Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 1

Uploaded by

Jhing Guzmana-UdangOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 1

Uploaded by

Jhing Guzmana-UdangCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 1: Introduction

Bibliography of Theorist Emile Durkheim was the first French academic sociologist. His life was dominated throughout by his academic career, even though he was intensely and passionately involved in the affairs of French society at large. In his well-established status he differed from the men dealt with so far, and his life may seem uneventful when compared with theirs. Undoubtedly their personal idiosyncrasies had a share in determining their erratic course. But in addition, they were all devoted to a calling that had not yet found recognition in the university. In their attempts to defend the claim to legitimacy of the new science of sociology, they faced enormous obstacles, which contributed in large measure to their personal difficulties. Emile Durkheim, as well as the theorists who will be dealt with in subsequent chapters, faced a different set of circumstances. They were all academic men but were still considered by their colleagues as intruders representing a discipline that had little claim to legitimate status. As a result, theirs was by no means an easy course. Nevertheless, they fought from within the halls of academe rather than from outside, and so their lives tended to be less embattled than those of their predecessors. Emile Durkheim was born at Epinal in the eastern French province of Lorraine on April 15, 1858. Son of a rabbi and descending from a long line of rabbis, he decided quite early that he would follow the family tradition and become a rabbi himself. He studied Hebrew, the Old Testament, and the Talmud, while at the same time following the regular course of instruction in secular schools. Shortly after his traditional Jewish confirmation at the age of thirteen, Durkheim, under the influence of a Catholic woman teacher, had a shortlived mystical experience that led to an interest in Catholicism. But soon afterwards he turned away from all religious involvement, though emphatically not from interest in religious phenomena, and became an agnostic. Durkheim was a brilliant student at the College d'Epinal and was awarded a variety of honors and prizes. His ambitions thus aroused, he transferred to one of the great French high schools, the Lycee Louis-le-Grand in Paris. Here he prepared himself for the arduous admission examinations that would open the doors to the prestigious Ecole Normale Superieure, the traditional training ground for the intellectual elite of France. After two unsuccessful attempts to pass the rigorous entrance examinations, Durkheim was finally admitted in 1879. At theEcole Normale he met with a number of young men who would soon make a major mark on the intellectual life of France. Henri Bergson, who was to become the philosopher of vitalism, and Jean Jaures, the future socialist leader, had entered the year before. The philosophers Rauh and Blondel were admitted two years after Durkheim. Pierre Janet, the psychologist, and Goblot, the philosopher, were in the same class as Durkheim. The Ecole Normale, which had been created by the First Republic, was now having a renaissance and was training some of the leading intellectual and political figures of the Third Republic.

Although admission to the Ecole Normale was an achievement in a young man's life, Durkheim, once admitted, seems not to have been happy at the Ecole. He was an intensely earnest, studious, and dedicated young man, soon nicknamed "the metaphysician" by his peers. Athirst for guiding moral doctrines and earnest scientific instruction, Durkheim was dissatisfied with the literary and esthetic emphasis that still predominated at the school. He rebelled against a course of studies in which the reading of Greek verse and Latin prose seemed more important than acquaintance with the newer philosophical doctrines or the recent findings of the sciences. He felt that the school made far too many concessions to the spirit of dilettantism and tended to reward elegant dabbling and the quest for "novelty" and "originality" of expression rather than solid and systematic learning. Although he acquired some close friends at the school, among whom Jean Jaures was the most outstanding, his earnestness and dedication make him in the eyes of the other students an aloof and remote figure, perhaps even somewhat of a prig. His professors, in their turn, repaid him for his apparent dissatisfaction with much of their teaching by placing him almost at the bottom of the list of successful aggregation candidates when he graduated in 1882. All this does not mean that Durkheim was uninfluenced by his three years at the Ecole Normale. Later on, he spoke almost sentimentally about these years and, if many of his professors irked and annoyed him, there were a few others to whom he was deeply in debt. Among these were the great historian Fustel de Coulanges, author of the Ancient City who became director of the school while Durkheim attended it, and the philosopher Emile Boutroux. He later dedicated his Latin thesis to the memory of Fustel de Coulanges, and his French thesis, The Division of Labor, to Boutroux. What he admired in Fustel de Coulanges and learned from him was the use of critical and rigorous method in historical research. To Boutroux he owed an approach to the philosophy of science that stressed the basic discontinuities between different levels of phenomena and emphasized the novel aspects that emerged as one moved from one level of analysis to another. This approach was later to become a major mark of Durkheim's sociology. Durkheim's Academic Career At about the time of his graduation, Durkheim had settled upon his life's course. His was not to be the traditional philosopher's calling. Philosophy, at least as it was then taught, seemed to him too far removed from the issues of the day, too much devoted to arcane and frivolous hairsplitting. He wanted to devote himself to a discipline that would contribute to the clarification of the great moral questions that agitated the age, as well as to practical guidance of the affairs of contemporary society. More concretely, Durkheim wished to make a contribution to the moral and political consolidation of the Third Republic which, in those days, was still a fragile and embattled political structure. But such moral guidance, Durkheim was convinced, could be provided only my men with a solid scientific training. Hence he decided that he would dedicate himself to the scientific study of society. What he considered imperative was to construct a scientific

sociological system, not as an end in itself, but as a means for the moral direction of society. From this purpose Durkheim never parted. However, since sociology was not a subject of instruction either at the secondary schools or at the university, Durkheim embarked upon a career as a teacher in philosophy. From 1882 to 1887 he taught in a number of provincial Lycees in the neighborhood of Paris--except for one year when he received a leave of absence for further study at Paris and in Germany. Durkheim's stay in Germany was mainly devoted to the study of methods of instruction and research in moral philosophy and the social sciences. He spent most of his time in Berlin and Leipzig. In the latter city the famous Psychological Laboratory of Wilhelm Wundt impressed him deeply. In his subsequent reports on his German experiences, Durkheim was enthusiastic about the precision and scientific objectivity in research that he had witnessed in Wundt's laboratory and elsewhere. At the same time he stressed that France should emulate Germany in making philosophical instruction serve social as well as national goals. He heartily approved of the efforts of various German social scientists and philosophers who stressed the social roots of the notion of moral duty and sought to make ethics an independent and positive discipline. With the publication of his reports on German academic life, Durkheim became recognized at the age of twenty-nine as a promising figure in the social sciences and in social philosophy. In addition to his German studies, he had already published a number of critical articles, including reviews of the work of the German-language sociologists Gumplowicz and Schaeffle, and the French social philosopher Fouille. It was not surprising, therefore, that he was appointed to the staff of the University of Bordeaux in 1887. What was surprising, however, was that at the instigation of Louis Liard, the Director of Higher Education at the Ministry of Public Education, a social science course was created for him at the Faculty of Letters at that university. This was the first time a French university opened its doors to this previously tabooed subject. Only a decade earlier, the furious examiners at the Faculty of Letters of Paris had forced the sociologist Alfred Espinas, a future colleague of Durkheim at Bordeaux, to suppress the introduction to his thesis because he refused to delete the name of Auguste Comte from its pages! At Bordeaux, Durkheim was attached to the department of philosophy where he was charged with courses in both sociology and pedagogy. Some commentators seem to feel that the teaching of pedagogy was a kind of academic drudgery that Durkheim was forced to accept. This was not the case. He continued to teach in the field of education throughout his career, even when he was clearly free to determine for himself the courses he would offer. Education, as will be seen later in more detail, remained for Durkheim a privileged applied field where sociology could make its most important contribution to that regeneration of society for which he aimed so passionately. At about the time of his academic appointment to Bordeaux, Durkheim married the former Louise Dreyfus. They had two children, Marie and Andre, but very little is known of his family life. His wife seems to have devoted herself fully to his work. She followed the traditional Jewish family pattern of taking care of family affairs as well as assisting

him in proofreading, secretarial duties, and the like. Thus, the scholar-husband could devote all his energies to his scholarly pursuits. The Bordeaux years were a period of intense productive activity for Durkheim. He continued to publish a number of major critical reviews, among others of Toennies' Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, and the opening lectures of some of his courses were published in the form of articles. In 1893, he defended his French doctoral thesis, The Division of Labor, and his Latin thesis on Montesquieu. Only two years later The Rules of Sociological Method appeared, and within another two years Le Suicide was published. With these three major works, Durkheim moved into the forefront of the academic world. He noted in the preface of Suicide that sociology was now "in fashion." Not that his work was universally praised; on the contrary, it created a number of famous controversies and polemical exchanges. But the fact that so many theorists were moved to regard Durkheim as their privileged adversary testifies to his impact on the intellectual world. Then, as later, Durkheim was the center of continued controversy and disputation. Once having established sociology as a field of interest to a wider public, Durkheim soon felt the need to consolidate these gains by setting up a scholarly journal entirely devoted to the new discipline. L'Annee Sociologique, which he founded in 1898, soon became the center for an extraordinarily gifted group of young scholars, all united, despite a variety of specific disciplinary interests, in a common devotion to the Durkheimian approach to sociology. Each year the Annee analyzed the current literature of sociology in France and elsewhere. These critical accounts allowed the French public for the first time to gain an overall view of the depth and breadth of the sociological enterprise. The Annee also contained independent major contributions from the pen of Durkheim and from his close collaborators. The reviews and papers were all meant to emphasize the need for building conceptual bridges between the specialized fields of the social sciences and the correlative need for factual, specific, and methodical research. The Annee was successful from the beginning, and the continued collaboration of its key contributors helped to weld them together into a cohesive "school," aggressively eager to defend the Durkheimian approach to sociology against all who opposed it. In the same year the Annee was born, Durkheim published his famous paper on Individual and Collective Representations, which served as a kind of manifesto of sociological independence for the Durkheimian school. A series of other seminal papers, some published in the Annee and some elsewhere, followed in the next decade and a half. These included "The Determination of Moral Facts," "Value Judgments and Judgments of Reality," "Primitive Classification" (with Marcel Mauss), and "The Definition of Religious Phenomena." Nine years after having joined the faculty of the University of Bordeaux, Durkheim was promoted to a full professorship in social science, the first such position in France. He occupied this chair for six years. In 1902, now a man fully recognized stature, he was called to the Sorbonne, first as a charge de cours and then, in 1906, as a Professor of the Science of Education. In 1913, the name of Durkheim's chair was changed by a special ministerial decree to "Science of Education and Sociology." After more than

three quarters of a century, Comte's brainchild had finally gained entry at the University of Paris. During his Paris years, Durkheim continued to edit the Annee and offered a wide range of courses in ethics, education, religion, the philosophy of pragmatism, and the teachings of Saint-Simon and Comte. He appears to have been a masterful lecturer who held his audience so much in thrall that one of his students could write, "Those who wished to escape his influence had to flee from his courses; on those who attended he imposed, willy-nilly, his mastery." During the last few years of his stay in Bordeaux, Durkheim had already become interested in the study of religious phenomena. At least in part under the influence of Robertson Smith and the British school of anthropology, he now turned to the detailed study of primitive religion. He had published a number of preliminary papers in the area, and this course of studies finally led to the publication in 1912 of Durkheim's last major work, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. His scholarly work in the Paris period, though extensive, by no means exhausted Durkheim's energies. He played a major role in the general intellectual life of France, as well as in the university. He was an active defender of Dreyfus during the heyday of the affair and attained eminence as a left-of-center publicist and spokesman. Durkheim also became a key figure in the reorganization of the university system. He served on innumerable university committees, advised the Ministry of Education, helped to introduce sociology into school curricula, and in general did yeoman's work to make sociology the cornerstone of civic education. In these years he came nearest to realizing his youthful ambition of building a scientific sociology that would be applied to moral re-education in the Third Republic and at the same time to the development of a secular morality. When the war came, Durkheim felt obliged to aid his beleaguered fatherland. He became the secretary of the Committee for the Publication of Studies and Documents on the War, and published several pamphlets in which he attacked pan-Germanism and more particularly the nationalistic writings of Treitschke. Just before Christmas, 1915, Durkheim was notified that his son Andre had died in a Bulgarian hospital from his war wounds. Andre had followed his father to the Ecole Normale and had begun a most promising career as a sociological linguist. He had been the pride and hope of a father who had seen him as his destined successor in the front rank of the social sciences. His death was a blow from which Durkheim did not recover. He still managed to write down the first paragraphs of a treatise on ethics on which he had one preparatory work for a long time, but his energy was spent. He died on November 15, 1917, at the age of fifty-nine. Emile Durkheim, the agnostic son of devoted Jews, had managed during his career to combine scientific detachment with intense moral involvement. He was passionately devoted to the disinterested quest for truth and knowledge, and yet he was also a figure not unlike the Old Testament prophets, who castigated their fellows for the errors of their ways and exhorted them to come together in a common service to moral unity and communal justice. Although a Frenchman first and foremost, he did not waver from his

allegiance to a cosmopolitan liberal civilization in which the pursuit of science was meant to serve the enlightenment and guidance of the whole of humanity. A man made of whole cloth, he still managed to play a variety of roles in a distinctive intellectual and historical context.

You might also like

- Appointment Reminder PassportDocument4 pagesAppointment Reminder PassportJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- CertDocument1 pageCertJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

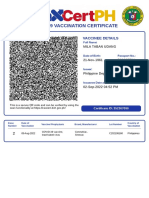

- VaxcertDocument1 pageVaxcertJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- M1-RM-O3-CAD-03 Reference Manual December 28, 2015 0: Section: Process Goals Subject: Contracts ReviewDocument1 pageM1-RM-O3-CAD-03 Reference Manual December 28, 2015 0: Section: Process Goals Subject: Contracts ReviewJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Vax CertDocument1 pageVax CertJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Map of the Twelve TribesDocument6 pagesMap of the Twelve TribesJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Udang, Mila T.Document1 pageUdang, Mila T.Jhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Vax CertDocument1 pageVax CertJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Vaccination Certificate: Vaccinee DetailsDocument1 pageCovid-19 Vaccination Certificate: Vaccinee DetailsJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- VaxcertDocument1 pageVaxcertJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- M1-RM-O3-CAD-03 Reference Manual December 28, 2015 0: Section: Process Goals Subject: Legal Documentation and RemediesDocument1 pageM1-RM-O3-CAD-03 Reference Manual December 28, 2015 0: Section: Process Goals Subject: Legal Documentation and RemediesJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- VaxcertDocument1 pageVaxcertJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Official Receipt PDFDocument1 pageOfficial Receipt PDFJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- January To March PLO ReportDocument2 pagesJanuary To March PLO ReportJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- What Price Are You Willing To PayDocument2 pagesWhat Price Are You Willing To PayJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- PoemDocument1 pagePoemJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Youth Spiritual Gifts TestDocument25 pagesYouth Spiritual Gifts TestMark GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Personal LettersDocument1 pagePersonal LettersJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- HistoryDocument16 pagesHistoryKamran KhanNo ratings yet

- Tax Quick Reviewer - Edward Arriba PDFDocument70 pagesTax Quick Reviewer - Edward Arriba PDFDanpatz GarciaNo ratings yet

- Success Fee DefinitionDocument9 pagesSuccess Fee DefinitionJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Tax Quick Reviewer - Edward Arriba PDFDocument70 pagesTax Quick Reviewer - Edward Arriba PDFDanpatz GarciaNo ratings yet

- Title Layout: SubtitleDocument11 pagesTitle Layout: SubtitleJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Income Tax Reviewer Edward ArribaDocument26 pagesIncome Tax Reviewer Edward ArribaOdarbil BasogNo ratings yet

- Business Project Plan TemplateDocument14 pagesBusiness Project Plan TemplateDitome Madai WakeyNo ratings yet

- Attendance SheetDocument3 pagesAttendance SheetJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Torts and Damages - Aquino Reviewer - With Quasi Contract - Edward ArribaDocument13 pagesTorts and Damages - Aquino Reviewer - With Quasi Contract - Edward Arribahaima macarambonNo ratings yet

- Title Layout: SubtitleDocument11 pagesTitle Layout: SubtitleJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- JurisprudenceDocument51 pagesJurisprudenceJhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- Taxation Cases Batch 4Document21 pagesTaxation Cases Batch 4Jhing Guzmana-UdangNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Reynolds PPT Ch01 An Overview of EthicsDocument29 pagesReynolds PPT Ch01 An Overview of EthicsLi Yu80% (5)

- Shs Daily Lesson Log in Practical Research 2Document36 pagesShs Daily Lesson Log in Practical Research 2Pepito Manloloko96% (25)

- Biodiversity Has Emerge As A Scientific Topic With A High Degree of Social Prominence and Consequently of Political ImportantDocument5 pagesBiodiversity Has Emerge As A Scientific Topic With A High Degree of Social Prominence and Consequently of Political ImportantFatin SakuraNo ratings yet

- Reading Comprehension Exercise # 211Document2 pagesReading Comprehension Exercise # 211Nuria CabreraNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric HX Taking and MSEDocument45 pagesPsychiatric HX Taking and MSERhomizal Mazali100% (2)

- Kanarev Photon Final PDFDocument12 pagesKanarev Photon Final PDFMaiman LatoNo ratings yet

- ERP Implementation and Upgrade in KenyaDocument288 pagesERP Implementation and Upgrade in Kenyasanyal2323No ratings yet

- Revisied Final Ecs 2040 ManualDocument113 pagesRevisied Final Ecs 2040 Manualapi-346209737No ratings yet

- Guido Adler: 1.2 A Pioneer of MusicologyDocument3 pagesGuido Adler: 1.2 A Pioneer of MusicologyAnonymous J5vpGuNo ratings yet

- Persian 3 Minute Kobo AudiobookDocument194 pagesPersian 3 Minute Kobo AudiobookslojnotakNo ratings yet

- Translations of Persian LiteratureDocument18 pagesTranslations of Persian LiteratureAfshin IraniNo ratings yet

- Richard Brodie - Virus of The MindDocument8 pagesRichard Brodie - Virus of The MindtempullyboneNo ratings yet

- 03004-03006-03007 S1-Complex Analysis and Numerical Methods-QPDocument3 pages03004-03006-03007 S1-Complex Analysis and Numerical Methods-QPARAV PRAJAPATINo ratings yet

- Growing Up Hindu and Muslim: How Early Does It Happen?: Latika GuptaDocument7 pagesGrowing Up Hindu and Muslim: How Early Does It Happen?: Latika Guptagupta_latikaNo ratings yet

- Tudor Pirvu One Page CVDocument1 pageTudor Pirvu One Page CVTudor Ovidiu PirvuNo ratings yet

- Time management tips for businessDocument4 pagesTime management tips for businessAnia Górska100% (1)

- Grade 8 Module Physical Education 3rd Quarter PDFDocument64 pagesGrade 8 Module Physical Education 3rd Quarter PDFAiza Rhea Perito Santos100% (3)

- Retire Statistical Significance NatureDocument3 pagesRetire Statistical Significance NaturebNo ratings yet

- Origins of South African LawDocument43 pagesOrigins of South African LawValentineSithole80% (5)

- 4-Tupas v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pages4-Tupas v. Court of AppealsFelicity HuffmanNo ratings yet

- Propositional Logic and Set Theory Sample ExamDocument3 pagesPropositional Logic and Set Theory Sample Examzerihun MekoyaNo ratings yet

- Subject: Social Studies Grade: 8 Topic: Understanding Worldview MaterialsDocument10 pagesSubject: Social Studies Grade: 8 Topic: Understanding Worldview Materialsapi-390372317No ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Case Digest on Prohibitions for Government LawyersDocument6 pagesLegal Ethics Case Digest on Prohibitions for Government LawyersMel Loise Delmoro100% (1)

- EVE Online Chronicles PDFDocument1,644 pagesEVE Online Chronicles PDFRazvan Emanuel GheorgheNo ratings yet

- Taghoot ExplainedDocument10 pagesTaghoot ExplainedTafsir Ibn KathirNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Types of FeminismDocument25 pagesChapter 3 Types of FeminismHajra QayumNo ratings yet

- Ziad BaroudiDocument12 pagesZiad BaroudiusamaknightNo ratings yet

- Telephone Etiquette: Identify YourselfDocument3 pagesTelephone Etiquette: Identify YourselfGisela AlvesNo ratings yet

- Ulrich 1984Document12 pagesUlrich 1984Revah IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Effect Of Advertisement On Honda Two-Wheeler SalesDocument8 pagesEffect Of Advertisement On Honda Two-Wheeler SalesHitesh KakadiyaNo ratings yet