Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Feenstra Econ IR Chap8

Uploaded by

thtf8493Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Feenstra Econ IR Chap8

Uploaded by

thtf8493Copyright:

Available Formats

15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

Notes to Instructor

Chapter Summary Chapter 15 examines the choice of xed versus oating exchange rate regimes in more detail. We consider the potential benets of a xed exchange rate regime, such as efciency gains from reduced transactions costs, scal discipline, and reducing valuation effects, and the costs, such as loss of stabilization policy. We study exchange rate systems that involve cooperative and noncooperative adjustments. The chapter concludes with an overview of two key exchange rate systems: the gold standard and the Bretton Woods system. Comments The majority of this chapter is dedicated to weighing the costs and benets of xing the exchange rate. Fixed versus oating exchange rate regimes were briey examined in the previous chapter. Here we devote more attention to the trade-offs facing a country when it chooses an exchange rate regime. This is a useful precursor to the theory of optimum currency area, which is presented in more detail in Chapter 20. The chapter concludes with a historical overview of exchange rate systems from the gold standard to the present.

317

318 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

Lecture Notes

This chapter considers the costs and benets associated with maintaining an exchange rate peg. As described by the historical overview of the international monetary experience at the end of this chapter, the choice to x versus oat is not straightforward. In addition to using the IS-LM-FX model from the previous chapter, this chapter introduces a new model to examine these trade-offs: the symmetry-integration diagram. This allows us to better understand the benets and costs of xing and to examine a variety of xed exchange rate systems.

1 Exchange Rate Regime Choice: Key Issues

Historically, xed exchange rates were the preferred exchange rate regime among economists and policy makers. Most countries adopted the gold standard, a system in which the value of a countrys currency was pegged to an ounce of gold. Because most countries adopted the gold standard, their currencies were xed relative to each other. Figure 15-1 shows a timeline of exchange rate regimes. The years 19141917 and 19401944 were World Wars and, as such, are omitted from the textbook gure and this discussion. 18701913: Metallic standards, especially the gold standard (peak: 70% of countries in 1913) 19181939: Gold standard returned, then declined during the Great Depression 19451970s: Fixed exchange rate regimes common (Bretton Woods), with most currencies pegged to the U. S. dollar and British pound 1970spresent: Floating exchange rate regimes more common, especially among the worlds wealthiest countries

APPLICATION

Britain and Europe: The Big Issues

This application examines Great Britains 1992 decision to move from a xed to a oating exchange rate regime, highlighting key issues in the exchange rate regime debate. As countries in the European Union (EU) moved toward a single currency unit in the 1980s and 1990s, they adopted exchange rate pegs relative to each other, called the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). It was believed the adoption of a common currency in Europe would promote trade by lowering transactions costs. In addition, from Britains perspective, the ERM would help anchor ination to Germanys low ination rate. It joined the ERM in 1990. In practice, ERM members were pegged to the German deutschmark (DM) because the Bundesbank had monetary autonomy and pursued antiinationary policies. The DM served as the base currency or center currency. In the analysis, we treat Britain as the home country and Germany as the foreign country. As countries in Eastern Europe moved away from communism, the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, reunifying East Germany and West Germany. East Germany lagged behind West Germany and required signicant public spending for social programs and to modernize infrastructure.

A Shock in Germany

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

319

This scal expansion led to an increase in output, creating inationary pressure and an increase in Germanys interest rate. The Bundesbank responded by cutting the money supply to stabilize output, further raising Germanys interest rate. This is illustrated in Figure 15-2, panel (a).

Choices for the Other ERM Countries An increase in Germanys interest rate had two effects on ERM countries, illustrated in panels (b) and (c) of Figure 15-2. IS curve shifts to the right. Higher German interest rates leads to expenditure switching in favor of home-country goods, so the trade balance rises, increasing external demand in the home country. This happens in both a oating and a xed exchange rate regime. LM curve shifts to the left. To prevent depreciation against the DM, interest rates must be increased elsewhere in the ERM. Central banks must follow Germanys lead, cutting the money supply and raising the nominal interest rate to keep the exchange rate xed. Choice 1: Float and Prosper Option 1: Britain chooses to keep its inter-

est rate unchanged (Point 4) IS curve shifts to the right. LM curve shifts to the right. To keep the interest rate unchanged, the Bank of England would need to expand the money supply, shifting LM to the right. To keep the home interest rate unchanged, the new equilibrium is at point 4, where output increases and the pound depreciates relative to the DM.

Choice 2: Peg and Suffer Option 2: Britain remains part of the ERM (Point 2) IS curve shifts to the right. LM curve shifts to the left. To remain part of the ERM, Britain would reach a new equilibrium at point 2, suffering a decrease in output, while the exchange rate is unchanged. Option 3: Britain stabilizes output (Point 3) IS curve shifts to the right. LM curve shifts to the left (by a smaller amount than is required to maintain peg). Bank of England contracts the money supply only by the amount needed to stabilize output. To stabilize output, Britain reaches a new equilibrium at point 3, at which the pound depreciates relative to the DM. What Happened Next? Britain opted out of the ERM, not wanting German-specic events to dictate domestic policy. Figure 15-3 compares Britain with France, a country that opted to remain part of the ERM. The British economy boomed (Point 4), whereas France suffered a recession (Point 2). The benets of integration into the Eurozone are longer term, so it is difcult to determine whether the costs outweighed the benets for Britain.

320 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

Key Factors in Exchange Rate Regime Choice: Integration and Similarity Measuring the costs and benets of a xed exchange rate regime usually means examining the degree of economic integration and economic similarity. Economic integration is measured by the volume of trade among the countries as well as the amount of other cross-border transactions. Economic similarity means that the countries experience similar shocks at similar times. Each country will face a different set of costs and benets. Like Britain and France, they will reach different conclusions about whether to x or oat. Economic Integration and the Gains in Efciency Economic integration refers to the growth of market linkages in goods, capital, and labor markets between countries. Lowering transactions costs through a xed exchange rate will help promote economic integration. Because exchange rate uctuations create uncertainty about prices, they create a barrier to cross-border exchange of goods, capital, and labor. The more countries engage in these transactions, the higher the costs of exchange rate uctuations. A greater degree of economic integration between the home and base countries means a larger volume of transactions. This implies greater benets from xed exchange rate regimes and increased efciency benets from adopting a common currency. Economic Similarity and the Costs of Asymmetric Shocks An asymmetric shock is a shock that affects one country, leaving others unaffected. This was the case of the shock created by German reunication. Asymmetric shocks create conicts in policy objectives of the countries with xed exchange rates. In contrast, symmetric shocks are those that are common to all countries that are part of the xed exchange rate regime. If countries experience the same shock, they will have the same policy response to stabilize output, leaving the exchange rate unchanged. A greater degree of economic similarity between the home and base countries means the countries face more symmetric shocks and fewer asymmetric shocks. That implies lower costs from the xed exchange rate regime and decreased stability costs of a common currency Simple Criteria for a Fixed Exchange Rate Now that we have identied the efciency benets and stability costs, we can dene a net benet of xed versus oat. Two conclusions emerge from the previous discussion: As integration rises, the efciency benets of a common currency increase. As symmetry rises, the stability costs of a common currency decrease. Figure 15-4 illustrates the symmetry-integration diagram, showing these trade-offs in terms of symmetry of shocks (lower stability costs) and market integration (higher efciency gains). The examples given on the graph are based on a geographic sense of economic integration and market integration. Instructors may nd it useful to discuss this from the perspective of a campus location in the city, state or province, country, or region among a group of countries nearby.

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

321

On the diagram, the FIX line indicates where the net benet of a xed exchange rate regime is equal to zero. Above the FIX line high degree of economic integration, symmetric shocks net benet 0 xed exchange rate regime Below the FIX line low degree of economic integration, asymmetric shocks net benet 0 oating exchange rate regime The following two applications consider empirical evidence about whether xed exchange rate regimes in fact promote efciency gains and hinder output stability.

APPLICATION

Do Fixed Exchange Rates Promote Trade?

A xed exchange rate regime eliminates exchange rate volatility, reducing the transactions costs associated with cross-border exchange. Specically, under a pure xed exchange rate, there is no exchange rate risk. Our hypothesis is that removing this risk will increase the volume of trade. Economic historians found that pairs of countries that adopted the gold standard in the late 19th and early 20th centuries enjoyed trade levels 30% to 100% higher than those with oating exchange rates. Today, there are several versions of a xed exchange rate regime, making this a challenging question to answer empirically. We can classify countries in four ways: Common currency (A and B use the same currency unit) Direct exchange rate peg (As currency is xed to Bs) Indirect exchange rate peg (A and B have an exchange rate peg with a third country, C) Floating exchange rate regime (A and Bs currencies are not linked directly or indirectly) Figure 15-5 tells the story. Countries with a common currency have a 38% higher trade volume than a oating rate. Countries that directly peg their exchange rates to each other have a 21% higher trade volume. There is no signicant benet for countries with indirect pegs

Benets Measured by Price Convergence Benets Measured by Trade Levels

If xed exchange rates lower transactions costs, differences in prices should be smaller among countries with xed exchange rates. Earlier, we examined how nominal exchange rates are linked through relative prices, using the law of one price (LOOP) and purchasing power parity (PPP). LOOP and PPP are more likely to hold in a xed exchange rate regime if the argument posited previously is true. Research on prices of baskets of goods shows that as exchange rate volatility rises, price differences widen, and the speed of convergence in the prices (toward PPP) decreases. For individual goods, as exchange rate volatility rises, there are larger price differences across locations. In the case of Europe, the price gaps have narrowed among ERM/euro countries and widened for those countries that left the ERM.

322 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

APPLICATION

Do Fixed Exchange Rates Diminish Monetary Autonomy and Stability?

If capital markets are unrestricted, then uncovered interest parity (UIP) holds, and the home interest rate must be equal to the foreign interest rate. Therefore, policy in the base country dictates economic conditions in the countries pegged to the base currency. This application examines to what extent xed exchange rate regimes imply interest rate parity (e. g. , no monetary policy autonomy) and affect output stability.

The Trilemma, Policy Constraints, and Interest Rate Correlations Solutions to the trilemma: 1. Open capital markets with xed exchange rate (open peg) 2. Open capital markets with a oating exchange rate (open nonpeg) 3. Closed capital markets (closed) Note that case 1 implies that monetary policy is not autonomous, so interest rates in the home country move one-for-one with the base country. Cases 2 and 3 imply autonomous monetary policy, so that changes in interest rates across countries are independent. Figure 15-6 shows interest rate movements in home countries relative to a base country. The estimated slope of the line should be equal to 1 in case 1. The data support this observation: 1. Panel (a): slope 0. 88 (close to 1) 2. Panel (b): slope 0. 58 3. Panel (c): slope 0. 39 Costs Measured by Output Volatility Loss of monetary policy autonomy may not be a bad thing if central bankers are irresponsible or unable to achieve macroeconomic objectives. In some sense, the costs of a xed exchange rate regime hinge more on output stability than monetary policy autonomy. As shown in Figure 15-7, output volatility is higher for countries with a xed exchange rate regime relative to oat. The data show the instability is higher for poorer countries. This suggests that loss of monetary policy autonomy is costly in terms of output stability. From the gure, countries using intermediate exchange rate regimes experience roughly the same volatility as oat.

2 Other Benets of Fixing

This section extends the discussion of costs and benets of xed exchange rate regimes beyond economic integration and output stability. Fiscal Discipline, Seigniorage, and Ination A xed exchange rate regime prevents the government from nancing a budget decit by printing money. Since monetary policy must be dedicated to maintaining the exchange rate, the central bank cannot simply create money for the government to spend. In a oating exchange rate regime, the government may opt to monetize a decit by printing money. This expansion of the

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

323

money supply inevitably leads to high ination and imposes an ination tax (seigniorage) on the public. In this way, the xed exchange rate regime can, in theory, serve as a nominal anchor. Table 15-1 shows that xed exchange rate regimes do not prevent ination. However, when we examine subgroups, we observe that the adoption of a xed exchange rate regime does eventually reduce ination in emerging markets and developing countries. In general, xed exchange rate regimes are neither necessary nor sufcient to ensure low ination. Developing countries suffering from high ination rates are an exception, as exchange rates may serve as the only viable nominal anchor for these countries.

S I D E

The Ination Tax

B A R

The extra money printed to purchase goods and services is worth M / P ( M / M) (M / P) (M / P). In the example above, the $1 tax borne by the public is paid to the government. We can see how this relates to the interest rate by using the money market equilibrium condition: Seigniorage (M / P) L(r* )Y

This section considers why monetizing the decit imposes an ination tax (seigniorage) on the public. Assume output is xed, prices are exible, and ination and the nominal interest rate are constant. In this case, the growth rate of the money supply is equal to the ination rate, M / M . From the Fisher effect, we know i r* . The ination created from monetizing the decit erodes the purchasing power of money. When the public holds money balances M / P, as prices rise, the value of real money balances outstanding falls. For example, if you hold $100 and P 1, when the government expands M by 1%, P grows by 1%, so your real money balances fall to $99 ($100 / 1.01). Therefore, this acts as an ination tax, transferring resources from the public to the government.

Note that the revenue generated by monetizing the decit is offset partially by a decrease in real money demand. In the extreme case of a hyperination, money demand collapses to zero, eliminating potential seigniorage for the government.

Liability Dollarization, National Wealth, and Contractionary Depreciations Many developing countries and emerging markets suffer from liability dollarization, in which a large portion of foreign investment from abroad is denominated in another currency. This creates the potential for large destabilizing wealth effects when the exchange rate changes. Assumptions: Two countries, home (pesos) and foreign ($). Nominal exchange rate, Epesos/$ Home external assets AH denominated in home currency (pesos) AF denominated in foreign currency ($) EAF measured in home currency (pesos) Home external liabilities LH denominated in home currency (pesos) LF denominated in foreign currency ($) ELF measured in home currency (pesos)

324 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

Home countrys total external wealth is the sum of total assets less the liabilities expressed in home currency:

W (AH EAF) (LH ELF)

Suppose the exchange rate changes by E. The change in wealth is (valuation effect):

W E (AF LF)

From the expression, there are two possible cases following a depreciation, E 0: If AF LF, then external wealth increases If AF LF, then external wealth decreases (liability dollarization)

Destabilizing Wealth Shocks Note that wealth effects may offset or magnify the effects of a depreciation on aggregate demand. Although a depreciation increases the trade balance, it also affects wealth because: Consumption may be a function of wealth if households save or borrow. Investment may be a function of wealth if the ability of rms to obtain credit depends on their net worth. When a countrys foreign currency assets do not equal foreign currency liabilities, it has a currency mismatch on its external balance sheet. Now consider how stabilization policy (a monetary expansion) affects the economy differently in the presence of wealth effects. If AF LF, then external wealth increases C and I increase policy effect on output magnied If AF LF, then external wealth decreases C and I decrease policy effect on output dampened In theory, a currency depreciation could actually be contractionary if the valuation effects are large enough! And this is important for developing countries, whose external liabilities are often nearly completely dollarized. Evidence Based on Changes in Wealth

Figure 15-8 reports data on the cumulative change in external wealth associated with valuation effects during currency crises from 1993 to 2003. From the gure, these valuation effects can be quite large, although they depend on the percent depreciation in the currency. Countries with a larger fraction of liabilities denominated in another currency (dollars or yen in these cases) or those experiencing larger depreciations suffered larger losses in wealth.

Evidence Based on Output Contractions Do these wealth effects matter for output? Figure 15-9 plots the relationship between the percentage change in output against the wealth losses associated with valuation effects. The gure shows a clear relationship: countries suffering larger wealth losses experienced more severe contractions in output. Original Sin Historically, most countriesespecially those less-developed countries operating on the fringes of the global capital marketwere forced to borrow in gold or in a hard currency, such as the British pound or the U. S. dollar. This created a currency mismatch. Table 15-2 reports data on the percentage of external liabilities denominated in foreign currency across groups of countries. Wealthier countries have a relatively small percentage of

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

325

their external liabilities denominated in foreign currency. But the rest of the countries have between 72% and 100% of external debt denominated in foreign currency. Original sin refers to a countrys inability to borrow in its own currency. This problem arises partly from a countrys historical macroeconomic policies. As the value of domestic currency debts was eroded by ination, creditors required the debts be denominated in a foreign hard currency.

Options for Redemption?

Another perspective argues that the real source of the problem is golbal capital market failure. Because small countries have a small pool of liabilities traded, investors benet little from diversication into these liabilities. These liabilities are more appealing when they are bundled with others in the form of a security denominated in a single currency. Another prescription involves improving institutional quality and designing better macroeconomic policy to achieve low ination. Finally, countries can reduce currency mismatch through the central banks acquisition of foreign currency and sovereign wealth funds (increasing AF).

Practical Limitations

Government borrowing denominated in foreign currency is still a problem. Also, currency mismatch in private sectors is a problem, compounded by moral hazard (excessive risk-taking with the expectation of a government bailout). The private sector is unable to hedge against exchange rate risk because their capital markets are underdeveloped. What does this mean for the xed versus oating debate? Among countries that cannot borrow in their own currency, oating exchange rates are less useful as a stabilization tool and may be destabilizing. This is particularly true of developing countries, so these countries will prefer xed to oating exchange rates, all else equal. Summary In addition to economic integration and economic similarity, there are several factors that inuence a countrys decision to adopt a xed exchange rate regime: Fixed exchange rates impose scal discipline by preventing the imposition of an ination tax (seigniorage) on the public. Fixed exchange rates avoid large changes in external wealth among countries with assets and liabilities denominated in a foreign currency. These factors are more compelling for poorer countries, leading to a fear of oating. These additional considerations inuence the symmetry-integration diagram as illustrated in Figure 15-10. The benets of scal discipline and avoidance of wealth effects shift the FIX line down because they add to the net benet a country receives from adopting a xed exchange rate regime.

326 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

3 Fixed Exchange Rate Systems

In reality, there are several types of xed exchange rate systems, often involving multiple countries, such as the Bretton Woods system and the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). These are examples of reserve currency systems in which N countries participate. The center (or base) country, usually assigned the number N, is the currency to which all other countries peg. And the base country supplies the reserve currency for the rest of the world. At the beginning of this chapter, we studied Britains decision to leave the ERM and allow the pound to oat (Application: Britain and Europe: The Big Issues). At that time, the German Deutschmark (DM) was the base currency. Germany, as the center country, had monetary policy autonomy. The German central bank had the luxury of choosing i*. ERM countries had to set their interest rates equal to i* to maintain the peg. This fundamental asymmetry is known as the Nth currency problem. An alternative to the approach studied earlier is for countries to reach cooperative arrangements. There are two kinds of agreements studied in this chapter: Mutual agreement and compromise between the center and noncenter countries through the adjustment of interest rates. Mutual agreement to change the exchange rate peg. Cooperative and Noncooperative Adjustments to Interest Rates In the following examples, the home country is the noncenter country and the foreign country is the center country. Suppose the noncenter country experiences an adverse demand shock but the center country does not. This is shown as a leftward shift in the home countrys IS curve in Figure 15-11. Noncooperative (Point 1) To maintain the exchange rate peg, the home country must reduce the money supply, shifting LM to the left to keep the interest rate unchanged. With no response from the center country, each countrys equilibrium is at Point 1. The noncenter countrys Y is below the desired level, whereas the center countrys Y* is equal to the desired level. Cooperative (Point 2) The center country agrees to allow its output to expand, lowering interest rates by shifting the LM* curve to the right. The noncenter country follows, shifting the LM curve to the right, reducing the loss in output. Because the home countrys interest rate falls, the IS* curve shifts to the left (all else equal, the center countrys trade balance improves when the noncenter countrys interest rate falls). Similarly, IS shifts left because i* falls. Point 2 is the cooperative equilibrium, with the center country experiencing a small increase in Y* and the noncenter country experiencing a small decrease in Y.

Caveats

Cooperative arrangements may arise if the countries seek to limit exchange rate volatility without a hard peg. In this way, the countries can achieve most of the benets of xing without high stability costs.

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

327

In practice, these cooperative arrangements are rarely credible. The shocks that hit a group of countries are often asymmetric, and it may be difcult for one country to allow output to deviate from the desired level to help out another country. In the end, these asymmetric shocks should average out, but this requires a long-term commitment. For example, in the ERM, countries pleaded with Germany to ease its monetary policy, which would to reduce the contraction in output felt elsewhere in Europe. As demonstrated in the case of the ERM and Germany, the center country has a great deal of autonomy and may be unwilling to give it up, making cooperative agreements difcult to achieve. Cooperative and Noncooperative Adjustments to Exchange Rates Instead of adjusting interest rates, suppose that countries agree to reset their exchange rate pegs following a shock. Countries that previously had an exchange rate peg at E1 announce that the new peg is E2 E1. E E1: devaluation (in the home currency) 2 E E1: revaluation (in the home currency) 2 In the following examples, both the home and foreign countries are the noncenter. Devaluation and revaluation are analogous to depreciation and appreciation, except these terms are used only to describe changes in exchange rate pegs. Figure 15-2 shows the effects of a home-country devaluation relative to the other countries. The devaluation is achieved through a monetary expansion (LM shifts right), leading to a devaluation in the home currency that boosts the trade balance and increases demand (IS shifts right) such that interest rates are unchanged. Cooperative (Point 2) The devaluation in the home country leads to a decrease in demand in the foreign noncenter country. The foreign noncenter countrys IS* curve shifts to the left. The foreign central bank shifts LM* to the left to maintain interest rate parity (this is a one-time change in the exchange rate). The foreign country agrees to let output Y* fall to bring the home country closer to the desired output. Noncooperative (Point 3) Here, the home country implements a larger devaluation, causing a large increase in the demand for home goods and a large decrease in the demand for foreign goods. LM shifts to the right. IS shifts to the right and IS* shifts to the left by larger magnitudes than under a cooperative agreement. The foreign country must implement a large decrease in money supply, shifting LM* to the left to maintain interest rate parity. The foreign country suffers a larger decrease in Y*the home country essentially exports its recession to the foreign country. We can use the same logic to analyze the effects of a home-country revaluation. Suppose the home countrys economy is overheating with Y higher than the desired level. The analysis can be expanded to consider a center countrys choice to devalue or revalue.

328 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

Caveats

A noncooperative adjustment in the exchange rate peg (especially a devaluation) is known as a beggar-thy-neighbor policy. The home country improves its output at the expense of the foreign countrys output. This highlights a key problem with noncooperative agreements: they can lead to retaliation in which the peg is constantly adjusted, eliminating the potential gains from a xed exchange rate regime. Successful exchange rate systems involve some degree of cooperation.

APPLICATION

The Gold Standard

Is it possible to avoid the problem of asymmetric shocks in an exchange rate system? This would require that all countries are noncenter, avoiding the Nth currency problem, so that one country is unable to dominate the others with autonomous monetary policy. The gold standard is an example of such a system. Because all countries pegged to gold, no single country could act as a center country with its own currency. Mechanics of the gold standard: Britain (home) and France (foreign): Gold and money are seamlessly interchangeable. The money supply, M, equals the combined value of gold and money in the hands of the public. (Under the pure gold standard, the only acceptable money was gold coins. ). Each countrys currency is pegged to a gold local currency price: Pg, P*. Thus one pound costs 1/Pg ounces of gold and one ounce of gold g costs P* francs. In other words, an ounce of gold costs Pg pounds in g Britain and P* frances in France g The par exchange rate (British pounds per French franc): Epar Pg/P* g The gold standard depends heavily on maintaining free convertibility: central banks must be willing and able to buy or sell gold in exchange for their domestic currency. The prices are Pg, P* . g Arbitrage keeps exchange rates xed. Consider what happens when the French franc appreciates against the British pound: If E Epar, then Epar/E P* /EPg < 1. This means that an ounce of g gold costs fewer pounds in Britain (Pg) than it does in France (EP* ). g Buy one ounce of gold in Britain for (Pg) pounds Sell gold in France for P* francs g Convert the francs to EPg P* 1 pounds g Gold ows out of Britain and into France, expanding Frances money supply and contracting Britains money supply. These ows lead to a decrease in E (the franc depreciates and the pound appreciates) until the par exchange rate is achieved. Considerations and limitations: The arbitrage process is not without cost. If the exchange rate deviates from the par value by a very small amount, it will not be worthwhile to exploit the difference. This means there is effectively an exchange rate band within which the currency can appreciate or depreciate, roughly 1%. The arbitrage process works in reverse if the exchange rate is below its par value. Gold ows out of France and into Britain, expanding

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

329

Britains money supply and contracting Frances. These ows lead to an increase in E until the par exchange rate is achieved. Gold arbitrage implies interest rate parity across countries because the expected depreciation is zero. The approach to xed exchange rate regimes from earlier applies to the gold standard. Under the gold standard, there is no center country. All countries cooperate without explicit policy intervention. The gold standard has one major advantage: it is inherently symmetrical. All countries share in the adjustment process. And, since there is no reserve currency, no country has the privilege of an independent monetary policy. In reality, though, the gold standard did not operate smoothly.

4 International Monetary Experience

This section provides a historical overview of exchange rate systems, beginning in 1870 and continuing through the present. The following text summarizes this information in a timeline and key points. The Rise and Fall of the Gold Standard 18701918: The rst era of globalization and World War I Origins A combination of technological developments in transport and communications plus policy changes increased economic integration, increasing the benets associated with a xed exchange rate regime. A stabilization policy was politically irrelevant and price stability was the primary goal. Experience on the gold standard A few countries adopted a gold peg, increasing the benets to others adopting a xed exchange rate regime thereafter (network externality). Many countries joined the gold standard only to leave during a domestic economic crisis. U. S. 1890 deation and recessionWilliam Jennings Bryan cross of gold. Gold Standard Act of 1900economic growth and gold discovery meant higher output and prices. Collapse and World War I During World War I, the ination tax became an important source of revenue, leading to several countries leaving the gold standard. Conict reduced trade. Close to 100% reduction among warring countries. 50% reduction among these countries and neutral states. 19181945: The Great Depression and World War II 1920s Protectionism and beggar-thy-neighbor policies further reduced trade. By the 1930s, world trade was half of the 1914 levels.

330 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

The Great Depression (1930s) More severe output uctuations caused stabilization policies to be increasingly popular. Remaining on gold standard meant continued deation because of slow growth in the worlds gold supply. Developing countries experienced recession earlier; some devalued as early as 1929 and increasingly relied on major currencies because gold reserves were not available. Weakened condence and credibility of gold pegs indicated by currency traders. In 1931, Austria and Germany imposed capital controls. The major currencies abandon the gold standard: Britain in 1931, the United States in 1933. The trilemma revisited (Figure 15-13) Option 1: remain on the gold standard and forgo monetary policy autonomy (France). Option 2: remain on the gold standard and impose capital controls (Austria, Germany, several countries in South America). Option 3: abandon the gold standard (Britain and the United States). In the end, the system collapsed because: the efciency gains from trade were diminished as the results of war and poor macroeconomic policy stability costs became more important lack of cooperation among countries in that they did not commit to maintaining the gold peg slow growth in the worlds gold supply led to a worldwide deation Bretton Woods to the Present Background and design In 1944, economic policy makers gathered at Bretton Woods, NH to establish a cooperative international monetary system. Their objective was to maintain a system of xed exchange rates to rebuild trade among countries. All countries that signed the Bretton Woods agreement pegged their currencies to the U. S. dollar. The dollar, in turn, was pegged to gold. The Bretton Woods agreement included capital controls. Since speculators were blamed for destabilizing the gold standard, controlling the movements of capital was believed to reduce speculation. Bretton Woods performance and collapse Market pressures and the trilemma: To trade, some system of international credit was needed. Countries wanted to liberalize nancial transactions but limit speculation. By the 1960s, controls were leaky, with businesses using accounting tricks to move currency across countries or using unregulated offshore accounts.

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

331

From the trilemma, the deterioration of capital controls meant a loss of monetary policy autonomy to remain part of the Bretton Woods system. Countries compromised on a xed but adjustable system in which countries devalued as a means of stabilizing output. This made the system unstable, creating beggar-thy-neighbor policies that encouraged speculation. In the 1960s, the United States experienced ination as the result of scal expansion during the Vietnam War era. Countries pegged to the dollar would be forced to follow by expanding their money supplies, increasing ination abroad. Gradually, countries abandoned the dollar peg. In 1971, the U. S. dollar was no longer convertible to gold. Aftermath and options Countries faced several options after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system: Most advanced countries have moved to a oating exchange rate regime, preferring monetary policy autonomy over xed exchange rates. A group of European countries attempted to preserve xed exchange rates through the ERM. Today a subset of those countries is irrevocably committed to the euro. This group of countries is at the top corner of the trilemma diagram. Some developing countries have maintained capital controls, but most have opened capital markets. There is a fear of oating (benets greater than costs) for these countries. Some countries have adopted intermediate regimes, dirty oats, or pegs with limited exibility (India). A small number of countries still rely on capital controls today (China), but this is changing. Today, there is no real international monetary system in the sense of cooperative systems between countries. There are some notable exceptions, such as the establishment of the ERM and the Eurozone.

5 Conclusions

This chapter considered the choice of whether to adopt a xed or a oating exchange rate regime. The primary factors are economic integration and stability costs, with other factors such as scal discipline and liability dollarization playing an important role in emerging markets and developing countries. We considered the mechanics of a xed exchange rate regime with cooperation and noncooperation in terms of interest rate parity and exchange rate adjustments. The chapter concluded with a summary of exchange rate systems in practice, focusing on the gold standard and the Bretton Woods systems.

332 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

Teaching Tips

1. Teaching Tip 1: Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas) advocates returning the United States to the gold standard, eliminating the Federal Reserve, and allowing privately issued currency to compete with the dollar (http://www. ronpaul. com/2010-01-26/ron-paul-legalize-competingcurrencies/ and http://www. ronpaul. com/2009-02-01/going-back-tothe-gold-standard/ for example). Ask your students whether a return to the gold standard would be a good idea. Point out that most of the rest of the world would probably not follow our lead on this issue. Then ask them whether privately issued currencies are allowed in the United States. Give them a few days to do some research. You, luckily, have this resource. The E. F. Schumacher Society (Small Is Beautiful, Blond & Briggs, 1973) maintains a list of current and retired local currency experiments at http://www. smallisbeautiful. org/local_currencies/retired_in-planning. htm. So there is competition for the dollar. Have the class discuss why the dollar has maintained its monopoly position as U. S. currency in the face of this competition. 2. Teaching Tip 2: German reunication was one of the biggest news stories of 1990. Twenty years later, the shockwaves continue. As we saw in this chapter, reunication imposed large scal costs on the West German government, ultimately resulting in the United Kingdoms decision to leave the ERM. As of July, 2010, unemployment in eastern Germany was 11. 5%, almost double the 6. 5% rate in the west. And government subsidies of 80 billion owed into the east, half of which paid for social benets and welfare. The roots of this lay in the exchange rate between the West German Deutschmark (DM) and the East German ostmark (OM). Before reunication, the ofcial exchange rate was 1 to 1. But the black market rate was between ve and ten OM/DM. But, for political reasons, the West German government agreed to an exchange rate between 1 and 3 OM/DM, with prices and wages converted at a 1:1 ratio. The problem was that East German productivity was less than half that of West German workers. In effect, East German labor was priced out of the market, resulting in the large ow of subsidies that continues today. West Germany nanced the increased government spending with debt, pushing up interest rates. The rest of the story is told in the textbook. So heres the question for your students: what, if anything, should the West German government have done differently? 3. Sources: http://www. dw-world. de/dw/article/0,,6025610,00. html and http://www. sjsu. edu/faculty/watkins/germancurrency. htm

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

333

IN-CLASS PROBLEMS

1. Examine the empirical evidence on the benets and costs of currency pegs. First, identify the potential costs and benets, then evaluate each based on the empirical analysis presented in the chapter. Answer: The potential benets of a xed exchange rate regime are: efciency gains from the reduction of transactions costs and convergence in prices, scal discipline in the form of lower ination tax (seigniorage), and reduction in losses from valuation effects arising from currency mismatch in external wealth. The costs of a xed exchange rate rest mainly on lack of policy autonomy, which could otherwise be used to stabilize output. The empirical evidence is summarized as follows:

Benets Countries with a common currency and direct exchange rate peg have a higher volume of trade relative to those with oating exchange rates. There is no signicant benet for countries with indirect pegs. Evidence testing in both baskets of goods (PPP) and individual goods indicate price convergence is faster among countries with lower exchange rate volatility. Fixed exchange rate regimes do not prevent ination in general. However,

the adoption of a xed exchange rate regime does eventually reduce ination in emerging markets and developing countries. Losses in external wealth associated with valuation effects (from depreciation) can be quite large, although they depend on the percent depreciation in the currency. Countries with a larger fraction of liabilities denominated in another currency such as dollars or yen or those experiencing larger depreciations suffered larger losses in wealth. The empirical evidence indicates these losses have a signicant effect on output. Costs Interest rate movements in home countries relative to a base country. The estimated slope of the line should be equal to 1 in case 1. The data support this observation. Output volatility is higher for countries with a xed exchange rate regime relative to oat. The data show the instability is higher for poorer countries. This suggests that loss of monetary policy autonomy is costly in terms of output stability.

334 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

2.

The Bulgarian lev is currently pegged to the euro. Using the IS/LM diagrams for home (Bulgarian lev) and foreign (Eurozone) illustrate how each of the following scenarios affects the Bulgarian lev. Assume that this xed exchange rate regime involves noncooperative adjustments to interest rates and that the Eurozone is the center country. a. Bulgaria increases government spending to nance social welfare programs.

Answer: The increase in government spending leads to a rightward shift in the IS curve. This leads to an increase in home countrys interest rate and an implied appreciation in the home currency, shifting IS* to the left. In a xed exchange rate regime, the home countrys central bank shifts LM to the right to offset the increase in the home interest rate and IS* does not shift. Floating (B): Y , i , E Fixed (C): Y ; i and E unchanged

LM1 LM2

i*

LM*1

i2 i1 A

B C

i*1 i*2 IS2

IS1

IS*1 IS*2 Y Y*2 Y*1 Y*

Y1

Y2

Y3

b. The Eurozone countries decrease the money supply. Answer: The decrease in foreign money supply leads to a leftward shift in the LM* curve. This leads to an increase in foreign countrys interest rate, i*, and an implied appreciation in the foreign currency, shifting IS to the right. In a xed exchange rate

LM2 i C i3 i2 i1 B A i*3 i*2 i*1 i* LM1

regime, the home countrys central bank shifts LM to the left to align home interest rate i with the foreign interest rate i*, shifting IS* to the right. Floating (B): Y , i , E Fixed (C): Y , i , E unchanged

LM*2 LM*1 C B

IS2 IS1

IS*2 IS*1

Y3 Y1 Y2

Y*2 Y*3 Y*1

Y*

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

335

c. Investors expect a depreciation in the Bulgarian lev relative to the euro. Answer: This increases the return on foreign deposits, leading to a depreciation in the home currency, shifting IS to the right. The result is an increase in home interest rates, which shifts IS* to the left. In a xed exchange rate regime, the home countrys

central bank shifts LM to the left to prevent the depreciation and the home interest rate, i, rises, shifting IS* further to the right. Note that the interest rates may not be equal as long as investors expect a depreciation, i i*. Floating (B): Y , i , E Fixed (C): Y , i , E unchanged

LM2 i C i3 B i2 i1 A i*1 i*2 IS2 IS1 IS*2 Y3 Y1 Y2 Y Y*2 Y*1 Y*3 IS*1 Y* B IS*3 i*3 A C LM1 i* LM*1

3.

The Chinese government manages the value of the Chinese yuan relative to the U. S. dollar. Between 1995 and 2005, the yuan was pegged to the dollar at a rate of roughly 8. 28 yuan per dollar. Chinas central bank, the Peoples Bank of China (PBC), is responsible for using monetary policy to defend the xed exchange rate. As a result of government policy geared toward spurring capital investment, China experienced a signicant increase in investment demand.

a. Using the IS/LM diagram for home (China) and foreign (the United States) illustrate the impact of this policy, assuming the PBC responds to maintain a xed exchange rate. Answer: See the following diagram.

LM1 LM2

i*

LM*1

i3 i1 A

C B i*3 i*1 A B

IS2 IS*3 IS1 Y1 Y3 Y2 Y Y*1 Y*3 IS*1 Y*

336 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

b. How would this policy and central bank response affect the government budget, current account, domestic interest rates, and output? Answer: The government budget, trade balance, and home interest rate are unaffected by this policy. Chinas output increases. c. How would Chinas experience be different if the PBC allowed the yuan to oat against the U. S. dollar? What would be the implications for Chinas exports to the United States? For Chinas imports from the United States? Answer: If the yuan oats against the dollar, the increase in investment demand will lead to an appreciation in the yuan by increasing the domestic return on Chinas deposits. Chinas output increases by a smaller amount and its trade balance decreases because of the increase in Chinas interest rate and the appreciation in the yuan. This would cause a decrease in Chinas exports and an increase in Chinas imports from the United States, as shown by the rightward shift in IS* in the previous gure. d. In practice, China uses capital controls to x its exchange rate. How does this affect the previous answers? In the case of capital controls, is the outcome more similar to the xed case in (a) or the oating case in (c)?

Answer: In the case of capital controls, China can allow the interest rate in China to deviate from the U. S. interest rate through eliminating capital market arbitrage. This will result in a situation similar to the oating case mentioned previously; because interest rates need not be equal, Chinas central bank does not need to expand the money supply to prevent the appreciation in the yuan. 4. During the mid-1990s, Mexico maintained an exchange rate peg against the U. S. dollar. When President Zedillo took ofce in December 1994, he faced several challenges. A combination of the assassination of a presidential candidate (Luis Donald Colosio) and the rebellion in Chiapas had led to an increase in the expected future exchange rate, Eepeso/$. a. Using the IS/LM diagram for home (Mexico) and foreign (the United States) illustrate the impact of this change in investor expectations, assuming the Banco de Mexico responds to maintain a xed exchange rate. Answer: See the following diagram. Point B shows the oating exchange rate outcome (for comparison); point C shows the xed exchange rate output.

LM2 i i3 i2 i1 C i*3 i*1 i*2 IS2 IS*1 IS*2 Y3 Y1 Y2 Y Y*2 Y*1 Y*3 Y* A B IS*3 C LM1 i* LM*1

B A

IS1

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

337

b. How would the change in exchange rate expectations and the subsequent central bank response affect the government budget, trade balance, domestic interest rates, and output? Answer: Mexicos central bank is forced to cut the money supply to prevent an actual depreciation in the peso because investors shift deposits out of Mexico, expecting a higher return on U. S. deposits. Also, the expected depreciation leads to a rightward shift in IS because the demand for Mexicos goods rises. The increase in Mexicos interest rate leads to an increase in demand for U. S. goods, shifting IS* to the right and offsetting gains in Mexicos trade balance. c. When president-elect Ernesto Zedillo took ofce, he was forced to make a decision between either establishing an exchange rate band (effectively oating the peso against the dollar) or continuing the monetary policy mentioned previously. President Zedillo decided to establish an exchange rate band. The former President Salinas referred to Zedillos policies as el error de diciembre, or the December mistake. Do you believe this decision was a mistake? Explain, considering the trade-offs between output stabilization and exchange rate stability. Answer: Based on the previous diagram, we can see why President Zedillo may have opted to oat the peso against the dollar. In this case, Mexico does not suffer a contraction in output and its trade balance improves. This highlights the trade-off be-

tween exchange rate stability and output stability. In the case of a xed exchange rate, Mexico suffers a contraction in output. In the oating case, it experiences an expansion. d. Suppose that a large share of Mexicos external debt is denominated in U. S. dollars. How does this affect your answer to (c)? Answer: If a large share of Mexicos external debt is denominated in U. S. dollars, then a depreciation in the peso could have added costs in terms of valuation effects. The depreciation in the peso would reduce Mexicos external wealth, potentially contracting demand through reducing consumption and/or investment demand. In this case, it might be more benecial to maintain the exchange rate peg. 5. Consider a noncenter home country that is part of a xed exchange rate regime. The home country currently has output higher than its desired level. Concerned about inationary pressures, central bankers want to contract the money supply. Using the IS/LM diagrams for a home and a foreign country, show how each of the following would affect home and foreign output. In which cases are the monetary policy objectives inconsistent with the home country remaining in the xed exchange rate regime? a. The foreign country is a center country. Compare a cooperative versus a noncooperative adjustment in interest rates. Answer: See the following diagram. In the noncooperative case, there is little the home country can do. It remains at point A, un-

338 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

able to use monetary policy to achieve output stability. In the case of a cooperative agreement, the foreign country and the home country agree to raise interest rates, reducing output in both countries. This pushes output below its desired level in the foreign country and brings home country

output closer to its desired level. This cooperative agreement is similar to how autonomous monetary policy would respond, except the home country must compromise and not contract the money supply as much as what is needed to achieve desired output (otherwise the foreign country might not

LM*2 LM2 i i2 B LM1 i* i*2 B LM*1

i1

A i*1 IS2 IS1 IS*2 IS*1 Y0 Y2 Y1 Y Y*2 Y*0 Y* A

agree to raise interest rate, i*). b. The foreign country is a noncenter country. Compare a cooperative versus a noncooperative adjustment in exchange rates. Answer: See the following diagram. In this case, the home country wants to implement a currency revaluation to reduce the trade balance and contract output. In the cooperative case, the foreign country agrees to

the revaluation, compromising to let its output rise above the desired level by a small amount. In the noncooperative case, the home country revalues by a larger amount, leading to a bigger boom in output in the foreign country. Essentially, the home country exports its economic boom to the foreign country in part (in a cooperative agreement) or in full (noncooperative).

LM3

i* LM2 LM1 i*2

LM*1

LM*2 LM*3

C i1

A i*1

IS1 IS2 IS3 IS*2 IS*1 Y Y*0 Y*2 Y*3 Y*

IS*3

Y0

Y2

Y1

Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

339

6.

During the 1980s, several Latin American countries had currencies pegged to the U. S. dollar. Consider three such countries: Belize, Bolivia, and Mexico. A larger share of Mexicos exports was/is sold in the United States relative to Belizean and Bolivian exports to the United States. In addition, Mexico shares a large geographic border with the United States, whereas Belize is located further south in Central America, with coastal access to the United States through the Caribbean Sea. Bolivia is located in South America and is landlocked. Compare and contrast these three countries in terms of their likely degree of integration symmetry with the United States. Plot Belize, Bolivia, and Mexico on the symmetry-integration diagram relative to the United States. Answer: See the following diagram. Although it is not possible to determine the position of the FIX line without more information, we know that Mexico is in the upper right and Bolivia is in the lower left. Sharing a geographic border with the United States and trading heavily means Mexicos efciency gains are larger than those in Bolivia and Belize. Because Belize has coastal access to the United States and is located closer than Bolivia, it lies above and to the right of Bolivia, but below and to the left of Mexico.

7.

Several countries that have experienced political and economic stability adopt a xed exchange rate regime to draw on the potential benets, such as scal discipline, seigniorage, and expected future ination. To what extent do you believe these potential benets differ in cooperative versus noncooperative xed exchange rate systems? Answer: Cooperative exchange rate systems are generally more successful than noncooperative regimes. Countries can compromise on adjusting interest rates or exchange rates, preventing countries from being forced off of a xed exchange rate regime. With cooperation, the costs of asymmetric shocks are shared by members of the xed exchange rate regime, reducing stability costs. In practice, however, cooperative arrangements often break down because it is difcult for a country to let another countrys economic conditions dictate those at home, especially if the home country happens to be a center country. In terms of the benets, to the extent that cooperative arrangements last longer, the efciency gains from trade are higher because these take some time for the economy to realize. Also, cooperative arrangements may help impose scal discipline by providing a nominal anchor that is generally agreed upon.

8.

Symmetry of shocks

Mexico Belize Bolivia FIX Market integration

In the context of the trilemma, compare and contrast the dissolution of the gold standard during the 1920s and 1930s to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system during the 1960s and early 1970s. In what sense did the Bretton Woods system attempt to address the problems associated with the gold standard? To what extent did the Bretton Woods system strengthen or weaken a countrys ability to maintain a xed exchange rate? Answer: The gold standard collapsed for a combination of reasons:

the efciency gains from trade were diminished as the results of war and poor macroeconomic policy stability costs became more important to policy makers politically lack of cooperation between countries in that they did not commit to maintaining the gold peg slow growth in the world gold supply led to deation

340 Chapter 15

Fixed versus Floating: International Monetary Experience

In comparison, the Bretton Woods collapse stemmed from:

9.

market forces against capital controls (in addition to being at odds with nancial liberalization) changes in U. S. domestic monetary policy affecting world economic conditions breakdown in cooperation and frequent devaluations, leading to a loss of credibility in the system In the context of the trilemma, the gold standard eliminated monetary policy autonomy as an option because it was premised on free convertibility between gold and money, leaving speculators free to arbitrage. The Bretton Woods system addressed this through capital controls, leaving countries free to pursue domestic monetary policy. In addition, the Bretton Woods system pegged currencies to the U. S. dollar, rather than gold, so that the base currency could be adjusted as world economic conditions changed. In this sense, the Bretton Woods system could be successful as it offered some exibility through cooperation. The breakdown of the system stemmed from the U. S. expansion of its money supply in the 1960s (exporting its high ination rates worldwide) and the de facto deterioration of capital controls.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is often viewed as an international lender of last resort. When countries seek out loans from the IMF to alleviate banking and economic crises, the IMF often requires countries to maintain a xed exchange rate. Why do you suspect the IMF pressures countries with large levels of foreigndenominated debt to maintain xed exchange rates? Do you believe this is a good policy? Discuss possible alternatives. Answer: The IMF might require a xed exchange rate regime as a condition of lending to dissuade countries from defaulting on their external debt denominated in a foreign currency, such as the countrys loans from the IMF. As we have seen in this chapter, there is considerable debate about whether xed exchange rates are benecial. However, it is clear that a xed exchange rate regime does reduce the probability of default. An alternative would be to lend in the countrys local currency. Even if this requires higher interest rates, it would help to develop local capital markets through increased liquidity.

You might also like

- Economic IntegrationDocument3 pagesEconomic Integrationatta_tahirNo ratings yet

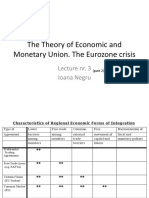

- The Theory of Economic and Monetary Union. The Eurozone CrisisDocument40 pagesThe Theory of Economic and Monetary Union. The Eurozone CrisisSalamander1212No ratings yet

- Business EconomicsDocument7 pagesBusiness EconomicsKaran ParasharNo ratings yet

- Disadvantages 1. The Instability of The SystemDocument3 pagesDisadvantages 1. The Instability of The SystemVani SvNo ratings yet

- The Mundell-Fleming Economic Model: A crucial model for understanding international economicsFrom EverandThe Mundell-Fleming Economic Model: A crucial model for understanding international economicsNo ratings yet

- European Integration and Economic Policy Coordination (2000) : Assignment 1999-2000 inDocument7 pagesEuropean Integration and Economic Policy Coordination (2000) : Assignment 1999-2000 inKonstantinos KostoulasNo ratings yet

- 2a1f7d8b61dd52f01454b9fc2ffa8fc1Document17 pages2a1f7d8b61dd52f01454b9fc2ffa8fc1Qarsam Ilyas100% (1)

- Europe'S Monetary Union The Case Against Emu The Economist, June 13, 1992Document6 pagesEurope'S Monetary Union The Case Against Emu The Economist, June 13, 1992api-63605683No ratings yet

- The ERM and The EuroDocument13 pagesThe ERM and The EuroMaria StancanNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rates Explained: Nominal Rates, Factors That Affect Currencies, Fixed vs Floating SystemsDocument6 pagesExchange Rates Explained: Nominal Rates, Factors That Affect Currencies, Fixed vs Floating SystemsRenishtaNo ratings yet

- The Potential Benefits and Costs of Adopting The Euro For United KingdomDocument4 pagesThe Potential Benefits and Costs of Adopting The Euro For United Kingdomnikunjgoyal1234No ratings yet

- Chapter - 5 Econ Policy in Open EconomyDocument14 pagesChapter - 5 Econ Policy in Open Economyabdi BediluNo ratings yet

- How Exchange Rate Regimes Impact Trade Policy Stability in Transition EconomiesDocument35 pagesHow Exchange Rate Regimes Impact Trade Policy Stability in Transition Economiesjain2007No ratings yet

- Optimal Currency Area Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesOptimal Currency Area Literature Reviewequnruwgf100% (1)

- Monetary and Fiscal Policy PDFDocument20 pagesMonetary and Fiscal Policy PDFwindows3123No ratings yet

- Measuring TradeDocument4 pagesMeasuring Trademehdi484No ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word 97 - 2003 DocumentDocument4 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word 97 - 2003 DocumentSamsar Raja KhanNo ratings yet

- How The European Monetary Union Was Created? What Are The Main Stages and Evolution of The Process?Document34 pagesHow The European Monetary Union Was Created? What Are The Main Stages and Evolution of The Process?vidya kamnurkarNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Flaws in The European Project: George Irvin, Alex IzurietaDocument3 pagesFundamental Flaws in The European Project: George Irvin, Alex IzurietaAkshay SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Exchange Rate - A-Level EconomicsDocument13 pagesThe Exchange Rate - A-Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- Fixed Exchange Rate and Floating Exchange RateDocument4 pagesFixed Exchange Rate and Floating Exchange RateDeepita Naila MuhaimenNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy, Currency Unions and Open Economy MacrodynamicsDocument50 pagesMonetary Policy, Currency Unions and Open Economy MacrodynamicsrerereNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Exchange Rate Regimes On The Stability of Trade PolicyDocument35 pagesThe Impact of Exchange Rate Regimes On The Stability of Trade PolicyNAYANNo ratings yet

- Документ Microsoft Office WordDocument2 pagesДокумент Microsoft Office WordNaila AghayevaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 (IFM)Document11 pagesLecture 1 (IFM)itxasorequejoNo ratings yet

- VJU2019 Report LeHaPhuongDocument10 pagesVJU2019 Report LeHaPhuonglhphuong03_728503220No ratings yet

- (Sesi 8) (Jurnal) - Accounting For Changing Prices - Will A Lasting Solution Be FoundDocument7 pages(Sesi 8) (Jurnal) - Accounting For Changing Prices - Will A Lasting Solution Be Foundmarrifa angelicaNo ratings yet

- I E M S C I ?: S The Uropean Onetary Ystem Onverging To NtegrationDocument33 pagesI E M S C I ?: S The Uropean Onetary Ystem Onverging To NtegrationColin BrowneNo ratings yet

- International Economics Third Mid TermDocument5 pagesInternational Economics Third Mid TermLili MártaNo ratings yet

- Britain and The Politics of The EuropeanDocument35 pagesBritain and The Politics of The EuropeanFanisNo ratings yet

- The Single European Currency: Key IssuesDocument20 pagesThe Single European Currency: Key Issuespravo20No ratings yet

- Currency Competition in The Digital AgeDocument31 pagesCurrency Competition in The Digital AgeFlaviub23No ratings yet

- International Finance Midterm TopicsDocument13 pagesInternational Finance Midterm TopicsAnisa TasnimNo ratings yet

- The European ExperienceDocument21 pagesThe European ExperienceyygorakindyyNo ratings yet

- International Economics 9Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument28 pagesInternational Economics 9Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFjocastaodettezjs8100% (9)

- Financial Crises and Reform of the International Financial SystemDocument37 pagesFinancial Crises and Reform of the International Financial SystemCamila Risso SalesNo ratings yet

- Effects of Monetory PolicyDocument5 pagesEffects of Monetory PolicyMoniya SinghNo ratings yet

- The Eurozone Crisis - Policy DilemmasDocument33 pagesThe Eurozone Crisis - Policy DilemmasRoosevelt Campus Network100% (2)

- 8868 Et 6 ETDocument15 pages8868 Et 6 ETsajad bagowNo ratings yet

- Tutor2u - Fixed and Floating Exchange RatesDocument4 pagesTutor2u - Fixed and Floating Exchange RatesSumanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Free Trade, Growth, and Convergence: Dan Ben-DavidDocument28 pagesFree Trade, Growth, and Convergence: Dan Ben-DavidMarius AdrianNo ratings yet

- AFW 3331 T1 Answers1Document7 pagesAFW 3331 T1 Answers1Zhang MengNo ratings yet

- The Standard Trade Model: Chapter OrganizationDocument8 pagesThe Standard Trade Model: Chapter OrganizationidahfNo ratings yet

- MACRO-FINANCE POLICIES IN THE EMUDocument30 pagesMACRO-FINANCE POLICIES IN THE EMUPATRICIA TRUJILLO SANZNo ratings yet

- 115 Prob Set 2 KeyDocument5 pages115 Prob Set 2 Keyyaresadaam67No ratings yet

- Workers and Unions Structural AdjustmentsDocument47 pagesWorkers and Unions Structural AdjustmentsveeerajNo ratings yet

- Working Paper Series: Cost of Borrowing Shocks and Fiscal AdjustmentDocument37 pagesWorking Paper Series: Cost of Borrowing Shocks and Fiscal AdjustmentcaitlynharveyNo ratings yet

- International Finance: Q and A 1. Illustrate and Discuss The Main Economic Benefits of A Monetary UnionDocument6 pagesInternational Finance: Q and A 1. Illustrate and Discuss The Main Economic Benefits of A Monetary UnionAlfedNo ratings yet

- Monetary and Fiscal Policy Interactions: Some Empirical Evidence in The Euro-AreaDocument23 pagesMonetary and Fiscal Policy Interactions: Some Empirical Evidence in The Euro-AreaeeeeewwwwwwwwNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy and EMU: Challenges of The Early Years: Antonio Fatás and Ilian MihovDocument23 pagesFiscal Policy and EMU: Challenges of The Early Years: Antonio Fatás and Ilian MihovPrateek JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Harry Bindloss examines trade groups and advantages/disadvantages of EMUDocument4 pagesHarry Bindloss examines trade groups and advantages/disadvantages of EMUJohn EdwardNo ratings yet

- Implic Euro For Latam Fin&Bank SysDocument47 pagesImplic Euro For Latam Fin&Bank SysKasey OwensNo ratings yet

- FINS 3616 Tutorial Questions-Week 2 - AnswersDocument5 pagesFINS 3616 Tutorial Questions-Week 2 - AnswersJethro Eros Perez100% (1)

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Single Currency 07Document3 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Single Currency 07vcs89No ratings yet

- Economic Effects of An AppreciationDocument11 pagesEconomic Effects of An AppreciationIndeevari SenanayakeNo ratings yet

- 8 International Monetary System PDFDocument22 pages8 International Monetary System PDFdevesh_mendiratta_61No ratings yet

- Economic Disturbances and Equilibrium in an Integrated Global Economy: Investment Insights and Policy AnalysisFrom EverandEconomic Disturbances and Equilibrium in an Integrated Global Economy: Investment Insights and Policy AnalysisNo ratings yet

- From Convergence to Crisis: Labor Markets and the Instability of the EuroFrom EverandFrom Convergence to Crisis: Labor Markets and the Instability of the EuroNo ratings yet

- Inflation-Conscious Investments: Avoid the most common investment pitfallsFrom EverandInflation-Conscious Investments: Avoid the most common investment pitfallsNo ratings yet