Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Measuring Construction Contractors' Organizational Learning

Uploaded by

Faisal KhalilOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Measuring Construction Contractors' Organizational Learning

Uploaded by

Faisal KhalilCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] On: 15 October 2012, At: 03:13 Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Building Research & Information

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rbri20

Measuring construction contractors' organizational learning

G.K. Kululanga , F.T. Edum-Fotwe & R. McCaffer

a a b b

Construction Management, Department of Civil Engineering, Private Bag 303 Chichiri Blantyre 3, Malawi

b

Construction Management Group, Department of Civil and Building Engineering, Loughborough University, Leicestershire, LE11 3TU, UK Version of record first published: 18 Oct 2010.

To cite this article: G.K. Kululanga, F.T. Edum-Fotwe & R. McCaffer (2001): Measuring construction contractors' organizational learning, Building Research & Information, 29:1, 21-29 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09613210150208769

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

B u i l d i n g Re s e a r c h & I n f o

r m at io n

(2001) 29(1), 2129

Measuring construction contractors organizational learning

G.K. Kululanga1 , F.T. Edum-Fotwe2 and R. McCaffer 2

1

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

Construction Management, Department of Civil Engineering, Private Bag 303 Chichiri Blantyre 3, Malawi E-mail: gkululanga@yahoo.com

2

Construction Management Group, Department of Civil and Building Engineering, Loughborough University, Leicestershire, LE11 3TU, UK E-mail: f.t.edum-fotwe@lboro.ac.uk E-mail: r.mccaffer@lboro.ac.uk

The term learning organization has entered the vocabulary of many managers and is providing an alternative basis for evaluating the performance of construction companies. However, there is a long way to go before organizational learning is fully implemented to gain competitive advantage, attain a state of readiness for change and build a capacity to respond and identify future business possibilities. This paper outlines the importance and the principles that underlie organizational learning, and presents a framework for measuring organizational learning as one of the strategies for improving construction business processes. The framework identi es ten dimensions for learning and eight factors that promote organizational generative learning. It provides a methodology for assessing whether organizational learning practices and the factors that induce organizational generative learning are in place and current best practice that characterizes learning organizations. The paper also outlines how a construction contractor can self/third-party audit its organizational learning, which could then act as a catalyst for implementing an organizational learning culture. Keywords: audit, continuous improvement, learning, management, organization Lexpression organisation intelligente fait desormais partie du vocabulaire de nombreux responsables et constitue une nouvelle base devaluation des performances des industriels de la construction. Mais on est encore loin du jour ou ` lapprentissage organisationnel sera generalise et permettra dacquerir un avantage competitif, datteindre un niveau daptitude au changement et de construire une capacite permettant de reperer les futures possibilites commerciales et dy repondre. Cette communication met laccent sur limportance et les principes sous-jacents a lapprentissage ` organisationnel et propose un cadre dans lequel mesurer cet apprentissage en tant que strategie damelioration des procedures de lindustrie de la construction. Ce cadre met en valeur dix dimensions pour lapprentissage et huit facteurs qui favorisent lapprentissage organisationnel ge ratif. Il offre une methodologie qui devrait permettre ne devaluer si les pratiques dappretissage organisationnel et les facteurs qui induisent lapprentissage organisationnel ge ratif sont en place ainsi que les meilleures pratiques actuelles qui caracterisent lorganisation intelligente. Cette ne communication rappelle egalement comment un contractant du secteur industriel de la construction peut se controler lui-meme ou controler des tiers en ce qui concerne lapprentissage organisationnel, ce qui pourrait ensuite agir comme catalyseur dans la perspective de la mise en uvre dune culture de lapprentissage organisationnel. Mots cles: audit, amelioration continue, apprentissage, gestion, organisation

Introduction

Developing a culture of organizational learning does not come by chance but is a consequence of deliberate company actions. The implicit assumption is that there is an organizational archetype that de nes a successful

culture of organizational learning and which can in uence performance, long-term effectiveness and survival of an organization. However, implementing organizational learning is complicated by the lack of a systematic approach that includes the measurement of organizational

Building Research & Information ISSN 0961-3218 print/ISSN 1466-4321 online # 2001 Taylor & Francis Ltd http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

Kululanga, Edum-Fotwe and McCaffer

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

learning capability (Goh and Richards, 1997). Although the literature on this topic has grown rapidly over the years, there is still not a systematic and measurable approach available for practical application to organizations (Garvin, 1993; Calvert et al., 1994). However, the measurement of organizational learning depends on the dimensions that contribute to organizational learning and the factors that help set the condition for double-loop learning; a process whereby organizational problems and contexts are addressed by examining the root causes and not just the readily obvious symptoms (Argyris, 1977). The challenge for construction organizations is to deliberately imbibe and create knowledge from such dimensions and support their organizational learning through factors that encourage organizational generative learning. Generative learning is a process of creative renewal and rediscovery of the purpose or reason for being for an organization in order to remain competitive (Senge, 1990). If construction contractors are to fully bene t from organizational learning principles, they must focus on how learning capabilities can be developed and how organizational learning can be measured. The main reason for developing the framework for measuring organizational learning lay in the mission to improve the competitiveness of UK construction contractors as cited by the Egan Report (1998). This paper presents an audit methodology for measuring construction contractors organizational learning as one of the drivers for meeting the challenges of the evolving business environment. It also outlines how a construction contractor can self or third-party audit its organizational learning, which could then act as a catalyst for implementing learning principles towards development of a culture for learning.

demarcation between these two views in practice is rather blurred. Therefore, organizational learning involves two processes: rst, creating or imbibing knowledge and other stimuli from the internal and external business environments and second, applying the acquired knowledge to ensure continued performance improvement. Thus, measuring learning must capture the two processes that underlie organizational learning. To ensure the required culture of learning, the cognitive and behavioural constructs that underlie organizational learning are presented. Figure 1 models various states of organizational learning that construction organizations may experience in respect of cognitive and behavioural change. Further discussion of the model is taken up later in the section on Nature of organizational learning.

Importance of organizational learning

From a doing to a thinking workforce Stata (1989) describes one of the commonly observed characteristics of learning organizations as the development of a thinking workforce from just a doing workforce. The latter merely perpetuates procedures and hardly questions the relevance of their business processes. Thus, workers perform tasks unthinkingly and fail to contribute to improvement. Such attitudes have plagued many industries including the construction industry with conservatism that has perpetuated obsolete business processes.

What is organizational learning?

Organizational learning is the systematic promotion of a learning culture within an organization such that employees at all levels, individually and collectively, continually increase their capacity to improve their level of performance. Unless the effect of organizational learning can be linked to, and made to re ect what happens when learning takes place, it can be dif cult for practising construction managers to implement the principles of organizational learning. Equally, measuring such an intangible asset is contingent upon what learning is at the organizational level (Kululanga, 1999). The literature contains a variety of de nitions for organizational learning. Each contributor to organizational learning, since Cyert and March (1963), has tried to tell a small part of what seems to be a large and complex picture. However, cognitive and behavioural views are the two most recurring constructs associated with organizational learning. The contributors to the theory development for organizational learning depict learning as a change in behaviour and cognition (Simon, 1969; Ducan and Weiss, 1979; Lundberg, 1989; Nooteboom, 1999) although the

22

From reactive to proactive readiness for change Baldwin et al. (1997) stated that the prerequisites for organizational learning to happen include situations where employees experience a common sense of direction of how their company must transform to survive now and in the future. Consequently, by developing a culture of organizational learning, construction contractors may ask what their organizations will be doing now and in the future and how they may equip themselves to cope with the ever-changing situations. To attain such capability

ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING No Cognitive Change? Yes No Yes

No

Behavioural Change?

Behavioural Change?

Yes

NO ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING FORCED ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING EXPERIMENTAL ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING

TRANSITIONAL ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING

INTEGRATED ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING BLOCKED ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING ANTICIPATORY ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING

Figure 1 Organizational learning states (after Simon, 1969; Nooteboom, 1999)

Measuring organizational learning

necessitates continuous quests for better ways of working that can assist the construction contractor to move away from being a helpless victim of uncontrollable business environment forces but an agent of change.

the challenges of the business environment. The four typical transitional organizational learning states include forced, experimental, blocked and anticipatory learning. Forced organizational learning results where any threat either internal or external in uences a change of behaviour. For example, there have been a number of instances when construction contractors have changed behaviour just to comply with government legislation. Barlow and Jashapara (1998) have argued that the use of legislation is one of the main drivers for organizational learning within the construction industry. Experimental organizational learning results whenever a company simply tries out new behaviours to address the challenges of its evolving business environment with a hope of gaining an understanding later. For example, the use of experimentation as means for continuous improvement is one of the commonly observed elements associated with total quality management. Blocked organizational learning is experienced when a construction contractor understands the type of responses it requires to make in order to address the challenges of the business environment (has experienced cognition change), but is unable to translate it into action (change its behaviour) for a number of reasons. The reasons might range from a lack of resources to translate the know-how into action to organizational defensive routines. Such routines generate resistance to change exhibited by social systems a form of dynamic conservatism or a tendency to ght to remain the same. Anticipatory organizational learning results in a business environment where companies are under the pressure of change. A typical example is the Russian business environment that initially led to resistance of rms to embrace western business values. Consequently, while a company may have high levels of cognition, it may hesitate to change its behaviour in such a business environment for fear of losing direction. Thus, a gap exists between cognitive change and the display of change in behaviour.

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

From loss to gain of competitive advantage The current pressure from knowledge era, political change, shrinking markets sweeping across the global business landscape requires companies to con gure strategies that promote competitive advantage for their survival. Thus, construction organizations must develop practices, services and products that appeal to customers through innovation. Such innovative behaviours attract clients and can ensure survival of construction organizations. It is a characteristic often associated with learning organizations (Elenkov, 1997).

From status quo to continuous improvement Continuous improvement and organizational learning are inextricably linked such that organizational learning is the most compelling reason for implementing any total quality schemes (Hill, 1996). Thus, organizational learning can offer avenues to bring about a continuous improvement agenda in construction business processes.

Nature of organizational learning

No organizational learning Construction organizations may experience no organizational learning when both their cognition and behaviour do not change. For example, people who stop learning stop living. According to Handy (1994), this is also true for organizations. Such organizations eventually go out of business (Pedler et al., 1997). Companies may fail to address the challenges of their business environment because they have no strategies within their set of experiences.

Integrated organizational learning When both cognition and behaviour change, it results in an integrated organizational learning state. In such a state, a construction contractor company acquires an awareness, which transforms its behaviour for improved performance. Such an organizational learning state results in a living company that has a readiness for change, capabilities for continuous improvement, a thinking workforce and a source of competitive advantage (de Geus, 1997).

Elements that contribute to organizational learning

In addition to the requirements of cognitive and behaviour change, organizations that are successful in meeting the challenges of the business environment are associated with driving their organizational learning from two major areas. Figure 2 presents the two conditions that need to prevail for effective organizational learning to take place. The learning dimensions de ne the different mechanisms by which learning can occur at both individual and organizational level. The effective deployment of each learning dimension is determined by the conditions under which it is applied.

23

Transitional organizational learning Transitional organizational learning occurs where a construction contractor experiences cognitive change without a corresponding change in behaviour or vice versa. In this state of transition, a company is in tension between its beliefs and the required actions for meeting

Kululanga, Edum-Fotwe and McCaffer

DIMENSIONS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO LEARNING

FACTORS THAT SET THE CONDITION FOR GENERATIVE LEARNING

ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING

Figure 2 Organizational learning archetypes

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

Basis for elements that facilitate organizational learning According to Argyris (1977), the most frequently discussed organizational learning is the distinction between styles of learning that organizations exhibit as they address their performance improvement. Table 1 presents a list of the pairings for two archetypes of learning characteristics that can be associated with organizational learning. On the one hand you have a simplistic approach to learning, and solutions to organizational problems as well as deriving options for improvement, focus exclusively on the obvious, such as pro ts. The other learning archetype, which involves double-loop or generative learning, goes beyond the obvious to explore the underlying and often remote developments that give rise to the situation under examination. These remote developments then provide a focus for fundamentally addressing the organization. Although different organization learning terms have been used for each pair the same distinction has been made. Thus, the distinction in Table 1 is useful for appreciating the variations in the terms employed for the same type of learning concept. Argyris (1977) stated that one such area involves the critical disciplines that enable organizations to address the root causes of their under performance. Without such factors organizations merely address the symptoms of their performance problems (Senge 1990). The factors that facilitate companies to address their root causes of performance problems can also be described as catalysts that promote organizational learning.

Dimensions that contribute to organization learning The organizational learning process can be separated into its constituent parts or dimensions. Such segmentation should provide a managerial instrument for measuring and monitoring organizational learning. For example, the estimating process is a well-known procedure within the construction industry as a result of isolating the parts that make up the process. Such a development has signi cantly improved the understanding of estimating process (McCaffer and Baldwin, 1991). Likewise, the segregation of the organizational learning process is aimed at facilitating the implementing of learning principles for practising construction directors in order to promote their ability to shape their organizations now and in the future. The dimensions for learning are the core areas that make up organizational learning. Each dimension has a wide variety of tools that support organizational learning as shown in Table 2. The type of tools appropriate to an individual construction contractor, for example, will vary greatly with the context and activity of that company. A fuller discussion on the how the table was generated and further guidance on its usage is provided by Kululanga (1999)

Construction companies learning pro le

A learning framework was developed through the examination of literature on organizational learning, learning organizations, knowledge management and strategic management. This led to segregating the organizational learning process into a number of sub-processes that formed the basis for the learning dimensions and the factors that set the condition for double-loop or generative learning to occur. Equally, the crucial cognitive and behavioural requirements for effective learning outcomes were examined as discussed in the preceding sections in order to provide anchored statement indicators for measuring organizational learning.

Table 1 Characteristics of the two main archetypes of organizational learning Addresses symptoms of performance problems of companies Single-loop Adaptive Operational Super cial Symptomatic Rules Lower level Tactical Addresses root causes of performance problems of companies Double-loop Generative Conceptual Substantial Systemic Insights Higher level Strategic

Learning assessment approach The assessment of a construction contractors learning capability can be established by evaluating the extent of learning processes in place, and the degree to which they are used and supported. Tables 3 and 4 present frameworks for measuring organization that encapsulates the learning dimensions and factors that facilitates generative learning. In order to provide construction contractors with a tool for facilitating their organizational learning capabilities, statement indicators linked to scores were used. Such indicators assess whether a good or a poor practice is in place. Between the two extremes of a good and a poor practice are a series of varying degrees. Thus, statements describing how learning can be achieved were employed as indicators for each of the dimensions and factors that set the condition for generative learning. The application of statements as indicators linked to scores for auditing

24

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

Table 2 Learning dimensions and mechanisms Examples of learning mechanisms as enablers Training of employees Self-learning of individuals Work groups Project teams Value analysis teams Informal and formal networking Cross functional based teams Review of failures Subcontracts Partnering Joint ventures Consortia Engineering agreements In-house research Joint research with university Joint research with construction rms Tutored by consultants Tutored by experienced practitioners Corporate mentoring Adapting the variety in the environment Continuously changing business processes External seminars Professionally based networks Employed based networks Review of innovations Technology based networks Research and development based networks Review of successes Alliancing Acquisitions with construction rms Mergers with construction rms Acquisitions and mergers with non-construction rms Mergers with non-construction rms Communication of expertise Licence agreements with other construction rms Licence agreements with non-construction rms Ad hoc work groups (team learning) External benchmarking Inter-company based networks through value chain Allowing employees to con gure new ways of working Theme focused base networks Internationally based networks Use of shows Use of exhibitions Contacting staff from innovative rms Use of trade associations Attracting staff Socially based networks Multi-scenario planning Group-ware supported learning Internal benchmarking teams Quality circles Re-engineering teams Individual learning schemes supported by a rm e.g. learning contracts

Learning dimensions

Addressing improvement through continuous learning of employee

Addressing improvement through use of teams (team learning for improvement efforts)

Addressing improvement through internal-learning within a company through sharing of knowledge

Addressing improvement from lessons from past experiences

Integrating learning with work through collaborative and non-collaborative work arrangements

Addressing improvement through investigations within the rm or by arrangement with others

Addressing improvement through learning from others

Addressing improvement through continuous renewal of business processes

Addressing improvements through seeking new developments in the business environment

Measuring organizational learning

Addressing improvement by learning about future business processes

Search conferences

25

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

26

Addressing improvement from lessons learnt from past experiences Integrating learning with work through collaborative and noncollaborative arrangements The company fully integrates learning with work. The company is fully committed to internal improvement schemes. The company is committed to key internal improvement schemes. The company is committed to learning from key partners. The company is committed to renewal of its key business processes. Renewing business processes partially exists. The company is considering learning from others. The company is considering renewing its business processes. The importance of learning from others is recognized but not acted upon. The importance of renewing business processes is recognized but not acted upon. The company is fully committed to learning from others. The company is fully committed to continuous renewal of all its business processes. The company is fully committed to search for new practices in the business environment. The company is committed to searching for key practices in the business environment. Searhcing for new practices in the business environment partially exists. The company is considering searching for new practices in the business environment. The importance of internal imporvement schemes is recognized but not acted upon. The importance of searching for new practices is recognized but not acted upon. Addressing improvement through internal improvement schemes Addressing improvement through learning from others Addressing improvement through continuous renewal of business processes Addressing improvements by seeking new developments in the business environment Addressing improvement by developing a capacity to identify and respond to future business processes The company is fully committed to learning about future business processes. The company is committed to learning about key future business processes. Learning about futures business processes partially exists. The company is considering learning about future business processes. The importance of learning about future business processes is recognized but not acted upon. The company has The company has The company has The company has no interest in no interest in no interest in no interest in internal learning from renewing its searching for new improvement others. business practices in the schemes. processes. business environment. The company has no interest in learning about future business processes. The company is fully committed to learning from its successes and failures. The company integrates learning with key work arrangements. Integrating Internal Learning from learning with work improvement others partially partially exists. schemes partially exists. exists. The company is considering integrating learning with work. The importance of integrating learning with work is recognized but is not acted upon. The company is considering under taking internal improvement schemes. Learning from successes and failures partially exists. The company is considering learning from its successes and failures. The importance of learning from successes and failures is recognized but not acted upon. The company has no interest in learning from its successes and failures. The company has no interest in integrating work with learning.

Table 3 Dimensions that contribute to organization learning

Scale

Addressing improvement through continuous employee learning

Addressing improvement through the use of teams

Addressing improvement through internal sharing of knowledge

Kululanga, Edum-Fotwe and McCaffer

The company is fully committed to employee learning at all levels.

The company is fully committed to the use of teams for addressing its improvement.

The company is fully committed to internal sharing of knowledge.

Key staff of a company are involved in continuously learning.

The use of teams for addressing improvement is limited to key staff.

Internal sharing of The company is knowledge is committed to limited to key learning from its staff. key successes and failures.

Continuous employee learning partially exists.

The use of teams for addressing improvement partially exists in the company.

Sharing of knowledge in the company partially exists.

The company is considering encouraging continuous employee learning.

The company is considering the use of teams for addressing improvement.

The company is considering sharing knowledge internally.

The importance of employee learning is recognized but not acted upon.

The importance of the use of teams for addressing improvement is recognized but not acted upon.

Importance of sharing of knowledge in the company is recognized but not acted upon.

The company has The company has The company has no interest in no interest in the no interest in employee use of teams for internal sharing of learning. improvement. knowledge.

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

Table 4 Factors that support generative learning

Rewarding innovations All members of the company have a common sense of direction. The company is fully committed to understanding the interdepedencies in improving its business processes. The company is committed to understanding the interdependencies in improving its key business processes. All employees are fully aware of their full working potential from which the company can bene t. Key employees are aware of their full working potential from which the company can bene t. Building a shared vision of the company Use of systems thinking to address improvement Encouraging personal mastery Use of mental modelling All employees are encouraged to update their values for addressing improvement. Key employees are encouraged to update their values for addressing improvement. Employees are partially encouraged to update their values for addressing improvement. Understanding interdependencies of the business processes is under consideration in the company. The importance of understanding interdependencies of the business processes is recognized but not acted upon. The company is considering promoting awareness of full working potential. The company is considering encouraging employees to update their values for addressing improvement. The importance of awareness of full working potential of employees is recognized but not realized. The importance of encouraging employees to examine and update their values is recognized but not acted upon.

Scale

Measuring business Climate of openness Committed processes leadership in learning

Qualitative or quantitative feedback on the progress of learning on business processes exists in all areas. The leadership or top Selected innovations management is are celebrated and committed to learning rewarded. with personal involvement. The company is partially committed to building a common sense of direction. Key staff have a common sense of direction.

A climate of openness The leadership or top All innovations are exists at all levels and management is fully celebrated and to all employees in the committed to learning. rewarded. company.

Qualitative or quantitative feedback on the progress of learning on businesses processes exists in key areas.

A climate of openness exists at some levels and to key employees in the company.

Qualitative or quantitative feedback on the progress of learning on business processes partially exists. The company is considering celebrating and rewarding innovations. The company is considering having a common sense of direction.

A climate of openness The leadership or top Innovations are partially exists in the management partially celebrated company. nominates and and rewarded. supports learning initiatives.

The company is Employees are partially committed to partially aware of their understanding the full working potential. interdependencies of the business processes.

The company is considering measuring the progress of learning on its business processes. The leadership or top management is sceptical of bene ts of learning. The importance of celebrating and rewarding innovations is recognized but not acted upon.

A company is The leadership or top currently attempting to management provides create a climate of spasmodic support to opennesss. learning initiatives.

The importance of qualitative or quantitative feedback on the progress of learning on business processes is recognized but is not acted upon.

The importance of a climate of openness in a company is recognized but is not acted upon.

The importance of building a common sense of direction is recognized but not acted upon.

Measuring organizational learning

Qualitative or The company is not The leadership or top quantitative feed back interested in creating management is not on the progress of a climate of openness. interested in learning. learning on business processes does not exist.

The company has no The company has no The company has interest in celebrating common sense of no interest in and rewarding direction. understanding the innovations. interdependencies of its business processes.

The company has not interested in promoting awareness of full working potential.

The company has no interest in encouraging its employees to update their values for addressing improvement.

27

Kululanga, Edum-Fotwe and McCaffer

management processes are not uncommon in the business community. Chiesa et al. (1996) provides a typical example of management audit-framework for technological capabilities.

respective sizes. Of the medium and large sized construction contractors, 85% and 95% respectively, held a similar view. The results in terms of the directors responses by number of years of operation indicate that 88% of construction contractors with less than 20 years in operation (i.e. young companies) harboured the view that the learning framework was useful for measuring organizational learning. Similarly, 89% of the construction contractors that were in operation for more than 20 years but less than 40 years, (i.e. companies that were maturing (Pearn et al., 1995)) found the framework capable of measuring organizational learning. Equally, 90% of construction contractors that were older than 40 years held a similar view. The probability that the respondents could not discriminate the usefulness of the learning framework was evaluated, which is the same as the probability for saying yes by chance for n trials. If the probability is small p , 0:01 the notion that the judgement by the directors resulted by chance is rejected. The binomial probability was applied since there were two possible outcomes which were either a yes or a no. The assumption made for the response ratio was equal and it was represented by p probability saying no 0:5 and probability saying yes (1 - p) 0:5. The signi cant test was carried out using the following binomial probability formula: ( ) ( ) n n x n- x P(x) p (1 - p) Where x x n(n - 1)(n - 2)(n - 3) . . . (n - x 1) x(x - 1)(x - 2)(x - 3) . . . 3 3 2 3 1

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

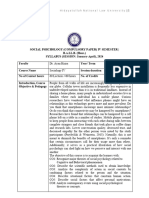

Validation of the learning framework Construction directors were directly involved in evaluating how effective the learning framework could be in measure organizational learning. The procedure involved sending the framework to two hundred large and medium construction contractors that operated in the UK. Small and micro-construction contractors were not used in the survey as they were considered to lack formalized organizational procedures, which would have created response biases. Construction contractors were drawn randomly from a database of public registered companies. Directors from 55 large and medium construction companies responded. This accounted for a response rate of 77%. The main factor that accounted for the 23% non-respondents was availability to participate during the exercise, although they had earlier approved their inclusion in the sample. This proved impractical considering the time constraint under which the exercise was conducted.

Construction directors responses Figure 3 shows the responses of construction directors by size of their companies. It can be observed that 89% of all directors perceived the framework as useful for measuring construction contractors organizational learning. The responding companies were further segregated in their

(a) 89% N5 55 11% Yes No

Large and medium construction contractors

85% N5 34 15% Yes No

Medium construction contractors (80 < number of employees < 599)

95% N5 21 5% Yes No

Large construction contractors (> 600 number of employees)

P is the probability, n was the number of trials and x is the number of yes of each category as presented in Table 5. The judgement by construction directors did not come by chance is substantiated at p , 0:01 level of the large and medium construction contractors by size and age.

Conclusions

The principles that underlie organizational learning in terms of cognitive and behaviour requirements have been articulated. The details of a framework for measuring construction contractors organizational learning capabilities were presented. The learning process of a company was separated into sub-processes with their respective factors that induce generative learning. The framework as a tool for auditing organizational learning capabilities has the potential of helping construction managers. Performance indictors such as nancial measures of a company generally rely on historical data. However, the use of the learning framework aims at promoting the application of proactive measures for intangible assets of construction contractors, which are the main drivers of business performance improvement. The usefulness of the learning framework to construction contractors was con rmed and

(b) 88% N5 Yes No

(< 20 years of operation of contractor)

89% 16 13% N5 18 11% Yes No

(20 , years of operation < 40)

90% N5 21 10% Yes No

(. 40 years of operation)

Figure 3 Usefulness of the framework by size and age of construction contractor

28

Measuring organizational learning

Table 5 Probability of chance in judgements of construction directors Chance in directors responses P (> x) 29 20 14 16 19 out out out out out of of of of of 34 21 16 18 21 or or or or or more more more more more Number of trials (n) 34 21 16 18 21 Probability P(29) P(20) P(14) P(16) P(19) P(30) . . . P(34) P(21) P(15) P(16) P(17) P(18) P(20) P(21) 1:93 3 1:05 3 2:09 3 6:56 3 1:11 3 10 10 10 10 10 5 5 3 4 4

Size or age of Medium Large < 20 years 20 < years < . 40 years

rm

40

found to be statistically signi cant by judgements of construction directors.

References

Argyris, A. (1977) Double-loop learning in organizations. Harvard Business Review, 55(5), 11525. Baldwin, T., Danielson, C. and Wiggenhorn, W. (1997) The evolution of learning strategies in organizations: from employee development to business rede nition. The Academy of Management Executives, 11(4), 4758. Barlow, J. and Jashapara, A. (1998) Organizational learning and inter- rm partnering in UK construction industry. The Learning Organization Journal, 5(2), 8698. Calvert, G., Mobley, S. and Marshall, L. (1994) Grasping the learning organization. Training and Development, 48(6), 3943. Chiesa, V., Coughlan, P. and Voss, C. (1996) Development of a technical innovation audit. Product Innovation Management, 13(2), 10536. Cyert, R.M., and March, J.G. (1963) A Behavioural Theory of The Firm, Prentice Hall, New Jersey. de Geus, A. (1997) The living company. Harvard Business Review, 70(2), 519. Ducan, R.B., and Weiss, A. (1979) Organizational learning: implications for organizational design. Research in Organizational Behaviour, 1, 75123. Egan, J. (1998) Report on Rethinking Construction, Department of the Environment Transport and Region, HMSO, London. Elenkov, D.S. (1997) Strategic uncertainty and environmental scanning, the case for institutional in uence on scanning behaviour. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4), 287302.

Garvin, D.A. (1993) Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 71(4), 7892. Goh, S. and Richards, G. (1997) Benchmarking the learning capability of organisations. European Management Journal, 15(5), 57583. Handy, C.B. (1994) The Empty Raincoat: Making Sense of the Future, Hutchinson, London. Hill, F.M. (1996) Organizational learning for total quality management through quality circles. The Total Quality Management Magazine, 8(6), 537. Kululanga, G.K. (1999) A framework to facilitate learning of construction contractors, unpublished PhD Thesis, Loughborough University, UK. Lundberg, C.C. (1989) On organizational learning: implications and opportunities for expanding organizational development, in R.W. Woodman and W.A. Pasmore (eds) Research in Organizational Change and Development, pp. 6182. McCaffer, R. and Baldwin, A.N. (1991) Estimating and Tendering for Civil Engineering Works, BSP Professional, Oxford. Nooteboom, B. (1999) Innovation, learning and industrial organization. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 23(2), 12750. Pearn, M., Roderick, C. and Mulrooney, C. (1995) Learning Organization in Practice, McGraw-Hill, London. Pedler, M., Boydell, T. and Burgoyne, J. (1997) The Learning Company: Strategy for Sustainable Development, McGraw-Hill, London. Senge, P.M. (1990) The leaders new work: building learning organizations. Sloan Management Review, 32(1), 723. Simon, H.A. (1969) Sciences of The Arti cial, MIT Press, Mass. Stata, R. (1989) Organizational learning: the key to management innovation. Sloan Management Review, Spring, 3676.

Downloaded by [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)] at 03:13 15 October 2012

29

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Version Space Concept of Machine LearningDocument48 pagesVersion Space Concept of Machine LearningFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- ANN-Advances in Forecasting With Neural Networks Empirical Evidence From The NN3 Competition On Time Series PredictionDocument26 pagesANN-Advances in Forecasting With Neural Networks Empirical Evidence From The NN3 Competition On Time Series Predictiondjtere2No ratings yet

- Python Regular Expressions Cheat Sheet PDFDocument1 pagePython Regular Expressions Cheat Sheet PDFsharathdhamodaranNo ratings yet

- Artificial Neural Networks in Bankruptcy Prediction General Framework and Cross Validation AnalysisDocument17 pagesArtificial Neural Networks in Bankruptcy Prediction General Framework and Cross Validation AnalysisFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Designing A Neural Network For Forecasting Financial and Economic Time SerieDocument22 pagesDesigning A Neural Network For Forecasting Financial and Economic Time SerieFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Management of Financial Institutions - MGT604 HandoutsDocument174 pagesManagement of Financial Institutions - MGT604 HandoutsLareb ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Applications of Artificial Neural Networks in Management Science A Survey PDFDocument19 pagesApplications of Artificial Neural Networks in Management Science A Survey PDFFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- A Hybrid ARIMA and Support Vector Machines Model in Stock Price Forecasting 2005 OmegaDocument9 pagesA Hybrid ARIMA and Support Vector Machines Model in Stock Price Forecasting 2005 OmegaFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Finance Theory: Name of Theory Page#: T P - O TDocument2 pagesFinance Theory: Name of Theory Page#: T P - O TFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Financial Management: Lecture No. 37 Dividend PayoutDocument6 pagesFinancial Management: Lecture No. 37 Dividend PayoutFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Time Value of Money - Practice ProblemsDocument5 pagesTime Value of Money - Practice ProblemsvikrammendaNo ratings yet

- Dividibility RulesDocument2 pagesDividibility RulesFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word Shortcut Keys PDFDocument7 pagesMicrosoft Word Shortcut Keys PDFIzram AliNo ratings yet

- Financial TableDocument9 pagesFinancial Tableapi-299265916No ratings yet

- Multivariate and Volatiy ModelDocument14 pagesMultivariate and Volatiy ModelFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Time Varying Model of Test of Stock ExchageDocument13 pagesTime Varying Model of Test of Stock ExchageFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- A Multivariate GARCH Model of International Transmissions of Stock Returns and VolatilityDocument27 pagesA Multivariate GARCH Model of International Transmissions of Stock Returns and VolatilityFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Prepositional & Phrasal VerbsDocument13 pagesPrepositional & Phrasal Verbsingerash_90879No ratings yet

- Egarch ModelDocument47 pagesEgarch ModelFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Volatiliry Spill Over and Contagion Asian CrisesDocument15 pagesVolatiliry Spill Over and Contagion Asian CrisesFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Stock Markets.Document6 pagesComparison of Stock Markets.Faisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Uncertainity and Stock MarketDocument17 pagesFundamental Uncertainity and Stock MarketFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Volatiliy of Stock Prices Index.Document19 pagesVolatiliy of Stock Prices Index.Faisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Volatility Comparitive StudyDocument17 pagesVolatility Comparitive StudyFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Finance Theory: Name of Theory Page#: T P - O TDocument2 pagesFinance Theory: Name of Theory Page#: T P - O TFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Forecasting Uk Stock Market.Document15 pagesForecasting Uk Stock Market.Faisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Brown - Warner - 1985 How To Calculate Market ReturnDocument29 pagesBrown - Warner - 1985 How To Calculate Market ReturnFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Garch ModelDocument92 pagesGarch ModelLavinia Ioana100% (1)

- Role of Centeral BanksDocument11 pagesRole of Centeral BanksFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Perceived Supervisory Communication Behaviors and Subordinate Organizational IdentificationDocument12 pagesThe Relationship Between Perceived Supervisory Communication Behaviors and Subordinate Organizational IdentificationFaisal KhalilNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Informative EssayDocument6 pagesInformative EssayjobNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes For Organizational Behavior Chapter 6: Perception and Individual Decision MakingDocument6 pagesLecture Notes For Organizational Behavior Chapter 6: Perception and Individual Decision MakingRicardo VilledaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Mindfulness Meditation Apps: Claudia Daudén RoquetDocument6 pagesEvaluating Mindfulness Meditation Apps: Claudia Daudén RoquetshinNo ratings yet

- Nora Bella 1298Document25 pagesNora Bella 1298Nor-zaida Kadil BalangcasiNo ratings yet

- Classification and ClusteringDocument8 pagesClassification and ClusteringDivya GNo ratings yet

- Edtech Reaction PaperDocument6 pagesEdtech Reaction PaperTine ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Main Report 3 Background StudyDocument90 pagesMain Report 3 Background StudyLi An Rill100% (1)

- MID TERM TEST - UCS3093 - QuestionDocument2 pagesMID TERM TEST - UCS3093 - QuestionSiti KhadijahNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Sylvan SyncDocument14 pagesStrategies For Sylvan Syncapi-246710812100% (1)

- Giao An Tieng Anh 6 I Learn Smart World Hoc Ki 1Document201 pagesGiao An Tieng Anh 6 I Learn Smart World Hoc Ki 1NhanNo ratings yet

- Deductive and Inductive ArgumentDocument6 pagesDeductive and Inductive ArgumentPelin ZehraNo ratings yet

- Brand Engagement SynopsisDocument15 pagesBrand Engagement SynopsisKhushboo ManchandaNo ratings yet

- Argentina and South America Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesArgentina and South America Lesson Planapi-551692577No ratings yet

- BOS 2022-23 FinalDocument175 pagesBOS 2022-23 FinalTejasri PiratlaNo ratings yet

- Smart Iep ChartDocument2 pagesSmart Iep ChartXlian Myzter YosaNo ratings yet

- K To 12 PedagogiesDocument28 pagesK To 12 PedagogiesJonna Marie IbunaNo ratings yet

- Business Essentials - Chapter 2 (Additional)Document14 pagesBusiness Essentials - Chapter 2 (Additional)Lix BammoNo ratings yet

- Chpater 1 5Document29 pagesChpater 1 5JALEAH SOLAIMANNo ratings yet

- Technology For Teaching and Learning in The Elementary GradesDocument7 pagesTechnology For Teaching and Learning in The Elementary GradesAlyssa AlegadoNo ratings yet

- Course Outline JAPA 1001Document2 pagesCourse Outline JAPA 1001AshleyNo ratings yet

- KHDA Gems Our Own Indian School 2015 2016Document25 pagesKHDA Gems Our Own Indian School 2015 2016Edarabia.comNo ratings yet

- Computer Based Examination System of TheDocument11 pagesComputer Based Examination System of ThemayetteNo ratings yet

- RyanairDocument22 pagesRyanairAdnan Yusufzai86% (14)

- Technology Has Always Flourish For The Gain of MankindDocument1 pageTechnology Has Always Flourish For The Gain of MankindJennifer BanteNo ratings yet

- Social Psychology - 4th Sem - 2024Document5 pagesSocial Psychology - 4th Sem - 2024aman.222797No ratings yet

- 5 Stages of Test ConstructionDocument8 pages5 Stages of Test ConstructionEndy HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Collection AnalysisDocument3 pagesCollection Analysisapi-329048260No ratings yet

- Thesis Vs TheoryDocument4 pagesThesis Vs Theorylniaxfikd100% (1)

- Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) Framework - Example: Indicator Baseline Target Data Source Frequency Responsible ReportingDocument2 pagesMonitoring & Evaluation (M&E) Framework - Example: Indicator Baseline Target Data Source Frequency Responsible Reportingtaiphi78No ratings yet

- Foundations of Special and Inclusive EducationDocument24 pagesFoundations of Special and Inclusive EducationStephanie Garciano94% (54)