life depends on picking whether the following state is Demo crat or Republican, what would you pick? Munisteri asked. The state is fifty-five per cent traditional minority. Thirty-eight per cent is Hispanic, eleven per cen t is African-American, and the rest is Asian-American, and two-thirds of all bir ths are in a traditional minority family. And if I was to tell you that, nationw ide, last time, Republicans got only roughly four per cent of the African-Americ an vote and about a third of the Hispanic vote, would you say that state is Demo crat or Republican? Well, thats Texas. We are the only majority-minority state in the union that people consider Republican. Immigration from Mexico only partly accounts for the change. More than a million Americans have moved to Texas in the past decade, many from traditionally Democ ratic states. More than three hundred and fifty thousand Californians have arriv ed in the past five years; since 2005, over a hundred thousand Louisianans perma nently relocated to Texas, mostly in Houston, after Hurricane Katrina. The popul ation is also skewing younger, which means more Democratic. But Munisteri is mor

e preoccupied by the racial and ethnic changes. He turned to a chart showing Tex ass population by ethnic group over the next few decades. A red line, representin g the white population, plunged from almost fifty-five per cent, in 2000, to alm ost twenty-five per cent, in 2040; a blue line, the Hispanic population, climbed from thirty-two per cent to almost sixty per cent during the same period. He po inted to the spot where the two lines crossed, as if it augured a potential apoc alypse. This shows when Hispanics will become the largest group in the state, he s aid. Thats somewhere in 2014. Were almost at 2013! He added, You cannot have a situat ion with the Hispanic community that weve had for forty years with the African-Am erican community, where its a bloc of votes that you almost write off. You cant do that with a group of citizens that are going to compose a majority of this stat e by 2020, and which will be a plurality of this state in about a year and a hal f. He told me that he had a slide that he wouldnt show me, because he didnt want Demo crats to know about his calculations. He said that it depicted the percentage of the white vote that Republicans would have to attract if they continued to do a s poorly as they have among Hispanics. By 2040, youd have to get over a hundred per cent of the Anglo vote, he said. Over a hundred per cent is not possible, I offered. Thats my point! Munisteri travels around the country with his slide show, urgently arguing that Republicans will wither away if they dont adapt. In the spring, he briefed Republ ican members of Texass congressional delegation. After half an hour, a congressma n rose to summarize the material. What youre saying is that if the Republican Party is not doing its job attracting Hispanics to the Party, the Party in a very short time nationally and in Texas w ill be toast? Munisteri replied, Thats it, Congressman. Munisteri has been doing all he can to begin to alter the trajectory of Republic ans in Texas. One of his first projects has been to rebrand the Party. For years , Texas delegates to the Republican National Convention have worn cowboy hats an d loud shirts paid for by the state G.O.P., making them instantly recognizable o n the Convention floor and the subject of a disproportionate number of photograp hs. Its not the image that Munisteri wants to project. This state has a population thats so much more diverse than the rest of the country is aware of, he said. Othe r people think there are cowboys down here and horses and its a bunch of Billy Bo bs. This year, he refused to fund the attire that his delegates regularly wore. I said, Were not buying hats and shirts, because Im tired of having to go to the R.N. C. and have everybody think we dress like that in Texas, he said. But the delegat es rebelled, and some Republican donors decided to buy the outfits for them anyw ay. Munisteri, who as chairman is not supposed to push his own policy ideas on the P arty, has spent a lot of time trying to get Republicans to sound more welcoming to Hispanics. In one sense, he is simply returning to his partys recent past. As governor, George W. Bush was a zealous advocate of reaching out to Hispanics. He supported bilingual education and was in favor of government services, like hea lth care and education, for unauthorized immigrants. As President, he strongly s upported an immigration-reform proposal that would have provided a pathway to ci tizenship for millions of immigrants living in the United States illegally. He s aw it as both business-friendly and as a way for the Party to attract Hispanic s upport and build a more durable coalition than relying disproportionately on whi te voters.

By 2006, the proposal had become anathema to most conservatives, who ridiculed i t as amnesty for illegals. When Bush tried to push it through Congress, conservati ves defeated it, following an often toxic debate that reversed all of Bushs gains among Hispanics. In 2008, McCain, who had sponsored the Bush legislation, lost Hispanics by sixty-seven per cent to thirty-one per cent. In 2012, Romney, who h ad once seemed to support the Bush legislation, moved far to the right on immigr ation, calling on undocumented citizens to self-deport and attacking Governor Perr y for signing legislation, in 2001, that allowed unauthorized immigrants in Texa s to qualify for in-state tuition rates. Munisteri advises Republicans in Texas to talk about Hispanics as an integral pa rt of the states history, whose ancestors, in many cases, arrived in Texas long b efore those of much of the Anglo population. On immigration, he says, the Republ ican base needs reducating, so that conservatives understand that immigration is es sential to the countrys prosperity. In his effort to tug the Texas G.O.P. into the future, Munisteri hired David Zap ata, a young evangelical Christian from a border town, as his Hispanic-outreach director. And he has embarked on a micro-targeting project that uses consumer da ta to find Hispanics who dont vote for Republicans but exhibit buying patterns th at suggest they might be conservative, such as subscribing to Guns & Ammo or giv ing money to pro-life causes. Since 2010, he has succeeded in getting Republican s elected in some of the most Hispanic areas of the state. Munisteris interest in making the Party a home for Hispanics and thus saving his party is partly a result of his own experience. He grew up in the state in the n ineteen-sixties, when it was overwhelmingly white. There was very little diversit y at Anglo high schools, he said. And Im not Anglo. When I was younger, not often, but enough, I was subjected to people who didnt like me just because I was Italia n. You dont ever get to find common ground with other people if they think youre p rejudiced or racist against them. He added, If I overhear you tell a Wop joke . . . I mean, personally, I wont vote for people that I think are prejudiced against Italian-Americans. Even though many Republicans agree that the Party must become more hospitable to Hispanics, there is little consensus on how best to do so and still qualify as conservative. Ted Cruz argues that Hispanics can be won over by appeals to tradi tional values of hard work. Ive never in my life seen a Hispanic panhandler, he sai d, as we rode out of San Antonio. In the Hispanic community, it would be consider ed shameful to be out on the street begging. He added, They have conservative valu es. Hispanics dont want to be on the dole. Theyre not here to be dependent on gove rnment. He rejected the idea that Republicans needed to go back to the Bush-era p olicies on immigration. I think those that say that, for Republicans to connect w ith the Hispanic community, they need to adopt amnesty and not secure the border s, I think thats foolishness. Many Republicans in Texas suggested that the fact that Cruz is Hispanic is enoug h for him to win votes in that community. To prove the point, some mentioned Qui co Canseco, a Republican who won a Texas House seat in 2010 in a Democratic dist rict by running as a Tea Party conservative, and whose relection bid this year wa s closely contested. His district is sixty-six per cent Hispanic and spreads som e six hundred miles, from San Antonio to the western edge of Texas. It includes most of the states border with Mexico. Like Cruz, Canseco, both in 2010 and in 20 12, ran as an opponent of the kind of immigration reforms championed by George W . Bush. A few days before the election, when I interviewed Canseco, who is the s on of Mexican immigrants and was born in Laredo, a border town that is ninety-si x per cent Hispanic, he gave no hint of moderation on any of the immigration iss ues that have become so important to conservative Republicans in the past few ye ars.

Canseco told me that he didnt have any problem with how Romney talked about immig ration, and he said that he opposed the Obama Administrations policy on protectin g some unauthorized immigrants from deportation. Im very much against open borders , because we are a sovereign nation, and Im against amnesty, he said. Instead of r unning on immigration reform, Canseco emphasized social issues. In the final str etch of the campaign, he mailed a bilingual flyer to voters which asserted that Democrats said no to God at their Convention, want to provide abortions for underag e girls, and want marriage to be between man & man. The three accusations were illu strated with a picture of Jesus, one of a baby, and a photograph of two men kiss ing passionately. But to speak of the Hispanic population is an oversimplification, akin to collecti vely describing the waves of immigrants that arrived in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as European-Americans. In Florida, Cuban-Americans tend to vote for Republicans and Puerto Ricans tend to vote for Democrats. In Texas, the Tejanos have deep roots in the state and tend to be more open to the Republican Party; the more recent immigrants from across the border are known simply as Me xican-Americans, who largely came to the United States after the Mexican Revolut ion of 1910, when Mexico established a robust welfare state, and are more common ly Democrats. While Cruz and Canseco embrace a Tea Party approach to the G.O.P.s Hispanic probl em, elsewhere in Texas a different strategy is being tested. One afternoon, I me t with Art Martinez de Vara, the mayor of Von Ormy, a town of thirteen hundred r esidents, southwest of San Antonio, which dates to the eighteenth century. His a ncestors arrived in San Antonio, from colonial Mexico, in the seventeen-nineties . I have family that fought at the Alamo, he said proudly, as we sat in a local ca mpaign office in a strip mall. Martinez de Vara is thirty-seven, with a Chris Ch ristie-size midsection, and he has arguably been more influential within the Par ty than any other immigration reformer of the past few years. In 2008, Martinez de Vara co-founded the Latino National Republican Coalition of Texas, now called the Texas Federation of Hispanic Republicans. A lot of people dont like the word Latino, he said. They find it offensive, or too Californian. The g roup recruits and supports Hispanics to run at the local level in South Texas. I n our conversation, he criticized both Cruzs and Cansecos approaches to their camp aigns. When I asked whether Cruzs Latin surname was enough for him to win over Hi spanics, one of Martinez de Varas friends, Gina Castaeda, a political activist who manages local campaigns, interrupted us. She said, In the Hispanic or Mexican co mmunity, theres some She hesitated. How can I say it nicely? They dont like Cubans. O r Puerto Ricans. Martinez de Vara agreed. Even within Mexico, they look down upon Caribbean Hispanics, he said. But his real problem with Cruz and Canseco was their view on immigration. During Cruzs primary against the states lieutenant governor, David Dewhurst, Martinez de Vara and his group stayed out of the race. We didnt endorse, he said. They both com peted over who was the most extreme on immigration, which we werent that interest ed in. It was about who was the most conservative. He mentioned that among the jo bs on Cruzs long rsum was campaign adviser to Bush. Cruz was part of the Bush team w hen it proposed immigration reform, he said, noting with frustration how Republic ans have flipped on the issue in recent years. He was one of his chief policy adv isers. Martinez de Vara argued that jobs, education, and crime ultimately are more impo rtant issues than immigration to Hispanics in Texas. Still, he insisted that Rep ublicans have to move back to the pro-reform positions of the Bush years. Theres a small faction of the Republican Party that opposes this at every level, he said. What are they proposing? A border wall? Thats massive confiscation of private pro perty. We oppose that in every other context. Its a big-government, big-spending project. We oppose that in every other context. Arming the government with great

er police powers? We oppose that in every other context. This is big-government liberalism, and for conservatives it just makes no sense. In 2010, the platform of the Republican Party of Texas included some of the coun trys most restrictionist language on immigration. It referred repeatedly to illega l aliens and called for an unimpeded deportation process, elimination of all govern ment benefits to unauthorized immigrants, and the adoption of policies that woul d mirror the controversial Show me your papers provision of Arizonas immigration la w. Early this year, Martinez de Vara and his allies from the Texas Federation of Hi spanic Republicans decided that they would rewrite the state Party platform on i mmigration. There was a minority in the Party that was vocal and basically hijack ing that issue, he said. And so we took it to the convention. The Republican Party of Texass convention includes some nine thousand delegates. They met in early Jun e, in Fort Worth. Martinez de Vara pushed new language through a subcommittee on immigration that he chaired and then through a full committee. Munisteri, the P arty chairman, made sure that the issue received a thorough hearing, a move that angered a significant faction of his party. The debate came down to a contentio us floor fight in which the new language was challenged four times. Martinez de Vara rose at one point and delivered the soliloquy that he gave me about how bui lding a wall and confiscating property was big government. When I said that on th e floor of the Republican Party of Texas convention, he said, with nine thousand o f the most diehard conservatives, people who paid two or three thousand dollars to go to Fort Worth and participate, I got seventy-five per cent of the vote. Be cause they all know its true! The platform no longer refers to illegal aliens and no longer has any language tha t could be construed as calling for Arizona-style laws. Instead, it proposes a co mmon ground to find market-based solutions and the application of effective, pract ical and reasonable measures to secure our borders. Rather than expelling eleven million immigrants, it says, Mass deportation of these individuals would neither be equitable nor practical. Most significant, Martinez de Vara won adoption of la nguage calling for a temporary-worker program. At around the time that Mitt Romn ey was winning the primary by attacking his opponents for being too soft on immi gration, the largest state Republican Party in America was ridding its platform of its most restrictionist immigration language and calling for a program to all ow unauthorized immigrants to stay in the U.S. legally and work. A few months later, Martinez de Vara and his group took the fight to the nationa l Convention, in Tampa, where he knew almost nobody. His main antagonist there w as Kris Kobach, Kansass secretary of state and the leader of the movement to spre ad Arizona-style laws. Martinez de Vara wasnt on the national committee, so he bu ttonholed sympathetic members in any way he could. We had to hustle, he said. We we re following people to the bathroom. Although it was little noted at the time, Ma rtinez de Vara and his national allies won the adoption of language saying that Republicans would consider a new guest-worker program. That language sits uneasily beside language about building a double-layered fence, stopping all federal fun ding for benefits for illegals, and dismissing the Justice Departments lawsuit agai nst Arizonas law. You have Kobachs language alongside our language of a national gu est-worker program, Martinez de Vara said. Which is huge. It was a massive shift. We got it in there. The victories have emboldened him. While Cruz and Munisteri and many other Repub licans fret about losing the Hispanic vote, Martinez de Vara sees a future in wh ich he and Hispanic Republicans like him inevitably take over the Party. He alre ady talks about the Anglo population as a minority, one that will have to adapt to whats coming in Texas politics. If youre coming from the Anglo community, you ma y be seeing the death of your party and your political power and the way you und erstand things, he said. You step on our side, the future looks bright. We know th

at we have so much in common with the Anglo community; were not going to alienate it. And in 2040 Texas will be ten per cent African-American, twenty-five per ce nt Anglo, roughly ten per cent Asian, and the rest is going to be Hispanic. We c an build a governing coalition of conservatives among all those people. Its just a different Republican Party than exists today. Back in the headquarters of the Republican Party of Texas, I visited with David Zapata, the state Partys liaison to Hispanics. His parents are from Mexico. (When I asked him the name of their town, he said that he didnt want it published. The cartels, he explained.) Zapata, who is thirty, didnt learn English until high scho ol; he speaks with an accent. His office was decorated with a photograph of Geor ge W. Bush and a Bush-Cheney campaign sign. There was no similarly prominent Rom ney memorabilia. Im a big Bush fan, he told me with a smile. Not for everything elsej ust for the emphasis that he gave to the Hispanic population. The Bush-family legacy looms over the Partys relationship with Hispanics and may yet play a role in shaping it. As governor, George W. Bush won half the Hispanic vote when he was relected, in 1998. In Florida, his brother Jeb, the former gove rnor of that state, who is frequently discussed as a potential Presidential cand idate, was also popular. Look at the Jeb Bush model, which is what we try to foll ow, Munisteri said. Jeb Bush got a higher percentage of the Hispanic vote in Flori da than Marco Rubio, who is of Hispanic descent. Next spring, Jeb is scheduled to publish a book outlining his views on immigration reform. In Texas, Jebs thirtysix-year-old son, George P., whose mother, Columba, grew up in Guanajuato, Mexic o, has recently become a rising voice on the issue of Hispanic outreach. In 2010 , he started the Hispanic Republicans of Texas, a group similar to Martinez de V aras, which recruits, trains, and funds Hispanic Republicans to run for office. B ush works at a private-equity firm that invests in the oil and gas industry, but his allies in the state told me that he would likely run for statewide office i n 2014, and the day after the election he filed the paperwork to do so. Hes got th e talent, and the name, and hes Hispanic, said George P.s friend Juan Hernandez, a Republican consultant who works closely with him. What a combination! A Hispanic Bush! And hes morenohes dark. Bushs policy views are opaque, but he has surrounded hi mself with immigration reformers. For instance, Hernandez has come under attack from conservatives for his liberal views on the issue. On the other hand, Bush e ndorsed Cruz in his contentious primary. He could serve as a bridge between dieh ard conservatives and immigration reformers in the way that his uncle and his fa ther did. Despite the doomsday scenarios outlined by people like Munisteri, the Texas G.O. P. is far ahead of the national Party in dealing with the future. Two strategies are being tested. One is the kind of Republican identity politics exemplified b y Cruz: the Party can continue its ideological shift to the right, especially on immigration, and appeal to Hispanics with candidates who share their ethnicity and perhaps speak their language. The more difficult path would see the G.O.P. r etreat from its current position on immigration and take the direction advocated by Martinez de Vara and the Bush family. If neither of these strategies succeeds, the consequences are clear. California was once a competitive state, the place that launched Ronald Reagan, but the G.O .P. there has now been reduced to a rump party, ideologically extreme and prepon derately white. Republicans hold no statewide offices. After Tuesday, the Democr ats also have a super-majority in the legislature, making it easier to raise tax es and overcome parliamentary obstacles like filibusters. In most accounts, the beginning of the Republican decline in California is traced to former Governor P ete Wilsons attacks on benefits for unauthorized immigrants, which sounded to man y voters like attacks on Hispanics. Farther east, in 2000 and 2004, New Mexico w as one of the closest states in Presidential politics. In 2008, Obama won it by fifteen points. By 2012, it was no longer contested. Similarly, Nevada, which wa s fought over by both candidates this year, and which Obama won by six points, s

eems to have gone the way of California and New Mexico and will likely be safe f or Democrats in 2016. The states arent identical: for example, California is more culturally liberal than Texas. But they all have growing nonwhite populations t hat overwhelmingly reject Republicans. Demography is not necessarily destiny, however. The Democratic Party in Texas is leaderless and disorganized, ill-equipped to capitalize on the Republicans fear of their own extinction. Hispanic turnout is much lower in Texas than in other s tates with large Hispanic populations, such as California, and nobody seems to b e moving aggressively to change the situation. You dont have one person trying to unify the collective energies of the Democratic Party with a goal toward putting a Democrat on the map statewide, said Trey Martinez Fischer, a Democratic state representative who chairs the Mexican American Legislative Caucus. Theres groundwork that needs to be done in Texas that simply hasnt been done, Julin C astro, a Democrat and the mayor of San Antonio, told me during an interview on C NN. He noted that whereas in California Hispanics vote at rates that are ten per cent lower than those of the rest of the electorate, in Texas Hispanics are twe nty-five per cent less likely to vote. But he insisted that change was coming. Wi thin the next six to eight years, he said, I believe Texas will be at least a purp le state, if not a blue state. Last Tuesday, the Democrats showed some signs of life. Zapata had given me a lis t of thirteen Hispanic Republicans I should watch on Election Day in Texas. Elev en of them lost, including Canseco. Cruz won, but his margin in Texas was the sa me as Romneys, suggesting that he had no crossover appeal to Hispanic Democrats. Like the G.O.P.s contradictory language on immigration in its party platform, the two strategies for courting Hispanics co-exist uneasily. The debate in Texas is about to seize Washington. Obama has strongly indicated that he intends to see immigration reformlikely some version of the so-called dream Act, which would off er a path to citizenship for millions of unauthorized immigrantspassed in 2013. B efore the election, Obama told the Des Moines Register that he was confident he co uld get it done, because a big reason I will win a second term is because the Rep ublican nominee and the Republican Party have so alienated the fastest-growing d emographic group in the country, the Latino community. Kay Bailey Hutchinson, the Republican senator from Texas whom Cruz is replacing, told me after the electio n, A compromise on the dream Act should be easy to get done now. If Romney had won, his party would have been able to figure out this vexing issu e from a position of strength. Instead, it will have to respond to the Democrats , who are certain to play the tensions within the G.O.P. One person who understa nds this is Cruz. When we arrived in Austin, at the end of our trip together, he revealed his simple recipe for success. I think every case in litigation and every argument in politics is about the fund amental narrative, he said. If you can frame the narrative, you win. As Sun Tzu sa id, every battle is won before it is fought. And it is won by choosing the field of terrain on which the fight will be engaged. For now, the field belongs to Oba ma and the Democrats, and the storyline on immigration is theirs to lose.

Read more: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2012/11/19/121119fa_fact_lizza#ixz z2C3XM9Cot

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Criminal Complaint Filed Against Tarrant County College District With The District Attorney's OfficeDocument18 pagesCriminal Complaint Filed Against Tarrant County College District With The District Attorney's OfficeIsaiah X. SmithNo ratings yet

- How To Run A Thriving Business - Ralph WarnerDocument374 pagesHow To Run A Thriving Business - Ralph Warnersir bookkeeperNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- We Happy Few by Rolando HinojosaDocument129 pagesWe Happy Few by Rolando HinojosaArte Público PressNo ratings yet

- GPSADocument21 pagesGPSALuisAngelCordovadeSanchezNo ratings yet

- North Texas 2050Document72 pagesNorth Texas 2050Michele AustinNo ratings yet

- HoDocument20 pagesHoShirley Pigott MDNo ratings yet

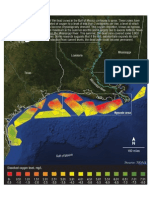

- Dead Zones in The Gulf of MexicoDocument1 pageDead Zones in The Gulf of MexicoSethNo ratings yet

- Statistical Report of State Park Operations: 2011-2012Document58 pagesStatistical Report of State Park Operations: 2011-2012Jake GrovumNo ratings yet

- WCS 15 ProgramDocument40 pagesWCS 15 ProgramColorado Christian UniversityNo ratings yet

- Jolie Daniel) All TX RadiusDocument3 pagesJolie Daniel) All TX RadiusdistrictjNo ratings yet

- Apush 1 Final Exam ReviewDocument13 pagesApush 1 Final Exam ReviewNoah Low-key JawntryNo ratings yet

- City Council Agenda For Jan. 4.Document12 pagesCity Council Agenda For Jan. 4.Erika EsquivelNo ratings yet

- Resume 2Document2 pagesResume 2evanaskieraNo ratings yet

- M Tamez Diss 2010 WsuDocument685 pagesM Tamez Diss 2010 WsuMargo TamezNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Group in The USADocument2 pagesEthnic Group in The USASorgiusNo ratings yet

- Catalyst Nov 192004978 ColoDocument24 pagesCatalyst Nov 192004978 ColoPat McCulloughNo ratings yet

- (Warren Karlenzig, Paul Hawken) How Green Is YourDocument225 pages(Warren Karlenzig, Paul Hawken) How Green Is YourIrdha DiahNo ratings yet

- Election ComplaintDocument61 pagesElection ComplaintJim ParkerNo ratings yet

- 8 Ways To Say "I Love My Life!" Edited by Sylvia Mendoza With A Foreword by Vikki CarrDocument241 pages8 Ways To Say "I Love My Life!" Edited by Sylvia Mendoza With A Foreword by Vikki CarrArte Público PressNo ratings yet

- Texas Revolution Illustrated Timeline AssignmentDocument3 pagesTexas Revolution Illustrated Timeline Assignmentapi-293238977No ratings yet

- Teks Snapshot Social Studies Grade 07 July 2014Document2 pagesTeks Snapshot Social Studies Grade 07 July 2014api-233755289No ratings yet

- Manifest DestinyDocument2 pagesManifest DestinyJake WarnerNo ratings yet

- Electricity Facts Label - Champion Energy - Champ Saver 24Document2 pagesElectricity Facts Label - Champion Energy - Champ Saver 24Electricity RatingsNo ratings yet

- The Route of The Guerra Family in A New CountryDocument4 pagesThe Route of The Guerra Family in A New CountryNgalam NgopiNo ratings yet

- Mcintyre Cindi Generic ResumeDocument2 pagesMcintyre Cindi Generic Resumeapi-267444521No ratings yet

- Gonzales Cannon September 5 IssueDocument26 pagesGonzales Cannon September 5 IssueGonzales CannonNo ratings yet

- Ar 601-94 Police Record CheckDocument9 pagesAr 601-94 Police Record CheckMark CheneyNo ratings yet

- A Self-Guided Tour of The University of Texas at AustinDocument6 pagesA Self-Guided Tour of The University of Texas at AustinFatima CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Gonzales Cannon April 18 IssueDocument28 pagesGonzales Cannon April 18 IssueGonzales CannonNo ratings yet

- Recovering The US Hispanic Literary Heritage, Vol VIII Edited by Clara Lomas and Gabriela Baeza VenturaDocument233 pagesRecovering The US Hispanic Literary Heritage, Vol VIII Edited by Clara Lomas and Gabriela Baeza VenturaArte Público Press100% (1)