Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transpo Digest

Uploaded by

Ian InandanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transpo Digest

Uploaded by

Ian InandanCopyright:

Available Formats

PCIC vs. UNKNOWN OWNER OF THE VESSEL M/V "NATIONAL HONOR," NSCP and ICTSI Facts: On Nov.

5, 1995, J. Trading Co. Ltd. of Korea, loaded a shipment of 4 units of parts and accessories in the port of Pusan, Korea, on board M/V "National Honor," represented in the Phils. by its agent, National Shipping Corporation of the Philippines (NSCP). The shipment was for delivery to Manila. Freight forwarder, Samhwa Inter-Trans Co., Ltd., issued Bill of Lading No. SH9410306 in the name of the shipper consigned to the order of Metrobank with arrival notice in Manila to ultimate consignee Blue Mono International Co., Inc. (BMICI). NSCP issued a Bill of Lading in the name of the freight forwarder, as shipper, consigned to the order of Stamm International Inc. The shipment, which consisted of heavy machinery, was placed in 2 wooden crates, Crate No. 1 and Crate No. 2, complete and in good order condition, and covered by a Commercial Invoice and a Packing List. There were no markings on the outer portion of the crates except the name of the consignee. On the flooring of the crates were 3 wooden battens placed side by side to support the weight of the cargo. The shipment had a total invoice value of $90,000 C&F Manila, and was insured for P2,547,270.00 with the Philippine Charter Insurance Corp. (PCIC). On Nov. 14, M/V "National Honor" arrived at the Manila International Container Terminal. The International Container Terminal Services, Inc. (ICTSI), the exclusive arrastre operator of the terminal, was furnished with a copy of the crate cargo list and bill of lading, and it knew the contents of the crate. The next day the vessel started discharging its cargoes using its winch crane. Denasto Dauz, Jr., the checker-inspector of the NSCP, along with the crew and the surveyor of ICTSI, inspected the cargo and found it in good condition. Claudio Cansino, the stevedore of the ICTSI, then placed 2 sling cables on each end of Crate No. 1. No sling cable was fastened on the mid-portion of the crate. According to Dauz, this was a normal procedure. As the crate was being hoisted, the mid-portion of the wooden flooring snapped, about 5 feet above the vessels twin deck, sending all its contents crashing down, resulting in extensive damage to the shipment. Upon receipt, BMICI found that the same could no longer be used for the intended purpose. The Mariners Adjustment Corp. hired by PCIC declared that the packing of the shipment was insufficient and opined that 3-4 pieces of cable or wire rope slings, held in all equal setting, never by-passing the center of the crate, should have been used, considering that the crate contained heavy machinery. BMICI filed separate claims against NSCP, ICTSI, PCIC, for $61,500. The other companies denied liability so PCIC paid the claim and was issued a Subrogation Receipt for P1,740,634.50. On Mar. 22, 1995, PCIC, as subrogee, filed with the RTC of Manila, a Complaint for Damages against herein defendants alleging that the loss was due their fault and negligence. ICTSI filed a Counterclaim and Cross-claim against NSCP, claiming that the loss/damage of the shipment was caused exclusively by the defective material of the wooden battens, insufficient packing or acts of the shipper. NSCP counters that if ever respondent ICTSI is adjudged liable, it is not solidarily liable with it. It avers that the "carrier cannot discharge directly to the consignee because cargo discharging is the monopoly of the arrastre."

The trial court held that the loss of the shipment was due to the internal defect and weakness of the materials used in the crates and was thus, attributable to the shipper. On appeal, the CA affirmed the trial courts decision and added that the shipper also failed to indicate an arrow in the middle portion of the cargo where additional slings should be attached. PCIC avers that the shipment was sufficiently packed in wooden boxes, as shown by the fact that it was accepted on board the vessel and arrived in Manila safely. It emphasizes that respondents did not contest the contents of the bill of lading, and that respondents knew that the manner and condition of the packing of the cargo was normal and barren of defects. It maintains that it behooved the respondent ICTSI to place three to four cables or wire slings in equal settings, including the center portion of the crate to prevent damage to the cargo. 1. Whether or not ICTSI failed to exercise extraordinary diligence in handling the shipment.

Issues: Held: No. Petition has no merit. Generally, common carriers are mandated to observe extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods and for the safety of the passengers transported by them, according to all the circumstances of each case. When the goods shipped are either lost or arrive in damaged condition, a presumption arises against the carrier of its failure to observe that diligence, and there need not be an express finding of negligence to hold it liable. As an exception, Article 1734 of the NCC provides specific cases where the presumption of negligence does not apply. Under these exceptions, the common carrier is burdened to prove any of the aforecited causes claimed by it by a preponderance of evidence in order to exculpate itself from liability. If the carrier succeeds, the burden of evidence is shifted to the shipper to prove that the carrier is negligent. Here, ICTSI was able prove that the case at bar falls under the specific exception, the character of the goods or defects in the packing or in the containers. The Court held that the issue of negligence is factual in nature and in this regard, it is settled that factual findings of the lower courts are entitled to great weight and respect on appeal, and, in fact, accorded finality when supported by substantial evidence. Trial court - the loss of the shipment was caused by the negligence of the petitioner as the shipper. The breakage and collapse of Crate No. 1 and the total destruction of its contents was due solely to the inherent defect and weakness of the materials used in the fabrication of said crate. The crate should have three solid and strong wooden batten placed side by side underneath or on the flooring of the crate to support the weight of its contents. However, in the case of the crate in dispute, although there were three wooden battens placed side by side on its flooring, the middle wooden batten, which carried substantial volume of the weight of the crates contents, had a knot hole or "bukong-bukong," which considerably affected, reduced and weakened its strength. Because of the enormous weight of the machineries inside this crate, the middle wooden batten gave way and collapsed. As the combined strength of the other two wooden battens were not sufficient to hold and carry the load, they too simultaneously with the middle wooden battens gave way and collapsed. Crate No. 1 was provided by the shipper of the machineries in Seoul, Korea. There is nothing in the record which would indicate that defendant ICTSI had any role in the choice of the materials used in fabricating this crate. CA - not only did the shipper fail to properly pack the cargo, it also failed to indicate an arrow in the middle portion of the cargo where additional slings should be attached. The petitioner failed to adduce any evidence to counter that of respondent ICTSI. The petitioner failed to rebut the testimony of Dauz, that the crates were sealed and that the contents thereof could not be seen from the outside. While it is true that the crate contained machineries and spare parts, it cannot thereby be concluded that the respondents knew or should have known that the middle wooden batten had a hole, or that it was not strong enough to bear the weight of the shipment. There is no showing in the Bill of Lading that the shipment was in good order or condition when the carrier received the cargo, or that the three wooden battens under the flooring of the cargo were not defective or insufficient or inadequate. On the other hand, under Bill of Lading issued by the respondent NSCP and accepted by the petitioner, the latter represented and warranted that the goods were properly packed,

and disclosed in writing the "condition, nature, quality or characteristic that may cause damage, injury or detriment to the goods." Absent any signs on the shipment requiring the placement of a sling cable in the mid-portion of the crate, the respondent ICTSI was not obliged to do so. The statement in the Bill of Lading, that the shipment was in apparent good condition, is sufficient to sustain a finding of absence of defects in the merchandise. Case law has it that such statement will create a prima facie presumption only as to the external condition and not to that not open to inspection. Loadstar Shipping vs. Court of Appeals 315 SCRA 339, 1999 Facts: On November 19, 1984, loadstar received on board its M/V Cherokee bales of lawanit hardwood, tilewood and Apitong Bolidenized for shipment. The goods, amounting to P6,067, 178. Were insured for the same amount with the Manila Insurance Company against various risks including Total Loss by Total Loss of the Vessel. On November 20, 1984, on its way to Manila from the port of Nasipit, Agusan Del Norte, the vessel, along with its cargo, sank off Limasawa Island. As a result of the total loss of its shipment, the consignee made a claim with loadstar which, however, ignored the same. As the insurer, MIC paid to the insured in full settlement of its claim, and the latter executed a subrogation receipt therefor. MIC thereafter filed a complaint against loadstar alleging that the sinking of the vessel was due to fault and negligence of loadstar and its employees. In its answer, Loadstar denied any liability for the loss of the shippers goods and claimed that the sinking of its vessel was due to force majeure. The court a quo rendered judgment in favor of MIC., prompting loadstar to elevate the matter to the Court of Appeals, which however, agreed with the trial court and affirmed its decision in toto. On appeal, loadstar maintained that the vessel was a private carrier because it was not issued a Certificate of Public Convenience, it did not have a regular trip or schedule nor a fixed route, and there was only one shipper, one consignee for a special crago. Issue: Whether or not M/V Cherokee was a private carrier so as to exempt it from the provisions covering Common Carrier? Held: Loadstar is a common carrier. The Court held that LOADSTAR is a common carrier. It is not necessary that the carrier be issued a certificate of public convenience, and this public character is not altered by the fact that the carriage of the goods in question was periodic, occasional, episodic or unscheduled. Further, the bare fact that the vessel was carrying a particular type of cargo for one shipper, which appears to be purely co-incidental; it is no reason enough to convert the vessel from a common to a private carrier, especially where, as in this case, it was shown that the vessel was also carrying passengers. Article 1732 also carefully avoids making any distinction between a person or enterprise offering transportation service on a regular or scheduled basis and one offering such service on an occasional, episodic or unscheduled basis. Neither does Article 1732 distinguish between a carrier offering its services to the "general public," i.e., the general community or population, and one who offers services or solicits business only from a narrow segment of the general population. LASAM VS. SMITH 45 PHIL 657 FACTS: The defendant was the owner of a public garage in the town of San Fernando, La Union, and engaged in the business of carrying passengers for hire from one point to another in the Province of La Union and the surrounding provinces. Defendant undertook to convey the plaintiffs from San Fernando to Currimao, Ilocos Norte, in a Ford automobile. On leaving San Fernando, the automobile was operated by a licensed chauffeur, but after having reached the town of San Juan, the chauffeur allowed his assistant, Bueno, to drive the car. Bueno held no drivers license, but had some experience in driving. The car functioned well until after the crossing of the Abra River in Tagudin, when, according to the testimony of the witnesses for the plaintiffs, defects developed in the steering gear so as to make accurate steering impossible, and after zigzagging for a distance of about half kilometer, the car left the road and went down a steep embankment. The automobile was overturned and the plaintiffs pinned down under it. Mr. Lasam escaped with a few

contusions and a dislocated rib, but his wife, Joaquina, received serious injuries, among which was a compound fracture of one of the bones in her left wrist. She also suffered nervous breakdown from which she has not fully recovered at the time of trial. The complaint was filed about a year and a half after and alleges that the accident was due to defects in the automobile as well as to the incompetence and negligence of the chauffeur. The trial court held, however, that the cause of action rests on the defendants breach of the contract of carriage and that, consequently, articles 1101-1107 of the Civil Code, and not article 1903, are applicable. The court further found that the breach of contact was not due to fortuitous events and that, therefore the defendant was liable in damages. ISSUE: Is the trial court correct in its findings that the breach of contract was not due to a fortuitous event? RULING: Yes. It is sufficient to reiterate that the source of the defendants legal liability is the contract of carriage; that by entering into that contract he bound himself to carry the plaintiffs safely and securely to their destination; and that having failed to do so he is liable in damages unless he shows that the failure to fulfill his obligation was due to causes mentioned in article 1105 of the Civil Code, which reads: No one shall be liable for events which could not be foreseen or which, even if foreseen, were inevitable, with the exception of the cases in which the law expressly provides otherwise and those in which the obligation itself imposes such liability. As will be seen, some extraordinary circumstances independent of the will of the obligor, or of his employees, is an essential element of a caso fortuito. In the present case, this element is lacking. It is not suggested that the accident in question was due to an act of God or to adverse road conditions which could have been foreseen. As far as the record shows, the accident was caused either by defects in the automobile or else through the negligence of its driver. That is not a caso fortuito. PRECILLANO NECESITO, ETC. vs. NATIVIDAD PARAS, ET AL. G.R. No. L-10605, June 30, 1958) FACTS: A mother and her son boarded a passenger auto-truck of the Philippine Rabbit Bus Lines. While entering a wooden bridge, its front wheels swerved to the right, the driver lost control and the truck fell into a breast-deep creek. The mother drowned and the son sustained injuries. These cases involve actions ex contractu against the owners of PRBL filed by the son and the heirs of the mother. Lower Court dismissed the actions, holding that the accident was a fortuitous event. ISSUE: Whether or not the carrier is liable for the manufacturing defect of the steering knuckle, and whether the evidence discloses that in regard thereto the carrier exercised the diligence required by law (Art. 1755, new Civil Code) HELD: Yes. While the carrier is not an insurer of the safety of the passengers, the manufacturer of the defective appliance is considered in law the agent of the carrier, and the good repute of the manufacturer will not relieve the carrier from liability. The rationale of the carriers liability is the fact that the passengers has no privity with the manufacturer of the defective equipment; hence, he has no remedy against him, while the carrier has. We find that the defect could be detected. The periodical, usual inspection of the steering knuckle did not measure up to the utmost diligence of a very cautious person as far as human care and foresight can provide and therefore the knuckles failure cannot be considered a fortuitous event that exempts the carrier from responsibility.

Batangas Transportation Company vs. Caguimbal G.R. No. L-22985 January 24, 1968 Facts: Caguimbal who was a paying pasenger of Batangas Transportation Company (BTCO) bus died when the bus of the Bian Transportation Company (Binan) which was coming from the opposite direction and a calesa managed by Makahiya, which was then ahead of the Bian bus met an accident. A passenger requested the conductor of BTCO to stop as he was going to alight, and when he heard the signal of the conductor, the driver slowed down his bus swerving it farther to the right in order to stop; at this juncture, a calesa, then driven by Makahiya was at a distance of several meters facing the BTCO bus coming from the opposite direction; that at the same time the Bian bus was about 100 meters away likewise going northward and following the direction of the calesa; that upon seeing the Bian bus the driver of the BTCO bus dimmed his light; that as the calesa and the BTCO bus were passing each other from the opposite directions, the Bian bus following the calesa swerved to its left in an attempt to pass between the BTCO bus and the calesa; that without diminishing its speed of about seventy (70) kilometers an hour, the Bian bus passed through the space between the BTCO bus and the calesa hitting first the left side of the BTCO bus with the left front corner of its body and then bumped and struck the calesa which was completely wrecked; that the driver was seriously injured and the horse was killed; that the second and all other posts supporting the top of the left side of the BTCO bus were completely smashed and half of the back wall to the left was ripped open. The BTCO bus suffered damages for the repair of its damaged portion.As a consequence of this occurrence, Caguimbal and Tolentino died, apart from others who were injured. The widow and children of Caguimbal sued to recover damages from the BTCO. The latter, in turn, filed a third-party complaint against the Bian and its driver, Ilagan. Subsequently, the Caguimbals amended their complaint, to include therein, as defendants, said Bian and Ilagan. CFI dismissed the complaint insofar as the BTCO is concerned, without prejudice to plaintiff's right to sue Bian and Ilagan. CA reversed said decision and rendered judgment for Caguimbal. BTCO appealed to SC. Issue: Whether BTCO is liable to pay damages for failure to exercise extraordinary diligence? Held: YES. BTCO has not proven the exercise of extraordinary diligence on its part. The recklessness of the driver of Binan was, manifestly, a major factor in the occurrence of the accident which resultedin the death of Pedro Caguimbal. Indeed, as driver of the Bian bus, he overtook Makahiya's horse-driven rig or calesa and passed between the same and the BTCO bus despite the fact that the space available was not big enough therefor, in view of which the Bian bus hit the left side of the BTCO bus and then the calesa. Article 1733 of the Civil Code provides the general rule that extraordinary diligence must be exercised by the driver of a bus in the vigilance for the safety of his passengers. The record shows that, in order to permit one of them to disembark, the BTCO bus driver drove partly to the right shoulder of the road and partly on the asphalted portion thereof. Yet, he could have and should have seen to it had he exercised "extraordinary diligence" that his bus was completely outside the asphalted portion of the road, and fully within the shoulder thereof, the width of which being more than sufficient to accommodate the bus. When the BTCO bus driver slowed down his BTCO bus to permit said passenger to disembark, he must have known, therefore, that the Bian bus would overtake the calesa at about the time when the latter and BTCO bus would probably be on the same line, on opposite sides of the asphalted portions of the road, and that the space between the BTCO bus and the "calesa" would not be enough to allow the Bian bus to go through. It is true that the driver of the Bian bus should have slowed down or stopped, and, hence, was reckless in not doing so; but, he had no especial obligations toward the passengers of the BTCO unlike the BTCO bus driver whose duty was to exercise "utmost" or "extraordinary" diligence for their safety. Perez was thus under obligation to avoid a situation which would be hazardous for his passengers, and, make their safety dependent upon the diligence of the Bian driver. In an action based on a contract of carriage, the court need not make an express finding of fault or negligence on the part of the carrier in order to hold it responsible to pay the damages sought for by the

passenger. By the contract of carriage, the carrier assumes the express obligation to transport the passenger to his destination safely and to observe extraordinary diligence with a due regard for all the circumstances, and any injury that might be suffered by the passenger is right away attributable to the fault or negligence of the carrier (Article 1756, new Civil Code). This is an exception to the general rule that negligence must be proved, and it is therefore incumbent upon the carrier to prove that it has exercised extraordinary diligence as prescribed in Articles 1733 and 1755 of the new Civil Code. Juntilla vs Fontanar (136 SCRA 624) Facts: Herein plaintiff was a passenger of the public utility jeepney on course from Danao City to Cebu City. The jeepney was driven by driven by defendant Berfol Camoro and registered under the franchise of Clemente Fontanar. When the jeepney reached Mandaue City, the right rear tire exploded causing the vehicle to turn turtle. In the process, the plaintiff who was sitting at the front seat was thrown out of the vehicle. Plaintiff suffered a lacerated wound on his right palm aside from the injuries he suffered on his left arm, right thigh, and on his back. Plaintiff filed a case for breach of contract with damages before the City Court of Cebu City. Defendants, in their answer, alleged that the tire blow out was beyond their control, taking into account that the tire that exploded was newly bought and was only slightly used at the time it blew up. Issue: Whether or not the tire blow-out is a fortuitous event? Held: No. In the case at bar, the cause of the unforeseen and unexpected occurrence was not independent of the human will. The accident was caused either through the negligence of the driver or because of mechanical defects in the tire. Common carriers should teach drivers not to overload their vehicles, not to exceed safe and legal speed limits, and to know the correct measures to take when a tire blows up thus insuring the safety of passengers at all tines. Vasquez vs. Court of Appeals (138 SCRA 553) Facts: MV Pioneer Cebu left the port of Manila and bounded for Cebu. Its officers were aware of the upcoming typhoon Klaring that is already building up somewhere in Mindanao. There being no typhoon signals on their route, they proceeded with their voyage. When they reached the island of Romblon, the captain decided not to seek shelter since the weather was still good. They continued their journey until the vessel reached the island of Tanguingui, while passing through the island the weather suddenly changed and heavy rains fell. Fearing that they might hit Chocolate island due to zero visibility, the captain ordered to reverse course the vessel so that they could weather out the typhoon by facing the strong winds and waves. Unfortunately, the vessel struck a reef near Malapascua Island, it sustained a leak and eventually sunk. The parents of the passengers who were lost due to that incident filed an action against Filipinas Pioneer Lines for damages. The defendant pleaded force majeure but the Trial Court ruled in favor of the plaintiff. On appeal to the Court of Appeals, it reversed the decision of the lower stating that the incident was a force majeure and absolved the defendants from liability. Issue: Whether of not Filipinas Pioneer Lines is liable for damages and presumed to be at fault for the death of its passenger? Held: The Supreme Court held the Filipinas Pioneer Lines failed to observe that extraordinary diligence required of them by law for the safety of the passengers transported by them with due regard for all necessary circumstance and unnecessarily exposed the vessel to tragic mishap. Despite knowledge of the fact that there was a typhoon, they still proceeded with their voyage relying only on the forecast that the typhoon would weaken upon crossing the island of Samar. The defense of caso fortuito is untenable. To constitute caso fortuito to exempt a person from liability it necessary that the event must be independent from human will, the occurrence must render it impossible for the debtor to fulfill his obligation in a normal manner, the obligor must be free from any participation or aggravation to the injury of the

creditor. Filipina Pioneer Lines failed to overcome that presumption o fault or negligence that arises in cases of death or injuries to passengers. Gatchalian v Delim and Court of Appeals 203 SCRA 126 Facts: Gatchalian boarded the respondents Thames minibus at San Eugenio, Aringay, La Union bound of the same province. On the way, a snapping sound was suddenly heard at one part of the bus and shortly thereafter, the vehicle bumped a cement flower pot on the side of the road, went off the road and fell into a ditch. Several passengers including the petitioner was injured. They were taken into an hospital for treatment. While there, private respondents wife Adela Delim visited and paid for the expenses, hospitalization and transportation fees. However, before she left, she had the injured passengers including the petitioner sign an already prepared Joint Affidavit constituting a waiver of any future complaint. However, notwithstanding this document, petitioner filed an action Ex Contractu to recover compensatory and Actual Damages. Private respondent denied liability on the ground that it was an accident and the Joint which constitutes as a waiver. The trial court dismissed the complaint based on the waiver and the CA affirmed. Issue: Whether or not the private respondent has successfully proved that he exercised extraordinary diligence. Held: The court held that they failed to prove extraordinary diligence. After a snapping sound was suddenly heard at one part of the bus, the driver didnt even bother to stop and look f anything had gone wrong with the bus. With regard to the waiver, it must to be valid and effective, couched in clear and unequivocal terms which leave no doubt as to the intention of the person to give up a right or benefit which legally pertains to him. In this case, such waiver is not clear and unequivocal. When petitioner signed the waiver, she was reeling from the effects of the accident and while reading the paper, she experienced dizziness but upon seeing other passengers sign the document, she too signed which bothering to read to its entirety. There appears substantial doubt whether the petitioner fully understood the joint affidavit. Trans-Asia Shipping vs. Court of Appeals (254 SCRA 260) Facts: Plaintiff (herein private respondent Atty. Renato Arroyo) bought a ticket from herein petitioner for the voyage of M/V Asia Thailand Vessel to Cagayan de Oro from Cebu City. Arroyo boarded the vessel in the evening of November 12, 1991 at around 5:30. At that instance, plaintiff noticed that some repair works were being undertaken on the evening of the vessel. The vessel departed at around 11:00 in the evening with only one engine running. After an hour of slow voyage, vessel stopped near Kawit Island and dropped its anchor threat. After an hour of stillness, some passenger demanded that they should be allowed to return to Cebu City for they were no longer willing to continue their voyage to Cagayan de Oro City. The captain acceded to their request and thus the vessel headed back to Cebu City. At Cebu City, the plaintiff together with the other passengers who requested to be brought back to Cebu City was allowed to disembark. Thereafter, the vessel proceeded to Cagayan de Oro City. Plaintiff, the next day boarded the M/V Asia Japan for its voyage to Cagayan de Oro City, likewise a vessel of the defendant. On account of this failure of defendant to transport him to the place pf destination on November 12, 1991, plaintiff filed before the trial court a complaint for damages against the defendant. Issue: Whether or not the failure of a common carrier to maintain in seaworthy condition its vessel involved in a contract of carriage a breach of its duty? Held: Undoubtedly, there was, between the petitioner and private respondent a contract of carriage. Under Article 1733 of the Civil Code, the petitioner was bound to observed extraordinary diligence in ensuring the safety of the private respondent. That meant that the petitioner was pursuant to the Article 1755 off the said Code, bound to carry the private respondent safely as far as human care and foresight

could provide, using the utmost diligence of very cautious persons, with due regard for all the circumstances. In this case, the Supreme Court is in full accord with the Court of Appeals that the petitioner failed or discharged this obligation. Before commencing the contact of voyage, the petitioner undertook some repairs on the cylinder head of one of the vessels engines. But even before it could finish these repairs it allowed the vessel to leave the port of origin on only one functioning engine, instead of two. Moreover, even the lone functioning engine was not in perfect condition at sometime after it had run its course, in conked out. Which cause the vessel to stop and remain adrift at sea, thus in order to prevent the ship from capsizing, it had to drop anchor. Plainly, the vessel was unseaworthy even before the voyage begun. For the vessel to be seaworthy, it must be adequately equipped for the voyage and manned with the sufficient number of competent officers and crew. The Failure of the common carrier to maintain in seaworthy condition its vessel involved in a contract of carriage is a clear breach of its duty prescribed in Article 1755 of the Civil Code.

You might also like

- Annex B-1 RR 11-2018 Sworn Statement of Declaration of Gross Sales and ReceiptsDocument1 pageAnnex B-1 RR 11-2018 Sworn Statement of Declaration of Gross Sales and ReceiptsEliza Corpuz Gadon89% (19)

- ManualDocument50 pagesManualspacejung50% (2)

- Study Notes - Google Project Management Professional CertificateDocument4 pagesStudy Notes - Google Project Management Professional CertificateSWAPNIL100% (1)

- Domesticity and Power in The Early Mughal WorldDocument17 pagesDomesticity and Power in The Early Mughal WorldUjjwal Gupta100% (1)

- Philippine Charter Insurance Corporation Vs ChemoilDocument2 pagesPhilippine Charter Insurance Corporation Vs ChemoilWonder WomanNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law DigestDocument36 pagesTransportation Law DigestCarlaVercelesNo ratings yet

- Transpo Case DigestDocument13 pagesTranspo Case DigestHoney GuideNo ratings yet

- Economics Exam Technique GuideDocument21 pagesEconomics Exam Technique Guidemalcewan100% (5)

- Case No. Philippine Charter Insurance Corporation, vs. NeptuneDocument2 pagesCase No. Philippine Charter Insurance Corporation, vs. Neptunem_law1No ratings yet

- Transpo Case Digests C DDocument39 pagesTranspo Case Digests C DLiene Lalu NadongaNo ratings yet

- Charter Insurance Vs MV National HonorDocument2 pagesCharter Insurance Vs MV National Honorpja_14100% (1)

- Transpo B. Common Carriers DigestsDocument24 pagesTranspo B. Common Carriers DigestsDairen RoseNo ratings yet

- Common Carriers DigestDocument9 pagesCommon Carriers DigestAaliyahNo ratings yet

- Shipping Practice - With a Consideration of the Law Relating TheretoFrom EverandShipping Practice - With a Consideration of the Law Relating TheretoNo ratings yet

- Planters Products Vs CADocument6 pagesPlanters Products Vs CAFatima Sarpina HinayNo ratings yet

- National Steel Corp Vs CA (Digested)Document2 pagesNational Steel Corp Vs CA (Digested)Lyn Lyn Azarcon-Bolo100% (4)

- 2 Phil Charter Insurance Corp Vs Unknown OwnerDocument2 pages2 Phil Charter Insurance Corp Vs Unknown OwnerMel Johannes Lancaon HortalNo ratings yet

- Loadstar Shipping vs. CADocument4 pagesLoadstar Shipping vs. CABen EncisoNo ratings yet

- Transpo Case DigestDocument10 pagesTranspo Case DigestSam FajardoNo ratings yet

- Asia Lighterage & Shipping Vs CADocument3 pagesAsia Lighterage & Shipping Vs CAShierii_ygNo ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument3 pagesReaction PaperLois DolorNo ratings yet

- Driver Drowsiness Detection System Using Raspberry PiDocument7 pagesDriver Drowsiness Detection System Using Raspberry PiIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law Digest CompilationDocument41 pagesTransportation Law Digest CompilationRafael JohnNo ratings yet

- Transpo Case DigestDocument52 pagesTranspo Case DigestJha NizNo ratings yet

- Tabacalera Insurance Co. v. North Front Shipping Services Inc.Document2 pagesTabacalera Insurance Co. v. North Front Shipping Services Inc.Mikee RañolaNo ratings yet

- Pcic vs. Unknown Owner of The Vessel M/V "National Honor," NSCP and IctsiDocument8 pagesPcic vs. Unknown Owner of The Vessel M/V "National Honor," NSCP and IctsiDaniela Erika Beredo InandanNo ratings yet

- 17 Phil Charter InsuranceDocument11 pages17 Phil Charter InsuranceMary Louise R. ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Philippine Charter Vs Unknown Owner of VesselDocument12 pagesPhilippine Charter Vs Unknown Owner of VesselZjai SimsNo ratings yet

- Phil Charter Insurance v. Unknown Owner of MV National Honor (161833)Document5 pagesPhil Charter Insurance v. Unknown Owner of MV National Honor (161833)Josef MacanasNo ratings yet

- ExtraordinaryDocument25 pagesExtraordinaryCE SherNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law DigestsDocument32 pagesTransportation Law DigestsMRose SerranoNo ratings yet

- Asia Lighterage & Shipping, Inc. Vs CA & Prudential Guarantee and Assurance, IncDocument8 pagesAsia Lighterage & Shipping, Inc. Vs CA & Prudential Guarantee and Assurance, Incerick de veraNo ratings yet

- Adalisay Transpo Cases 1st BatchDocument4 pagesAdalisay Transpo Cases 1st BatchArman DalisayNo ratings yet

- National Steel Corporation V. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 112287 December 12, 1997 Panganiban, J. DoctrineDocument23 pagesNational Steel Corporation V. Court of Appeals G.R. No. 112287 December 12, 1997 Panganiban, J. DoctrineDiane Erika Lopez ModestoNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law Case Digests-FRANCISCODocument15 pagesTransportation Law Case Digests-FRANCISCOZesyl Avigail FranciscoNo ratings yet

- CASE DIGEST (Transportation Law) : Philippine Charter Insurance Corp. vs. Unknown OwnerDocument3 pagesCASE DIGEST (Transportation Law) : Philippine Charter Insurance Corp. vs. Unknown OwnerJenniferPizarrasCadiz-CarullaNo ratings yet

- 26 Philippines Charter Insurance Corp. vs. Neptune Orient Lines Overseas Agencies Services, Inc.Document4 pages26 Philippines Charter Insurance Corp. vs. Neptune Orient Lines Overseas Agencies Services, Inc.John Rey Bantay RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Aboitiz V Insurance Company of North America GR168402Document13 pagesAboitiz V Insurance Company of North America GR168402Jesus Angelo DiosanaNo ratings yet

- Samar Mining Co., Inc. vs. Nordeutscher Lloyd (132 SCRA 529)Document4 pagesSamar Mining Co., Inc. vs. Nordeutscher Lloyd (132 SCRA 529)fe rose sindinganNo ratings yet

- Raflores 2K Transportation Law Atty. PascasioDocument19 pagesRaflores 2K Transportation Law Atty. PascasioBenjamin Agustin SicoNo ratings yet

- 128570-1993-Planters Products Inc. v. Court of AppealsDocument10 pages128570-1993-Planters Products Inc. v. Court of Appealsblude cosingNo ratings yet

- DigestDocument4 pagesDigestAlyssa Mae BasalloNo ratings yet

- Transpo (6 Jul 15)Document15 pagesTranspo (6 Jul 15)Gian CarloNo ratings yet

- Mirasol v. Dollar Bankers and Manufacturers v. CA RCL of Singapore v. TNIDocument11 pagesMirasol v. Dollar Bankers and Manufacturers v. CA RCL of Singapore v. TNIDon SumiogNo ratings yet

- Transpo - 2Document60 pagesTranspo - 2YsabelleNo ratings yet

- Transportation CASESDocument27 pagesTransportation CASESGhadahNo ratings yet

- Transpo Cases 1.1.3Document26 pagesTranspo Cases 1.1.3MaryStefanieNo ratings yet

- Planters Products Inc Vs CADocument5 pagesPlanters Products Inc Vs CARitz Esguerra BabistaNo ratings yet

- 056 - Planters Products, Inc. v. CA Case DigestDocument12 pages056 - Planters Products, Inc. v. CA Case DigestLaw StudentNo ratings yet

- Phil Charter Insurance Vs MV National Honor - G.R. No. 161833. July 8, 2005Document8 pagesPhil Charter Insurance Vs MV National Honor - G.R. No. 161833. July 8, 2005Ebbe DyNo ratings yet

- Transpo Case DigestDocument10 pagesTranspo Case DigestSam FajardoNo ratings yet

- Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. v. CA and The First Nationwide Assurance Corp. G.R. No. 97412 July 12, 1994Document4 pagesEastern Shipping Lines, Inc. v. CA and The First Nationwide Assurance Corp. G.R. No. 97412 July 12, 1994Cy PanganibanNo ratings yet

- Planters vs. CADocument8 pagesPlanters vs. CAcmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- North American Smelting Co. v. Moller S.S. Co., Inc, 204 F.2d 384, 3rd Cir. (1953)Document8 pagesNorth American Smelting Co. v. Moller S.S. Co., Inc, 204 F.2d 384, 3rd Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cokaliong Shipping Lines v. UCPBDocument2 pagesCokaliong Shipping Lines v. UCPBeieipayadNo ratings yet

- IV. Transportation A. Common Carriers: FactsDocument13 pagesIV. Transportation A. Common Carriers: FactsJohnNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 168402 August 6, 2008 Aboitiz Shipping Corporation, Petitioner, Insurance Company of North America, Respondent. Decision REYES, R.T., J.Document32 pagesG.R. No. 168402 August 6, 2008 Aboitiz Shipping Corporation, Petitioner, Insurance Company of North America, Respondent. Decision REYES, R.T., J.nina armadaNo ratings yet

- Transpo Common CarriersDocument138 pagesTranspo Common CarriersHannah Keziah Dela CernaNo ratings yet

- Planters Products Vs CA C DDocument2 pagesPlanters Products Vs CA C DKiz AndersonNo ratings yet

- Transpo Cases 11 20Document50 pagesTranspo Cases 11 20Iñigo Mathay RojasNo ratings yet

- Case 10 and 31Document2 pagesCase 10 and 31Rosalia L. Completano LptNo ratings yet

- Planters Products Vs CADocument8 pagesPlanters Products Vs CAGretch MaryNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law LLB 4302 Case Digests CompilationDocument11 pagesTransportation Law LLB 4302 Case Digests CompilationAQAANo ratings yet

- Transportation Law - DigestDocument41 pagesTransportation Law - DigestPJ SLSRNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law CasesDocument7 pagesTransportation Law CasesChicklet ArponNo ratings yet

- Transpo Module 9Document6 pagesTranspo Module 9Jerome LeañoNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Quezon City: Court of Tax AppealsDocument20 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Quezon City: Court of Tax AppealsIan InandanNo ratings yet

- QDocument2 pagesQIan InandanNo ratings yet

- KN Ewt 10.25Document2 pagesKN Ewt 10.25Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Bor RomeoDocument21 pagesBor RomeoIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Annex A RR 11-2018Document1 pageAnnex A RR 11-2018Reegan MasarateNo ratings yet

- Cta Eb CV 00652 D 2011jul12 RefDocument31 pagesCta Eb CV 00652 D 2011jul12 RefIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Court of Tax Appeals Quezon Second DivisionDocument32 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Court of Tax Appeals Quezon Second DivisionIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document19 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Handbook On Workers Statutory Monetary Benefits 2020 EditionDocument80 pagesHandbook On Workers Statutory Monetary Benefits 2020 EditionDatulna Benito Mamaluba Jr.No ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document9 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document17 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Ampatuan v. Hon. Puno, June 7, 2011Document15 pagesAmpatuan v. Hon. Puno, June 7, 2011Bianca Camille Bodoy SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document5 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Supreme CourtDocument14 pagesSupreme CourtIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document9 pagesSupreme Court: Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- En BancDocument27 pagesEn BancIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Roseller T. Lim For Petitioners. Antonio Belmonte For RespondentsDocument3 pagesRoseller T. Lim For Petitioners. Antonio Belmonte For RespondentsIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015: SearchDocument10 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015: SearchIan InandanNo ratings yet

- $ - Upreme !court: 3republic of TbeDocument9 pages$ - Upreme !court: 3republic of TbeIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document11 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015: PetitionersDocument14 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015: PetitionersIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document34 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document16 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document15 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document17 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015: PetitionersDocument14 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015: PetitionersIan InandanNo ratings yet

- Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document4 pagesToday Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Decision, Leonen (J) Separate Concurring Opinion, Carpio (J) Separate Concurring Opinion, Perlas-Bernabe (J) Dissenting Opinion, Brion (J)Document3 pagesDecision, Leonen (J) Separate Concurring Opinion, Carpio (J) Separate Concurring Opinion, Perlas-Bernabe (J) Dissenting Opinion, Brion (J)Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Document12 pagesSupreme Court: Today Is Saturday, July 25, 2015Ian InandanNo ratings yet

- 02 CT311 Site WorksDocument26 pages02 CT311 Site Worksshaweeeng 101No ratings yet

- Kootenay Lake Pennywise April 26, 2016Document48 pagesKootenay Lake Pennywise April 26, 2016Pennywise PublishingNo ratings yet

- VRARAIDocument12 pagesVRARAIraquel mallannnaoNo ratings yet

- Pyromet Examples Self StudyDocument2 pagesPyromet Examples Self StudyTessa BeeNo ratings yet

- The Intel 8086 / 8088/ 80186 / 80286 / 80386 / 80486 Jump InstructionsDocument3 pagesThe Intel 8086 / 8088/ 80186 / 80286 / 80386 / 80486 Jump InstructionsalexiouconNo ratings yet

- OsciloscopioDocument103 pagesOsciloscopioFredy Alberto Gómez AlcázarNo ratings yet

- Cln4u Task Prisons RubricsDocument2 pagesCln4u Task Prisons RubricsJordiBdMNo ratings yet

- Chemical & Ionic Equilibrium Question PaperDocument7 pagesChemical & Ionic Equilibrium Question PapermisostudyNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Raiseplus Weekly Plan For Blended LearningDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Raiseplus Weekly Plan For Blended LearningMARILYN CONSIGNANo ratings yet

- Punches and Kicks Are Tools To Kill The Ego.Document1 pagePunches and Kicks Are Tools To Kill The Ego.arunpandey1686No ratings yet

- Clinical Skills TrainingDocument12 pagesClinical Skills TrainingSri Wahyuni SahirNo ratings yet

- Written Report SampleDocument16 pagesWritten Report Sampleallanposo3No ratings yet

- Localization On ECG: Myocardial Ischemia / Injury / InfarctionDocument56 pagesLocalization On ECG: Myocardial Ischemia / Injury / InfarctionduratulfahliaNo ratings yet

- Tata NanoDocument25 pagesTata Nanop01p100% (1)

- Kiraan Supply Mesin AutomotifDocument6 pagesKiraan Supply Mesin Automotifjamali sadatNo ratings yet

- EP07 Measuring Coefficient of Viscosity of Castor OilDocument2 pagesEP07 Measuring Coefficient of Viscosity of Castor OilKw ChanNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Bearer PlantsDocument2 pagesUnit 1 Bearer PlantsEmzNo ratings yet

- Densha: Memories of A Train Ride Through Kyushu: By: Scott NesbittDocument7 pagesDensha: Memories of A Train Ride Through Kyushu: By: Scott Nesbittapi-16144421No ratings yet

- Documentos de ExportaçãoDocument17 pagesDocumentos de ExportaçãoZineNo ratings yet

- Req Equip Material Devlopment Power SectorDocument57 pagesReq Equip Material Devlopment Power Sectorayadav_196953No ratings yet

- Joomag 2020 06 12 27485398153Document2 pagesJoomag 2020 06 12 27485398153Vincent Deodath Bang'araNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Doing Business in Grenada & OECSDocument14 pagesGuidelines For Doing Business in Grenada & OECSCharcoals Caribbean GrillNo ratings yet

- Ferobide Applications Brochure English v1 22Document8 pagesFerobide Applications Brochure English v1 22Thiago FurtadoNo ratings yet

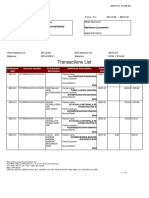

- Transactions List: Marilena Constantin RO75BRDE445SV93146784450 RON Marilena ConstantinDocument12 pagesTransactions List: Marilena Constantin RO75BRDE445SV93146784450 RON Marilena ConstantinConstantin MarilenaNo ratings yet